Published online Apr 30, 2019. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v7.i4.142

Peer-review started: March 19, 2019

First decision: April 18, 2019

Revised: April 22, 2019

Accepted: April 23, 2019

Article in press: April 23, 2019

Published online: April 30, 2019

Processing time: 43 Days and 8.2 Hours

Maspin or SerpinB5, a member of the serine protease inhibitor family, was shown to function as a tumor suppressor, especially in carcinomas. It seems to inhibit invasion, tumor cells motility and angiogenesis, and promotes apoptosis. Maspin can also induce epigenetic changes such as cytosine methylation, de-acetylation, chromatin condensation, and histone modulation. In this review, a comprehensive synthesis of the literature was done to present maspin function from normal tissues to pathologic conditions. Data was sourced from MEDLINE and PubMed. Study eligibility criteria included: Published in English, between 1994 and 2019, specific to humans, and with full-text availability. Most of the 118 studies included in the present review focused on maspin immunostaining and mRNA levels. It was shown that maspin function is organ-related and depends on its subcellular localization. In malignant tumors, it might be downregulated or negative (e.g., carcinoma of prostate, stomach, and breast) or upregulated (e.g., colorectal and pancreatic tumors). Its subcellular localization (nuclear vs cytoplasm), which can be proved using immunohistochemical methods, was shown to influence both tumor behavior and response to chemotherapy. Although the number of maspin-related papers increased, the exact role of this protein remains unknown, and its interpretation should be done with extremely high caution.

Core tip: The present paper concentrated on showing different patterns of immunohistochemical expression and mRNA levels of maspin, as presented in published studies from 1994 until the beginning of 2019 that were included in the PubMed database. It was shown that maspin, a member of the serine protease inhibitor family, functions as a tumor suppressor or tumor promoter. Its function is organ-related and depends on its subcellular localization. In colorectal cancer specimens, maspin was a helpful marker of budding assessment. In most of the malignant tumors, it was demonstrated to be an independent prognostic and predictive factor.

- Citation: Banias L, Jung I, Gurzu S. Subcellular expression of maspin – from normal tissue to tumor cells. World J Meta-Anal 2019; 7(4): 142-155

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v7/i4/142.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v7.i4.142

Maspin, also known as SerpinB5, is a member of the serine protease inhibitor family, which was identified by Zou et al[1] in 1994[2-4]. In most of the studies, it acted as a tumor suppressor through inhibitory effects on invasion, motility, and angiogenesis and through stimulation of a mitochondrial apoptosis pathway[1-4]. This negative impact on tumor cells is supposed to be p53-linked[5].

Maspin can also induce epigenetic changes like cytosine methylation, de-acetylation, chromatin condensation, or histone modulation[3]. Recent in vitro studies focused on maspin secretion[6,7]. These studies tried to prove that maspin is a soluble free or an exosome cargo protein, which might be chemically synthesized and used as a future medical drug[6,7]. In vitro, maspin influenced the peritumoral micro-environment by enhancing macrophage secretion of inflammatory cytokines[6,7].

In the human body, maspin is expressed in many tissues or organs and is down or upregulated in malignant tumors. As maspin shows different subcellular localizations (cytoplasmic and nuclear), in both normal and tumor tissues, it is difficult to app-reciate its exact role in tumorigenesis, tumor invasion, or progression[8]. The aim of this review was to perform a complex synthesis regarding maspin expression in different organs, from normal tissue to non-tumor disorders and malignant transformation. The organ-related subcellular expression was also emphasized.

The present paper represents a narrative review of the literature on the serine protease inhibitor maspin, focusing mainly on its immunohistochemical (IHC) expression in different tissues and pathologic processes.

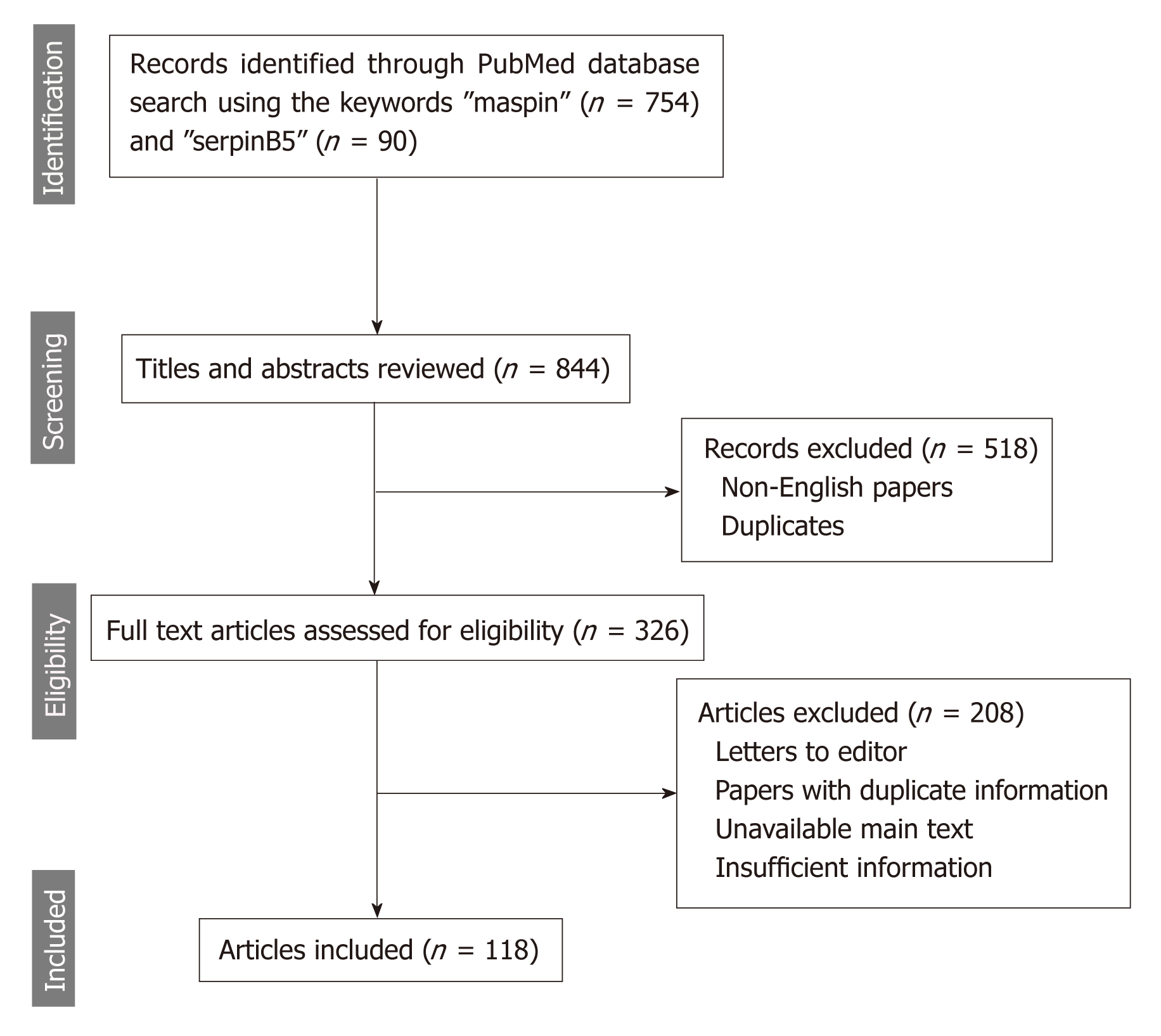

The online search consisted of browsing the PubMed/MEDLINE database using the MeSH terms and keywords “maspin” and “serpinB5” to identify articles published between 1994 and the beginning of 2019. Eligible for inclusion were only publications written in English, studies for human species, and with full-text availability (Figure 1).

