Published online Dec 24, 2015. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v5.i4.354

Peer-review started: May 8, 2015

First decision: June 9, 2015

Revised: October 4, 2015

Accepted: November 17, 2015

Article in press: November 25, 2015

Published online: December 24, 2015

Processing time: 231 Days and 3.5 Hours

In liver haemangiomas, the risk of complication rises with increasing size, and treatment can be obligatory. Here we present a case of a 46-year-old female who suffered from a giant haemangioma causing severe portal hypertension and vena cava compression, leading to therapy refractory ascites, hyponatremia and venostasis-associated thrombosis with pulmonary embolism. The patients did not experience tumour rupture or consumptive coagulopathy. Surgical resection was impossible because of steatosis of the non-affected liver. Orthotopic liver transplantation was identified as the only treatment option. The patient’s renal function remained stable even though progressive morbidity and organ allocation were improbable according to the patient’s lab model for end-stage liver disease (labMELD) score. Therefore, non-standard exception status was approved by the European organ allocation network “Eurotransplant”. The patient underwent successful orthotopic liver transplantation 16 mo after admission to our centre. Our case report indicates the underrepresentation of morbidity associated with refractory ascites in the labMELD-based transplant allocation system, and it indicates the necessity of promptly applying for non-standard exception status to enable transplantation in patients with a severe clinical condition but low labMELD score. Our case highlights the fact that liver transplantation should be considered early in patients with non-resectable, symptomatic benign liver tumours.

Core tip: Here, we present a case of a 46-year-old woman with a giant, symptomatic, non-resectable haemangioma of the liver. The patient suffered from recurrent ascites and malnutrition. The patient finally received a liver transplant 16 mo following her initial presentation after being granted non-standard exception status. This case clearly indicates that liver transplantation must be considered early in patients with non-resectable, symptomatic benign liver tumours. Furthermore, it highlights the necessity of applying for non-standard exception status to enable transplantation in patients with a severe clinical condition but low labMELD score.

- Citation: Lange UG, Bucher JN, Schoenberg MB, Benzing C, Schmelzle M, Gradistanac T, Strocka S, Hau HM, Bartels M. Orthotopic liver transplantation for giant liver haemangioma: A case report. World J Transplant 2015; 5(4): 354-359

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v5/i4/354.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v5.i4.354

Haemangioma of the liver (HL) is a benign tumour with an estimated prevalence of up to 20%. Women are predominantly affected and the most prevalent histological subgroup is the cavernous haemangioma[1]. HL range in size from 1 to 35 cm, with a median size of 6 cm[2,3]. Liver haemangiomas with a diameter greater than 4 cm are defined as giant haemangiomas (GH). Typically the diagnosis of HL is incidental, and in asymptomatic cases, treatment is usually unnecessary[4,5].

Even GH are typically asymptomatic, but they may sometimes present with symptoms caused either by mass-effects or haemodynamic and rheological disturbances[6]. In rare cases, GH can cause life-threating complications, such as rupture or consumptive coagulopathy (Kasabach-Merrit syndrome)[1]. If HL are symptomatic or produce complications, an appropriate intervention is required. The variety of treatment options for cavernous HL include surgical management, such as enucleation, anatomic or non-anatomic resection, orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT), or when the haemangioma does not exceed a certain size, radiological approaches[7].

There are several case reports on liver transplantation as a last resort treatment for giant haemangiomas in the setting of haemorrhage[8] or Kasabach-Merrit syndrome[9-14]. Here we describe a case of a patient with a giant haemangioma of the right liver who was treated by OLT because of progressive mass effects of the tumour that finally led to therapy-refractory portal hypertension and hemodynamically relevant compression of the vena cava.

In July 2012, a 46-year-old woman was admitted to our centre with the diagnosis of a giant liver tumour. The patient had experienced a constant increase in abdominal girth and a feeling of fullness over the past three years. The patient had no history of alcohol abuse, viral hepatitis, previous malignancies, substance abuse or other hepatic risk-factors.

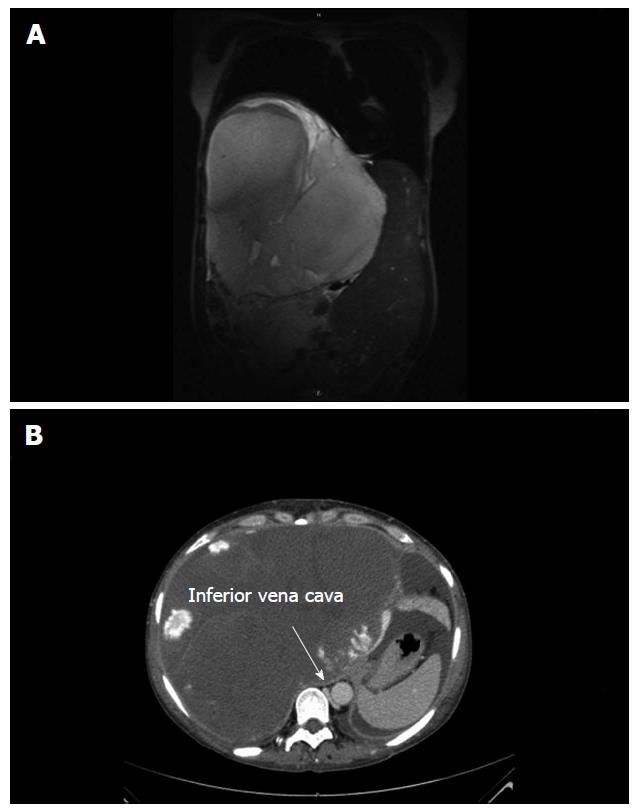

Further medical imaging showed a mass of 21.7 cm × 23.7 cm × 25.5 cm in size located primarily in the right liver lobe and involving segments IV and V-VIII. The mass showed signs of central necrosis or thrombotic degeneration. Typical for haemangioma, peripheral nodular enhancements in the arterial phase with progressive centripetal filling toward the centre in the portal venous and delayed phases were observed. Thrombosis of the right portal vein branch and stenosis of the left portal vein branch with blood malperfusion of the right and left lobe were observed. The infra-hepatic vena cava was massively dislocated to the left and slit-shaped due to compression. The tumour caused diaphragmatic elevation and a mediastinal shift to the left. The pancreas was dislocated dorsally, and the right kidney was dislocated caudally.

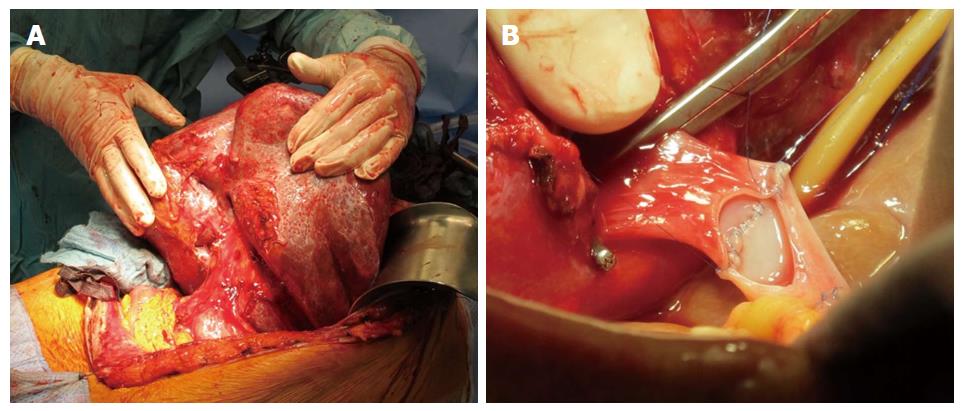

Liver enzymes, serum creatinine, and tumour markers for hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer were all within their normal ranges, and serology for viral hepatitis was also normal. Cholestasis parameters were slightly elevated (alkaline phosphatase: 2.06 μmol/L; γ-glutamyltransferase: 1.70 μmol/L). Because of the patient’s symptoms and the decrease in her quality of life, an exploratory laparotomy with the intention of tumour resection was performed in September 2012. Intraoperatively the planned liver-remnant, which was estimated to be 20% of the whole liver volume by preoperative MRI volumetry, was macroscopically observed to be fibrotic. Intra-surgical frozen section analysis revealed early periportal fibrosis and middle-grade micro- and macrovesicular steatosis of the liver tissue (20% of hepatocytes). Based on these intra-operative results, the decision was made not to proceed with the planned hemihepatectomy. Tumour biopsies revealed a cavernous haemangioma. The histology of the explanted liver confirmed low-grade periportal fibrosis and low-grade micro- and macrovesicular steatosis.

Because of the aggravation of symptoms and the non-resectability of the haemangioma, the patient was listed for liver transplantation in January 2013.The initial model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score[15] was 8 points. However, in contrast to normal or only mildly deviated laboratory parameters, the clinical condition of the patient continuously worsened in the following months. The patient developed progressive ascites from portal hypertension due to thrombosis of the right portal vein branch and tumour-compression of the left portal vein branch as well as compression of the infra-hepatic vena cava and hepatic veins. Massive ascites led to reduced mobility and shortness of breath; the patient’s walking distance was declared to be less than 100 m. Furthermore, the patient suffered from high-grade malnutrition. Draining of a total of 19 L of ascites in March 2013 only temporarily improved the patient’s symptoms. In April 2013, the patient developed thromboembolisms in both lower lobe pulmonary arteries.

Based on the low MELD score, ranging from 7 to 10 points and the progressive clinical deterioration, non-standard exception status was requested from the organ allocation organization (Eurotransplant, Leiden, Netherlands). The rationale for the application for non-standard exception status was the similarity of this patient’s presentation to that of adult polycystic liver disease. The request was approved, and an initial match MELD of 22 was assigned in June 2013.

In the following six months, the clinical condition of the patient further deteriorated. A repeat ascites puncture was necessary in September 2013. Hyponatremia developed, with the lowest serum sodium concentration being 128 mmol/L in October 2013. At a match MELD score of 28 points, an appropriate donor-organ was offered and was transplanted in the beginning of February 2014.

The patient was transferred from the post-operative ICU to the transplant ward on post-operative day 6 and was discharged home on post-operative day 17 after an uneventful post-transplantation course. On outpatient follow-up, the patient presented well, with normal liver function tests and no ascites, and she had begun to resume a normal level of every day activity.

According to the SF30-Health Survey[16], the life quality of our patient rose after transplantation in both tested categories. From before to seven weeks after transplantation, the physical score increased from 15.3 to 40.5 points, and the mental score increased from 5.9 to 64.3 points (Figures 1 and 2).

Giant haemangiomas of the liver are often asymptomatic but can cause serious problems. Displacement of organs and structures, thrombosis, bleeding and consumption coagulopathy can occur. Addition symptoms include ascites, respiratory distress, pain, obstructive jaundice, biliary colic and gastric outlet obstruction[17]. When the tumour exceeds a certain volume as in this case, often surgical treatment is inevitable. The optimal surgical management is controversial, with the options being resection, enucleation and liver transplantation[18-21].

Despite its complexity, liver transplantation should be considered for non-resectable benign hepatic neoplasms in patients with imminent life-threatening complications, an increased risk of malignant transformation, an underlying liver disease or the presence of symptoms causing severe discomfort[1,22]. Apart from the above-mentioned cases of HL, the reported data shows that the most common indications for liver transplantation are polycystic liver disease, hepatocellular adenoma or adenomatosis and focal nodular hyperplasia[22-28].

