DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION OF AKI

According to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes clinical practice guideline, AKI is defined as an increase in serum creatinine by ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 h or increase to ≥ 1.5 times the baseline value within the past 7 d or urine volume < 0.5 mL/kg/h for a duration of 6 h[4]. AKI can be classified into three main categories based on etiology: Hemodynamic causes, urinary tract obstruction, and intrinsic renal diseases. Hemodynamic causes are associated with impaired renal perfusion, while urinary tract obstruction refers to blockages that prevent normal urine flow. Intrinsic renal diseases involve conditions affecting the kidney's internal structures, such as glomerulonephritis or tubulointerstitial diseases. It is important to highlight that what was previously termed prerenal AKI is now referred to as hemodynamic AKI. While prerenal logically suggests any insult occurring before the kidney, it is often misunderstood in clinical practice and used synonymously with volume depletion-related AKI. This narrow interpretation disregards other important factors, such as congestive nephropathy resulting from volume excess or conditions associated with compromised blood supply or renal vasoconstriction. Therefore, the term hemodynamic AKI is more comprehensive and encompasses all conditions that can adversely affect renal perfusion. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that while above classification provides a basic framework, AKI etiology in clinical practice is often more complex, with multiple pathologies coexisting. In certain contexts, it may be more appropriate to use a syndrome-based nomenclature, such as cardiorenal, hepatorenal, hepatocardiorenal, or sepsis-associated AKI, to better describe the underlying conditions[1,5]. To maintain simplicity, we will describe the role of POCUS using broad categories of AKI in this review.

POCUS IN HEMODYNAMIC AKI

Accurate assessment of fluid status, or more specifically, hemodynamic assessment, is crucial in the management of hemodynamic AKI. Unfortunately, conventional physical examination lacks sensitivity in this regard, and the introduction of POCUS has significantly improved bedside evaluation[6,7]. POCUS, when performed and interpreted by a skilled practitioner, provides comprehensive information about the entire hemodynamic circuit, and enables informed decision-making regarding the requirement for volume resuscitation or decongestive therapy. The outdated approach of administering intravenous fluids in a trial-and-error manner when volume status is uncertain is no longer justifiable in the era of POCUS. This holds significant importance, especially considering the growing recognition of the detrimental effects of fluid overload on renal and overall outcomes in conditions such as heart failure and critical illness. For instance, in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 31076 critically ill patients, for every liter increase in positive fluid balance, the risk of mortality increased by a factor of 1.19 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.11-1.28][8]. Although association does not imply causation, it is crucial to approach intravenous fluids as medications and administer them only when there is a clear indication. Notably, a recent clinical trial demonstrated the safety of a restrictive fluid management strategy in patients with septic shock, as compared to standard care (i.e., liberal strategy). Although the outcome did not show superiority in the restrictive group, it is worth mentioning that the liberal group received significantly less fluid compared to previous studies that demonstrated harm, with a median of 3.8 liters[9]. In the context of heart failure, the significance of venous congestion causing renal dysfunction i.e., congestive nephropathy is often overlooked in comparison to the forward flow hypothesis, which implicates inadequate cardiac output. However, multiple studies have indicated that elevated central venous pressure (CVP) is associated with deteriorating renal function, even in the presence of preserved cardiac index[10,11]. Conversely, a decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is observed in heart failure primarily in cases of extremely low cardiac output. For example, in one study, patients were categorized into three groups based on their cardiac index (CI): CI > 2.0 L/min/m2 (group A), CI: 1.5 to 2.0 L/min/m2 (group B), and CI < 1.5 L/min/m2 (group C). While all groups exhibited a decrease in the renal fraction of cardiac output and renal blood flow, a significant reduction in GFR was observed only in group C[12].