Besides the detailed presentation of data, summary tables regarding maspin immunoexpression in different organs in various conditions were constructed based on the data published in the included articles (Tables 1-3).

| Organ/ tissue | Subcellular expression in normal tissue | Subcellular expression in pathologic conditions |

| Placenta | Cytoplasm: Syncytio- and cytotrophoblasts, and endothelial cells; Nucleus: Chorionic plate | Preeclampsia: Upregulation |

| Mammary gland | Cytoplasm: Myoepithelial cells (intense in pregnancy and lactation); Nucleus: Myoepithelial cells | Invasive breast cancer: Maspin positivity is more frequent in ductal than lobular carcinomas; Cytoplasm only: Negative prognostic indicator, ER and PgR negativity; Nucleus: Better prognosis, ER and PgR positivity; Negativity: Loss or cytoplasm to nuclear translocation in metastatic tissue |

| Ovary | Negative | Benign tumors: Negative or infrequent nuclear; Ovarian carcinomas: Cytoplasm only: Cisplatin sensitivity; Mixed expression (cytoplasm and nucleus): Indicator of low malignant potential |

| Uterine cervix | Squamous epithelium: Cytoplasmic and nuclear staining | CIN3: Cytoplasm: Down regulation; Nucleus: Upregulation; Squamous cell carcinoma: Cytoplasm: Tumor suppressor role; Adenocarcinoma: Cytoplasm: Aggressive behavior |

| Uterine body | Negative or positive (mostly nuclear) staining in normal endometrial glands; Low intensity in atrophic endometrium | Endometrial hyperplasia: Nucleus: Indicator of atypia; Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma: Cytoplasm: Aggressive behavior; Nucleus: Better prognosis |

| Prostate | Basal cells: Positive; Secretory cells: Negative | HGPIN: Basal cells: Positive (same intensity as normal); Secretory cells: Positive; Adenocarcinoma: Low-grade carcinoma: Reduced expression compared with HGPIN; High-grade carcinoma: Low or no expression |

| Urinary bladder | Positive in epithelial cells | Urothelial carcinoma: Nucleus: Better prognosis |

| Organ/ tissue | Subcellular expression in normal tissue | Subcellular expression in pathologic conditions |

| Lung | Bronchial basal cells: Nuclear staining; Alveolocytes: Negative | Non-small cell carcinomas: Cytoplasm only: Negative prognostic factor; Nucleus only: Low aggressivity |

| Esophagus | Squamous epithelium: Negative or weak cytoplasm | SCC: Nucleus: Low pTNM stage; Cytoplasm: Risk for lymph node metastases |

| Stomach | Foveolar and glandular cells: Cytoplasm or negative | Dysplasia: Nucleus: High-grade dysplasia; Carcinomas: Cytoplasm: Better prognosis; Nuclear: Local aggressive behavior; Negative: Risk for distant metastases or neuroendocrine component |

| Colon and rectum | Normal mucosa: Cytoplasm or negative | Dysplasia: Nucleus: High-grade dysplasia; Adenocarcinoma: Cytoplasm only: Low-grade tumor, low risk for metastases, high chance for MSI-H status; Nuclear only: High pTNM stage, high-grade budding; Negative: Risk for distant metastases or neuroendocrine component |

| Liver and intrahepatic biliary ducts | Negative in most of the normal hepatocytes and in normal biliary ducts | Carcinoma: Positive (cytoplasmic, nuclear or mixed cyto-nuclear expression), with unknown significance |

| Pancreas | Negative in exo- and endocrine pancreas | PanIN grade 1 and grade 2: Negative; PanIN grade 3 and PDAC: Positive (cytoplasmic and nuclear staining); Endocrine tumors: Negative; Ductal adenocarcinoma: Nuclear |

| Gallbladder | Negative or positive (cyto-nuclear staining) | Dysplasia: Negative or weak staining; BilIN, carcinoma: Cyto-nuclear expression gradually increases from normal epithelium to BilIN and carcinoma |

| Organ/ tissue | Subcellular expression in normal tissue | Subcellular expression in pathologic conditions |

| Brain | Positive in nucleus and cytoplasm | Decreased expression in parallel with the advancing glioma stage |

| Head and neck | Cytoplasm: Oral cavity epithelium and temporal bone; Nucleus: Salivary glands: Myoepithelial cells, basal cells of the ducts and some luminal cells; Negative: Salivary glands: Secretory cells | Oral SCC: Cytoplasm (better prognosis); Temporal bone SCC: Negative, cytoplasm-only or cyto-nuclear; Salivary glands: Pleomorphic adenoma (cyto-nuclear or cytoplasmic only), Warthin’s tumor (cyto-nuclear or cytoplasmic only, weaker than in pleomorphic adenoma), adenoid cystic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma (cytoplasmic only, negative in an anaplastic variant of adenoid cystic carcinoma); Laryngeal SCC: Cytoplasm and nucleus |

| Thyroid | Negative | Negative follicular adenoma, follicular carcinomas, poorly and undifferentiated carcinomas; Cytoplasm: Papillary thyroid carcinoma |

| Skin | Cytoplasmic: Normal epidermis; Nuclear: Myoepithelial cells of the sweat glands and mature sebaceous glands | SCC: Cytoplasm expression in low stages and nuclear staining in dedifferentiated tumors; Basal cell carcinoma: Cytoplasm and nucleus; Melanoma: Nuclear expression is an indicator of aggressiveness |

| Soft tissue | Negative | Inflammation: Negative; Lipoma, atypical lipomatous tumor: Cytoplasm; Sarcomas: Cytoplasm or nucleus, as indicators of aggressive behavior |

Dokras et al[9] first evaluated IHC expression and mRNA levels of placenta maspin, in 2002. Placentas obtained after first and second trimester pregnancy and after caesarian deliveries at term were included in their observations. The maximum values of maspin mRNA level were detected in the third trimester of pregnancy. On the other hand, negative expression was observed in the immortalized first trimester cytotrophoblasts and choriocarcinoma cell lines with high invasive ability. Similar to the mRNA levels, IHC expression showed patchy staining of the cytotrophoblastic layer in the first trimester, uniform cyto- and syncytiotrophoblastic layers in the second trimester, and more intense expression in the third trimester[9] (Table 1).

In preeclamptic (PE) placentas, both mRNA and protein levels were upregulated (Table 1) and correlated with modifications observed with Hematoxylin and Eosin stain[10]. It was intimal enlargement of the vessel wall, thickening of the syncy-tiotrophoblast membranes, and increased number of syncytial knots. It was concluded that hypomethylation of the maspin promoter might be the causal factor of the increased expression of maspin in PE placentas[10].

Qi et al[11] evaluated the plasmatic level of unmethylated maspin DNA in a population consisting of women with normal pregnancies, PE, and gestational trophoblastic disease. Unmethylated maspin DNA was not detected in healthy nonpregnant women and in those with the trophoblastic gestational disease. The level was higher in women with severe PE than in those with normal third trimester pregnancies and presented a gradual increase with the gestational age[11].

Methylated and unmethylated maspin DNA blood concentrations may be useful for identification of noninvasive fetal trisomy 18 beginning in the first trimester[12]. Methylation of the maspin gene induces downregulation of maspin protein expression and subsequently inhibits migration and invasion of the first trimester extravillous trophoblast cell line through interaction with the proangiogenic factors such as mismatch repair proteins (e.g., MMP2) or vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF-A and VEGF-C)[13]. This interaction might lead to the occurrence of PE[13].

