Published online Mar 25, 2024. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v13.i1.88028

Peer-review started: September 6, 2023

First decision: November 21, 2023

Revised: November 30, 2023

Accepted: January 11, 2024

Article in press: January 11, 2024

Published online: March 25, 2024

Processing time: 197 Days and 14.7 Hours

The Columbia classification identified five histological variants of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). The prognostic significance of these variants remains controversial.

To evaluate the relative frequency, clinicopathologic characteristics, and medium-term outcomes of FSGS variants at a single center in Pakistan.

This retrospective study was conducted at the Department of Nephrology, Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation, Karachi, Pakistan on all consecutive adults (≥ 16 years) with biopsy-proven primary FSGS from January 1995 to December 2017. Studied subjects were treated with steroids as a first-line therapy. The response rates, doubling of serum creatinine, and kidney failure (KF) with replacement therapy were compared between histological variants using ANOVA or Kruskal Wallis, and Chi-square tests as appropriate. Data were analyzed by SPSS version 22.0. P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

A total of 401 patients were diagnosed with primary FSGS during the study period. Among these, 352 (87.7%) had a designated histological variant. The not otherwise specified (NOS) variant was the commonest, being found in 185 (53.9%) patients, followed by the tip variant in 100 (29.1%) patients. Collapsing (COL), cellular (CEL), and perihilar (PHI) variants were seen in 58 (16.9%), 6 (1.5%), and 3 (0.7%) patients, respectively. CEL and PHI variants were excluded from further analysis due to small patient numbers. The mean follow-up period was 36.5 ± 29.2 months. Regarding response rates of variants, patients with TIP lesions achieved remission more frequently (59.5%) than patients with NOS (41.8%) and COL (24.52%) variants (P < 0.001). The hazard ratio of complete response among patients with the COL variant was 0.163 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.039-0.67] as compared to patients with NOS. The TIP variant showed a hazard ratio of 2.5 (95%CI: 1.61-3.89) for complete remission compared to the NOS variant. Overall, progressive KF was observed more frequently in patients with the COL variant, 43.4% (P < 0.001). Among these, 24.53% of patients required kidney replacement therapy (P < 0.001). The hazard ratio of doubling of serum creatinine among patients with the COL variant was 14.57 (95%CI: 1.87-113.49) as compared to patients with the TIP variant.

In conclusion, histological variants of FSGS are predictive of response to treatment with immunosuppressants and progressive KF in adults in our setup.

Core Tip: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is one of the most common glomerular diseases and a leading cause of kidney failure. FSGS is a heterogeneous disorder with many causes, varying pathogenesis and clinical courses. Columbia classification identified five histological variants of FSGS. The prognostic significance of these has remained controversial. Early studies found a good correlation of the variants with clinical presentation, treatment responses, and final outcomes. However, a more recent Japanese study found no prognostic value of the variants. The present study aimed to determine the clinical significance of these variants in a large sample of the Pakistani adult FSGS population.

- Citation: Jafry NH, Manan S, Rashid R, Mubarak M. Clinicopathological features and medium-term outcomes of histologic variants of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adults: A retrospective study. World J Nephrol 2024; 13(1): 88028

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v13/i1/88028.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v13.i1.88028

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a histological pattern of glomerular injury rather than a specific diagnosis. It can occur either in a primary or idiopathic form or may be associated with various systemic diseases, including auto

FSGS is one of the leading causes of glomerular diseases, particularly those presenting with nephrotic syndrome (NS), accounting for 20 to 40% of the pathological lesions in adult patients undergoing kidney biopsy for the evaluation of idiopathic NS[2-4]. It is also one of the most common glomerular diseases leading to kidney failure (KF) and KF requiring replacement therapy (KFRT)[2].

The classification of patients with FSGS is both challenging and controversial due to the wide variety of underlying etiologies, limited understanding of the pathogenesis, and the poor correlation between morphological lesions and response to treatment and clinical outcomes. The Columbia classification of FSGS provided a novel and pragmatic approach to classify FSGS based on histological features on kidney biopsy. This classification was supposed to help clinicians in the assessment of the prognosis of the disease and its response to therapy. The classification, first proposed by D'Agati et al[5], in 2004, envisioned five mutually exclusive histological variants of the disease, based entirely on light microscopic (LM) features[6]. These variants include collapsing (COL), not otherwise specified (NOS), tip (TIP), perihilar (PHI), and cellular (CEL) variants[2]. Since then, many studies of these variants have been conducted worldwide and have demonstrated a correlation of the variants with distinct clinical characteristics and prognostic and therapeutic outcomes[6-12]. The response rates are generally lowest for the COL variant, intermediate for the NOS variant, and highest for the TIP variant. On the other hand, the reported rates of KFRT are highest in the COL variant, intermediate in the NOS, and lowest in the TIP variant[13-16].

Other more recent studies have found no differences among these variants with respect to treatment responses and outcomes. A recent study from Japan by Kawaguchi et al[17] observed that FSGS variants alone have no significant impact on kidney outcomes after five years, while proteinuria remission was predictive of improved kidney prognosis irrespective of the variant. They suggested that specific strategies and interventions to achieve proteinuria remission for each variant should be implemented for better kidney survival.

We previously reported that whatever the histological variant of FSGS, timely treatment with immunosuppressive drugs of all patients who fulfill the criteria is very important to achieve remission, either complete or partial remission (PR). Those patients who achieved remission did not progress to KF and did not require replacement therapy in the medium-term follow-up period[2,18].

As steroids and cyclosporine (CsA)-induced remission is associated with better long-term survival, it is important to study which type of FSGS variants are more likely to respond to steroids and CsA treatment and whether such treatment affects kidney survival[2,14,17].

This study aimed to determine the relative frequency, clinicopathologic presentations, and outcomes of histological variants of FSGS in our population.