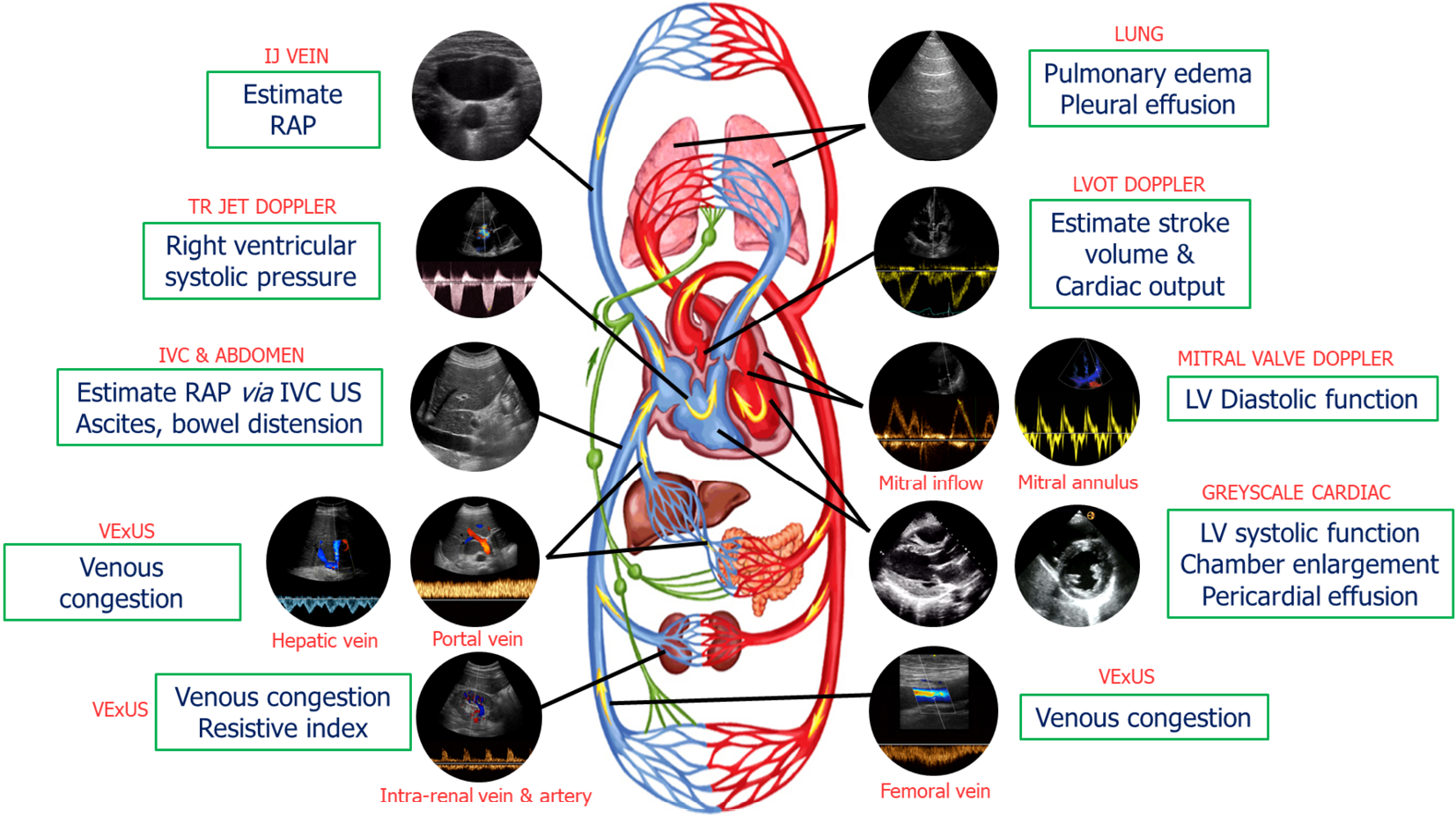

Our group has previously introduced a goal-directed POCUS strategy for hemodynamic assessment known as the pump, pipes, and the leaks[13]. The pump refers to focused cardiac ultrasound, pipes represent ultrasound evaluation of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and venous Doppler, while the leaks involve assessing extravascular lung and abdominal fluid (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Common sonographic applications used by trained clinicians at the bedside in the evaluation of acute kidney injury.

It is important to evaluate multiple points of the hemodynamic circuit instead of relying on isolated parameters. IJ: Internal jugular; RAP: Right atrial pressure; TR: Tricuspid regurgitation; IVC: Inferior vena cava; US: Ultrasound; VExUS: venous excess ultrasound; LV: Left ventricular; LVOT: Left ventricular outflow tract. Citation: Koratala A, Reisinger N. Point of Care Ultrasound in Cirrhosis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: Beyond Inferior Vena Cava. Kidney360 2022; 3: 1965-1968. Copyright© 2022 by the American Society of Nephrology (corresponding author’s prior open access publication).

The pump

The performance and efficiency of the heart directly impact blood flow, organ perfusion, and function. As such, a comprehensive hemodynamic assessment involves evaluation of various cardiac parameters that determine forward flow as well as backward congestion. A subjective assessment of left ventricular (LV) size and motion can provide a qualitative estimate of ejection fraction (EF). This eyeballing method has proven to be reasonably accurate when performed by non-cardiologists with minimal training[14]. Additionally, other parameters such as pericardial effusion, valvular dysfunction, and chamber enlargement can be evaluated. Right ventricular (RV) enlargement and interventricular septal flattening are associated with volume overload and/or pressure overload, resulting in a D-shaped LV appearance in the parasternal short axis cardiac view. RV enlargement is often accompanied by functional tricuspid regurgitation, which further contributes to RV overload and increased right atrial pressure (RAP), which can be estimated by IVC POCUS[15,16]. Nephrologists trained in Doppler applications can assess stroke volume at the bedside by measuring LV outflow tract velocity time integral (LVOT VTI) providing insight into cardiac index, which can be used to distinguish between hypovolemia and euvolemia and low vs high cardiac output states (allows for differentiation between patients who would benefit from intravenous fluids and those who require vasopressors or inotropes). In select patients, LVOT VTI can also be used to determine fluid responsiveness, potentially avoiding excessive fluid administration. Furthermore, ability to perform Doppler POCUS enables the evaluation of LV filling pressures, aiding in the titration of diuretic therapy in outpatient settings. For example, in a study involving 1135 patients with heart failure with reduced EF, the group whose management was guided by assessing LV filling pressures and B-type natriuretic peptide levels exhibited a lower incidence of death [hazard ratio (HR): 0.45, P < 0.0001] and death or worsening renal function (HR: 0.49, P < 0.0001) compared to the standard care group during a median follow-up period of 37.4 mo[17]. Similarly, RV outflow tract Doppler and trans-tricuspid Doppler measurements offer valuable information on pulmonary artery pressures and may help distinguish between precapillary and postcapillary pulmonary hypertension[18-20]. By combining the measurement of LVOT VTI with these Doppler assessments, we can potentially identify patients with AKI who would benefit from further volume removal vs those who may require pulmonary vasodilator therapy. This approach allows for a more targeted and individualized treatment strategy based on the specific hemodynamic profile of each patient.

The pipes

IVC ultrasound: Estimating RAP using IVC size and collapsibility is a standard component of comprehensive echocardiography. In spontaneously breathing patients, the current guidelines recommend the following stratification for RAP. If the maximal anteroposterior diameter of IVC is less than 2.1 cm with more than 50% collapse during a sniff, RAP is estimated to be around 3 mmHg (ranging from 0 to 5 mmHg). If the IVC is larger than 2.1 cm and exhibits less than 50% collapse, RAP is recorded as 15 mmHg (ranging from 10 to 20 mmHg). In cases where the IVC parameters do not align with this classification, an intermediate value of 8 mmHg (ranging from 5 to 10 mmHg) is assigned. However, the correlation between IVC parameters and RAP measured through right heart catheterization is modest at best and may not be applicable to mechanically ventilated patients[21-23]. It is also unreliable in conditions such as intraabdominal hypertension. Moreover, IVC POCUS is susceptible to various technical challenges such as cylinder effect, limiting its practical usefulness, particularly when interpreted in isolation[24]. Nevertheless, the assessment of IVC can still serve as an indicator of fluid tolerance, as an engorged IVC often indicates elevated RAP in patients with a high likelihood of fluid overload. In other words, such patients have increased right-sided filling pressures and may not tolerate intravenous fluid administration.