Regarding maspin subcellular localization, nuclear expression was limited to the chorionic plate with significant downregulation in the extravillous trophoblasts[14]. Cytoplasmic positivity can be seen in endothelial cells and trophoblasts[9,14] (Table 1).

Maspin expression was evaluated in both normal tissues, especially during pregnancy and carcinomas of the mammary gland[15-20]. In late pregnancy, a peak of expression is seen during lactation and the level decreases and remains constant after the lactation period[20]. Almost all cells presented cytoplasmic staining with infrequent nuclear positivity (Table 1), which can be an indicator of epithelial growth factor induced maspin phosphorylation[20].

In breast carcinomas, there are several maspin-related studies, but in most of them no data about the subcellular localization of staining were included. In these tumors, maspin IHC positivity (independently by the localization) was directly correlated with larger tumor size, younger age, high histologic grade, negative expression of estrogen receptor and/or progesterone receptor, positivity for p53, and a lymphocyte-rich stroma[15-18]. In other studies, it was hypothesized that maspin is not involved in breast cancer histogenesis, at least in those carcinomas with extremely aggressive behavior[21].

Examination of the subcellular localization (Table 1) revealed that maspin cyto-plasmic positivity is observed in 36% of invasive ductal carcinomas and 7% of lobular carcinomas, the latter being mostly maspin-negative[18,21]. The nuclear expression is related with estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positivity, while the cytoplasmic location is an indicator of negativity for hormone receptors, high S-phase fraction, and aneuploidy[19]. Maspin cytoplasmic positivity was suggested to be a poor prognostic indicator of invasive breast cancer, independently of the histologic subtype[19].

Machowska et al[22] presented nuclear location as a better prognostic factor in cases with invasive ductal carcinoma. Nuclear positivity was an indicator of Ki-67 negativity or low expression[22]. In a study by Strien et al[23], which compares luminal subtype A and B breast cancers, it was shown that maspin expression was lost in metastases, in the majority of maspin-positive primary tumors, or presented translocation from cytoplasmic to nuclear positivity. No differences between subtype A and B were noted.

Wakahara et al[24], examining four categories of maspin expression [cytoplasmic only, nuclear only, mixed (cytoplasm + nuclei), and negative] and their correlations with histone deacetylase 1, showed that maspin cytoplasmic only represents an independent negative prognostic factor, thus being an indicator of higher histological grade, negative progesterone receptor expression, shorter disease-free survival, and higher histone deacetylase 1 compared with the mixed expression group. They suggested that inhibition of histone deacetylase 1 could represent an inhibitory mechanism for maspin[24].

Recently, Umekita et al[25] demonstrated that maspin mRNA expression in sentinel lymph nodes represents an independent factor of nonsentinel lymph node metastasis. Maspin was shown to act upon peritumoral stroma and to increase collagen pro-duction as a cause for doxorubicin resistance[26].

Ovary: Expression of maspin was not present in the normal ovary[27-30]. In ovarian carcinomas, maspin expression in over 50% of the tumor cells was associated with higher tumor grade, positive peritoneal effusion cytology, lower survival rate, and positivity for the proangiogenic factors VEGF-A, -C, and -D[27,28]. Most of the malignant tumors presented with cytoplasmic only expression, but those with low malignant potential showed mixed positivity (cytoplasm and nucleus)[29]. The localization of maspin expression might have therapeutic importance because the cytoplasmic positivity associates with cisplatin sensitivity[30] (Table 1).

Uterine cervix: Maspin is expressed both in the cytoplasm and nucleus of the normal squamous cervical epithelium[31,32]. The cytoplasmic expression is downregulated in premalignant disorders such as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and even more downregulated from microinvasive to invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)[31,32].

In SCC, cytoplasmic maspin can be colocalized with cytoplasmic testisin, a serine protease normally found in testicular germ cells, which inhibits the tumor suppressor activity of maspin[33]. Maspin positivity is correlated with advanced stage, increased lymphatic microvessel density, and the presence of lymph node metastases[31,32]. Nuclear expression increases in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 but significantly decreases in SCC cells[31,32]. Maspin expression is decreased or lost in intravascular emboli from SCCs[31,32]. In adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix, cytoplasmic expression of maspin was found to be an indicator of aggressive beha-vior[34] (Table 1).

Uterine body: The normal endometrium is maspin negative or localizes to the nucleus[35-37]. Maspin is positive in most of the cases diagnosed as atypical hyperplasia or endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (nuclear and/or cytoplasmic staining). Maspin expression is also correlated with lymph node metastases and FIGO stage in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma[35-37]. Nuclear subcellular localization was correlated with squamous cell differentiation of endometrioid endometrial ade-nocarcinoma and with better prognosis, while concurrent cytoplasmic positivity represents an indicator of a more aggressive tumor[36,38] (Table 1).

Prostate gland: In normal prostate, maspin marks basal but not secretory cells[39-43]. Its expression is upregulated in high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and downregulated during progression to invasive carcinoma[41] (Table 1). In prostate carcinomas, maspin exerts a tumor suppressing role[39,40]. Negative or decreased IHC expression was correlated with p53 positivity and a higher tumor grade and stage[39,40] (Table 1).

Positive immunostaining was noted in tumors that showed a histological response to therapy administered before prostatectomy[39,40]. Maspin also proved its ability to enhance the sensitivity of hormone-resistant prostate cancer cells to curcumin treatment by modulating levels of proapoptotic proteins Bad and Bax[42]. The experi-mental studies proved that maspin can influence prostate carcinoma host immune response through stimulation of neutrophil maturation at both the systemic and intratumoral levels along with antibody-dependent cytotoxicity and decreased lymphatic vessels formation[43].

Urinary bladder: In normal bladder, maspin expression can be seen in epithelial cells[44-47]. Maspin downregulation in bladder carcinoma cells has been shown to be significantly associated with a lower progression-free survival rate[44-46] (Table 1). Elevated levels inhibited proangiogenic factors such as insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 or VEGF-C and upregulated the apoptosis rate of cancer cells[44-46]. Maspin increased the sensitivity of bladder cancer cells to cisplatin therapy by enhancing its inhibitory effect on tumor cell proliferation[44-46].

Induction of maspin was suggested to be the mechanism through which Prostate-derived E-twenty six factor (decreased in tumor cells compared with the normal bladder) inhibit tumor development and invasion along with repressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition by upregulating E-cadherin expression and downregulating vimentin, SNAIL, SLUG, and N-cadherin[47].

Studies of IHC expression observed contradictory results. In some studies, maspin was mostly positive in low-grade tumors and associated with better survival. Others showed an important increase in maspin expression in high-grade bladder tumors[8].

In normal bronchial cells, maspin expression can be seen in the nuclei of basal cells[48-52]. In non-small cell carcinomas, both SCC and adenocarcinomas, subcellular localization of maspin proved to be correlated with some clinicopathological parameters (Table 2).

Cytoplasmic expression was an independent negative prognostic indicator and was correlated with the micropapillary component, higher pTNM stage, shorter disease-free survival, and low disease-specific survival[48-51]. On the other hand, nuclear only staining (without synchronous cytoplasm positivity) was correlated with earlier pathological stage, absence of aggressive invasion, and negative p53[48-51]. Maspin mRNA expression appeared to be upregulated in adenocarcinoma cells compared to the adjacent normal lung with higher levels of mRNA in advanced stages[52].

Esophagus: Maspin can show infrequent cytoplasmic positivity in squamous cell epithelium[53-55] (Table 2). In SCC cells, downregulation of maspin was noted compared with the adjacent normal epithelium. Strong nuclear staining is associated with favorable prognosis, increased patient survival, and a lower pTN stage while high cytoplasmic staining correlates with the presence of lymph node metastases[53,54]. Based on an in vitro study, which used esophageal SCC cell lines, it was hypothesized that the inhibitory effect of maspin is based on switching the metabolic phenotype to low glycolysis through disrupting the hypoxia inducible factor 1α[55].

