Published online Dec 18, 2024. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v12.i4.96981

Revised: July 7, 2024

Accepted: September 11, 2024

Published online: December 18, 2024

Processing time: 206 Days and 15.8 Hours

Kinesiophobia is a common condition often manifested in patients with musculoskeletal disorders within the process of rehabilitation. Recently, the literature has been investigating whether Pilates could contribute to the management of kine

To evaluate recordings of the Pilates method in kinesiophobia related to muscu

PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus and Pedro databases were all scrutinized for ran

We have identified five studies, with a total of 366 patients with musculoskeletal disorders. Three of them showed that a Pilates-based intervention by either mat or equipment can combat kinesiophobia in patients with musculoskeletal conditions, while another showed that Pilates exercises with equipment may have better long-term effects on kinesiophobia compared to Pilates mat.

Overall, a strong level of research evidence has been amassed for the Pilates intervention as well as a moderate level of research evidence for the effectiveness of equipment-based Pilates in reducing kinesiophobia in patients with musculoskeletal disorders. While the underlying mechanisms driving such a result remain unknown, it appears that Pilates can influence both biological and psychological factors in musculoskeletal disorders, thus resulting in the management of kinesiophobic behaviours.

Core Tip: Pilates is a type of exercise that promotes body awareness and helps individuals gradually gain functional capacity. The structural and progressive nature of Pilates exercises allows individuals to regain movement through a holistic approach which offers confidence and thus reduces fear of movement which is often associated with musculoskeletal conditions. Several studies have indicated positive results of Pilates in treating kinesiophobia. More well-designed studies would set the principles of tailor-made rehabilitation protocols which would contribute to a more evidence-based, successful and sustained recovery.

- Citation: Sivrika A, Sivrika P, Morakis A, Lamnisos D, Georgoudis G, Stasinopoulos D. Is Pilates an effective tool for the management of kinesiophobia in musculoskeletal disorders? World J Meta-Anal 2024; 12(4): 96981

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v12/i4/96981.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v12.i4.96981

Currently, musculoskeletal disorders are but one major public health problem, affecting approximately 1.71 billion people worldwide[1]. They include a lengthy list of more than 150 different diseases and conditions that affect joints, bones, muscles and in some cases multiple areas or systems of the body (World Health Organization, 2022). They are typically characterized by pain, disability, and limitations in functional capacity, having significant social and economic conse

Pain is common in most musculoskeletal disorders, which may be acute or chronic[4]. In any case, it seems that it can lead to both avoidance and fear of movement in patients, a condition known as kinesiophobia[5]. Specifically, kinesio

Among other things, psychological factors such as fear most likely influence the way people perceive pain. For example, the pain avoidance model (fear avoidance model of pain) as formulated from the Vlaeyen et al[7] and Vlaeyen and Linton[8] suggests that people's perceptions of pain tend to influence their level of mobility in everyday life. Cata

Kinesiophobia is an important prognostic factor in musculoskeletal disorders. A recent global study carried out using the Delphi method concluded that among 35 psychological factors, fear is indeed the most detrimental, affecting the outcome in tendinopathy[11].

Therefore, restriction of movement due to fear of movement has been one of the goals of people in rehabilitation due to musculoskeletal disorders[12]. Emphasis is placed both on physical rehabilitation, the goal of which is to recover the ability to perform daily activities and mobility in general[12,13] as well as in rehabilitation at a psychological level with the aim of controlling and limiting negative perceptions of pain which affect patients' level of mobility in everyday life[14].

The Pilates method is a type of intervention that has been evaluated for its effectiveness in reducing kinesiophobia in patients with musculoskeletal disorders[15,16]. It was developed in the early 20th century by Joseph Pilates, who described it as a controlled exercise that emphasizes the quality and precision of movements, resulting in the im

Research shows that Pilates exercises have positive effects in reducing pain and disability caused by musculoskeletal disorders, such as chronic pain in the lumbar spine[20], chronic pain in the cervical spine[21] osteoporosis[22] and knee osteoarthritis[23]. Some studies have also investigated the effect of Pilates exercises on kinesiophobia[15,16] but no previous systematic review has summarized nor analyzed the results of these studies. A recent study by Domingues de Freitas et al[24] collected data on Pilates and its positive effects on kinesiophobia, however this focused exclusively on patients with chronic lumbar spine pain.

The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the effects of the Pilates method on kinesiophobia related to musculoskeletal disorders.

