Published online Dec 20, 2023. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v13.i5.502

Peer-review started: May 24, 2023

First decision: August 10, 2023

Revised: August 26, 2023

Accepted: September 11, 2023

Article in press: September 11, 2023

Published online: December 20, 2023

Processing time: 210 Days and 0.8 Hours

The ExeterTM Universal cemented femoral component is widely used for total hip replacement surgery. Although there have been few reports of femoral com

A 54-year-old man with a Dorr A femur sustained a refracture of a primary Ex

Re-fracture of a modern femoral ExeterTM stem is a rare event, but technical complications related to revision surgery can lead to this outcome. The cortical window osteotomy technique can facilitate the removal of a broken stem and cement, allowing for prosthetic re-implantation under direct vision and avoiding ETO-related complications.

Core Tip: We analyzed the causes of failure in a patient with an Exeter stem refracture, and discussed how to resolve it using a known but little used technique. When removing a broken stem, a window osteotomy facilitates the extraction of the distal cement and allows for prosthetic reimplantation, thereby minimizing the complications of an extended osteotomy. Finally, this preoperative technique, if correctly planned, can be performed by using ordinary instruments and does not consume host bone. This technique should be an addition to the armamentarium of a revision hip surgeon when faced with the challenge of extracting a fracture cemented femoral stem.

- Citation: Lucero CM, Luco JB, Garcia-Mansilla A, Slullitel PA, Zanotti G, Comba F, Buttaro MA. Successful hip revision surgery following refracture of a modern femoral stem using a cortical window osteotomy technique: A case report and review of literature. World J Methodol 2023; 13(5): 502-509

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v13/i5/502.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v13.i5.502

Femoral stem fracture is a rare complication in total hip replacement (THR). Over the years, the stems have been redesigned and failure has been greatly minimized because of improved designs, the use of modern materials, and better cementation techniques[1]. The ExeterTM stem (Stryker, Newbury, United Kingdom) has shown excellent long-term survival[2,3]. Fractures are an extremely rare complication with a rate of around 0.2%[4,5]. Fracture of this particular design has already been reported, and was mainly associated with the original stem in the 70s[6-9]. However, as far as we are concerned, presented here is the first case of a re-fracture of an ExeterTM stem in the same patient. Removal of a broken femoral component is a technically demanding procedure and several techniques have been described to treat this complication[10-14] and to preserve as much bone as possible. In this case report, we described a patient with an ExeterTM stem re-fracture, analyzed the possible causes of this complication and surgically managed the case by using a simple technique that aimed to preserve bone and the abductor mechanism.

The patient's chief complaint involves post-operative hip pain, with an absence of concomitant traumatic antecedents.

A 54-year-old man [170 cm, 90 kg, body mass index (BMI) 31.1 kg/m2] was admitted to another center 7 years ago for a one-stage bilateral THR due to osteoarthritis.

Five years later, he started to develop pain in his right thigh without previous trauma and was diagnosed with a fracture in the mid-proximal third of the femoral stem (Figure 1A and B). On reviewing his postoperative note, an ExeterTM V40TM/TridentTM X3TM (Stryker, Newbury, United Kingdom) hybrid right THR was implanted through a postero-lateral approach, using a 44 mm stem and a 50 mm cup was placed with a 32 mm ceramic (alumina) BioloxTM Forte (CeramTec, Plochingen, Germany) femoral head and a 10 highly cross-linked polyethylene (HXLPE). At revision surgery, the broken femoral stem was removed using an ETO, and a new ExeterTM V40TM stem was implanted by employing a CWC using the same stem size as the first intervention (Figure 1C). The patient evolved favorably without pain and returned to his functional status. Two years after revision the patient came to our institution, presenting pain in the operated limb, without reporting any associated trauma. Antero-posterior (AP) X-ray of both hips was taken, showing a new fracture of the right stem at the level of the mid-distal third, without apparent bone fracture and with the distal cement mantle undamaged (Figure 1D). The patient was scheduled for a femoral revision with a cement-less distal fixation stem. A minimally invasive window on the lateral cortex of the femur was made, to extract the cement mantle and the distal part of the fractured stem.

The information in question was not required for the case report.

The information in question was not required for the case report.

Two years after revision the patient came to our institution, presenting pain in the operated limb, without reporting any associated trauma.

The information in question was not required for the case report.

AP X-ray of both hips was taken, showing a new fracture of the right stem at the level of the mid-distal third, without apparent bone fracture and with the distal cement mantle undamaged (Figure 1D).

New fracture of the right stem at the level of the mid-distal third, without apparent bone fracture and with the distal cement mantle undamaged.

The following technique provides a method of “windowing” the femur, facilitating cement removal and firm fixation of the new prosthesis, in this case, an uncemented distally-fixed, RestorationTM Modular stem (Stryker, Newbury, United Kingdom). Preoperative radiographs must include an AP pelvic radiography covering both hips. Femoral radiographs should include the whole bone in AP as well as lateral (L) views. Calibration of the image is recommended in order to detect Dorr A narrow femoral canals like this one in which an uncemented, distally-fixed stem may not easily fit. In this case we used the known diameter of the failed femoral head, which was 32 mm, to calibrate the radiographs.

The patient was placed on the lateral decubitus position, with two anterior and one posterior supports in order to keep the pelvis stable and well-oriented during the whole surgery. A postero-lateral approach was used. The length was calculated with the previous preoperative planning on the radiography, measuring the distance from the tip of the greater trochanter to the end of the cement and the cement restrictor. The fascia lata and gluteal fascia were divided in line with skin incision. The fibers of the gluteus maximus were separated bluntly in line with skin incision. The sciatic nerve was then identified and protected.

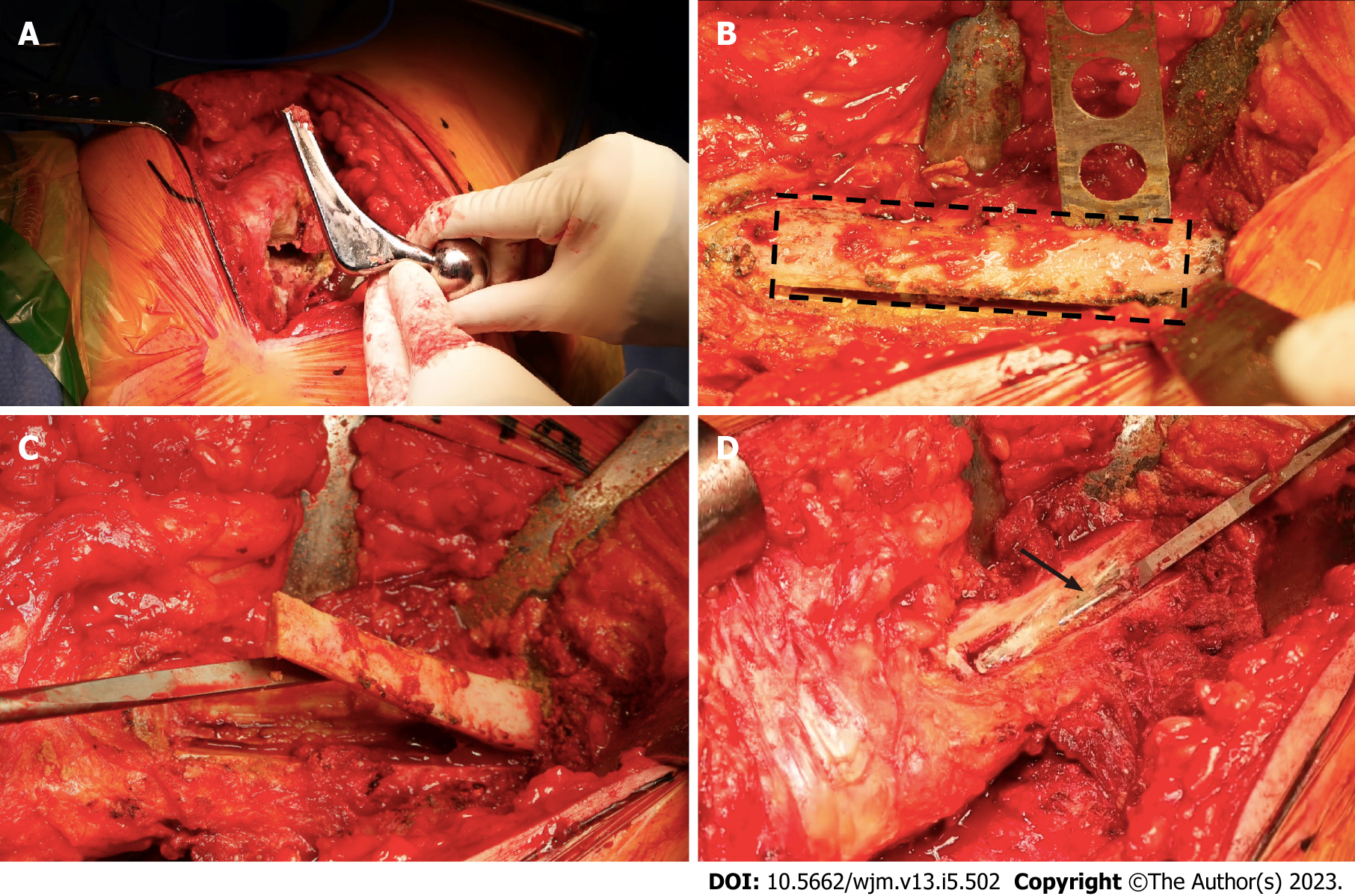

When the patient reported a history of more than one revision, the fascia might have been scarred with the vastus externus, and dissection should be performed to separate these two different structures. Once the plane has been divided, a Charnley retractor was positioned, taking both sides of the fascia lata. The proximal cement and the proximal part of the fractured stem were removed with specially-designed chisels that had to be inserted between the cement and the bone, and then the cement was gently smashed with a light hammer (Figure 2A). All the proximal cement that was under direct vision was removed proximally, leaving the unseen polymethylmethacrylate and the cement restrictor to be resected through the cortical window. Direct vision of the removal prevented a cortical femoral perforation that could lead to an intraoperative femoral fracture. All necrotic tissues, pseudomembranes end cement were removed in order to maximize contact between the uncemented revision stem and the host bone. A cement chisel was introduced into the femoral canal, with the leg in the femoral position in order to measure the length of the cement where the tip of the stem was implanted. The vastus lateralis was detached and the cortical window was drawn with a surgical marker (Figure 2B). The cortical window could be made laterally or anterolaterally. The first option makes it easier for the surgeon to perform the windowing and to remove cement under direct vision. The second option has been advocated by some authors for its benefit of a lower incidence of postoperative femoral fracture[16]. But in all the cases this window is indicated, a longer stem bypassing at least 2 diaphyseal femoral diameters must be implanted.

The cortical window was made with a narrow saw in order to achieve maximal control of the cut (Figure 2B) and then it was detached with gentle chiseling (Figure 2C). The window was kept in a soaked swab until the femoral reconstruction was complete. Once the cement mantle was partially removed with a cement chisel, the fractured distal part of the cemented stem could be observed under direct vision. The next step was to impact the fractured stem from its tip in order to remove it retrogradely (Figure 2D). The window also allows for direct vision of the cement mantle as well as the cement restrictor. The distal part of the Exeter stem was removed. It is important to notice that this Exeter stem has been deficiently cemented proximally, and well-cemented distally, but the surgeon forgot to use the centralizer, which is of utmost importance for the proper functioning of this implant.

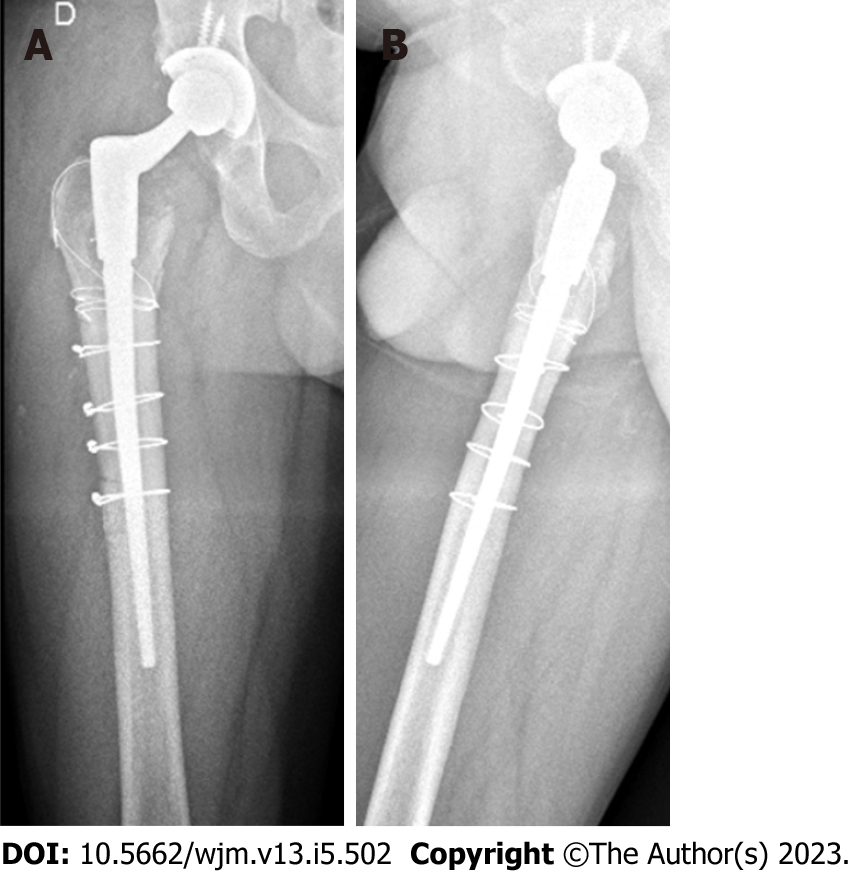

Femoral broaching was performed in order to achieve good contact between the host bone and the distal fixation stem. After this, the definitive conical distal stem was impacted into the femoral canal as preoperatively planned, under direct vision through the window, to achieve rotational stability and prevent subsidence (Figure 3A and B). Proximal cone reaming was then performed to prepare for the cone body placement. A BioloxTM Delta (CeramTec, Plochingen, Germany) 32 mm ceramic femoral head was implanted, retaining the highly cross-linked polyethylene, which was in good condition. Finally, reduction, stability test and limb length measurement were performed. Once procedure was finished, the cortical window was covered and fixed with wire cerclages (Figure 3C). Final postoperative AP X-rays exhibited excellent implant alignment, and the femoral windows was correctly bypassed with the new implant (Figure 3D).

Postoperative, routine exercises included isometric exercises of the lower limbs and ambulation with a walker was allowed as tolerated from the first postoperative day. 48 h later, the patient was discharged home, with good pain tolerance and without clinical complications. Six months after operation, the patient had no limitations in activities of daily living. The most recent radiographic control showed stable prosthetic implants in correct position, and complete healing of the window osteotomy (Figure 4A and B).

This case report describes two consecutive mechanical complications of a polished tapered high offset stem in a 54-year-old man having receiving operation in another center. The patient had a BMI > 30 and a femur with a Dorr A narrow medullary canal. Of note, a revision surgery was performed by employing a similar surgical technique, adding an ETO and using the CWC technique, and inserting an implant with the identical characteristics, that led to a refracture of the femoral stem. In our institution, the patient was revised to an uncemented distal fixation modular prosthesis, by removing the fractured stem through a femoral cortical window, allowing immediate full load as tolerated. The benefits of cortical windows are that this technique allows for easy removal of distal cement mantle or, as in this case, also the distal part of a broken cemented stem. Moreover, the osteotomized part can be easily fixed with some cerclage wires, it does not compromise the abductor mechanism, the patient has no restrictions to prevent a damage of this mechanism, and the stem can be fixed to an intact major trochanter, which is not possible when an ETO is performed. Furthermore, an ETO could have led to pseudoarthrosis, lack of proximal support and a new stem fracture.

In certain cases, as in Dorr A femurs, primary hip arthroplasty can be challenging. These femurs have strong thick cortices where uncemented fixation could be related to incomplete fitting of the stem because this one gets stuck in the proximal diaphysis before metaphyseal fixation occurs. Short partial neck preserving stems corresponding to the type 2B of the Khanuja et al[17] classification, could be an alternative in young patients with Dorr A femurs, since the fixation is more proximal and the femoral canal could be less invaded[18].