Stomach: Maspin expression can be absent or in the cytoplasm of normal epithelium and increases in gastric epithelial cells with intestinal metaplasia likely as a result of demethylation of the maspin gene promoter[56-62]. Nuclear maspin marks cells with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and is one of the factors that plays a role in the progression of intramucosal clusters of signet ring cells to signet ring cell carcinoma, especially multifocal carcinomas[57,58] (Table 2).

In gastric adenocarcinoma cells, maspin expression can be lost, which is an indi-cation of a high risk for distant metastases[21,59]. Complete loss of maspin was also observed more frequently in elderly patients, poorly cohesive carcinomas, and poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas located in the distal part of the stomach[58-61]. Maspin is negative in neuroendocrine components of adenocarcinomas and is not involved in tumorigenesis of gastric neuroendocrine tumors[62].

Cytoplasm only staining is rarely seen in clinical practice in poorly cohesive carci-nomas[58]. In adenocarcinomas, cytoplasm expression is as an indicator of lower pTNM stage and high angiogenic phenotype and correlates with positivity for p53, Bax, Ki-67 and E-cadherin[58].

Nuclear positivity (with or without associated cytoplasm expression) is predomi-nant in undifferentiated intestinal type carcinoma and poorly cohesive carcinoma[58]. Nuclear positivity is associated with locally aggressive behavior and high risk for lymph node metastases and is more frequent in young patients[21,58,59,62]. It is associated with Bax, p53, and Ki-67 negativity and lower angiogenesis[58]. In daily practice, we use nuclear maspin for a better approach of the depth of invasion (pT stage) of poorly cohesive carcinomas (personal unpublished observations).

Colon and rectum: Similar to the gastric epithelium, in colorectal segments maspin expression can be absent or present in the cytoplasm of normal epithelium and increases in epithelial cells with high-grade dysplasia[62-73]. Maspin serum levels are increased in patients with high-grade dysplasia and carcinomas and might be used as an indicator for colonoscopy[69,70].

In colorectal segments, maspin does not mark neuroendocrine tumors[62], but its subcellular expression has a great value in the assessment of adenocarcinomas[72,73]. Although there are studies that proved that maspin expression is correlated with carcinoembryonic antigen serum levels, infiltrative borders, and high histological grade and stage in colorectal adenocarcinomas[65], few articles regard maspin subcellular expression. We use this marker for daily diagnosis and data showed in this review are based on personal observations (over 200 cases were revised) and literature data (Table 2).

Maspin cytoplasmic only positivity is correlated with the absence or a low number of lymph node metastases, low-grade buddings, and absence of p53 positivity[72,73]. It is important to consider a case with cytoplasmic only staining is necessary to have no nuclear positivity (in both tumor center and invasion front).

Maspin nuclear staining is an indicator of aggressive tumor behavior, high tumor grade, high budding grade, high pTNM stage, high risk of local recurrence, or lymph node metastases and absence of peritumoral lymphoid reaction and p53 and VEGF-A positivity[63,64,72,73]. As the maspin nuclear expression is characteristic for tumor buds[73], we use this marker to diagnose patients because maspin is more efficient than cytokeratins (personal observations). For stage II and III colon cancer patients, nuclear maspin staining is an independent predictor of sensitivity for adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and levamisole[67,68,74].

Although it was postulated that elevated nuclear maspin is associated with microsatellite instability[63], we observed that it is associated with low microsatellite instability. The high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) cases usually show cytoplasmic or mixed (cyto-nuclear) maspin positivity[72]. In a few cases, nuclear predominance can be seen in MSI-H cases, but this pattern is observed in p53 negative carcinomas only[74]. It was even suggested that MSI-H carcinomas with nuclear maspin might respond to 5-fluorouracil-based therapy[74]. For patients who received preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, maspin should be downregulated as a result of chemotherapeutic influence[66].

Combining the microsatellite status with BRAF mutation and IHC expression of p53 and maspin, a classification of colorectal cancer was proposed with the best prognosis attributed to MSI-H/BRAF mutated/p53 negative cases with a high number of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and cytoplasmic maspin expression[71]. Cases with the worst prognosis were described as those being MSS/BRAF muta-ted/p53 positive with low tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and nuclear maspin staining predominance[71]. Similar to gastric carcinomas, loss of maspin expression is an indicator of a neuroendocrine component or high risk for distant metastases[72].

Liver and intrahepatic bile ducts: Maspin infrequently marks hepatocytes and biliary epithelium[75-78]. It is downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Table 2), but the exact mechanism is still unknown. Maspin downregulation can be the result of activation of inhibitor κB kinase α by HBx protein and can induce chemoresistance[75]. Decreased maspin expression along with increased VEGF-A expression may be induced by overexpression of chloride intracellular channel 1[76]. Yang et al[77] identified a correlation between patients with a C allele polymorphism of maspin rs2289520 and high Child-Pugh grade (B/C)[77].

In intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas, a delayed progression was shown to be the benefit of maspin and Bax coexpression[78].

Pancreas: Normal pancreatic ducts, Langerhans islets, endocrine tumors, and low-grade lesions of the pancreas do not express maspin[79-82]. Maspin is localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus of the premalignant lesions such as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) grade 3 and also in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (with/without cystic changes; with/without mucinous component) (Table 2) along with strong expression of carcinoembryonic antigen and p53[79-82].

In chronic pancreatitis, which causes diagnostic problems, the presence of an unmethylated maspin promoter can be used to differentiate this lesion from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)[83]. In a recent meta-analysis, maspin and trefoil factor 1 were found to display significantly higher blood plasma levels in PDAC compared to normal tissue[84]. Overexpression of maspin was confirmed by RT-PCR in PDAC and normal adjacent pancreatic tissue[85].

Gallbladder: Although maspin is mostly negative in normal epithelium, it might be helpful for differentiating a malignant tumor from atypical reactive changes of the bile ducts (Table 2) in combination with p53[86-91]. Maspin shows gradually increasing cyto-nuclear expression from regenerative atypia to biliary intraepithelial neoplasia with significant upregulation in carcinomas[86]. The stepwise rise in maspin level from normal epithelium to gallbladder carcinoma is also reflected in its mRNA level[87].

For bile duct biopsy specimens, the use of an immunomarkers complex was also proposed consisting of maspin, insulin-like growth factor-II mRNA binding protein-3, S100P, and von Hippel-Lindau gene product. Positive reactions for maspin, S100P, insulin-like growth factor-II mRNA binding protein-3 along with negativity for von Hippel-Lindau gene product was suggested as a specific staining pattern for bile duct adenocarcinoma[88,89]. Double IHC expressions for maspin (nuclear and cytoplasmic) and claudin-18 (membrane) may improve the diagnostic sensitivity to differentiate a bile duct carcinoma from a ductal adenocarcinoma[90]. This combination was also proposed for distinguishing biliary intraepithelial neoplasia from non-neoplastic changes[91].

Normal brain tissue strongly expresses maspin in the cytoplasm and nucleus and is downregulated in parallel with increasing glioma grade (Table 3) possibly by maspin promoter methylation[92,93].

Maspin expression is observed in the cytoplasm or nuclei of salivary glands (myo-epithelial cells) and also in oral cavity epithelium[94-105] (Table 3). Maspin mRNA was identified in the corneal layers and stroma where it may exert adhesion regulatory functions between the cells and matrix molecules and where it may play a role in wound healing through regulation of the activated fibroblasts migration[105]. In inflammation, maspin was hypothesized to be an indicator of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. It was downregulated in comparison with the noninvasive type and with chronic rhinosinusitis for both cyto-plasm and nucleus[104]. Nuclear reaction and a higher intensity of maspin staining were associated with benign lesions of the salivary glands[102,103].

