Published online Mar 31, 2019. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v7.i3.110

Peer-review started: February 22, 2019

First decision: March 5, 2019

Revised: March 21, 2019

Accepted: March 24, 2019

Article in press: March 25, 2019

Published online: March 31, 2019

Processing time: 37 Days and 10.5 Hours

Antifoaming agents, such as simethicone, may facilitate mucosal inspection during colonoscopy. However, conflicting results have been reported with regard to the impact of simethicone on quality of bowel preparation and adenoma detection rate (ADR).

To perform a meta-analysis of trials that have compared simethicone vs placebo during colonoscopy.

A reproducible literature search of multiple medical databases yielded eleven studies (n = 2605) for inclusion. Studies were compared for quality of bowel preparation, bubbles quality, ADR, and tolerability. Two reviewers independently scored the identified studies for methodology and abstracted pertinent data. Pooling was conducted by both fixed-effects and random-effects models. Relative risk (RR) estimates with a 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. Heterogeneity was assessed by I-squared index (I2) statistics.

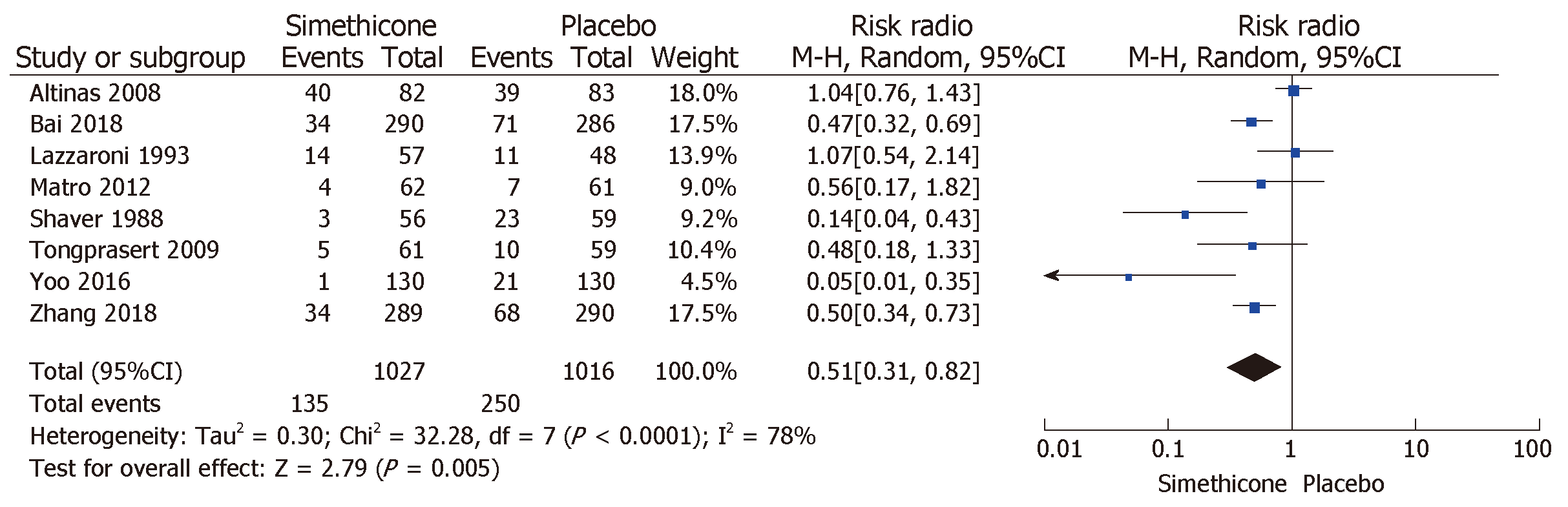

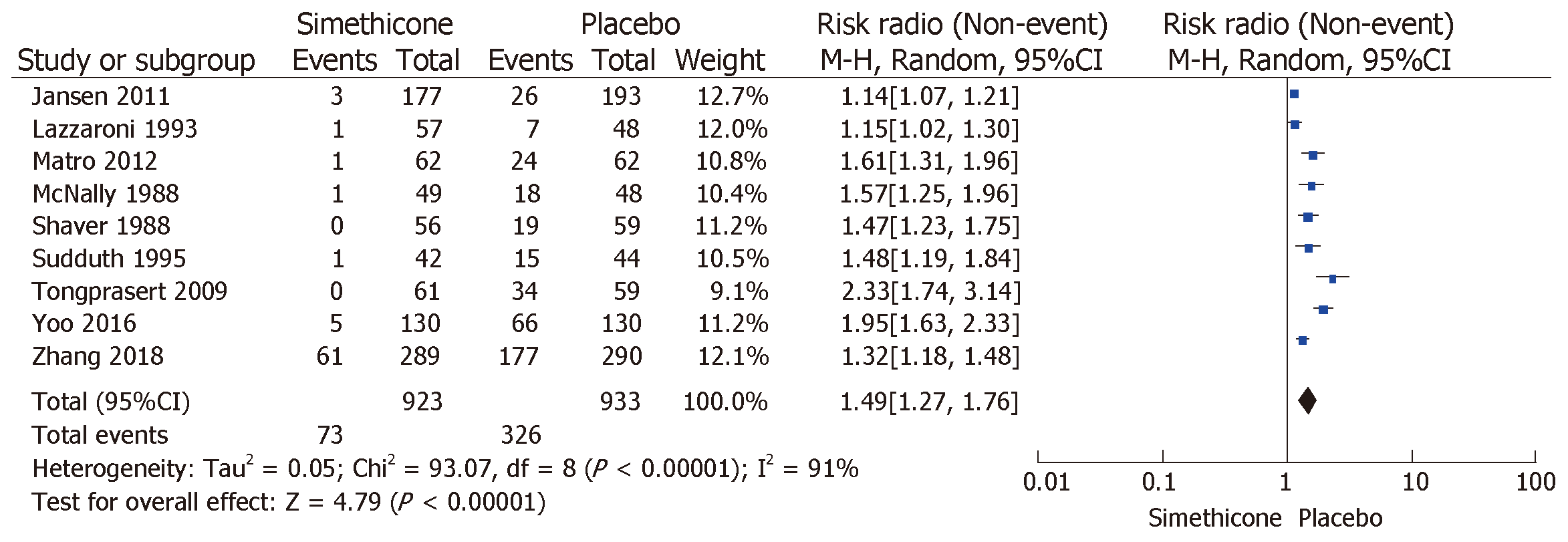

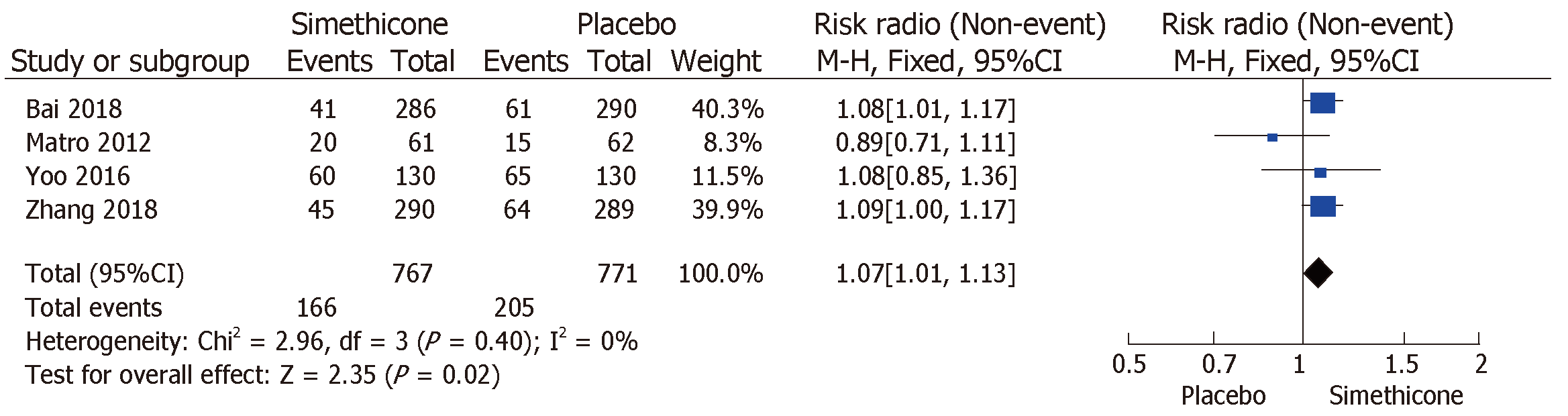

Patients’ demographic characteristics were comparable in all studies. Of the 2605 patients, 1300 were in the simethicone group, whereas 1305 were in the placebo group. Inadequate bowel preparation was much lower in the simethicone group than in the placebo group [13% vs 24.6%; RR = 0.51 (0.31-0.82); P < 0.0001]. The placebo group was more likely to have significant colonic bubbles than was the simethicone group [35% vs 8%; RR = 1.49 (1.25-1.76); P = 0.0001]. Use of simethicone resulted in a slight, statistically significant increase in ADR compared with the placebo group [26.6% vs 21.6%, RR = 1.07 (1.01-1.13); P = 0.02]. Higher doses of simethicone (> 478 mg) were more likely to result in significant reduction of inadequate bowel preparation, colonic bubbles, and to improve ADR.

Adding simethicone improved the quality of bowel preparation, visualization, tolerability, and, eventually, ADR.

