Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.112796

Revised: October 29, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 139 Days and 16.9 Hours

Hair straightening products containing formaldehyde, glycolic acid, and glyoxylic acid may be nephrotoxic, as several studies have reported acute kidney injury (AKI) induced by these chemicals.

To investigate the clinical features, complications, and treatment of AKI resulting from topical exposure to hair-straightening products.

The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO under the registration number CRD420251010513. PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus were searched from inception to April 3, 2025, for case reports and case series des

The search yielded 168 potentially relevant articles, of which six case reports and two case series met the inclusion criteria, collectively providing data on 34 patients for 36 incidents (in one case report, three AKI episodes occurred in the same patient). In 20 incidents, the hair product was identified as “formaldehyde-free”, while in 16 incidents, the chemical composition was unknown. All patients were female (mean age: 28.53 ± 11.72 years; range: 10-58 years) and the median time for the development of AKI was 2 days. The mean serum creatinine level at admission was 5.24 ± 2.83 mg/dL (range: 1.9-13.2 mg/dL). The most common presenting symptoms were vomiting (n = 29/36; 80.6%), nausea (n = 25/36; 69%), and abdominal pain (n = 13/36; 36%). Complications included one patient who developed severe dyspnea with bilateral lung infiltrates and another who developed severe hypertension and hyperkalemia. Twenty-one incidents were managed conservatively, five required steroid therapy, three required hemodialysis, and three required both hemodialysis and steroids. All patients recovered and were discharged.

The findings of this systematic review highlight the need for caution when using hair-straightening products due to their potential to cause AKI.

Core Tip: This systematic review is the first comprehensive synthesis of reported cases linking topical hair-straightening products to acute kidney injury (AKI). Analyzing 36 incidents of AKI in 34 female patients, the current study highlights that topical application of hair straightening chemicals can trigger AKI through mechanisms involving calcium oxalate ne

- Citation: Aamir AB, Latif R, Sorath F, Chander S, Latif A, Rahaman Z, Mohammed YN, Parkash O, Devi P, Hassan GA, Alalwan BM. Acute kidney injury induced by topical hair straightening products: A systematic review. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 112796

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/112796.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.112796

Several studies have documented the detrimental effects of occupational (occurring in the workplace as part of one’s job duties), cosmetic (personal treatments for beautifying purposes), or intentional (deliberate ingestion, inhalation to self-harm or poisoning attempts) exposure to hair products such as paraphenylenediamine-containing hair dyes on kidney function over the past two decades[1-5]. Previous investigations have also indicated that formaldehyde-based hair-straightening products may induce acute kidney injury (AKI)[6,7]. Given the substantial evidence from animal studies demonstrating formaldehyde-induced nephrotoxicity[8-11], formaldehyde in hair-straightening formulations was replaced with C2 carboxylic acids, such as glycolic and glyoxylic acids, under the assumption that these compounds represented safer alternatives[12]. These formulations are marketed as “formaldehyde-free” hair-straightening products[13].

However, emerging evidence suggests that formaldehyde-free hair-straightening products may also be associated with AKI[7,13-15]. The use of these products has been linked to biopsy-confirmed acute tubulointerstitial nephritis[16,17], tubular necrosis[18], and inflammatory changes within the renal tubules[19,20]. Additional studies have reported potential pulmonary[21] and developmental toxicity[22] following respiratory or oral exposure to these formulations. Although the precise mechanisms underlying the nephrotoxicity of formaldehyde-free products remain under investigation, preliminary experimental studies in animals suggest that topical exposure may induce hyperoxaluria and calcium oxalate nephropathy[23-25]. Moreover, multiple case reports have documented oxalate crystal deposition within the renal tubules of affected individuals[15,19,20].

Notably, glycolic acid-the principal active constituent of formaldehyde-free hair-straightening products-has been shown to release formaldehyde when exposed to high temperatures, such as during blow-drying or flat-ironing. The released formaldehyde can be inhaled or absorbed through the scalp, resulting in systemic exposure and potential nephrotoxicity[13]. The straightening procedure typically involves the topical application of the product followed by high heat exposure (flat iron temperatures often exceeding 150-200 °C in salon practice), a combination that facilitates the thermal release of formaldehyde and increases both inhalation and dermal absorption. Poor salon ventilation and repeated procedures further contribute to cumulative exposure. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to investigate the clinical features, complications, and management of AKI resulting from topical exposure to hair-straightening products.

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement[26]. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO under the registration number CRD420251010513 (available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251010513).

A comprehensive search strategy was developed to identify relevant studies from three electronic databases-PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus, from their inception to April 3, 2025. The search combined terms and themes related to AKI and hair straightening chemicals as follows: Theme 1: “AKI” OR “acute kidney failure” OR “acute kidney insufficiency” OR “acute kidney damage” OR “acute renal injury” OR “acute renal failure” OR “acute renal insufficiency” OR “Acute renal damage” OR “Nephropathy”. Theme 2: “Hair straighteners” OR “Hair straightening chemicals” OR “Hair straightening products” OR “Hair relaxers” OR “Hair relaxing chemicals” OR “Hair relaxing products” OR “Keratin hair treatment” OR “Formaldehyde free” OR “Formaldehyde-free” OR “Glycolic acid” OR “Glyoxylic acid”. In addition, the bibliography of relevant articles was also searched manually. The detailed search strategy is described in Supplementary Table 1.

Study screening and selection were conducted in three stages: Deduplication, title and abstract screening, and full-text review. The Zotero application was used for deduplication. Articles published in English or in other languages with an English abstract were considered for inclusion, following the patient/population, intervention, comparison and outcomes framework as outlined below: Population: Human participants. Intervention: Topical hair straightening products. Comparator: None. Outcome: Clinical features, complications, and management.

Case reports, case series, or letters to the editor describing patient presentations. AKI was defined as an abrupt decline in renal function within 48 hours, according to the AKI Network criteria[27]. AKI was considered hair-straightening-induced when alternative causes were excluded through clinical, laboratory, and imaging evaluations, and symptoms developed within 48-72 hours of chemical exposure[19]. In cases where a single patient experienced multiple AKI epi

Study quality was assessed independently by two authors using a standardized tool adapted from Murad et al[28]. This tool has been previously applied in systematic reviews of case reports[29]. It comprises four items, each rated with a binary response to indicate the potential presence of bias. The overall quality of each study was classified as “good”, “moderate”, or “poor” corresponding to a low, moderate, or high risk of bias, respectively, in accordance with the criteria of Smith et al[29]. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus following consultation with the senior author.

Data were extracted using a standardized template and included: (1) Patient demographics (patient age and gender) and study characteristics (country and year of publication); (2) Comorbidities; (3) Clinical features of the illness; (4) Diagnostic findings; (5) Management modalities; and (6) Clinical outcomes.

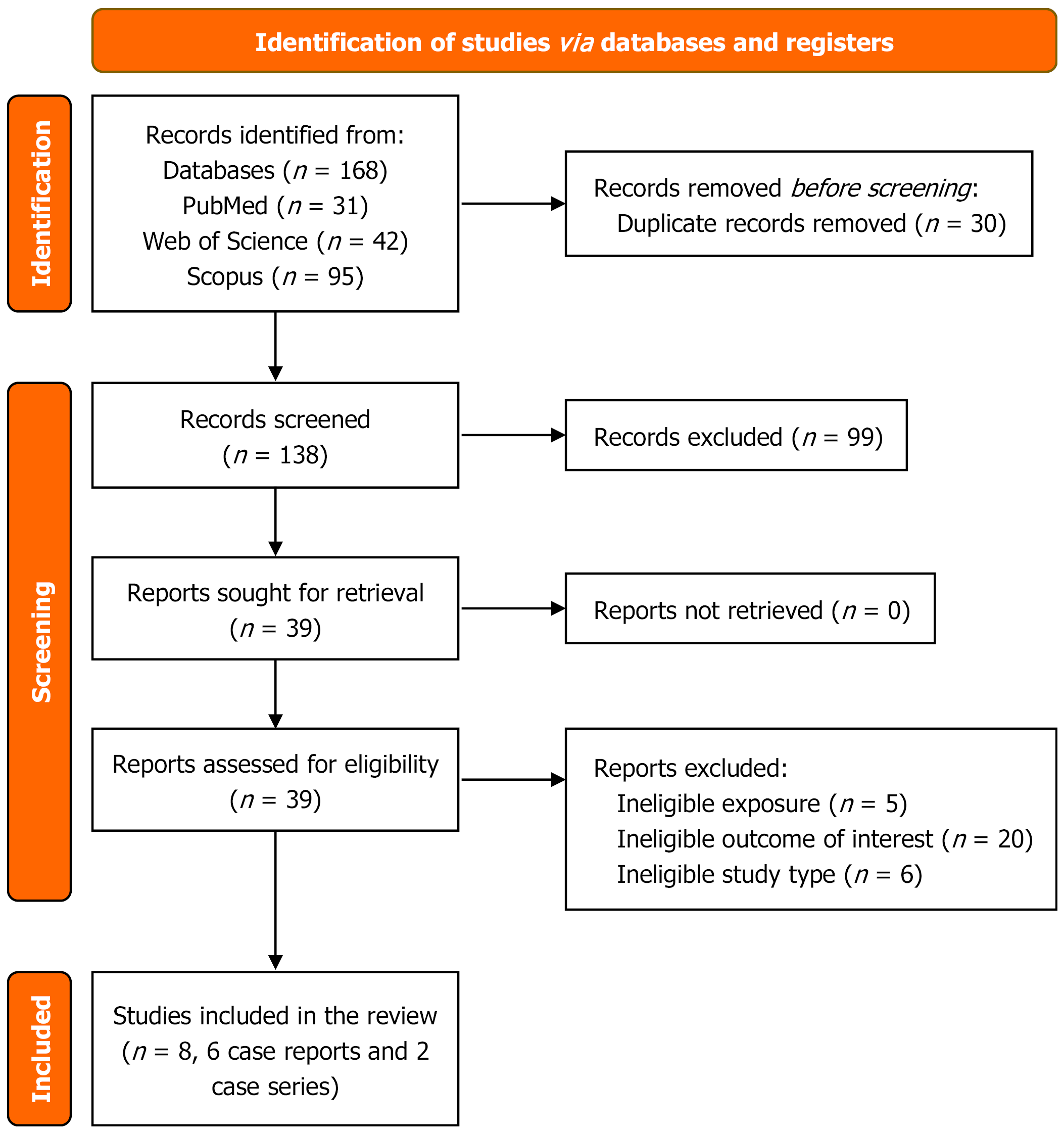

The search strategy yielded 168 potentially relevant articles from PubMed (n = 31), Web of Science (n = 42), and Scopus (n = 95). After removing 30 duplicates, 138 articles remained for title and abstract screening (Figure 1). Of these, 39 articles were deemed eligible for full-text review. Ultimately, six case reports and two case series met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review.

The six reports of individual cases and two case series provided data on a total of 34 patients (Table 1). The individual cases originated from the United Arab Emirates, Switzerland, France, and Algeria (one each), and Israel (two reports). Case series were published from Israel (one series comprising 26 patients) and Egypt (one series comprising two pa

| Ref. | Study type | Patient’s age/gender | Comorbidities | Clinical features | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | Renal sonography | Renal biopsy | Treatment | Outcome | Hair straightening method |

| Abu-Amer et al[20], 2022 | Case report | 41/F | Hypothyroidism, sleeve gastrectomy | Weakness, nausea, vomiting | 3.46 | Yes | Yes | Prednisolone 1 mg/kg | Recovered. creatinine 0.9 after one week | Formaldehyde-free product |

| Bashir and Khater[16], 2023 | Case report | 40/F | Hypothyroidism | Scalp rash, hypertension, hyperkalemia | 3.5 | No | Yes | Pulse steroids | Recovered. Creatinine 0.9 at 4-month follow-up | Formaldehyde-free product |

| Huber et al[15], 2024 | Case report | 42/F | Healthy | Weakness, nausea, vomiting, flank pain, diarrhea, flank tenderness, hypertension | 6.61 | Yes | Yes | Conservative management | Recovered. Creatinine 0.87 at 3-month follow-up | Unknown |

| Mitler et al[18], 2021 | Case report | 13/F | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, oliguria, tachycardia, hypertension, dehydration, abdominal tenderness | 3.56 | Yes | Yes | Hemodialysis for four consecutive days | Recovered. Creatinine normalized 6-month follow-up | Formaldehyde-free product |

| Robert et al[41], 2024 | Case report incidence 1 | 26/F | Healthy | Scalp burning sensation, scalp ulcers, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, back pain | 2.1 | Yes | No | Unknown | Recovered. Serum creatinine returned to normal (0.78) at the last follow-up | Containing 10% glyoxylic acid but no glycolic acid |

| Incidence 2 | 25/F | Scalp burning sensation, scalp ulcers, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, back pain | 2.4 | Yes | No | Unknown | Recovered. Serum creatinine returned to normal (0.78) at the last follow-up | Formaldehyde-free product (containing 10% glyoxylic acid but no glycolic acid) | ||

| Incidence 3 | 24/F | Scalp burning sensation, scalp ulcers, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, back pain | 1.9 | Yes | No | Unknown | Recovered. Serum creatinine returned to normal (0.78) at the last follow-up | Formaldehyde-free product (containing 10% glyoxylic acid but no glycolic acid) | ||

| Zergui et al[14], 2025 | Case report | 25/F | Nausea, vomiting, weakness | 3.2 | Yes | No | Saline, calcium gluconate, insulin, 25 g glucose, sodium bicarbonate | Recovered. Serum creatinine returned to 1.2 at the two-week follow-up | Formaldehyde-free product (contained glyoxylic acid) | |

| Ahmed et al[17], 2019 | Case series of 2 cases case 1 | 10/F | Healthy | Vomiting, tachycardia, dyspnea, hypertension, scalp rash | 13.2 | Yes | Yes | Hemodialysis for three consecutive days; 20 mg/kg/dose methylprednisolone for three days followed by oral prednisone (60 mg/m2/day) | Recovered. Discharged with improved RFTs | Formaldehyde-free product |

| Case 2 | 17/F | Healthy | Vomiting, syncope, scalp rash | 9.9 | Yes | Yes | Hemodialysis for three consecutive days; corticosteroids 40 mg/day | Recovered. Discharged with normal RFTs | Formaldehyde-free product | |

| Bnaya et al[19], 20231 | Case series of 26 cases case 1 | 24/F | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea | 5.82 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown |

| Case 2 | 22/F | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, scalp rash | 2.76 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 3 | 30/F | Nephrolithiasis | Nausea, vomiting, scalp rash, flank pain | 4.81 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 4 | 29/F | Healthy | Nausea, vomiting, scalp rash | 2.09 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 5 | 21/F | Epilepsy | Abdominal pain, vomiting, scalp rash, headache | 11.83 | No | Yes | Steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 6 | 58/F | Healthy | Nausea, flank pain, syncope | 7.54 | No | Yes | Steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 7 | 14/F | Healthy | Nausea, flank pain, headache | 3.8 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 8 | 31/F | Healthy, smoking | Abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea | 8.14 | No | No | Temporary hemodialysis | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 9 | 29/F | Nephrolithiasis | Vomiting, scalp rash | 6.8 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 10 | 52/F | Psoriasis, nephrolithiasis | Abdominal pain, flank pain, nausea, vomiting | 3.4 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 11 | 24/F | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea, fever | 2.17 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 12 | 33/F | Healthy | Nausea, vomiting, chills | 6 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 13 | 13/F | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | 3.56 | No | Yes | Temporary hemodialysis | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 14 | 17/F | Psoriasis | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | 7.1 | No | Yes | Temporary hemodialysis and steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 15 | 17.5/F | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, scalp rash | 2.9 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 16 | 24/F | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, scalp rash | 4.2 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 17 | 36/F | Healthy | Nausea, vomiting, scalp rash | 6 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 18 | 21/F | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | 3.2 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 19 | 41/F | Hypothyroidism, sleeve gastrectomy | Nausea, vomiting | 3.46 | No | Yes | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 20 | 19/F | Healthy | Nausea, flank pain, headache | 5.09 | No | Yes | Steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 21 | 44/F | Hypercoagulability state (prothrombin variant) | Vomiting, flank pain | 7.8 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 22 | 50/F | Healthy | Nausea, vomiting | 7.3 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown | |

| Case 23 | 21/F | Healthy | Nausea, vomiting, flank pain, scalp rash | 3.68 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 24 | 28/F | Atopic dermatitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease | Nausea, vomiting, flank pain, scalp rash | 2.83 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 25 | 32/F | Healthy | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | 9.03 | No | Yes | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Formaldehyde-free product (containing glycolic acid) | |

| Case 26 | 30/F | Healthy | Flank pain | 7.36 | No | No | No KRT, no steroids | Recovered | Unknown |

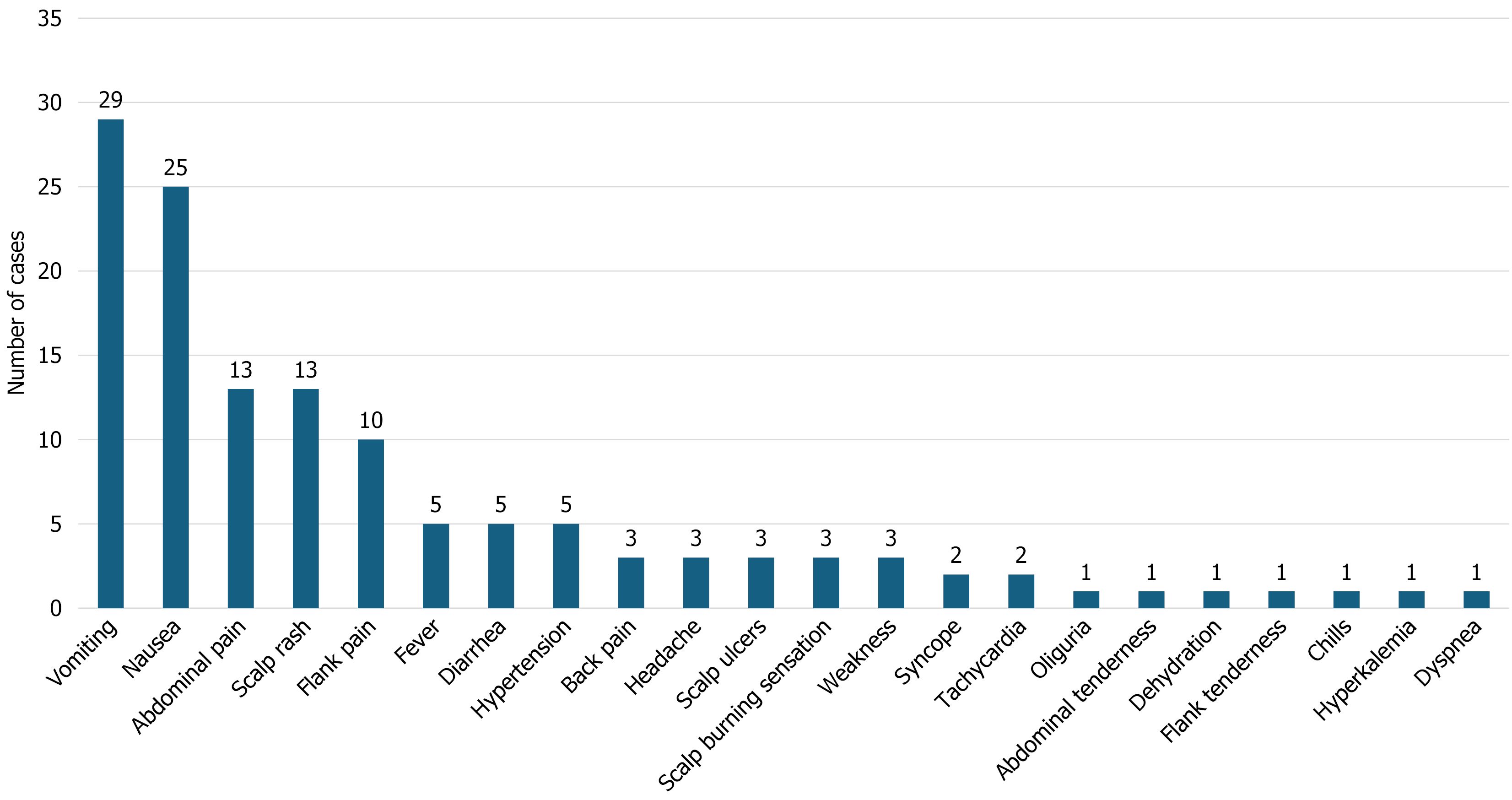

A total of 36 episodes of AKI occurred in 34 patients, as some experienced more than one episode. The mean age of the patients was 28.53 ± 11.72 years (range: 10-58; < 20 years: n = 8; ≥ 20 years: n = 28). The mean serum creatinine level at admission was 5.29 ± 2.85 mg/dL (range 1.9-13.2 mg/dL). All patients were hemodynamically stable. The most common presenting symptom was vomiting (n = 29/36; 80.6%), followed by nausea (n = 25/36; 69%), abdominal pain (n = 13/36; 36%), scalp rash (n = 13/36; 36%), and flank pain (n = 10/36; 28%) (Figure 2). Less commonly reported symptoms included oliguria, abdominal tenderness, dehydration, flank tenderness, chills, dyspnea, and hyperkalemia (each reported in 2.8% of cases).

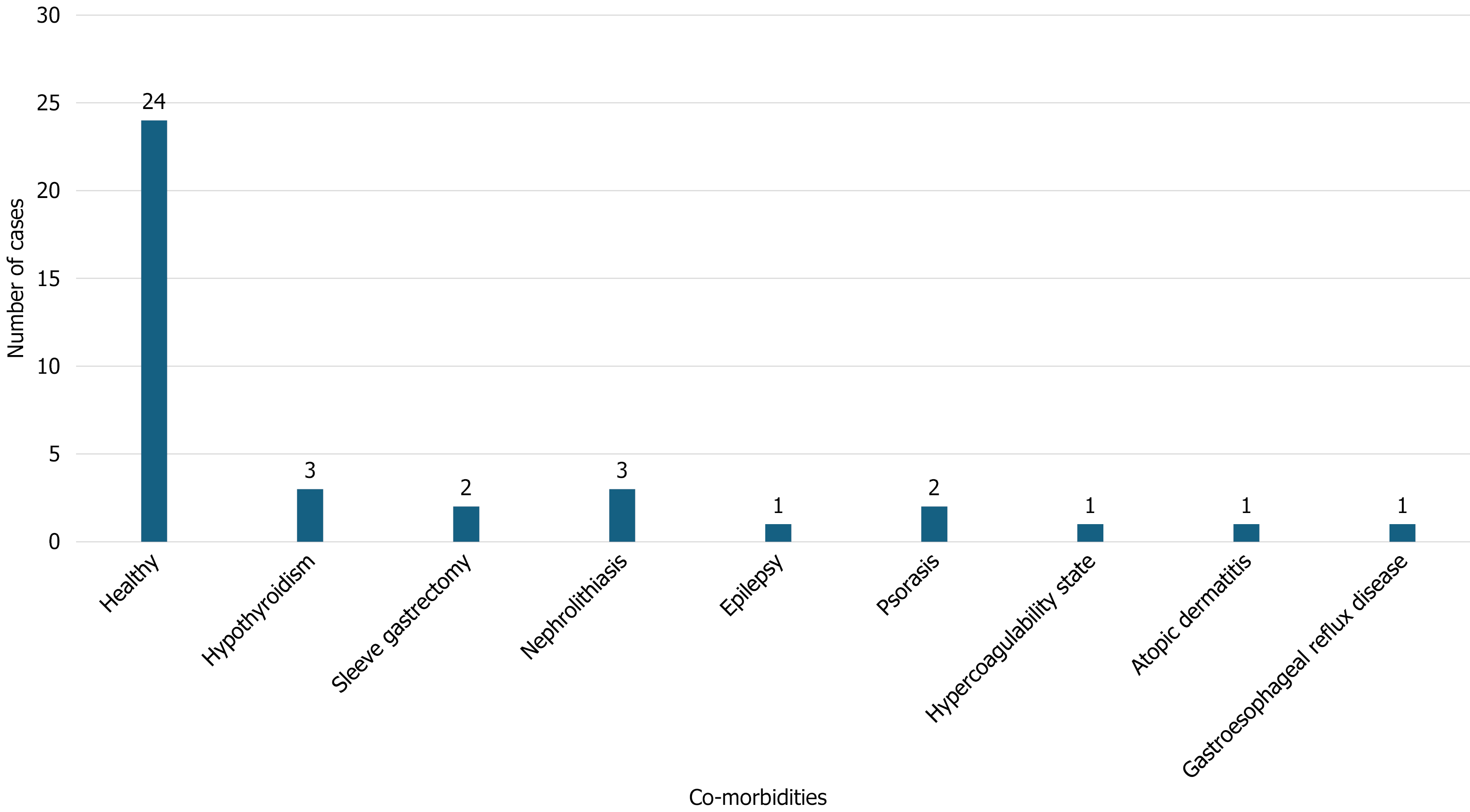

In most cases (n = 24/36; 66.7%), patients were previously healthy with no comorbidities (Figure 3). Among those with pre-existing conditions, three patients had hypothyroidism (8.3%), three had a history of nephrolithiasis (8.3%), two had psoriasis (5.6%), one had atopic dermatitis (2.8%), and one had epilepsy (2.8%). The hair-straightening products used were identified as “formaldehyde-free” in 20 incidents, while the chemical nature was unknown in 16 incidents (Table 1).

In the study by Bnaya et al[19], one patient developed severe dyspnea with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, whereas the patient described by Bashir and Khater[16] presented with severe hypertension and hyperkalemia. Both patients subsequently achieved full clinical recovery.

All cases met the diagnostic criteria for AKI (i.e., a rise in serum creatinine ≥ 0.3 mg/dL). The mean serum creatinine level at admission was 5.24 ± 2.83 mg/dL (range: 1.9-13.2 mg/dL) (Table 1). All cases fulfilled the criteria for hair-straigh

| Ref. | Sonography findings |

| Abu-Amer et al[20], 2022 | 14.4-cm bilateral echogenic, edematous renal parenchyma |

| Huber et al[15], 2024 | Normal kidneys with slight corticomedullary dedifferentiation, absence of pyelocaliceal dilation, and normal vascular flow |

| Mitler et al[18], 2021 | 15-cm edematous renal parenchyma |

| Robert et al[41], 2024 (3 incidents in the same patient) | No evidence of obstructive uropathy |

| Zergui et al[14], 2025 | Normal-sized kidneys; findings consistent with acute kidney injury of non-obstructive etiology |

| Ahmed et al[17], 2019 (case 1) | Bilateral grade 1 nephropathy |

| Ahmed et al[17], 2019 (case 2) | Bilateral grade 1 nephropathy |

| Ref. | Microscopic findings |

| Abu-Amer et al[20], 2022 | The biopsy demonstrated features of both oxalate nephropathy and interstitial nephritis (intratubular oxalate crystals, interstitial edema, mixed inflammatory infiltrates with eosinophils, and foci of tubulitis) |

| Bashir and Khater[16], 2023 | Acute interstitial nephritis |

| Huber et al[15], 2024 | Findings were consistent with oxalate nephropathy rather than interstitial nephritis (numerous intratubular calcium oxalate crystal deposits and mild interstitial edema without inflammatory infiltrates) |

| Mitler et al[18], 2021 | Oxalate nephropathy (microcalcifications/calcium oxalate crystals) |

| Ahmed et al[17], 2019 (case 1) | Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis |

| Ahmed et al[17], 2019 (case 2) | Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis |

| Bnaya et al[19], 2023 (case 5) | The biopsy demonstrated features of both oxalate nephropathy and interstitial nephritis (calcium oxalate crystals, small mononuclear interstitial infiltrate with spare eosinophils) |

| Bnaya et al[19], 2023 (case 6) | The biopsy demonstrated features of both oxalate nephropathy and interstitial nephritis (oxalate crystals, small mononuclear interstitial infiltrate) |

| Bnaya et al[19], 2023 (case 13) | The biopsy demonstrated oxalate nephropathy (microcalcifications/calcium oxalate crystals) |

| Bnaya et al[19], 2023 (case 14) | Oxalate nephropathy |

| Bnaya et al[19], 2023 (case 19) | The biopsy demonstrated features of both oxalate nephropathy and interstitial nephritis (oxalate crystals, multifocal mixed inflammatory infiltrates with multiple eosinophils) |

| Bnaya et al[19], 2023 (case 20) | Findings were consistent with oxalate nephropathy rather than interstitial nephritis (calcium oxalate crystals; interstitium with mild edema and sparse eosinophils) |

| Bnaya et al[19], 2023 (case 25) | Oxalate nephropathy |

Of the 36 AKI incidents, five were treated with steroids alone, three with hemodialysis alone, and three with he

All case reports and case series included in this review were determined to have a low risk of bias and were rated as high quality (Table 4).

| Ref. | Was the exposure (hair-straightening products) adequately ascertained?1 | Was the outcome (AKI) adequately ascertained?2 | Were other alternative causes that may explain the outcome (AKI) ruled out?3 | Were all important data cited?4 | Risk of bias5 |

| Abu-Amer et al[20], 2022 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Bashir and Khater[16], 2023 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Huber et al[15], 2024 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Mitler et al[18], 2021 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Robert et al[41], 2024 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Zergui et al[14], 2025 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Ahmed et al[17], 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Bnaya et al[19], 2023 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

This systematic review indicates that although typically non-fatal, topical hair straightening products can cause AKI even in otherwise healthy individuals. Fewer than 10% of the patients had a history of hypothyroidism or nephrolithiasis; however, it remains unclear whether these comorbidities represent risk factors for hair straightening-induced AKI. Among the 36 AKI incidents included in our analysis, only 2 (6%) were associated with severe complications.

In addition, tubular presence of oxalate crystals was noted in 10 out of the 13 cases (77%) in our study population for whom renal biopsy results were available. Furthermore, 70%-80% of the patients presented with nausea and vomiting, which are typical symptoms of oxalate nephrolithiasis[30]. This supports the hypothesis that renal toxicity of hair-straigh

Given that 23% of the patients in our study population with renal biopsy findings presented with AKI without evidence of oxalate crystal formation, it is likely that additional factors contribute to the pathogenesis of hair-straigh

The hypothesis that oxalate nephropathy and inflammation contribute to the development of AKI following the use of hair-straightening products is further supported by the clinical outcomes of the patients included in this systematic review. All patients recovered and were successfully discharged. Most (27/36; 75%) were managed conservatively, a few required KRT (6/36; 16.7%) and treatment details were not reported for 8.3% of cases (3/36). While KRT is a common therapeutic measure for AKI, steroids are rarely used[38].

Although the current systematic review is the largest and most up-to-date effort to examine the clinical presentation, complications, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of patients with AKI induced by hair-straightening products, it has several important limitations. Our data synthesis relied entirely on case reports and series, and the absence of rando

The findings of this systematic review highlight the need for caution when using hair-straightening products, particularly among individuals at risk of AKI. Clinicians should also consider AKI in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting to the emergency department shortly after exposure to hair-straightening products. Moreover, these products should be recognized as a potential etiological factor in cases of unexplained AKI among frequent users. As heat may trigger the release of formaldehyde from so-called formaldehyde-free formulations; reducing flat-iron temperatures and shortening the duration of heat application may decrease the amount of formaldehyde generated. Finally, the establishment of prospective monitoring systems or product safety registries is warranted to generate robust evidence that can better inform regulatory decision-making and enhance public awareness regarding the potential risks associated with hair-straightening product use.

| 1. | Ramulu P, Rao PA, K K, K P, Devi CVR. A prospective study on clinical profile and incidence of acute kidney injury due to hair dye poisoning. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:5277-5282. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Sampathkumar K, Yesudas S. Hair dye poisoning and the developing world. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2009;2:129-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hamdouk M, Abdelraheem M, Taha A, Cristina D, Checherita IA, Alexandru C. The association between prolonged occupational exposure to paraphenylenediamine (hair-dye) and renal impairment. Arab J Nephrol Transplant. 2011;4:21-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kumar BJ, Kondaveeti D, Mounika G, Saraswathi P, Prasad PD, Gokul T. Case Report of a 27-year-old Patient with Hair Dye Poisoning Causing Acute Kidney Injury. J Forensic Sci Med. 2024;10:351-353. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Sandeep Reddy Y, Abbdul Nabi S, Apparao C, Srilatha C, Manjusha Y, Sri Ram Naveen P, Krishna Kishore C, Sridhar A, Siva Kumar V. Hair dye related acute kidney injury--a clinical and experimental study. Ren Fail. 2012;34:880-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Aglan MA, Mansour GN. Hair straightening products and the risk of occupational formaldehyde exposure in hairstylists. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2020;43:488-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nasri H, Razmjouei S. Renal complications of hair-straightening products; a public awareness. J Ren Endocrinol. 2025;11:e25168. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Ramos CO, Nardeli CR, Campos KKD, Pena KB, Machado DF, Bandeira ACB, Costa GP, Talvani A, Bezerra FS. The exposure to formaldehyde causes renal dysfunction, inflammation and redox imbalance in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2017;69:367-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Golalipour MJ, Azarhoush R, Ghafari S, Davarian A, Fazeli HSA. Can Formaldehyde Exposure Induce Histopathologic and Morphometric Changes on Rat Kidney? Int J Morphol. 2009;27:1195-1200. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | İnci M, Zararsız İ, Davarcı M, Görür S. Toxic effects of formaldehyde on the urinary system. Turk J Urol. 2013;39:48-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Olisah MC, Meludu SC. A Comparative Study of Serum Cystatin C, Serum Electrolytes, Urea and Creatinine in Early Detection of Kidney Injuries in Albino Rats Exposed to Formaldehyde. IPS J Tox. 2021;1:1-4. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Weathersby C, McMichael A. Brazilian keratin hair treatment: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Needle CD, Kearney CA, Brinks AL, Kakpovbia E, Olayinka J, Shapiro J, Orlow SJ, Lo Sicco KI. Safety of chemical hair relaxers: A review article. JAAD Reviews. 2024;2:50-56. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Zergui A, Kerdoun MA, Chefirat B. Acute Kidney Injury following a use of a keratin-based hair-straightening product containing glyoxylic acid: A case report. Toxicol Anal Clin. 2025;37:412-415. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Huber A, Deffert C, Moll S, de Seigneux S, Berchtold L. Acute Kidney Injury and Hair-Straightening Products. Kidney Int Rep. 2024;9:2571-2573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bashir N, Khater E. WCN23-0696 Formaldehyde- free hair product causing AKI and AIN in female patient. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:S10-S11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Ahmed HM, Rashad SH, Ismail W. Acute Kidney Injury Following Usage of Formaldehyde-Free Hair Straightening Products. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2019;13:129-131. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Mitler A, Houri S, Shriber L, Dalal I, Kaidar-Ronat M. Recent use of formaldehyde-'free' hair straightening product and severe acute kidney injury. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14:1469-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bnaya A, Abu-Amer N, Beckerman P, Volkov A, Cohen-Hagai K, Greenberg M, Ben-Chetrit S, Ben Tikva Kagan K, Goldman S, Navarro HA, Sneineh MA, Rozen-Zvi B, Borovitz Y, Tobar A, Yanay NB, Biton R, Angel-Korman A, Rappoport V, Leiba A, Bathish Y, Farber E, Kaidar-Ronat M, Schreiber L, Shashar M, Kazarski R, Chernin G, Itzkowitz E, Atrash J, Iaina NL, Efrati S, Nizri E, Lurie Y, Ben Itzhak O, Assady S, Kenig-Kozlovsky Y, Shavit L. Acute Kidney Injury and Hair-Straightening Products: A Case Series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;82:43-52.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abu-Amer N, Silberstein N, Kunin M, Mini S, Beckerman P. Acute Kidney Injury following Exposure to Formaldehyde-Free Hair-Straightening Products. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 2022;12:112-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lim SK, Yoo J, Kim H, Kim W, Shim I, Yoon BI, Kim P, DO Yu S, Eom IC. Acute and 28-Day Repeated Inhalation Toxicity Study of Glycolic Acid in Male Sprague-Dawley Rats. In Vivo. 2019;33:1507-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Munley SM, Kennedy GL, Hurtt ME. Developmental toxicity study of glycolic acid in rats. Drug Chem Toxicol. 1999;22:569-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Robert T, Tang E, Kervadec J, Desmons A, Hautem JY, Zaworski J, Daudon M, Letavernier E. Hair-straightening cosmetics containing glyoxylic acid induce crystalline nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2024;106:1117-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Maalouf NM, Whittamore JM. Oxalate nephropathy associated with glyoxylate-containing hair-straightening products: a call for caution. Kidney Int. 2024;106:1023-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Salido E, Pey AL, Rodriguez R, Lorenzo V. Primary hyperoxalurias: disorders of glyoxylate detoxification. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:1453-1464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51847] [Article Influence: 10369.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A; Acute Kidney Injury Network. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4846] [Cited by in RCA: 5067] [Article Influence: 266.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23:60-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1008] [Cited by in RCA: 1682] [Article Influence: 210.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Smith CM, Gilbert EB, Riordan PA, Helmke N, von Isenburg M, Kincaid BR, Shirey KG. COVID-19-associated psychosis: A systematic review of case reports. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;73:84-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shah A, Leslie SW, Ramakrishnan S. Hyperoxaluria. 2024 Mar 4. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Rosenstock JL, Joab TMJ, DeVita MV, Yang Y, Sharma PD, Bijol V. Oxalate nephropathy: a review. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15:194-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Llanos M, Kwon A, Herlitz L, Shafi T, Cohen S, Gebreselassie SK, Sawaf H, Bobart SA. The Clinical and Pathological Characteristics of Patients with Oxalate Nephropathy. Kidney360. 2024;5:65-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Buysschaert B, Aydin S, Morelle J, Gillion V, Jadoul M, Demoulin N. Etiologies, Clinical Features, and Outcome of Oxalate Nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:1503-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lumlertgul N, Siribamrungwong M, Jaber BL, Susantitaphong P. Secondary Oxalate Nephropathy: A Systematic Review. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3:1363-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ceonzo K, Gaynor A, Shaffer L, Kojima K, Vacanti CA, Stahl GL. Polyglycolic acid-induced inflammation: role of hydrolysis and resulting complement activation. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:301-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tang SC, Liao PY, Hung SJ, Ge JS, Chen SM, Lai JC, Hsiao YP, Yang JH. Topical application of glycolic acid suppresses the UVB induced IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1 and COX-2 inflammation by modulating NF-κB signaling pathway in keratinocytes and mice skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;86:238-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Park KS, Kim HJ, Kim EJ, Nam KT, Oh JH, Song CW, Jung HK, Kim DJ, Yun YW, Kim HS, Chung SY, Cho DH, Kim BY, Hong JT. Effect of glycolic acid on UVB-induced skin damage and inflammation in guinea pigs. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 2002;15:236-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gameiro J, Fonseca JA, Outerelo C, Lopes JA. Acute Kidney Injury: From Diagnosis to Prevention and Treatment Strategies. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 875] [Cited by in RCA: 1869] [Article Influence: 186.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Viswanathan M, Patnode CD, Berkman ND, Bass EB, Chang S, Hartling L, Murad MH, Treadwell JR, Kane RL. Recommendations for assessing the risk of bias in systematic reviews of health-care interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:26-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Robert T, Tang E, Kervadec J, Zaworski J, Daudon M, Letavernier E. Kidney Injury and Hair-Straightening Products Containing Glyoxylic Acid. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1147-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/