Published online Aug 9, 2018. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v8.i4.102

Peer-review started: April 11, 2018

First decision: May 3, 2018

Revised: May 21, 2018

Accepted: May 30, 2018

Article in press: May 31, 2018

Published online: August 9, 2018

Processing time: 120 Days and 13.4 Hours

To evaluate the outcomes of transplanting marginal kidneys preemptively compared to better-quality kidneys after varying dialysis vintage in older recipients.

Using OPTN/United Network for Organ Sharing database from 2001-2015, we identified deceased donor kidney (DDK) transplant recipients > 60 years of age who either underwent preemptive transplantation of kidneys with kidney donor profile index (KDPI) ≥ 85% (marginal kidneys) or received kidneys with KDPI of 35%-84% (better quality kidneys that older wait-listed patients would likely receive if waited longer) after being on dialysis for either 1-4 or 4-8 years. Using a multivariate Cox model adjusting for donor, recipient and transplant related factors- overall and death-censored graft failure risks along with patient death risk of preemptive transplant recipients were compared to transplant recipients in the 1-4 and 4-8 year dialysis vintage groups.

RESUTLS

The median follow up for the whole group was 37 mo (interquartile range of 57 mo). A total of 6110 DDK transplant recipients above the age of 60 years identified during the study period were found to be eligible to be included in the analysis. Among these patients 350 received preemptive transplantation of kidneys with KDPI ≥ 85. The remaining patients underwent transplantation of better quality kidneys with KDPI 35-84% after being on maintenance dialysis for either 1-4 years (n = 3300) or 4-8 years (n = 2460). Adjusted overall graft failure risk and death-censored graft failure risk in preemptive high KDPI kidney recipients were similar when compared to group that received lower KDPI kidney after being on maintenance dialysis for either 1-4 years (HR 1.01, 95%CI: 0.90-1.14, P = 0.84 and HR 0.96, 95%CI: 0.79-1.16, P = 0.66 respectively) or 4-8 years (HR 0.82, 95%CI: 0.63-1.07, P = 0.15 and HR 0.81, 95%CI: 0.52-1.25, P = 0.33 respectively). Adjusted patient death risk in preemptive high KDPI kidney recipients were similar when compared to groups that received lower KDPI kidney after being on maintenance dialysis for 1-4 years (HR 0.99, 95%CI: 0.87-1.12, P = 0.89) but lower compared to patients who were on dialysis for 4-8 years (HR 0.74, 95%CI: 0.56-0.98, P = 0.037).

In summary, our study supports accepting a “marginal” quality high KDPI kidney preemptively in older wait-listed patients thus avoiding dialysis exposure.

Core tip: Increasing waiting-time for deceased donor kidney (DDK) transplantation adversely impacts older patients disproportionately. Dialysis vintage and transplantation of “marginal kidneys” are associated with inferior post-transplant outcomes. Using OPTN/United Network for Organ Sharing database from 2001-2015, we compared the outcomes of preemptive transplantation of marginal [kidney donor profile index (KDPI) ≥ 85%] DDKs compared to transplanting better quality DDKs (KDPI 35%-84%) after being on dialysis for 1-4 and 4-8 years in patient > 60 years old. Preemptive transplantation of marginal kidneys provided non-inferior graft and patient outcomes compared to transplanting better quality kidneys in older patients on maintenance dialysis. Early transplantation could also provide quality of life and cost benefits.

- Citation: Chopra B, Sureshkumar KK. Kidney transplantation in older recipients: Preemptive high KDPI kidney vs lower KDPI kidney after varying dialysis vintage. World J Transplant 2018; 8(4): 102-109

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v8/i4/102.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v8.i4.102

Number of patients waiting for kidney transplantation has been steadily growing in the United States with nearly 100000 currently on the waiting list. Organ shortage is the major limiting factor. With the intention to optimize utilization of deceased donor kidneys (DDKs), Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) implemented the new kidney allocation system (KAS) in December 2014[1]. In the new KAS, each kidney is allocated a kidney donor profile index (KDPI) based on 10 donor variables. KDPI is derived from the prediction model termed kidney donor risk index (KDRI) which was originally proposed by Rao et al [2] in 2009. KDPI score ranges from 0%-100% with higher scores meaning lower quality kidneys. For instance, a KDPI score of 85% means that the kidney quality is worse than 85% of kidneys recovered for transplantation during the previous calendar year. The new KAS promotes allocation of better quality kidneys to recipients with better estimated post-transplant survival in a concept called longevity matching[3]. On the other hand, kidneys with higher KDPI are likely offered to older recipients.

