Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.103656

Revised: July 6, 2025

Accepted: October 11, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 414 Days and 7.9 Hours

Post-transplant tertiary hyperparathyroidism (PT-tHPT) is a well-recognized complication following kidney transplantation, characterized by persistent ex

To evaluate the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of PT-tHPT amongst kidney transplant recipients.

A total of 887 transplant recipients who underwent transplantation between 2000 and 2020 were evaluated. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression was performed to determine the predictors of tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Graft and recipient outcomes were assessed using multivariable Cox regression. A separate multivariable Cox regression was performed to determine the effect of treatment strategies on outcomes.

PT-tHPT, defined as elevated PTH (> 65 ng/L) and persistent hypercalcemia (> 2.60 mmol/L), was diagnosed in 14% of recipients. Risk factors for PT-tHPT included older age [odds ratio (OR) = 1.36, P < 0.001], Asian ethnicity (OR = 0.33, P = 0.006), total ischemia time (OR = 1.03, P = 0.048 per hour), pre-transplant serum calcium (OR = 1.38, P < 0.001) per decile increase, pre-transplant PTH level (OR = 1.31, P < 0.001) per decile increase, longer dialysis duration (OR = 1.12, P = 0.002) per year, history of acute rejection (OR = 2.37, P = 0.012), and slope of estimated glomerular filtration rate change (OR = 0.91, P = 0.001). There were a 3.4-fold higher risk of death-censored graft loss and a 1.9-fold greater risk of recipient death with PT-tHPT. The three treatment strategies of conservative management, calcimimetic and parathyroidectomy did not significantly change the graft or patient outcome.

Pretransplant elevated calcium and PTH levels, older age and dialysis duration are associated with PT-tHPT. While PT-tHPT significantly affects graft and recipient survival, the treatment strategies did not affect survival.

Core Tip: This study explores post-transplant tertiary hyperparathyroidism (PT-tHPT) in kidney transplant recipients, identifying elevated pre-transplant calcium and parathyroid hormone levels, prolonged dialysis duration, and acute rejection as key risk factors. PT-tHPT significantly increases the risks of graft loss and patient mortality. However, survival outcomes were comparable across treatment strategies: (1) Conservative management; (2) Calcimimetics; and (3) Parathyroidectomy. These findings highlight the need for optimized pre-transplant care and vigilant post-transplant monitoring to reduce PT-tHPT-related complications. Further research is essential to determine the most effective treatment strategy to improve outcomes and minimize morbidity and mortality associated with PT-tHPT.

- Citation: Hanson S, Menendez Lorenzo J, Chukwu CA, Rao A, Middleton R, Kalra PA. Incidence, risk factors and survival outcomes of post-transplant tertiary hyperparathyroidism in kidney recipients. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 103656

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/103656.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.103656

Post-transplant tertiary hyperparathyroidism (PT-tHPT) is a common complication following kidney transplantation, affecting metabolic parameters and accompanied by morbidity[1]. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism (tHPT) occurs when there is an excessive secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH) by the parathyroid glands. This is usually associated with hypercalcemia. The tHPT typically develops after prolonged secondary hyperparathyroidism (sHPT). It is commonly seen in patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD)[2]. The condition occurs when the over-stimulated parathyroid glands, caused by chronic kidney disease (CKD)-related sHPT, can no longer switch off hormone production once serum calcium concentration has normalized. As a result, they continue to produce large amounts of PTH.

Before transplantation, up to 75% of patients with CKD develop sHPT, with prevalence ranging from 32% in CKD stage 3 to 93% ESKD[3,4]. The sHPT arises due to impaired phosphate homeostasis in CKD, leading to overproduction of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) and reduced levels of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D [1,25(OH)2D]. Consequently, serum calcium and PTH levels become dysregulated[5,6].

The decline in 1,25(OH)2D, combined with elevated phosphate levels, reduces intestinal calcium absorption and stimulates excessive PTH secretion. Prolonged stimulation of the parathyroid glands promotes cellular growth, resulting in diffuse or nodular hyperplasia. Nodular hyperplasia, in particular, reduces sensitivity to calcium and vitamin D feed

The sHPT is associated with poor outcomes in CKD. Patients with sHPT have twice the risk of major adverse cardiac events and a fivefold higher risk of CKD progression[7]. Additionally, CKD patients with sHPT are four times more likely to initiate dialysis or die compared to those without sHPT[8].

Following kidney transplantation, most patients experience normalization of PTH levels. However, approximately 25% fail to do so and develop PT-tHPT[9,10]. This condition is characterized by persistently elevated PTH and calcium levels, alongside reduced phosphate levels, despite successful transplantation. Variations in diagnostic thresholds have con

PT-tHPT has been linked to adverse outcomes, including an increased risk of renal graft dysfunction and graft failure[12]. However, optimal management remains uncertain. Treatment options range from conservative strategies such as dietary modifications and immunosuppression adjustments to pharmacological interventions like calcimimetics and surgical parathyroidectomy. The lack of robust evidence complicates treatment decisions, and standardized guidelines are lacking.

Given its potential impact on graft function and recipient survival, further investigation is essential.

To identify risk factors associated with PT-tHPT, evaluate the impact of PT-tHPT on allograft and patient survival, and to assess the effects of different treatment strategies on survival outcomes.