Our patient was considered a candidate for OLT because of the following main factors: (1) Functionally non-resectable haemangioma due to steatosis of the remnant liver, presumably caused by disturbed blood perfusion due to tumour compression; and (2) progressive clinical deterioration with refractory ascites, cachexia, thromboembolism and respiratory distress caused by portal hypertension and inferior vena cava compression. However, the patient’s poor clinical condition with a greatly reduced quality of life was under-represented by her low labMELD score because the laboratory parameters were only mildly affected.

At our centre, the patient presented with a worsening clinical condition but had low probability of receiving an organ transplant in the context of the labMELD scoring system. This led us to request non-standard exception status. We justified the request based on the comparability of the patient’s symptoms with those characteristic of polycystic liver disease, such as ascites, malnutrition, and venous outflow obstruction due to compression. In Germany, polycystic liver disease qualifies for standard exception status. Our petition was reviewed and accepted by the Audit group after two months of review. If non-standard exception status is approved, the patient receives an initial match MELD score that corresponds to a 3-mo-lethality of 15%, with an increase in lethality of 10% every 3 mo. Rodriguez-Luna et al[29] found that recurrent ascites is the most common reason for submitting a non-standard exception appeal. They noticed a regional variety in the quantity of non-standard exception requests and call for the publication of guidelines to overcome regional inequalities.

Moreover, it has been observed that ascites and hyponatremia in cirrhotic patients with relatively preserved liver and renal functions leads to a significant increase in the risk of mortality, which is generally underestimated by the labMELD scoring system. A previous study showed that hyponatremia (serum sodium concentration under 130 μg/L) was associated with an estimated 2.65-fold increase in the instantaneous risk of mortality[30]. Other studies indicate that the risk of mortality in the presence of moderate ascites corresponds with a labMELD score of 4.46-4.70 points greater than that determined using the current labMELD scoring system; this generates concern for patients with a low MELD score (under 21 points)[31,32]. Therefore, several authors have proposed an extension of MELD with indicators for hemodynamic decompensation, such as serum sodium concentration and, especially, ascites, to counteract this disadvantage of the current scoring system[31,33-37]. Our patient with severe ascites and a low serum sodium concentration (≤ 130 μg/L over 4 mo) would have benefited from an extension of the listing criteria. Because institutional recalculation of priority in organ allocation is pending, our request for non-standard exception status considerably improved the chances for transplantation and survival for this patient. In the current clinical context, a request for non-standard exception status should be taken into consideration early in the clinical course of cases similar to one presented here.

A 46-year-old female presented with a giant liver mass, continuous increase in abdominal girth and a feeling of fullness over the past three years.

Massive ascites and malnutrition.

Malignant tumours (hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma), benign neoplasms (hepatocellular adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia and abscesses).

The levels of liver enzymes, serum creatinine, and tumour markers for hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer were within their normal ranges. Cholestasis parameters were slightly elevated (alkaline phosphatase: 2.06 μmol/L; γ-glutamyltransferase: 1.70 μmol/L). Later, hyponatremia developed, with the lowest serum sodium concentration being 128 mmol/L.

A computed tomography scan showed a mass with peripheral nodular enhancements in the arterial phase with progressive centripetal filling toward the centre in the portal venous and delayed phases and central necrosis. Size of the tumour: 21.7 cm × 23.7 cm × 25.5 cm, located in segments V-VIII.

Tumour biopsies showed a cavernous haemangioma. The histology of the explanted liver showed low-grade periportal fibrosis and low-grade micro- and macrovesicular steatosis.

Non-resectable mass; therefore, the treatment plan was orthotopic liver transplantation.

Very few cases of orthotopic liver transplantation because of the mass effects of a haemangioma have been reported in the literature.

Liver haemangioma is a benign mass that occurs in the liver. It is composed of a tangle of blood vessels. Haemangiomas of the liver with a diameter over 4 cm are called giant haemangiomas.

Liver transplantation should be considered early in patients with non-resectable, symptomatic benign liver tumours. Application for non-standard exception status could allow for transplantation in patients with severe clinical conditions but low lab model for end-stage liver disease (labMELD) scores and should be done early in the course of the disease.

This manuscript delivers a strong message regarding unusual candidates for liver transplantation and makes strong suggestions revisions to the current labMELD allocation system. This case report indicates that both careful research and review of the existing literature in this field and in depth consideration of the ethical motives and procedures behind the non-standard exception status application rules are warranted.

| 1. | Chiche L, Adam JP. Diagnosis and management of benign liver tumors. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33:236-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yoon SS, Charny CK, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, Schwartz LH, Blumgart LH, DeMatteo RP. Diagnosis, management, and outcomes of 115 patients with hepatic hemangioma. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:392-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Erdogan D, Busch OR, van Delden OM, Bennink RJ, ten Kate FJ, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Management of liver hemangiomas according to size and symptoms. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1953-1958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gandolfi L, Leo P, Solmi L, Vitelli E, Verros G, Colecchia A. Natural history of hepatic haemangiomas: clinical and ultrasound study. Gut. 1991;32:677-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Choi BY, Nguyen MH. The diagnosis and management of benign hepatic tumors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:401-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schnelldorfer T, Ware AL, Smoot R, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Nagorney DM. Management of giant hemangioma of the liver: resection versus observation. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:724-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bozkaya H, Cinar C, Besir FH, Parıldar M, Oran I. Minimally invasive treatment of giant haemangiomas of the liver: embolisation with bleomycin. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vagefi PA, Klein I, Gelb B, Hameed B, Moff SL, Simko JP, Fix OK, Eilers H, Feiner JR, Ascher NL. Emergent orthotopic liver transplantation for hemorrhage from a giant cavernous hepatic hemangioma: case report and review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Klompmaker IJ, Sloof MJ, van der Meer J, de Jong GM, de Bruijn KM, Bams JL. Orthotopic liver transplantation in a patient with a giant cavernous hemangioma of the liver and Kasabach-Merritt syndrome. Transplantation. 1989;48:149-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Longeville JH, de la Hall P, Dolan P, Holt AW, Lillie PE, Williams JA, Padbury RT. Treatment of a giant haemangioma of the liver with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome by orthotopic liver transplant a case report. HPB Surg. 1997;10:159-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ferraz AA, Sette MJ, Maia M, Lopes EP, Godoy MM, Petribú AT, Meira M, Borges Oda R. Liver transplant for the treatment of giant hepatic hemangioma. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1436-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Meguro M, Soejima Y, Taketomi A, Ikegami T, Yamashita Y, Harada N, Itoh S, Hirata K, Maehara Y. Living donor liver transplantation in a patient with giant hepatic hemangioma complicated by Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: report of a case. Surg Today. 2008;38:463-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kumashiro Y, Kasahara M, Nomoto K, Kawai M, Sasaki K, Kiuchi T, Tanaka K. Living donor liver transplantation for giant hepatic hemangioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome with a posterior segment graft. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:721-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yildiz S, Kantarci M, Kizrak Y. Cadaveric liver transplantation for a giant mass. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:e10-e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, D’Amico G, Dickson ER, Kim WR. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3462] [Cited by in RCA: 3775] [Article Influence: 151.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Ware JE, Gandek B, Kosinski M, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Brazier J, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplège A, Prieto L. The equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country-specific algorithms in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1167-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jr MA, Papaiordanou F, Gonçalves JM, Chaib E. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic hemangiomas: A review of the literature. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:428-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Brouwers MA, Peeters PM, de Jong KP, Haagsma EB, Klompmaker IJ, Bijleveld CM, Zwaveling JH, Slooff MJ. Surgical treatment of giant haemangioma of the liver. Br J Surg. 1997;84:314-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Hoekstra LT, Bieze M, Erdogan D, Roelofs JJ, Beuers UH, van Gulik TM. Management of giant liver hemangiomas: an update. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7:263-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hochwald SN, Blumgart LH. Giant hepatic hemangioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrom: is the appropriate treatment enucleation or transplantation? HPB Surg. 2000;11:413-419. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ho HY, Wu TH, Yu MC, Lee WC, Chao TC, Chen MF. Surgical management of giant hepatic hemangiomas: complications and review of the literature. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:70-78. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Pinna AD. Liver transplantation for benign hepatic tumors: a systematic review. Dig Surg. 2010;27:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tepetes K, Selby R, Webb M, Madariaga JR, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Orthotopic liver transplantation for benign hepatic neoplasms. Arch Surg. 1995;130:153-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Marino IR, Scantlebury VP, Bronsther O, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Total hepatectomy and liver transplant for hepatocellular adenomatosis and focal nodular hyperplasia. Transpl Int. 1992;5 Suppl 1:S201-S205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Vagefi PA, Eilers H, Hiniker A, Freise CE. Liver transplantation for giant hepatic angiomyolipoma. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:985-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Di Sandro S, Slim AO, Lauterio A, Giacomoni A, Mangoni I, Aseni P, Pirotta V, Aldumour A, Mihaylov P, De Carlis L. Liver adenomatosis: a rare indication for living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:1375-1377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lerut J, Ciccarelli O, Rutgers M, Orlando G, Mathijs J, Danse E, Goffin E, Gigot JF, Goffette P. Liver transplantation with preservation of the inferior vena cava in case of symptomatic adult polycystic disease. Transpl Int. 2005;18:513-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fujita S, Mekeel KL, Fujikawa T, Kim RD, Foley DP, Hemming AW, Howard RJ, Reed AI, Dixon LR. Liver-occupying focal nodular hyperplasia and adenomatosis associated with intrahepatic portal vein agenesis requiring orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2006;81:490-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rodriguez-Luna H, Vargas HE, Moss A, Reddy KS, Freeman RB, Mulligan D. Regional variations in peer reviewed liver allocation under the MELD system. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2244-2247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ruf AE, Kremers WK, Chavez LL, Descalzi VI, Podesta LG, Villamil FG. Addition of serum sodium into the MELD score predicts waiting list mortality better than MELD alone. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:336-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Heuman DM, Abou-Assi SG, Habib A, Williams LM, Stravitz RT, Sanyal AJ, Fisher RA, Mihas AA. Persistent ascites and low serum sodium identify patients with cirrhosis and low MELD scores who are at high risk for early death. Hepatology. 2004;40:802-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Somsouk M, Kornfield R, Vittinghoff E, Inadomi JM, Biggins SW. Moderate ascites identifies patients with low model for end-stage liver disease scores awaiting liver transplantation who have a high mortality risk. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:129-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kim WR, Biggins SW, Kremers WK, Wiesner RH, Kamath PS, Benson JT, Edwards E, Therneau TM. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1018-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 935] [Cited by in RCA: 1102] [Article Influence: 61.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Somsouk M, Guy J, Biggins SW, Vittinghoff E, Kohn MA, Inadomi JM. Ascites improves upon [corrected] serum sodium plus [corrected] model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) for predicting mortality in patients with advanced liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:741-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Fisher RA, Heuman DM, Harper AM, Behnke MK, Smith AD, Russo MW, Zacks S, McGillicuddy JW, Eason J, Porayko MK. Region 11 MELD Na exception prospective study. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:62-67. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Leise MD, Yun BC, Larson JJ, Benson JT, Yang JD, Therneau TM, Rosen CB, Heimbach JK, Biggins SW, Kim WR. Effect of the pretransplant serum sodium concentration on outcomes following liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:687-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Biggins SW, Kim WR, Terrault NA, Saab S, Balan V, Schiano T, Benson J, Therneau T, Kremers W, Wiesner R. Evidence-based incorporation of serum sodium concentration into MELD. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1652-1660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 572] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Marino IR, Maurizio S, Ramsay M

S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D