Published online Dec 28, 2020. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v8.i6.447

Peer-review started: November 23, 2020

First decision: December 8, 2020

Revised: December 8, 2020

Accepted: December 23, 2020

Article in press: December 23, 2020

Published online: December 28, 2020

Processing time: 35 Days and 1.8 Hours

Although panic buying (PB) is a ubiquitous behavior, it became prominent during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. However, studies are inadequate to explore the different aspects of it, even though it covers several perspectives of life and academic domains.

To assess the research that have been conducted on PB.

A search was conducted to identify the articles in PubMed, PubMed Central, Scopus, and Google Scholar using the search term “panic buying” on November 15, 2020. A total of 104 articles was extracted from the initial search. After removing duplicates and initial and full-text screening, 42 articles were included in the study. We only considered peer-reviewed published articles that can be downloaded in a full portable document format. Articles published in other languages and preprints were excluded.

Among the 42 articles, 27 were original contributions, 6 were correspondences, 3 were commentaries, 3 were review articles, and there was one each for editorial, opinion, and discussion type of articles. Several domains have been researched such as psychology, responsible factors, supply chain, management, disaster preparedness, e-commerce, consumer behavior, marketing, prevention strategies, media, social network, economics, personality, and engineering. Authors from several disciplines, such as psychiatry, management, economics, business, sales and marketing, consumer behavior, public health, communication, information management, sociology, engineering, business administration, psychology, nursing, health economics, food policy, epidemiology, and community health, have been studied it. Definition, causative model, econometric model, controlling strategy, and measuring instrument have been reported. A total of 18 papers had cross-country collaboration, and ten were funded projects. Most of the authors were affiliated with the institutions of Australia, Bangladesh, China, India, Singapore, and the United States.

PB is a relatively newer concept to get the attention of the research community. Further robust studies with replication of the findings are warranted to explore, predict, and control during crises.

Core Tip: Panic buying is an under-researched emerging research problem. Although it covers several aspects of human life, there is a dearth of studies. This review was aimed to assess the extent of research that has been done on panic buying. A total of 42 papers were included after a systematic search. Several domains have been researched such as psychology, responsible factors, supply chain, management, disaster preparedness, e-commerce, consumer behavior, marketing, prevention strategies, media, social network, economics, personality, and engineering. Definition, causative model, econometric model, controlling strategy, and measuring instrument have been reported.

- Citation: Arafat SMY, Hussain F, Kar SK, Menon V, Yuen KF. How far has panic buying been studied? World J Meta-Anal 2020; 8(6): 447-461

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v8/i6/447.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v8.i6.447

Panic buying (PB) is an interesting behavioral phenomenon, usually noticed among the public in the face of disasters. The term “panic buying” consists of two words “panic” and “buying,” which refer to the affective and behavioral components of this phenomenon. It has some common roots with stockpiling[1]. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has witnessed an increase in PB behavior globally, irrespective of the socioeconomic status of the country[2,3]. It has been conceptualized as “the phenomenon of a sudden increase in buying of one or more essential goods in excess of regular need provoked by adversity, usually a disaster or an outbreak resulting in an imbalance between supply and demand”[4]. Several intermingled factors interact with each other to influence it, pointed out as primary (provoking stimuli), secondary (media and psychosocial aspects), and tertiary (utility, demand, and price of the goods) factors[2]. Multiple psychological explanations have been proposed such as anticipation of shortage and price hike, supply disruption, fear, uncertainty, maladaptive coping, and maintaining control over the environment to attribute it[2,5-7]. There are complex interactions between media, environment, rumor, and increased demand and price as these factors can have a bidirectional role with PB[2,3,6,8]. It has been traced in response to an adverse stimulus, such as COVID-19, pandemic, war, government’s declaration, any policy change, disaster, etc.[2,9].

Theoretically, PB shares multiple aspects of human life and several domains of academia. It is related to behavior, public health, disaster preparedness, mass media, economics, sociology, business, marketing, supply chain, industrial buying and production, e-commerce, and so on[8]. However, there is a dearth of studies exploring the different aspects of it. Although studies are recently coming out, the issue is still under-researched. With this background, we aimed to conduct a review to assess the extent of research on PB that has been conducted.

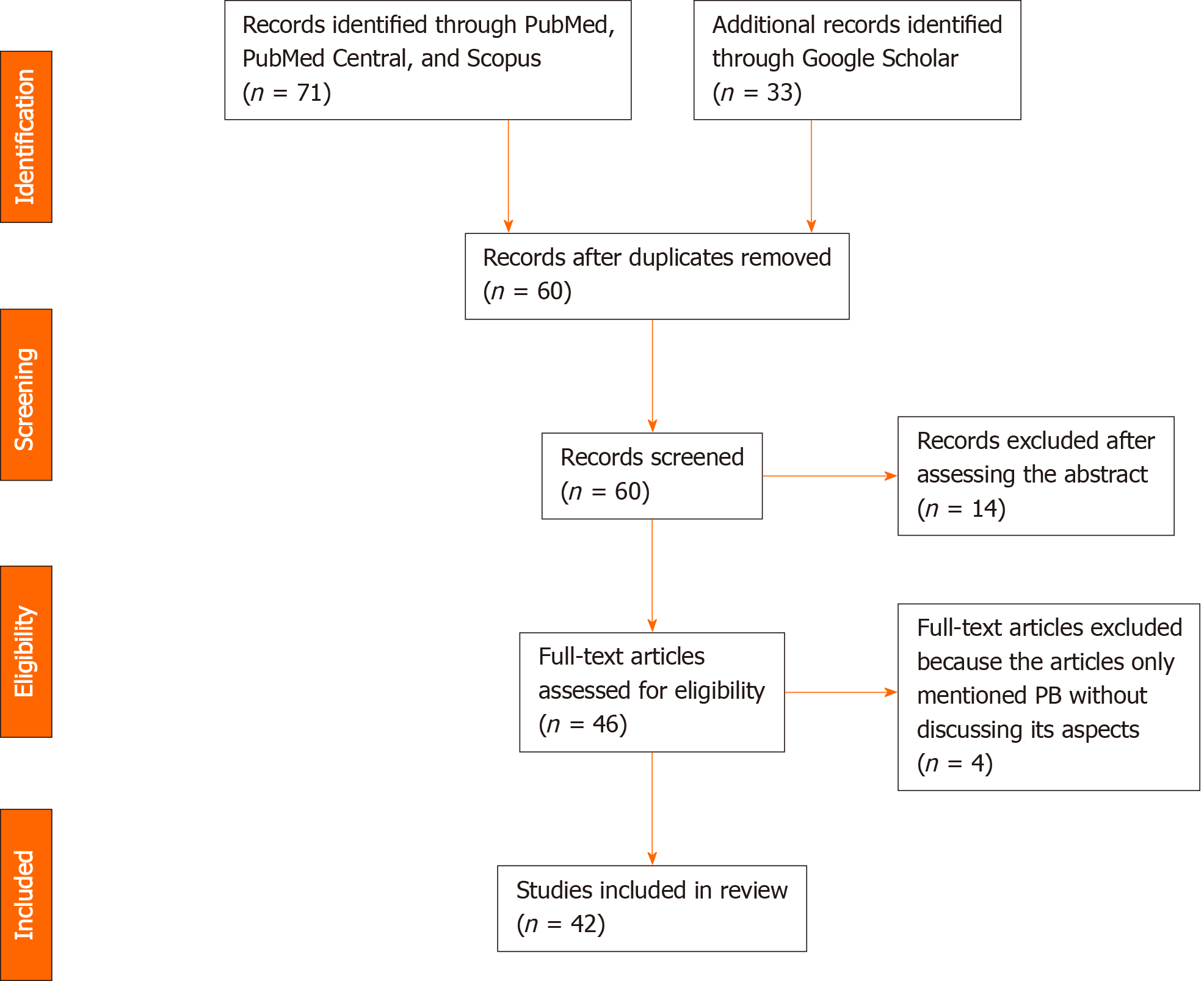

A search was done to identify the articles in PubMed, PubMed Central (PMC), Scopus, and Google Scholar (GS) with the search term “panic buying” on November 15, 2020. A total of 104 (PubMed = 19, PMC = 22, Scopus = 30, GS = 33) articles were extracted from the initial search. Subsequently, 44 duplicate articles were removed, and the remainder of the 60 articles were screened. After screening the abstract, another 14 articles were removed as PB was not identified as a study variable. Then, full texts were screened resulting in the removal of four articles because the articles only mentioned PB without discussing its aspects. Finally, 42 articles were included in the study (Figure 1).

We included peer-reviewed published articles that were extracted from the search and downloadable as full portable document format in the study.

Articles published in other languages (for example, Bangla, German, Chinese, and French) and preprints were excluded from the study.

Type of research, publishing year, applied method, key findings, the geographical distribution of the authors, specialty of authors, collaboration (intracountry or intercountry), a major subject of the journal where the articles published, a principal domain discussed in the article, funding status, and keywords were outcome variables. We considered the first authors‘ and corresponding authors’ affiliated institutions’ location to describe the authors‘ geographical locations.

In the current study, we assessed the aspects of PB research, detail statistical analysis was not performed. We did a word cloud of the keywords of the articles to reveal highlighting search terms mentioned in the articles.

The study was conducted complying with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964). As we analyzed the publicly available media reports, no formal ethical approval was sought.

In this review, we searched articles from PubMed, PMC, Scopus, and GS, and 42 articles were reviewed. The articles were published between 2002 and 2020 whilst 36 papers were published in 2020 (Table 1). Among the selected articles, 27 were original articles, 6 were correspondences, 3 were commentaries, 3 were review articles, and 1 each were editorial, opinion, and discussion type of articles (Table 1).

| No. | Ref. | Year | Type | Title | Method applied | Key message |

| 1 | Ahmed et al[10] | 2020 | Original | The COVID-19 pandemic and the antecedents for the impulse buying behavior of US citizens | Survey (online and offline) | This study sorted out nine variables from the literature that may influence impulsive buying and tested them by conducting surveys in major United States cities. The variables include fear of complete lockdown, peer buying, the limited supply of essential goods, empty shelves, United States stimulus checks, panic buying, fear appeal, social media fake news, and COVID-19. |

| 2 | Alchin[11] | 2020 | Commentary | Gone with the wind | This paper proposes a definition of “panic buying,” with references to literature, philosophy, and contemporary neurobiology. The self-fulfilling prophecy, the contagion model of emotional propagation, the Polyvagal Theory, and Nietzsche‘s study of the classical tragedy were discussed in relation to panic buying. | |

| 3 | Alfa et al[12] | 2020 | Original | Effect of panic buying on individual savings: The COVID-19 lockdown experience | Cross-sectional | The paper assessed the microeconomic effect of PB on the savings of an individual. This study’s findings revealed that price fluctuation, price differential, and spending hurt the individual saving rate. |

| 4 | Arafat et al[2] | 2020 | Original | Responsible factors of panic buying: An observation from online media reports | Analysis of media reports | The authors analyzed 784 media reports to find out the reported responsible factors of panic buying. A sense of scarcity, increased demand, importance of the product, and anticipation of the price hike were the major contributing force towards PB, as mentioned in the reports. The authors postulated a causative model of PB. |

| 5 | Arafat et al[3] | 2020 | Original | Media portrayal of panic buying: A content analysis of online news portals | Analysis of media reports | This study analyzed content published in media to determine how media is depicting PB during COVID-19.The findings suggested that the media have been portraying more negative aspects of PB. The authors recommended developing media guidelines to censor news that influences impulse buying behavior. |

| 6 | Arafat et al[4] | 2020 | Original | Panic buying: An insight from the content analysis of media reports during COVID-19 pandemic | Media report analysis | The authors proposed a definition of PB. This study analyzed information extracted from English media reports to evaluate the nature, extent, and impact of PB. |

| 7 | Arafat et al[5] | 2020 | Correspondence | Psychological underpinning of panic buying during pandemic (COVID-19) | The authors studied psychological reasons of PB, which include fear of scarcity, insecurity, losing control over the environment, social learning, and exacerbation of anxiety. | |

| 8 | Arafat et al[8] | 2020 | Correspondence | Possible controlling measures of panic buying during COVID-19 | The authors mentioned possible measures to control PB during a pandemic. The recommendations included positive role-playing by media. Promotion of feeling of kinship and encouraging generosity can reduce it from the public end. Setting a quota policy and subsidiary sales for necessity items could be a potential strategy. | |