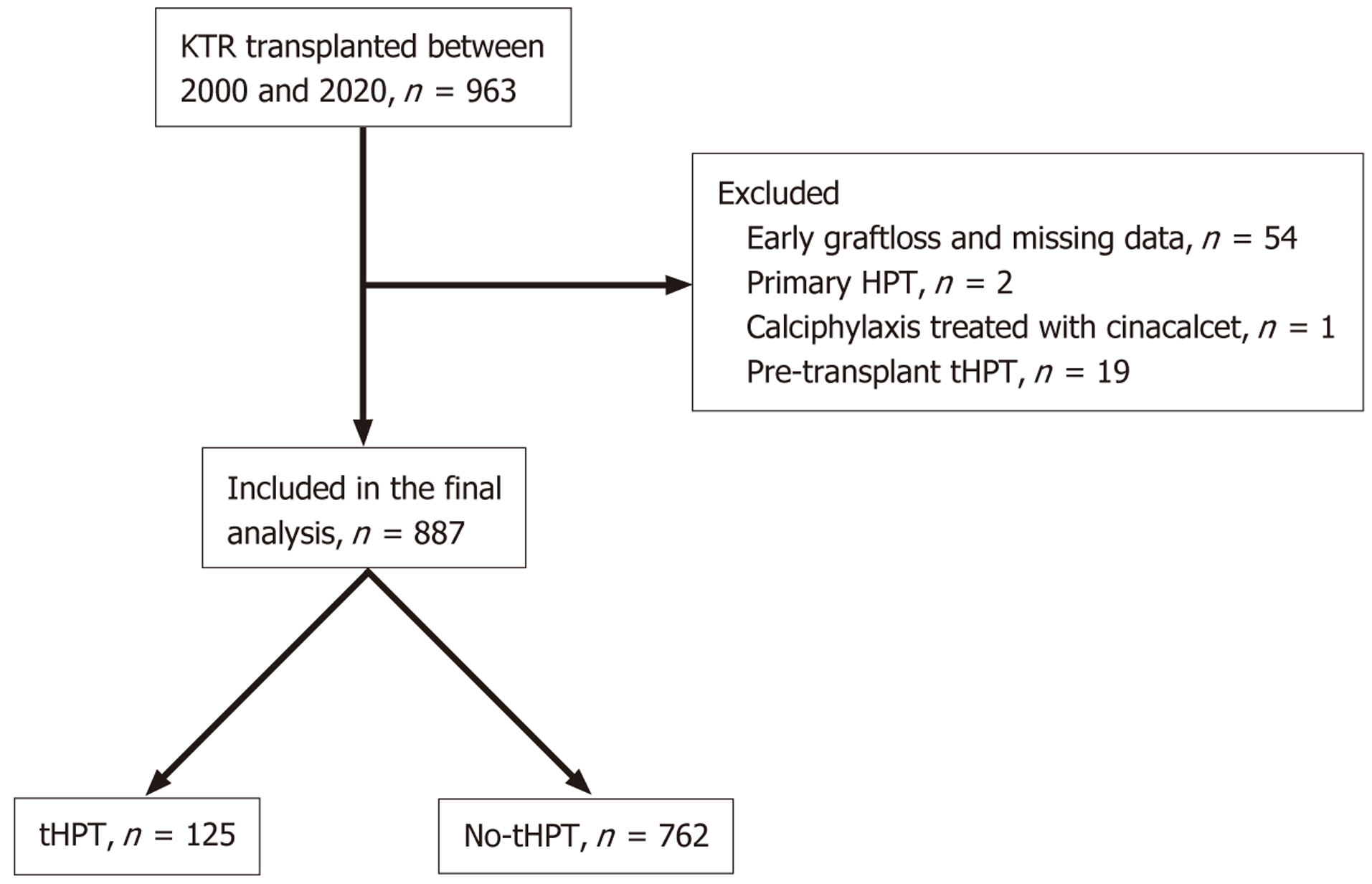

This retrospective cohort study focused on kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) who underwent transplantation from January 2000 to December 2020. The cohort was identified from a comprehensive database of KTRs regularly followed up at a single tertiary nephrology centre. Exclusion criteria included patients experiencing graft loss within the first three months post-transplantation, individuals with a prior diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism (HPT), a history of parathyroidectomy before transplantation, or those receiving calcimimetic treatment for indications other than HPT (such as calcific uremic arteriolopathy). A flow chart of subject selection is depicted in Figure 1.

The explanatory variables included age at transplantation, gender, ethnicity, body mass index, primary kidney disease, dialysis vintage, history of pre-transplant diabetes, allograft type received, degree of human leucocyte antigen mismatch, immunosuppressive regimen, and smoking history. Pre-transplant bone profile parameters were also recorded. These were measured as the median of all the test results over the pre-transplant period and divided into deciles of increments. They included serum calcium (mmol/L), phosphate (mmol/L), and PTH (ng/L). Additionally, the immunosuppression regime, history of biopsy-proven acute rejection, history of opportunistic (DNA) viral infections and smoking history were also recorded. The baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), defined as eGFR at 3 months post-tran

There is no consensus on a PTH level that clearly defines the presence of persistent post-transplant HPT. In our study, PTH levels above the upper limit of normal (65 pg/mL or 6.9 pmol/L) were considered elevated[13].

PT-tHPT was defined as elevated PTH along with persistent hypercalcemia (serum adjusted calcium > 2.6 mmol/L) for at least 6 months post-transplantation, accompanied by low or normal phosphate levels[13]. Graft survival was evaluated as death-censored graft survival, measuring the time until kidney transplant failure leading to dialysis or re-transp

All recipients in the study received maintenance immunosuppression, which comprised a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) based regimen utilizing either tacrolimus or cyclosporin. An anti-proliferative agent, specifically mycophenolic acid or azathioprine was also administered for individuals without contraindications. The administration of corticosteroids was tailored based on the immunologic risk status of the recipients. Those with a standard immunologic risk profile received a brief course of corticosteroids lasting 1-2 weeks at transplantation. In contrast, recipients deemed to be at high immunologic risk, characterized by factors such as younger recipients or older donors, a calculated panel reactive anti

Treatment strategies for PT-tHPT were categorized into conservative management, calcimimetic therapy (using calci

Data was extracted from electronic patient records, and collection was continued until clinical endpoints were reached, including allograft failure, recipient death, recipient loss to follow-up, or the end of the study period in December 2021.

Continuous variables with a normal distribution were presented as mean (SD), while continuous variables with non-normal distributions were described using the median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons were conducted using two-tailed t-tests for parametric variables and Wilcoxon's sign-rank test for non-parametric variables. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test.

The rate of eGFR change was expressed as a continuous variable (slope over time), for each patient, was determined by employing a linear mixed-effects regression model. This model was constructed based on the yearly eGFR values for each patient, utilizing the final eGFR value for each year following transplantation. This approach allowed for the calculation of the slope of eGFR change, where higher values reflect slower decline or improving graft function, providing a quan

The independent risk factors for PT-tHPT were determined using multivariable binary logistic regression. The mul

Multicollinearity diagnostics were performed using generalized variance inflation factors (GVIF). All predictors in the multivariable model demonstrated low collinearity, with adjusted-GVIF values close to 1.0, suggesting no significant inflation of variance due to correlated predictors (Supplementary Table 1).