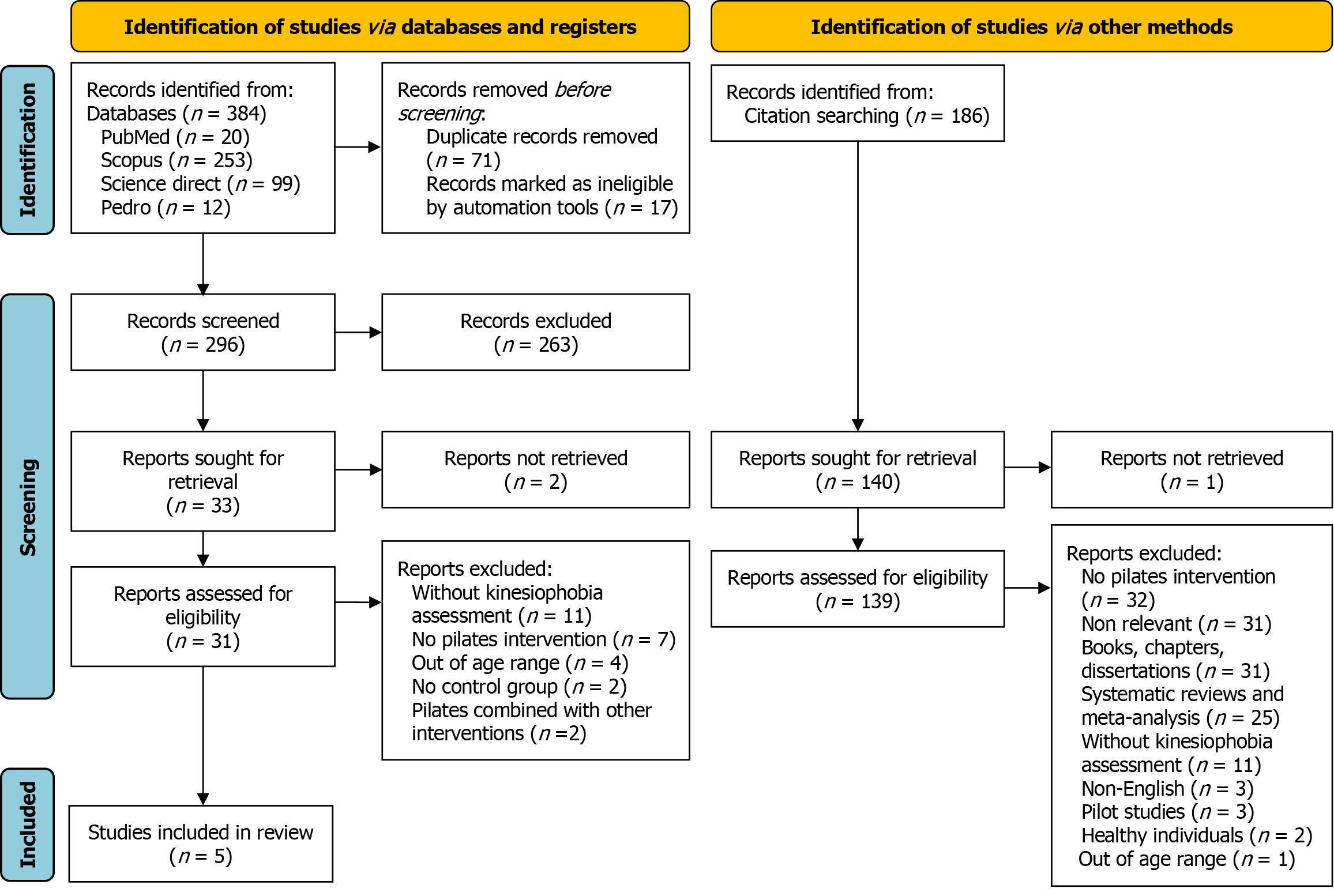

The systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA Guidelines[25] and Guidelines for Conducting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses[26]. The protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (ID: CRD 42023479641). Potential studies were searched and identified in the PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus and Pedro databases for articles published up to and including September 2023. Two authors (A.S. & P.S.) separately searched all available articles using the following word combination and keywords in the title or abstracts of the articles: "kinesiophobia" and "Pilates". The search string in PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus databases was (Pilates OR "clinical Pilates" OR "mat Pilates" OR "equipment-based pilates") AND ("Kinesiophobia" OR "fear of movement"). In the Pedro database, two search procedures were performed using the following two strings: Pilates Kinesiophobia and Pilates “fear of movement". Potential disagreements were resolved with the help of a third author (A.M). Zotero citation management software was used to extract articles from databases, check for duplicates and for the final selection of studies for the systematic review.

The evaluation of the methodological quality of the studies was carried out independently by two authors (A.S & P.S) and was based on Furlan et al's criteria[27]. Studies were assessed against 12 criteria which fall into 6 areas of bias, which are selection bias (3 criteria), attribution bias (4), detection bias (2 criteria), loss bias (2 criteria) and reporting bias (1 criterion); Every criterion is evaluated with 'yes', 'no' or 'unclear'.

The effectiveness of the interventions was assessed using the van Tulder et al[28] research evidence framework. The framework consists of 6 levels of research evidence and essentially constitutes a form of qualitative analysis based on the results of the studies, the evaluation of their methodological quality and the number of RCTs that can be identified for a specific topic.