No significant differences in maspin expression were discovered between recurrent and nonrecurrent ameloblastoma and/or ameloblastic carcinoma[94]. After studying the maspin gene in a large number of participants, it was found that heterozygous T-C of rs17071138 polymorphism and G-G homozygotes or heterozygotes of rs2289520 increase the susceptibility to oral cancer development[95,96]. IHC-based studies on SCC of the oral cavity and tongue emphasized an association between high maspin expression and better overall survival, while the absence of maspin was correlated with high pT stage and presence of lymph node metastases[97-99].

In the temporal bone SCC cases, cytoplasmic subcellular localization of maspin expression was significantly higher in the recurrence-free group, thus representing a potential prognostic marker[100]. For laryngeal SCC, a separate evaluation of cytoplasmic and nuclear immunostaining has led to an association of the nuclear positivity with a longer disease-free interval after surgery[101].

Thyroid: Maspin is one of the six gene panel proposed for distinguishing normal thyroid from papillary thyroid carcinoma, along with TIMP3, RARB2, RASSF1, TPO, and TSHR[106]. In a study by Boltze et al[107], positive maspin immunoreaction (cytoplasm and nucleus) was observed in papillary thyroid carcinomas, while the normal thyroid tissue, follicular adenomas, follicular carcinomas, and poorly and undifferentiated carcinomas were negative (Table 3). The study also presented maspin promoter methylation as a factor of the silencing mechanism of the dedifferentiation degree[107].

Skin: Normal epidermis and sweat or sebaceous glands are maspin positive[108-111]. In SCCs, translocation of maspin immunoexpression from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in the front of invasion was seen as an indicator of tumor dedifferentiation[108,111] (Table 3). All well-differentiated tumors and all cases diagnosed in pT1 stage presented cytoplasmic maspin expression only[108].

The PCR-related studies showed maspin downregulation in tumor tissues compared with the normal adjacent cutis showing the potential role of maspin in tumor development inhibition[109]. Basal cell carcinoma cells variably express maspin at the cytoplasm and nucleus in the center of the nodules especially in nodular basal cell carcinoma[110]. Although infrequently observed, nuclear maspin can be seen in Merkel carcinoma cells, especially in sun-exposed areas[111]. A sun-activated maspin-induced DNA damage was hypothesized[111].

In melanoma cases, a significant association of nuclear maspin staining with aggressive tumor behavior and shorter disease-free survival was shown, while cytoplasmic predominance was present in superficial spreading melanoma[111,112]. High maspin intensity in the invasive margins of primary melanomas was correlated with an unfavorable prognosis[113].

Soft tissues and joints: Although it can act as a proangiogenic marker, maspin expression is negative in soft tissue structures and does not mediate osteoarthritis[114]. For malignant soft tissue tumors, cytoplasmic expression of maspin was correlated with higher histological grade and risk for distant metastasis[115]. In liposarcomas, maspin and VEGF-A seem to be angiogenic promoters[116]. Negative staining was observed for most soft tissue tumors such as granular cell (Abrikossoff) tumor[117], but also for other mesenchymal tumors such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors[118].

Although several studies tried to elucidate parts of the molecular journey in which maspin influences the transformation of epithelial cells and tumor behavior, the maspin-related processes are yet to be elucidated. Experimental studies are needed before chemical synthesis of a maspin-based agent can begin. Despite several unknown areas of the effects of maspin, several aspects have been confirmed by us and others. These aspects include: maspin is a good marker of budding quantification in colorectal carcinomas; it can be used for identification of intragastric mucosa signet ring cells (in biopsic specimens) or a proper evaluation of poorly cohesive gastric carcinoma invasion; and it is a useful marker for differential diagnosis of PanIN from a ductal adenocarcinoma of pancreas. The other aspects should be elucidated by further studies.