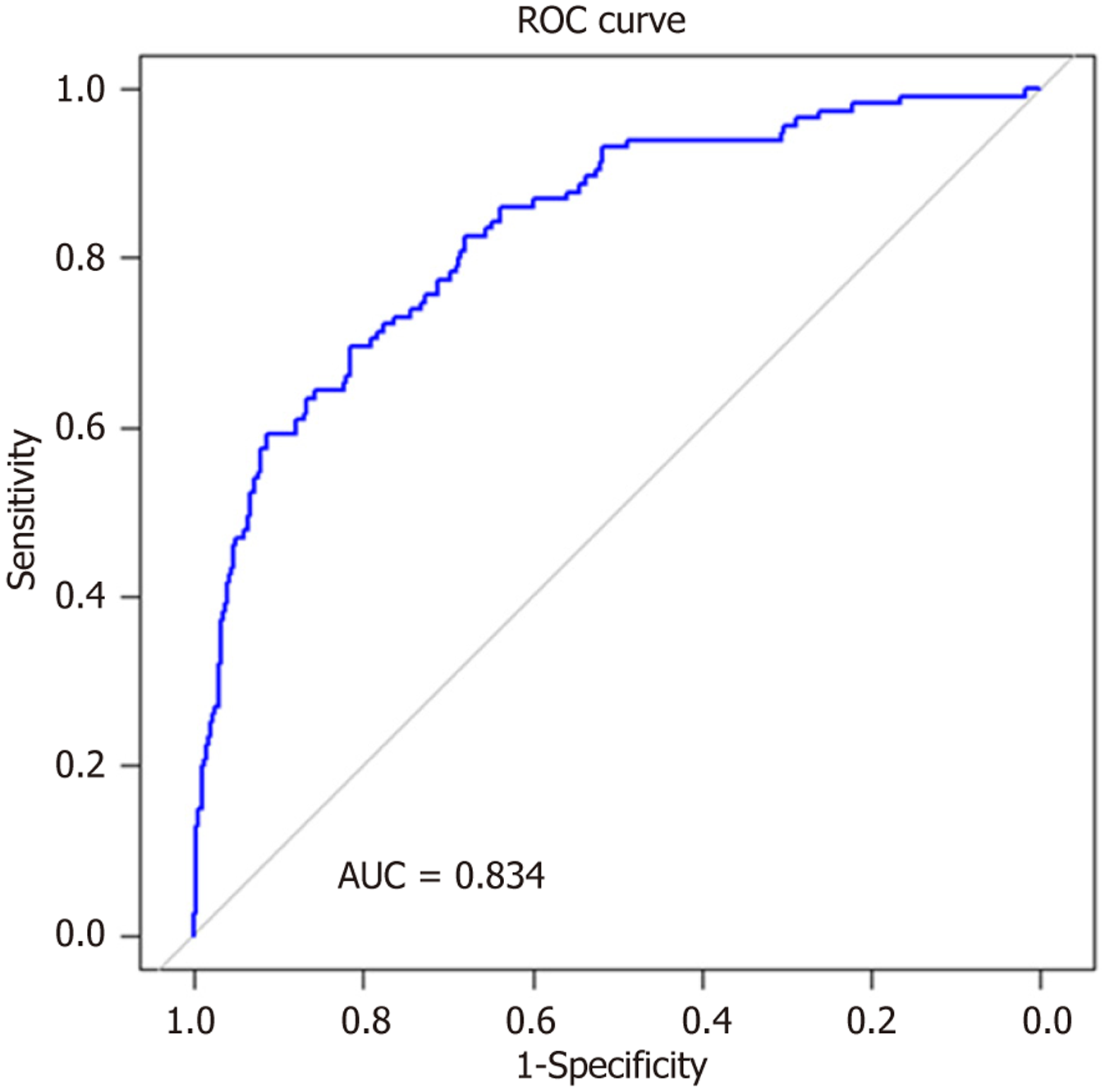

The performance of the logistic regression model was also evaluated using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. The ROC curve was generated by varying the classification threshold, and the true positive rate (sensitivity) and false positive rate (1-specificity) were calculated at multiple threshold values. The area under the curve (AUC) was com

The impact of PT-tHPT on graft and recipient survival was determined. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to illustrate the unadjusted survival of patients and grafts, and comparisons were made using the log-rank test. Mul

A sensitivity analysis was conducted after excluding recipients who developed tHPT after three years of trans

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.3.0) with the utilization of various R packages, including the “arsenal”, "survival", “pROC”, and “glm” packages.

Amongst 963 subjects in the initial study cohort, 76 subjects were excluded after applying the exclusion criteria leaving 887 subjects in the final analysis. Table 1 presents an overview of the cohort characteristics. The mean age at tran

| Characteristics | PT-tHPT (n = 125) | Non-tHPT (n = 762) | Total (n = 887) | P value |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 50.5 (13.2) | 47.0 (15.5) | 47.5 (15.2) | 0.016 |

| Sex | 0.617 | |||

| Male | 74 (59.2) | 469 (61.5) | 543 (61.2) | |

| Female | 51 (40.8) | 293 (38.5) | 344 (38.8) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.028 | |||

| White | 110 (88.0) | 609 (79.9) | 719 (81.1) | |

| Asian | 11 (8.8) | 125 (16.4) | 136 (15.3) | |

| Black | 4 (3.2) | 12 (1.6) | 16 (1.8) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.1) | 16 (1.8) | |

| Pretransplant body mass index, mean (SD) | 27.4 (5.0) | 27.0 (8.3) | 27.1 (7.9) | 0.634 |

| Donor characteristics | ||||

| Donor type category | 0.006 | |||

| Deceased donor | 101 (80.8) | 523 (68.7) | 624 (70.4) | |

| Living donor | 24 (19.2) | 238 (31.3) | 262 (29.6) | |

| Total human leucocyte antigen mismatch, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0-3.0) | 3.0 (2.0-3.0) | 3.0 (2.0-3.0) | 0.425 |

| Total ischaemia time, mean (SD) | 14.1 (7.1) | 12.5 (7.7) | 12.7 (7.6) | 0.037 |

| Recipients’ characteristics | ||||

| Primary renal disease | 0.033 | |||

| Adult polycystic kidney disease | 12 (9.6) | 104 (13.6) | 116 (13.1) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 32 (25.6) | 207 (27.2) | 239 (26.9) | |

| Diabetic kidney disease | 9 (7.2) | 99 (13.0) | 108 (12.2) | |

| Hypertensive kidney disease | 8 (6.4) | 52 (6.8) | 60 (6.8) | |

| Reflux/chronic pyelonephritis | 28 (22.4) | 90 (11.8) | 118 (13.3) | |

| Unknown | 21 (16.8) | 130 (17.1) | 151 (17.0) | |

| Other | 15 (12.0) | 80 (10.5) | 95 (10.7) | |

| Dialysis vintage (pre-emptive transplants excluded), median (IQR) | 39.0 (20.0-63.0) | 23.0 (11.0-38.0) | 25.0 (12.0-44.0) | < 0.001 |

| Pretransplant diabetes | 20 (16.0) | 136 (17.8) | 156 (17.6) | 0.615 |

| Transplant number, mean (SD) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.4) | 0.013 |

| Pre-emptive transplant | 24 (19.8) | 246 (34.2) | 270 (32.1) | 0.002 |

| Pre-transplant calcium (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 2.5 (2.4-2.5) | 2.3 (2.2-2.4) | 2.3 (2.2-2.4) | < 0.001 |

| Pre-transplant phosphate (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) | 1.6 (1.3-1.9) | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) | 0.153 |

| Pre-transplant PTH (ng/L), median (IQR) | 415.8 (232.0-717.9) | 185.0 (97.8-307.8) | 202.0 (107.0-360.0) | < 0.001 |

| Post-transplant PTH (ng/L), median (IQR) | 135.8 (107.6-240.1) | 83.7 (58.3-119.9) | 88.4 (61.7-138.1) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking history | 0.073 | |||

| Non-smoker | 110 (92.4) | 604 (86.5) | 714 (87.4) | |

| Current smoker | 9 (7.6) | 94 (13.5) | 103 (12.6) | |

| Immunosuppression regime | ||||

| Main immunosuppression | 0.557 | |||

| Tacrolimus | 110 (88.7) | 674 (90.1) | 784 (89.9) | |

| Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor | 3 (2.4) | 9 (1.2) | 12 (1.4) | |