The primary search of the 4 databases yielded a total of 384 articles, including 71 duplicates and 17 studies that were removed via the automated tools because they were written in a language other than English (Figure 1). Of the 296 articles based on their title and excerpts 263 were removed because they were systematic reviews and meta-analyses (98), were unrelated to the topic (81), were books, book chapters and dissertations (26), were about case studies, pilot studies and study protocols (17), had implemented psychological interventions for kinesiophobia (16) or had implemented other exercise interventions besides Pilates (11), involved patients with conditions not related to the musculoskeletal system (7), were performed in unselected patient populations such as pregnant women and children (5) and were not written in the English language (2). The full text was searched for 33 studies, and finally retrieved for 31 studies. Full-text inclu

From the backward search of the references of the 5 studies, an additional 186 studies were reviewed. The full text was searched for 140 studies after removing 46 duplicates and ultimately retrieved for 139 studies. Full text review of these yielded no additional studies as they were excluded because the intervention was not about Pilates (32), were clearly unrelated to the topic (31), were books, book chapters and dissertations (31), were systematic reviews and meta-analyses (25), involved a Pilates intervention delivered to patients with musculoskeletal disorders but did not assess kinesiophobia as an outcome measure (11), were written in languages other than English (3), were pilot studies (3), were conducted in healthy subjects (2), and patients were outside the age range (1) (Figure 1).

The 5 studies identified from the systematic review included a total of 366 patients with musculoskeletal conditions. The age of the patients had not been predetermined during the selection of subjects in one study[29] but the mean age of patients in the intervention and control groups was within the limits set in the inclusion criteria in the present systematic review. In the remaining 4 studies the age range was 18-50 years in two studies[30,16] and 18-60 years in another two studies[31,32]. Regarding gender, in all studies an over-representation of women (72.6% of all participants) is observed, compared to men. The musculoskeletal conditions examined were chronic non-specific lumbar spine pain in 4 studies[30-32] and chronic non-specific cervical spine pain in 1 study[29] (Table 1).

| Ref. | Sample | Sex | Age | Intervention & control groups | Kinesiophobia | Results | Score |

| Akodu et al[29], 2021 | 34 patients (45 initially) Nonspecific cervical spine pain (CSP) CSPSE: 17 PE: 14 DIE: 14 | Men (42.3%) Women (57.7%) | CSPSE: 47.71 ± 10.02 PE: 47.43 ± 9.22 DIE: 44.93 ± 6.26 There was no pre-set age limit when selecting participants | CSPSE: Cervical spine stabilization exercises PE: Pilates exercises (mat) DIE: Dynamic isometric exercises (control group) | TSK 0, 4, 8 weeks | Significant improvement in TSK in CSPSE & PE No statistically significant differences in PE and DIE, CSPSE at the end of the intervention | 8/12 |

| Cruz-Díaz et al[16], 2018 | 62 patients (64 original) Nonspecific low back pain (LBP) PG: 32 CG: 32 | Men (33.9%) Women (66.1%) | 18-50 PG: 37.90 ± 8.2 CG: 35.60 ± 6.7 | PG: Pilates (ground-mat) CG: Booklet | TSK 0, 6, 12 weeks | Significant improvement in TSK in the PG, compared that CG Significant improvement in TSK in PG at the end of the intervention | 8/12 |

| Cruz-Díaz et al[30], 2017 | 98 patients (132 initially) Nonspecific low back pain PMG: 34 PEG: 34 CG: 34 | Men (35.8%) Women (64.2%) | 18-50 PMG: 36.94 ± 12.46 PEG: 35.50 ± 11.98 CG: 36.32 ± 10.67 | PMG: Pilates mat PEG: Pilates equipment CG: No intervention | TSK 0, 6, 12 weeks | Significant improvement in TSK after the intervention in PMG and PEG, but without significant differences between the three groups at the end of the intervention | 9/12 |

| da Luz et al[31], 2014 | 86 Nonspecific low back pain PMG: 43 PEG: 43 | Men (23.2%) Women (76.8%) | 18-60 PMG: 43.5 ± 8.6 PEG: 38.8 ± 9.9 | PMG: Pilates mat PEG: Pilates equipment | TSK 0, 6 weeks, 6 months | No statistically significant differences in TSK within and between groups at the end of the intervention; significant improvement in TSK 6 months follow-up in Pilates with equipment group (PEG) in relation to Pilates mat group (PMG) | 8/12 |

| Miyamoto et al[32], 2013 | 86 patients Nonspecific low back pain PG: 43 CG: 43 | Men (18.6%) Women (81.4%) | 18-60 PG: 40.7 ± 11.8 CG: 38.3 ± 11.4 | PG: Pilates mat CG: Booklet | TSK 0, 6 weeks, 6 months | No improvement in both groups | 8/12 |

The studies in the systematic review contain a minimal risk of bias, as 4 of them met 8 of the 12 criteria[16,29,31,32] and one met 9 of 12 criteria[30]. With the exception of Akodu et al[29] study where it is not clear, the method of randomization was adequate in the remaining four studies, as the procedure was performed either with a computer-generated random sequence[31], or with consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes[16,30,32]. In four of the studies there was concealment of the therapeutic intervention[16,30-32]. The blinding of patients was ensured only in the Akodu et al[29] study but the nature of the interventions could not ensure blinding of therapists in any of the studies. In contrast, blinding of outcome measure assessors was ensured in all studies. Dropout rates were acceptable in all studies, although marginally at 20% in Akodu et al[29] study, while the data for all participants were also analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized. No selective reporting of results was identified in any of the studies.