Core tip: Colonoscopy is an essential tool in the screening for and preventing colon cancer, but inadequate colon preparation limits visualization, prolongs procedure time, and, affects exam quality. An antifoaming agent, simethicone, has been a promising addition to bowel preparation. This meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials assessed the effect of its addition to commonly utilized bowel preparations and analyzed the optimum effective dose. We concluded that the addition of simethicone to bowel preparation significantly reduced inadequate bowel preparation, increased adenoma detection rate and trended to improved tolerability of the prep. Higher doses of simethicone were more likely to achieve those outcomes.

- Citation: Madhoun MF, Hayat M, Ali IA. Higher dose of simethicone decreases colonic bubbles and increases prep tolerance and quality of bowel prep: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Meta-Anal 2019; 7(3): 110-119

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v7/i3/110.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v7.i3.110

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading type of cancer worldwide, with 1-2 million new cases every year and a mortality rate of 600000/year[1]. Colonoscopy is an important tool for CRC screening and surveillance[2]. The presence of fecal residue and bubbles during the exam may limit visualization, prolong the procedure time, and, hence, affect the quality of the exam[3]. An antifoaming agent, simethicone, has been a promising addition to bowel preparation. It reduces the surface tension of air bubbles and has been shown to reduce bloating and abdominal pain, as well as improve mucosal visualization[4]. Results regarding improvement in the quality of bowel preparation and adenoma detection rate (ADR), however, have been mixed[4]. The aim of this study was to encompass recent randomized controlled trials in a meta-analysis to assess the effect of simethicone on bowel preparation, ADR, and patient compliance and to assess the optimal dose of simethicone to achieve aforementioned effects.

The methods of our analysis and inclusion criteria were based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations.

One investigator (MM) and a research librarian independently designed and conducted a computer-assisted scan of multiple medical literature databases (including PubMed and OVID EMBASE) for relevant papers published from the start of 1947 through October 2018. A reproducible systematic literature search strategy was employed that searched for the term: “colonoscopy” AND “simethicone” OR “anti-foaming agent”. Two investigators (MM, HM) examined all published studies that compared simethicone with placebo in the improvement of bowel preparation, bubbles quality, ADR, and tolerability.

Investigators were not blinded to journal titles, author names, or institutional affiliations. Both inclusion and exclusion criteria were drafted before the initiation of literature review. Titles and abstracts were screened initially for potentially relevant studies. Once these articles were listed, the studies that clearly did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded. Later, full manuscripts were studied in detail to ensure that the selected studies were appropriate for our analysis. Any disagreement was resolved by the senior investigator.

For a trial of simethicone compared with placebo to qualify for inclusion in this meta-analysis, it should have met the following criteria: (1) prospective randomized controlled trial; (2) comparison of simethicone with placebo; and (3) either bowel preparation quality, bubbles score, ADR, or a combination of any of these parameters was studied.

One author (MM) extracted data from studies in tabulated data extraction forms and validated by a second author (MH). Extracted data was compared to the original research papers. The following data were collected: first author, publication year, country of origin, multi-center participation, number of subjects in each group, trainees’ involvement, sedation, pre-procedure diet, split dosing, blinding, patient demographics, indications of colonoscopy, quality and method used to assess bowel preparation, scoring of bubbles in lumen, ADR, polyp detection rate, and side effects and tolerance of prep material. Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved by consensus.

Rate of inadequate bowel preparation was the primary outcome. The definition of inadequate bowel preparation was either based on Boston Bowel Preparation score [(BBPS) < 6] or subjective reporting of “fair” or “poor” or “inadequate” in the included studies. Secondary outcomes included significant presence of colonic bubbles (more than minimal bubbles), ADR, and tolerability of bowel preparation, including bloating, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

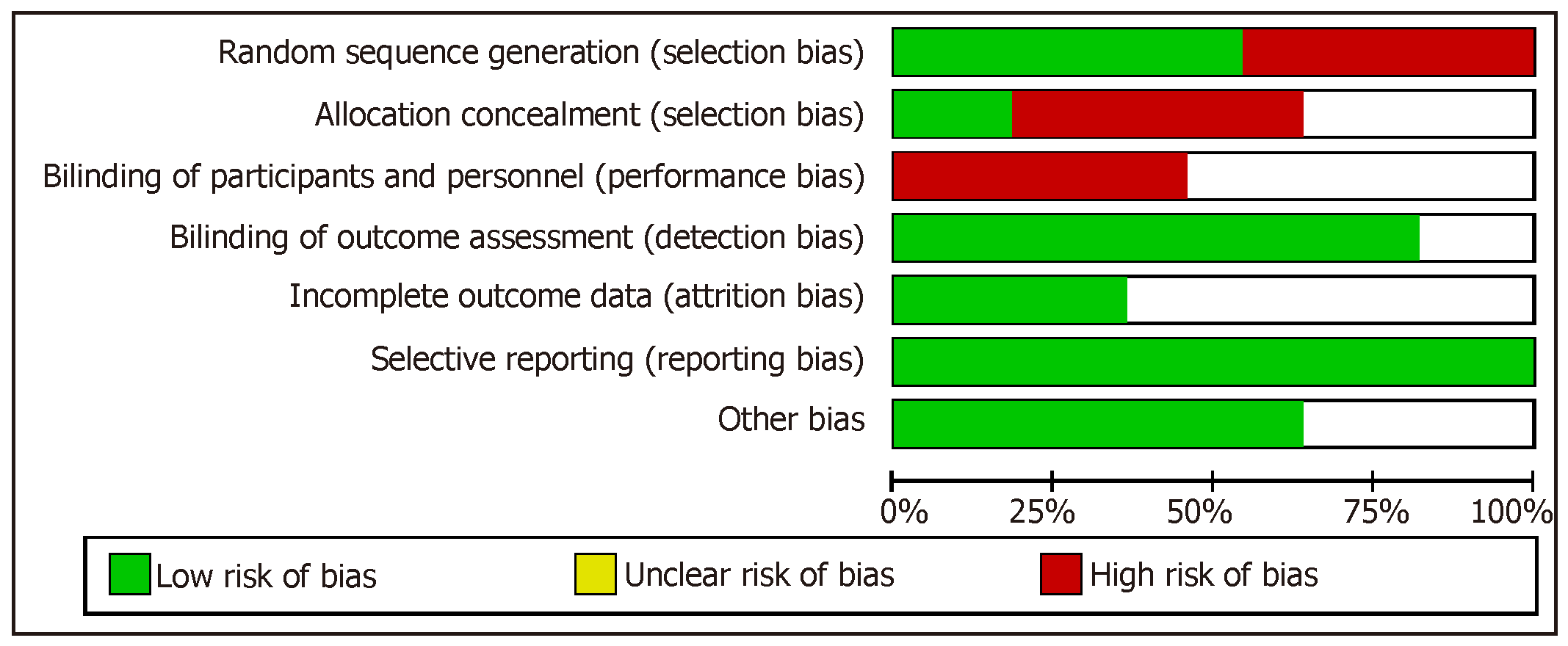

Bias was assessed by utilizing the Cochrane Collaboration Risk tool which is available in Review Manager 5. There are six criteria which this tool uses to evaluate four bias sources. To assess selection bias, it evaluates adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment. To assess detection and performance bias, it checks whether blinding is effective with respect to personnel, participant, and outcome assessors. To assess attrition bias, it assesses completeness of outcome data. To assess reporting bias, it assesses if selective reporting is present. It also has a protocol to assess other biases such as early withdrawal or extreme baseline imbalances. If a trial excelled in the aforementioned domains it was categorized to lowest risk of bias. If any disagreements occurred among the extracting authors, they were solved by consensus.