| Cyclosporin | 11 (8.9) | 65 (8.7) | 76 (8.7) | |

| Antimetabolite | 0.739 | |||

| None | 14 (11.3) | 80 (10.7) | 94 (10.8) | |

| Mycophenolic acid | 97 (78.2) | 571 (76.3) | 668 (76.6) | |

| Azathioprine | 13 (10.5) | 97 (13.0) | 110 (12.6) | |

| Steroid regime | 0.016 | |||

| < 6 monhs of glucocorticoid | 54 (45.4) | 405 (57.2) | 459 (55.5) | |

| > 6 months of glucocorticoid | 65 (54.6) | 303 (42.8) | 368 (44.5) | |

| Other | ||||

| Baseline eGFR (mL/minute/1.73 m2), median (IQR) | 50.0 (37.2-62.2) | 51.0 (40.8-65.0) | 51.0 (40.0-64.0) | 0.373 |

| History of acute rejection | 20 (16.5) | 78 (10.9) | 98 (11.7) | 0.074 |

| The eGFR slope (mL/minute/year), median (IQR) | 1.4 (3.20.0) | 0.8 (2.70.5) | 0.9 (2.70.5) | 0.027 |

One-third of recipients (32%) underwent pre-emptive transplantation. Among those who did not receive pre-emptive transplantation, median duration receiving dialysis was 25 months (IQR: 12.0-44.0 months). Two-thirds of the cohort (68%) received deceased donor allografts. Most recipients received a tacrolimus-based immunosuppression regimen (90%), with 45% of subjects receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy. The median pre-transplant PTH was 202 ng/L (IQR: 107-360 ng/L) [21.4 pmol/L (IQR: 11.3-38.2 pmol/L)].

Over a median follow-up period of 7.3 years (IQR: 4-12 years), 125 subjects (14%) developed PT-tHPT. Table 2 shows the result of the univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis.

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable model | |||||

| n | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (per decade) | 887 | 1.17 | 1.03-1.33 | 0.016 | 1.36 | 1.15-1.62 | < 0.001 |

| Gender: Female | 887 | 1.10 | 0.75-1.62 | 0.62 | |||

| Ethnicity | 871 | 0.033 | - | - | - | ||

| White | 1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Asian1 | 0.49 | 0.24-0.89 | 0.33 | 0.14- 0.70 | 0.006 | ||

| Black | 1.85 | 0.51-5.41 | 0.79 | 0.16-3.02 | 0.75 | ||

| Other | 0.00 | 0.00-0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00-0.00 | 0.98 | ||

| Pretransplant body mass index | 887 | 1.00 | 0.98-1.03 | 0.71 | - | - | - |

| Primary renal disease | 887 | 0.044 | - | - | - | ||

| Adult polycystic kidney disease | 1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Glomerulonephritis | 1.34 | 0.68-2.81 | - | - | - | ||

| Diabetic kidney disease | 0.79 | 0.31-1.94 | - | - | - | ||

| Hypertensive kidney disease | 1.33 | 0.50-3.43 | - | - | - | ||

| Reflux/chronic pyelonephritis | 2.70 | 1.32-5.79 | - | - | - | ||

| Unknown | 1.40 | 0.67-3.06 | - | - | - | ||

| Other | 1.63 | 0.72-3.73 | - | - | - | ||

| Pre-emptive transplant | 887 | 0.50 | 0.31-0.78 | 0.002 | |||

| Pretransplant diabetes | 887 | 0.88 | 0.51-1.44 | 0.61 | - | - | - |

| Donor type: Living donor | 887 | 0.52 | 0.32-0.82 | 0.004 | - | - | - |

| Total human leukocyte antigen mismatch | 887 | 1.05 | 0.92-1.20 | 0.44 | - | - | - |

| Immunosuppression | 887 | 0.75 | - | - | - | ||

| Tacrolimus | 1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor | 1.68 | 0.37-5.47 | - | - | - | ||

| Cyclosporin | 0.98 | 0.48-1.84 | - | - | - | ||

| Antimetabolite | 887 | 0.68 | - | - | - | ||

| None | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Mycophenolic acid | 0.96 | 0.54-1.83 | - | - | - | ||

| Azathioprine | 0.74 | 0.33-1.68 | - | - | - | ||

| Corticosteroid regime | 887 | 0.023 | - | - | - | ||

| < 6 months of glucocorticoid | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| > 6 months glucocorticoid | 1.55 | 1.06-2.28 | - | - | - | ||

| Total ischaemia time | 887 | 1.03 | 1.00-1.05 | 0.038 | 1.03 | 1.00-1.07 | 0.048 |

| Dialysis vintage | 887 | 1.19 | 1.12-1.26 | < 0.001 | 1.12 | 1.04-1.20 | 0.002 |

| Baseline eGFR (per 10 mL/minute increase) | 887 | 0.98 | 0.90-1.05 | 0.66 | - | - | - |

| History of acute rejection | 838 | 1.62 | 0.93-2.72 | 0.086 | 2.37 | 1.19-4.60 | 0.012 |

| The eGFR slope | 887 | 0.93 | 0.89-0.97 | 0.001 | 0.91 | 0.87-0.96 | 0.001 |

| Median pretransplant calcium (per decile increase) | 887 | 1.35 | 1.25-1.46 | < 0.001 | 1.38 | 1.26-1.51 | < 0.001 |

| Median pretransplant phosphate (per decile increase) | 887 | 1.05 | 0.99-1.12 | 0.13 | - | - | - |

| Median pretransplant parathyroid hormone (per decile increase) | 887 | 1.26 | 1.17-1.36 | < 0.001 | 1.31 | 1.20-1.43 | < 0.001 |

| Posttransplant diabetes | 831 | 1.50 | 0.91-2.39 | 0.11 | - | - | - |

| Smoking history | 816 | 0.077 | 0.070 | ||||

| None-smoker | - | - | - | - | |||

| Current smoker | 0.53 | 0.24-1.02 | 0.48 | 0.20-1.02 | |||

The univariate logistic regression analysis identified several factors associated with posttransplant PT-tHPT. These include age at transplantation, ethnicity (Asian ethnicity), primary renal disease, longer duration of dialysis (per year), preemptive transplantation, longer total ischemia time (per hour), longer duration of glucocorticoid therapy (greater than 6 months), higher pretransplant calcium and PTH levels and higher rate of eGFR decline (per year).