However, the intervention and control groups were not similar in their baseline characteristics in three different studies. Specifically in the research of Cruz-Díaz et al[16] body mass index was statistically significantly different between groups before the intervention, even though at the end of the intervention there was no difference. In the da Luz et al[31] study patients who had received physical therapy in the previous 6 months were not excluded and there are differences in the percentage of patients who did or did not receive physical therapy in the two groups. Finally, in Miyamoto et al's study a difference in the duration of patients' symptoms was observed between the intervention and control groups[32].

The criterion of avoiding concomitant interventions was not met in two studies: In the Miyamoto et al's study[32], par

In all studies in the systematic review, kinesiophobia was assessed with the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK). It is a 17-item self-report scale that assesses fear of movement or re-injury in patients with musculoskeletal disorders. Scores can range from 17 (no fear) to 68 (high fear)[33].

In three studies, the assessments were carried out in an interim period before the end of the intervention[16,29,30], while in two studies, a long-term evaluation was done, 6 months after the end of the intervention[31,32].

At the end of the Akodu et al[29] study showed a statistically significant difference in TSK values between the control group and the group that received neck stabilization exercises, but no differences were found for the group that received the Pilates exercises (P = 0.072) (Table 3). It is noted, however, that over time (comparison between the beginning and the end of the intervention), both Pilates exercises and neck stabilization exercises improved statistical TSK values significantly (P = 0.001 for the Pilates group). In the study by Cruz-Díaz et al[30], the two intervention groups (equipment Pilates and mat Pilates) showed statistically significant improvements in TSK scores over time (P < 0.05), but at the end of the intervention the scale scores were not statistically significantly different between the three groups (P > 0.05).

| Ref. | Baseline MV (SD) | Intermediate measurement, MV (SD) | End of intervention, MV (SD) | Follow-up, MV (SD) | P value, baseline-finish | P value, baseline–follow up |

| Akodu et al[29], 2021 | CSPSE: 40.17 ± 3.16 PE: 40.82 ± 2.44 DIE: 39.73 ± 2.28 | 4th week CSPSE: 37.38 ± 3.20 PE: 39.46 ± 1.85 DIE: 39.79 ± 2.19 | 8th week CSPSE: 33.17 ± 3.27 PE: 37.27 ± 1.95 DIE: 38.36 ± 3.36 | - | P = 0.072 P = 0.001 | - |

| Cruz-Díaz et al[16], 2018 | Mean value PG: 34.50 CG: 34.00 | 6 th week Mean value PG: 27.50 CG: 33.00 | 12 th week Mean value PG: 27.50 CG: 32.50 | - | P < 0.001 | - |

| Cruz-Díaz et al[30], 2017 | PMG: 34.52 ± 4.14 PEG: 36.50 ± 3.92 CG: 33.90 ± 4.23 | 6th week PMG: 32.23 ± 3.06 PEG: 34.08 ± 4.1 CG: 34.26 ± 3.96 | 12th week PMG: 31.73 ± 3.24 PEG: 32.00 ± 3.56 CG: 34.10 ± 4.04 | - | P < 0.05 | - |

| da Luz et al[31], 2014 | PMG: 39.7 ± 8.1 PEG: 39.6 ± 8.0 | - | 6th week PMG: 35.3 ± 6.6 PEG: 34.1 ± 7.8 | 6th month PMG: 40.0 ± 9.9 PEG: 34.9 ± 7.9 | P > 0.05 | P < 0.001 |

| Miyamoto et al[32], 2013 | PG: 39.4 ± 6.1 CG: 39.5 ± 7.1 | - | 6th week PG: 36.3 ± 7.4 CG: 38.1 ± 8.3 | 6 th month PG: 38.1 ± 7.2 CG: 38.9 ± 7.3 | P = 0.20 | P = 0.61 |

In Cruz-Díaz et al[16] study, the group that received a Pilates-based intervention significantly improved TSK scores over time (P < 0.001), and in addition had a statistically significantly greater improvement compared to the control group, both in the intermediate assessment, as well as in the assessment carried out post intervention (P < 0.001). In da Luz et al[31] research TSK scores showed no statistically significant improvements by the end of the intervention in either group, while no statistically significant differences were reported between the two groups. However, the differences between the two groups were statistically significant in the long-term assessment, with better scores for the Pilates equipment group than the mat Pilates group (P < 0.001). Finally, in the Miyamoto et al[32] study, no statistically significant differences were found between the intervention and control groups at the end of the intervention (P = 0.20), nor in the long-term evaluation (P = 0.61).

Pilates-based intervention (mat or equipment) can improve kinesiophobia in patients with chronic musculoskeletal conditions[16,29,30], while one study shows that Pilates exercises with equipment may have better long-term results in kinesiophobia compared to mat Pilates[31] (Table 3).

Based on Furlan et al[27] criteria, studies showed positive findings, a low risk of bias with rates from 66.6%-75% and low loss rates.

Of the five studies, one[29] compared distinct types of exercise, was of high methodological quality and at the end of the intervention showed positive results with differences that were not statistically significant between groups. Based on van Tulder et al's level of research evidence, no research evidence emerges[28].

The next category includes three studies[16,30,32] where an intervention was carried out with Pilates exercises and minimal[16,32] to no intervention[30]. The studies were of high methodological quality, while in two of the three[16,30] the results of the intervention with Pilates exercises were positive. Based on van Tulder et al's level of research evidence, strong research evidence emerges[28].