Alternatives to IVC ultrasound: POCUS of other systemic veins such as the internal jugular vein (IJV) and superior vena cava (SVC) can be utilized for non-invasive estimation of RAP, particularly when the IVC is not accessible or unreliable (e.g., liver disease, abdominal surgery). Most clinicians are familiar with estimating jugular venous pressure through visual inspection of IJV, but it lacks sensitivity; the use of POCUS enables improved identification of the vein. In a recent study, an IJV maximal diameter of ≥ 1.2 cm or respiratory variation in diameter of < 30% showed specificity > 70% for elevated filling pressure (RAP ≥ 10 mmHg). Combining IJV POCUS with physical examination improved the combined specificity to 97% for RAP ≥ 10 mmHg[25]. In another study, less than 17% increase in the cross-sectional area of the right IJV with Valsalva maneuver predicted an elevated RAP (> 12 mmHg) with 90% sensitivity and 74% specificity[26]. In patients with cirrhosis, Leal-Villarreal et al[27] found that IJV POCUS predicts RAP better than IVC. Interestingly, satisfactory IVC images were not attainable in 18% of the cases[27]. SVC provides comparable information about RAP since it is another vessel that enters the right atrium like IVC. However, it’s not routinely used in point of care settings as transesophageal echocardiography is generally needed to obtain reliable images of the vessel. Nevertheless, Doppler ultrasound of the SVC through the subcostal transthoracic window is emerging as a viable alternative[28].

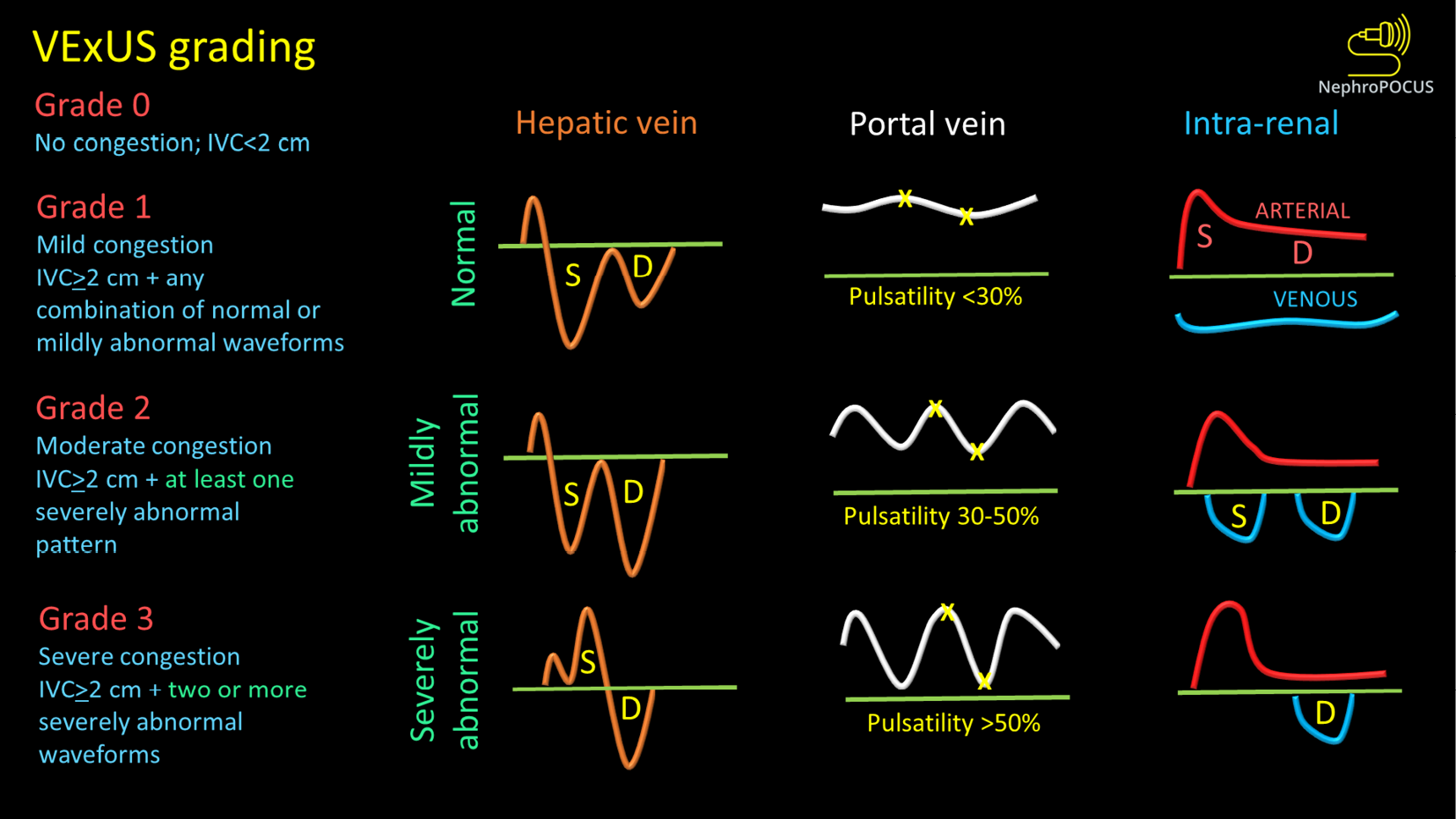

Venous congestion assessment by Doppler ultrasound: The assessment of Doppler patterns in abdominal veins has been a subject of study for several decades. However, it was not until 2020 that Beaubien-Souligny et al[29] introduced the concept of venous excess ultrasound or Venous Excess Doppler UltraSound (VExUS), which has significantly transformed our noninvasive evaluation of congestion at the bedside. Among their group of patients who underwent cardiac surgery, it was observed that the occurrence of significant flow abnormalities in two or more veins (hepatic, portal, and kidney parenchymal veins) combined with an enlarged IVC (≥ 2 cm) proved to be a more effective predictor of AKI risk (HR: 3.69; 95%CI: 1.65-8.24; P = 0.001) compared to isolated CVP measurements[29]. In other words, direct assessment of venous congestion using Doppler ultrasound offers more comprehensive information regarding congestive organ injury compared to isolated ultrasound of the IVC or IJV. Additionally, since these waveforms are dynamic in nature, VExUS serves as a valuable bedside tool for monitoring the effectiveness of decongestive therapy in real time[30-32]. Figure 2 depicts the transformation of individual Doppler waveforms with increasing RAP as well as the VExUS grading system. It is important to highlight that VExUS is not limited to cardiac surgery or heart failure patients. A recent study by Rihl et al[33] demonstrated its applicability in an unselected cohort of patients admitted to the medical intensive care unit. The study found that patients who had reduction in their VExUS score through decongestive therapy had a significantly higher number of days free from renal replacement therapy at Day 28 compared to those who did not achieve a reduction (28 vs 15, P = 0.012). Moreover, CVP alone was unable to distinguish between patients with no/mild congestion and those with severe congestion[33]. VExUS is determined by both RAP and venous compliance, making it a comprehensive measure of venous congestion. Merely measuring RAP alone does not necessarily provide information about the extent of venous congestion.