| 9 | Arafat et al[9] | 2020 | Correspondence | Panic buying: Is it really a problem? | The paper mentioned some challenges to study PB in detail to explore its several aspects | |

| 10 | Benker[13] | 2020 | Original | Stockpiling as resilience: Defending and contextualising extra food procurement during lockdown | Online interview | This study analyzed 19 invited interviews taken online in the United Kingdom. The study found that though food shortages were common for a couple of weeks, food hoarding didn’t make impulsive buying. The United Kingdom households considered food procurement as a single resilience strategy among the taken six strategies. |

| 11 | Chen et al[14] | 2020 | Discussion | A discussion of irrational stockpiling behaviour during crisis | The authors discussed the current and long-term impact of PB on the economy, society, and local communities. They think that stopping impulse buying is impossible, but it should be controlled by improving the supply chain and maintaining communication with the stakeholders. | |

| 12 | Dammeyer[15] | 2020 | Original | An explorative study of the individual differences associated with consumer stockpiling during the early stages of the 2020 Coronavirus outbreak in Europe | Online survey | This study answered whether individual differences influenced PB during crises. The authors found a high tendency of stockpiling on extroversion and neuroticism and a relatively low tendency on conscientiousness and openness. |

| 13 | Dickins et al[16] | 2020 | Original | Food shopping under risk and uncertainty | Authors analyzed super market sales data | In this study, the authors showed the importance of food security and suggested optimality models of foraging under risk and uncertainty as foraging correlates to PB. |

| 14 | Dulam et al[17] | 2020 | Original | Development of an agent-based model for the analysis of the effect of consumer panic buying on supply chain disruption due to a disaster | Simulation model | This study used an agent-based simulation model to analyze how a supply chain responds to consumer PB caused by a natural disaster. The authors found this model useful in applying a quota policy per person to protect the supply chain from disruption. |

| 15 | Du et al[18] | 2020 | Original | COVID-19 increases online searches for emotional and health-related terms | Data mining from Google Trends | This study measured fear-related emotions, protective behaviors, seeking health-related knowledge, and PB due to COVID-19 prevalence in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia using internet search volumes in Google Trends. The results found that the increased prevalence of COVID-19 was associated with panic buying consistently in all four countries. |

| 16 | Hall et al[19] | 2020 | Original | Beyond panic buying: consumption displacement and COVID-19 | Cross-sectional | The authors analyzed consumer spending data acquired from financial third parties and found instances of PB for grocery, home, hardware, and electrical categories that happened in the Canterbury region of New Zealand before the lockdown that lasted less than a week. The study showed a high consumption displacement in the hospitality and retailing sectors that dominate this area’s economy. |

| 17 | Hao et al[20] | 2020 | Original | Impact of online grocery shopping on stockpile behavior in COVID-19 | Online survey | It investigated how online shops affect the food stockpiling manner among urban consumers in China using bivariate probit models. The authors recommended improved and resilient supply chains that can withstand intense PB phenomena during emergencies. |

| 18 | Islam et al[21] | 2020 | Original | Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination | Online survey | The authors surveyed 1081 people from United States, China, India, and Pakistan to test their conceptual model and hypotheses. The research revealed that stimuli such as Limited Quantity Scarcity and Limited Time Scarcity affect emotional stress, which eventually influences impulse buying. The findings also correlated excessive social media use to PB and discussed some managerial implications. |

| 19 | Jeżewska-Zychowicz et al[22] | 2020 | Original | Consumers’ fears regarding food availability and purchasing behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: The importance of trust and perceived stress | Cross-sectional | It investigated how the public perception of food availability changed based on the trust in the received information from media and friends. The participants showed less trust in media for COVID updates but high trust in media and friends for food availability updates and increased buying more food than usual. The consumers were highly afraid of empty shelves in the market, which also motivated them to stockpile food. |

| 20 | Kar et al[23] | 2020 | Correspondence | Online group cognitive behavioral therapy for panic buying: Understanding the usefulness in COVID-19 context | The authors postulated to explain the usefulness of online group CBT in COVID19 context for controlling the PB. | |

| 21 | Keane et al[24] | 2020 | Original | Consumer panic in the COVID-19 pandemic | Data mining using Google Health Trends API | The authors developed an econometric model of consumer panic using Google search data for 54 countries from January 1st to April 30th, 2020. Findings included limited movement notice announced by local or foreign governments generated a week-long short-run panic. The study found little impact of stimulus offerings and no consumer panic due to travel restrictions. |

| 22 | Kostev et al[25] | 2020 | Original | Panic buying, or good adherence? Increased pharmacy purchases of drugs from wholesalers in the last week before Covid-19 lockdown | Retrospective cross-sectional analysis of the IMS RPM® (Regional Pharmaceutical Market) Weekly database | The paper assessed the PB of medication during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. The study suggested that Germany’s lockdown was associated with a sharp increase in purchasing behavior in pharmacies for different markets, including psychotropic, neurological, and cardiovascular drugs. |

| 23 | Laato et al[26] | 2020 | Original | Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach | Online survey | The authors conducted a web survey with 211 Finnish participants for a week to test a hypothetical research model. The study found a positive link between voluntary self-isolation and unusual purchases. The online information overload caused cyberchondria, which eventually motivated self-isolation followed by PB. |

| 24 | Lins et al[27] | 2020 | Original | Development and initial psychometric properties of a panic buying scale during COVID-19 pandemic | Online survey | This study developed the first PB scale that was psychometrically acceptable in the Brazilian context. |

| 25 | Loxton et al[28] | 2020 | Review | Consumer behavior during crises: Preliminary research on how coronavirus has manifested consumer panic buying, herd mentality, changing discretionary spending and the role of the media in influencing behaviour | Literature review and cross-sectional data analysis | This study reviewed consumer behavior data, including impulse buying, herd instinct, and prioritization of purchasing decisions of past crises and shock events. The authors then analyzed consumer spending data acquired from data services that confirmed the sorted variables in the COVID-19 context. |

| 26 | Martin-Neuninger et al[29] | 2020 | Opinion | What does food retail research tell us about the implications of coronavirus (COVID-19) for grocery purchasing habits? | The paper discussed the consequences of lockdowns on consumer grocery purchasing habits, focusing on New Zealand. In avoidance of PB, the authors suggested few recommendations to the food companies so that people can enjoy visiting supermarkets without compromising safety. They also asked to improve online delivery services to gain trust and customer confidence. | |

| 27 | Micalizzi et al[1] | 2020 | Original | Stockpiling in the time of COVID-19 | Survey | This study aimed to discuss stockpiling behavior during COVID-19 and investigated individual predictors of stockpiling. Those affiliated with conservative politics, worry much about COVID-19, and self-isolated were prone to stockpiling behavior. |

| 28 | Naeem[30] | 2020 | Original | Do social media platforms develop consumer panic buying during the fear of Covid-19 pandemic | Telephonic interview | The study revealed how social media aggravated PB by arousing fear appeal. Along with some exacerbating factors like uncertainties, anxiety, persuasive buying, empty shelves, and exert opinion, a huge load of information at users’ fingertips made them more anxious about what was to come, leading to panic buying. |

| 29 | Prentice et al[31] | 2020 | Original | Timed intervention in COVID-19 and panic buying | Semantic analysis, secondary data and big data analysis | This paper depicted PB as a side effect of the Australian government’s timed-intervention policy. The authors supported their findings with real-life evidence. |

| 30 | Rosita[32] | 2020 | Review | Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic era in Indonesia | Literature review | This paper proposed a definition of PB and extrapolated some underlying reasons for it. It also mentioned the negative impact of impulsive buying and recommended some stakeholders’ measures to control it. |

| 31 | Shorey et al[33] | 2020 | Original | Perceptions of the public on the COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore: A qualitative content analysis | Qualitative content analysis | This study analyzed 2075 comments made to the 29 published news by local media outlets on their Facebook pages to find common concerns shared by Singapore’s public. The five main themes derived from the qualitative thematic analysis were fear and concern, PB and hoarding, reality and expectations about the situation, staying positive amid the ‘storm,’ and worries about the future. The authors recommended clear communication, timely updates, and support measures from the government to maintain social peace and cohesion. |

| 32 | Sim et al[6] | 2020 | Correspondence | The anatomy of panic buying related to the current COVID-19 pandemic | The paper mentioned two episodes of PB in Singapore due to a new alert level set by the local authority and the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic by the World Health Organization. The authors found some underlying reasons for PB and suggested some recommendations to facilitate it. | |

| 33 | Singh et al[34] | 2020 | Commentary | A critical analysis to comprehend panic buying behaviour of Mumbaikar’sin COVID-19 era | The authors studied different driving factors of PB and suggested how the retailers should adapt inventory when the supply chain is under disruption. They recommended stopping the panic buying so that others can get the share of the products. | |

| 34 | Turambi et al[35] | 2020 | Original | Panic buying perception in Waliansatu sub-district, Tomohon City | Online survey | This study analyzed the perception of city dwellers towards PB due to COVID-19. It described different PB episodes that appeared in a city in Indonesia. |

| 35 | Yuen et al[7] | 2020 | Review | The psychological causes of panic buying following a health crisis | Systematic review | It was the first systematic review on PB. The authors identified four major themes responsible for PB. |

| 36 | Zheng et al[36] | 2020 | Original | Supply disruption management under consumer panic buying and social learning effects | Analytical study | The study analyzed how social learning among customers can influence buying decisions when adequate supply is at risk. When the panic intensity is at a moderate level, social learning can help to adjust the consumer demand, but it will work negatively when the panic intensity is very low or very high. The authors also introduced an optimal inventory ordering strategy for retailers. |

| 37 | Tsao et al[37] | 2019 | Original | Product substitution in different weights and brands considering customer segmentation and panic buying behavior | Mathematical model | It proposed a mathematical model for managing wholesaler’s inventory to maximize the profit during PB. The authors suggested substituting the same products of different weights and brands between high- and low-indexed stores during a supply disruption. The model can determine optimal order quantity, the number of substitutable units, leftover units, and the unsated demand to improve the store services. |

| 38 | Wei et al[38] | 2011 | Original | Research on emergency information management based on the social network analysis — A case analysis of panic buying of salt | Data mining | This research studied how to manage information in an emergency analyzing social network to control PB. |

| 39 | Fung et al[39] | 2010 | Original | Disaster preparedness of families with young children in Hong Kong | Survey | This study surveyed households’ heads to explore their perception and preparedness for future disastrous events most likely to occur in Hong Kong. These families experienced PB for necessities during disasters especially for children’s items and drugs. |

| 40 | Kulemeka[40] | 2010 | Commentary | United States consumers and disaster: Observing "panic buying" during the winter storm and hurricane seasons | This article was an update of ongoing research. This article narrated predisaster shopping and claimed that such shoppers do not go for panic buying rather help each other. | |

| 41 | Bonneux et al[41] | 2006 | Correspondence | An iatrogenic pandemic of panic | The authors mentioned humans’ overreactions to the perceived threat of a hypothetical pandemic accompanied by clever marketing for the panic buying of antiviral drugs. | |

| 42 | Thomas[42] | 2002 | Editorial | Panic buying ahead? | The author highlighted the preparedness for future PB influenced by herd instinct in the semiconductor industry. |

Nine studies surveyed the target population online or offline, five studies applied cross-sectional data analysis, four papers studied social media, three studies analyzed media reports, and two studies mined data from Google search volume using Google Trends application programming interface (Table 1).

Definition of PB, causative model, econometric model, media reporting of PB, responsible factors for PB, psychological reasons for PB, controlling strategy, measuring instrument, challenges to explore the problem, and geographical distribution have been identified.

Several domains have been researched such as psychology, supply chain, management, disaster preparedness, e-commerce, consumer behavior, marketing, prevention strategies, media, social network, economics, personality, and engineering (Table 2).

| Ref. | Author No. | Month of publication | Country of the 1st author | Country of the corresponding author | Specialty of the | Specialty of the corresponding author | Collaboration | Journal | Subject of the journal | Domain of the discussed topic | Funding |

| Ahmed et al[10] | 4 | Aug 20 | Pakistan | Pakistan | Sales and Marketing | Sales and Marketing | Cross-country | J of Competitiveness | Competitiveness | Impulse buying behavior | No info |

| Alchin[11] | 1 | Jul 20 | Australia | Australia | Public health | Public health | Australasian Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Panic buying during disaster | No funding | |

| Alfa et al[12] | 2 | Sep 20 | Nigeria | Nigeria | Economics | Economics | Intracountry | Lapai J of Economics | Economics | Economics | No info |

| Arafat et al[2] | 7 | Nov 20 | Bangladesh | Bangladesh | Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Cross-country | Frontiers in Public Health | Public health | Media | No funding |

| Arafat et al[3] | 9 | Sep 20 | Bangladesh | Bangladesh | Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Cross-country | Global Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Media | No funding |

| Arafat et al[4] | 9 | Jul 20 | Bangladesh | Bangladesh | Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Cross-country | Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research | Psychiatry | Media | No funding |

| Arafat et al[5] | 6 | May 20 | Bangladesh | Bangladesh | Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Cross-country | Psychiatry Research | Psychiatry | Psychological causes of panic buying | No funding |

| Arafat et al[8] | 3 | May 20 | Bangladesh | Bangladesh | Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Cross-country | Int J of Mental Health and Addiction | Psychiatry | Controlling of panic buying | No funding |

| Arafat et al[9] | 3 | Sep 20 | Bangladesh | India | Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Cross-country | Int J of Social Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Challenges of scientific studying | No funding |

| Benker[13] | 1 | Oct 20 | United Kingdom | United Kingdom | Sociology | Sociology | Appetite | Behavioral science | Emergency preparedness | No funding | |

| Chen et al[14] | 7 | Jun 20 | Australia | Australia | Engineering | Engineering | Intracountry | J of Safety Science and Resilience | Disaster | Economics | No funding |

| Dammeyer[15] | 1 | Jul 20 | Denmark | Denmark | Psychology | Psychology | Personality and Individual Differences | Psychology | Individual personality and PB | No funding | |

| Dickins et al[16] | 2 | Oct 20 | United Kingdom | United Kingdom | Psychology | Psychology | Intracountry | Learning and Motivation | Psychology | Uncertainty and PB | No funding |

| Dulam et al[17] | 3 | Apr 20 | Japan | Japan | Engineering | Engineering | Intracountry | J of Advanced Simulation in Science and Engineering | Engineering | Technology and PB | No info |

| Du et al[18] | 4 | Oct 20 | China | China | Psychology | Psychology | Intracountry | Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being | Psychology | Behavioral perspectives | National Natural Science Foundation of China |

| Hall et al[19] | 4 | Jul 20 | New Zealand | New Zealand | Management | Management | Cross-country | J of Service Management | Management | Consumer behavior during a disaster | No info |

| Hao et al[20] | 3 | Aug 20 | China | China | Economics | Economics | Cross-country | China Agricultural Economic Review | Economics | E-commerce’s role on food hoarding | Beijing Municipal Education Commission Social Science |

| Islam et al[21] | 7 | Oct 20 | China | China | Economics and Management | Economics and Management | Cross-country | J of Retailing and Consumer Services | Marketing | Reasons of panic buying | National Social Science Fund of China |

| Jeżewska-Zychowicz et al[22] | 3 | Sep 20 | Poland | Poland | Business | Business | Intracountry | Nutrients | Human nutrition | Behavioral perspectives | Warsaw university of life sciences |

| Kar et al[23] | 3 | Oct 20 | India | India | Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Cross-country | Indian J of Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Behavioral perspectives for Controlling of panic buying | No funding |

| Keane et al[24] | 2 | Aug 20 | Australia | Australia | Health Economics and Marketing | Consumer Behaviour, Econometrics | Intracountry | J of Econometrics | Econometrics | Econometrics model of PB | Australian Research Council grants |

| Kostev et al[25] | 2 | Jul 20 | Germany | Germany | Epidemiology, public health | Epidemiology, public health | Intracountry | J of Psychiatric Research | Psychiatry | Drug purchasing surge during COVID 19 | No funding |

| Laato et al[26] | 4 | Jul 20 | Finland | Norway | Technologies | Economics and management | Cross-country | J of Retailing and Consumer Services | Marketing | Media and panic buying | No info |

| Lins et al[27] | 2 | Sep 20 | Portugal | Portugal | Social psychology | Social psychology | Cross-country | Heliyon | Medical sciences | Measurement instrument | No funding |

| Loxton et al[28] | 6 | Jul 20 | Australia | China | Business | Economics | Cross-country | J of Risk and Financial Management | Finance and Risk | Consumer behavior during disasters | No funding |

| Martin-Neuninger et al[29] | 2 | Jun 20 | New Zealand | New Zealand | Food Policy and Security | Food Policy and Security | Cross-country | Frontiers in Psychology | Psychology | Consumer behaviour | No funding |

| Micalizzi et al[1] | 3 | Oct 20 | United States | United States | Behavioral and Social Sciences | Behavioral and Social Sciences | Intracountry | British J of Health Psychology | Psychology | Hoarding during emergency | National Institutes on Drug Abuse |

| Naeem[30] | 1 | Sep 20 | United Kingdom | United Kingdom | Business administration | Business administration | J of Retailing and Consumer Services | Marketing | Social media and panic buying | No funding | |

| Prentice et al[31] | 3 | Aug 20 | Australia | Australia | Marketing and Consumer Behavior | Marketing and Consumer Behavior | Intracountry | J of Retailing and Consumer Services | Marketing | Government timed-intervention policy and PB | Inspector General Emergency Management Queensland, Australia |

| Rosita[32] | 1 | Oct 20 | Indonesia | Indonesia | Consumer behavior | Consumer behavior | Int J of Multiscience | All disciplines | Consumer behavior | No info | |

| Shorey et al[33] | 4 | Jul 20 | Singapore | Singapore | Nursing | Nursing | Intracountry | Journal of Public Health | Public health | Responses during emergencies | No funding |

| Sim et al[6] | 4 | Apr 20 | Singapore | Singapore | Psychiatry | Psychiatry | Cross-country | Psychiatry Research | Psychiatry | Panic buying distribution | No info |

| Singh et al[34] | 2 | Mar 20 | India | India | Arts humanities & communication | Arts humanities & communication | Intracountry | Studies in Indian Place Names | History | Supply chain | No info |

| Turambi et al[35] | 2 | No info | Indonesia | Indonesia | Economics | Economics | Intracountry | International Journal of Applied Business and International Management | Business | Behavioral perspectives | No info |

| Yuen et al[7] | 4 | May 20 | Singapore | China | Economics and Supply Chain Management | Economics and Supply Chain Management | Cross-country | Int J Environ Res Public Health | Environmental and Public Health | Psychological causes of panic buying | Nanyang Technological University, Singapore |

| Zheng et al[36] | 3 | Mar 20 | China | Hong Kong | Management | Management | Cross-country | Omega | Management | Supply chain | Hongkong & China |

| Tsao et al[37] | 3 | Feb 19 | Taiwan | Taiwan | Industrial management | Industrial management | Intracountry | Industrial Marketing Management | Industrial marketing | Marketing and supply chain | Partially supported by Ministry of Sci and Tech Taiwan |

| Wei et al[38] | 3 | Sep 11 | China | China | Information management | Information management | Intracountry | 2011 International Conference on Management Science & Engineering (18th) | Management Science and Engineering | Social network data mining and PB | No info |

| Fung et al[39] | 2 | Sep 10 | Hong Kong | Hong Kong | Family and Community Health | Family and Community Health | Intracountry | Scandinavian J of Public Health | Public health | Disaster preparedness | No funding |

| Kulemeka[40] | 1 | No info | United States | United States | Business and Economics | Business and Economics | Advances in Consumer Research | Consumer research | Disaster preparedness | No info | |

| Bonneux et al[41] | 2 | Mar 06 | Belgium | Belgium | Public health | Public health | Intracountry | BMJ | Medical sciences | Drug stockpiling | No info |

| Thomas[42] | 1 | Aug 02 | No info | Semiconductor | III-Vs Review | Semiconductor industry | Possible pb in semiconductor industry | No info |

Authors from several disciplines, such as psychiatry, management, economics, business, sales and marketing, consumer behavior, public health, communication, information management, sociology, engineering, business administration, psychology, nursing, health economics, food policy, epidemiology, and community health, have been studied it. Most of the authors were affiliated with institutions from Australia, Bangladesh, China, India, Singapore, and the United States (Table 2). Eighteen papers had cross-country collaboration, and ten were funded projects. The average number of authors per paper was 3.3; Arafat SMY has published the maximum number of papers (6) as the first author on the topic.

The maximum number of papers were published in behavioral health (13: Psychiatry 9; psychology 4), followed by business (including marketing and management) (12), public health (4), and economics (3) (Table 2). Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services hosted the maximum number of papers on PB (4) followed by Psychiatry Research (2).

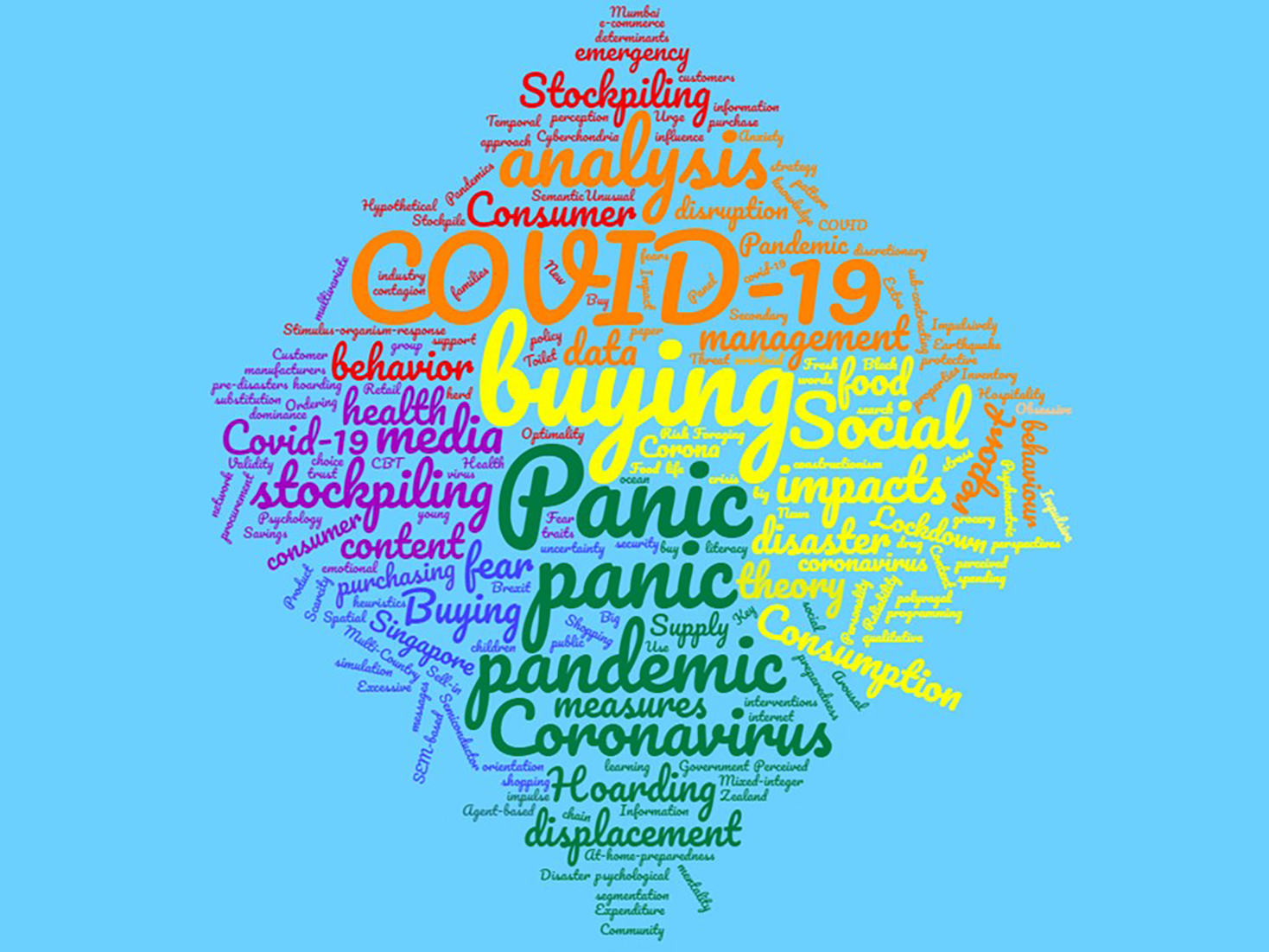

A wide spectrum of keywords was found in articles with a prominence of COVID-19, PB, Coronavirus, and pandemic. Figure 2 shows the word cloud analysis of different keywords extracted from research publications on “panic buying.” Words with a larger font size refer to the most frequently used keywords and vice versa. Different colors are used to differentiate words from each other. Colors do not have any statistical significance.

We aimed to identify the aspects of PB already explored and research trends. We searched PubMed, PMC, Scopus, and GS with the search term “panic buying” on November 15, 2020. A total of 42 articles were collected and scrutinized (Figure 1). The type of research, publishing year, applied method, key findings, geographical distribution of the authors, specialty of authors, collaboration, subject of the journal, and research funding were assessed (Table 1 and Table 2).

The main findings of the review revealed that some aspects of PB have been addressed such as the definition of PB[4], causative model[2], econometric model[21], media reporting of PB[3], responsible factors for PB[2], psychological reasons for PB[5-7], controlling strategy[8], measuring instrument[27], challenges to explore PB[9], and geographical distribution[2]. However, the methods were superficial that instigated further studies to replicate the observations.

The study revealed that more than three-quarters (85.71%) of the research output on PB has occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is an indication of the growing public health relevance of this phenomenon. More than sixty percent (64.28%) of the papers were original contributions indicating that the more empirical studies are coming out gradually (Table 1). Most of the studies applied survey and cross-sectional study design, which may be explained by the pattern of PB as it appears irregularly, episodically, and erratically in response to the adverse stimuli[2,9]. However, longitudinal studies are better in order to explore the behavior. Online media reports, social media, and Google Trends were also used, which may be explained by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the lockdown was applied.

Several studies have looked at the etiological underpinnings of PB, mainly in terms of psychological and social factors that may contribute to the phenomenon[5-7]. The results are intuitive and point to the significance of perception of commodity and time scarcity, sense of uncertainty as well as the herd instinct, which has its basis in the social learning theory, as potential contributors to the genesis of PB[2,5-7]. Further, perceptions of price differential and price fluctuations have been found to correlate with PB behavior; this has implications from a management perspective and highlights the importance of maintaining supply chains.

Little empirical evidence is available on the management of PB. One group of authors proposed an online cognitive behavior therapy model for PB, but it was not tested[23]. The media should play a central role in curbing PB by spreading awareness about the phenomenon and adopting responsible reporting practices. A collaborative approach between the media, government, and health sector would foster a collective sense of responsibility and bring about sustainable changes in reporting practices, a key strategy to control PB[3].

Drawing upon these insights, it appears that PB can be controlled by adequate, timely, and consistent information on the evolving situation with an additional focus on clarifying misinformation or rumors. To reduce visual cues, big retail stores can encourage online shopping at least for those who are young/internet savvy. This will reduce long queues outside shopping stores, which is a visual signal for other buyers to join, and will reduce the possibility of such images being circulated in the mass media and social media, another important cue for PB[10]. Opening fair price shops where commodity prices are tightly regulated may be helpful in curbing panic purchases.

Researchers from several specialties took part in PB research, multiple academic domains have been researched, and articles have been published in several specialty journals such as psychiatry, psychology, business, sales and marketing, public health, supply chain, economics, management, consumer behavior, disaster preparedness, e-commerce, consumer behavior, marketing, prevention strategies, media, social network, economics, communication, information management, sociology, personality, nursing, health economics, food policy, epidemiology, community health, and engineering (Table 2). Consumer behavior patterns have been studied during different situations such as pandemic[28] and seasonally recurring disasters[40]. Insights from these studies can be used to spread awareness about PB, facilitate the identification of hoarders, and take steps to mitigate supply chain disruptions[37]. Reducing conflicting information from different media sources and giving advance information about impending seasonal disasters would assist people in staggering their purchases and reduce eleventh-hour PB. Concordance of information from media sources is likely to promote trust in the media, a key element that has been linked to an increased likelihood of distress purchases[22].

Most of the authors were affiliated with institutions from Australia, Bangladesh, China, India, Singapore, and the United States (Table 2). The fact that more than half of the studies reviewed originated from Asia may reflect the proneness of countries in the region for PB, probably due to a combination of structural issues, public mistrust, and lack of adequate governmental action. More than forty percent (42.85%) of the papers had intercountry collaborations signifying the common interest of the research. Among the 10 funded projects, China had the highest funding (3 full; 1 partial); Australia (2), Hong Kong (1 partial), United States (1), Poland (1), Taiwan (1), and Singapore (1).

This is the first systematic approach to provide an overview and identify the research gaps on the emerging research topic. Only peer-reviewed published articles were reviewed.

The search was done cross-sectionally by a single individual (first author). Only articles published in the English language were included. Preprints were not included.

PB is a relatively newer concept to get the attention of the research community. The study revealed several important aspects of PB research including research trends, major studied areas, geography, collaboration, and funding of studies. This review would help policymakers, researchers, funders, and other stakeholders to shape their decision while studying PB. Further robust studies with replication of the findings are warranted to fill the research gaps identified in this review.

Panic buying is an under-addressed research entity.

Sporadic evidence is coming out in recent days.

We aimed to see the perspectives of panic buying that have been studied through November 15, 2020.

We did a systematic search in PubMed, PubMed Central, Scopus, and Google Scholar and reviewed 42 articles.

The study identified the distribution of study, aspects of panic buying, academic domain related to panic buying, distribution of authors, the specialty of the authors and journals, funding, and collaborations of the identified articles.

Although the study identified some important perspectives, further studies are warranted in a systematic manner.

The review provides a good insight into the different stakeholders to plan further studies and prevent panic buying.

| 1. | Micalizzi L, Zambrotta NS, Bernstein MH. Stockpiling in the time of COVID-19. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Menon V, Alradie-Mohamed A, Mukherjee S, Kaliamoorthy C, Kabir R. Responsible Factors of Panic Buying: An Observation From Online Media Reports. Front Public Health. 2020;8:603894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Menon V, Marthoenis M, Sharma P, Alradie-Mohamed A, Mukherjee S, Kaliamoorthy C, Kabir R. Media portrayal of panic buying: A content analysis of online news portals. Glob Psychiatry. 2020;3:249-54. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Menon V, Kaliamoorthy C, Mukherjee S, Alradie-Mohamed A, Sharma P, Marthoenis M, Kabir R. Panic buying: An insight from the content analysis of media reports during COVID-19 pandemic. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. 2020;37:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Marthoenis M, Sharma P, Hoque Apu E, Kabir R. Psychological underpinning of panic buying during pandemic (COVID-19). Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Sim K, Chua HC, Vieta E, Fernandez G. The anatomy of panic buying related to the current COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:113015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yuen KF, Wang X, Ma F, Li KX. The Psychological Causes of Panic Buying Following a Health Crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Arafat SMY, Kar SK, Kabir R. Possible Controlling Measures of Panic Buying During COVID-19. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020;1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Arafat SY, Kumar Kar S, Shoib S. Panic buying: Is it really a problem? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020: 20764020962539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Ahmed RR, Streimikiene D, Rolle JA, Pham AD. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Antecedants for the Impulse Buying Behavior of US Citizens. J Competitiveness. 2020;12:5-27. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Alchin D. Gone with the Wind. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28:636-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alfa AB, Gomina MO. Effect of Panic Buying on Individual Savings: The Covid-19 Lockdown Experience. Lapai J Econ. 2020;4:69-80. |

| 13. | Benker B. Stockpiling as resilience: Defending and contextualising extra food procurement during lockdown. Appetite. 2021;156:104981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen Y, Rajabifard A, Sabri S, Potts KE, Laylavi F, Xie Y, Zhang Y. A discussion of irrational stockpiling behaviour during crisis. J Safety Sci Resilience. 2020;1:57-58. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dammeyer J. An explorative study of the individual differences associated with consumer stockpiling during the early stages of the 2020 Coronavirus outbreak in Europe. Pers Individ Dif. 2020;167:110263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dickins TE, Schalz S. Food shopping under risk and uncertainty. Learn Motiv. 2020;72:101681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dulam R, Furuta K, Kanno T. Development of an agent-based model for the analysis of the effect of consumer panic buying on supply chain disruption due to a disaster. J Adv Simulat Sci Eng. 2020;7:102-116. |

| 18. | Du H, Yang J, King RB, Yang L, Chi P. COVID-19 Increases Online Searches for Emotional and Health-Related Terms. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hall MC, Prayag G, Fieger P, Dyason D. Beyond panic buying: consumption displacement and COVID-19. J Serv Manag. 2020;. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Hao N, Wang HH, Zhou Q. The impact of online grocery shopping on stockpile behavior in Covid-19. China Agr Econ Rev. 2020;12:459-570. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Islam T, Pitafi H, Wang Y, Aryaa V, Mubarik S, Akhater N, Xiaobei L. Panic Buying in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-Country Examination. J Retail Consum Serv. 2020: 102357. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Jeżewska-Zychowicz M, Plichta M, Królak M. Consumers’ Fears Regarding Food Availability and Purchasing Behaviors during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Importance of Trust and Perceived Stress. Nutrients. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kar SK, Menon V, Arafat S M. Online group cognitive behavioral therapy for panic buying: Understanding the usefulness in COVID-19 context. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:607-609. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Keane M, Neal T. Consumer panic in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Econom. 2021;220:86-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kostev K, Lauterbach S. Panic buying or good adherence? J Psychiatr Res. 2020;130:19-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Laato S, Islam AN, Farooq A, Dhir A. Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. J Retail Consum Serv. 2020;57:102224. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lins S, Aquino S. Development and initial psychometric properties of a panic buying scale during COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Loxton M, Truskett R, Scarf B, Sindone L, Baldry G, Zhao Y. Consumer behaviour during crises: Preliminary research on how coronavirus has manifested consumer panic buying, herd mentality, changing discretionary spending and the role of the media in influencing behaviour. J Risk Financial Manag. 2020;13:166. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Martin-Neuninger R, Ruby MB. What Does Food Retail Research Tell Us About the Implications of Coronavirus (COVID-19) for Grocery Purchasing Habits? Front Psychol. 2020;11:1448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Naeem M. Do social media platforms develop consumer panic buying during the fear of Covid-19 pandemic. J Retail Consum Serv. 2020;58:102226. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Prentice C, Chen J, Stantic B. Timed intervention in COVID-19 and panic buying. J Retail Consum Serv. 2020;57:102203. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rosita R. Panic Buying In The Covid–19 Pandemic Era In Indonesia. Inter J Multi Sci. 2020;1:60-70. |

| 33. | Shorey S, Ang E, Yamina A, Tam C. Perceptions of public on the COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore: a qualitative content analysis. J Public Health (Oxf). 2020;42:665-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Singh CK, Rakshit P. A Critical Analysis to comprehend Panic buying behaviour of Mumbaikar’s in COVID-19 era. Stu Ind Place Names. 2020;40:44-51. |

| 35. | Turambi RD, Wuryaningrat NF. Panic Buying Perception in Walian Satu Sub-District, Tomohon City. IJABIM. 2020:1-7. |

| 36. | Zheng R, Shou B, Yang J. Supply disruption management under consumer panic buying and social learning effects. Omega. 2020: 102238. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Tsao YC, Raj PVRP, Yu V. Product substitution in different weights and brands considering customer segmentation and panic buying behavior. Ind Mark Manag. 2019;77:209-220. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Wei K, Wen-Wu D, Lin W. Research on emergency information management based on the social network analysis—A case analysis of panic buying of salt. In: 2011 International Conference on Management Science & Engineering 18th Annual Conference Proceedings. 2011 Sep 11-15; Rome, Italy. IEEE, 2011: 1302-1310. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Fung OW, Loke AY. Disaster preparedness of families with young children in Hong Kong. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:880-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kulemeka O. US consumers and disaster: Observing “panic buying” during the winter storm and hurricane seasons. ACR North Am Advances. 2010;. |

| 41. | Bonneux L, Van Damme W. An iatrogenic pandemic of panic. BMJ. 2006;332:786-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Thomas A. Panic buying ahead? III-Vs Review. 2002;15:2. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Behavioral Sciences

Country/Territory of origin: Bangladesh

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Neal T, Shi RH S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH