Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.114871

Revised: October 26, 2025

Accepted: November 14, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 84 Days and 16.1 Hours

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major independent stroke risk factor. This study characterizes 22-year national trends and disparities in stroke mortality among United States adults with CKD.

To evaluate 22-year national trends and demographic disparities in stroke mortality among United States adults with CKD to inform targeted strategies for reducing cerebrovascular risk in this vulnerable population.

Using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research Multiple Cause-of-Death data (1999-2020), we analyzed stroke deaths (underlying cause) with CKD (contributing cause) among adults ≥ 25 years. Age-adjusted mortality rates per 100000 population were calculated. Joinpoint regression estimated annual percentage changes (APCs) and average APCs with 95% confidence intervals, stratified by sex, race/ethnicity, region, and urbanization.

Among 37308 stroke deaths with CKD, the overall age-adjusted stroke mortality rates (AAMR) declined from 1.08 (95%CI: 1.03-1.13) in 1999 to 0.71 (95%CI: 0.68-0.75) in 2020 (average annual percent change: -1.79%). Significant trends included a decline from 1999-2009 (APC: -4.25%), followed by an increase from 2009-2012 (APC: 23.25%), a sharp decline from 2012-2015 (APC: -28.10%), and another increase from 2015-2020 (APC: 8.72%). Males had higher mortality than females (AAMR 0.79 vs 0.71). Non-Hispanic Black individuals had the highest AAMR (1.95), followed by Hispanic (0.87) and Non-Hispanic White individuals (0.63). Regionally, the West had the highest AAMR (0.89). State-level mortality varied more than three-fold (District of Columbia: 1.27 vs Arizona: 0.38). Small metropolitan areas had the highest urbanization-stratified AAMR.

While stroke mortality among United States adults with CKD significantly declined over two decades, reflecting improvements in prevention and management, substantial disparities persist. The findings underscore the critical need for targeted public health interventions to address underlying biological, structural, and systemic determinants of cerebrovascular risk in this vulnerable population.

Core Tip: This national study examines 22-year trends in stroke mortality among United States adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD), a high-risk population often overlooked in cerebrovascular research. Using population-level mortality data, we identified periods of both decline and resurgence in mortality, along with striking disparities by sex, race/ethnicity, region, and urbanization. Non-Hispanic Black individuals and residents of small metropolitan areas experienced the greatest burden. These findings highlight evolving epidemiologic patterns and the urgent need for targeted, equity-driven interventions to reduce stroke mortality in adults with CKD.

- Citation: Ibrahim M, Ahmad MA, Mansoor A, Ali H, Sahil F. Temporal trends and disparities in stroke mortality among adults with chronic kidney disease in the United States, 1999-2020. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 114871

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/114871.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.114871

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major public health crisis, affecting over 35 million adults in the United States, equivalent to 15% of the adult population with alarmingly low diagnosis rates exceeding 90%[1]. This condition extends beyond renal impairment, functioning as a potent multiplier of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk. Stroke, the fifth leading cause of United States mortality in 2021, claims approximately 795000 lives annually while incurring economic costs surpassing $56 billion[2]. Crucially, CKD independently elevates stroke susceptibility through non-traditional pathways, including uremic toxin-mediated endothelial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and disrupted cerebral autoregulation[3,4].

Robust epidemiological evidence confirms a dose-dependent relationship between CKD severity and stroke incidence. For every 10 mL/minute/1.73 m2 decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate, stroke risk increases by 7%[5]. Similarly, each 25 mg/mmoL rise in albumin-creatinine ratio corresponds to an 11% higher stroke hazard[6], persisting after adjustment for hypertension, diabetes, and other conventional risk factors[7]. These associations underscore CKD as a distinct neurovascular risk entity rather than a mere comorbidity.

Despite these established linkages, national mortality assessments in CKD populations remain disproportionately focused on aggregate cardiovascular outcomes. Recent analyses describe only modest 7.1% declines in overall cardio

To address these limitations, we conducted the first nationwide, 22-year analysis (1999-2020) of stroke-specific mortality trends exclusively in CKD patients. Leveraging Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) comprehensive mortality database, this study uniquely quantifies age-adjusted stroke mortality rates (AAMRs) across sex, racial/ethnic, and urbanization subgroups; Identifies inflection points in mortality trends using Joinpoint regression; Examines state-level disparities to guide targeted public health interventions. By elucidating heretofore uncharacterized disparities, our findings aim to catalyze precision interventions for this high-risk population.

This study analyzed stroke-related mortality among United States adults aged 25 years and older with CKD from 1999 to 2020 using data from the CDC WONDER platform. Specifically, records were retrieved from the Multiple Cause-of-Death Public Use Files, where stroke was documented as the underlying cause and CKD as a contributing cause of death. CDC WONDER is a comprehensive, publicly accessible source of United States health data available since 1999[10].

Stroke and CKD deaths were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes I60.x, I61.x, I63.x, I64, I69.0, I69.1, I69.3, I69.4, and N18, respectively. Individuals under 25 years of age were excluded due to small case counts in this group. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines and did not require Institutional Review Board approval, as the data were de-identified and publicly available[11].

Variables extracted included year of death, sex, race/ethnicity, geographic region, place of death, urbanization category, and United States state. Death locations were classified into four categories: Hospitals, homes, hospices, and nursing home/Long-term care facilities. Urbanization levels were defined using the National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural classification system, including large central metro, large fringe metro, medium metro, small metro, micropolitan, and noncore (non-metro) areas.

Race/ethnicity was categorized as NH Asian or Pacific Islander, Non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black or African American, and Hispanic or Latino. NH American Indian or Alaska Native were excluded due to low counts or unreliable data. Regional classification followed the United States Census Bureau definitions for Northeast, Midwest, South, and West.

Crude mortality rates per 100000 were calculated annually by dividing the number of stroke deaths among CKD patients by the United States population for that year. AAMRs were standardized using the 2000 United States standard population to allow valid comparisons across time and demographic groups by minimizing age-related confounding.

Temporal trends in AAMRs were assessed using the Joinpoint Regression Program (version 5.0.2), which fits log-linear models to determine annual percentage changes (APCs) and average annual percentage changes, with 95% confidence intervals. The Monte Carlo permutation method was used to identify significant trend changes (joinpoints). An APC was considered statistically significant if its slope differed from zero with a two-sided P value ≤ 0.05[12].

Between 1999 and 2020, a total of 37308 deaths were recorded due to stroke among individuals aged 25 years and older with CKD. Of these, 19440 deaths occurred in females (52.11%) and 17868 in males (47.89%) (Supplementary Table 1).

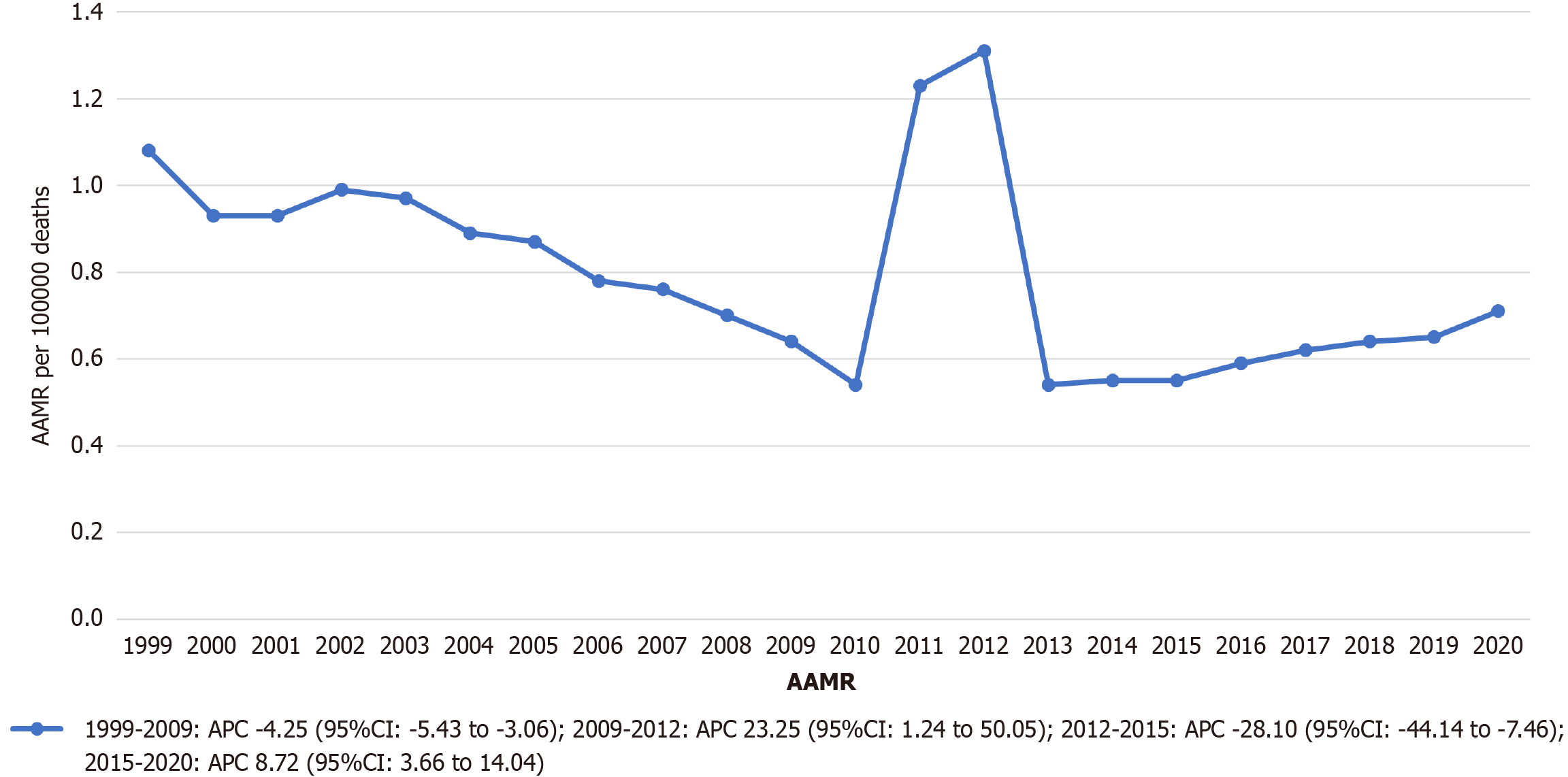

The age-adjusted mortality rate (AAMR) for stroke among individuals with CKD showed fluctuations over the 22-year study period, declining from 1.08 deaths per 100000 population in 1999 (95%CI: 1.03-1.13) to 0.71 in 2020 (95%CI: 0.68-0.75). The overall average annual percent change was -1.79 (95%CI: -5.85 to 2.45).

Between 1999 and 2009, the AAMR experienced a statistically significant reduction, with an APC of -4.25 (95%CI: -5.43 to -3.06). This was followed by a significant upward trend between 2009 and 2012 (APC: 23.25; 95%CI: 1.24 to 50.05). From 2012 to 2015, a sharp statistically significant decline occurred (APC: -28.10; 95%CI: -44.14 to -7.46). Finally, between 2015 and 2020, the rate increased significantly (APC: 8.72; 95%CI: 3.66-14.04) (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2).

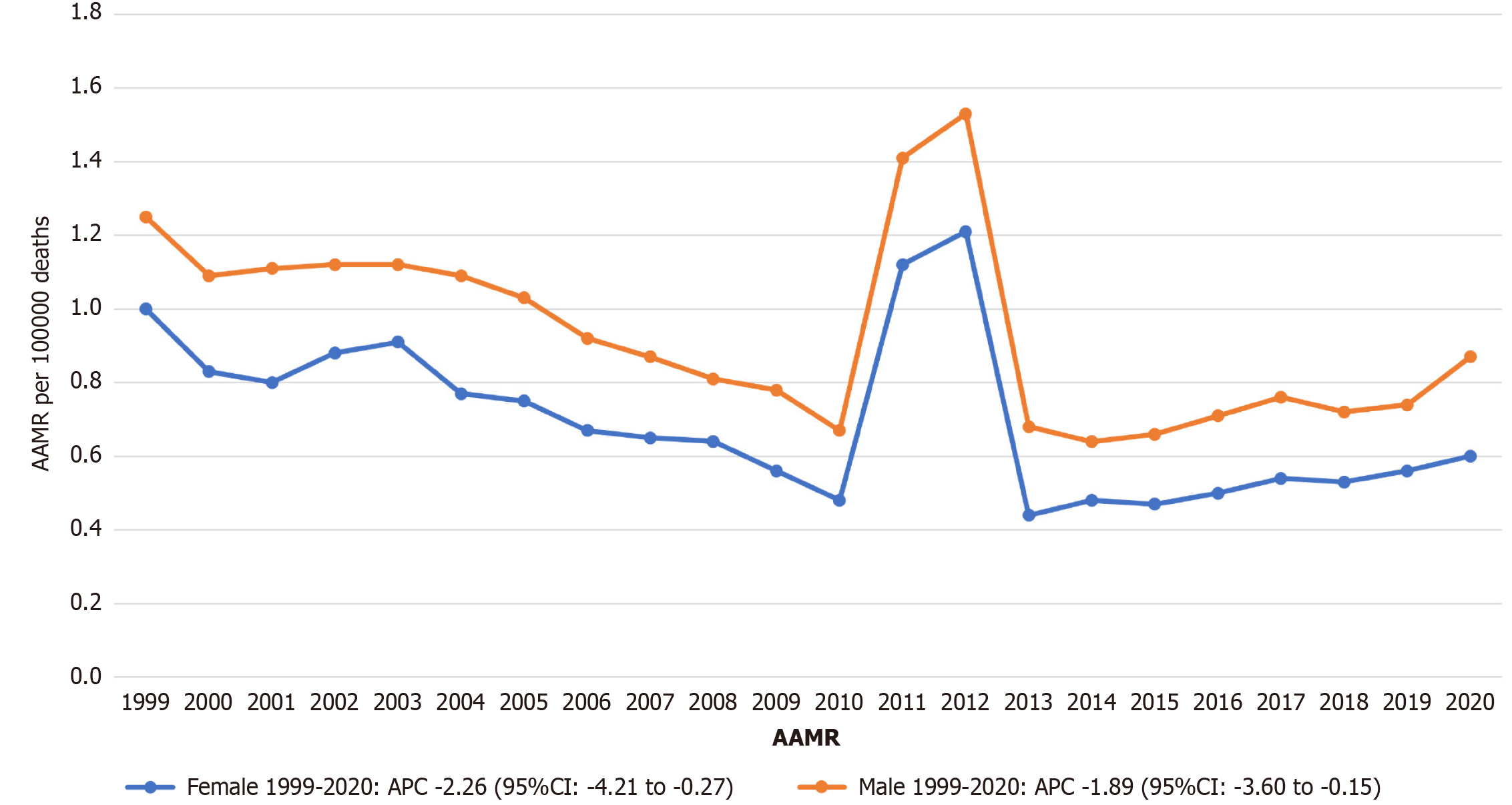

Throughout the study period, males exhibited consistently higher AAMRs for stroke with CKD compared to females. The overall AAMR among males was 0.79 per 100000 (95%CI: 0.78-0.80), whereas for females it was 0.71 (95%CI: 0.70-0.72).

For females, the AAMR declined significantly from 1.00 in 1999 (95%CI: 0.94-1.06) to 0.60 in 2020 (95%CI: 0.56-0.64), with a statistically significant overall decreasing trend across the entire period (APC: -2.26; 95%CI: -4.21 to -0.27).

For males, the AAMR decreased from 1.25 in 1999 (95%CI: 1.17-1.34) to 0.92 in 2020 (95%CI: 0.91-0.94), also showing a statistically significant overall decline (APC: -1.89; 95%CI: -3.60 to -0.15). No joinpoints were identified in either group, indicating consistent monotonic trends throughout 1999-2020 (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3).

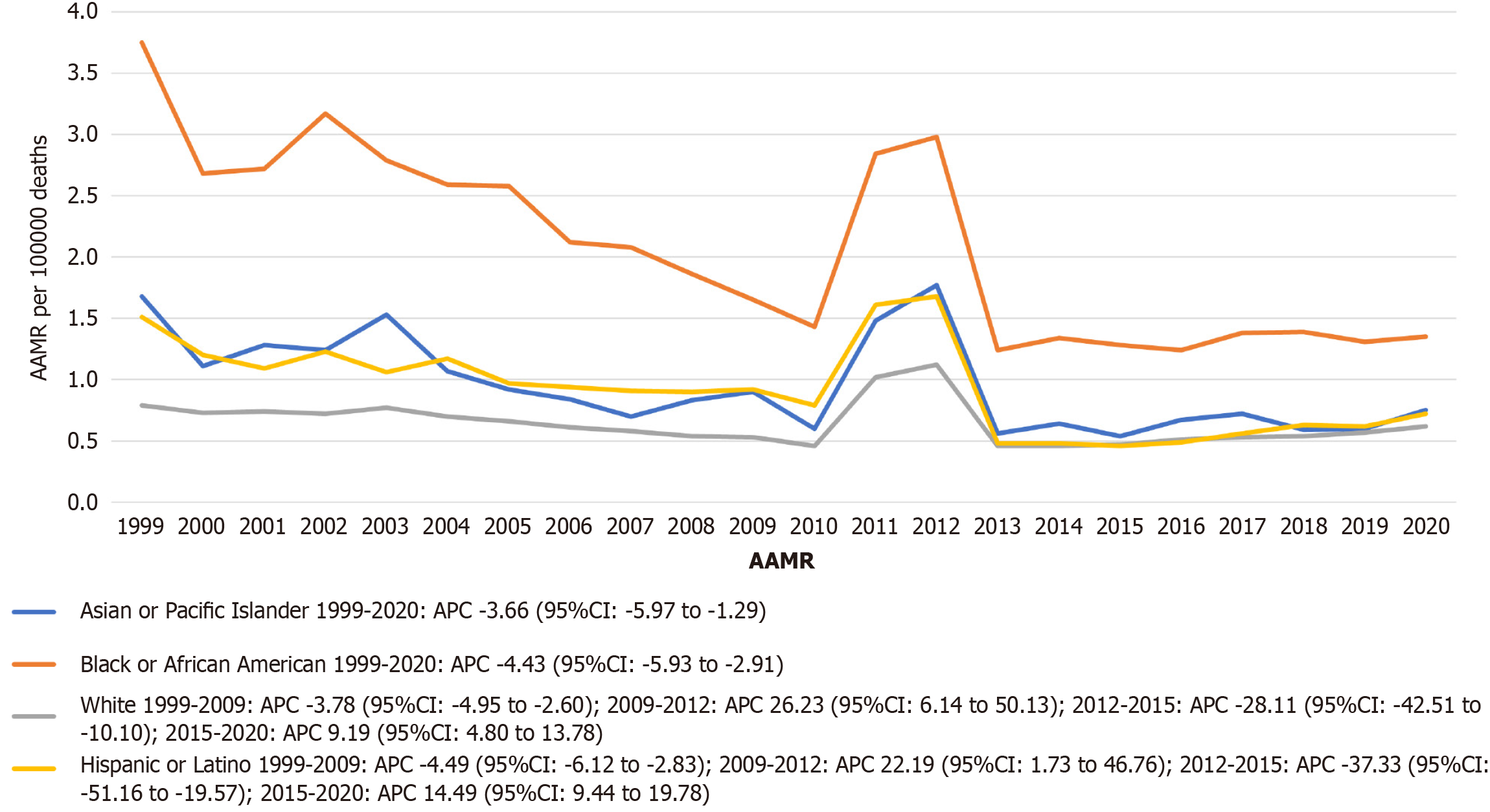

When stratified by race and ethnicity, Black or African American individuals exhibited the highest overall AAMR for stroke with CKD at 1.95 per 100000 population (95%CI: 1.91-2.00), followed by Hispanic or Latino individuals at 0.87 (95%CI: 0.84-0.91), Asian or Pacific Islander individuals at 0.85 (95%CI: 0.81-0.90), and White individuals at 0.63 (95%CI: 0.63-0.64). Asian or Pacific Islander individuals demonstrated a statistically significant monotonic decline over the entire 22-year period (APC: -3.66; 95%CI: -5.97 to -1.29), as did Black or African American individuals (APC: -4.43; 95%CI: -5.93 to -2.91).

In contrast, White individuals experienced significant fluctuations: A decline from 1999-2009 (APC: -3.78; 95%CI: -4.95 to -2.60), followed by an increase during 2009-2012 (APC: 26.23; 95%CI: 6.14-50.13), a sharp decline from 2012-2015 (APC: -28.11; 95%CI: -42.51 to -10.10), and finally an increase from 2015-2020 (APC: 9.19; 95%CI: 4.80-13.78).

Similarly, Hispanic or Latino individuals showed a significant decline (1999-2009: APC: -4.49; 95%CI: -6.12 to -2.83), fol

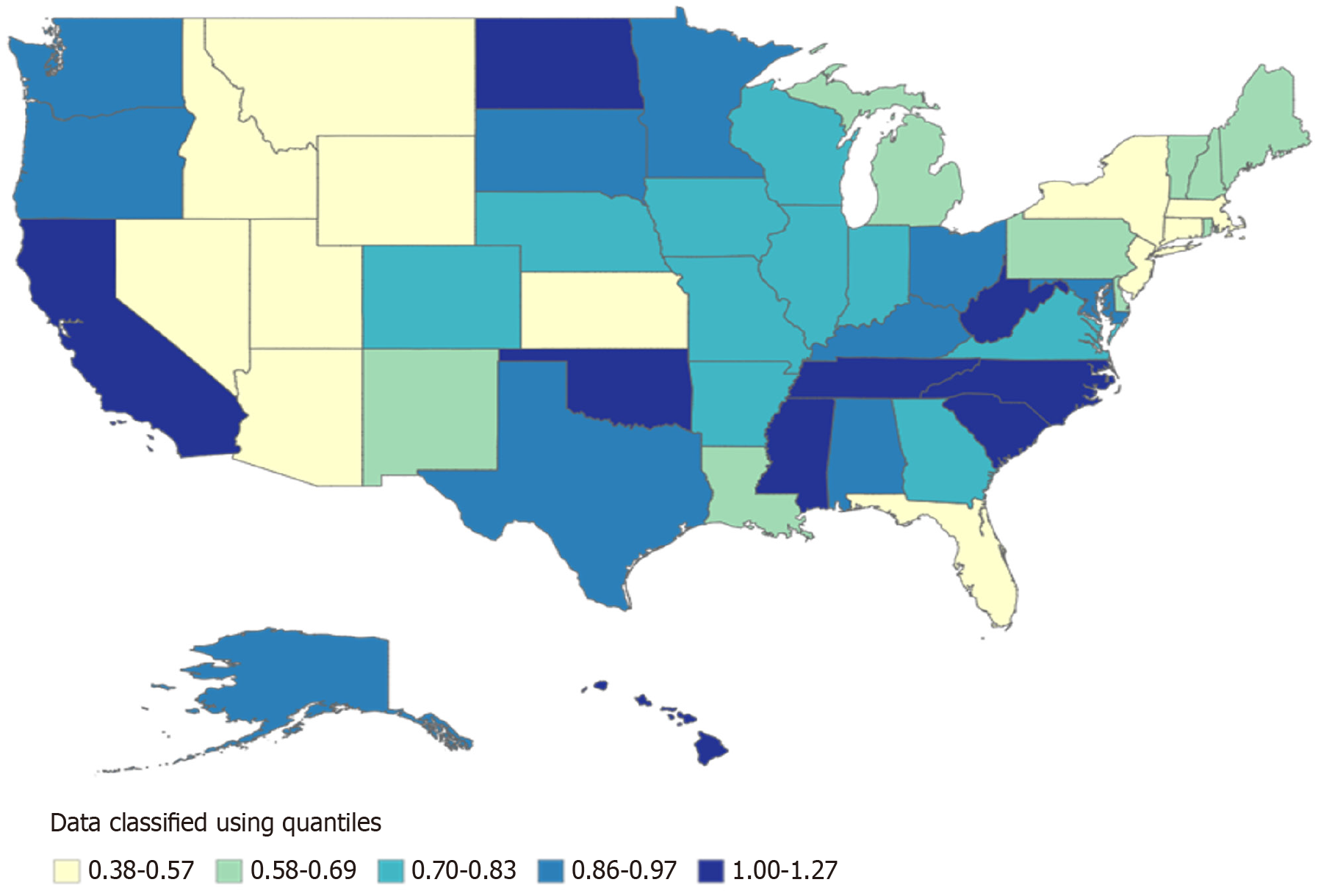

AAMRs demonstrated substantial variation across United States. The highest AAMR was observed in the District of Columbia at 1.27 per 100000 population (95%CI: 1.03-1.52), followed by South Carolina (1.24; 95%CI: 1.16-1.33), West Virginia (1.17; 95%CI: 1.05-1.29), and Mississippi (1.11; 95%CI: 1.01-1.21). In contrast, the lowest rates were recorded in Arizona (0.38; 95%CI: 0.34-0.42), New York (0.40; 95%CI: 0.38-0.42), and Nevada (0.42; 95%CI: 0.35-0.48) (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 5). A choropleth map (Figure 4) illustrates these geographic disparities.

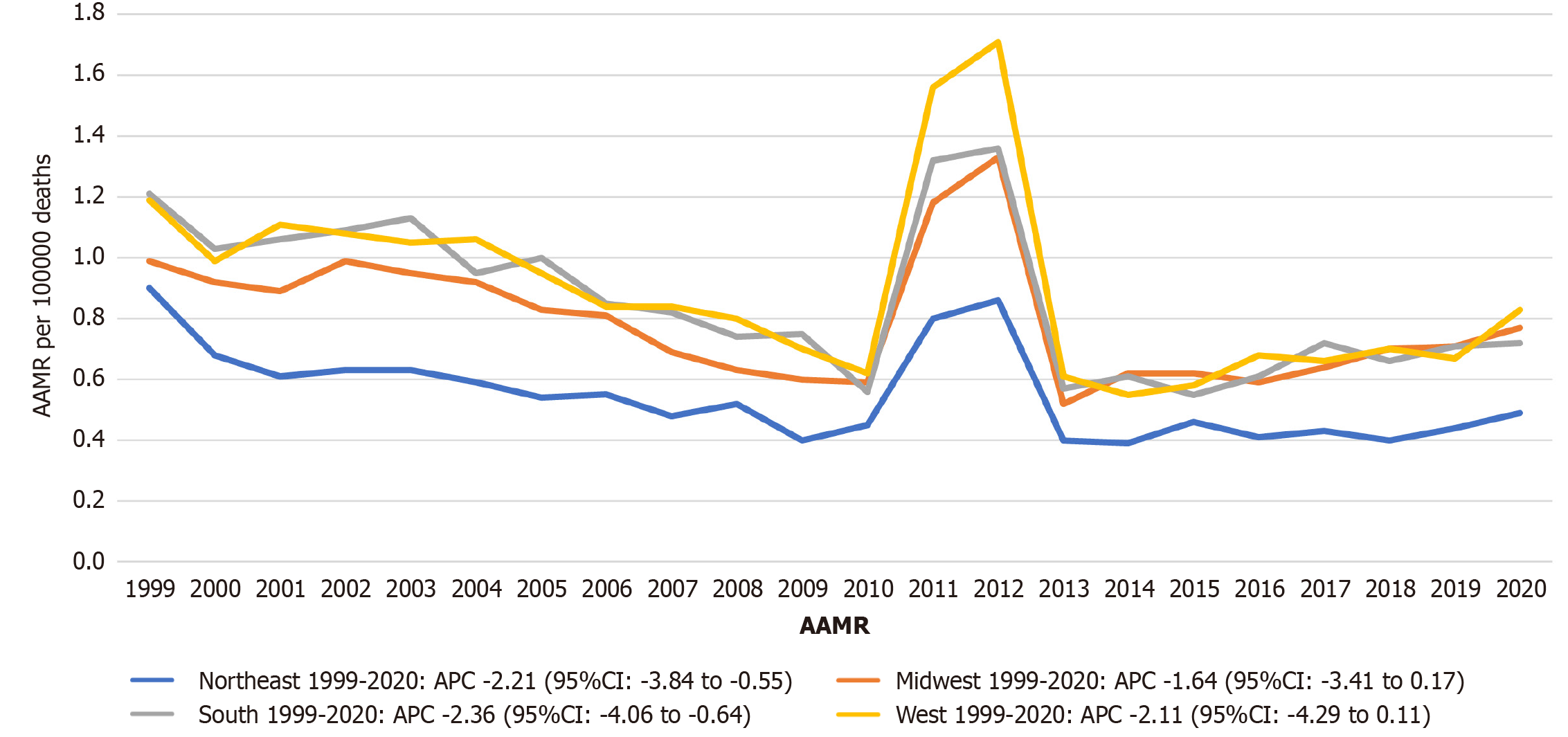

At the regional level, the West exhibited the highest overall AAMR (0.89; 95%CI: 0.87-0.90), followed by the South (0.84; 95%CI: 0.82-0.85), Midwest (0.81; 95%CI: 0.80-0.83), and Northeast (0.53; 95%CI: 0.52-0.54). Statistically significant declining trends occurred in the Northeast (APC: -2.21; 95%CI: -3.84 to -0.55) and South (APC: -2.36; 95%CI: -4.06 to -0.64). The Midwest and West showed non-significant downward trends (Midwest APC: -1.64, 95%CI: -3.41 to 0.17; West APC:

AAMRs for stroke among individuals with CKD varied by urbanization level. The highest AAMR was observed in Small Metropolitan areas at 0.87 per 100000 population (95%CI: 0.84-0.90), followed by Micropolitan (Nonmetro) areas (0.85; 95%CI: 0.82-0.88), NonCore (Nonmetro) areas (0.83; 95%CI: 0.80-0.85), Medium Metro areas (0.82; 95%CI: 0.81-0.84), Large Central Metro areas (0.81; 95%CI: 0.80-0.83), and Large Fringe Metro areas (0.64; 95%CI: 0.62-0.65). Statistically significant declining trends occurred in Large Central Metro areas (APC: -2.54; 95%CI: -4.49 to -0.55), Large Fringe Metro areas (APC: -2.26; 95%CI: -3.85 to -0.65), and NonCore (Nonmetro) areas (APC: -1.58; 95%CI: -3.09 to -0.05). Non-significant downward trends were observed in Medium Metro (APC: -1.65; 95%CI: -3.48 to 0.22), Small Metro (APC: -1.80; 95%CI:

Among the 37308 recorded stroke-related deaths among individuals with CKD, the majority (52.78%) occurred in medical facilities where the decedent was an inpatient. Nursing homes and long-term care settings accounted for 24.58% of deaths, while 11.35% occurred at home. Hospice facilities were the site of 5.05% of deaths. Outpatient and emergency department settings contributed to 2.68% of cases, and a small number were either dead on arrival (0.17%) or died in medical facilities with an unknown status (0.14%). Additionally, 3.00% of deaths occurred in other locations, and in 0.25% of cases, the place of death was not specified (Supplementary Table 8).

Our nationwide analysis of 22-year stroke mortality trends among United States adults with CKD reveals both encouraging improvements and persistent challenges. The overall decline in AAMR from 1.08 to 0.71 per 100000 between 1999 and 2020 aligns with broader cerebrovascular mortality reductions observed in the general population during this period[13]. This trend likely reflects advancements in hypertension management, statin utilization, and smoking cessation initiatives that began in the late 1990s[14]. However, our stratified analyses reveal that these benefits have been unequally distributed, with concerning disparities persisting across demographic and geographic dimensions.

The accelerated mortality reduction between 1999 and 2009 (APC: -4.25; 95%CI: -5.43 to -3.06) coincides with national quality improvement initiatives targeting cardiovascular risk factors, including widespread implementation of the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines[15]. However, subsequent fluctuations—including a significant increase from 2009 to 2012 (APC: 23.25; 95%CI: 1.24-50.05), a sharp decline from 2012 to 2015 (APC: -28.10; 95%CI: -44.14 to -7.46), and a renewed increase from 2015 to 2020 (APC: 8.72; 95%CI: 3.66-14.04)—suggest complex underlying dynamics. These may reflect competing influences such as the rising prevalence of diabetes[16], obesity[17], and evolving therapeutic limitations specific to CKD, including altered drug metabolism, accelerated atherosclerosis, and the complexities of anticoagulation[18].

Standard stroke prevention protocols may underperform in CKD populations due to pathophysiological differences like uremia-induced platelet dysfunction[19]. Furthermore, ongoing debates regarding optimal blood pressure targets in CKD continue to complicate risk management[20].

Gender disparities remained persistent, with males consistently exhibiting higher stroke-related mortality than females throughout the study period (AAMR: 0.79 vs 0.71 per 100000). Notably, both genders experienced significant declines—males (APC: -1.89; 95%CI: -3.60 to -0.15) and females (APC: -2.26; 95%CI: -4.21 to -0.27)—but without any joinpoints, indicating consistent monotonic trends. These findings mirror broader stroke epidemiology patterns[21] yet highlight unique barriers in CKD, such as delayed care engagement and lower transplant access for males[22].

Racial disparities were stark. Black or African American individuals exhibited the highest overall AAMR (1.95 per 100000; 95%CI: 1.91-2.00), nearly three times that of White individuals (0.63; 95%CI: 0.63-0.64). Despite a significant declining trend among Black individuals (APC: -4.43; 95%CI: -5.93 to -2.91), the absolute burden remains disproportionately high. Similarly, Hispanic or Latino individuals and Asian or Pacific Islander individuals showed significant overall declines (APC: -4.49 and -3.66, respectively), but experienced concerning fluctuations after 2009—including sharp increases and decreases—possibly indicating instability in access to preventive care and stroke services. These patterns reflect structural inequities in access to neurology-nephrology co-management[23,24], medication affordability[25], and underutilization of renal replacement therapy among minority populations[26].

Geographic variation was profound. The highest AAMRs occurred in the District of Columbia (1.27), South Carolina (1.24), and West Virginia (1.17), while the lowest were in Arizona (0.38) and New York (0.40). The 3.3-fold state-level disparity underscores the intersection of the "Stroke Belt" phenomenon[27] with regional gaps in nephrology workforce and quality of care[28,29]. Regional analysis revealed that the West (AAMR: 0.89) and South (0.84) bore the greatest burden, while the Northeast had the lowest AAMR (0.53) and exhibited a statistically significant decline (APC: -2.21; 95%CI: -3.84 to -0.55). These findings underscore the importance of location-specific stroke prevention and CKD management initiatives.

Urbanization-stratified analysis revealed that Small Metropolitan (AAMR: 0.87) and Micropolitan areas (0.85) had the highest burden, while Large Fringe Metro areas (0.64) had the lowest. Declining trends were significant in Large Central Metro (APC: -2.54), Large Fringe Metro (-2.26), and Noncore rural areas (-1.58), suggesting that improvements are occurring but not uniformly. The higher AAMRs in more urbanized areas may reflect pollution-related vascular risks[30], noise exposure[31], and comorbidity clustering. Meanwhile, rural areas face reduced access to stroke centers and subspecialty care[32,33].

Place of death patterns provide further insight into healthcare delivery. Over half of the deaths (52.78%) occurred in inpatient settings, while long-term care facilities accounted for nearly a quarter (24.58%). Notably, 11.35% of deaths occurred at home and 5.05% in hospice settings—indicating potential gaps in access to timely acute stroke intervention and appropriate end-of-life care planning. The relatively small proportion of deaths occurring in outpatient or emergency settings (2.68%) may point to under recognition or delayed care-seeking behaviors in this population.

Together, these findings highlight the need for three paradigm-shifting approaches. First, risk stratification should incorporate CKD-specific biomarkers—such as albuminuria progression and fibroblast growth factor-23 levels[34]—alongside traditional cardiovascular tools. Second, targeted disparity-reduction interventions are crucial: Community screening programs in high-burden regions, telehealth hypertension management in rural areas[35], and culturally co-developed educational initiatives for Black communities[36]. Third, integrative care models must embed neurologists in nephrology clinics, with standardized atrial fibrillation screening and individualized antithrombotic protocols tailored to CKD-specific bleeding risks[37,38].

Study limitations must be acknowledged. Death certificate data may underestimate CKD as a contributing cause[39] and lack granularity on disease stage or stroke subtype. Our inability to isolate dialysis-dependent individuals likely underrepresents a high-risk group with unique stroke mechanisms[40]. Moreover, potential confounding by unmeasured factors such as socioeconomic status and medication adherence remains a concern. Future research should employ linked registry data evaluate CKD-specific stroke biomarkers[41], and test community-based interventions in high-disparity settings[42].

In conclusion, while stroke mortality has declined among CKD patients since 1999, profound disparities persist across racial, gender, and geographic lines. These inequities demand precision public health approaches that move beyond uniform interventions to address region-specific, race-specific, and place-specific determinants of cerebrovascular risk. CKD must be reconceptualized not merely as a comorbidity but as a cerebrovascular risk multiplier requiring integrated nephrology-neurology care models.

This study has several limitations. Its retrospective nature restricts our ability to control for data accuracy and may introduce bias associated with the use of existing administrative records. Dependence on ICD coding for identifying stroke and CKD could result in misclassification or underreporting, and temporal changes in coding practices may affect the consistency of observed trends. Additionally, the lack of granular clinical information, such as CKD stage, duration, or treatment limits the depth of clinical interpretation. Important variables such as socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and access to healthcare were not captured, potentially introducing unmeasured confounding. Furthermore, as this is an observational study, causal relationships cannot be established. Variability in healthcare practices across regions may also affect the generalizability of our findings.

Over the 22-year period from 1999 to 2020, stroke-related mortality among individuals with CKD demonstrated an overall decline in AAMRs, reflecting potential improvements in preventive care, clinical management, and public health strategies. This downward trend was most pronounced between 1999-2008 and 2011-2020, though short periods of non-significant increases were also noted.

Despite these encouraging trends, important disparities persist. Mortality rates remained higher among males, non-Hispanic Black individuals, and residents of southern United States. Additionally, urban-rural and regional differences were evident, with higher AAMRs observed in central metropolitan areas and southern regions. Gender- and race-specific patterns revealed unique temporal variations, underscoring the influence of demographic and social determinants on health outcomes.

The findings highlight the need for targeted public health efforts to address these persistent disparities. Future research should focus on identifying the underlying biological, structural, and systemic factors contributing to these differences and evaluating interventions aimed at reducing stroke mortality among CKD populations. Enhanced surveillance, equitable access to care, and culturally informed prevention strategies will be critical to advancing health equity in this high-risk group.

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Raheel Ahmed, MBBS, MRCP, PhD (Imperial College London, United Kingdom) for his professional English language editing and refinement of the manuscript to meet international academic publication standards (Grade A). The authors also acknowledge Dr. Bilal Ahmed, MBBS, Mph, PhD (Biostatistics) for his expert review and verification of the statistical analyses and methodologies employed in this study.

| 1. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2023. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2023. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/kidney-disease/php/data-research/index.html. |

| 2. | Imoisili OE, Chung A, Tong X, Hayes DK, Loustalot F. Prevalence of Stroke - Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2011-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:449-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kourtidou C, Tziomalos K. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Stroke in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7995] [Cited by in RCA: 8697] [Article Influence: 395.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 5. | Seliger SL, Gillen DL, Longstreth WT Jr, Kestenbaum B, Stehman-Breen CO. Elevated risk of stroke among patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2003;64:603-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Curhan GC. Epidemiology of anemia associated with chronic renal insufficiency among adults in the United States: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:504-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kovesdy CP, Norris KC, Boulware LE, Lu JL, Ma JZ, Streja E, Molnar MZ, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of Race With Mortality and Cardiovascular Events in a Large Cohort of US Veterans. Circulation. 2015;132:1538-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kobo O, Abramov D, Davies S, Ahmed SB, Sun LY, Mieres JH, Parwani P, Siudak Z, Van Spall HGC, Mamas MA. CKD-Associated Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States: Temporal Trends From 1999 to 2020. Kidney Med. 2023;5:100597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, McClure LA, Safford MM, Rhodes JD, Cushman M, Moy CS, Soliman EZ, Kissela BM, Howard G. Disparities in stroke incidence contributing to disparities in stroke mortality. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:619-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER. [cited 7 July 2024] Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov. |

| 11. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5754] [Cited by in RCA: 11738] [Article Influence: 652.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Cheng S, Delling FN, Elkind MSV, Evenson KR, Ferguson JF, Gupta DK, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Lee CD, Lewis TT, Liu J, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Ma J, Mackey J, Martin SS, Matchar DB, Mussolino ME, Navaneethan SD, Perak AM, Roth GA, Samad Z, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Shay CM, Stokes A, VanWagner LB, Wang NY, Tsao CW; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e254-e743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3854] [Cited by in RCA: 3880] [Article Influence: 776.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988-2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043-2050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1412] [Cited by in RCA: 1453] [Article Influence: 90.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | K/DOQI Workgroup. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:S1-153. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Chen R, Ovbiagele B, Feng W. Diabetes and Stroke: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Pharmaceuticals and Outcomes. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351:380-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Writing Group Members; Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2843] [Cited by in RCA: 3875] [Article Influence: 352.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA. Hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1833-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wattanakit K, Cushman M, Stehman-Breen C, Heckbert SR, Folsom AR. Chronic kidney disease increases risk for venous thromboembolism. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:135-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pugh D, Gallacher PJ, Dhaun N. Management of Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease. Drugs. 2019;79:365-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Reeves M, Bhatt A, Jajou P, Brown M, Lisabeth L. Sex differences in the use of intravenous rt-PA thrombolysis treatment for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2009;40:1743-1749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cobo G, Hecking M, Port FK, Exner I, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P, Carrero JJ. Sex and gender differences in chronic kidney disease: progression to end-stage renal disease and haemodialysis. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016;130:1147-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Norton JM, Moxey-Mims MM, Eggers PW, Narva AS, Star RA, Kimmel PL, Rodgers GP. Social Determinants of Racial Disparities in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:2576-2595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Henderson ML, Gordon EJ, Crews DC, Boulware LE, Segev DL. Association of Race and Ethnicity With Live Donor Kidney Transplantation in the United States From 1995 to 2014. JAMA. 2018;319:49-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ruppar TM, Dunbar-Jacob JM, Mehr DR, Lewis L, Conn VS. Medication adherence interventions among hypertensive black adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2017;35:1145-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, Armistead N, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, David-Kasdan JA, Carlson D, Fuller J, Marsh D, Conti RM. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation--clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1537-1544, 2 p preceding 1537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Howard G, Cushman M, Kissela BM, Kleindorfer DO, McClure LA, Safford MM, Rhodes JD, Soliman EZ, Moy CS, Judd SE, Howard VJ; REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Investigators. Traditional risk factors as the underlying cause of racial disparities in stroke: lessons from the half-full (empty?) glass. Stroke. 2011;42:3369-3375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bindels RJ. 2009 Homer W. Smith Award: Minerals in motion: from new ion transporters to new concepts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1263-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rodriguez RA, Sen S, Mehta K, Moody-Ayers S, Bacchetti P, O'Hare AM. Geography matters: relationships among urban residential segregation, dialysis facilities, and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:493-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA 3rd, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, Peters A, Siscovick D, Smith SC Jr, Whitsel L, Kaufman JD; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:2331-2378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4097] [Cited by in RCA: 4156] [Article Influence: 259.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Münzel T, Schmidt FP, Steven S, Herzog J, Daiber A, Sørensen M. Environmental Noise and the Cardiovascular System. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:688-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 39.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Leira EC, Hess DC, Torner JC, Adams HP Jr. Rural-urban differences in acute stroke management practices: a modifiable disparity. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:887-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Albright KC, Branas CC, Meyer BC, Matherne-Meyer DE, Zivin JA, Lyden PD, Carr BG. ACCESS: acute cerebrovascular care in emergency stroke systems. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1210-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Gutiérrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, Smith K, Lee H, Thadhani R, Jüppner H, Wolf M. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1420] [Cited by in RCA: 1324] [Article Influence: 73.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 35. | Shaw RJ, McDuffie JR, Hendrix CC, Edie A, Lindsey-Davis L, Nagi A, Kosinski AS, Williams JW Jr. Effects of nurse-managed protocols in the outpatient management of adults with chronic conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, Blyler C, Muhammad E, Handler J, Brettler J, Rashid M, Hsu B, Foxx-Drew D, Moy N, Reid AE, Elashoff RM. A Cluster-Randomized Trial of Blood-Pressure Reduction in Black Barbershops. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1291-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 54.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Go AS, Xie D, Lash JP, Rahman M, Ojo A, Teal VL, Jensvold NG, Robinson NL, Dries DL, Bazzano L, Mohler ER, Wright JT, Feldman HI; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group. Chronic kidney disease and prevalent atrial fibrillation: the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC). Am Heart J. 2010;159:1102-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hiremath S, Holden RM, Fergusson D, Zimmerman DL. Antiplatelet medications in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review of bleeding rates. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1347-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | O'Callaghan-Gordo C, Shivashankar R, Anand S, Ghosh S, Glaser J, Gupta R, Jakobsson K, Kondal D, Krishnan A, Mohan S, Mohan V, Nitsch D, P A P, Tandon N, Narayan KMV, Pearce N, Caplin B, Prabhakaran D. Prevalence of and risk factors for chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology in India: secondary data analysis of three population-based cross-sectional studies. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e023353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Saeed F, Kousar N, Qureshi K, Laurence TN. A review of risk factors for stroke in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Vasc Interv Neurol. 2009;2:126-131. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Isakova T, Xie H, Yang W, Xie D, Anderson AH, Scialla J, Wahl P, Gutiérrez OM, Steigerwalt S, He J, Schwartz S, Lo J, Ojo A, Sondheimer J, Hsu CY, Lash J, Leonard M, Kusek JW, Feldman HI, Wolf M; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA. 2011;305:2432-2439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 856] [Cited by in RCA: 808] [Article Influence: 53.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, Nieman CL, Joo JH, Lin FR, Gitlin LN, Han HR. Effects of Community-Based Health Worker Interventions to Improve Chronic Disease Management and Care Among Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:e3-e28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/