The third category includes the study of da Luz et al[31] who studied the effect of Pilates mat exercises versus equip

Kinesiophobia is an outcome measure that affects musculoskeletal conditions as it has been associated with greater levels of fear of pain and avoidance of physical movement[34]. It often appears and develops during treatment and progression of musculoskeletal disorders, and its inadequate treatment and management can enhance functional disability, contribute to the chronicity of symptoms, and delay the positive results of rehabilitation programs[8,35,36].

These results have been reported in a variety of patient publications with musculoskeletal disorders. In a systematic review of 63 studies, Luque-Suarez et al[5] found that a greater level of kinesiophobia is a predictive factor of pain severity and progression of disability level in musculoskeletal disorders such as chronic lumbar and cervical spine pain, knee osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and chronic knee pain. In patients with chronic shoulder pain Martinez-Calderon et al[37] found that greater pain catastrophizing perceptions and kinesiophobia were positively and strongly associated with pain intensity and the recovery procedure.

The present systematic review focused on investigating the effect of the Pilates method on kinesiophobia, in patients with musculoskeletal disorders. Overall, Pilates has a favorable effect on reducing the symptoms of kinesiophobia. These improvements were observed on Pilates programs versus control groups that had received either another exercise intervention[29], an informational intervention[16], or no treatment whatsoever[30]. The minimum duration of the programs was 6 weeks[16,30] and 8 weeks[29]. In total, three randomized studies[16,29,30] presented a positive effect of Pilates on kinesiophobia while two studies had no significant improvements in kinesiophobia[31,32]. It appears that Pilates exercises have strong research evidence against no or minimal intervention but none when compared to other forms of exercise and moderately in favor of equipment exercises over mat exercises.

Similar results were reached by Domingues de Freitas et al[24] in a systematic review, investigating the effect of Pilates on kinesiophobia in patients with chronic low back pain. They presented a moderate level of research evidence for Pilates exercises. In the present systematic review, however, a study conducted in patients with chronic cervical spine pain was also included[29]. This enhances the diversification of studies, but on the other hand, it broadens the scope of musculoskeletal disorders, in which Pilates could be applied to reduce kinesiophobia. No relevant studies in patients with other types of musculoskeletal disorders were found, while chronic low back pain is the focus of research interest in this research area.

The positive effect of Pilates on kinesiophobia has been suggested in other studies. Miyamoto et al[32] found a 4.2-point reduction in TSK scores in patients with chronic low back pain following a 6-week Pilates intervention. A secondary analysis of the above results conducted by Wood et al[38] resulted that Pilates exercises in patients with chronic low back pain had a positive impact on kinesiophobia and the catastrophizing perception of the feeling of pain and thus moderated pain intensity and functional capacity. These findings highlight the importance of addressing kinesiophobia in rehabilitation programs to achieve better functional outcomes in patients with musculoskeletal disorders. They additionally emphasize the role of psychological factors in rehabilitation and the need to study the underlying factors that affect the relationship between Pilates exercises and positive results in kinesiophobia.

It is paramount to bear in mind that interventions for kinesiophobia need to be based on both physiological and psychological factors. Studies support that several multifactorial approaches to rehabilitation, both physical and psychological, may be more effective in reducing kinesiophobia in patients with musculoskeletal disorders, compared to interventions based only on exercise or only on a psychological procedure[39]. Monticone et al[40] concluded that spinal stabilization exercises combined with cognitive behavioral therapy produced statistically significant improvements in pain, disability, kinesiophobia and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain. In a recent systematic review, Huang et al[14] concluded that multimodality treatment protocols are more effective in reducing kinesiophobia than exercise-only protocols. Sinikallio et al[41] suggests that psychological treatments for kinesiophobia and pain affect mechanisms such as self-efficacy, positive emotions, and pain expectations in patients with musculoskeletal disorders. Furthermore, the fear of movement due to pain is an automatic process and in terms of brain function is based on established correlations and occurs involuntarily[42].

From this viewpoint, Pilates is a suitable form of exercise due to its particular characteristics and its mindful perspective[43]. Adams and Quin[43] state that the mind-body connection approach is a feature that makes Pilates particularly effective as a rehabilitation tool, as it recognizes the importance of kinesthetic awareness in effective physical and mental rehabilitation. Pilates strengthens body awareness and positive mental attitude, developing mindfulness[44]. In turn, pain mindfulness proves to be a good emotional and cognitive pain management strategy through focused and non-judgmental awareness of sensations, emotions and thoughts that arise and are related to pain[45]. These positive effects of developing pain awareness on pain management and perception have also been found in patients with chronic low back pain[46] as well as in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain[47].

Additionally, the types of exercise that favor the mind-body connection, such as Pilates, follow an approach of coupling physical activity and a temporary mental state of self-awareness[48]. This characteristic of Pilates exercises is not found in conventional types of exercise, such as aerobic and strength exercises[49]. Mind-body exercises activate inherent energy and maximize self-control of emotions, allowing practitioners to control negative mental states[50], such as those associated with or caused by experiences of pain and stress[51]. It is well known that the human experience of pain is not just physical, but is influenced by mental and emotional factors, such as memories, previous pain experiences and stress[52]. In Pilates in particular, the control of body movements through the mind is requested[18] and Pilates interventions could potentially contribute not only to improvements to physical function, but also to the psyche[17] through effects in areas such as concentration, attention span, and the release of negative thoughts[49]. Pilates could therefore be beneficial for conditions such as kinesiophobia which have a psychological background. The above could constitute possible mechanisms through which Pilates works beneficially in kinesiophobia.

Additionally, the psychological benefits of Pilates are well documented in the literature. Pilates exercises have been linked to improvements in depressive symptomatology, anxiety and stress levels, feelings of vitality and deep energy pools as opposed to fatigue, and a variety of mental health dimensions of quality-of-life elements[53]. In elderly patients with musculoskeletal diseases, Meikis et al[54] found a moderate to high positive effect of Pilates on psychological factors (quality of life, depression, sleep quality, fear of heights) as well as physiological parameters (muscle strength, balance, endurance, flexibility). Increased serotonin levels have been suggested as a possible mechanism for the significant improvement in depressive symptoms in older women following their participation in a 12-week Pilates program[55].

Given the positive results of Pilates in the treatment of kinesiophobia, many groups of patients with musculoskeletal disorders could benefit from such an exercise approach in clinical practice. In patients with Achilles tendinopathy, Vivekanantha et al[56] concluded that higher TSK scale scores were associated with increased levels of pain, decreased quality of life, and increased self-reported disorder severity. Psychosocial factors, including kinesiophobia, are associated with symptoms such as Achilles tendon stiffness[57]. Additionally, the prevalence of kinesiophobia has been shown to be higher in patients with AT, compared to patients with other musculoskeletal disorders[58]. While no study was identified that included the application of Pilates in AT to reduce kinesiophobia, research that has examined the effectiveness of interventions that follow a biopsychosocial perspective and/or multimodal approaches have found improvements in patients' pain and physical function[59].

In conclusion, Pilates is an exercise approach that could positively affect the psychological components of kinesio

In practice, the results of the systematic review could be exploited by clinical Pilates providers in the rehabilitation of musculoskeletal conditions in order to set the presuppositions for the selection of exercises depending on the musculoskeletal disorder, the stage, the tissues involved as well as the progressivity based on the principles in rehabilitation. What's more, the choice of exercises needs to take into account the personal psychological factors that have an etiological background in kinesiophobia in the context of the biopsychosocial model proposed in rehabilitation. Generally, rehabilitation programs in kinesiophobia emphasize the importance of biopsychosocial approaches, where, while defining rehabilitation goals, individual factors that contribute to the development of feelings of fear and avoidance of movement and physical activity should be taken into consideration[60,61]. Clinical Pilates providers may consider modifying exercises to better target the recognized psychological components of kinesiophobia and provide customized and well-designed protocols. These approaches should emphasize on enhancing patients' sense of safety and their ability to perform exercises, reducing fear of movement and physical activity, which could predispose them to avoid movement, physical inactivity and in deterioration of their musculoskeletal health.

Musculoskeletal disorders are accompanied by anxiety, depression and kinesiophobia, affecting both the course of rehabilitation and the lives of patients at all levels. The "perception" of pain causes fear of movement, provokes and preserves a vicious cycle resulting in functional incapacity.

Exercise interventions affect psychological factors such as kinesiophobia. Pilates, is based on the control of movement, requires mindfulness in execution and affects both biological and psychological factors in musculoskeletal disorders with an unknown mechanism at present. The indications of the effectiveness of the method in the management of kine

We would like to thank D Stasinopoulos, D Lamnisos, G Georgoudis for their continuous support in conducting the systematic review.

| 1. | Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, Hanson SW, Chatterji S, Vos T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;396:2006-2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 1560] [Article Influence: 312.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Malik KM, Beckerly R, Imani F. Musculoskeletal Disorders a Universal Source of Pain and Disability Misunderstood and Mismanaged: A Critical Analysis Based on the U.S. Model of Care. Anesth Pain Med. 2018;8:e85532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gallagher S, Barbe MF. Musculoskeletal Disorders. First published: June 3, 2022. Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2022. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Main CJ, Williams AC. Musculoskeletal pain. BMJ. 2002;325:534-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Luque-Suarez A, Martinez-Calderon J, Falla D. Role of kinesiophobia on pain, disability, and quality of life in people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:554-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Knapik A, Saulicz E, Gnat R. Kinesiophobia - introducing a new diagnostic tool. J Hum Kinet. 2011;28:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vlaeyen JWS, Kole-Snijders AMJ, Boeren RGB, van Eek H. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62:363-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1571] [Cited by in RCA: 1607] [Article Influence: 51.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vlaeyen JWS, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85:317-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3079] [Cited by in RCA: 3139] [Article Influence: 120.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thomas EN, Pers YM, Mercier G, Cambiere JP, Frasson N, Ster F, Hérisson C, Blotman F. The importance of fear, beliefs, catastrophizing and kinesiophobia in chronic low back pain rehabilitation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U, Weiser S, Bachmann LM, Brunner F. Fear-avoidance beliefs-a moderator of treatment efficacy in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J. 2014;14:2658-2678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stubbs C, McAuliffe S, Chimenti RL, Coombes BK, Haines T, Heales L, de Vos RJ, Lehman G, Mallows A, Michner LA, Millar NL, O'Neill S, O'Sullivan K, Plinsinga M, Rathleff M, Rio E, Ross M, Roy JS, Silbernagel KG, Thomson A, Trevail T, van den Akker-Scheek I, Vicenzino B, Vlaeyen JWS, Pinto RZ, Malliaras P. Which Psychological and Psychosocial Constructs Are Important to Measure in Future Tendinopathy Clinical Trials? A Modified International Delphi Study With Expert Clinician/Researchers and People With Tendinopathy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2024;54:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen YK, Zheng JQ, Hou MJ, Chai YT, Lin ZL, Liu BK, Liu L, Fu SX, Wang XB. Are rehabilitation interventions effective for kinesiophobia and pain in osteoarthritis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials; 2022. Preprint. Cited 7 July 2024. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Castanho B, Cordeiro N, Pinheira V. The Influence of Kinesiophobia on Clinical Practice in Physical Therapy: An Integrative Literature Review. IJMRHS 2021; 10: 78-94. Available from: https://www.ijmrhs.com/medical-research/the-influence-of-kinesiophobia-on-clinical-practice-in-physical-therapy-an-integrative-literature-review-74368.html. |

| 14. | Huang J, Xu Y, Xuan R, Baker JS, Gu Y. A Mixed Comparison of Interventions for Kinesiophobia in Individuals With Musculoskeletal Pain: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;13:886015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Oksuz S, Unal E. The effect of the clinical pilates exercises on kinesiophobia and other symptoms related to osteoporosis: Randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2017;26:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cruz-Díaz D, Romeu M, Velasco-González C, Martínez-Amat A, Hita-Contreras F. The effectiveness of 12 weeks of Pilates intervention on disability, pain and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32:1249-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Contreras J. Is It Time to Rethink Pilates? SportsPhysio 2018; 3: 10-12. Available from: https://physiosports.com.au/is-it-time-to-rethink-pilates/. |

| 18. | Wells C, Kolt GS, Bialocerkowski A. Defining Pilates exercise: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:253-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hoffman J, Gabel CP. The origins of Western mind-body exercise methods. Phys Ther Rev. 2015;20:315-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Eliks M, Zgorzalewicz-Stachowiak M, Zeńczak-Praga K. Application of Pilates-based exercises in the treatment of chronic non-specific low back pain: state of the art. Postgrad Med J. 2019;95:41-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Martini JD, Ferreira GE, Xavier de Araujo F. Pilates for neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2022;31:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rocha RSB, Rocha VDS, Rocha LDB, Da Silva ML. Effect of the pilates method on people with osteoporosis: a systematic review. Mtprehabjournal. 2022;20. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Saleem N, Zahid S, Mahmood T, Ahmed N, Maqsood U, Chaudhary MA. Effect of Pilates based exercises on symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Pak Med Assoc. 2022;72:8-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Domingues de Freitas C, Costa DA, Junior NC, Civile VT. Effects of the pilates method on kinesiophobia associated with chronic non-specific low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2020;24:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51705] [Article Influence: 10341.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Editor(s): Julian PT Higgins, Sally Green. First published: September 22, 2008; Systematic Reviews of Interventions . [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8311] [Cited by in RCA: 6805] [Article Influence: 141.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 27. | Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M; Editorial Board, Cochrane Back Review Group. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1929-1941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1129] [Cited by in RCA: 1295] [Article Influence: 76.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L; Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:1290-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1300] [Cited by in RCA: 1352] [Article Influence: 58.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Akodu AK, Nwanne CA, Fapojuwo OA. Efficacy of neck stabilization and Pilates exercises on pain, sleep disturbance and kinesiophobia in patients with non-specific chronic neck pain: A randomized controlled trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2021;26:411-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 30. | Cruz-Díaz D, Bergamin M, Gobbo S, Martínez-Amat A, Hita-Contreras F. Comparative effects of 12 weeks of equipment based and mat Pilates in patients with Chronic Low Back Pain on pain, function and transversus abdominis activation. A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2017;33:72-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | da Luz MA Jr, Costa LO, Fuhro FF, Manzoni AC, Oliveira NT, Cabral CM. Effectiveness of mat Pilates or equipment-based Pilates exercises in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2014;94:623-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Miyamoto GC, Costa LO, Galvanin T, Cabral CM. Efficacy of the addition of modified Pilates exercises to a minimal intervention in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2013;93:310-320.. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | French DJ, France CR, Vigneau F, French JA, Evans RT. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic pain: a psychometric assessment of the original English version of the Tampa scale for kinesiophobia (TSK). Pain. 2007;127:42-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Trost Z, France CR, Thomas JS. Examination of the photograph series of daily activities (PHODA) scale in chronic low back pain patients with high and low kinesiophobia. Pain. 2009;141:276-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G. Outline of a Fear-Avoidance Model of exaggerated pain perception--I. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21:401-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 787] [Cited by in RCA: 815] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Trocoli TO, Botelho RV. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and kinesiophobia in patients with low back pain and their association with the symptoms of low back spinal pain. Rev Bras Reumatol Engl Ed. 2016;56:330-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Martinez-Calderon J, Struyf F, Meeus M, Luque-Suarez A. The association between pain beliefs and pain intensity and/or disability in people with shoulder pain: A systematic review. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;37:29-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Wood L, Bejarano G, Csiernik B, Miyamoto GC, Mansell G, Hayden JA, Lewis M, Cashin AG. Pain catastrophising and kinesiophobia mediate pain and physical function improvements with Pilates exercise in chronic low back pain: a mediation analysis of a randomised controlled trial. J Physiother. 2023;69:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Xu Y, Song Y, Sun D, Fekete G, Gu Y. Effect of Multi-Modal Therapies for Kinesiophobia Caused by Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Monticone M, Ambrosini E, Rocca B, Magni S, Brivio F, Ferrante S. A multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme improves disability, kinesiophobia and walking ability in subjects with chronic low back pain: results of a randomised controlled pilot study. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:2105-2113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sinikallio SH, Helminen EE, Valjakka AL, Väisänen-Rouvali RH, Arokoski JP. Multiple psychological factors are associated with poorer functioning in a sample of community-dwelling knee osteoarthritis patients. J Clin Rheumatol. 2014;20:261-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Goubran M, Farajzadeh A, Lahart IM, Bilodeau M, Boisgontier MP. Physical activity and kinesiophobia: A systematic review and meta-analysis; 2023. Preprint. Cited 7 July 2024. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Adams M, Quin R. The Pilates teacher training manual. Boone, NC: Appalachian State University, 2007. |

| 44. | Adams M, Caldwell K, Atkins L, Quin R. Pilates and Mindfulness: A Qualitative Study. JoDE. 2012;12:123-130. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review of the evidence. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17:83-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Luiggi-Hernandez JG, Woo J, Hamm M, Greco CM, Weiner DK, Morone NE. Mindfulness for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Qualitative Analysis. Pain Med. 2018;19:2138-2145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Rezaei S, Hassanzadeh S. Are mindfulness skills associated with reducing kinesiophobia, pain severity, pain catastrophizing and physical disability? Results of Iranian patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. HPR. 2019;7:276-285. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | La Forge R. Mind-body fitness: encouraging prospects for primary and secondary prevention. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 1997;11:53-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kim S, Shim J, Han G. The Effect of Mind-Body Exercise on Sustainable Psychological Wellbeing Focusing on Pilates. Sustainability. 2019;11:1977. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Schure MB, Christopher J, Christopher S. Mind–Body Medicine and the Art of Self‐Care: Teaching Mindfulness to Counseling Students Through Yoga, Meditation, and Qigong. J Counseling & Develop. 2008;86:47-56. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Hassed C. Mind-body therapies--use in chronic pain management. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42:112-117. [PubMed] |

| 52. | De Souza LH, Frank AO. Subjective pain experience of people with chronic back pain. Physiother Res Int. 2000;5:207-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Fleming KM, Herring MP. The effects of pilates on mental health outcomes: A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. 2018;37:80-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Meikis L, Wicker P, Donath L. Effects of Pilates Training on Physiological and Psychological Health Parameters in Healthy Older Adults and in Older Adults With Clinical Conditions Over 55 Years: A Meta-Analytical Review. Front Neurol. 2021;12:724218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Mokhtari M, Nezakatalhossaini M, Esfarjani F. The Effect of 12-Week Pilates Exercises on Depression and Balance Associated with Falling in the Elderly. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013;70:1714-1723. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Vivekanantha P, de Sa D, Halai M, Daniels T, Del Balso C, Pinsker E, Shah A. Kinesiophobia contributes to worse functional and patient-reported outcome measures in Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:5199-5206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Chimenti RL, Post AA, Silbernagel KG, Hadlandsmyth K, Sluka KA, Moseley GL, Rio E. Kinesiophobia Severity Categories and Clinically Meaningful Symptom Change in Persons With Achilles Tendinopathy in a Cross-Sectional Study: Implications for Assessment and Willingness to Exercise. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2021;2:739051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Smitheman HP, Lundberg M, Härnesand M, Gelfgren S, Grävare Silbernagel K. Putting the fear-avoidance model into practice - what can patients with chronic low back pain learn from patients with Achilles tendinopathy and vice versa? Braz J Phys Ther. 2023;27:100557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Chimenti RL, Post AA, Rio EK, Moseley GL, Dao M, Mosby H, Hall M, de Cesar Netto C, Wilken JM, Danielson J, Bayman EO, Sluka KA. The effects of pain science education plus exercise on pain and function in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a blinded, placebo-controlled, explanatory, randomized trial. Pain. 2023;164:e47-e65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Bordeleau M, Vincenot M, Lefevre S, Duport A, Seggio L, Breton T, Lelard T, Serra E, Roussel N, Neves JFD, Léonard G. Treatments for kinesiophobia in people with chronic pain: A scoping review. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:933483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | John JN, Ugwu EC, Okezue OC, Ekechukwu END, Mgbeojedo UG, John DO, Ezeukwu AO. Kinesiophobia and associated factors among patients with chronic non-specific low back pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45:2651-2659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, revise, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/