| 1. | Zou Z, Anisowicz A, Hendrix MJ, Thor A, Neveu M, Sheng S, Rafidi K, Seftor E, Sager R. Maspin, a serpin with tumor-suppressing activity in human mammary epithelial cells. Science. 1994;263:526-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 681] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sheng S, Carey J, Seftor EA, Dias L, Hendrix MJ, Sager R. Maspin acts at the cell membrane to inhibit invasion and motility of mammary and prostatic cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11669-11674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bodenstine TM, Seftor RE, Khalkhali-Ellis Z, Seftor EA, Pemberton PA, Hendrix MJ. Maspin: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:529-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Latha K, Zhang W, Cella N, Shi HY, Zhang M. Maspin mediates increased tumor cell apoptosis upon induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1737-1748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zou Z, Gao C, Nagaich AK, Connell T, Saito S, Moul JW, Seth P, Appella E, Srivastava S. p53 regulates the expression of the tumor suppressor gene maspin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6051-6054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang Y, Sun L, Song Z, Wang D, Bao Y, Li Y. Maspin inhibits macrophage phagocytosis and enhances inflammatory cytokine production via activation of NF-κB signaling. Mol Immunol. 2017;82:94-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dean I, Dzinic SH, Bernardo MM, Zou Y, Kimler V, Li X, Kaplun A, Granneman J, Mao G, Sheng S. The secretion and biological function of tumor suppressor maspin as an exosome cargo protein. Oncotarget. 2017;8:8043-8056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Berardi R, Morgese F, Onofri A, Mazzanti P, Pistelli M, Ballatore Z, Savini A, De Lisa M, Caramanti M, Rinaldi S, Pagliaretta S, Santoni M, Pierantoni C, Cascinu S. Role of maspin in cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2013;2:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dokras A, Gardner LM, Kirschmann DA, Seftor EA, Hendrix MJ. The tumour suppressor gene maspin is differentially regulated in cytotrophoblasts during human placental development. Placenta. 2002;23:274-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu Q, Qiao FY, Shi XW, Liu HY, Gong X, Wu YY. Promoter hypomethylation and increased maspin expression in preeclamptic placentas in a Chinese population. Placenta. 2014;35:876-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qi YH, Teng F, Zhou Q, Liu YX, Wu JF, Yu SS, Zhang X, Ma MY, Zhou N, Chen LJ. Unmethylated-maspin DNA in maternal plasma is associated with severe preeclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:983-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee DE, Kim SY, Lim JH, Park SY, Ryu HM. Non-invasive prenatal testing of trisomy 18 by an epigenetic marker in first trimester maternal plasma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shi X, Liu Q, Liu H, Deng D, Qiao F, Wu Y. Effects of shRNA Targeting Maspin on the Invasion of Extravillous Trophoblast Cell. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:966-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Taglauer ES, Gundogan F, Johnson KL, Scherjon SA, Bianchi DW. Chorionic plate expression patterns of the maspin tumor suppressor protein in preeclamptic and egg donor placentas. Placenta. 2013;34:385-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Umekita Y, Ohi Y, Sagara Y, Yoshida H. Expression of maspin predicts poor prognosis in breast-cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2002;100:452-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Umekita Y, Ohi Y, Souda M, Rai Y, Sagara Y, Sagara Y, Tamada S, Tanimoto A. Maspin expression is frequent and correlates with basal markers in triple-negative breast cancer. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee MJ, Suh CH, Li ZH. Clinicopathological significance of maspin expression in breast cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:309-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim DH, Yoon DS, Dooley WC, Nam ES, Ryu JW, Jung KC, Park HR, Sohn JH, Shin HS, Park YE. Association of maspin expression with the high histological grade and lymphocyte-rich stroma in early-stage breast cancer. Histopathology. 2003;42:37-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mohsin SK, Zhang M, Clark GM, Craig Allred D. Maspin expression in invasive breast cancer: association with other prognostic factors. J Pathol. 2003;199:432-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tamazato Longhi M, Magalhães M, Reina J, Morais Freitas V, Cella N. EGFR Signaling Regulates Maspin/SerpinB5 Phosphorylation and Nuclear Localization in Mammary Epithelial Cells. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gurzu S, Banias L, Bara T, Feher I, Bara T, Jung I. The Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Pathway in Two Cases with Gastric Metastasis Originating from Breast Carcinoma, One with a Metachronous Primary Gastric Cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2018;13:118-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Machowska M, Wachowicz K, Sopel M, Rzepecki R. Nuclear location of tumor suppressor protein maspin inhibits proliferation of breast cancer cells without affecting proliferation of normal epithelial cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Strien L, Joensuu K, Heikkilä P, Leidenius MH. Different Expression Patterns of CXCR4, CCR7, Maspin and FOXP3 in Luminal Breast Cancers and Their Sentinel Node Metastases. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:175-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wakahara M, Sakabe T, Kubouchi Y, Hosoya K, Hirooka Y, Yurugi Y, Nosaka K, Shiomi T, Nakamura H, Umekita Y. Subcellular Localization of Maspin Correlates with Histone Deacetylase 1 Expression in Human Breast Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:5071-5077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Umekita Y, Ohi Y, Iwaya O, Souda M, Sagara Y, Tamada S, Yotsumoto D, Tanimoto A. Maspin mRNA expression in sentinel lymph nodes predicts non-SLN metastasis in breast cancer patients with SLN metastasis. Histopathology. 2018;73:916-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Triulzi T, Ratti M, Tortoreto M, Ghirelli C, Aiello P, Regondi V, Di Modica M, Cominetti D, Carcangiu ML, Moliterni A, Balsari A, Casalini P, Tagliabue E. Maspin influences response to doxorubicin by changing the tumor microenvironment organization. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2789-2797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sood AK, Fletcher MS, Gruman LM, Coffin JE, Jabbari S, Khalkhali-Ellis Z, Arbour N, Seftor EA, Hendrix MJ. The paradoxical expression of maspin in ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2924-2932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bolat F, Gumurdulu D, Erkanli S, Kayaselcuk F, Zeren H, Ali Vardar M, Kuscu E. Maspin overexpression correlates with increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factors A, C, and D in human ovarian carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:379-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Abd El-Wahed MM. Expression and subcellular localization of maspin in human ovarian epithelial neoplasms: correlation with clinicopathologic features. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2005;17:173-183. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Surowiak P, Materna V, Drag-Zalesinska M, Wojnar A, Kaplenko I, Spaczyński M, Dietel M, Zabel M, Lage H. Maspin expression is characteristic for cisplatin-sensitive ovarian cancer cells and for ovarian cancer cases of longer survival rates. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25:131-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Xu C, Quddus MR, Sung CJ, Steinhoff MM, Zhang C, Lawrence WD. Maspin expression in CIN 3, microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma, and invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1102-1106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liu Z, Shi Y, Meng W, Liu Y, Yang K, Wu S, Peng Z. Expression and localization of maspin in cervical cancer and its role in tumor progression and lymphangiogenesis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:373-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yeom SY, Jang HL, Lee SJ, Kim E, Son HJ, Kim BG, Park C. Interaction of testisin with maspin and its impact on invasion and cell death resistance of cervical cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1469-1475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nosaka K, Horie Y, Shiomi T, Itamochi H, Oishi T, Shimada M, Sato S, Sakabe T, Harada T, Umekita Y. Cytoplasmic Maspin Expression Correlates with Poor Prognosis of Patients with Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Cervix. Yonago Acta Med. 2015;58:151-156. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Blandamura S, Alessandrini L, Saccardi C, Giacomelli L, Fabris A, Borghero A, Litta P. Maspin expression, subcellular localization and clinicopathological correlation in endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial adenocarcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2014;29:777-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Li HW, Leung SW, Chan CS, Yu MM, Wong YF. Expression of maspin in endometrioid adenocarcinoma of endometrium. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:393-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Tsuji T, Umekita Y, Ohi Y, Kamio M, Douchi T, Yoshida H. Maspin expression is up-regulated during the progression of endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. Histopathology. 2007;51:871-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Murai S, Maesawa C, Masuda T, Sugiyama T. Aberrant maspin expression in human endometrial cancer. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:883-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Machtens S, Serth J, Bokemeyer C, Bathke W, Minssen A, Kollmannsberger C, Hartmann J, Knüchel R, Kondo M, Jonas U, Kuczyk M. Expression of the p53 and Maspin protein in primary prostate cancer: correlation with clinical features. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:337-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Zou Z, Zhang W, Young D, Gleave MG, Rennie P, Connell T, Connelly R, Moul J, Srivastava S, Sesterhenn I. Maspin expression profile in human prostate cancer (CaP) and in vitro induction of Maspin expression by androgen ablation. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1172-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Pierson CR, McGowen R, Grignon D, Sakr W, Dey J, Sheng S. Maspin is up-regulated in premalignant prostate epithelia. Prostate. 2002;53:255-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Cheng WL, Huang CY, Tai CJ, Chang YJ, Hung CS. Maspin Enhances the Anticancer Activity of Curcumin in Hormone-refractory Prostate Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:863-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Dzinic SH, Chen K, Thakur A, Kaplun A, Bonfil RD, Li X, Liu J, Bernardo MM, Saliganan A, Back JB, Yano H, Schalk DL, Tomaszewski EN, Beydoun AS, Dyson G, Mujagic A, Krass D, Dean I, Mi QS, Heath E, Sakr W, Lum LG, Sheng S. Maspin expression in prostate tumor elicits host anti-tumor immunity. Oncotarget. 2014;5:11225-11236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Chen J, Wang L, Tang Y, Gong G, Liu L, Chen M, Chen Z, Cui Y, Li C, Cheng X, Qi L, Zu X. Maspin enhances cisplatin chemosensitivity in bladder cancer T24 and 5637 cells and correlates with prognosis of muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients receiving cisplatin based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zhu H, Yun F, Shi X, Wang D. Inhibition of IGFBP-2 improves the sensitivity of bladder cancer cells to cisplatin via upregulating the expression of maspin. Int J Mol Med. 2015;36:595-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zhu H, Yun F, Shi X, Wang D. VEGF-C inhibition reverses resistance of bladder cancer cells to cisplatin via upregulating maspin. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:3163-3169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Tsui KH, Lin YH, Chung LC, Chuang ST, Feng TH, Chiang KC, Chang PL, Yeh CJ, Juang HH. Prostate-derived ets factor represses tumorigenesis and modulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in bladder carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2016;375:142-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Lonardo F, Li X, Siddiq F, Singh R, Al-Abbadi M, Pass HI, Sheng S. Maspin nuclear localization is linked to favorable morphological features in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2006;51:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Matsuoka Y, Takagi Y, Nosaka K, Sakabe T, Haruki T, Araki K, Taniguchi Y, Shiomi T, Nakamura H, Umekita Y. Cytoplasmic expression of maspin predicts unfavourable prognosis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Histopathology. 2016;69:114-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Takagi Y, Matsuoka Y, Shiomi T, Nosaka K, Takeda C, Haruki T, Araki K, Taniguchi Y, Nakamura H, Umekita Y. Cytoplasmic maspin expression is a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with lung adenocarcinoma measuring < 3 cm. Histopathology. 2015;66:732-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Ohno T, Kubouchi Y, Wakahara M, Nosaka K, Sakabe T, Haruki T, Miwa K, Taniguchi Y, Nakamura H, Umekita Y. Clinical Significance of Subcellular Localization of Maspin in Patients with Pathological Stage IA Lung Adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:3001-3007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Lu M, Li J, Huang Z, Du Y, Jin S, Wang J. Aberrant Maspin mRNA Expression is Associated with Clinical Outcome in Patients with Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:134-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Meng H, Guan X, Guo H, Xiong G, Yang K, Wang K, Bai Y. Association between SNPs in Serpin gene family and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:6231-6238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Wang Y, Sheng S, Zhang J, Dzinic S, Li S, Fang F, Wu N, Zheng Q, Yang Y. Elevated maspin expression is associated with better overall survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). PLoS One. 2013;8:e63581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Cai Z, Zhou Y, Lei T, Chiu JF, He QY. Mammary serine protease inhibitor inhibits epithelial growth factor-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of esophageal carcinoma cells. Cancer. 2009;115:36-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Akiyama Y, Maesawa C, Ogasawara S, Terashima M, Masuda T. Cell-type-specific repression of the maspin gene is disrupted frequently by demethylation at the promoter region in gastric intestinal metaplasia and cancer cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1911-1919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Gurzu S, Jung I, Orlowska J, Sugimura H, Kadar Z, Turdean S, Bara T. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer--An overview. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211:629-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Gurzu S, Kadar Z, Sugimura H, Bara T, Bara T, Halmaciu I, Jung I. Gastric cancer in young vs old Romanian patients: immunoprofile with emphasis on maspin and mena protein reactivity. APMIS. 2015;123:223-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Gurzu S, Kadar Z, Sugimura H, Orlowska J, Bara T, Bara T, Szederjesi J, Jung I. Maspin-related Orchestration of Aggressiveness of Gastric Cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2016;24:326-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Zheng HC, Gong BC. The roles of maspin expression in gastric cancer: a meta- and bioinformatics analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:66476-66490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Wang MC, Yang YM, Li XH, Dong F, Li Y. Maspin expression and its clinicopathological significance in tumorigenesis and progression of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:634-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Gurzu S, Kadar Z, Bara T, Bara T, Tamasi A, Azamfirei L, Jung I. Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma of gastrointestinal tract: report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1329-1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Bettstetter M, Woenckhaus M, Wild PJ, Rümmele P, Blaszyk H, Hartmann A, Hofstädter F, Dietmaier W. Elevated nuclear maspin expression is associated with microsatellite instability and high tumour grade in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 2005;205:606-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Kim JH, Cho NY, Bae JM, Kim KJ, Rhee YY, Lee HS, Kang GH. Nuclear maspin expression correlates with the CpG island methylator phenotype and tumor aggressiveness in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:1920-1928. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Baek JY, Yeo HY, Chang HJ, Kim KH, Kim SY, Park JW, Park SC, Choi HS, Kim DY, Oh JH. Serpin B5 is a CEA-interacting biomarker for colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1595-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Chang IW, Liu KW, Ragunanan M, He HL, Shiue YL, Yu SC. SERPINB5 Expression: Association with CCRT Response and Prognostic Value in Rectal Cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2018;15:376-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Hestetun KE, Brydøy M, Myklebust MP, Dahl O. Nuclear maspin expression as a predictive marker for fluorouracil treatment response in colon cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:470-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Dietmaier W, Bettstetter M, Wild PJ, Woenckhaus M, Rümmele P, Hartmann A, Dechant S, Blaszyk H, Pauer A, Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Hofstädter F. Nuclear Maspin expression is associated with response to adjuvant 5-fluorouracil based chemotherapy in patients with stage III colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2247-2254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Findeisen P, Röckel M, Nees M, Röder C, Kienle P, Von Knebel Doeberitz M, Kalthoff H, Neumaier M. Systematic identification and validation of candidate genes for detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood specimens of colorectal cancer patients. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:1001-1010. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Uzozie AC, Selevsek N, Wahlander A, Nanni P, Grossmann J, Weber A, Buffoli F, Marra G. Targeted Proteomics for Multiplexed Verification of Markers of Colorectal Tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2017;16:407-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Gurzu S, Szentirmay Z, Jung I. Molecular classification of colorectal cancer: a dream that can become a reality. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2013;54:241-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Gurzu S, Szentirmay Z, Popa D, Jung I. Practical value of the new system for Maspin assessment, in colorectal cancer. Neoplasma. 2013;60:373-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Banias L, Gurzu S, Kovacs Z, Bara T, Bara T, Jung I. Nuclear maspin expression: A biomarker for budding assessment in colorectal cancer specimens. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213:1227-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Gurzu S, Szentirmay Z, Toth E, Jung I. Possible predictive value of maspin expression in colorectal cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2013;8:183-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Chen WS, Liu LC, Yen CJ, Chen YJ, Chen JY, Ho CY, Liu SH, Chen CC, Huang WC. Nuclear IKKα mediates microRNA-7/-103/107/21 inductions to downregulate maspin expression in response to HBx overexpression. Oncotarget. 2016;7:56309-56323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Wei X, Li J, Xie H, Wang H, Wang J, Zhang X, Zhuang R, Lu D, Ling Q, Zhou L, Xu X, Zheng S. Chloride intracellular channel 1 participates in migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting maspin. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:208-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Yang SF, Yeh CB, Chou YE, Lee HL, Liu YF. Serpin peptidase inhibitor (SERPINB5) haplotypes are associated with susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Romani AA, Soliani P, Desenzani S, Borghetti AF, Crafa P. The associated expression of Maspin and Bax proteins as a potential prognostic factor in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Furuhata A, Minamiguchi S, Shirahase H, Kodama Y, Adachi S, Sakurai T, Haga H. Immunohistochemical Antibody Panel for the Differential Diagnosis of Pancreatic Ductal Carcinoma From Gastrointestinal Contamination and Benign Pancreatic Duct Epithelium in Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration. Pancreas. 2017;46:531-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Nitta T, Mitsuhashi T, Hatanaka Y, Hirano S, Matsuno Y. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas with multiple large cystic structures: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of seven cases. Pancreatology. 2013;13:401-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Ohike N, Maass N, Mundhenke C, Biallek M, Zhang M, Jonat W, Lüttges J, Morohoshi T, Klöppel G, Nagasaki K. Clinicopathological significance and molecular regulation of maspin expression in ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer Lett. 2003;199:193-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Gurzu S, Bara T, Molnar C, Bara T, Butiurca V, Beres H, Savoji S, Jung I. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition induces aggressivity of mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas with neuroendocrine component: An immunohistochemistry study. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215:82-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Mardin WA, Ntalos D, Mees ST, Spieker T, Senninger N, Haier J, Dhayat SA. SERPINB5 Promoter Hypomethylation Differentiates Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma From Pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2016;45:743-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Klett H, Fuellgraf H, Levit-Zerdoun E, Hussung S, Kowar S, Küsters S, Bronsert P, Werner M, Wittel U, Fritsch R, Busch H, Boerries M. Identification and Validation of a Diagnostic and Prognostic Multi-Gene Biomarker Panel for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Front Genet. 2018;9:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Mao Y, Shen J, Lu Y, Lin K, Wang H, Li Y, Chang P, Walker MG, Li D. RNA sequencing analyses reveal novel differentially expressed genes and pathways in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:42537-42547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Kanzawa M, Sanuki T, Onodera M, Fujikura K, Itoh T, Zen Y. Double immunostaining for maspin and p53 on cell blocks increases the diagnostic value of biliary brushing cytology. Pathol Int. 2017;67:91-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Baghel K, Kazmi HR, Raj S, Chandra A, Srivastava RN. Elevated expression of maspin mRNA as a predictor of survival in stage II and III gallbladder cancer cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:343-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Shi J, Liu H, Wang HL, Prichard JW, Lin F. Diagnostic utility of von Hippel-Lindau gene product, maspin, IMP3, and S100P in adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:503-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Chen L, Huang K, Himmelfarb EA, Zhai J, Lai JP, Lin F, Wang HL. Diagnostic value of maspin in distinguishing adenocarcinoma from benign biliary epithelium on endoscopic bile duct biopsy. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:1647-1654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Tokumitsu T, Sato Y, Yamashita A, Moriguchi-Goto S, Kondo K, Nanashima A, Asada Y. Immunocytochemistry for Claudin-18 and Maspin in biliary brushing cytology increases the accuracy of diagnosing pancreatobiliary malignancies. Cytopathology. 2017;28:116-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Keira Y, Takasawa A, Murata M, Nojima M, Takasawa K, Ogino J, Higashiura Y, Sasaki A, Kimura Y, Mizuguchi T, Tanaka S, Hirata K, Sawada N, Hasegawa T. An immunohistochemical marker panel including claudin-18, maspin, and p53 improves diagnostic accuracy of bile duct neoplasms in surgical and presurgical biopsy specimens. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:265-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Ma S, Pang C, Song L, Guo F, Sun H. Activating transcription factor 3 is overexpressed in human glioma and its knockdown in glioblastoma cells causes growth inhibition both in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Med. 2015;35:1561-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Xu L, Liu H, Yu J, Wang Z, Zhu Q, Li Z, Zhong Q, Zhang S, Qu M, Lan Q. Methylation-induced silencing of maspin contributes to the proliferation of human glioma cells. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Safadi RA, Quda BF, Hammad HM. Immunohistochemical expression of K6, K8, K16, K17, K19, maspin, syndecan-1 (CD138), α-SMA, and Ki-67 in ameloblastoma and ameloblastic carcinoma: diagnostic and prognostic correlations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;121:402-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Yang PY, Miao NF, Lin CW, Chou YE, Yang SF, Huang HC, Chang HJ, Tsai HT. Impact of Maspin Polymorphism rs2289520 G/C and Its Interaction with Gene to Gene, Alcohol Consumption Increase Susceptibility to Oral Cancer Occurrence. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Tsai HT, Hsieh MJ, Lin CW, Su SC, Miao NF, Yang SF, Huang HC, Lai FC, Liu YF. Combinations of SERPINB5 gene polymorphisms and environmental factors are associated with oral cancer risks. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0163369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Xia W, Lau YK, Hu MC, Li L, Johnston DA, Sheng Sj, El-Naggar A, Hung MC. High tumoral maspin expression is associated with improved survival of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2000;19:2398-2403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Yasumatsu R, Nakashima T, Hirakawa N, Kumamoto Y, Kuratomi Y, Tomita K, Komiyama S. Maspin expression in stage I and II oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2001;23:962-966. [PubMed] |

| 99. | Choi KY, Choi HJ, Chung EJ, Lee DJ, Kim JH, Rho YS. Loss of heterozygosity in mammary serine protease inhibitor (maspin) and p53 at chromosome 17 and 18 in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2015;37:1239-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Marioni G, Zanoletti E, Stritoni P, Lionello M, Giacomelli L, Gianatti A, Cattaneo L, Blandamura S, Mazzoni A, Martini A. Expression of the tumour-suppressor maspin in temporal bone carcinoma. Histopathology. 2013;63:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Marioni G, Blandamura S, Giacomelli L, Calgaro N, Segato P, Leo G, Fischetto D, Staffieri A, de Filippis C. Nuclear expression of maspin is associated with a lower recurrence rate and a longer disease-free interval after surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Histopathology. 2005;46:576-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Reshma V, Rao K, Priya NS, Umadevi HS, Smitha T, Sheethal HS. Expression of maspin in benign and malignant salivary gland tumors: an immunohistochemical study. Indian J Dent Res. 2014;25:346-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Tarakji B, Ashok N, Sheirawan MK, Altamimi MA, Alenzi F, Azzeghaiby SN, Baroudi K, Nassani MZ. Maspin as a tumour suppressor in salivary gland tumour. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZE05-ZE07. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Huang YD, Yu HW, Xia SW, Kang ZH, He YS, Han DY. Expression of maspin in invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. J Laryngol Otol. 2017;131:150-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Ngamkitidechakul C, Burke JM, O'Brien WJ, Twining SS. Maspin: synthesis by human cornea and regulation of in vitro stromal cell adhesion to extracellular matrix. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:3135-3141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Stephen JK, Chen KM, Merritt J, Chitale D, Divine G, Worsham MJ. Methylation markers differentiate thyroid cancer from benign nodules. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;41:163-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Boltze C, Schneider-Stock R, Quednow C, Hinze R, Mawrin C, Hribaschek A, Roessner A, Hoang-Vu C. Silencing of the maspin gene by promoter hypermethylation in thyroid cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2003;12:479-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Ciortea CD, Jung I, Gurzu S, Kövecsi A, Turdean SG, Bara T. Correlation of angiogenesis with other immunohistochemical markers in cutaneous basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:665-670. [PubMed] |

| 109. | Zhu H, Mao Q, Liu W, Yang Z, Jian X, Qu L, He C. Maspin suppresses growth, proliferation and invasion in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:2875-2882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Reis-Filho JS, Torio B, Albergaria A, Schmitt FC. Maspin expression in normal skin and usual cutaneous carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2002;441:551-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Turdean SG, Gurzu S, Jung I, Neagoe RM, Sala D. Unexpected maspin immunoreactivity in Merkel cell carcinoma. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Martinoli C, Gandini S, Luise C, Mazzarol G, Confalonieri S, Giuseppe Pelicci P, Testori A, Ferrucci PF. Maspin expression and melanoma progression: a matter of sub-cellular localization. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:412-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Pföhler C, Knöpflen T, Körner R, Vogt T, Rösch A, Müller CS. Maspin expression in the invasive margin of primary melanomas may reflect an aggressive tumor phenotype. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:993-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Gurzu S, Turdean SG, Pop ST, Zazgyva A, Roman CO, Opris M, Jung I. Different synovial vasculogenic profiles of primary, rapidly destructive and osteonecrosis-induced hip osteoarthritis. An immunohistochemistry study. Int Orthop. 2017;41:1107-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Takeda C, Takagi Y, Shiomi T, Nosaka K, Yamashita H, Osaki M, Endo K, Minamizaki T, Teshima R, Nagashima H, Umekita Y. Cytoplasmic maspin expression predicts poor prognosis of patients with soft tissue sarcomas. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 116. | Jung I, Gurzu S, Turdean S, Ciortea D, Sahlean DI, Golea M, Bara T. Relationship of endothelial area with VEGF-A, COX-2, maspin, c-KIT, and DOG-1 immunoreactivity in liposarcomas versus non-lipomatous soft tissue tumors. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:1776-1782. [PubMed] |

| 117. | Gurzu S, Ciortea D, Tamasi A, Golea M, Bodi A, Sahlean DI, Kovecsi A, Jung I. The immunohistochemical profile of granular cell (Abrikossoff) tumor suggests an endomesenchymal origin. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307:151-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Bara T, Jung I, Gurzu S, Kádár Z, Kövecsi A, Bara T. Giant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach: a challenging diagnostic and therapeutically approach. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:1503-1506. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Romania

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: El Ghoch M S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Wu YXJ