Preemptive transplantation (transplantation before the need for maintenance dialysis) has been shown to be associated with better post-transplant outcomes[4,5]. Dialysis vintage is an independent predictor of adverse long-term outcomes following both deceased and living donor kidney transplantation[6-9]. Kidneys with KDPI ≥ 85% are considered “marginal” and transplantation of such organs are associated with inferior outcomes when compared to transplanting kidneys with lower KDPI[10]. It is unclear whether preemptive transplantation of high KDPI kidneys and thus avoiding maintenance dialysis in older recipients would be beneficial compared to waiting for and transplanting lower KDPI kidneys after being on dialysis for varying lengths of time. We sought to answer this by utilizing the national transplant database.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 2000 Declaration of Helsinki as well as 2008 Declaration of Istanbul. Using OPTN/United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database, we identified patients older than 60 years who underwent first time DDK transplantation between January 2001 and December 2015, after receiving perioperative antibody induction and discharged on a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) and Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) based maintenance immunosuppression. From this group, we further identified patients who underwent preemptive transplantation with kidneys with KDPI ≥ 85% and those who underwent transplantation of kidneys with KDPI of 35%-84% after being on maintenance dialysis for either 1-4 years or 4-8 years. We chose KDPI of 35%-84% in the dialysis groups in order to approximate real life scenarios since older patients who wait longer will likely get offer for DDKs with mid-range quality with new KAS. KDPI was calculated retrospectively by OPTN/UNOS and is available in their database. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they received previous transplant, underwent live donor kidney, or multi-organ transplantation. Patients were also excluded if they received no induction or were on maintenance regimen other than CNI/MMF.

Demographic variables for the three groups were collected. Overall and death-censored graft failure risks along with patient death risk associated with preemptive transplantation of high KDPI (≥ 85%) kidneys were compared to these outcomes associated with transplantation of lower KDPI (35%-84%) kidneys among recipients who were on maintenance dialysis for 1-4 years and 4-8 years after correcting for pre-specified variables. The covariates used for correction in the multivariate model were: donor related including age, gender, expanded criteria donor kidney, donation after cardiac death kidney, cause of donor death; recipient related including age, African American race, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B and C sero-positivity, ESRD cause, dialysis duration, panel reactive antibody (PRA) titer (peak PRA till 2009 and calculated PRA from 2009 onwards), human leukocyte antigen mismatch; transplant related including type of induction, cold ischemia time, pump perfusion of kidney, delayed graft function (defined as need for dialysis within the first week of transplantation), steroid maintenance, and transplant year.

Continuous variables were compared between groups using 2-tailed t-tests and categorical variables were compared using χ2 test. Values were expressed as either mean ± standard deviation or as percentages. Missing values were addressed by imputing means of the variables. Cox model was used to compare adjusted graft and patient outcomes between the groups. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 18 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States).

The median follow up for the whole group was 37 mo (interquartile range of 57 mo). A total of 6110 DDK transplant recipients above the age of 60 years identified during the study period were found to be eligible to be included in the analysis. Among these patients 350 received preemptive transplantation of kidneys with KDPI ≥ 85. The remaining patients underwent transplantation of better quality kidneys with KDPI 35%-84% after being on maintenance dialysis for either 1-4 years (n = 3300) or 4-8 years (n = 2460).

The demographic features of the different groups are shown in Table 1. Preemptively transplanted kidneys had a KDPI of 93% ± 4% while the KDPI were 62% ± 14% and 62% ± 9% in patients who received the transplant after being on dialysis for 1-4 years and 4-8 years respectively. Mean dialysis duration was 31 ± 10 mo and 67 ± 13 mo respectively in patient groups with dialysis duration 1-4 years and 4-8 years. As shown there were significant differences between the preemptive transplant group and groups that received kidney transplant after being on maintenance dialysis. In the preemptive transplant group, donor age was higher with fewer male donors along with fewer donation after cardiac death (DCD) and more expanded criteria donor (ECD) kidneys; recipients were older with fewer males, African Americans, and diabetics. Preemptive group also had higher proportion of kidneys pump perfused, lower PRA, higher HLA mismatches, lower DGF rates and lower steroid maintenance rates.