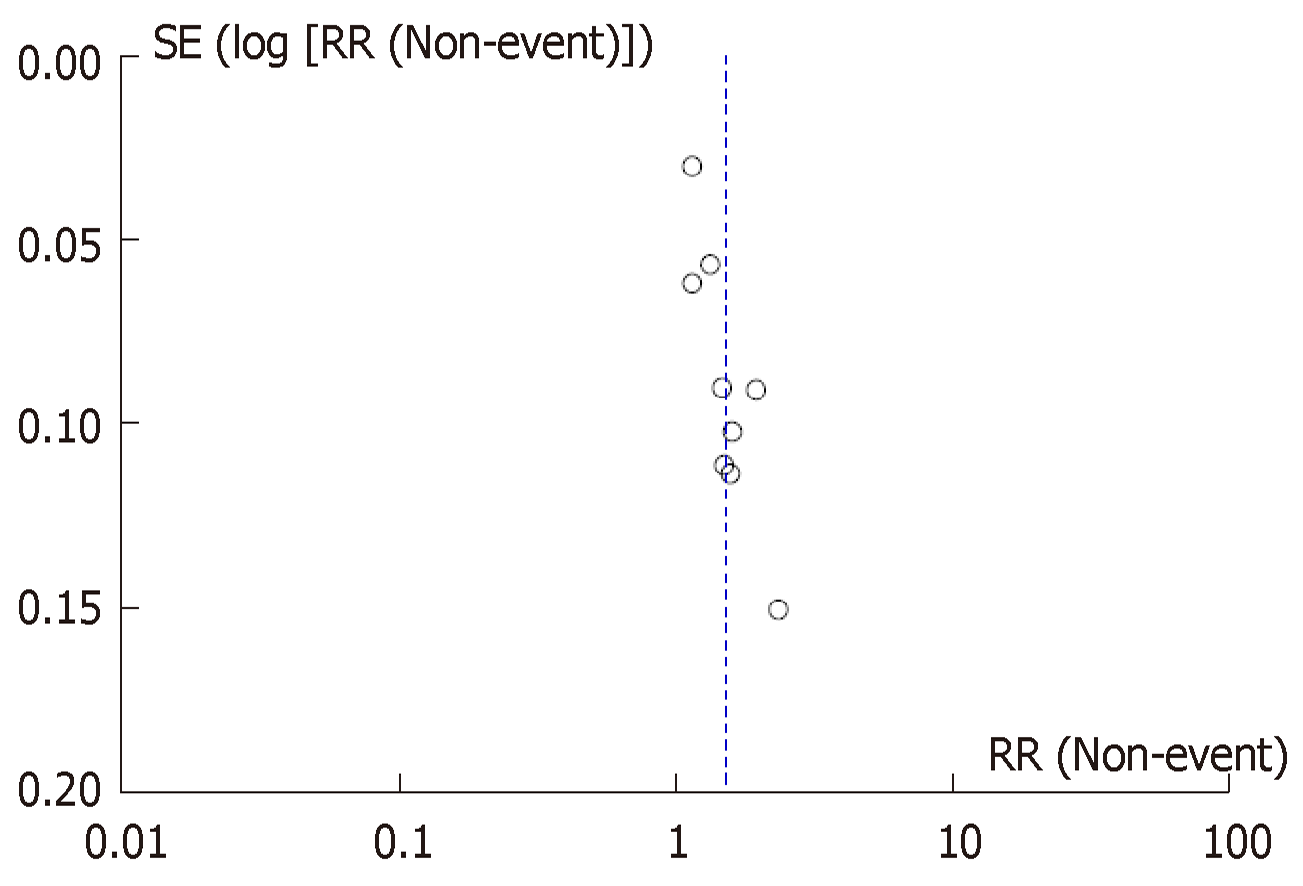

The software utilized to conduct this meta-analysis is Review Manager (RevMan) v5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, the Cochrane Collaboration). Assessments were made under Mantel-Haenszel fixed-effects method with summary risk ratio and 95% confidence interval. Random-effects model was used to combine estimates. If no significant heterogeneity (P > 0.1) was noted, fixed-effects model was rendered. Statistical tests were 2-sided and P < 0.05 was considered significant. Effort was made to report 95%CIs with the pooled data. A funnel plot was utilized to evaluate publication bias (inverse standard error for each study was plotted against natural log of the RR (InRR). Heterogeneity was assessed by I2 statistics, with value of more than 40% reported as substantial heterogeneity.

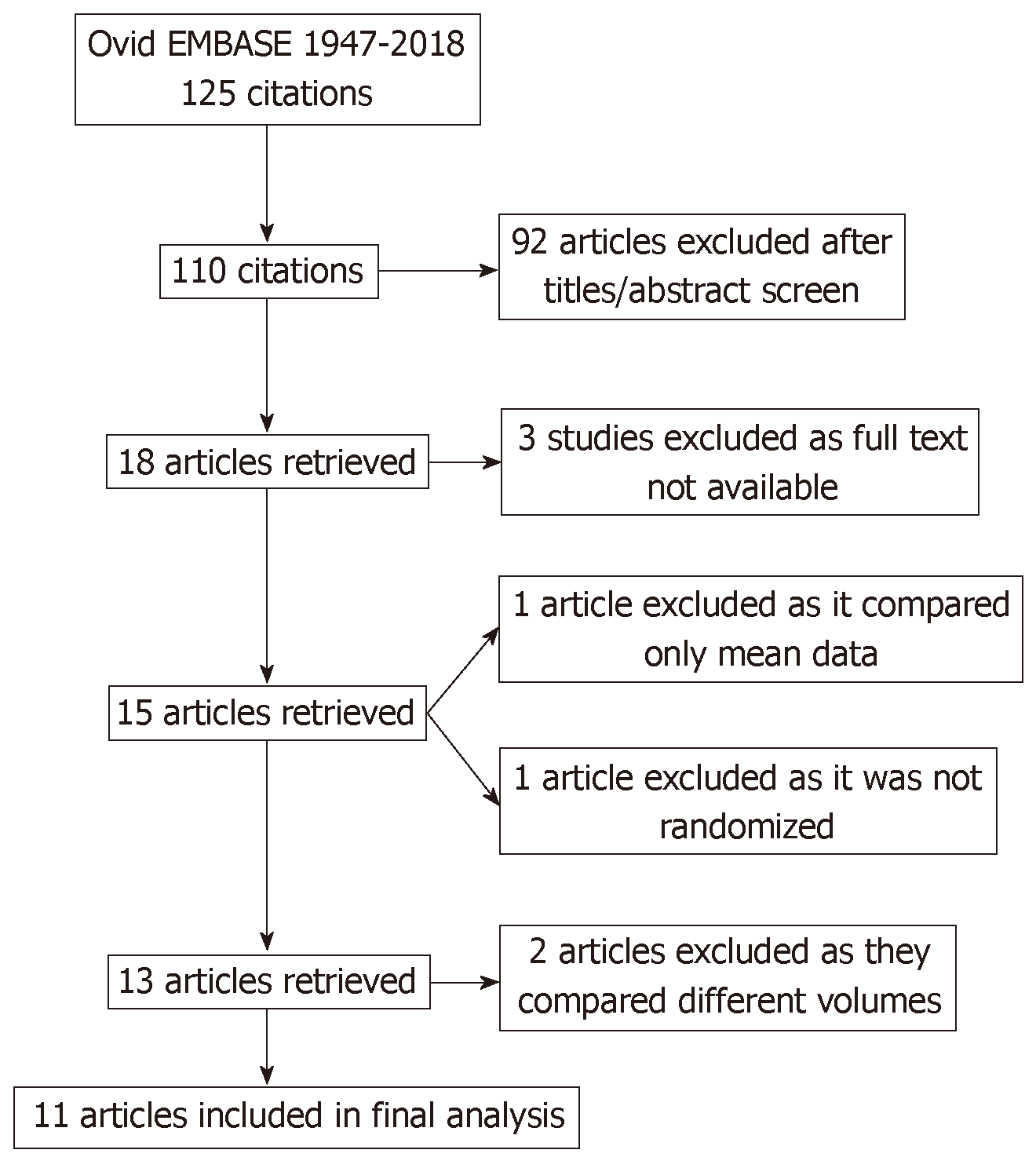

The literature search yielded eighteen potential studies for inclusion. Full text was only available for fifteen studies. Two studies were immediately excluded after initial review, because they compared different volumes in the experimental and control arms[5,6]. Two studies examined simethicone vs placebo, but were not included in this meta-analysis; one study included only mean data[7], and the other was a prospective, but not randomized, clinical trial[8]. Eleven studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). On manual review of the references of retrieved manuscripts, no other studies meeting inclusion criteria were identified.

There were four studies from Asia[9-12], two from Europe[13,14], and five from North America (Table 1)[15-19]. All studies provided some sort of patient demographic information. Five studies provided data regarding sex distribution and there was no difference in male/female distribution across arms (P = 0.91)[9-12,15]. Four studies provided data regarding age distribution which was not different either (P = 0.85)[9-12]. The number of participants in these studies ranged from 42 to 294. One study involved only patients with inflammatory bowel disease[13]. Symptomatic indication was the highest reason for colonoscopy (67%) among the five studies with detailed information regarding indication[9-12,15]. All studies but two commented on the quality of bowel preparation[17,19]. Three studies used the Boston Bowel Preparation Score (BBPS)[9-11]; adequate preparation was defined as total score of ≥ 6. Three studies used a subjective tool (excellent-good-fair-poor)[12,13,15]; adequate preparation was defined as scores of “excellent” or “good”. One study used a dichotomous subjective tool (good or poor)[18], with adequate preparation defined as a score of “good”. One study used a 0 to 4 scoring system, where 0 represented hard stool and 4 represented no stool; a score of 3 or 4 was considered adequate[14]. All studies but two examined the degree of air bubbles[14,18]. The degree of air bubbles was summarized as significant (no or minimal bubbles) vs not significant (more than minimal bubbles) to accommodate the various definitions used in these trials. Only two studies assessed the relationship of simethicone use to ADR[9,10].

| Ref. | Country | No. of patientsSimethicone/placebo | Bowel preparation used | Simethicone | Timing of Simethicone | Timing of bowel preparation | Diet prior to colonoscopy |

| McNally et al[19] | United States | 49/48 | 6L PEG | 160 mg | Mixed with PEG | Not clear | NA |

| Shaver et al[18] | United States | 102/102 | 5L PEG | 75 mL (30% simethicone) | 45 mL before and 30 mL after ingestion of PEG | Night before | NA |

| Lazzaroni et al[13] | Italy | 57/48 | 4L PEG | 120 mg | Mixed with PEG | Split dose | NA |

| Sudduth et al[17] | United States | 42/44 | 45 mL NaP × 2 doses | 320 mg | 160 mg after each dose of 45 mL NaP | Split dose | Clear liquid the day before |

| Altintas et al[14] | Turkey | 82/83 | 90 mL NaP/133 mL NaP | 300 mg | Capsule containing simethicone given 3 times/d × 5 d | Split dose | Watery or low fiber diet × 5 d |

| Tongprasert et al[12] | Thailand | 62/60 | 45 mL NaP × 2 doses | 480 mg | 240 mg with each 45 mL NaP | NA | Low residue the day before |

| Jansen et al[16] | United States | 177/193 | 4L PEG/PEG-Asc | 200 mg (20 mL 10 mg/mL) | 20 mL with the last L of PEG | Split dose | NA |

| Matro et al[15] | United States | 62/61 | PEG-Asc | 400 mg | Added to PEG | Split dose | Low residue for breakfast (the day before), followed by clear liquid |

| Yoo et al[11] | South Korea | 130/130 | PEG-Asc | 400 mg | Added to the last 500 mL of clear fluid | Split dose | Low residue × 3 days/clear liquid the night before |

| Zhang et al[9] | China | 289/290 | 2L PEG | 1200 mg | Added to PEG | Day of procedure | Low residue the day before |

| Bai et al[10] | China | 294/289 | 2L PEG | 1200 mg (30 mL, 40 mg/mL) | Added to PEG | Day of procedure | Low residue/clear liquid the night before |

Three studies used a 2-l PEG solution with ascorbic acid, Moviprep (Norgine, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), in a split dose fashion[11,15,16]. Two studies used a 2-l PEG solution only on the morning of procedure[9,10]. Three studies used sodium phosphate solution (Nap)[12,14,17]. Two studies used 4-l PEG solution[13,18]. One study used 5-l PEG[18], and another used 6-l PEG[19]. Among the various studies, the dose of simethicone ranged from 120 mg to 900 mg daily for five days.

When assessing domains in risk of bias, we noted that all trials had inadequate bias control (Figure 2). The principle risks of bias noted were allocation concealment and participant blinding.

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria (n = 2605). Of the 2605 patients, 1300 were in the simethicone group, whereas 1305 were in the placebo group. Given that the between-study variability was substantially high for the pooled RR of inadequate bowel preparation, significant colonic bubbles, abdominal pain and distension, the random effects model was employed Since the I2 of the pooled RR of the ADR, nausea, and vomiting was less than 40%, the fixed effects model was utilized for these analyses.

The rate of inadequate bowel preparation was much lower in the simethicone group than in the placebo group [13% vs 24.6%; RR = 0.51 (0.31-0.82); P < 0.0001; Figure 3]. The placebo group was more likely to have significant colonic bubbles than was the simethicone group [34.9% vs 8%; RR = 1.49 (1.25-1.76); P = 0.0001; Figure 4]. Use of simethicone resulted in a slight, statistically significant increase in ADR compared with the placebo group [26.6% vs 21.6%, RR = 1.07 (1.01-1.13); P = 0.02; Figure 5].

With regards to tolerability, simethicone use resulted in less abdominal distension [16.6% vs 30%, RR = 0.58 (0.43-0.78); P = 0.0003] and trends towards less abdominal pain [8.1% vs 12.3%, RR = 0.66 (0.42-1.03); P = 0.07]. There was no difference between the two groups with regard to nausea [23.6% vs 22.8%, RR = 1.02 (0.86-1.21); P = 0.78] or vomiting [8.4% vs 8.4%, RR = 0.99 (0.71-1.38); P = 0.97].

With regards to simethicone dose, the mean dose was calculated to be 478mg. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to compare inadequate bowel preparation, significant bubbles and ADR among PEG based, NaP based bowel preparations and simethicone dose above and below the mean dose (478 mg). Although both dose categories resulted in significant reduction in colonic bubbles, higher than mean dose of simethicone were significantly associated with adequate bowel preparation and ADR (Table 2). No significant publication bias was noted when inadequate bowel preparation outcome was analyzed via funnel plot (Figure 6).

| PEG purgatives | NaP purgatives | Simethicone dose above the mean (478 mg) | Simethicone dose below the mean(478 mg) | |

| Inadequate bowel preparation | 0.44 (0.26-0.73), P = 0.002, n = 6 | 0.82 (0.41-1.67), P = 0.59, n = 2 | 0.61 (0.38-0.98), P = 0.04, n = 4 | 0.29 (0.07-1.18), P = 0.08, n = 4 |

| Significant bubbles | 1.42 (1.2-1.7), P < 0.0001, n = 7 | 1.84 (1.1-2.9), P = 0.01, n = 2 | 1.79 (1.26-2.53), P = 0.001, n = 3 | 1.37 (1.17-1.59), P < 0.0001, n = 6 |

| ADR | NA | NA | 1.08 (1.03-1.15), P = 0.003, n = 2 | 1.0 (0.85-1.19), P = 0.98, n = 2 |

Simethicone is polydimethylsiloxane mixture that is frequently prescribed to reduce abdominal discomfort from excessive gas in the bowel. This anti-foaming agent reduces the surface tension of air bubbles so they merge and are easily passed via belching or flatulence.

In this meta-analysis, simethicone use resulted in a 50% reduction in inadequate bowel preparation and an almost 50% improvement in colonic bubbles during colonoscopy. Improvement in bowel preparation quality is likely attributed to reduced foam formation and reduced possibility of residual stool adherence to the colon, enhancing its expulsion from the gastrointestinal tract[10]. In the trials included, there were significant disparities in simethicone dose (120 to 1200 mg), mode of administration (mostly, mixed with the purgative solution), and timing of administration (depending on the timing of purgative used; mostly, split dosing was utilized).

Two earlier meta-analyses related to simethicone and colonoscopy quality were published[20,21]. Wu et al[20] noted no improvement in the quality of bowel preparation when using simethicone in addition to regular purgatives. However, of the 13 studies included in that meta-analysis, seven evaluated colonoscopies specifically, and all had relatively small sample sizes (18-82 patients in each arm) and significant variability in bowel preparation utilized. Recently, Pan et al[21] examined the impact of simethicone use on ADRs in 1855 patients undergoing colonoscopies. This meta-analysis was restricted to trials that used PEG as the bowel purgative. Two of the six trials included in the meta-analysis used different PEG volumes in the placebo and control arms.

Our meta-analysis results concur with those of Pan et al[21] with regard to significant improvement of ADR. However, we included only RCTs that used the same volume and type of purgatives in each arm, regardless of whether the purgative was PEG-based. We included non-PEG-based alternatives as well, which confirms the broad applicability of simethicone. We also examined other outcomes, including quality of bowel preparation, significant bubbles, and tolerability. Additionally, we performed multiple sensitivity analyses to evaluate the impact of simethicone on quality of bowel preparation, colonic bubbles, and ADR relative to the type of purgative or the dose of simethicone. We found that the beneficial effect of simethicone on the improvement of the quality of bowel preparation was more pronounced with PEG-based purgatives than with purgatives based on sodium phosphate. We also found that simethicone doses above the mean (478 mg) were more likely to result in significant reduction of inadequate bowel preparation, colonic bubbles, and ADR (Table 2). We feel this highlights an important area of research, as studies evaluating optimal dose of simethicone are lacking.

Simethicone is a well-tolerated and safe drug. It has very few side effects, given that the drug is not absorbed into the blood stream[22]. In our meta-analysis, we found that simethicone improved bowel prep tolerability. Even though no difference was observed between the two groups with regards to nausea or vomiting, simethicone resulted in less abdominal distension (P = 0.0003) and showed a trend toward less abdominal pain (P = 0.07). This would suggest an increased likelihood of patients completing prep, hence improving the quality of bowel preparation and ultimately reducing the need for repeat colonoscopies.

Our meta-analysis has several strengths. When compared with the two previous meta-analyses conducted on this topic, our sample size was the largest. We analyzed in detail the dose of simethicone, as well as its effect on bowel preparation, colonic bubbles, and ADR. Most of the included studies suggest statistically insignificant trends which, when pooled together, do reach statistical significance. Taking into account the multiple countries included, the patient diversity, and uncomplicated administration of simethicone, we believe these results to be generalizable. The significant heterogeneity between the studies may be a result of multiple factors, including variation in bowel preparation used, dosage and timing of simethicone administration, the different methods used to assess the quality of bowel preparation and the severity of colonic bubbles, and the diet permitted during the few days prior colonoscopy.

There are some limitations. First, as this was a group-level study, it is susceptible to ecological bias. Second, all but one of the studies was only single-blinded. Recent literature has cast doubt on the safety of simethicone use during endoscopy. There are concerns that particles will deposit in the working channel and may be a harbinger of infection despite reprocessing. A recent study by Barakat et al[23] noted increased ATP bioluminescence after using medium and high doses of simethicone through the water pump and after injecting through the working channel. The clinical relevance of this residue is debatable, and no link with increased infection has been established. Most recent outbreaks of endoscopy-related infection are linked with the difficulty in cleaning the elevator mechanism in duodenoscopes. Major endoscope manufacturers recommend either avoiding simethicone use altogether during endoscopy, or using the lowest concentration necessary[24]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends using simethicone in bowel preparation instead of through the endoscope, with the thought that it is less likely to persist in the endoscope[25]. However, this area requires further study.

The results bring us to the question; should simethicone be routinely utilized in addition to standard bowel preparation? Although simethicone is already suggested by American[26] and European[25] clinical guidelines to reduce foaming and to improve tolerability, we feel that simethicone as a colonoscopy adjuvant is currently underutilized by gastroenterologists worldwide. By mixing simethicone with bowel preparation, the need for injection through the endoscope during the procedure would be reduced, allaying concerns about infection.

In conclusion, the addition of medium doses of simethicone to colonoscopy bowel preparation improves the tolerability and quality of bowel preparation and promises improvements in ADR. Simethicone appears to be safe, with a low incidence of adverse events in this pooled analysis.

Colon cancer is the second most common cause of cancer related deaths in both men and women across the world. Colonoscopy is an essential tool that can help screen and prevent it. However, inadequate bowel preparation decreases rate of adenoma detection, increases procedure time; decreasing overall quality of colonoscopy. Antifoaming agents, such as simethicone, may help improve adequate preparation if added to bowel preparation. However, data regarding this is unclear. There is also upcoming data that injection of simethicone through the endoscopy channel may be associated with particle deposition and lead to scope reprocessing infection outbreaks.

So far, it is unclear whether simethicone is effective in increasing adenoma detection rates (ADRs) in different bowel preparation and there is no data on what dose should be used in bowel preparation.

To conduct a meta-analysis to help summarize available data for simethicone use during various bowel preparations, confirm the effect on ADR, bowel prep tolerability and investigate an optimal dose.

Studies related to this topic were searched for in multiple databases. Only 11 studies met the strict inclusion criteria. Two reviewers independently scored the identified studies for methodology and abstracted pertinent data. Review Manager 5 was used to analyze the data.

We were able to show that addition of simethicone to bowel preparation lead to a significant decrease in inadequate bowel preparation and number of colonic bubbles. This resulted in a significant increase in the ADR as well. We also noted higher doses of simethicone (approximately 500 mg) were more effective.

Our study confirms the effectiveness of simethicone use in bowel preparations in helping improve quality of colonoscopies.

Whilst searching for literature, we realized few meta-analyses have effectively analyzed simethicone effectiveness in different bowel preparations and looked at optimal dosage. More studies are needed to investigate an association of simethicone use with bowel preparation with scope reprocessing infection.

| 1. | Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:1490-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1965] [Cited by in RCA: 2350] [Article Influence: 195.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Liao X, Qian ZR, Inamura K, Kim SA, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Imamura Y, Willett WC, Rosner BA, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E, Ogino S, Chan AT. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1095-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 968] [Cited by in RCA: 1186] [Article Influence: 91.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim HW. Inadequate bowel preparation increases missed polyps. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:345-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu L, Cao Y, Liao C, Huang J, Gao F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of Simethicone for gastrointestinal endoscopic visibility. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:227-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 5. | Kim ES, Kim KO, Jang BI, Kim EY, Lee YJ, Lee HS, Jeon SW, Kim HJ, Kim SK; Crohn’s and Colitis Association in Daegu-Gyeongbuk (CCAiD). Comparison of 4-L Polyethylene Glycol and 2-L Polyethylene Glycol Plus Ascorbic Acid in Patients with Inactive Ulcerative Colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2489-2497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gentile M, De Rosa M, Cestaro G, Forestieri P. 2 L PEG plus ascorbic acid versus 4 L PEG plus simethicon for colonoscopy preparation: a randomized single-blind clinical trial. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:276-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McNally PR, Maydonovitch CL, Wong RK. The effect of simethicone on colonic visibility after night-prior colonic lavage. A double-blind randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:650-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Park JJ, Lee SK, Jang JY, Kim HJ, Kim NH. The effectiveness of simethicone in improving visibility during colonoscopy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:1321-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang S, Zheng D, Wang J, Wu J, Lei P, Luo Q, Wang L, Zhang B, Wang H, Cui Y, Chen M. Simethicone improves bowel cleansing with low-volume polyethylene glycol: a multicenter randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2018;50:412-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bai Y, Fang J, Zhao SB, Wang D, Li YQ, Shi RH, Sun ZQ, Sun MJ, Ji F, Si JM, Li ZS. Impact of preprocedure simethicone on adenoma detection rate during colonoscopy: a multicenter, endoscopist-blinded randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2018;50:128-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yoo IK, Jeen YT, Kang SH, Lee JH, Kim SH, Lee JM, Choi HS, Kim ES, Keum B, Chun HJ, Lee HS, Kim CD. Improving of bowel cleansing effect for polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid using simethicone: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Tongprasert S, Sobhonslidsuk A, Rattanasiri S. Improving quality of colonoscopy by adding simethicone to sodium phosphate bowel preparation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3032-3037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Lazzaroni M, Petrillo M, Desideri S, Bianchi Porro G. Efficacy and tolerability of polyethylene glycol-electrolyte lavage solution with and without simethicone in the preparation of patients with inflammatory bowel disease for colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:655-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Altintaş E, Uçbilek E, Sezgin O, Sayici Y. Alverine citrate plus simethicone reduces cecal intubation time in colonoscopy - a randomized study. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2008;19:174-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Matro R, Tupchong K, Daskalakis C, Gordon V, Katz L, Kastenberg D. The effect on colon visualization during colonoscopy of the addition of simethicone to polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution: a randomized single-blind study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2012;3:e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jansen SV, Goedhard JG, Winkens B, van Deursen CT. Preparation before colonoscopy: a randomized controlled trial comparing different regimes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:897-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sudduth RH, DeAngelis S, Sherman KE, McNally PR. The effectiveness of simethicone in improving visibility during colonoscopy when given with a sodium phosphate solution: a double-bind randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:413-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shaver WA, Storms P, Peterson WL. Improvement of oral colonic lavage with supplemental simethicone. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:185-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McNally PR, Maydonovitch CL, Wong RK. The effectiveness of simethicone in improving visibility during colonoscopy: a double-blind randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:255-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Huang J, Liao C, Wu L, Cao Y, Gao F. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing antibacterial therapy with placebo in Crohn's disease. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:617-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pan P, Zhao SB, Li BH, Meng QQ, Yao J, Wang D, Li ZS, Bai Y. Effect of supplemental simethicone for bowel preparation on adenoma detection during colonoscopy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:314-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shiotani A, Opekun AR, Graham DY. Visualization of the small intestine using capsule endoscopy in healthy subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1019-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Barakat MT, Huang RJ, Banerjee S. Simethicone is retained in endoscopes despite reprocessing: impact of its use on working channel fluid retention and adenosine triphosphate bioluminescence values (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:115-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Catalone BJ. Simethicone. Letter to health care practitioner. Center Valley (PA): Olympus 2009; Available from: https://medical.olympusamerica.com/sites/default/files/pdf/SimethiconeCustomerLetter.pdf. |

| 25. | Hassan C, Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, Polkowski M, Rembacken B, Saunders B, Benamouzig R, Holme O, Green S, Kuiper T, Marmo R, Omar M, Petruzziello L, Spada C, Zullo A, Dumonceau JM; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2013;45:142-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE; American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Petretta M, Yang ZP S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