Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.112190

Revised: August 2, 2025

Accepted: September 18, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 156 Days and 8.9 Hours

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL) is the standard treatment for medium-sized and large kidney stones. Many potential complications of PNL may warrant hos

To estimate the rate of unplanned HR after PNL and identify its urological and nursing-related predictors.

One hundred sixty-one patients were prospectively studied for HR after PNL from April 2022 to December 2022. The relevant urological and nursing-related characteristics of patients with and without unplanned HR after PNL were stu

The mean age of patients with HR (44.4 ± 12.7 years) and without HR (43.9 ± 12.6 years) was similar (P = 0.847). The overall stone-free rate was 88.8%. The total complication rate was 32.3% (52 patients), and the highest grade was IIIa, according to the modified Clavein grading system, resulting in an HR rate of 22.4%. History of preoperative pyuria (P = 0.001), hydronephrosis (P = 0.001) and mean stone size (P = 0.012), multiple renal punctures (P < 0.001), double J stent (P = 0.033), total operative time (P = 0.001), intraoperative injury (P = 0.011), postoperative urinary tract infection (P < 0.001), and inadequate instructions for urethral catheter (P = 0.001) and activity daily living (P = 0.048) were significantly associated with HR after PNL. On multivariate analysis, only preoperative pyuria (P = 0.004), intraoperative injury (P = 0.001), and inadequate instructions on urethral catheter care (P = 0.035) were associated with HR. The risk score of the independent predictors was 0-17; 0-4 (low risk), 5-9 (moderate risk), and 10-17 (high risk).

The rate of unplanned HR after PNL was relatively high (22.4%). The presence of pus cells in the preoperative urine analysis, intraoperative injury, and receiving inadequate instructions on urethral catheter care were in

Core Tip: Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL) is the first line of treatment for large kidney stones. Although the complica

- Citation: Gadelkareem RA, Abodief HT, Azer SZ, Fawzy W, Desoky AA. Urological and nursing-related predictors of unplanned hospital readmission after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: A prospective cohort study. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 112190

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/112190.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.112190

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL) is the standard treatment for large kidney stones, measuring more than 2 cm, and lower pole stones greater than 1.5 cm[1,2]. It has many advantages and low complication rates. The latter may warrant hospital readmission (HR) in the convalescence course of patients undergoing PNL[3]. HR is commonly defined as an unscheduled readmission of a patient to a hospital within 30 days of discharge from the same or another hospital due to health problems relevant to the primary intervention[3,4]. HR is a professional and financial extra burden to the heal

In a prospective cohort study, adult patients who underwent PNL in Assiut University Urology Hospital, Assiut, Egypt, between April 2022 and December 2022 for renal stones > 2 cm were studied for the rate of unplanned HR after PNL.

For a suitable sample size calculation, our hospital records, which showed a rate of 244 cases of PNL in 2021, and the sample size in a relevant previous study from our institute were considered[13]. Accordingly, a sample size of 150 pa

The evaluation of patients included meticulous history-taking, physical examination, and surgical fitness assessment. In addition, routine laboratory investigations were performed, including urinalysis, urine culture and sensitivity test, renal function tests, complete blood count, bleeding profiles, and a random blood sugar level. Imaging workups included abdominal ultrasonography (US), plain X-ray kidney-ureter-bladder (KUB), and multi-slice NCCT for all patients.

The surgical techniques and armamentarium of PNL were based on our classic technique, which was previously described[5]. On postoperative day one, KUB and US were performed. With the absence of residual stones, the ne

The primary outcome of the study was the rate of unplanned HR. It was defined as an admission to the hospital within 45 days of discharge from the same or another hospital due to health issues related to the PNL operation performed during the first admission without being scheduled in the primary treatment plan. The rationale for defining the upper limit of the time range of HR as 45 days after PNL was to cover the time range of JJ removal after PNL. At our institute, a significant proportion of our patients have JJ removal between 30 and 45 days after PNL.

This study was approved by the local ethical committee at our institute, and the institutional review board approval number is 3750011/2022. In addition, this study was registered in the Clinical Trials registry (ID: NCT05852483). All procedures involving human participants adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and its amend

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Qualitative (categorical) data (such as sex, age category, stone location, preoperative presence of pus cells or hydronephrosis, etc.) were presented in the form of frequency and percentage. However, quantitative (continuous) data (such as BMI, stone size, operative time, hospital stay, etc.) were presented as mean ± SD. Regarding the comparisons between the readmission and non-readmission groups, the χ2 test was used for the qualitative data, and the independent t-test was used for the quantitative data. The skewness of the data was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to define the predictors of unplanned HR. Multicollinearity of data was checked with the Belsley-Kuh-Welsch technique. A risk score was created for the independent predictors revealed from the multivariate analysis. The P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

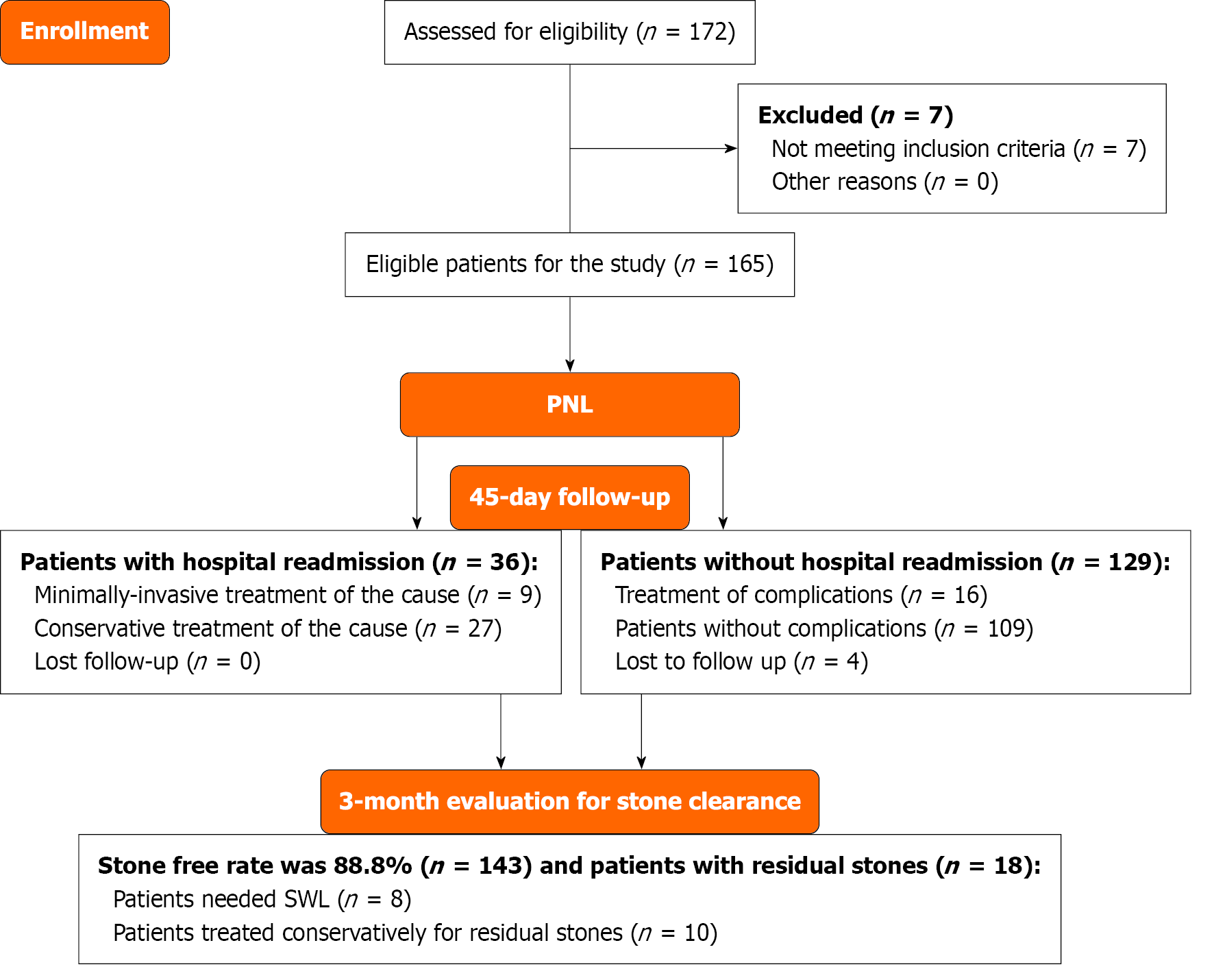

The current study included 161 patients, considering the proportion of patients lost to follow-up and the exclusion of ineligible patients (Figure 1). The age mean ± SD (range) was 44 ± 12.6 (20–65) years, female sex accounted for 39.8%, and the mean BMI ± SD was 24.4 ± 2.8 kg/m2. Thirty-six patients (22.4%) had unplanned HR after PNL. The differences between these characteristics in groups of patients with (readmitted group) or without (non-readmitted group) HR were not statistically significant (Table 1).

| Sociodemographic variables | Total (n = 161) | Readmitted (n = 36) | Non-readmitted (n = 125) | P value |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 97 (60.2) | 25 (69.4) | 72 (57.6) | 0.138 |

| Female | 64 (39.8) | 11 (30.6) | 53 (42.4) | |

| BMI | ||||

| Underweight (< 18) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 0.617 |

| Normal weight (18-25) | 101 (62.7) | 24 (66.6) | 77 (61.6) | |

| Overweight (25-30) | 47 (29.2) | 11 (30.6) | 36 (28.8) | |

| Obese (> 30) | 12 (7.5) | 1 (2.8) | 11 (8.8) | |

| BMI | 24.4 ± 2.8 | 24.1 ± 2.4 | 24.5 ± 2.9 | 0.430 |

| Age group | ||||

| From 20-39 years | 63 (39.1) | 17 (47.2) | 46 (36.8) | 0.091 |

| From 40-59 years | 78 (48.4) | 12 (33.3) | 66 (52.8) | |

| From 60-65 years | 20 (12.4) | 7 (19.4) | 13 (10.4) | |

| Mean age (years) | 44 ± 12.6 | 44.4 ± 12.7 | 43.9 ± 12.6 | 0.847 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 16 (9.9) | 1 (2.8) | 15 (12) | 0.133 |

| Married | 141 (87.6) | 35 (97.2) | 106 (84.8) | |

| Widow/widower | 4 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.2) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Office work | 37 (23) | 7 (19.4) | 30 (24) | 0.372 |

| Not working | 124 (77) | 29 (80.6) | 95 (76) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| High | 44 (27.3) | 9 (25) | 35 (28) | 0.565 |

| Secondary | 33 (20.5) | 9 (25) | 24 (19.2) | |

| Basic | 30 (18.6) | 5 (13.9) | 25 (20) | |

| Read and write | 16 (10) | 2 (5.5) | 14 (11.2) | |

| Illiterate | 38 (23.6) | 11 (30.6) | 27 (21.6) | |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 42 (26.1) | 12 (33.3) | 30 (24) | 0.261 |

| Rural | 119 (73.9) | 24 (66.7) | 95 (76) | |

| Special habits | ||||

| Smoking | 46 (28.6) | 12 (33.3) | 34 (27.2) | 0.521 |

| Use of excessive caffeine-containing beverages (café and tea) | 66 (41) | 16 (44.4) | 50 (40) | |

Postoperative infections (55.6%) were the commonest causes of HR, followed by urinary obstructions (13.9%) and hemorrhagic complications (11.1%). More than 80% of HRs occurred during the first 15 postoperative days. Most patients (88.9%) with HR had one HR, while 11.1% of them were readmitted twice. Most patients were treated conservatively, including antimicrobial therapy (83%). All the interventions were minimally invasive procedures: JJ or combined JJ and PCN were performed in 16.7% of patients. There was no mortality among all patients (Table 2).

| Variables | |

| Frequency of readmission | |

| Once | 32 (88.9) |

| Twice | 4 (11.1) |

| Causes of readmission | |

| Inflammatory causes | 20 (55.6) |

| Pyelonephritis | 15 (41.7) |

| Other forms of UTIs | 5 (13.9) |

| Hemorrhagic causes | 4 (11.1) |

| Hematuria | 2 (5.6) |

| Retroperitoneal hematoma | 2 (5.6) |

| Combined inflammatory and hemorrhagic causes | 4 (11.1) |

| Obstructive causes | 5 (13.9) |

| Anuria | 2 (5.6) |

| Acute urine retention | 3 (8.3) |

| Extra urinary causes | 3 (8.3) |

| Pulmonary complications | 2 (5.6) |

| Gastric ulcers | 1 (2.8) |

| Period from discharge to readmission | |

| 1-15 days after discharge | 29 (80.6) |

| 16-30 days after discharge | 5 (13.9) |

| 31-45 days after discharge | 2 (5.6) |

| Mean length of hospital stay of readmission (day) | 3.1 ± 2.8 |

| Readmission management | |

| Conservative treatment | 30 (83.3) |

| Insertion of JJ | 4 (11.1) |

| Insertion of both JJ and nephrostomy tube | 2 (5.6) |

The final SFR was 88.8% after 3 months postoperatively. Treatment of residual stones by extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy was performed in 8 patients (5%). However, no surgical interventions were carried out for residual stones; spontaneous passage occurred in 4 patients (2.5%), and dissolution therapy was used in 6 patients (3.7%).

In the comparison of preoperative clinical characteristics (Table 3), readmitted patients showed a significantly higher incidence of pus cells in the preoperative urine analysis (P = 0.001), larger mean stone size (P = 0.012), and more preoperative hydronephrosis (P = 0.001).

| Variables | Readmitted (n = 36) | Non-readmitted (n = 125) | P value |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 5 (13.9) | 19 (15.2) | 0.542 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (5.6) | 9 (7.2) | 0.537 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) | 0.641 |

| Nutrition and fluid assessment | |||

| Normal diet | 27 (75) | 100 (80) | 0.331 |

| Specific diet (diabetic, salt-free) | 9 (25) | 25 (20) | |

| Average fluid intake (2-3 L/day) | 28 (77.8) | 102 (81.6) | 0.383 |

| Fluid intake > 3 L/day | 8 (22.2) | 23 (18.4) | |

| Previous urological procedures | |||

| Endourologic surgery | 4 (11.1) | 23 (18.4) | 0.222 |

| Open surgery | 13 (36.1) | 36 (28.8) | 0.260 |

| ESWL | 2 (5.6) | 9 (7.2) | 0.537 |

| Laboratory investigations | |||

| Pus cells in urine analysis | 29 (80.6) | 58 (46.4) | 0.001 |

| Mean serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.24 ± 0.8 | 1.12 ± 0.6 | 0.321 |

| Mean hemoglobin level (g/dL) | 13.14 ± 2.3 | 12.9 ± 2.2 | 0.557 |

| Mean prothrombin time (second) | 12.4 ± 0.8 | 12.2 ± 0.7 | 0.095 |

| Preoperative findings in computed tomography | |||

| Mean stone size (cm) | 2.64 ± 0.71 | 2.31 ± 0.68 | 0.012 |

| Solitary kidney | 4 (11.1) | 5 (4) | 0.114 |

| Stone location | |||

| Right kidney | 22 (61.1) | 55 (44) | 0.052 |

| Left kidney | 14 (38.9) | 70 (56) | |

| Preoperative hydronephrosis | 26 (72.2) | 48 (38.4) | 0.001 |

| Presence of preoperative JJ | 8 (22.2) | 23 (18.4) | 0.383 |

Regarding the operative findings (Table 4), the readmitted patients exhibited significantly higher rates of multiple renal punctures (P < 0.001), longer mean total (P = 0.001) and procedural (P < 0.001) operative times, and a higher rate of JJ insertion (P = 0.033). The differences in indication (P = 0.082) and duration (P = 0.062) of JJ insertion did not reach statistical significance between the two groups (Table 4).

| Variables | Readmitted (n = 36) | Non-readmitted (n = 125) | P value1 |

| Operative variables | |||

| Approach | |||

| Infracostal | 31 (86.1) | 112 (89.6) | 0.555 |

| Supracostal | 5 (13.9) | 13 (10.4) | |

| Number of punctures | |||

| Single | 6 (16.7) | 63 (50.40 | < 0.001 |

| Multiples | 30 (83.3) | 62 (49.6) | |

| Target calyx of puncture | |||

| Upper calyx | 4 (11.1) | 12 (9.6) | 0.671 |

| Middle calyx | 9 (25) | 41 (32.8) | |

| Lower calyx | 23 (63.9) | 72 (57.6) | |

| Type of disintegrators | |||

| Ultrasonic | 2 (5.6) | 4 (3.2) | 0.403 |

| Pneumatic | 34 (94.4) | 121 (96.8) | |

| Academic qualification of the main operator | |||

| Professor | 16 (44.4) | 51 (40.8) | 0.665 |

| Assistant professor | 0 (0) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Lecturer | 19 (52.8) | 63 (50.4) | |

| Assistant lecturer | 1 (2.8) | 9 (7.2) | |

| Patient position | |||

| Supine | 2 (5.6) | 20 (16) | 0.167 |

| Prone | 34 (94.4) | 105 (84) | |

| Operative time | |||

| Total operation time (minute) | 182.5 ± 34.7 | 150.72 ± 31.3 | 0.001 |

| PNL procedural time (minute) | 158 ± 27.3 | 130 ± 29 | < 0.001 |

| Ureteral JJ | |||

| Number of patients | 12 (33.3) | 21 (16.8) | 0.033 |

| Duration | 43.3 ± 19 | 59.6 ± 25.5 | 0.062 |

| Indications | |||

| For residual stone | 10 (27.8) | 16 (12.8) | 0.082 |

| For other causes | 2 (5.6) | 5 (4) | |

| Nephrostomy tube | |||

| Number of patients | 33 (82.4) | 103 (82.4) | 0.136 |

| Removal before discharge | 33 (91.7) | 92 (73.6) | 0.146 |

| Removal after discharge (within 3 days) | 1 (2.8) | 10 (8) | |

| Postoperative Variables | |||

| UOP at the 1st postoperative 24 hours (mL) | 925 ± 210.95 | 956.80 ± 267.48 | 0.512 |

| Pain degree | |||

| No pain | 20 (55.6) | 75 (60) | 0.172 |

| Mild | 1 (2.8) | 15 (12) | |

| Moderate | 8 (22.2) | 23 (18.4) | |

| Sever | 7 (19.4) | 12 (9.6) | |

| Discharge with urethral catheter and its duration (day) | |||

| Discharge with urinary catheter | 24 (66.7) | 54 (43.2) | 0.011 |

| 2-7 | 18 (50) | 85 (68) | 0.014 |

| 8-13 | 10 (27.8) | 32 (25.6) | |

| 14-20 | 8 (22.2) | 8 (6.4) | |

| Mean duration with catheter | 9.5 ± 6 | 6.4 ± 3.7 | < 0.001 |

| Complications | |||

| Pneumothorax | 5 (13.9) | 7 (5.6) | 0.100 |

| Intraperitoneal fluid collection | 10 (27.8) | 6 (4.8) | < 0.001 |

| Postoperative urinary tract infection | 13 (36.1) | 20 (16) | 0.011 |

| Received pre-discharge instructions | |||

| Instructions about wound care | 16 (44.4) | 70 (56) | 0.150 |

| Instructions about medications | 25 (69.4) | 81 (64.8) | 0.379 |

| Activity daily living instructions | 12 (33.3) | 65 (52) | 0.048 |

| Instructions about urethral catheter care | 7 (19.4) | 55 (44) | 0.005 |

| Diet instructions | 8 (22.2) | 27 (21.6) | 0.550 |

| Follow-up appointment | 19 (68.2) | 63 (50.4) | 0.475 |

| Education on warning signs | 18 (50) | 57 (45.6) | 0.390 |

| Hospital stay (day) | 5.1 ± 3.8 | 4.6 ± 2.9 | 0.370 |

In the comparison of the postoperative characteristics (Table 4), the readmitted group had significantly higher rates of discharge with urethral catheter (P = 0.011), longer duration of urethral catheter (P < 0.001), intraperitoneal fluid co

For all patients, the minimum follow-up duration was 45 days. The modified Clavien-Dindo system was used to grade complications, based on the modality of treatment (Table 5).

| Complications | Frequency | Number of readmitted patients | Treatment regimen (number of patients) | Modified Clavein grade |

| Obstructive complications | ||||

| Anuria | 2 | 2 | JJ placement (2) | IIIa |

| Acute urinary retention | 3 | 3 | Urethral catheterization (3) | II |

| Renal pain/colic | 8 | 0 | Medical expulsive (8). Antimicrobial therapy (3) | II, II |

| Genitourinary infections | ||||

| Acute pyelonephritis | 18 | 15 | JJ placement (4) with percutaneous nephrostomy (2). Antimicrobial therapy (18) | IIIa, II |

| Other infection1 | 5 | 5 | Antimicrobial therapy | II |

| Hemorrhagic complications | ||||

| Gross hematuria | 5 | 2 | Blood transfusion, intravenous fluids, and anti-bleeding measures (2). Antibleeding measures only (3) | II, II |

| Retroperitoneal hematoma | 3 | 2 | Blood transfusion (1). Antimicrobial/antibleeding therapy (3) | II |

| Combined infections and hemorrhage | 4 | 4 | Blood transfusion (1). Antimicrobial therapy (4). Angioembolization (1) | II, II, IIIa |

| Extraurologic | ||||

| Pneumonia | 3 | 2 | Antimicrobial therapy (3) | II |

| Peptic ulcer | 1 | 1 | Upper GIT endoscopy and medical therapy | IIIa |

| Total | 52 | 36 | 42 II and 10 IIIa | |

In multivariate logistic regression, the presence of pus cells in preoperative urine analysis (P = 0.004), intraoperative injuries (P = 0.001), and inadequate nursing instructions for urethral catheter care (P = 0.035) were the independent predictors of unplanned HR after PNL. However, the operative time (P = 0.084), intraoperative insertion of JJ (P = 0.060), and discharge with a urethral catheter (P = 0.076) did not show statistical significance (Table 6).

| Potential predictors | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Preoperative predictors | |||

| Positive pus cells in urine analysis | 5.8 | (1.7-19.5) | 0.004 |

| Stone size | 0.6 | (0.23-1.5) | 0.282 |

| Preoperative hydronephrosis | 1.43 | (0.41-5) | 0.575 |

| Intraoperative predictors | |||

| Total operation time (minute) | 1 | (0.92-1.04) | 0.434 |

| PNL procedural time (minute) | 1.1 | (1-1.15) | 0.084 |

| Multiple renal punctures | 2.9 | (0.8-10.8) | 0.103 |

| Insertion of a double-J stent | 0.25 | (0.06-1.1) | 0.060 |

| Occurrence of intraoperative injuries | 15 | (3-75) | 0.001 |

| Postoperative predictors | |||

| Postoperative urinary tract infections | 0.58 | (0.43-9.91) | 0.554 |

| Discharge with urethral catheter | 1.1 | (1-1.3) | 0.076 |

| Duration of urethral catheterization | 1.13 | (1-1.3) | 0.110 |

| Inadequate activity daily living instructions | 0.12 | (0.14-1.26) | 0.123 |

| Inadequate urethral catheter care instructions | 0.25 | (0.08-0.9) | 0.035 |

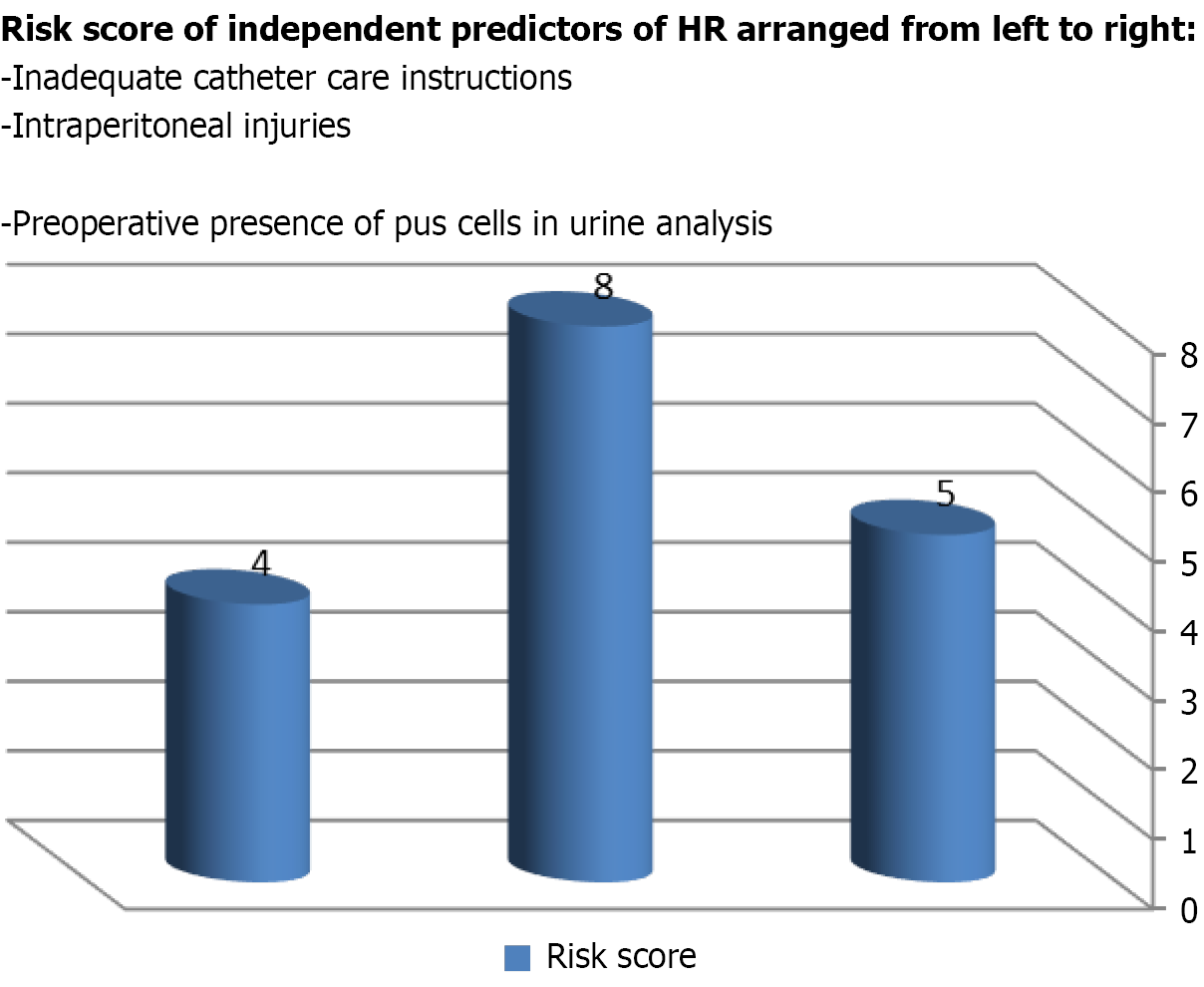

A clinical risk score was developed for the independent predictors identified by the multivariate regression model by converting the β-coefficients [ln(OR)] into integer scores (Figure 2). The total score ranges from 0 to 17, with higher scores indicating a greater risk of unplanned HR. Patients can be stratified into low (0–4), moderate (5–9), and high-risk (10–17) groups (Table 7).

| Item | Risk score |

| Predictors | |

| Positive pus cell in preoperative urine analysis | 5 |

| Intraperitoneal injuries | 8 |

| Inadequate catheter care instructions | 4 |

| Total score | 17 |

| Categorized score | |

| Low risk | 0–4 |

| Moderate risk | 5–9 |

| High risk | 10–17 |

PNL is the first-line treatment for large kidney stones, and it is regarded as a safe method[1]. The major complications associated with PNL are generally related to the intraoperative injuries of neighboring organs, postoperative bleeding, and UTIs. Unplanned HR may occur in the postoperative period due to unpredictable complications[3].

In the present study, the mean age of patients was 44 ± 12.6 years. Similarly, in a study by Tepeler et al[6], the mean age of the patients was 46.6 ± 13.2 years. Also, Keskin et al[7] reported a similar mean age of 42.1 ± 14.3 years[7].

In the current study, the mean BMI was 24 ± 2.8 kg/m2. This finding aligns with the findings of previous studies[6,15]. The current results showed that most patients had a normal BMI. This finding was consistent with earlier research, which referred to that the majority of patients with kidney stones also have a normal BMI[16].

The complication rate of PNL has improved from 75% in its early years to 30% in the current literature[17,18]. Simi

The rate of preoperative hydronephrosis in the readmitted patients was higher than that in the non-readmitted pa

The current results revealed that the presence of pus cells in the preoperative urine analysis was significantly higher in the readmitted patients than in the non-readmitted patients. This finding was similar to the results of the study by Danacıoğlu et al[3], who reported a significant difference between readmitted and non-readmitted patients in preo

The current study revealed a significant difference between readmitted and non-readmitted patients in the size of stones. This finding was similar to previous results. This can be explained by both the longer duration of the operation and the higher rates of residual stones or fragments[7]. In addition, if surgery is planned when patients are asymptomatic and the stone burden is not high, it may be possible to decrease the HR rate. Complex and large stones may require multiple access tracts and more maneuvers during operation to access various calyces, increasing the bleeding potential[8]. The large size of stones in previous studies resulted in prolonged operation time, a higher number of punctures, intraperitoneal injuries, and larger residual stones. The shortest median operative time was associated with the small sizes of stones. However, the medium-sized stones required a shorter operative time when compared to the large ones[23].

The current study showed that multiple punctures were significant predictors of HR. This finding was in agreement with previous results, where the upper pole access or multiple accesses were more likely associated with HR after PNL surgery[9]. Also, multiple renal accesses are usually required to manage complex and large stones within the complex pelvicalyceal systems. Multiple renal punctures and accesses increase the risk of parenchymal vascular injuries, thus increasing the risk of hemorrhage[8].

The present study revealed that JJ was a predictor of patient HR. This finding was in agreement with the results by Tomer et al[10], who showed that JJ placement was a significant risk factor for HR for PNL patients. Also, they reported that encrustation is a common phenomenon that can occur with the placement of JJ into the urinary tract, and it can lead to serious complications[10]. It has been reported that JJs act as foreign bodies and may cause UTIs, including pyonephro

The present results revealed that a large proportion of patients required NT post-PLN. This finding was consistent with Chang et al[24], who stated that the purpose of NT was kidney drainage to enhance hemostasis and healing of the access tract, prevent extravasation of urine, and provide access to the kidney for any auxiliary procedures. In addition, NT may be necessary for potential residual stones, which increase the risk of postoperative infections[24].

The current study demonstrated that postoperative UTIs were predictors of HR. This finding was in line with the results of a study by Khaleel and Farhan[12], who found that PNL was associated with postoperative fever and sepsis[12]. Also, Sharma et al[25] added that severe preoperative hydronephrosis, a higher number of punctures, and a longer dura

The current study revealed statistically significant differences between readmitted and non-readmitted patients, con

The current results showed that predischarge instructions for catheter care were risk factors for HR. Following basic infection control measures is a crucial duty for nurses to ensure proper urinary catheter care. Additionally, nurses should educate patients on the correct positioning of the catheter and drainage bag. These instructions help prevent ascending infections by promoting proper drainage and avoiding urine stagnation. It was reported that patients who receive proper education have an improved understanding of discharge instructions and a lower risk of HR[27,28].

Additionally, the present study showed a significant effect of pre-discharge instructions regarding ADLs on HR. Murray et al[29] defined ADLs as the essential skills required to independently care for oneself, including diet, bathing, and mobility. Furthermore, it was noted that ADLs have predictive value for HR and mortality in various conditions. Patients with impaired baseline physical functions are much more likely to experience HR within 30 days of hospital discharge[29].

Effective nursing interventions can greatly reduce HR after PNL. By emphasizing patient education, discharge planning, and post-discharge support, nurses can empower patients to manage their recovery, recognize potential com

The current study revealed a rate of HR after PNL of 22.4%. This finding was similar to the rate (27.1%) reported by Keskin et al[7], who attributed this high HR rate to major complications after PNL, such as infections, hemorrhage, and intraperitoneal injury[7]. However, Beiko et al[21] and Tepeler et al[6] reported lower HR rates after PNL (4%–15%)[6,21]. This difference in HR rates between our results and those of previous studies might further be attributed to the different definitions of HR and its duration.

The current results revealed that more than half (55.6%) of HRs were due to UTIs. This finding was in agreement with the results by Babich et al[30], who reported that 57.1% of readmitted patients had infections. The recurrent UTI was the most common cause[30]. Similarly, Kumar et al[20] reported that the most common cause of HR was urosepsis[20]. Keskin et al[7] mentioned that 9.6% of readmitted patients had post-PLN sepsis.

The current study reported that 11.1% of HRs were due to hemorrhagic causes. This finding was in line with the results of Keskin et al[7] and Beiko et al[21], who reported that 8.3% of HRs were due to hemorrhagic causes.

The current study revealed that about 8.3% of HRs were due to obstructive complications. This finding was in line with a study by Armitage et al[19]. Additionally, they reported that the acute urinary retention incidence was 0.5%. However, our study revealed that 5.6% of HRs were due to anuria, which was similar to previous results from our country[31].

The Clavien grading system has recently been used to evaluate the complications of PNL, and the grades are com

The combination of urological and nursing-related variables was a cardinal characteristic in the differences of the current study from most studies in the relevant literature[3,6,7,30]. While the similarities of the results were correlated to most variables, the natures of the predictors of HR after PNL have been remarkably varied per individual study[3,6,7,9-11,23]. This variation can be attributed to methodological differences among studies, such as the sample size, epidemiological study design, and definition of the variables[3,6,9,19,20]. Additionally, the technical differences in PNL proce

This study has the advantage of presenting the experience of studying the risk factors of HR after PNL in one of the developing countries with a high incidence of urolithiasis[5,31]. In addition, it addressed both the urological and healthcare risk factors for this significant topic in urolithiasis and endourology. Hence, this study design promotes the implementation of a recent protocol for perioperative patient care and management known as enhanced recovery after surgery. This protocol comprises domains for health education, nutrition assessment and intervention, postoperative fluid management, postoperative multimodal pain control, early postoperative mobilization, and early removal of indwelling urinary catheters or tubes. It requires multidisciplinary efforts of nurses, clinicians, anesthesiologists, and physical therapists[14].

The limitations of this study included the inability to address the rates of HR in subclasses of patients, such as the age groups, stone size categories, and types of intraoperative complications. In addition, the generalizability of the current results is limited by the single-center nature of the study.

Studies with large probability samples in different geographical regions are recommended to explore the main aspects of unplanned HR and maximize the benefits of combined studying of urological and nursing-related predictors of unplanned HR after PNL. In addition, practical training of both nurses and physicians should consider the significance of awareness of aspects of the other specialty on the patient outcomes after PNL.

Despite the high SFR, the unplanned HR rate after PNL was relatively high. The positive pus cells in preoperative urine analysis, large stone size, presence of preoperative hydronephrosis, number of renal punctures, intraoperative insertion of JJ, intraperitoneal injury, duration of urethral cauterization, postoperative UTIs, and inadequate instructions about urethral catheter care and ADLs were associated with an increased rate of HR. However, the independent predictors of HR after PNL were pus cells in preoperative urine analysis, intraperitoneal injuries, and inadequate instructions on urethral catheter care. The novel combined study of both the urological and nursing-related predictors in the current study revealed their significant effects on the unplanned HR after NL. The emphasis on this combination and its potential impact can enhance the practical performance of the medical teams and improve the clinical outcomes of kidney stone management by PNL, particularly in developing countries.

| 1. | Türk C, Petřík A, Sarica K, Seitz C, Skolarikos A, Straub M, Knoll T. EAU Guidelines on Interventional Treatment for Urolithiasis. Eur Urol. 2016;69:475-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 775] [Cited by in RCA: 1172] [Article Influence: 106.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang YB, Cui YX, Song JN, Yang Q, Wang G. Efficacies of Various Surgical Regimens in the Treatment of Renal Calculi Patients: a Network Meta-Analysis in 25 Enrolled Controlled Clinical Trials. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018;43:1183-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Danacıoğlu YO, Özlü DN, Akkaş F, Yenice MG, Taşçı Aİ. The Risk Factors of Unplanned Hospital Readmission Following Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy. J Acad Res Med. 2021;11:69-74. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Khanna A, Fedrigon D 3rd, Monga M, Gao T, Schold J, Abouassaly R. Postoperative Emergency Department Visits After Urinary Stone Surgery: Variation Based on Surgical Modality. J Endourol. 2020;34:93-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gadelkareem RA, Abdelsalam YM, Ibraheim MA, Reda A, Sayed MA, El-Azab AS. Is Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy the Modality of Choice Versus Extracorporeal Shockwave Lithotripsy for a 20 to 30 mm Single Renal Pelvic Stone with ≤1000 Hounsfield Unit in Adults? A Prospective Randomized Comparative Study. J Endourol. 2020;34:1141-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tepeler A, Karatag T, Tok A, Ozyuvali E, Buldu I, Kardas S, Kucukdagli OT, Unsal A. Factors affecting hospital readmission and rehospitalization following percutaneous nephrolithotomy. World J Urol. 2016;34:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Keskin SK, Danacioglu YO, Turan T, Atis RG, Canakci C, Caskurlu T, Erol A, Yildirim A. Reasons for early readmission after percutaneous nephrolithotomy and retrograde intrarenal surgery. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2019;14:271-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Loo UP, Yong CH, Teh GC. Predictive factors for percutaneous nephrolithotomy bleeding risks. Asian J Urol. 2024;11:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Roberts JL, Sur RL, Flores AR, Girgiss CBL, Kelly EM, Kong EK, Abedi G, Berger JH, Chen TT, Monga M, Bechis SK. Understanding Causes for Admission in Planned Ambulatory Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy. J Endourol. 2022;36:1418-1424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tomer N, Garden E, Small A, Palese M. Ureteral Stent Encrustation: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Management and Current Technology. J Urol. 2021;205:68-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ray RP, Mahapatra RS, Mondal PP, Pal DK. Long-term complications of JJ stent and its management: A 5 years review. Urol Ann. 2015;7:41-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khaleel AAA, Farhan SD. Unplanned Hospital Visit After Urinary Stone Procedure. DJM. 2022;22:94-105. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Abdelmowla RAA, Hussein AH, Shahat AA, Abdelmowla HAA, Abdalla MA. Impact of nursing interventions and patients education on quality of life regarding renal stones treated by percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Nursing Educ Pract. 2017;7:52. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Liu L, Xiao Y, Yue X, Wang Q. Safety and efficacy of enhanced recovery after surgery among patients undergoing percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2024;110:3768-3777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shin TS, Cho HJ, Hong SH, Lee JY, Kim SW, Hwang TK. Complications of Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Classified by the Modified Clavien Grading System: A Single Center's Experience over 16 Years. Korean J Urol. 2011;52:769-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Safdar OY, Alzahrani WA, Kurdi MA, Ghanim AA, Nagadi SA, Alghamdi SJ, Zaher ZF, Albokhari SM. The prevalence of renal stones among local residents in Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:974-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Singh AK, Shukla PK, Khan SW, Rathee VS, Dwivedi US, Trivedi S. Using the Modified Clavien Grading System to Classify Complications of Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy. Curr Urol. 2018;11:79-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mousavi-Bahar SH, Mehrabi S, Moslemi MK. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy complications in 671 consecutive patients: a single-center experience. Urol J. 2011;8:271-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Armitage JN, Withington J, van der Meulen J, Cromwell DA, Glass J, Finch WG, Irving SO, Burgess NA. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in England: practice and outcomes described in the Hospital Episode Statistics database. BJU Int. 2014;113:777-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kumar M, Pandey S, Aggarwal A, Sharma D, Garg G, Agarwal S, Sharma A, Sankhwar S. Unplanned 30-day readmission rates in patients undergoing endo-urological surgeries for upper urinary tract calculi. Investig Clin Urol. 2018;59:321-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Beiko D, Elkoushy MA, Kokorovic A, Roberts G, Robb S, Andonian S. Ambulatory percutaneous nephrolithotomy: what is the rate of readmission? J Endourol. 2015;29:410-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Karatag T, Buldu I, Kaynar M, Inan R, Istanbulluoglu MO. Does the presence of hydronephrosis have effects on micropercutaneous nephrolithotomy? Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47:441-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Doykov M, Kostov G, Doykova K. Factors Affecting Residual Stone Rate, Operative Duration, and Complications in Patients Undergoing Minimally Invasive Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chang S, Lin C, Kang C, Cheng M, Jou Y, Shen C, Chen P, Lai W. Presence of Residual Stones is Not a Contraindication for Tubeless Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy. Urol Sci. 2019;30:226-231. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sharma K, Sankhwar SN, Goel A, Singh V, Sharma P, Garg Y. Factors predicting infectious complications following percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol Ann. 2016;8:434-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shan A, Hasnain M, Liu P. Nursing Effect Analysis of Urinary Tract Infections in Urology Surgery Patients: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Indian J Surg. 2023;85:251-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gadelkareem RA, Khalaf RA, Khalil SS, Abozead SE. Is Prioritizing a Certain Method of Health Care Education of Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Suprapubic Catheterization Evidence-Based? A Systematic Review. Urol Nurs. 2022;42:79. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Park JY, Kim HL. A comprehensive review of clinical nurse specialist-led peripherally inserted central catheter placement in Korea: 4101 cases in a tertiary hospital. J Infus Nurs. 2015;38:122-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Murray KS, Prunty M, Henderson A, Haden T, Pokala N, Ge B, Wakefield M, Petroski GF, Mehr DR, Kruse RL. Functional Status in Patients Requiring Nursing Home Stay After Radical Cystectomy. Urology. 2018;121:39-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Babich T, Eliakim-Raz N, Turjeman A, Pujol M, Carratalà J, Shaw E, Gomila Grange A, Vuong C, Addy I, Wiegand I, Grier S, MacGowan A, Vank C, van den Heuvel L, Leibovici L. Risk factors for hospital readmission following complicated urinary tract infection. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | El-Nahas AR, Nabeeh MA, Laymon M, Sheir KZ, El-Kappany HA, Osman Y. Preoperative risk factors for complications of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urolithiasis. 2021;49:153-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/