In the multivariable regression model, the factors associated with increased risk of PT-tHPT were older age at transplantation [odds ratio (OR) = 1.36, P < 0.001], prolonged total ischemia time (per hour increase) (OR = 1.03, P = 0.48), dialysis vintage (per year) (OR = 1.12, P = 0.002), history of acute rejection (OR = 2.37, P = 0.012), pretransplant median serum calcium (OR = 1.38, P < 0.001) per decile increase, and pretransplant PTH levels (OR = 1.31, P < 0.001) per decile increase. Conversely, a positive eGFR slope (the rate of eGFR change over time) (OR = 0.91, P = 0.001) and Asian ethnicity (OR = 0.33, P = 0.006) were associated with lower odds of PT-tHPT per unit eGFR change was associated with lower odds of PT-tHPT. The AUC for our model is 0.83 (Figure 2), indicating strong discrimination between individuals who developed PT-tHPT and those who did not.

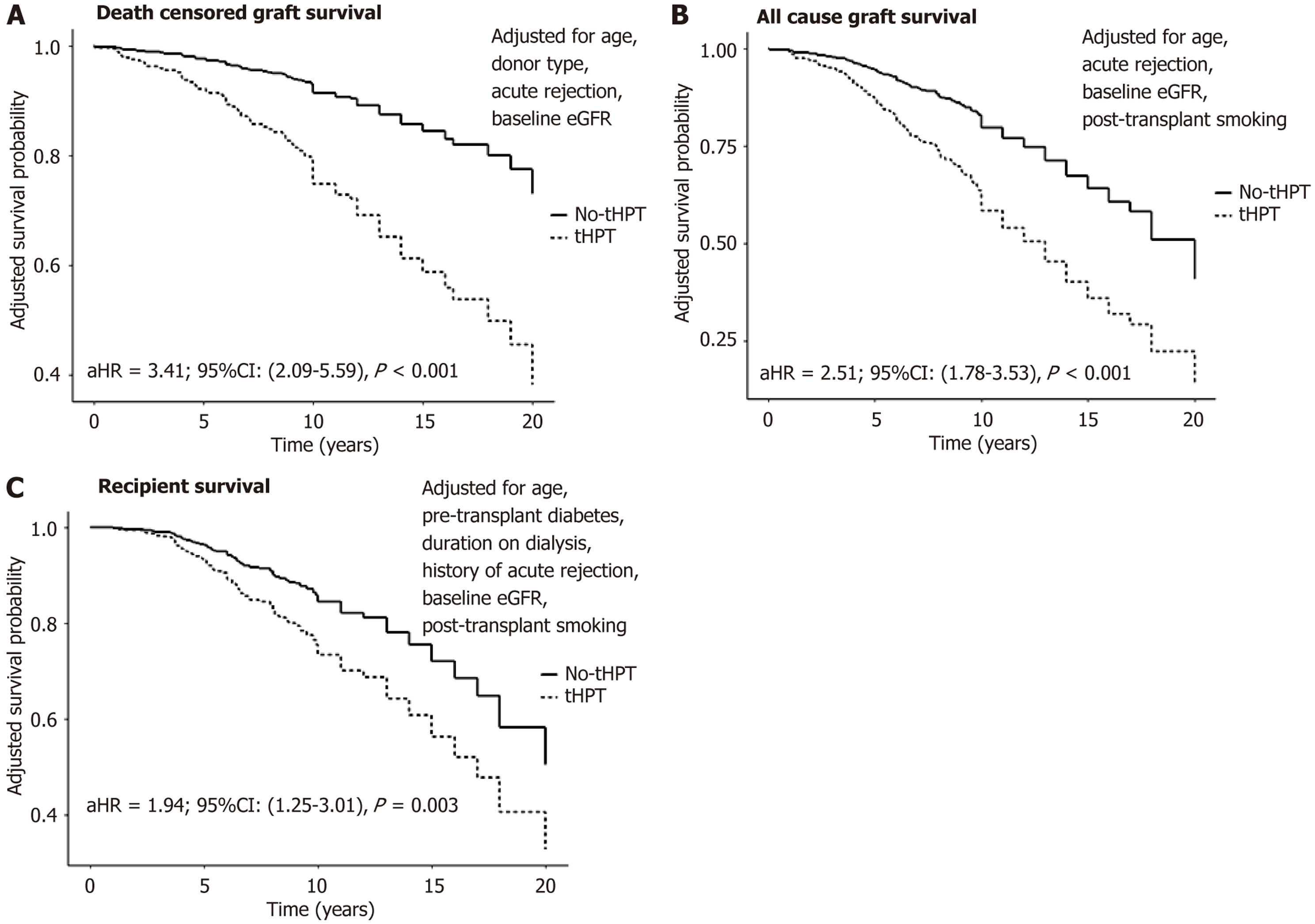

A total of 138 (15.5%) deaths and 87 (9.8%) graft losses were recorded over a median follow-up period of 7.3 years (88 months). The median death-censored graft survival was more than 20 years in both the tHPT and the non-tHPT group. The median recipient survival was more than 20 years in the no- tHPT group and 16 years in the tHPT group (Supplementary Figure 1).

In the unadjusted analysis, the 1-year, 5-year, 10-year, 15-year, and 20-year death censored allograft survival rates for recipients without PT-tHPT were 99.7%, 98%, 91%, 82%, and 68%, respectively. In contrast, recipients with PT-tHPT exhibited lower allograft survival rates of 99%, 89%, 73%, 58%, and 51% at the corresponding time points (log rank P < 0.001). Similarly, the unadjusted recipient survival rates at 1-year, 5-year, 10-year, 15-year, and 20-year were 100%, 95%, 82%, 73%, and 57%, respectively in recipients without PT-tHPT. In contrast, the survival rates in those who experienced PT-tHPT were 99%, 91%, 71%, 51%, and 35%, respectively (P = 0.006).

Figure 3 shows the impact of PT-tHPT on DCGS, all-cause graft survival and recipient survival adjusted for con

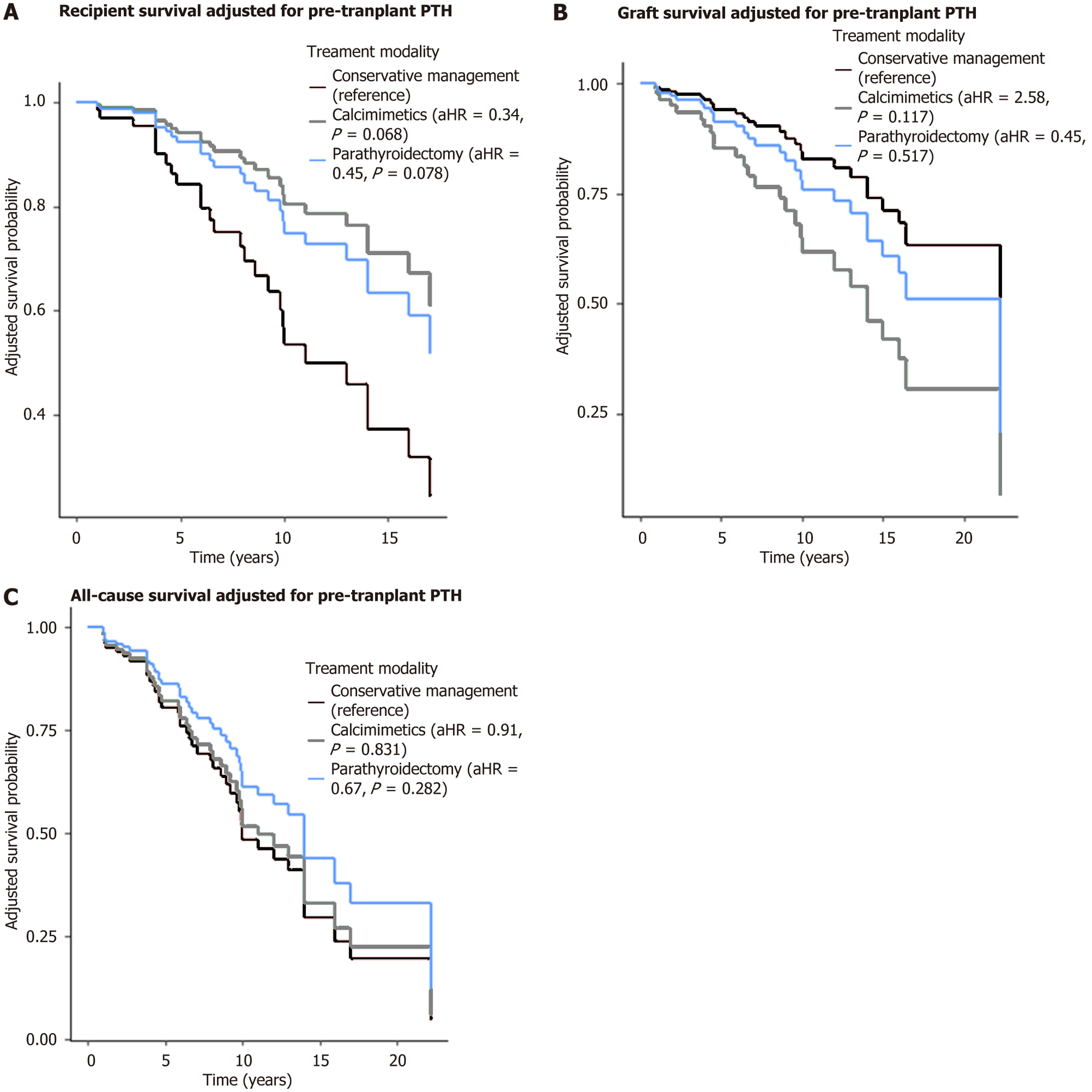

Table 3 and Figure 4 summarized the characteristics and outcomes of the recipients who experienced PT-tHPT stratified by their different treatment modalities.

| Variables | Conservative management (n = 40) | Calcimimetics (n = 42) | parathyroidectomy (n = 41) | Total (n = 123) | P value |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 52.1 (14.2) | 50.4 (11.6) | 49.6 (12.8) | 50.7 (12.8) | 0.679 |

| Duration of pre-transplant renal replacement therapy (months), median (IQR) | 24.0 (6.0-54.0) | 48.5 (24.0-66.0) | 24.0 (1.5-50.0) | 31.0 (7.0-57.0) | 0.049 |

| Baseline eGFR (mL/minute/1.73 m2), median (IQR) | 50.4 (37.0-59.2) | 53.5 (43.0-71.8) | 48.0 (38.0-59.0) | 50.8 (39.0-62.5) | 0.174 |

| Median pre-transplant calcium (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 2.5 (2.4-2.5) | 2.4 (2.3-2.5) | 2.5 (2.4-2.6) | 2.5 (2.4-2.6) | 0.184 |

| Median pre-transplant phosphate (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) | 1.7 (1.4-2.0) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) | 0.621 |

| Median pre-transplant parathyroid hormone (pmol/L), median (IQR) | 295.0 (138-478) | 643.5 (340-1163) | 374 (190-599) | 374 (216-719) | < 0.001 |

| The eGFR slope (mL/minute/year), median (IQR) | -1.02 (-1.94 to 0.38) | -1.78 (-3.80 to 0.01) | -1.09 (-3.21 to -0.18) | -1.27 (-3.67 to -0.09) | 0.378 |

| History of acute rejection | 4 (10.5) | 5 (12.5) | 10 (24.4) | 19 (16.0) | 0.186 |

Three management strategies were employed to address PT-tHPT among the recipients. Of the total recipients who experienced PT-tHPT, a third (n = 40) were managed conservatively, a third (n = 42) were treated with calcimimetics (cinacalcet), and a third (n = 41) underwent parathyroidectomy (with 22 having a partial parathyroidectomy and 19 undergoing total parathyroidectomy). Data on treatment modality was not available for two recipients. There were no significant differences in recipients’ age, baseline eGFR and pretransplant bone profile among the treatment groups. Of the three groups, the calcimimetic group had spent the longest period receiving dialysis and had the highest median pretransplant PTH levels. Amongst the three modalities of treatment, acute rejection, DCGS and ACGS did not differ significantly although the parathyroidectomy group had numerically higher rejection rates, lower DCGS and lower ACGS.

Although there was a trend toward lower recipient survival in the conservative group (Figure 4A), this difference was not statistically significant and should be interpreted with caution. The observed pattern may reflect underlying diff

In the sensitivity analysis, we applied a Cox regression analysis to the data to assess graft, and recipient outcomes after excluding recipients who developed PT-tHPT after the 3rd year of transplantation. The result was not different from that obtained with all the occurrences of PT-tHPT (Supplementary Figure 2).

The observed incidence of PT-tHPT in our cohort was 14%, lower than previously reported rates ranging from 17% to 86%[11,12,14]. Among affected patients, 15% experienced graft loss, and 24% died over a median follow-up of 7.3 years.

Significant risk factors for PT-tHPT included older age, elevated pretransplant serum calcium and PTH levels, longer dialysis duration, prolonged ischemia time, a history of acute rejection, and a faster eGFR decline.

Notably, Asian ethnicity was negatively associated with PT-tHPT, with an OR suggesting a potentially protective effect. While the biological plausibility of this association is not immediately clear, several hypotheses may explain this finding. Cultural and dietary factors such as higher intake of plant-based foods, lower dietary phosphorus load, or differing patterns of vitamin D intake and level exposure to ultraviolet light due to cultural factors may influence post-transplant mineral metabolism and warrant further exploration. Additionally, genetic differences, including variations in genes regulating calcium-phosphate homeostasis or PTH signalling pathways, may contribute to the observed effect. Although our dataset did not include detailed dietary or genetic information, these potential explanations will be important to investigate in future studies. We therefore recommend caution in interpreting this association and suggest that future research explore ethnic-specific risk factors in more detail.

The strong correlation between pretransplant serum calcium and PTH levels in our study aligns with prior findings. Hong et al[15] previously identified pretransplant intact PTH, serum calcium levels, and dialysis duration as key factors associated with post-transplant HPT. The link between prolonged dialysis and PT-tHPT supports the idea that chronic parathyroid gland stimulation during the pretransplant period leads to autonomous HPT post-transplant. The sHPT in advanced CKD results from multiple factors, including hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcaemia, low 1,25(OH)2D levels, and skeletal resistance to PTH. These factors result in continuous stimulation of PTH synthesis and secretion. The parathyroid hyperplasia that develops is initially diffuse and polyclonal and usually responds to vitamin D therapy and calcimimetics. However, with prolonged sHPT, over time, there is down regulation of vitamin D receptors and calcium-sensing receptors in the parathyroid tissue, and hyperplasia becomes monoclonal and nodular in nature[16,17]. In such patients, PTH synthesis and secretion become autonomous with minimal response to therapeutic agents. This is often associated with hypercalcemia. Parathyroid imaging often shows that diffuse polyclonal hyperplastic glands are significantly smaller than nodular monoclonal glands[18].

With successful transplantation and higher eGFR, most of these stimuli of parathyroid hyperplasia abate. This often leads to a gradual decline in PTH concentrations. However, reports have shown that up to 25%-80% of patients still have inappropriately high PTH beyond 1-year post transplant[16]. Pre-transplant cinacalcet use, development of nodular hyperplasia, and dialysis vintage are associated with high PTH levels after transplantation. Thus, in transplant recipients, the clinical manifestations of HPT resemble primary HPT and are characterised by hypercalcemia and hypophosphatemia due to the effects of PTH on the kidney. Whereas nontransplant patients with CKD with HPT typically have hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcaemia.

In multivariable analysis, a higher eGFR slope was associated with a reduced risk of PT-tHPT (OR = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.87-0.96, P = 0.001), indicating that preserved or improving renal function is protective. This association may be explained by the development or persistence of sHPT in the context of worsening allograft function. Better-preserved or improving graft function may reduce the biochemical stimuli, such as hyperphosphatemia and impaired vitamin D metabolism, which drive PTH secretion. In contrast, declining graft function perpetuates mineral dysregulation, contributing to sus

Our most significant finding was the association between PT-tHPT and an increased risk of graft loss and recipient mortality. Recipients with PT-tHPT had a 3.4-fold higher risk of death-censored graft loss, a 2.5-fold higher risk of all-cause graft loss, and a 1.9-fold higher risk of recipient death compared to those without PT-tHPT. These results mirror previous studies[15] and emphasize the importance of early intervention and proactive management[19-23].

The exact mechanisms linking PT-tHPT to graft loss and mortality remain unclear. However, evidence suggests that persistent hypercalcemia in PT-tHPT contributes to renovascular calcification, nephrocalcinosis, and progressive graft dysfunction[23,24]. Elevated PTH levels also directly promote systemic vascular and cardiac complications, including arterial calcification, hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, and cardiovascular dysfunction. These effects are mediated through increased intracellular calcium, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation, ultimately leading to cardiac myocyte necrosis[21,25]. Moreover, PTH upregulates pro-atherosclerotic and pro-inflammatory mediators such as receptors for advanced glycation end products, interleukin-6, and vascular endothelial growth factor, which may contribute to vascular remodelling and atherosclerosis[24,26,27].

Beyond these established pathways, recent evidence highlights a complex interplay between PTH and FGF23. PTH stimulates FGF23 production in bone, while FGF23, in turn, suppresses PTH secretion via FGFR-Klotho signalling in the parathyroid glands[28]. In patients with CKD or post-transplant mineral dysregulation, this feedback loop may become impaired, particularly due to reduced Klotho expression in hyperplastic parathyroid tissue, contributing to sustained PTH elevation and resistance to FGF23. This dysregulation may further exacerbate phosphate retention, vascular cal

The optimal management strategy for PT-tHPT remains unclear. In our cohort, three treatment approaches were used, but patient outcomes did not significantly differ between treatment modalities. However, recipient survival appeared numerically lower in the conservatively managed group. These findings are consistent with the EVOLVE trial, which examined cinacalcet use in dialysis patients and found no survival benefit compared to placebo[31].

Studies comparing surgical and medical management of PT-tHPT have produced mixed results. Some have reported a survival advantage with parathyroidectomy over medical therapy in KTRs[2,32], while others found no significant difference[26]. A systematic review by Dulfer et al[33], noted a higher biochemical cure rate with parathyroidectomy but no clear difference in graft survival compared to cinacalcet therapy. In contrast, a retrospective single-centre study by Finnerty et al[34], reported improved graft survival in patients treated with parathyroidectomy vs those receiving cinacalcet. However, these studies are not directly comparable. Dulfer et al’s review[33] included 47 studies, most of which were observational and heterogeneous in design, patient populations, treatment protocols, and follow-up duration. Due to this heterogeneity, the authors were unable to conduct a meta-analysis, which limits the strength of the con

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, its observational design precludes definitive causal inference, and residual confounding may persist despite adjustment for measured baseline characteristics.

Second, serum vitamin D levels were not routinely measured in our transplant population, and data on calcium and vitamin D supplementation were inconsistently recorded. These unmeasured variables may have influenced PTH levels and treatment responses, limiting our ability to account for their potential confounding effects.

Third, accurately characterising long-term immunosuppression exposure was challenging due to frequent regimen modifications. CNI doses vary with therapeutic drug monitoring, antimetabolites are often interrupted due to infections, cytopenias, or malignancy, and glucocorticoids may be reintroduced in selected cases. These dynamic changes limit the precision with which immunosuppressive burden could be assessed in relation to PT-tHPT outcomes.

Fourth, treatment allocation was not randomised. Patients in the calcimimetic group had higher baseline PTH levels, and other differences in clinical characteristics may have influenced the choice of therapy and subsequent outcomes. Importantly, propensity score methods were not employed to adjust for these differences, and unmeasured confounders such as frailty, comorbidity burden, and clinician-driven selection bias may have affected treatment comparisons.

Fifth, this was a single-centre study based in Northwest England and included transplants performed between 2000 and 2020. These temporal and geographical constraints may limit the generalisability of the findings to other populations or clinical settings.

Sixth, patients with early graft loss (within three months post-transplant) were excluded from the analysis. This may have introduced survivorship bias and resulted in underrepresentation of individuals with early post-transplant complications, who may follow different clinical trajectories than those with long-term stable graft function. As PT-tHPT is typically a long-term complication, our findings may not fully reflect the spectrum of transplant-related mineral-bone disorders.

Finally, the absence of statistically significant survival differences between treatment modalities may reflect the influence of unmeasured confounding. Given that important clinical characteristics affecting both therapy selection and outcomes were not systematically recorded or adjusted for, the findings should be interpreted with caution. This underscores the need for prospective, longitudinal, and ideally randomised studies incorporating standardised data collection to better evaluate the comparative effectiveness of surgical and medical management strategies in PT-tHPT.

In conclusion, our findings underscore the burden of PT-tHPT in KTRs, emphasizing its adverse impact on allograft and patient survival. The study emphasizes the significance of pretransplant management of sHPT, advocating for early inter

| 1. | Hariharan S, Israni AK, Danovitch G. Long-Term Survival after Kidney Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:729-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 87.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Palumbo VD, Palumbo VD, Damiano G, Messina M, Fazzotta S, Lo Monte G, Lo Monte AI. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism: a review. Clin Ter. 2021;172:241-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Das S, Majumder M, Das D, Chowdhury N, Das A, Das K, Fardous J, Hasan MJ. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Secondary Hyperparathyroidism among CKD Patients and Correlation with Different Laboratory Parameters. Mymensingh Med J. 2022;31:1084-1092. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Hyder R, Sprague SM. Secondary Hyperparathyroidism in a Patient with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:1041-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yang RL, Freeman K, Reinke CE, Fraker DL, Karakousis GC, Kelz RR, Doyle AM. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism in kidney transplant recipients: characteristics of patients selected for different treatment strategies. Transplantation. 2012;94:70-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Delos Santos R, Rossi A, Coyne D, Maw TT. Management of Post-transplant Hyperparathyroidism and Bone Disease. Drugs. 2019;79:501-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xu Y, Evans M, Soro M, Barany P, Carrero JJ. Secondary hyperparathyroidism and adverse health outcomes in adults with chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14:2213-2220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schumock GT, Andress D, E Marx S, Sterz R, Joyce AT, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Impact of secondary hyperparathyroidism on disease progression, healthcare resource utilization and costs in pre-dialysis CKD patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3037-3048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Littbarski SA, Kaltenborn A, Gwiasda J, Beneke J, Arelin V, Schwager Y, Stupak JV, Marcheel IL, Emmanouilidis N, Jäger MD, Scheumann GFW, Klempnauer J, Schrem H. Timing of parathyroidectomy in kidney transplant candidates with secondary hyperparathryroidism: effect of pretransplant versus early or late post-transplant parathyroidectomy. Surgery. 2018;163:373-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Reinhardt W, Bartelworth H, Jockenhövel F, Schmidt-Gayk H, Witzke O, Wagner K, Heemann UW, Reinwein D, Philipp T, Mann K. Sequential changes of biochemical bone parameters after kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:436-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alqahtani S. Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism: A Narrative Mini-Review. Majmaah J Heal Sci. 2020;8:140. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Sutton W, Chen X, Patel P, Karzai S, Prescott JD, Segev DL, McAdams-DeMarco M, Mathur A. Prevalence and risk factors for tertiary hyperparathyroidism in kidney transplant recipients. Surgery. 2022;171:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wolf M, Weir MR, Kopyt N, Mannon RB, Von Visger J, Deng H, Yue S, Vincenti F. A Prospective Cohort Study of Mineral Metabolism After Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation. 2016;100:184-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Green RL, Karhadkar SS, Kuo LE. Missed Opportunities to Diagnose and Treat Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism After Transplant. J Surg Res. 2023;287:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hong N, Lee J, Kim HW, Jeong JJ, Huh KH, Rhee Y. Machine Learning-Derived Integer-Based Score and Prediction of Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism among Kidney Transplant Recipients: An Integer-Based Score to Predict Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:1026-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vangala C, Pan J, Cotton RT, Ramanathan V. Mineral and Bone Disorders After Kidney Transplantation. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tokumoto M, Tsuruya K, Fukuda K, Kanai H, Kuroki S, Hirakata H. Reduced p21, p27 and vitamin D receptor in the nodular hyperplasia in patients with advanced secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1196-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Matsuoka S, Tominaga Y, Sato T, Uno N, Hiramitu T, Goto N, Nagasaka T, Uchida K. Relationship between the dimension of parathyroid glands estimated by ultrasonography and the hyperplastic pattern in patients with renal hyperparathyroidism. Ther Apher Dial. 2008;12:391-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dream S, Chen H, Lindeman B. Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism: Why the Delay? Ann Surg. 2021;273:e120-e122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pihlstrøm H, Dahle DO, Mjøen G, Pilz S, März W, Abedini S, Holme I, Fellström B, Jardine AG, Holdaas H. Increased risk of all-cause mortality and renal graft loss in stable renal transplant recipients with hyperparathyroidism. Transplantation. 2015;99:351-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gruson D. PTH and cardiovascular risk. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2021;82:149-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Isakov O, Ghinea R, Beckerman P, Mor E, Riella LV, Hod T. Early persistent hyperparathyroidism post-renal transplantation as a predictor of worse graft function and mortality after transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2020;34:e14085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Crepeau P, Chen X, Udyavar R, Morris-Wiseman LF, Segev DL, McAdams-DeMarco M, Mathur A. Hyperparathyroidism at 1 year after kidney transplantation is associated with graft loss. Surgery. 2023;173:138-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rashid G, Bernheim J, Green J, Benchetrit S. Parathyroid hormone stimulates endothelial expression of atherosclerotic parameters through protein kinase pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1215-F1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yuen NK, Ananthakrishnan S, Campbell MJ. Hyperparathyroidism of Renal Disease. Perm J. 2016;20:15-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Schlüter KD, Piper HM. Cardiovascular actions of parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:34-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rashid G, Bernheim J, Green J, Benchetrit S. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the endothelial expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38:798-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ovejero D, Hartley IR, de Castro Diaz LF, Theng E, Li X, Gafni RI, Collins MT. PTH and FGF23 Exert Interdependent Effects on Renal Phosphate Handling: Evidence From Patients With Hypoparathyroidism and Hyperphosphatemic Familial Tumoral Calcinosis Treated With Synthetic Human PTH 1-34. J Bone Miner Res. 2022;37:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lanske B, Razzaque MS. Molecular interactions of FGF23 and PTH in phosphate regulation. Kidney Int. 2014;86:1072-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | De Buyzere ML, Delanghe JR. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and the quest for the Holy Grail in heart failure: will the Crusaders be forced to surrender? Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:710-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | EVOLVE Trial Investigators; Chertow GM, Block GA, Correa-Rotter R, Drüeke TB, Floege J, Goodman WG, Herzog CA, Kubo Y, London GM, Mahaffey KW, Mix TC, Moe SM, Trotman ML, Wheeler DC, Parfrey PS. Effect of cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2482-2494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 671] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 46.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rivelli GG, Lima ML, Mazzali M. Therapy for persistent hypercalcemic hyperparathyroidism post-renal transplant: cinacalcet versus parathyroidectomy. J Bras Nefrol. 2020;42:315-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dulfer RR, Franssen GJH, Hesselink DA, Hoorn EJ, van Eijck CHJ, van Ginhoven TM. Systematic review of surgical and medical treatment for tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Br J Surg. 2017;104:804-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Finnerty BM, Chan TW, Jones G, Khader T, Moore M, Gray KD, Beninato T, Watkins AC, Zarnegar R, Fahey TJ 3rd. Parathyroidectomy versus Cinacalcet in the Management of Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism: Surgery Improves Renal Transplant Allograft Survival. Surgery. 2019;165:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/