| Preemptive-high KDPI(n = 350) | 1-4 yr dialysis vintage-lower KDPI (n = 3300) | Preemptive-high KDPI(n = 350) | 4-8 yr dialysis vintage-lower KDPI (n = 2460) | |

| KDPI | 93 ± 4 | 62 ± 14 | 93 ± 4 | 62 ± 9 |

| Dialysis duration (mo) | 0 | 31 ± 10 | 0 | 67 ± 13 |

| Age (donor) | 61 ± 12 | 46 ± 13b | 61 ± 12 | 46 ± 14b |

| Donor gender (M) % | 46.8 | 56d | 46.8 | 54.3a |

| DCD kidney (%) | 8.6 | 14.4d | 8.6 | 14.9d |

| ECD kidney (%) | 89.4 | 25.6b | 89.4 | 26b |

| HLA mismatch | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 3.9 ± 1.7b | 4.5 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 1.4a |

| Recipient age (years ± SD) | 69 ± 5 | 67 ± 4a | 69 ± 5 | 67 ± 4b |

| Recipient gender (M) % | 52.4 | 63.5b | 52.4 | 64b |

| African American Recipient (%) | 14.7 | 20.9a | 14.7 | 30.8b |

| Recipient diabetes (%) | 30.4 | 51b | 30.4 | 52.5b |

| Recipient BMI (%) | 27 ± 4 | 28 ± 5a | 27 ± 4 | 28 ± 5 |

| Calculated PRA | 4.6 ± 14 | 10 ± 25b | 4.6 ± 14 | 13 ± 27b |

| Cold ischemia time (h) | 19 ± 8 | 18 ± 9 | 19 ± 8 | 18 ± 9 |

| Delayed graft function (%) | 5.3 | 29b | 5.3 | 37.5b |

| Depleting induction (%) | 65.5 | 69.8 | 65.5 | 71.5a |

| Steroid maintenance (%) | 64 | 69.6a | 64 | 70.2a |