This retrospective observational study was conducted at the Department of Nephrology, Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation, Karachi, Pakistan. The study population comprised all adult patients (≥ 16 years) of either gender who were diagnosed with primary FSGS between January 1995 and December 2017. Secondary causes of FSGS were excluded. We did not analyze PHI and CEL variants in detail due to the small number of patients. Patients with missing infor

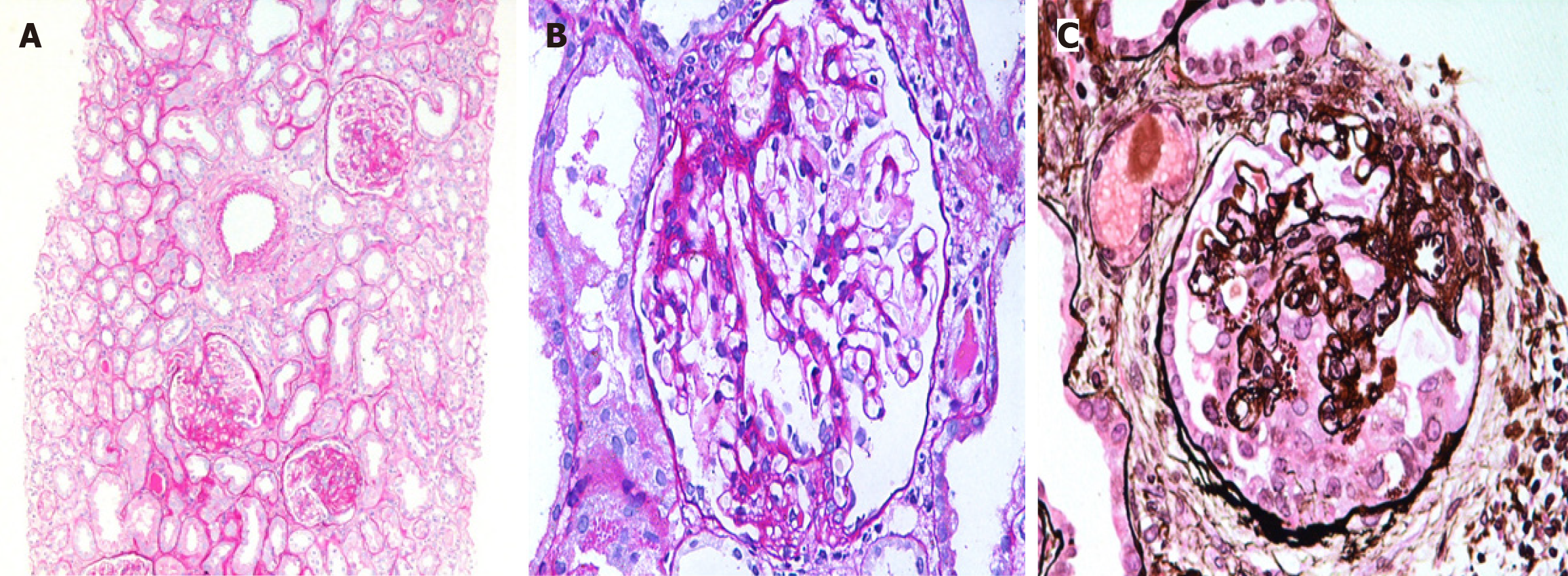

All patients underwent ultrasound-guided percutaneous native kidney biopsies, which were processed and prepared according to standard guidelines, as described in detail in our previous studies[2,18,19]. The histological variants were diagnosed as per the criteria of the Columbia classification[5,6]. Briefly, the TIP variant was diagnosed when at least one segmental lesion involved the tip domain (outer 25% of the tuft next to the origin of the proximal tubule). It required the exclusion of COL and PHI variants. The tubular pole needs to be identified in the defining lesion. FSGS, NOS, was diagnosed when at least one glomerulus showed a segmental increase in the mesangial matrix obliterating the capillary lumina, with or without segmental glomerular capillary wall collapse but without overlying podocyte hyperplasia. It required the exclusion of PHI, CEL, TIP, and COL variants. The COL variant was diagnosed when at least one glomerulus showed segmental or global collapse and overlying podocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia (Figure 1). The biopsies were reported by two experienced kidney pathologists and evaluated by LM, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. As the criteria for genetic testing in adult patients with FSGS are still unclear, genetic testing was not performed in this cohort of patients.

All patients with all variants of FSGS were treated in the same way. Briefly, unless contraindicated, all patients were treated with prednisolone, 1 mg/kg/d for the first six weeks followed by 0.75 mg/kg/d for the next six weeks. If no remission was achieved by the end of 12 wk, prednisolone was tapered over the next four weeks and stopped. If remission occurred at any time during treatment, the same dose of steroids was given for two more weeks before slow tapering. We did not employ different treatment protocols for different variants or different patients included in this study.

The steroid-resistant cases or those in which steroids were contraindicated were treated with CsA at a starting dose of 4 mg/kg/d. If a complete or PR occurred, CsA was continued for at least one year. If no response occurred by the end of two months, the use of CsA was discontinued.

Complete remission (CR) was defined as proteinuria ≤ 0.2 g/d or when the urine dipstick was negative for proteins with a stable serum creatinine concentration (< 50% increase from the baseline). PR was defined as proteinuria between 0.21-2.0 g/d with at least a 50% reduction in proteinuria from the baseline or albumin detected on dipstick (+1 to +4). Relapse was defined as proteinuria > 3 g/d after prior reduction of proteinuria to less than 2 g/d or albumin detected on dipstick (+1 to +3 or +4). Hypertension was diagnosed when patients were treated with antihypertensive drugs or with systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg. Elevated serum creatinine was defined as an increase of serum creatinine to > 1.4 mg/dL in male and > 1.2 mg/dL in female patients. KF was defined as a sustained increase of serum creatinine concentration > 50% from the baseline (at the time of kidney biopsy) or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 according to the modification of diet in renal disease equation. KFRT was defined as the need for continuous dialysis or kidney transplantation.

Data were collected by reviewing the medical record files of all selected patients. Data were collected over the period from diagnosis of primary FSGS to the last follow-up. The demographic characteristics (age, gender), BP measurements, and laboratory investigations including proteinuria, serum albumin, serum creatinine, and urine dipstick results for albumin/red blood cells on initial and last visits were noted. Drug information and side effects of steroids were obtained. The outcome of all patients regarding sustained remission, or progression to KF/KFRT, and death was noted.

Data were entered and analyzed by SPSS software 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the continuous and categorical variables. Continuous variables such as age, BP, serum creatinine, serum albumin, 24-h proteinuria, and drug dosages, are presented as mean ± SD and median ± interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Categorical variables, i.e., gender, sustained remission, KFRT, death, CR, PR, relapse, and hypertension are reported as frequencies and percentages. Mean differences for continuous variables and proportion differences for categorical variables between groups were compared using the student’s t-test and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Multivariate analysis for significant factors on univariate analysis was performed using the logistic regression method, while hazard ratios for risk factors of kidney outcome were calculated using the Cox regression model. Response rates, doubling of serum creatinine, and KFRT rates were compared between histological variants using ANOVA or Kruskal Wallis, and Chi-square tests as appropriate. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

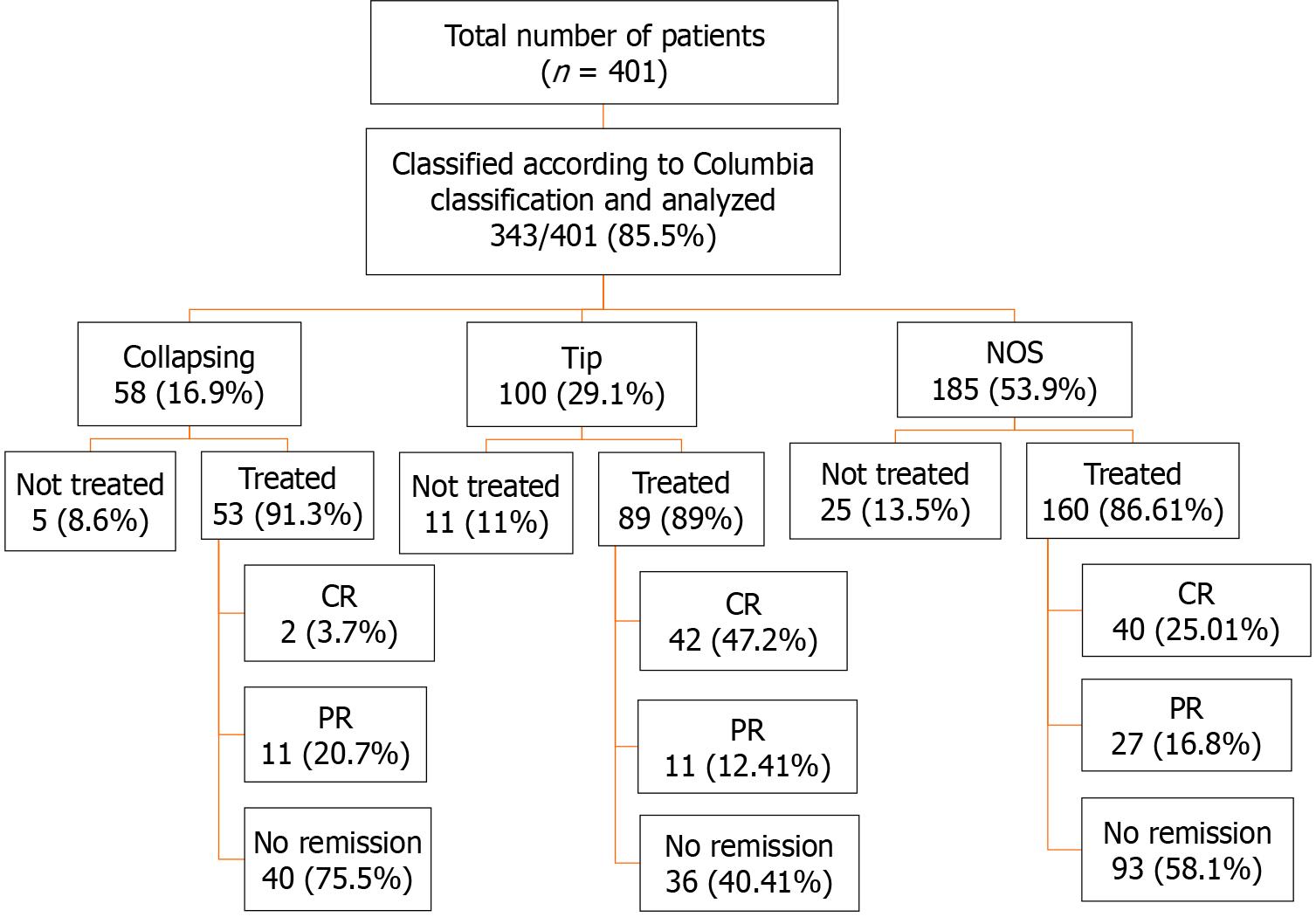

A total of 401 patients were diagnosed with primary FSGS during the study period. Among these, 352/401 (87.7%) had a designated Columbia histological variant. Among the latter, NOS was the commonest variant, found in 185 (53.9%) followed by the TIP variant in 100 (29.1%) patients. COL, CEL, and PHI variants were seen in 58 (16.9%), 6 (1.5%), and 3 (0.7%) patients, respectively. The three most common morphologic variants of FSGS (TIP, NOS, COL) comprised 343/352 (97.4%) and were included in the final analysis (Figure 2). The main demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics along with treatment information of these patients are shown in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean ages of the patients with the three variants (P = 0.7). A statistically significant difference was observed in the diastolic BP where patients with the COL variant showed a higher value of 87.6 ± 14.1 mmHg compared to other histologic variants (P = 0.04). Initial proteinuria was nephrotic-range in all patients with a median (IQR) of 3774 (2216-5900) mg/24 h and there was no significant difference among the variants (P = 0.418). The initial eGFR was 83.9 (55.9-127.4) mL/min/1.73 m2 in all patients with no significant difference among the three variants (P = 0.463). Elevated serum creatinine at presentation was found in 82 patients: Of these, 58 were males and 24 were females (P = 0.25). The mean follow-up duration in all patients was 36.5 ± 29.2 mo with no significant difference among the three variants (P = 0.114).

| Parameters | All patients (n = 343) | NOS (n = 185) | TIP (n = 100) | COL (n = 58) | P value |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 29.2 ± 12.0 | 29.3 ± 12.4 | 28.6 ± 11.2 | 30.1 ± 12.4 | 0.733 |

| Male to female ratio | 2.1:1 | 2.0:1 | 2.8:1 | 1.4:1 | 0.133 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg), mean ± SD | 128.8 ± 8.0 | 128.9 ± 18.9 | 127.5 ± 16.2 | 130.6 ± 18.9 | 0.575 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg), mean ± SD | 84.6 ± 12.6 | 84.8 ± 12.0 | 82.5 ± 12.5 | 87.6 ± 14.1 | 0.045 |

| Initial proteinuria (mg/24 h), IQR | 3774 (2216-5900) | 3602.5 (2125-5890) | 4250 (2535 -6530) | 3900 (2218-4800) | 0.418 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL), mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 0.863 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.830 |

| Initial eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), IQR | 83.9 (55.9-127.4) | 85.4 (57.8-128.3) | 82.3 (59.5-125.9) | 69.1 (41.9-127.3) | 0.463 |

| Elevated serum creatinine, n (%) | 82 (23.9) | 43 (52.4) | 20 (24.4) | 19 (23.2) | 0.607 |

| Males (> 1.4 mg/dL), n (%) | 58 (70.7) | 29 (67.4) | 17 (85.0) | 12 (63.2) | 0.257 |

| Females (> 1.2 mg/dL), n (%) | 24 (29.3) | 14 (32.6) | 3 (15.0) | 7 (36.8) | |

| Follow-up duration (month), mean ± SD | 36.5 ± 29.2 | 39.1 ± 31.5 | 31.4 ± 24.9 | 37.0 ± 27.7 | 0.114 |

| Total steroid dose (mg), mean ± SD | 4282.1 ± 1943.2 | 4266.9 ± 1884.1 | 4366.7 ± 2067.8 | 4186.1 ± 1935.3 | 0.858 |

| Duration of steroid treatment (wk), IQR | 18 (14-23) | 18 (14-23) | 19 (15-23.5) | 17 (13.5-20.5) | 0.359 |

| Total CsA dose (mg) mean ± SD | 27118.6 ± 24904.8 | 30002.4 ± 26537.5 | 25539.4 ± 28050.2 | 21549.7 ± 1657.7 | 0.447 |

| Duration of CsA treatment (wk), IQR | 16 (6.8-46.0) | 16 (8.0-54.0) | 17 (5.0-69.0) | 12 (4.0-28.0) | 0.727 |

Of 343 patients, 302 (88%) received treatment with immunosuppressive agents combined with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) as shown in Figure 2. All patients received steroids as initial therapy as per our treatment protocol. The total duration of steroid therapy and total dose of steroids are shown in Table 1. The total dose of CsA is also shown in Table 1. The remaining patients were treated with ACE inhibitors or ARBs only due to reasons such as uncontrolled diabetes, intolerance of steroids, risk of osteoporosis, and other complications of immunosuppressive drugs.

Table 2 shows the details of pathological findings in the three morphological variants of FSGS. Upon review of the histopathological findings, a statistically significant difference was found among the three most common variants with respect to the number of glomeruli with global sclerosis (P = 0.001), number of glomeruli with segmental collapse (P = 0.05), and mild and moderate tubular atrophy (P < 0.001).

| Histopathology | All patients (n = 343) | NOS (n = 185) | TIP (n = 100) | COL (n = 58) | P value |

| No. of glomeruli, mean ± SD | 17.3 ± 8.4 | 16.4 ± 8.7 | 18.1 ± 6.8 | 17.3 ± 9.7 | 0.370 |

| No. of glomeruli with global sclerosis, mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 2.2 | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 2.5 | 0.001 |

| No. of glomeruli with segmental collapse, mean ± SD | 2.9 ± 2.7 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 2.6 ± 2.8 | 13.7 ± 3.3 | 0.050 |

| Tubular atrophy, mild, n (%) | 175/201 (87.1) | 91 (52.0) | 49 (28.0) | 35 (20.0) | < 0.001 |

| Tubular atrophy, moderate, n (%) | 26/201 (12.9) | 9 (36.6) | 1 (3.8) | 16(61.5) | |

| Fibrointimal thickening of arteries, mild, n (%) | 25/32 (98.1) | 13 (52.0) | 7 (28.0) | 5 (20.0) | 0.413 |

| Fibrointimal thickening of arteries, moderate, n (%) | 7/32 (21.9) | 5 (27.8) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) |

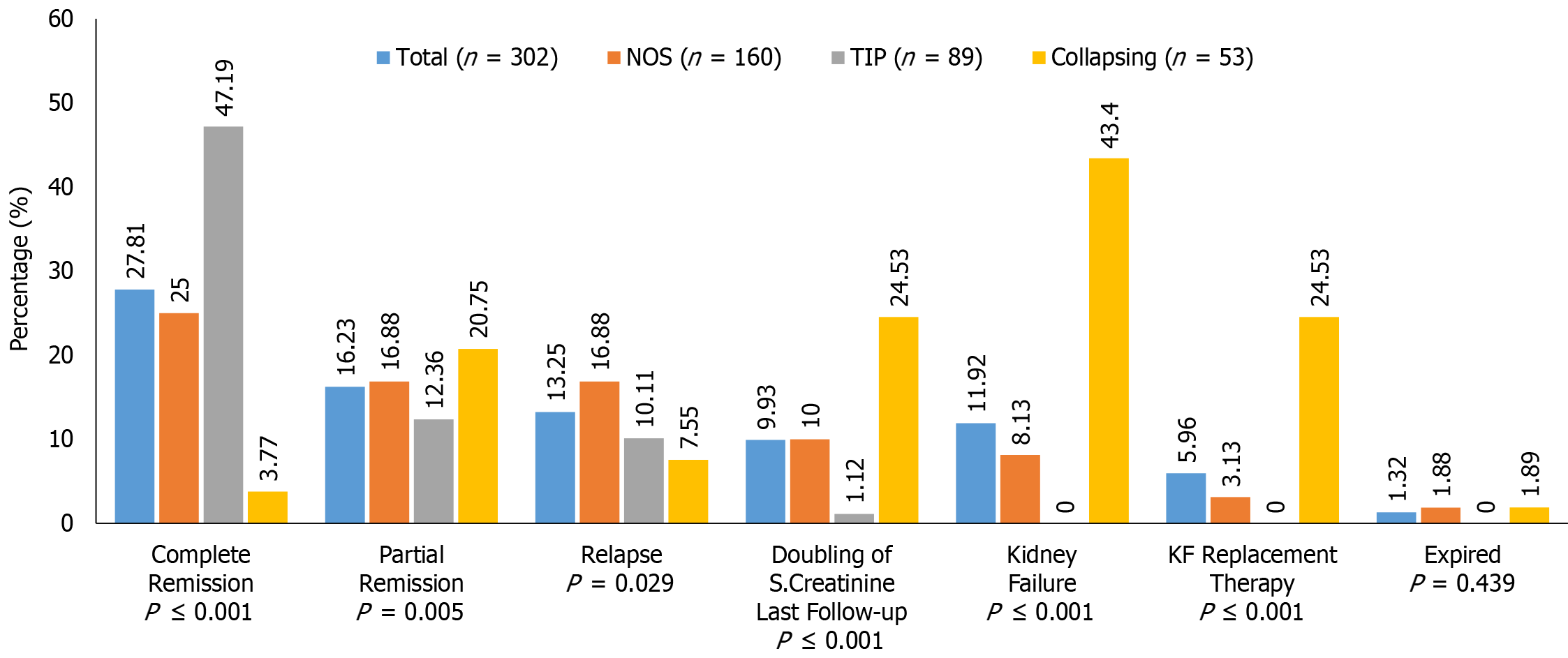

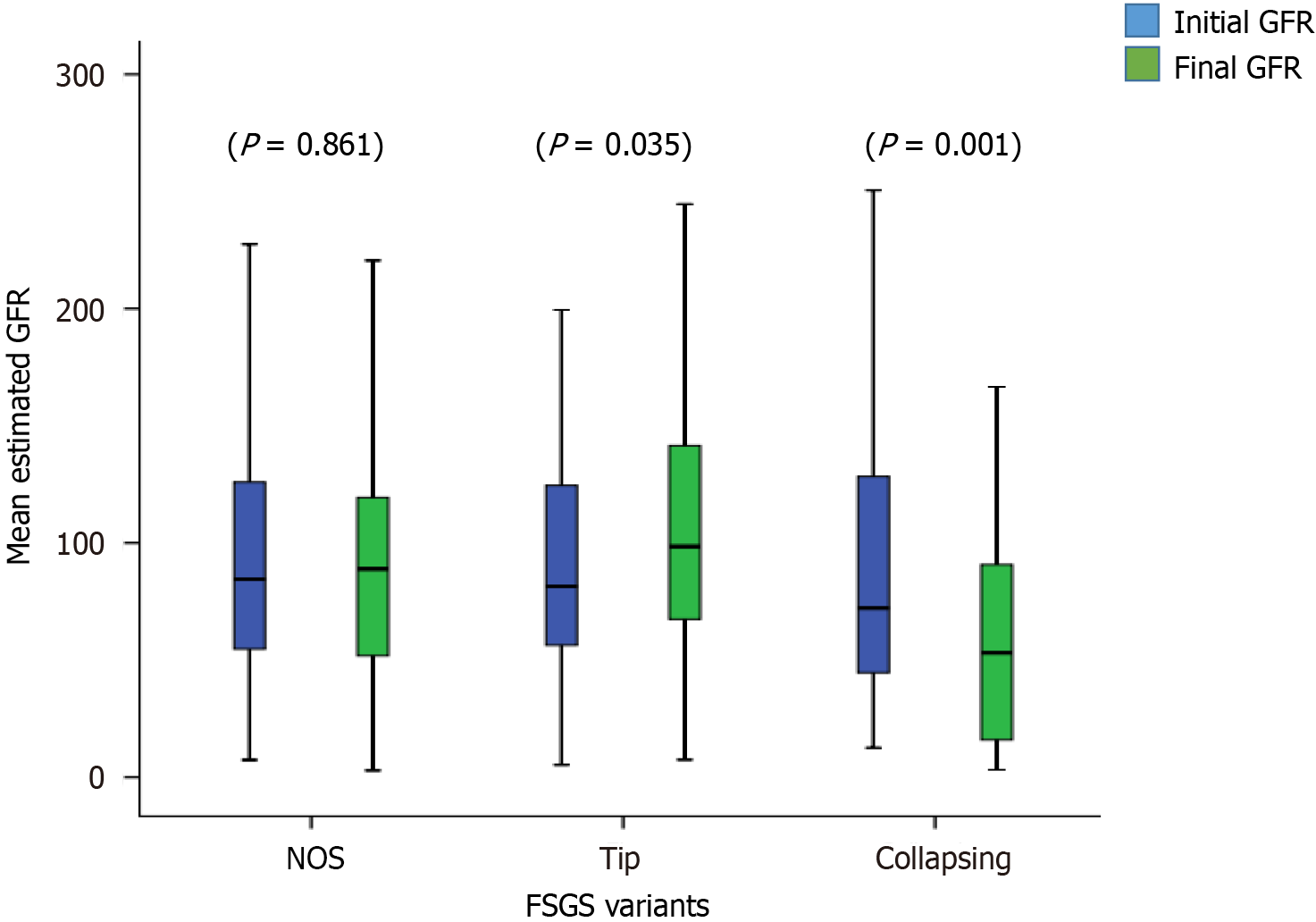

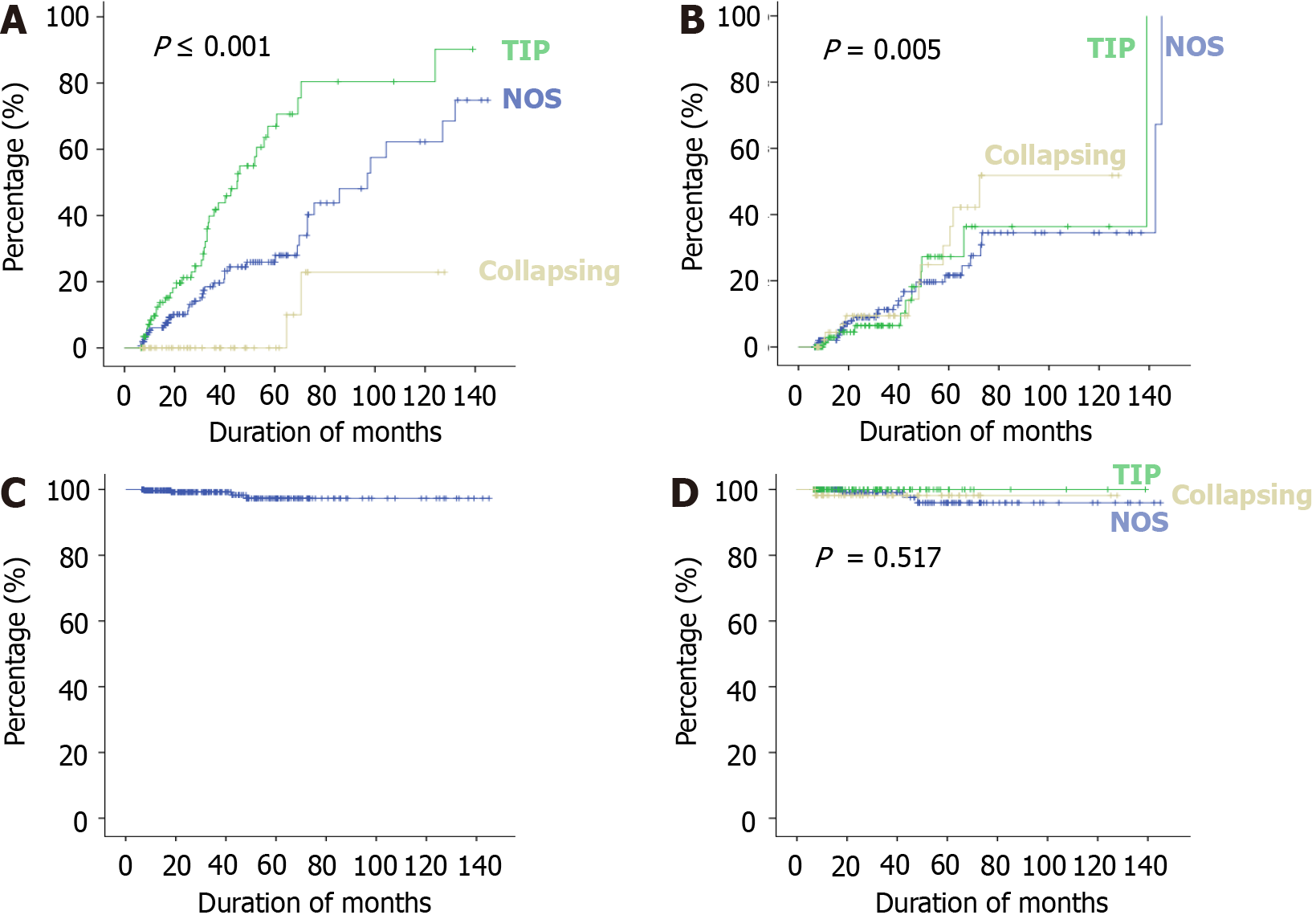

The treatment responses and clinical outcomes of all selected study subjects regarding complete and PR, or no remission, as well as progressive KF/KFRT, doubling of serum creatinine at last follow-up, final eGFR, relapse, and death of the patients are shown in Table 3. Of 302 patients, 84 (27.8%) achieved CR (Figure 2). Of these, 42 had the TIP variant, with a CR rate of 42/89 (47.2%), 40 had the NOS variant with a CR rate of 40/160 (25%), and 2 had the COL variant with a CR rate of 2/53 (3.7%) (P < 0.001). A total of 49/302 (16.2%) patients achieved PR. Among these, 11 had the TIP variant with a PR rate of 11/89 (12.4%), 27 had the NOS variant with a PR rate of 27/160 (16.8%), and 11 had the COL variant with a PR rate of 11/53 (20.8%) (P = 0.005). The highest percentage of no remission was found in patients with the COL variant at 40/53 (75.5%) followed by the NOS variant, 93/160 (58.1%) (P < 0.001) (Figure 3). The COL variant showed a marked decline in final eGFR and this was significant (P < 0.001) (Figure 4).

| Outcomes | All patients (n = 302) | NOS (n = 160) | TIP (n = 89) | COL (n = 53) | P value |

| Complete remission | 84 (27.8) | 40 (25.0) | 42 (47.1) | 2 (3.7) | < 0.001 |

| Partial remission | 49 (16.2) | 27 (16.8) | 11 (12.4) | 11 (20.8) | 0.005 |

| No remission | 169 (55.9) | 93 (58.1) | 36 (40.4) | 40 (75.5) | < 0.001 |

| Relapse | 40 (13.2) | 27 (16.9) | 9 (10.1) | 4 (7.5) | 0.029 |

| Final eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), mean ± SD | 92.1 ± 57.7 | 94.1 ± 59.1 | 110.3 ± 52.8 | 60.0 ± 46.9 | < 0.001 |

| Doubling of serum creatinine at last follow-up | 30 (9.9) | 16 (10.0) | 1 (1.1) | 13 (24..5) | < 0.001 |

| Kidney failure | 36 (11.19) | 13 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (43.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 18 (5.9) | 5 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 13(24.5) | < 0.001 |

| Expired | 4 (1.3) | 3 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 0.429 |

Among all treated patients, a doubling of serum creatinine was noted in 30 (9.9%) patients. Of these, 16/160 (10.0%) had the NOS variant, 1/89 (1.1%) had the TIP variant, and 13/53 (24.5%) had the COL variant (P < 0.001).

Regarding the development of KF, 23/53 (43.3%) patients with the COL variant developed progressive KF, 13/160 (18.1%) with the NOS variant, while none with the TIP variant progressed to KF during the mean follow-up period of 36.5 months (Figure 5). Similarly, 13/53 patients (24.5%) with the COL variant, 5/160 (3.1%) with the NOS variant, and none with the TIP variant required KFRT (P < 0.001). A total of four patients died, 1/53 (1.8%) with the COL variant, and 3/160 (1.8%) with the NOS variant with no significant difference among the three variants.

The final kidney and patient outcomes of the three common FSGS variants are shown in Figure 3. Patients with the TIP variant achieved remission more frequently (59.5%) than those with the NOS (41.8%), and COL (24.52%) variants (P < 0.001). The hazard ratio (HR) of complete response among patients with the COL variant was 0.163 (95%CI: 0.039-0.67) as compared to patients with the NOS variant. Patients with the TIP variant showed an HR of 2.50 (95%CI: 1.611-3.894) for CR compared to those with the NOS variant. Overall, progressive KF was observed more frequently in patients with the COL variant at 43.4% (P < 0.001). Among these, 24.53% of patients required kidney replacement therapy (KRT) (P < 0.001). The HR of doubling of serum creatinine among patients with the COL variant was 14.577 (95%CI: 1.872-113.493) as compared to patients with the TIP variant.

This is the largest study with a cohort of 343 adult patients with biopsy-proven primary FSGS classified according to the Columbia classification from Pakistan. This study analyzed in detail the three most common morphological variants of primary FSGS, namely the NOS, TIP, and COL variants, as the numbers with the remaining two variants were very small. The vast majority of patients included in this study received treatment with steroids and CsA along with ACE inhibitors and ARBs. The total number of patients with the NOS variant was 185; of which, 160 (86.4%) patients received treatment. Likewise, there were 100 patients with the TIP variant; of which, 89 (89%) received treatment. There were 58 patients with the COL variant; of which, 53 (91.3%) patients received treatment. There is marked variation among these variants with regard to their frequency, clinical presentation, response to treatment, and prognosis in different regions of the world.

The exact reason for the paucity of PHI and CEL variants is not clear but there may be a misclassification of the CEL variant as the TIP variant, as CEL lesions can exist within the tuft at the tubular pole as the tip location and intracapillary expansive foam cells can be observed in both variants[7].

This is one of the largest cohorts of patients with COL FSGS in the Asian population as other studies from Asia did not include such a large number of patients with this lesion. A study on a Korean population of 111 patients with primary FSGS showed 63% NOS, 18% TIP, 15% PHI, 3% CEL, and only one patient with COL FSGS[8].

In general, there is a wide diversity in the prevalence of different variants of FSGS in different regions. In a Brazilian report, NOS was the most common variant, followed by COL[7]. It was also observed that there was a substantial overlap of criteria for the NOS and PHI variants as well as for COL and CEL variants. With regard to the CEL variant, it has been claimed that it is merely a form of the COL variant, and histologically it is very difficult to differentiate between these two variants. In fact, a common pathophysiological pathway affecting cell cycle regulatory proteins has been suggested for both variants[7]. A literature review also showed that the COL variant is less common in Whites than in the Black race as compared to NOS, TIP, PHI, and CEL variants, which are not common in the Black race[6,8,12].

A literature review of published studies on the Asian population showed that in China and India, TIP, NOS, and CEL variants are more frequent morphological variants with different treatment outcomes[16,20-22]. On the contrary, we found different results in our population. Shakeel et al[19] studied a large cohort of 184 patients from our center. They found that the COL variant was the second most common morphological variant of FSGS in our patients. These results were different to the Indian cohort as described previously. A more recent study from our institute evaluated the long-term outcome of adults with primary FSGS and showed a large number of patients with the COL variants after the NOS and TIP variants[2]. However, PHI and CEL variants were not common in our population as we did not find a significant number of patients with both these variants. A recent study from Japan showed a significant number of patients with PHI and CEL variants with no significant difference in outcome after treatment among different morphological variants of FSGS[17].

In our study, the majority of patients were young with an average age of 29 years, and all presented with nephrotic-range proteinuria. The mean follow-up period in our study was approximately 3 years. The primary outcome was the response to treatment and the secondary outcome was the composite outcome of the doubling of serum creatinine and KF with or without KRT. In addition, we also evaluated the improvement in eGFR as an additional outcome feature. We observed a good overall response to treatment in terms of achieving CR and PR. As in previous studies, this was highest in patients with the TIP variant, intermediate in those with the NOS variant, and lowest in patients with the COL variant. With the TIP variant, there was a > 34% increase in eGFR from the baseline after treatment which was a marked response to treatment, while in the NOS variant, eGFR increased to > 10% and in the COL variant, there was a decrease in eGFR of 13% at the end of the follow-up period. Only one patient with the TIP variant developed a doubling of serum creatinine and no patients required KFRT or expired in this group. There was a significant decline in eGFR in patients with the COL variant with only two patients out of 53 achieving CR, and 40 patients out of 53 achieved no remission. This poor outcome in those with the COL variant is similar to previous studies and observations worldwide[11,23-27]. This variant has always remained aggressive with a poor response to therapy[28-31]. However, a recent study from Japan showed almost similar outcomes for this variant compared to other variants except for the TIP variant. They proposed that this may be due to improved immunosuppressive treatment in recent years[17].

The poor outcomes in patients with the COL variant in our study are alarming in the sense that we have a large number of patients with the COL variant which ultimately can result in an increased burden of KFRT in patients in the much younger population. In those with the NOS variant, we observed that 93/160 (58.1%) patients achieved no remission. Overall, the TIP variant showed a very good response to therapy in terms of primary and secondary composite outcomes.

Two of our recent studies showed that almost half of the adults with primary FSGS achieved sustained remission with steroids and immunosuppressants, and consequently exhibited excellent short- to long-term kidney outcomes[2,18]. Almost the same results were obtained in this study in that of 302 patients, slightly less than half of the patients achieved sustained remission while 169 patients achieved no remission with a wide diversity of responses to treatment in different variants.

There are certain strengths as well as limitations in this study. The strengths include a large sample size, homogeneous race and uniform treatment protocol in all patients. Meticulous and accurate classification of morphological variants by experienced nephropathologists is also a strength of the study. We also noted some unique findings in this study. The prevalence of COL variant was quite high as compared with other regional studies. We also showed that morphological variants, if accurately classified, do have therapeutic and prognostic importance. The limitations include the single-center and retrospective nature of the study. The follow-up duration was not very long. Two variants were not analyzed due to very small numbers. Moreover, genetic testing was not performed in this cohort of patients, as currently the indications for genetic testing in adult patients with FSGS are unclear. A pilot project to study the role of genetics in adult nephrotic patients at our center is in the pipeline and its results will be published in due course.

The histological variants of primary FSGS according to Columbia classification are associated with different clinicopathological presentations and are predictive of response to treatment and progressive KF. There was a large number of patients with the COL variant in this study, which is different to the rest of the Asian populations. These are results from a single center, and other studies are needed in order to compare the results and establish guidelines to effectively treat primary FSGS patients with different morphological variants.

The classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is controversial and challenging. There is still a lack of a unified and consensus-based approach to classify this disease, which will be both practical and clinically useful.

This study addressed the clinical utility of the morphological classification of FSGS in real-world scenarios. We aimed to investigate the therapeutic and prognostic significance of the morphological variants of FSGS in a large cohort of adult patients.

This study aimed to determine the relative prevalence, clinicopathologic presentations, and outcomes of the morphological variants of FSGS in a large cohort of adult patients at a single center in Pakistan.

This retrospective study included all consecutive adults (≥ 16 years) with biopsy-proven primary FSGS from January 1995 to December 2017. Studied subjects were treated uniformly with steroids and cyclosporine. The response rates and kidney outcomes were compared between histological variants using appropriate statistical tests. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The not otherwise specified (NOS) variant was the most common, being found in 185 (53.9%) patients, followed by the TIP variant in 100 (29.1%) patients. Collapsing (COL), cellular, and perihilar variants were seen in 58 (16.9%), 6 (1.5%), and 3 (0.7%) patients, respectively. The response rates were highest in patients with the TIP variant and lowest in those with the COL variant. Kidney outcomes were best in patients with the TIP variant and worst in those with the COL variant. The NOS variant was intermediate.

The morphological variants of FSGS are relevant and should be utilized to inform treatment and prognosis in individual patients. Combining these with other clinicopathological features to refine their predictive value needs to be investigated in future studies.

A holistic approach to disease categorization needs to be developed, which is practical and clinical-friendly.

| 1. | Woo KT, Chan CM, Foo M, Lim C, Choo J, Chin YM, Teng EWL, Mok I, Kwek JL, Tan HZ, Loh AHL, Wong J, Kee T, Choong HL, Tan HK, Wong KS, Tan PH, Tan CS. Impact of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis over the past decade. Clin Nephrol. 2023;99:128-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jafry N, Mubarak M, Rauf A, Rasheed F, Ahmed E. Clinical Course and Long-term Outcome of Adults with Primary Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2022;16:195-202. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kazi JI, Mubarak M, Ahmed E, Akhter F, Naqvi SA, Rizvi SA. Spectrum of glomerulonephritides in adults with nephrotic syndrome in Pakistan. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:38-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nada R, Kharbanda JK, Bhatti A, Minz RW, Sakhuja V, Joshi K. Primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adults: is the Indian cohort different? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3701-3707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | D'Agati VD, Fogo AB, Bruijn JA, Jennette JC. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:368-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | D'Agati V. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:117-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Testagrossa LA, Malhelros DMAC. Study of the morphologic variants of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a Brazilian report. J Bras Patol Med Lab. 2012;48:211-215. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kwon YE, Han SH, Kie JH, An SY, Kim YL, Park KS, Nam KH, Leem AY, Oh HJ, Park JT, Chang TI, Kang EW, Kang SW, Choi KH, Lim BJ, Jeong HJ, Yoo TH. Clinical features and outcomes of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis pathologic variants in Korean adult patients. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stokes MB, D'Agati VD. Morphologic variants of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and their significance. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21:400-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | D'Agati VD, Alster JM, Jennette JC, Thomas DB, Pullman J, Savino DA, Cohen AH, Gipson DS, Gassman JJ, Radeva MK, Moxey-Mims MM, Friedman AL, Kaskel FJ, Trachtman H, Alpers CE, Fogo AB, Greene TH, Nast CC. Association of histologic variants in FSGS clinical trial with presenting features and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:399-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Deegens JK, Steenbergen EJ, Borm GF, Wetzels JF. Pathological variants of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in an adult Dutch population--epidemiology and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:186-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chun MJ, Korbet SM, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in nephrotic adults: presentation, prognosis, and response to therapy of the histologic variants. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2169-2177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Arias LF, Jiménez CA, Arroyave MJ. Histologic variants of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: presentation and outcome. J Bras Nefrol. 2013;35:112-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Korbet SM. Treatment of primary FSGS in adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1769-1776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thomas DB, Franceschini N, Hogan SL, Ten Holder S, Jennette CE, Falk RJ, Jennette JC. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis pathologic variants. Kidney Int. 2006;69:920-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tang X, Xu F, Chen DM, Zeng CH, Liu ZH. The clinical course and long-term outcome of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in Chinese adults. Clin Nephrol. 2013;80:130-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kawaguchi T, Imasawa T, Kadomura M, Kitamura H, Maruyama S, Ozeki T, Katafuchi R, Oka K, Isaka Y, Yokoyama H, Sugiyama H, Sato H. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis histologic variants and renal outcomes based on nephrotic syndrome, immunosuppression and proteinuria remission. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37:1679-1690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jafry N, Ahmed E, Mubarak M, Kazi J, Akhter F. Raised serum creatinine at presentation does not adversely affect steroid response in primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adults. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1101-1106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shakeel S, Mubarak M, I Kazi J, Jafry N, Ahmed E. Frequency and clinicopathological characteristics of variants of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adults presenting with nephrotic syndrome. J Nephropathol. 2013;2:28-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Das P, Sharma A, Gupta R, Agarwal SK, Bagga A, Dinda AK. Histomorphological classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a critical evaluation of clinical, histologic and morphometric features. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012;23:1008-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nuguri S, Swain M, Padua M, Gowrishankar S. A Study of Focal and Segmental Glomerulosclerosis according to the Columbia Classification and Its Correlation with the Clinical Outcome. J Lab Physicians. 2023;15:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Swarnalatha G, Ram R, Ismal KM, Vali S, Sahay M, Dakshinamurty KV. Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis: does prognosis vary with the variants? Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2015;26:173-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schwartz MM, Korbet SM, Rydell J, Borok R, Genchi R. Primary focal segmental glomerular sclerosis in adults: prognostic value of histologic variants. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:845-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Carney EF. Glomerular disease: association of FSGS histologic variants with patient outcomes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Choi MJ. Histologic classification of FSGS: does form delineate function? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:344-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tsuchimoto A, Matsukuma Y, Ueki K, Tanaka S, Masutani K, Nakagawa K, Mitsuiki K, Uesugi N, Katafuchi R, Tsuruya K, Nakano T, Kitazono T. Utility of Columbia classification in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: renal prognosis and treatment response among the pathological variants. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1219-1227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Trivedi M, Pasari A, Chowdhury AR, Abraham-Kurien A, Pandey R. The Spectrum of Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis from Eastern India: Is It Different? Indian J Nephrol. 2018;28:215-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Han MH, Kim YJ. Practical Application of Columbia Classification for Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:9375753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ozeki T, Nagata M, Katsuno T, Inagaki K, Goto K, Kato S, Yasuda Y, Tsuboi N, Maruyama S. Nephrotic syndrome with focal segmental glomerular lesions unclassified by Columbia classification; Pathology and clinical implication. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0244677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Meehan SM, Chang A, Gibson IW, Kim L, Kambham N, Laszik Z. A study of interobserver reproducibility of morphologic lesions of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Virchows Arch. 2013;462:229-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Vlasić-Matas J, Glavina Durdov M, Capkun V, Galesić K. Prognostic value of clinical, laboratory, and morphological factors in patients with primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis - distribution of pathological variants in the Croatian population. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:PH121-PH128. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: Pakistan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tanaka H, Japan S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Zhao S