Figure 2 VexUS (Venous Excess Doppler UltraSound) grading system: When the diameter of inferior vena cava is > 2 cm, three grades of congestion are defined based on the severity of abnormalities on hepatic, portal, and renal parenchymal venous Doppler.

Hepatic vein Doppler is considered mildly abnormal when the systolic (S) wave is smaller than the diastolic (D) wave, but still below the baseline; it is considered severely abnormal when the S-wave is reversed. Portal vein Doppler is considered mildly abnormal when the pulsatility is 30% to 50%, and severely abnormal when it is ≥ 50%. Asterisks represent points of pulsatility measurement. Renal parenchymal vein Doppler is mildly abnormal when it is pulsatile with distinct S and D components, and severely abnormal when it is monophasic with D-only pattern. Figure adapted from NephroPOCUS.com with permission (corresponding author’s educational website)-https://nephropocus.com/2021/10/05/vexus-flash-cards/.

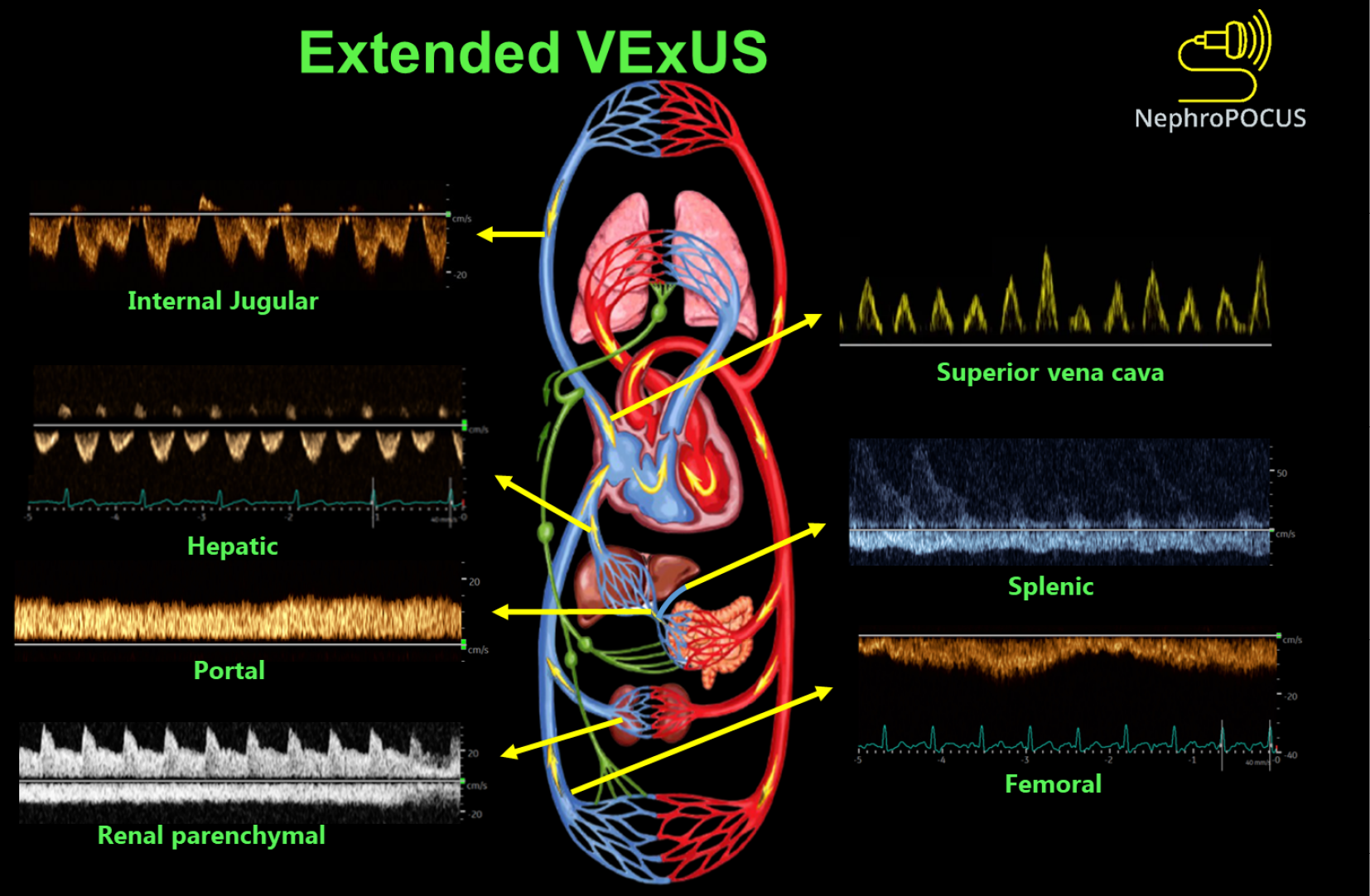

Extended VExUS: The concept of E-VExUS, or extended VExUS, has been introduced to incorporate Doppler evaluation of additional veins like the internal jugular, SVC, splenic, and femoral veins[34]. Figure 3 depicts components of E-VExUS. This extension is particularly useful when the primary veins have certain limitations (such as hepatic and portal veins in cirrhosis or intrarenal veins in advanced kidney disease). Like the components of the original VExUS, these veins have also been studied individually and demonstrated their usefulness in identifying elevated RAP[28,35-38]. Lately, there has been a surge in interest regarding femoral vein Doppler because of its relatively straightforward image acquisition process. In a recent study, the accuracy of both VExUS score and femoral vein Doppler in detecting venous congestion was reported as 80.37 (95%CI: 71.5-87.4) and 74.7 (95%CI: 65.4-82.6), respectively[39]. Nevertheless, the use of E-VExUS is still in the early phases of implementation, and further data are required to determine its clinical utility in routine practice.

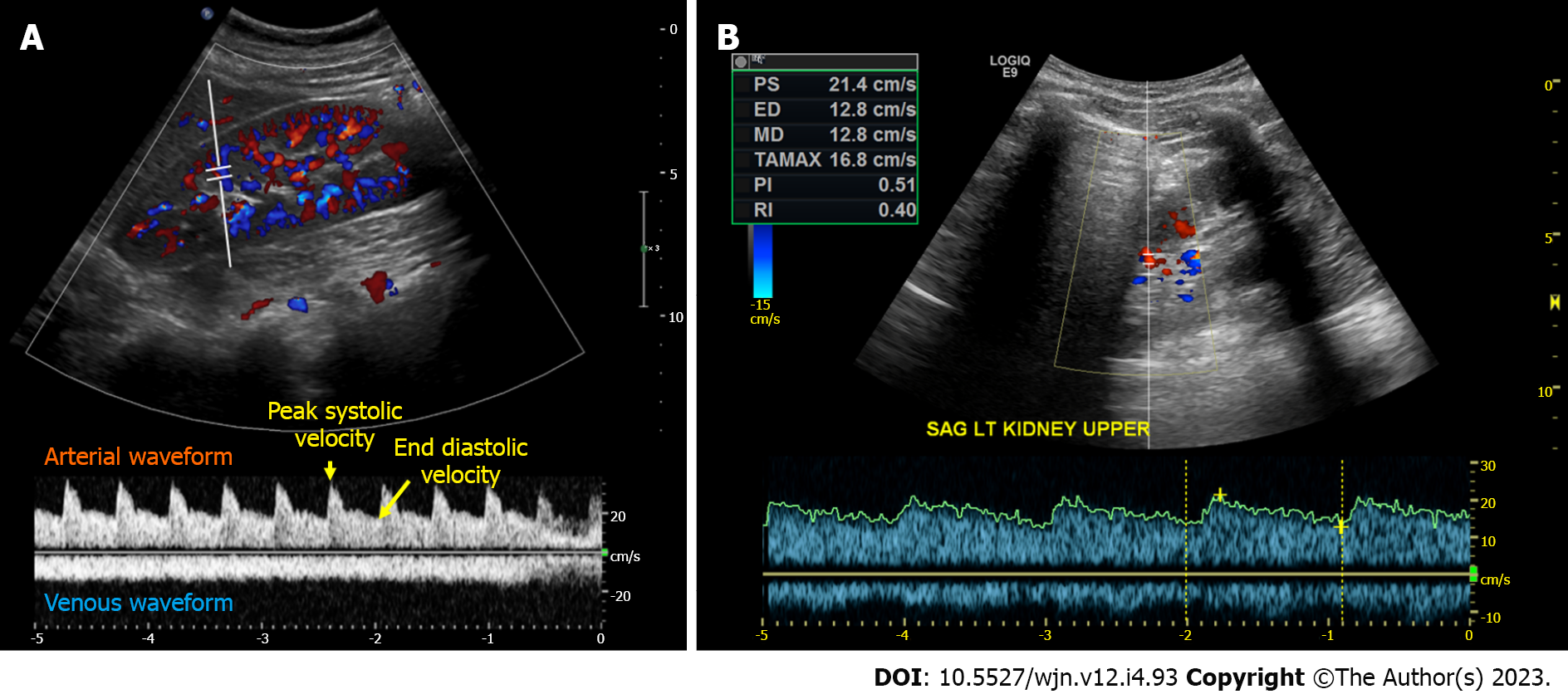

Renal arterial resistive index: In principle, the measurement of intra-renal arterial resistive index (RI) is an appealing method to assess renal perfusion, and it has been studied in various clinical scenarios such as heart failure, septic shock, and hepatorenal syndrome, showing some usefulness[40-43]. The RI is calculated using the formula (peak systolic velocity-end diastolic velocity)/peak systolic velocity within a given cardiac cycle (Figure 4A). However, the RI is influenced by multiple renal and non-renal variables including pulse pressure, heart rate, arteriosclerosis, vasoconstriction, venous congestion, underlying chronic kidney disease, valvular diseases like aortic stenosis, as well as medications, which limits its practical utility[44]. RI has also been a subject of interest in the evaluation of renal artery stenosis (RAS), but its diagnostic value remains non-specific. In our clinical practice, we rely on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance angiography to evaluate patients with uncontrolled hypertension and a high suspicion for RAS instead of POCUS. However, in some cases of RAS, a Tardus parvus waveform may be noted by the POCUS-performing physician, which should prompt further investigation. It is characterized by a slow upstroke and rounding of the systolic peak, relatively specific for RAS when found, resulting from proximal stenosis and reduced blood flow (Figure 4B). Additionally, based on our experience, there is significant variability both between different operators and within the same operator when reporting the RI, making it less reliable for monitoring response to therapeutic interventions in the point of care settings. Moreover, intrarenal Doppler in general is technically challenging to perform in critically ill patients. On the contrary, intra-renal venous Doppler is a more reproducible and less error-prone method due to its qualitative nature, which involves waveform analysis without the requirement for precise measurements. Moreover, venous congestion may explain the elevated RI observed in patients with volume overload, as it increases the resistance to arterial diastolic flow.

Figure 4 Intrarenal Doppler demonstrating normal waveforms, Tardus Parvus waveform in a case of renal artery stenosis.

A: Normal waveforms; B: Tardus Parvus waveform.

The leaks

POCUS is a sensitive bedside tool to detect extravascular lung water and ascites, both of which have important management implications in the treatment of AKI (e.g., determine the amount of ultrafiltration in patients requiring renal replacement therapy, titrate diuretic dosing, gauge fluid tolerance when contemplating intravenous fluid therapy or assess the need for therapeutic paracentesis). In a systematic review and meta-analysis including a total of 8 studies reporting on 2787 patients, lung POCUS was found to be more sensitive (91.8% vs 76.5%) and specific (92.3% vs 87.0%) than chest radiography for the detection of cardiogenic pulmonary edema[45]. Similarly, lung POCUS has been shown to detect small pleural effusions with a higher diagnostic accuracy than lateral decubitus chest radiography[46]. With respect to ascites, the superiority of ultrasound to physical examination and radiography has been long recognized[47]. Notably, unlike Doppler ultrasound, both these sonographic applications are much easier to learn with short training.

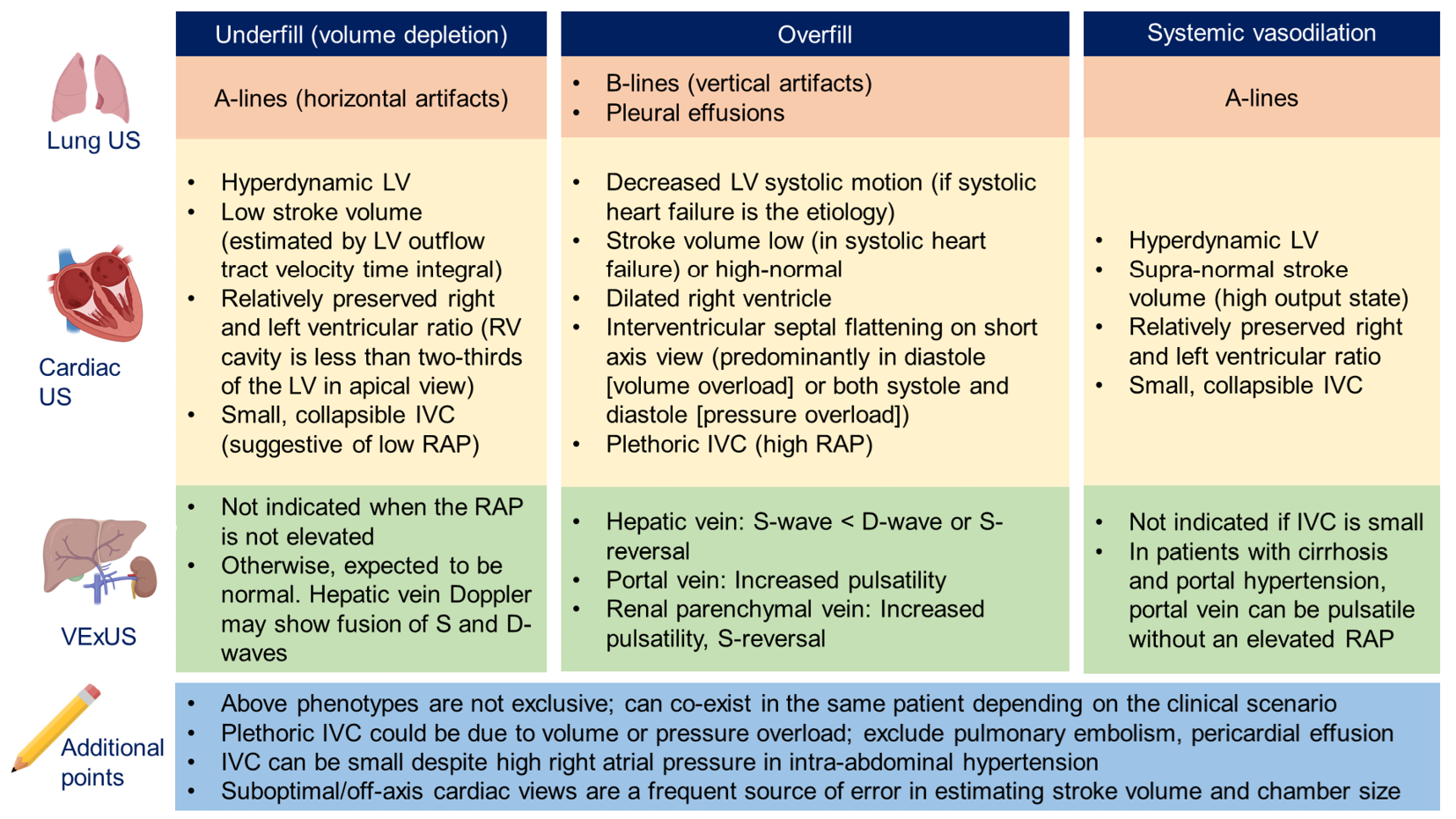

Figure 5 provides an Overview of common ultrasound findings in nephrology-relevant hemodynamic phenotypes.

Figure 5 Overview of common ultrasound findings in nephrology-relevant hemodynamic phenotypes.

Systemic vasodilation is frequently seen in patients with liver cirrhosis or early sepsis and renal dysfunction. Underfill phenotype primarily denotes volume depletion. IVC: Inferior vena cava; LV: Left ventricle; RAP: Right atrial pressure; US: Ultrasound; VExUS: Venous excess Doppler ultrasound. Citation: Taleb Abdellah A, Koratala A. Nephrologist-Performed Point-of-Care Ultrasound in Acute Kidney Injury: Beyond Hydronephrosis. Kidney Int Rep 2022; 7: 1428-1432. Copyright© 2022 International Society of Nephrology. Published by Elsevier Inc. (corresponding author’s prior open access publication).

POCUS IN INTRINSIC RENAL AKI

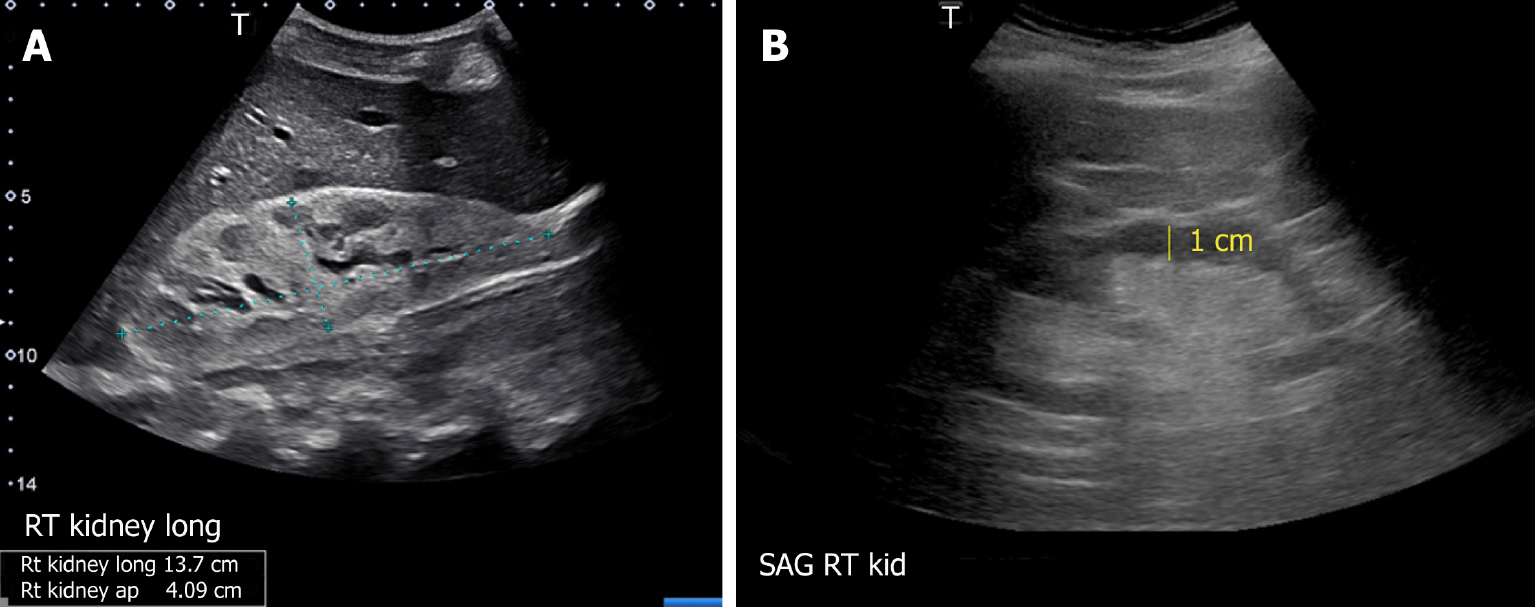

The usefulness of POCUS in determining the underlying cause of intrinsic AKI is limited. Parameters such as cortical echogenicity, thickness and renal length can provide some insights when considered in the appropriate clinical context but lack specificity (Figure 6)[48]. For instance, in cases where the baseline serum creatinine is unavailable, a small kidney size and increased cortical echogenicity may suggest a lower likelihood of treatable disease[49]. Conversely, enlarged kidneys with preserved parenchymal thickness and increased cortical echogenicity must prompt further investigation for infiltrative diseases like amyloidosis and malignancy, although these findings alone are not diagnostic. Of note, increased cortical echogenicity is seen in any renal parenchymal disease, regardless of acute or chronic process (e.g., acute tubular necrosis, acute interstitial nephritis, acute glomerulonephritis, and chronic kidney disease)[50].

Figure 6 Renal sonogram demonstrating (A) large hyperechogenic kidney in a patient with multiple myeloma and (B) thin parenchyma approximately 1 cm in a patient with chronic kidney disease (normal parenchymal thickness: 1.5-2 cm).

Citation: Koratala A, Bhattacharya D, Kazory A. Point of care renal ultrasonography for the busy nephrologist: A pictorial review. World J Nephrol 2019; 8: 44-58. Copyright© The Author(s) 2019. Published by Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. (corresponding author’s prior open access publication).

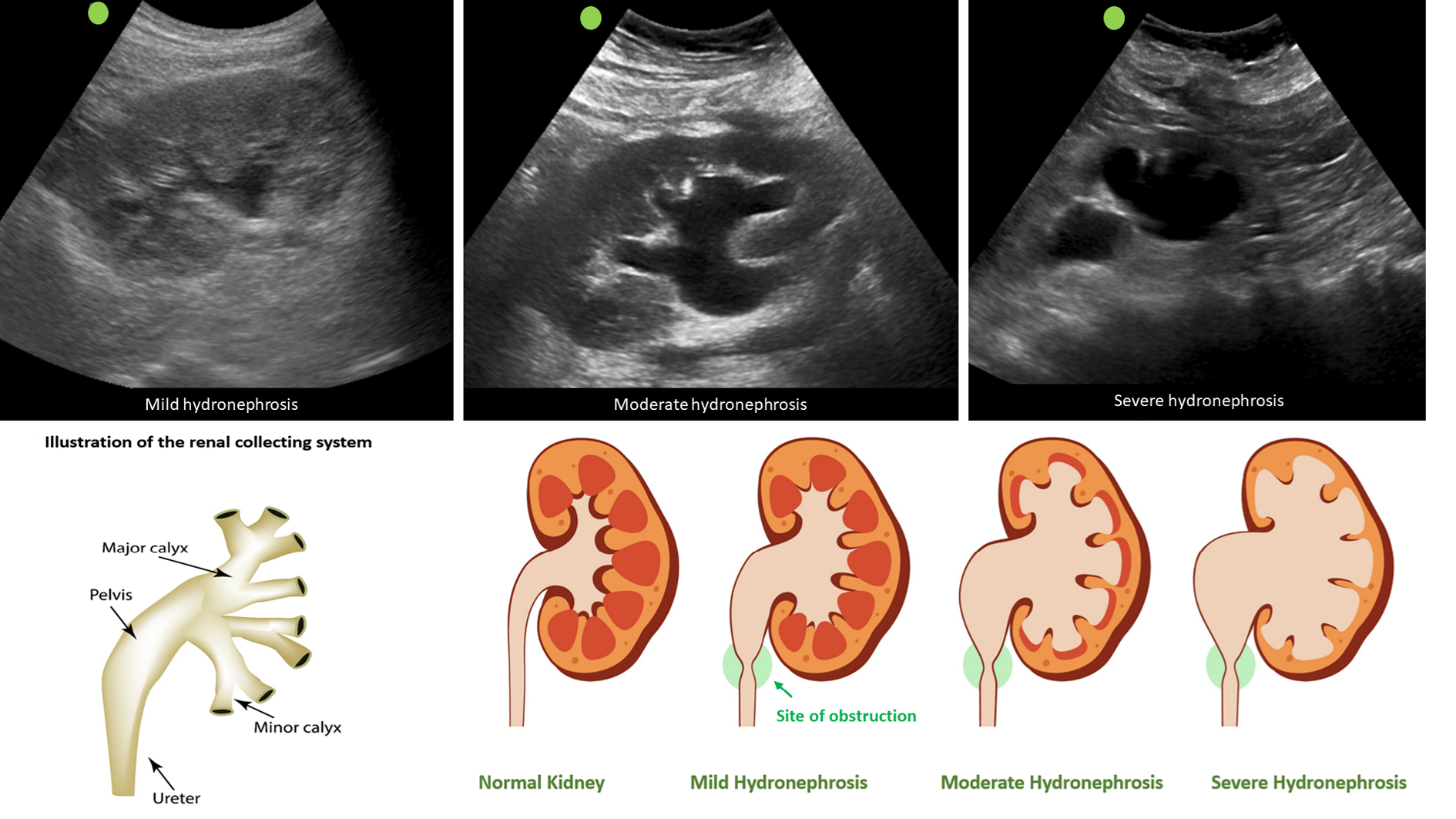

POCUS IN OBSTRUCTIVE AKI

Clinicians skilled in POCUS can easily identify urinary obstruction through bedside POCUS, leading to prompt diagnosis and timely intervention to relieve the obstruction, thereby preventing a decline in GFR. In one study, internist-performed POCUS demonstrated a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 100% for urinary tract obstruction in patients with AKI. Furthermore, the negative predictive value was 99%, indicating that it is a valuable tool that can potentially reduce the need for departmental ultrasound[51]. Similarly, in a study performed in the emergency setting, when compared to the consensus radiology interpretation of POCUS as the reference standard, emergency physicians demonstrated an overall sensitivity of 85.7% (95%CI: 84.3%-87.0%), specificity of 65.9% (95%CI: 63.1%-68.7%), positive likelihood ratio of 2.5 (95%CI: 2.3-2.7), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.22 (95%CI: 0.19-0.24) for detecting hydronephrosis[52]. On a note of caution, novice POCUS users should be aware of common ultrasound findings that can mimic hydronephrosis, including parapelvic cysts, extrarenal pelvis, and vascular malformations[53]. Figure 7 illustrates sonographic appearance of hydronephrosis and its qualitative grading. POCUS also allows timely identification of urinary bladder abnormalities such as urine retention, blocked or misplaced Foley catheter, urinary stones, masses, and prostatomegaly[50].

CONCLUSION

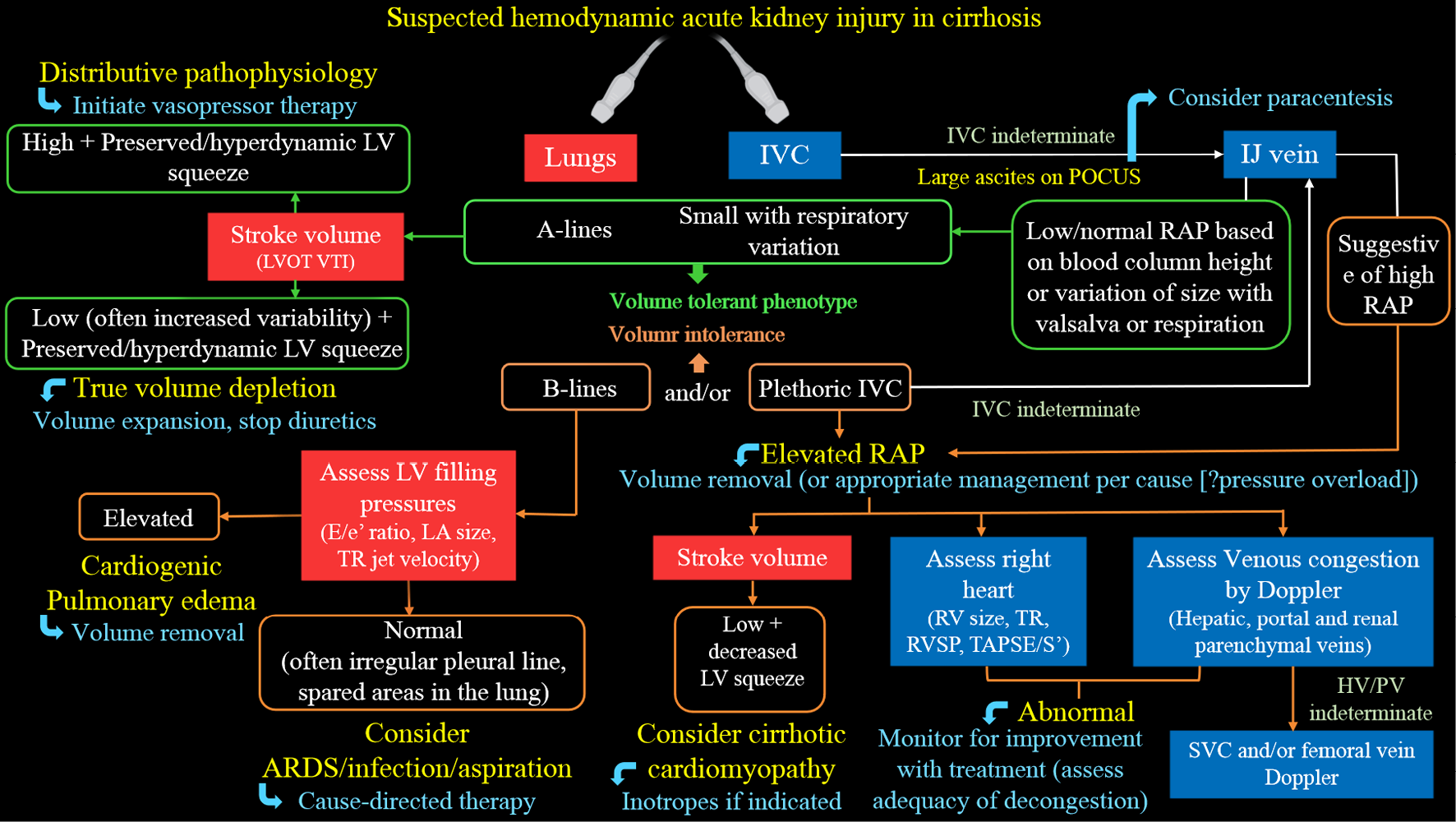

Multi-organ POCUS serves as a valuable complement to physical examination when evaluating AKI. While the use of POCUS by nephrologists has gained attention, several practical challenges exist. Currently, only a small number of nephrology fellowship programs provide comprehensive training in diagnostic POCUS beyond kidney ultrasound[54]. A significant barrier to widespread training is the limited availability of faculty who are proficient in ultrasound and have dedicated time for teaching. It is crucial for professional societies to collaborate in developing standardized guidelines, competency standards, and methods for ongoing training to support POCUS training in nephrology. While current studies mainly focus on initial training, additional research is needed to determine the optimal strategies for longitudinal training to maintain proficiency in POCUS skills. Additionally, while POCUS examinations ideally only take a few extra minutes, the cumulative time burden for physicians with heavy patient loads should be considered. Another priority is the development of practical POCUS protocols tailored to specific areas of clinical need, such as the evaluation of hyponatremia, hepatorenal syndrome, and cardiorenal syndrome. For example, Figure 8 presents a sample protocol outlining the evaluation of patients with hepatorenal dysfunction using the aforementioned sonographic applications[55]. This protocol serves as a visual guide, illustrating the step-by-step approach for utilizing POCUS in guiding management of these patients. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that performing POCUS without proper training or overestimating one’s skills, as well as the capabilities of the equipment, can potentially lead to misdiagnosis and patient harm.

Figure 8 Proposed diagnostic algorithm for approaching acute kidney injury in a patient with cirrhosis.

Citation: Koratala A, Reisinger N. Point of Care Ultrasound in Cirrhosis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: Beyond Inferior Vena Cava. Kidney360 2022; 3: 1965-1968. Copyright© 2022 by the American Society of Nephrology (corresponding author’s prior open access publication).