| Kidney pumped (%) | 53.7 | 42.2b | 53.7 | 44d |

| Transplant year | 2009 ± 4 | 2008 ± 4a | 2009 ± 4 | 2010 ± 3b |

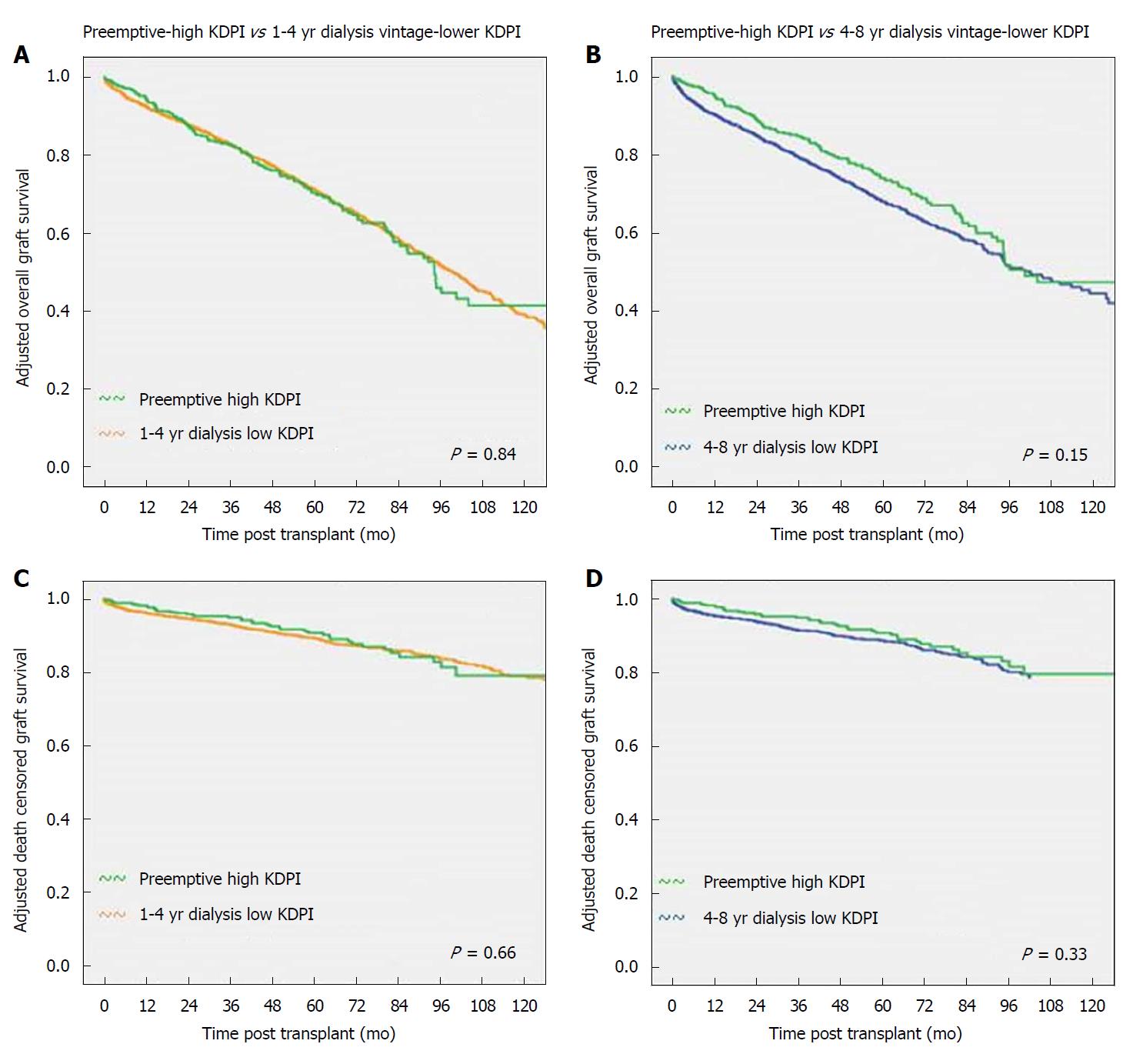

Adjusted overall graft and death-censored graft survivals of preemptive high KDPI kidney recipients compared to recipients of lower KDPI kidneys with 1-4 years and 4-8 years dialysis vintage is shown in Figure 1. Adjusted overall graft failure risk and death-censored graft failure risk in preemptive high KDPI kidney recipients were similar when compared to group that received lower KDPI kidney after being on maintenance dialysis for either 1-4 years (HR 1.01, 95%CI: 0.90-1.14, P = 0.84 and HR 0.96, 95%CI: 0.79-1.16, P = 0.66 respectively) or 4-8 years (HR 0.82, 95%CI: 0.63-1.07, P = 0.15 and HR 0.81, 95%CI: 0.52-1.25, P = 0.33 respectively) as shown in Table 2.

| Preemptive-high KDPI (n = 349) vs 1-4 yrdialysis vintage-lower KDPI (n = 3300) | Preemptive-high KDPI (n = 349) vs 4-8 yrdialysis vintage-lower KDPI (n = 2460) | |||

| Adjusted overall graft failure risk | 1.01 (0.90-1.14) | 0.84 | 0.82 (0.63-1.07) | 0.15 |

| Adjusted death censored graft failure risk | 0.96 (0.79-1.16) | 0.66 | 0.81 (0.52-1.25) | 0.33 |

| Adjusted patient death risk | 0.99 (0.87-1.12) | 0.89 | 0.74 (0.56-0.98) | 0.04 |

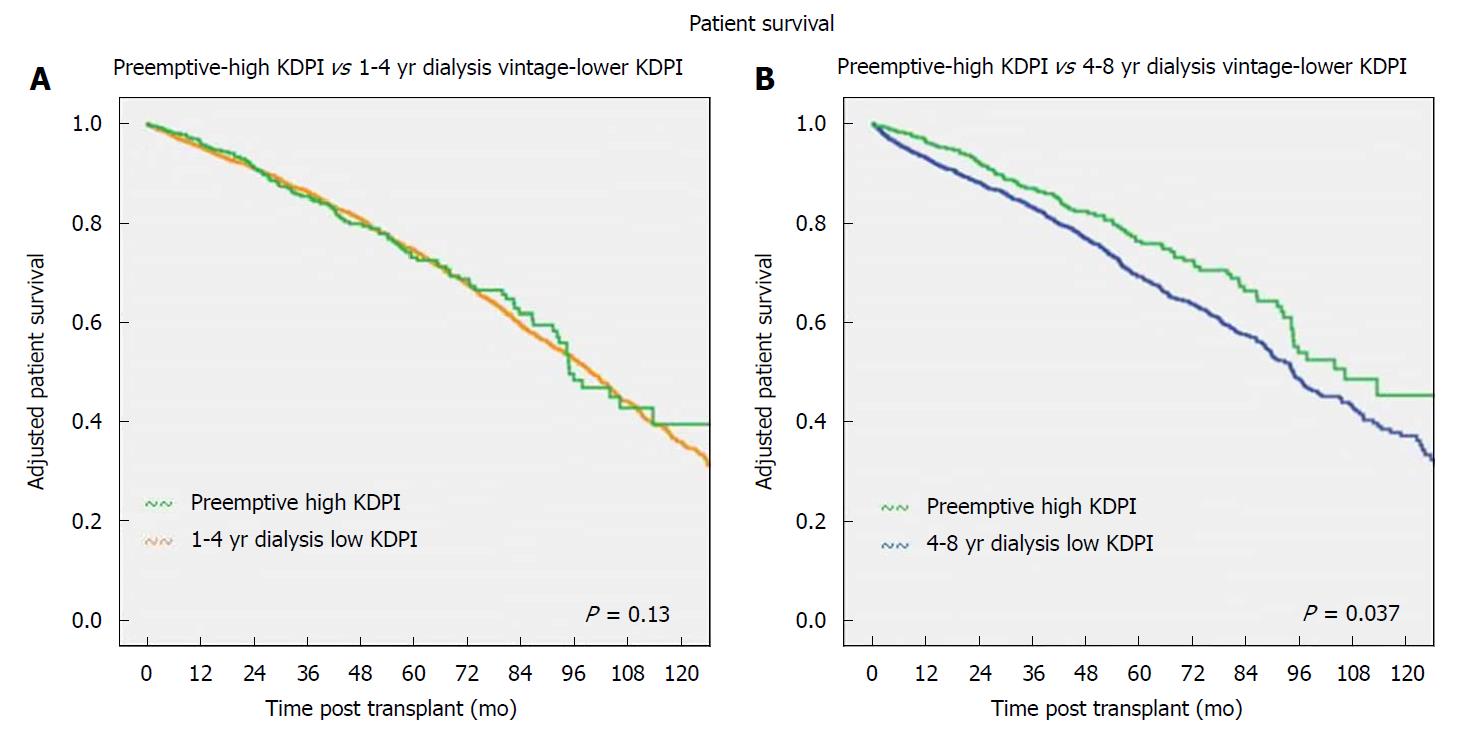

Adjusted patient survival of preemptive high KDPI kidney recipients compared to recipients of lower KDPI kidneys with 1-4 years and 4-8 years dialysis vintage are shown in Figure 2. Adjusted patient death risk in preemptive high KDPI kidney recipients were similar when compared to groups that received lower KDPI kidney after being on maintenance dialysis for 1-4 years (HR 0.99, 95%CI: 0.87-1.12, P = 0.89) but lower compared to patients who were on dialysis for 4-8 years (HR 0.74, 95%CI: 0.56-0.98, P = 0.04) as shown in Table 2.

Our study showed that preemptive transplantation of high KDPI (≥ 85%) kidneys in older first-time recipients conferred graft and patient outcomes that were not inferior when compared to transplanting better quality lower KDPI (35%-84%) kidneys in older recipients who were on maintenance dialysis for variable periods of time. In fact a patient survival benefit was emerging for preemptive high KDPI kidney recipients when compared to patient who got transplanted better quality kidney after a longer dialysis vintage. Our findings support favorable consideration of “marginal” kidneys for preemptive transplantation in older patients on the waiting list.

Living donor kidney transplantation in general offers the best patient and graft survival with the benefits extending to older recipients as well[11,12]. Living donor kidneys from 60-69 years old donors transplanted into older recipients’ conferred superior patient survivals compared to standard criteria donor (SCD) and ECD DDKs while the graft survivals were superior compared to ECD but similar compared to SCD kidneys[13]. Patients without options for living donors are faced with an increasing time on the deceased donor wait list. The median time to transplant once listed has been steadily increasing, for instance from 5.5 years in 2003 to 7.6 years in 2007[11]. This is particularly disadvantageous to older wait listed patients, since longer they wait; the less likely they get transplanted since their health status can deteriorate thus running the risk of removal from the wait list or death[14]. Consideration of high KDPI kidneys can help to decrease the waiting time for such patients.

Transplantation of DDKs with high KDRI (from which KDPI is calculated) is associated with increased risk for allograft failure when compared to transplanting lower KDRI kidneys[2,10]. As mentioned, DDKs with KDPI ≥ 85% are considered as “marginal” quality organs similar to the kidneys from ECD terminology used prior to the implementation of new KAS. Transplantation of ECD kidneys have been shown to be associated with higher risk for developing DGF, longer hospital length of stay and higher readmissions rates with higher cost of care along with increased risk for graft loss and mortality[15-18]. Because of these concerns, centers could understandably be reluctant to accept marginal kidneys for preemptive transplantation in their wait listed patients who have not started maintenance dialysis yet. However, it is hard to predict how long such patients will have to wait to get offer for a more desirable kidney with a good chance that they could initiate dialysis while waiting. Our findings support the practice of careful consideration of marginal kidney offers compared to automatic decline of such kidney offers for preemptive transplantation in wait listed older recipients. This may also help to reduce the discard rate for these kidneys with KDPI ≥ 85% which was at 60% at year 2 after the implementation of new KAS according to a recent UNOS report[19].

Despite a 70% increased risk for graft failure compared to non-ECD kidneys, transplantation of ECD kidneys which are considered “marginal” was found to confer survival benefit when compared to staying on waiting list[12,20-22]. Dialysis duration has been suggested as the strongest independent modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes[8]. Increased comorbidity burden and immunological alterations that can develop in dialysis patients, along with adverse socioeconomic conditions associated with prolonged dialysis are some of the factors implicated towards inferior transplant outcomes observed in patients exposed to longer dialysis duration. Any adverse impact of transplanting high KDPI marginal kidneys in our preemptive group likely got mitigated by dialysis avoidance. On the other hand, any potential benefits of transplanting better quality lower KDPI kidneys in the dialysis groups are likely minimized by the impact of dialysis vintage on transplant outcomes. A previous analysis showed lower overall cumulative mortality associated with transplantation of high KDPI kidneys when compared to equivalent patients who forego high KDPI kidney transplantation with the hope of receiving lower KDPI kidney at a later time point while staying on dialysis[23]. Benefit was more pronounced in recipients > 50 years of age and at centers with wait time > 33 mo.

While our study demonstrated similar graft and patient outcomes for preemptive transplantation of high KDPI kidneys when compared to low KDPI kidney transplantation after varying dialysis vintage in older recipients, one also has to consider the quality of life advantage that can come with earlier transplantation. Previous studies have shown quality of life benefits in older patients who underwent kidney transplantation[24,25]. Earlier kidney transplantation could also translate into long-term cost savings. A recent economic analysis of contemporary kidney transplant practice found cost saving with living donor and low KDPI deceased donor transplants when compared to dialysis while transplantation using high KDPI DDK was cost effective[26].

Our study has limitations that merit discussion. Retrospective design only can prove associations but not causation. However, a prospective study addressing the same question will be difficult to conduct for logistical reasons. Residual confounding can still occur despite using a multivariate adjustment in our analysis. Doses or drug levels of maintenance immunosuppressive drugs and information about longitudinal changes in medication regimens which could impact transplant outcomes were not available. Even though our analysis showed favorable outcomes of preemptive transplantation of high KDPI kidneys in older recipients, this does not imply transplantability of each and every such kidney. The analysis was biased towards kidneys that actually got transplanted and kidneys may be rejected for reasons unrelated to KDPI.

In summary, our study supports accepting a “marginal” quality high KDPI kidney preemptively in older wait-listed patients thus avoiding dialysis exposure. Such preemptive transplantation results in graft and patient outcomes non-inferior to receiving a better quality kidney with lower KDPI after being on dialysis for a variable period. This practice could come with an added quality of life benefit associated with earlier transplantation and possibly cost benefit. In order to best serve such patients on the waiting list, clinicians should be open to offers of high KDPI kidneys and get the patients involved in this important and very personal decision making process.

It is unclear whether preemptive transplantation of high kidney donor profile index (KDPI) (marginal quality) kidneys and thus avoiding maintenance dialysis in older recipients would be beneficial compared to waiting for and transplanting lower KDPI (better quality donor organ) kidneys after being on dialysis for varying lengths of time. We sought to answer this by utilizing the national transplant database.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of transplanting marginal kidneys preemptively compared to better-quality kidneys after varying dialysis vintage in older recipients.

The objective of our study was to explore the benefits of transplanting marginal quality kidney preemptively compared to waiting for better quality kidney transplantation after exposure to varying times on dialysis.

Using United Network for Organ Sharing database, we identified patients > 60 years who underwent first time deceased donor kidney (DDK) transplantation between January 2001 and December 2015, after receiving induction and discharged on calcineurine inhibitor/Mycophenolate Mofetil immunosuppression. We further identified patients who underwent preemptive DDK with KDPI ≥ 85% and those who underwent DDK with KDPI of 35%-84% after being on maintenance dialysis for either 1-4 years or 4-8 years. Cox model was used to compare adjusted graft and patient outcomes between the groups. HR with 95%CI was calculated. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 18.

Adjusted overall graft failure risk and death-censored graft failure risk in preemptive high KDPI kidney recipients were similar when compared to group that received lower KDPI kidney after being on maintenance dialysis for either 1-4 years or 4-8 years. Adjusted patient death risk in preemptive high KDPI kidney recipients were similar when compared to groups that received lower KDPI kidney after being on maintenance dialysis for 1-4 years but lower compared to patients who were on dialysis for 4-8 years.

Our study supports accepting a “marginal” quality high KDPI kidney preemptively in older wait-listed patients thus avoiding dialysis exposure. In order to best serve older patients on the waiting list, clinicians should be open to offers of high KDPI kidneys and get the patients involved in this important and very personal decision making process. A pre-emptive kidney transplant- even if it is a marginal organ, could come with an added quality of life benefit associated with earlier transplantation and possibly cost benefit. It is acceptable to use marginal quality kidneys in older transplant recipients, rather than having them wait on dialysis for better quality kidney. It has been widely accepted that marginal quality organs are acceptable for use in older transplant recipients. But there has been hesitance in accepting these kidneys for recipients who are not on dialysis yet. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of avoiding dialysis vintage by preemptive transplantation of marginal kidneys in older recipients when compared to receiving better quality organ while remaining on dialysis. Avoiding dialysis with early transplantation should be favorably considered even with marginal quality kidneys. It will be logistically hard to design a prospective study trying to answer the same question; but that would be ideal. Future study should identify older patients who declined preemptive offer of marginal kidneys and went on to get better quality kidneys at a later point after being on dialysis. Control group should be older patients who accepted those marginal kidneys preemptively. Post-transplant outcomes between the 2 groups should be compared. It is acceptable to use a marginal quality kidney in an older recipient, thereby avoiding dialysis exposure. The current study supports the hypothesis of transplanting marginal quality kidney preemptively in older patients. The findings of this study enable transplant professionals to make a more informed choice when faced with the option of getting a marginal kidney offer for their older wait listed patients with chronic kidney disease who are not on dialysis yet.

Avoiding dialysis exposure with early transplant even with a marginal kidney is potentially beneficial. Future studies should look at the outcomes of older patients who turned down a marginal kidney for preemptive transplantation and received better quality kidney after exposure to variable dialysis time compared to older patients who accepted the declined marginal kidneys preemptively and thus avoided dialysis exposure. Future study should identify older patients who declined preemptive offer of marginal kidneys and went on to get better quality kidneys at a later point after being on dialysis. Control group should be older patients who accepted those marginal kidneys preemptively. Post-transplant outcomes between the 2 groups should be compared.

Accepted for presentation as a poster at the American Transplant Congress, June 2018, Seattle, WA. The data reported here have been supplied by the United Network for Organ Sharing as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by OPTN or the United States government.

| 1. | Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Policy 8: Allocation of kidneys. Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/policies/. |

| 2. | Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Guidinger MK, Andreoni KA, Wolfe RA, Merion RM, Port FK, Sung RS. A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: the kidney donor risk index. Transplantation. 2009;88:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 686] [Cited by in RCA: 833] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Chopra B, Sureshkumar KK. Changing organ allocation policy for kidney transplantation in the United States. World J Transplant. 2015;5:38-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gill JS, Tonelli M, Johnson N, Pereira BJ. Why do preemptive kidney transplant recipients have an allograft survival advantage? Transplantation. 2004;78:873-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Goto N, Okada M, Yamamoto T, Tsujita M, Hiramitsu T, Narumi S, Katayama A, Kobayashi T, Uchida K, Watarai Y. Association of Dialysis Duration with Outcomes after Transplantation in a Japanese Cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:497-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Meier-Kriesche HU, Port FK, Ojo AO, Rudich SM, Hanson JA, Cibrik DM, Leichtman AB, Kaplan B. Effect of waiting time on renal transplant outcome. Kidney Int. 2000;58:1311-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 486] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Goldfarb-Rumyantzev A, Hurdle JF, Scandling J, Wang Z, Baird B, Barenbaum L, Cheung AK. Duration of end-stage renal disease and kidney transplant outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:167-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Meier-Kriesche HU, Kaplan B. Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: a paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation. 2002;74:1377-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 555] [Cited by in RCA: 567] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mange KC, Joffe MM, Feldman HI. Effect of the use or nonuse of long-term dialysis on the subsequent survival of renal transplants from living donors. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:726-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sampaio MS, Chopra B, Tang A, Sureshkumar KK. Impact of cold ischemia time on the outcomes of kidneys with Kidney Donor Profile Index ≥85%: mate kidney analysis - a retrospective study. Transpl Int. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Gustafson SK, Stewart DE, Cherikh WS, Wainright JL, Boyle G, Snyder JJ, Kasiske BL. Kidney. Am J Transplant. 2016;16 Suppl 2:11-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gill JS, Schaeffner E, Chadban S, Dong J, Rose C, Johnston O, Gill J. Quantification of the early risk of death in elderly kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:427-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Englum BR, Schechter MA, Irish WD, Ravindra KV, Vikraman DS, Sanoff SL, Ellis MJ, Sudan DL, Patel UD. Outcomes in kidney transplant recipients from older living donors. Transplantation. 2015;99:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Schold JD, Meier-Kriesche HU. Which renal transplant candidates should accept marginal kidneys in exchange for a shorter waiting time on dialysis? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:532-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Saidi RF, Elias N, Kawai T, Hertl M, Farrell ML, Goes N, Wong W, Hartono C, Fishman JA, Kotton CN. Outcome of kidney transplantation using expanded criteria donors and donation after cardiac death kidneys: realities and costs. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2769-2774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McAdams-Demarco MA, Grams ME, Hall EC, Coresh J, Segev DL. Early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation: patient and center-level associations. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:3283-3288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sung RS, Guidinger MK, Christensen LL, Ashby VB, Merion RM, Leichtman AB, Port FK. Development and current status of ECD kidney transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2005;37-55. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Molnar MZ, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, Shah A, Huang E, Bunnapradist S, Krishnan M, Kopple JD, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Age and the associations of living donor and expanded criteria donor kidneys with kidney transplant outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:841-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | United Network for Organ Sharing. Two year analysis shows effects of kidney allocation system, 2017. Available from: https://www.transplantpro.org/news/two-year-analysis-shows-effects-of-kidney-allocation-system/. |

| 20. | Merion RM, Ashby VB, Wolfe RA, Distant DA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Metzger RA, Ojo AO, Port FK. Deceased-donor characteristics and the survival benefit of kidney transplantation. JAMA. 2005;294:2726-2733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 540] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725-1730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3684] [Cited by in RCA: 3965] [Article Influence: 146.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 22. | Rao PS, Merion RM, Ashby VB, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Kayler LK. Renal transplantation in elderly patients older than 70 years of age: results from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2007;83:1069-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Massie AB, Luo X, Chow EK, Alejo JL, Desai NM, Segev DL. Survival benefit of primary deceased donor transplantation with high-KDPI kidneys. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:2310-2316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Weber M, Faravardeh A, Jackson S, Berglund D, Spong R, Matas AJ, Gross CR, Ibrahim HN. Quality of life in elderly kidney transplant recipients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1877-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, Krueger H, Ferguson B, Wong C, Muirhead N. A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1996;50:235-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 824] [Cited by in RCA: 897] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Axelrod DA, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Irish W, Tuttle-Newhall E, Chang SH, Kasiske BL, Alhamad T, Lentine KL. An economic assessment of contemporary kidney transplant practice. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:1168-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kute VB, Shrestha BM S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW