INTRODUCTION

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a heterogenous group of inflammatory conditions that mainly affects small blood vessels and is often associated with autoantibodies targeted at proteinase 3 (PR3) or myeloperoxidase (MPO)[1]. AAV is associated with excess morbidity and premature death, with a previous study reporting all-cause mortality of approximately 38% at 7-year follow-up[2].

Mortality and morbidity outcomes in AAV continue to improve over time with advances in immunosuppressive treatment regimen. Nevertheless, both treatment and disease are associated with substantial morbidity, necessitating vigilance for complications including treatment-related cancer risks[3].

Despite improvements in morbidity and mortality, there are ongoing etiological uncertainties with AAV. Associations between cancer and AAV have been well-established, with past studies demonstrating increased risks of immunosuppression related non-melanoma skin cancer and cyclophosphamide-associated bladder cancer[4]. However, there are numerous studies that have also shown an association between AAV and other solid tumors including kidney cancer[5-7]. This suggests a potential alternative relationship including malignancy as a disease triggering factor for AAV or conversely, AAV arising as a paraneoplastic syndrome[8].

In this mini review, we aimed to specifically assess the epidemiological links between AAV and kidney cancer as this had not been specifically addressed on previous reviews. We also aimed to explore potential pathophysiological links between the two diseases and their management. Finally, we aimed to utilize that information to assess if changes to the assessment for kidney cancer were indicated via a specific screening tool.

A comprehensive search of the National Library of Medicine database via PubMed was performed in March 2024 to identify studies examining the relationship between AAV and kidney cancer. The search strategy included the terms: (kidney cancer OR renal cancer OR malignancy) AND (vasculitis OR AAV). To expand our review, the reference lists of relevant articles were manually examined, and additional targeted searches were conducted to address any gaps identified in the initial search. Only English-language publications were considered. Out of 118 search results, 37 articles were included based on a review of suitability based on their abstracts.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF CONCURRENT AAV AND KIDNEY CANCER

Previous studies have evaluated the incidence of malignancy in patients with AAV which observed varied, but elevated standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) of all-site solid tumors when compared to the general population – as high as 2.4 as per one study by Knight et al[9], which is noted to be twice the SIRs of the general population and to be equivalent to the SIRs for any cancer post-kidney transplantation after excluding non-melanoma skin cancer (i.e. 2.4)[10]. SIRs are the ratio of incident cases in a cohort to the incident cases that would be expected, for example, incidence rates in the general population vs those in patients with AAV as in this case. Another study demonstrated cumulative overall cancer incidence of 8% at 5-year follow-up and 13% at 8-year follow-up for patients diagnosed with AAV which is significantly higher than those without the condition[11]. Furthermore, the annual incidence rate of urological malignancies was noted to be 0.37% in a cohort of patients with all-cause chronic kidney disease[12].

Most of the studies demonstrate a more significant association between malignancy and PR3 AAV in comparison to malignancy and MPO AAV. This is possibly due to the typically relapsing remitting course of PR3 AAV requiring higher cumulative doses of immunosuppression or higher mortality associated with MPO AAV[11]. It has also been proposed that incidental findings of non-invasive tumors identified during initial diagnosis and follow-up for patients with AAV may also contribute to an increase in reported incidence of kidney cancer in this cohort.

There were no dedicated studies which looked specifically at the incidence of kidney cancer in patients with AAV. However, the SIR of kidney cancer was reported to be between 1.7 and 3.3 as per three retrospective data analyses evaluating the incidence of various cancer types in patients with AAV[6,13].

Two case studies reported AAV presentations alongside the presence of detectable kidney masses which were later confirmed to be renal cell carcinoma, one appearing in a 61-year-old male patient and the other in a 72-year old female patient[14]. Unfortunately, no further demographic data were included in these case reports and we have identified no studies which conveyed demographic details of patients presenting concurrently with AAV and kidney cancer or those who developed kidney cancer following AAV treatment.

ETIOLOGICAL AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL INTERLINKS BETWEEN AAV AND KIDNEY CANCER

AAV as a consequence of kidney cancer

The pathophysiology of AAV remains unclear, and multiple triggering factors have been proposed, including malignancy. Tatsis et al[15] performed a retrospective statistical analysis on 956 patients, 477 with PR3 vasculitis and 479 patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a control group. The investigators reported a statistically significant increased incidence of renal cell carcinoma in the PR3 vasculitis group (P = 0.0464) with an odds ratio of 8.7 compared to the control group. Of the 7 patients with PR3 vasculitis and renal cell carcinoma, 5 patients simultaneously presented with both conditions. However, PR3 antibodies were not found in malignant tissues obtained from the PR3 group[15]. The number of contemporaneous presentations calls into question the nature of this link-could AAV potentially arise as consequence of malignancy?

There have been multiple case reports of presentations of vasculitis including AAV as a paraneoplastic syndrome[16-19]. Solans-Laqué et al[20] identified 144 cases of patients with coexistent vasculitis and solid tumors, with renal cell carcinoma the second most commonly associated solid tumor behind non-small cell lung cancer (n = 20). Tsimafeyeu et al[17] noted an 8% incidence rate of paraneoplastic vasculitis in patients with metastatic kidney cancer, particularly leukocytoclastic vasculitis on the lower extremities which were confirmed on skin punch biopsy. Fibrin deposits and tumor antigen-antibody immune complexes were identified in the vascular wall on biopsy. Cross-reactivity between the antigens of the tumor and the cell surface proteins on the endothelial cell, and subsequent development of inflammation and necrosis could be a mechanism whereby malignancy leads to vasculitis in a paraneoplastic syndrome.

In a review of individuals with paraneoplastic vasculitis in those diagnosed with solid tumors, Solans-Laqué et al[20] reported an 1.2% incidence of concurrent presentation of AAV and malignancy in patients diagnosed with both conditions throughout their prospective follow-up period (1 in 86 patients with both malignancy and AAV). Concurrent presentation with cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis was significantly more frequent (9 out of 15 cases presenting with concurrent vasculitis and malignancy) compared to other forms of vasculitis. After therapy for the underlying malignancy, most patients in this cohort had a complete resolution of their vasculitis, which further supports a paraneoplastic relationship between AAV and malignancy[20].

Pankhurst et al[21] performed a retrospective review of 200 consecutive patients with AAV and identified 20 patients (14 with microscopic polyangiitis and 6 with granulomatosis with polyangiitis) who had a malignancy but with only 4 within this 200-patient cohort having a concurrent diagnosis of both malignancy and AAV. In the remaining cases, malignancy predated vasculitis by a median duration of 96 months, and there was no evidence suggestive of subsequent malignancy relapse following development of vasculitis which would have supported a paraneoplastic etiology of the vasculitis.

Predisposition of patients in an inflammatory state towards kidney cancer

This relationship can be evaluated conversely, to examine whether AAV could lead to the development of de novo malignancy. It has been well established that systemic chronic inflammatory conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis are associated with an increased overall cancer risk[22,23]. Localized chronic immune activation increases risk of malignancy in a variety of body systems. There is an increased colorectal cancer risk for patients with inflammatory bowel disease, with one study demonstrating a 7% colorectal cancer risk after 30 years which has necessitated screening colonoscopies in this patient group[24]. Hemminki et al[25] assessed the risk of lung cancer across 12 autoimmune diseases and found increased SIRs in all 12. However, those autoimmune conditions reported with a SIR greater than 2.0 were those known to present with lung manifestations. This suggests that although both systematic and local inflammatory autoimmune processes resulted in an increased risk of cancer, local inflammation displayed closer associations with de novo cancer risk. It is therefore plausible that chronic inflammation and necrosis at the kidney cancer cell surface secondary to the immune response to tumor antigens could predispose to vasculitis.

As noted previously, the SIR of kidney cancer in patients with AAV was reported to be between 1.7 and 3.3. However, these studies have not published a timeline of diagnosis of the two conditions in the patient groups they reviewed which limits our ability to pick apart this relationship. They have also not distinguished between PR3 and MPO AAV and their respective risks towards kidney cancer incidence. Going forward, it would be useful to evaluate this unknown to assess if an increased relapse rate in PR3 AAV may lead to an increase in kidney cancer risk[11]. This may become increasingly relevant as morbidity and mortality outcomes improve through advances in treatment and with time, the longer-term consequences for patients living with AAV are being observed.

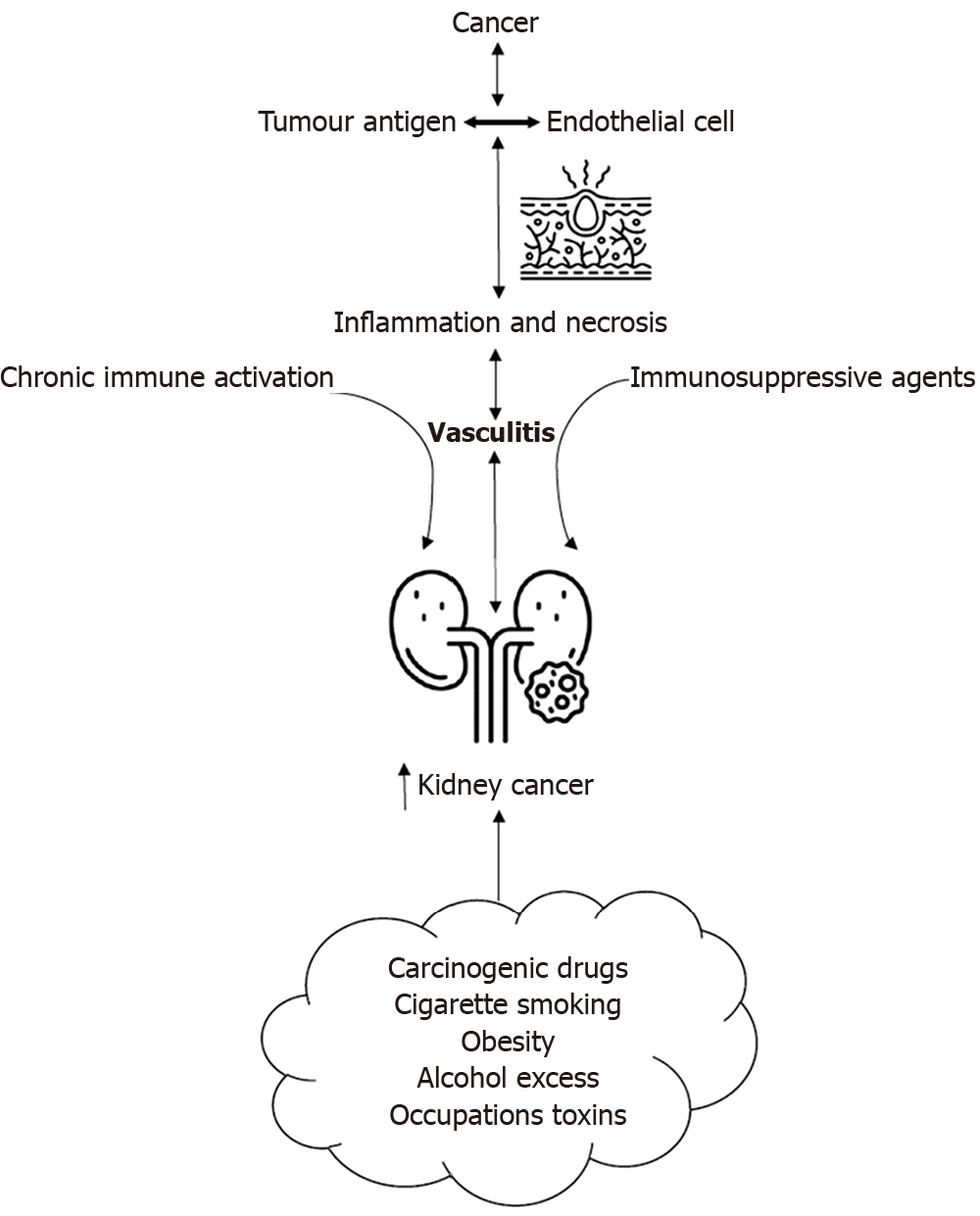

Figure 1 summarizes the plausible etiological and pathophysiological relationship that links AAV and kidney cancer as both a potential trigger and consequence, based on current evidence as discussed in the section above.

Figure 1 Plausible etiological and pathophysiological interlinks between anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and kidney cancer.

CONSIDERING THE ROLE OF CARCINOGENIC AND IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE TREATMENT IN AAV LEADING TO INCREASED CANCER RISK

Immunosuppressive agents have well-recognized carcinogenic properties, particularly cyclophosphamide, which has been linked to urinary tract cancer with risks increasing with higher cumulative doses such as those administered in patients treated for AAV[26]. This has been particularly highlighted in the study by Sánchez Álamo et al[27], in which much higher cumulative cyclophosphamide doses were used (in comparison to that from the post-CYCLOPS EULAR studies[28]), which was associated with significant increased risks of urological tract cancer. It has also been shown that concomitant use of Cyclophosphamide and Etanercept further increases this risk, with patients receiving both medications having an SIR for solid malignancy of 3.8 compared to 1.7 in those patients not receiving Etanercept[29]. However, Etanercept is not routinely used in the treatment of AAV. Azathioprine, Methotrexate and Rituximab have also been associated with an increased malignancy risk, though these agents have not been specifically linked with kidney cancer[30-32].

It is well-known immunosuppressive drug regimens carry an association with renal cell carcinoma in kidney transplant recipients[33,34]. Kidney transplant recipients have been shown to be at a 5-to-10-fold increased risk of developing renal cell carcinoma, particularly within the native kidneys, which make up 90% of all cases of renal cell carcinoma in transplant recipients[35,36]. The development of renal cell carcinoma in kidney transplant recipients has a multifactorial etiology, with a major cause being the malignant transformation of renal cysts which were already present when patients were receiving dialysis[35,36]. Despite this demonstrated elevated risk of malignancy, screening for renal cell carcinoma in kidney transplant recipients has not yet been proven to be cost-effective[37].

In addition to the carcinogenic risk of immunosuppressive drugs, immunosuppression in-itself is associated with an increased risk of kidney cancer. In a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive population, there is an 8.5-fold greater chance of developing renal cell carcinoma than the general population, with renal cell carcinoma typically presenting around 15 years earlier compared to the non-HIV affected general population[38]. This is likely due to reduced immune surveillance in immunocompromised individuals. Nevertheless, the risk of development of renal cell carcinoma directly secondary to HIV viral activity and host response cannot be excluded as well.

SCREENING FOR CONCURRENT AAV AND KIDNEY CANCER IN THE CLINICAL SETTING

From the evidence presented in this mini review, we advocate a perspective to encourage increased awareness of the potential associations that lie between kidney cancer and AAV. Considering the potential of malignancies including kidney cancer being a potential trigger for AAV should prompt screening for red-flag symptoms of malignancy, which includes observing a palpable kidney mass or abnormal renal imaging and visible hematuria during patient examination. The appearance of cutaneous vasculitic rash should also raise concerns of vasculitis presenting as a paraneoplastic syndrome.

During the ongoing maintenance phase of immunosuppression treatment, clinicians should be aware of patients having an increased risk of malignancies secondary to chronic immune activation, carcinogenic drugs and immunosuppressive effects impacting tumor surveillance. Risk of kidney malignancy is likely to increase further with the presence of established risk factors including cigarette smoking, obesity, hypertension, alcohol excess and occupational exposure such as trichloroethylene[39].

Akin to kidney transplant recipients, routine formal screening for kidney cancer in patients with AAV is unlikely to be a cost-effective strategy. However, due to the increased incidence of kidney cancer in this patient group, prompt investigation of potential kidney cancer-related symptoms, particularly in patients with known associated risk factors, should be considered as standard practice. In-office ultrasonography examination could be considered an effective, low-cost screening tool given the low incidence of AAV and potentially significant benefits for morbidity and mortality for patients of early detection of potential kidney malignancy.

The presence of new-onset microscopic hematuria should not only provoke the search for evidence of disease activity, but also to exclude potential renal tract malignancy.

LIMITATIONS AND REVIEW OF EVIDENCE

There are limitations placed on the scope of this review given the paucity of published evidence. There are no multi-center studies assessing the incidence of kidney cancer at presentation or at different timeframes from diagnosis hence the inability to make firm recommendations. In addition to this, the assessment of incidence was completed through retrospective data analysis which comes with inherent limitations such as missing data, selection bias and confounding variables. This method of research also comes with the inherent risk of skewed data due to publication bias which may highlight positive findings or unusual presentations such as the multiple case reports of co-presentation with AAV and kidney cancer, in which the actual incidence of this may be incredibly low. There was also notable heterogenicity in study designs when comparing incidence rates, contributing to the variability in reported SIRs. We would recommend further multi-center prospective studies assessing the incidence of the breadth of malignancies at and following diagnosis with AAV and the timeframes and therapies used in these cases, which would help further elucidate the relationship between AAV, cancer and immunosuppression.

CONCLUSION

As clinical outcomes improve for patients treated for AAV with advancements in available treatment options, the long-term sequelae of both the disease and its treatments are of increasing importance. The incidence of kidney cancer is higher in patients living with AAV compared to the general population, which may be the result of chronic immune activation or immunosuppression exposure. Therefore, awareness of red-flag symptoms and other risk factors related to kidney cancer are of increasing importance for clinicians involved in the long-term management of this patient population. As the incidence rate of kidney cancer in this patient group remains uncertain, a formal population-level screening approach for kidney cancer for patients with AAV would be unlikely to meet the criteria for a successful screening tool. For now, in clinical practice, a lower threshold for in-office ultrasound assessment or urgent urological assessment, particularly in patients with other risk factors for kidney cancer, should be considered when signs or symptoms of kidney cancer are present in patients with AAV.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: European Renal Association; American Society of Nephrology; International Society of Nephrology.

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade A, Grade B

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Gunes ME; Nhungo CJ S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li X