Since the introduction of the ExeterTM Universal Stem in 1988, there have been many reports on stem fracture, with the cause being multifactorial[19-25]. Factors such as poor medial support, insufficient proximal cement mantle, varus orientation of the stem, and increased patient weight (or a combination of these factors) have been considered. Fracture of the femoral component of the cemented total hip prosthesis is a rare but documented complication[26], with incidence ranging from 0.23% to 10.7%. In the current case, implantation of an under-sized stem, usually in a "champagne glass" femur, contributed to fracture in the body of the prosthesis. Although the fracture of a polished conical femoral stem is a rare event, a defect in the cementation technique can lead to a higher stress and suffices to increase the risk of fatigue rupture even in non-obese patients. Moreover, as reported by O'Neill et al[27], the cement-in-cement revision could also predispose stems to the breakage of a polished stem, probably because the the new stem must be proximally implanted, with less cement mantle, which would lead to poor metaphyseal fixation, thus generating a probable cantilever effect. For this reason, the 125 mm Exeter 44 mm offset stem was developed specifically for cement-in-cement revision, being 25 mm shorter than the standard stem and narrower in the distal and antero-posterior directions.

One of the main technical problems with a broken femoral stem is the removal of the distal part and its cement mantle. ETO is a popular and reproducible technique that can resolve most complications in a complicated THR, such as infection, aseptic loosening or a periprosthetic fracture. However, it is not without complications, and nonunion, subsidence, and trochanteric migration with subsequent Trendelenburg, at considerable rates, have been described[28-31]. The time to healing of the osteotomy and the restriction on immediate postoperative weight-bearing are considerable aspects when executing it. Several reports have described multiple methods to facilitate cement extraction and minimize complications during the procedure[32,33]. However, most of them require a protracted surgical time and may be associated with perforations of the femoral cortices or inadvertent intraoperative fractures[34].

Nelson et al[35] developed the original cortical window technique in 1980, creating a window on the lateral aspect of the femur. Klein et al[36], in a series of 21 THR revisions using a window made in the antero-lateral aspect of the femur to extract the distal cement, attained good results with an osteotomy consolidation rate of 17 wk, without thigh pain or loosening. The benefits of cortical windows are that this technique allows for easy removal of distal cement or, as in this case, also the distal part of a broken cemented stem. Moreover, the osteotomy can be easily fixed with two or three cerclage wires, it does not compromise the abductor mechanism, the patient has no restrictions to prevent the damage of this mechanism, and the stem can be fixed to an intact major trochanter, which is not possible when ETO is performed. Although preoperative planning of the window length is mandatory, it is possible to extend it if the surgeon needs to.

We analyzed the causes of failure in a patient with an Exeter stem refracture, and discussed how to resolve it using a known but little used technique. When removing a broken stem, a window osteotomy facilitates the extraction of the distal cement and allows for prosthetic reimplantation, thereby minimizing the complications of an extended osteotomy. Finally, this preoperative technique, if correctly planned, can be performed by using ordinary instruments and does not consume host bone. This technique should be an addition to the armamentarium of a revision hip surgeon when faced with the challenge of extracting a fracture cemented femoral stem.

| 1. | Bolland BJ, Wilson MJ, Howell JR, Hubble MJ, Timperley AJ, Gie GA. An Analysis of Reported Cases of Fracture of the Universal Exeter Femoral Stem Prosthesis. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:1318-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lewthwaite SC, Squires B, Gie GA, Timperley AJ, Ling RS. The Exeter Universal hip in patients 50 years or younger at 10-17 years' followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:324-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Westerman RW, Whitehouse SL, Hubble MJW, Timperley AJ, Howell JR, Wilson MJ. The Exeter V40 cemented femoral component at a minimum 10-year follow-up: the first 540 cases. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B:1002-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fowler JL, Gie GA, Lee AJ, Ling RS. Experience with the Exeter total hip replacement since 1970. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:477-489. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gie GA, Ling RS, Timperley AJ. Stem fracture with the Exeter prosthesis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:206-207. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Charnley J. Fracture of femoral prostheses in total hip replacement. A clinical study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;105-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Busch CA, Charles MN, Haydon CM, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Macdonald SJ, McCalden RW. Fractures of distally-fixed femoral stems after revision arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1333-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Andriacchi TP, Galante JO, Belytschko TB, Hampton S. A stress analysis of the femoral stem in total hip prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:618-624. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ishaque BA, Stürz H, Basad E. Fatigue fracture of a short stem hip replacement: a failure analysis with electron microscopy and review of the literature. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:665.e17-665.e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Laffosse JM. Removal of well-fixed fixed femoral stems. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:S177-S187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tóth K, Sisák K, Nagy J, Manó S, Csernátony Z. Retrograde stem removal in revision hip surgery: removing a loose or broken femoral component with a retrograde nail. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:813-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wroblewski BM. Fractured stem in total hip replacement. A clinical review of 120 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1982;53:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moreland JR, Marder R, Anspach WE Jr. The window technique for the 283 removal of broken femoral stems in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986:245-249. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Harris WH, White RE Jr; Mitchel S, Barber F. A new technique for removal of broken femoral stems in total hip 279 replacement. A technical note. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:843-845. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Dorr LD, Faugere MC, Mackel AM, Gruen TA, Bognar B, Malluche HH. Structural and cellular assessment of bone quality of proximal femur. Bone. 1993;14:231-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 691] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zweymüller KA, Steindl M, Melmer T. Anterior windowing of the femur diaphysis for cement removal in revision surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:227-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Khanuja HS, Vakil JJ, Goddard MS, Mont MA. Cementless femoral fixation in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:500-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Buttaro MA, Slullitel PA, Oñativia JI, Nally F, Andreoli M, Salcedo R, Comba FM, Piccaluga F. 4- to 8-year complication analysis of 2 'partial collum' femoral stems in primary THA. Hip Int. 2021;31:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Davies BM, Branford White HA, Temple A. A series of four fractured Exeter™ stems in hip arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95:e130-e132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | van Doorn WJ, van Biezen FC, Prendergast PJ, Verhaar JA. Fracture of an exeter stem 3 years after impaction allografting--a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73:111-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hamlin K, MacEachern CF. Fracture of an Exeter Stem: A Case Report. JBJS Case Connect. 2014;4:e66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Røkkum M, Bye K, Hetland KR, Reigstad A. Stem fracture with the Exeter prosthesis. 3 of 27 hips followed for 10 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yates PJ, Quraishi NA, Kop A, Howie DW, Marx C, Swarts E. Fractures of modern high nitrogen stainless steel cemented stems: cause, mechanism, and avoidance in 14 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:188-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Swarts E, Kop A, Jones N, Keogh C, Miller S, Yates P. Microstructural features in fractured high nitrogen stainless steel hip prostheses: a retrieval study of polished, tapered femoral stems. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;84:753-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Reito A, Eskelinen A, Pajamäki J, Puolakka T. Neck fracture of the Exeter stem in 3 patients: A cause for concern? Acta Orthop. 2016;87:193-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Buttaro M, Comba F, Zanotti G, Piccaluga F. Fracture of the C-Stem cemented femoral component in revision hip surgery using bone impaction grafting technique: report of 9 cases. Hip Int. 2015;25:184-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | O'Neill GK, Maheshwari R, Willis C, Meek D, Patil S. Fracture of an Exeter 'cement in cement' revision stem: a case report. Hip Int. 2011;21:627-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shi X, Zhou Z, Shen B, Yang J, Kang P, Pei F. The Use of Extended Trochanteric Osteotomy in 2-Stage Reconstruction of the Hip for Infection. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1470-1475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Levine BR, Della Valle CJ, Lewis P, Berger RA, Sporer SM, Paprosky W. Extended trochanteric osteotomy for the treatment of vancouver B2/B3 periprosthetic fractures of the femur. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:527-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sheridan GA, Galbraith A, Kearns SR, Curtin W, Murphy CG. Extended trochanteric osteotomy (ETO) fixation for femoral stem revision in periprosthetic fractures: Dall-Miles plate versus cables. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28:471-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Levine BR, Della Valle CJ, Hamming M, Sporer SM, Berger RA, Paprosky WG. Use of the extended trochanteric osteotomy in treating prosthetic hip infection. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:49-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Razzano CD. Removal of methylmethacrylate in failed total hip arthroplasties. An improved technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;181-182. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Eftekhar NS. Rechannelization of cemented femur using a guide and drill system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;29-31. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | McElfresh EC, Coventry MB. Femoral and pelvic fractures after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:483-492. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Nelson CL, Weber MJ. Technique of windowing the femoral shaft for removal of bone cement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;336-337. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Klein AH, Rubash HE. Femoral windows in revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;164-170. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Argentina

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oommen AT, India S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH