Published online Jun 18, 2024. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v14.i2.91052

Revised: January 29, 2024

Accepted: March 7, 2024

Published online: June 18, 2024

Processing time: 176 Days and 8.9 Hours

The impact of social determinants of health in allogeneic transplant recipients in low- and middle-income countries is poorly described. This observational study analyzes the impact of place of residence, referring institution, and transplant cost coverage (out-of-pocket vs government-funded vs private insurance) on outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT) in two of Mexico's largest public and private institutions.

To evaluate the impact of social determinants of health and their relationship with outcomes among allogeneic transplant recipients in Mexico.

In this retrospective cohort study, we included adolescents and adults ≥ 16 years who received a matched sibling or haploidentical transplant from 2015-2022. Participants were selected without regard to their diagnosis and were sourced from both a private clinic and a public University Hospital in Mexico. Three payment groups were compared: Out-of-pocket (OOP), private insurance, and a federal Universal healthcare program “Seguro Popular”. Outcomes were compared between referred and institution-diagnosed patients, and between residents of Nuevo Leon and out-of-state. Primary outcomes included overall survival (OS), categorized by residence, referral, and payment source. Secondary outcomes encompassed early mortality, event-free-survival, graft-versus-host-relapse-free survival, and non-relapse-mortality (NRM). Statistical analyses employed appropriate tests, Kaplan-Meier method, and Cox proportional hazard regression modeling. Statistical software included SPSS and R with tidycmprsk library.

Our primary outcome was overall survival. We included 287 patients, n = 164 who lived out of state (57.1%), and n = 129 referred from another institution (44.9%). The most frequent payment source was OOP (n = 139, 48.4%), followed by private insurance (n = 75, 26.1%) and universal coverage (n = 73, 25.4%). No differences in OS, event-free-survival, NRM, or graft-versus-host-relapse-free survival were observed for patients diagnosed locally vs in another institution, nor patients who lived in-state vs out-of-state. Patients who covered transplant costs through private insurance had the best outcomes with improved OS (median not reached) and 2-year cumulative incidence of NRM of 14% than patients who covered costs OOP (Median OS and 2-year NRM of 32%) or through a universal healthcare program active during the study period (OS and 2-year NRM of 19%) (P = 0.024 and P = 0.002, respectively). In a multivariate analysis, payment source and disease risk index were the only factors associated with overall survival.

In this Latin-American multicenter study, the site of residence or referral for alloHSCT did not impact outcomes. However, access to healthcare coverage for alloHSCT was associated with improved OS and reduced NRM.

Core Tip: In our comprehensive analysis of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT) outcomes in Mexico, we underscore the pivotal role of insurance coverage. Patients with private insurance had superior survival rates compared to those relying on out-of-pocket or government programs. Intriguingly, geographical residence and referral sources did not significantly influence outcomes. This study underscores the profound implications of financial barriers in healthcare access and the urgent need for policy interventions. Our findings stress the importance of addressing socioeconomic disparities and emphasize the role of insurance status in enhancing alloHSCT outcomes in regions like Latin America.

- Citation: Gómez-De León A, López-Mora YA, García-Zárate V, Varela-Constantino A, Villegas-De Leon SU, González-Leal XJ, del Toro-Mijares R, Rodríguez-Zúñiga AC, Barrios-Ruiz JF, Mingura-Ledezma V, Colunga-Pedraza PR, Cantú-Rodríguez OG, Gutiérrez-Aguirre CH, Tarín-Arzaga L, González-López EE, Gómez-Almaguer D. Impact of payment source, referral site, and place of residence on outcomes after allogeneic transplantation in Mexico. World J Transplant 2024; 14(2): 91052

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v14/i2/91052.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v14.i2.91052

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines social determinants of health as the "non-medical factors that influence outcomes"[1]. According to the WHO, these factors can account for 30%-55% of health outcomes, estimating that their contributions are more important than lifestyle choices or healthcare itself[1]. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT) for hematological malignancies is a complex and expensive procedure that requires special pre- and post-transplant care. Not surprisingly, there is evidence that social determinants of health impact outcomes after alloHSCT. Most available data come from retrospective cohort analyses in the United States and other high-income countries. The impact of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status on outcomes after alloHSCT has been described in this setting. Low socioeconomic status has been reported to correlate with a higher risk of all-cause mortality and non-relapse mortality (NRM)[2]. Other factors associated with better quality of life and activity level include the ability to work, level of education, and community health status[3,4].

To our knowledge, reports from Latin America on the influence of social determinants on outcomes after alloHSCT do not exist. The payment source in Latin America and other low and middle-income countries is a challenge, with most of the population relying on government-funded health systems that are limited in capacity. The Mexican health system consists of three main components: (1) Employment-based healthcare (40.4%); (2) public assistance services for the uninsured (43.5%); and (3) a private sector composed of out-of-pocket payments from patients and private insurance companies. Government-funded healthcare accounts for 58% of all healthcare financing, and less than 7.5% of the population has access to private insurance. The rest comes from out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses incurred by patients and their families[5,6].

Additionally, centers throughout the region are forced to refer patients to transplant centers in major cities due to a lack of local resources, forcing patients to travel and cover those costs, potentially increasing the risk of poorer outcomes. Specifically, reports analyzing the impact of the payment source, place of residence, and referral site are lacking in our setting. Therefore, our primary objective was to examine the association of the source of transplant payment, referral site, and place of residence on overall survival after alloHSCT for malignant hematological disorders in Mexico.

This retrospective cohort included patients from two large transplant centers in Mexico: a private clinic and a public University Hospital with a FACT-JACIE accredited outpatient transplantation program. All patients ≥ 16 years old with hematologic malignancies that underwent alloHSCT from 2015-2022 were included. The University Hospital is open to all regardless of place of residence, referring institution, and healthcare access, but it requires OOP payment coverage to fund the procedure. From 2015 to 2019, a Universal healthcare program, "Seguro Popular," covered HSCT in our institution for otherwise uninsured patients across indications and populations but was terminated in 2019 by the current federal administration and is no longer available locally. Therefore, data from patients in the federal coverage program group, was exclusively from the period spanning 2015-2019, as no patients were eligible for coverage under the "Seguro Popular" program after 2019. The private clinic receives patients with private insurance and OOP regardless of the place of residence or referring institution. Patients are cared for by five transplant physicians who all trained at the university hospital; three worked in both institutions during the study period, sharing common practices and procedures. Thus, the outcomes of three payment coverage groups are compared in the entire cohort: OOP, privately insured patients, and patients who received care through the federal Universal healthcare program (2015-2019). Similarly, the outcomes of patients referred for transplant from another institution were compared to those diagnosed and treated in each institution before HSCT. Finally, the outcomes of patients who lived in Nuevo Leon vs those from out of state were also compared. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of both institutions and was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conditioning regimens were similar in both medical centers. They included the following combinations: cyclophosphamide fludarabine and melphalan 140-200 mg/m2, CyFlu plus busulfan (Bu) 8-12 mg/kg, CyFlu anti-thymocyte globulin for non-myeloablative regimens with or without 2 Gy total body irradiation for haploidentical transplant recipients. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis mainly included post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCy) plus either PO cyclosporine or tacrolimus (CsA) and mycophenolate or CsA or tacrolimus plus methotrexate (CNI + MTX) tapered between day 100 until day 180 or after 1 year in patients with aplastic anemia.

Matched sibling donors were preferred across indications. During the study period, haploidentical family donors were considered acceptable alternatives for patients without matched sibling donors across indications since unrelated donors are highly expensive and of limited access in our country. When multiple haploidentical donors were available, younger donors with ABO compatibility and similar CMV seropositivity were selected. Donors were mobilized with filgrastim for 4 d, 10 ug/kg per day, and underwent peripheral blood apheresis with a target harvest of ≥ 5 × 106 CD34+ cells per kg of recipient weight. Cells were refrigerated and infused fresh without further manipulation on day 0.

In the University Hospital, most patients underwent alloHSCT following a day-hospital outpatient strategy with ambulatory conditioning, cell infusion, and follow-up care extensively described by Gómez-Almaguer et al[7] with hospitalization indicated for complications associated with conditioning regimen toxicity and the need for intensive supportive care, infectious complications, or daily transfusion requirements. In the private setting, patients underwent a conventional in-patient strategy in a bone marrow transplant unit equipped with isolation rooms, independent air and water filtration systems, and positive pressure. Infectious disease prophylaxis was identical in both centers. It consisted of IV or PO levofloxacin 500 mg QD, itraconazole 100 mg BID or voriconazole 200 mg BID, acyclovir 400 mg BID, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 800/160 mg thrice weekly after engraftment. Filgrastim 5 µg/kg daily or pegfilgrastim 6 mg single dose was administered after day +5 until engraftment.

Our primary outcome was overall survival (OS) according to the place of residence (in-state vs out-of-state), referral (local diagnosis and treatment vs referral from another institution for HSCT), and transplant cost payment source (OOP vs universal coverage program vs private insurance). Secondary outcomes included early mortality, event-free survival (EFS), graft-versus-host-relapse-free survival (GRFS), and non-relapse mortality (NRM). OS was defined as the time between transplant and last follow-up or death. EFS was defined as the time between transplant and death, or relapse or progression of the underlying disease or last follow-up. GRFS was defined as the time between transplant and death, relapse or progression of the underlying disease, or the diagnosis of acute grade ≥ 3 GVHD or chronic GVHD requiring systemic treatment[8].

Patients' demographic and diagnostic characteristics, including sex, age, hematopoietic cell comorbidity index[9], and disease risk index (DRI)[10], were compared across interest groups. Similarly, transplant characteristics and immediate outcomes like donor HLA match, conditioning intensity[11], CD34+ cells infused, GVHD prophylaxis, neutrophil and platelet recovery, graft failure[12], and incidence and severity of acute or chronic GVHD were compared. Categorical variables were contrasted with the chi-square test, and continous variables were compared with Student's t-test, ANOVA, or the Mann Whitney U or Kruskal Wallis test according to normality. Survival outcomes were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression modeling was performed to assess the potential impact of relevant co-variables on OS. The cumulative incidence of NRM was analyzed by considering death after relapse as a competing risk. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS for Mac version 26 and R software and the tidycmprsk library. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Hector A Vaquera-Alfaro.

Two hundred and eighty-seven patients were included, mostly a young population without comorbidities, n = 214 from the public and n = 73 from the private institution. Acute leukemia was the most common diagnosis, followed by aplastic anemia (n = 36, 12.5%) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n = 29, 10.1%) (Table 1). Regarding disease stage, n = 127 (44.2%) had a high or very high DRI with a median of 2 prior lines of treatment. Most patients received a haploidentical graft (n = 176, 61.3%); half received myeloablative conditioning (49.8%), and all patients received peripheral blood grafts. One hundred and sixty-four lived out of state (57.1%), and n = 129 were referred from another institution for HCT. Seventeen patients came from another country, most frequently from Central and South America. The most frequent payment source was OOP (n = 139, 48.4%), followed by private insurance (n = 75, 26.1%) and universal coverage (n = 73, 25.4%). The demographic information of our patient population is described in Table 1. The median follow-up of survivors/patients was 19.4 months.

| Variable | n | % | |

| Sex | Male | 168 | 58.6 |

| Female | 119 | 41.5 | |

| Age | Median (years) | 35 | (16-79) |

| Country of origin | Mexico | 270 | 94 |

| Other | 17 | 6 | |

| State of origin | Nuevo Leon | 123 | 42.9 |

| Other | 164 | 57.1 | |

| Institution | Referral | 165 | 57.5 |

| Local | 122 | 42.5 | |

| Diagnosis | AML | 77 | 26.8 |

| ALL | 76 | 26.4 | |

| AA | 36 | 12.5 | |

| NHL | 29 | 10.1 | |

| MDN | 25 | 8.7 | |

| HL | 17 | 5.9 | |

| CML | 10 | 3.4 | |

| CMML | 6 | 2.1 | |

| PMF | 4 | 1.4 | |

| CLL | 4 | 1.4 | |

| MM | 3 | 1 | |

| Donor | Matched sibling | 111 | 38.7 |

| Haploidentical | 176 | 61.3 | |

| DRI | Non-malignant | 36 | 12.6 |

| Intermediate | 117 | 40.8 | |

| High | 100 | 34.8 | |

| Very high | 27 | 9.4 | |

| HCT-CI | Median | 0 | (0-5) |

| Treatment lines | Median | 2 | (0-6) |

| Payment source | Out-of-pocket | 139 | 48.4 |

| Private insurance | 75 | 26.1 | |

| Universal coverage | 73 | 25.4 |

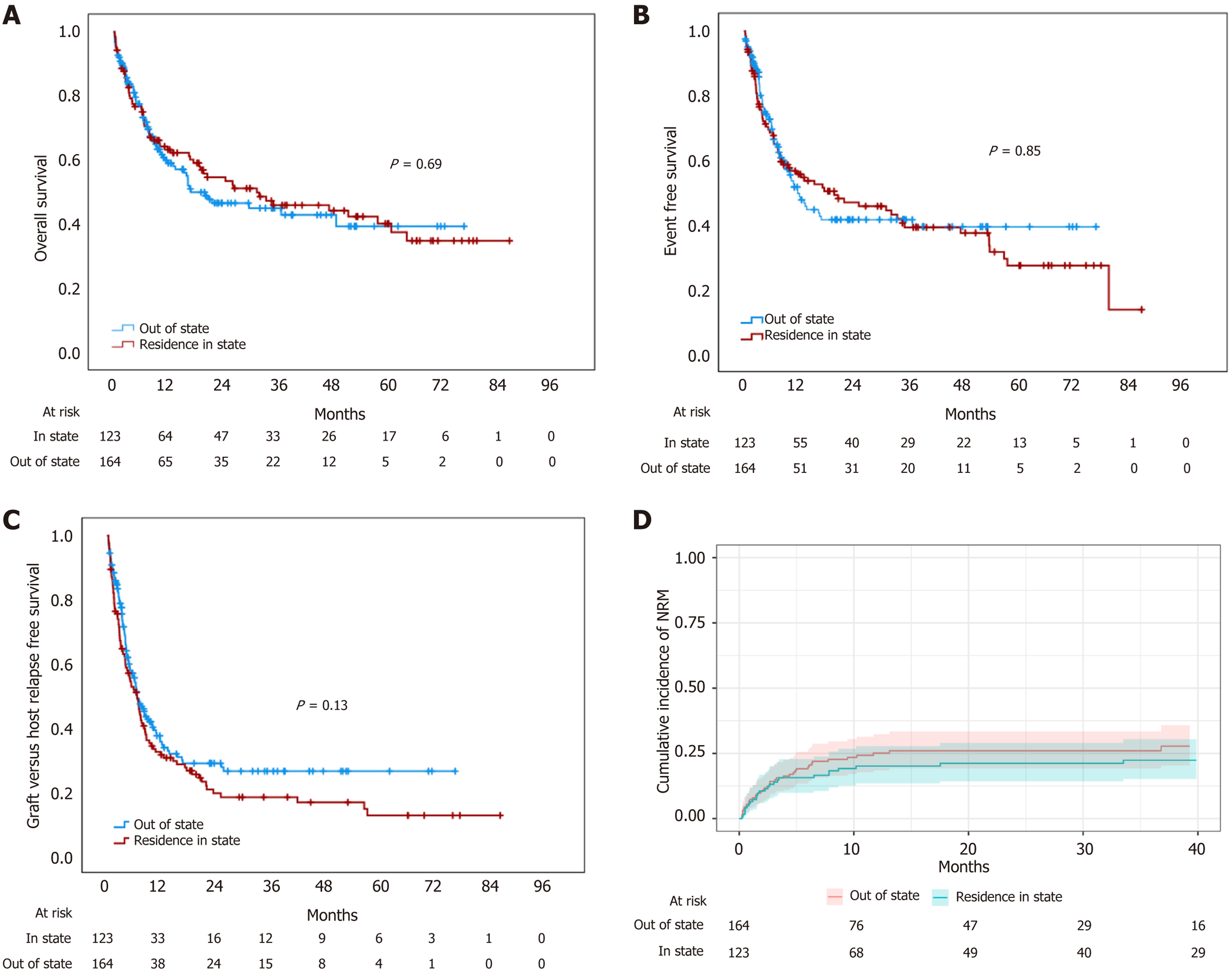

Out-of-state patients covered transplant costs more frequently OOP (56.7% vs 37.4%; P = 0.003) and had a worse DRI than local patients (high or very high 50.6% vs 35.7%; P = 0.02). No differences in HCT-CI, CD34 cells, myeloid recovery, aGVHD rates or early mortality were observed. Out-of-state patients received more frequent PTCy prophylaxis (81% vs 69.9%; P = 0.02) and experienced lower rates of severe cGVHD (2.4% vs 12.2%; P = 0.003). No statistical differences in OS, EFS, GRFS, or NRM were documented. Median OS was 31 months in state residents (95%CI: 1.9-32) vs 16.9 months in out-of-state residents (95%CI: 8.3-54.6) (Figure 1), with median EFS of 19.7 months (95%CI: 3.9-36.1) vs 12.1 (95%CI: 7.4-16.8) and identical median GRFS of 6.6 months (95%CI: 4.8-8.5 and 4.7-8.4, respectively). Two-year NRM was also similar, 26% (95%CI: 19%-33%) in out-of-state patients vs 21% (95%CI: 14%-29%) for in-state patients (P = 0.4). Place of residence was not associated with OS in the univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2).

| HR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Univariate analysis | ||||

| Age | Continuous | 1 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.77 |

| Sex | Female | 1 | 0.71-1.4 | 0.98 |

| DRI | Benign | 0.66 | 0.36-1.19 | 0.02 |

| Low | 0.15 | 0.02-1.08 | ||

| Intermediate | 0.66 | 0.46-0.94 | ||

| Treatment lines | Continuous | 1.13 | 0.99-1.28 | 0.06 |

| HCT-CI | Continuous | 1.1 | 0.87-1.3 | 0.56 |

| Place of residence | Out of state | 0.94 | 0.67-1.31 | 0.7 |

| Reference | Non-local | 0.99 | 0.71-1.38 | 0.95 |

| Coverage | Universal | 0.76 | 0.51-1.13 | 0.02 |

| Private | 0.55 | 0.35-0.86 | ||

| Donor | Haploidentical | 1.48 | 1.03-2.1 | 0.03 |

| Conditioning | NMA | 0.94 | 0.53-1.67 | 0.92 |

| RIC | 1.1 | 0.73-1.53 | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis | PTCy | 1.6 | 0.89-3.01 | 0.01 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||

| DRI | Benign | 0.64 | 0.3-1.37 | 0.25 |

| Low | 0.15 | 0.02-1.12 | 0.06 | |

| Intermediate | 0.57 | 0.32-1 | 0.05 | |

| High | 0.9 | 0.52-1.58 | 0.72 | |

| Coverage | Federal | 0.86 | 0.58-1.29 | 0.46 |

| Private | 0.49 | 0.31-0.77 | 0.002 | |

| Donor | Haploidentical | 0.93 | 0.56-1.53 | 0.78 |

| GVDH prophylaxis | PTCy | 1.64 | 0.89-3 | 0.11 |

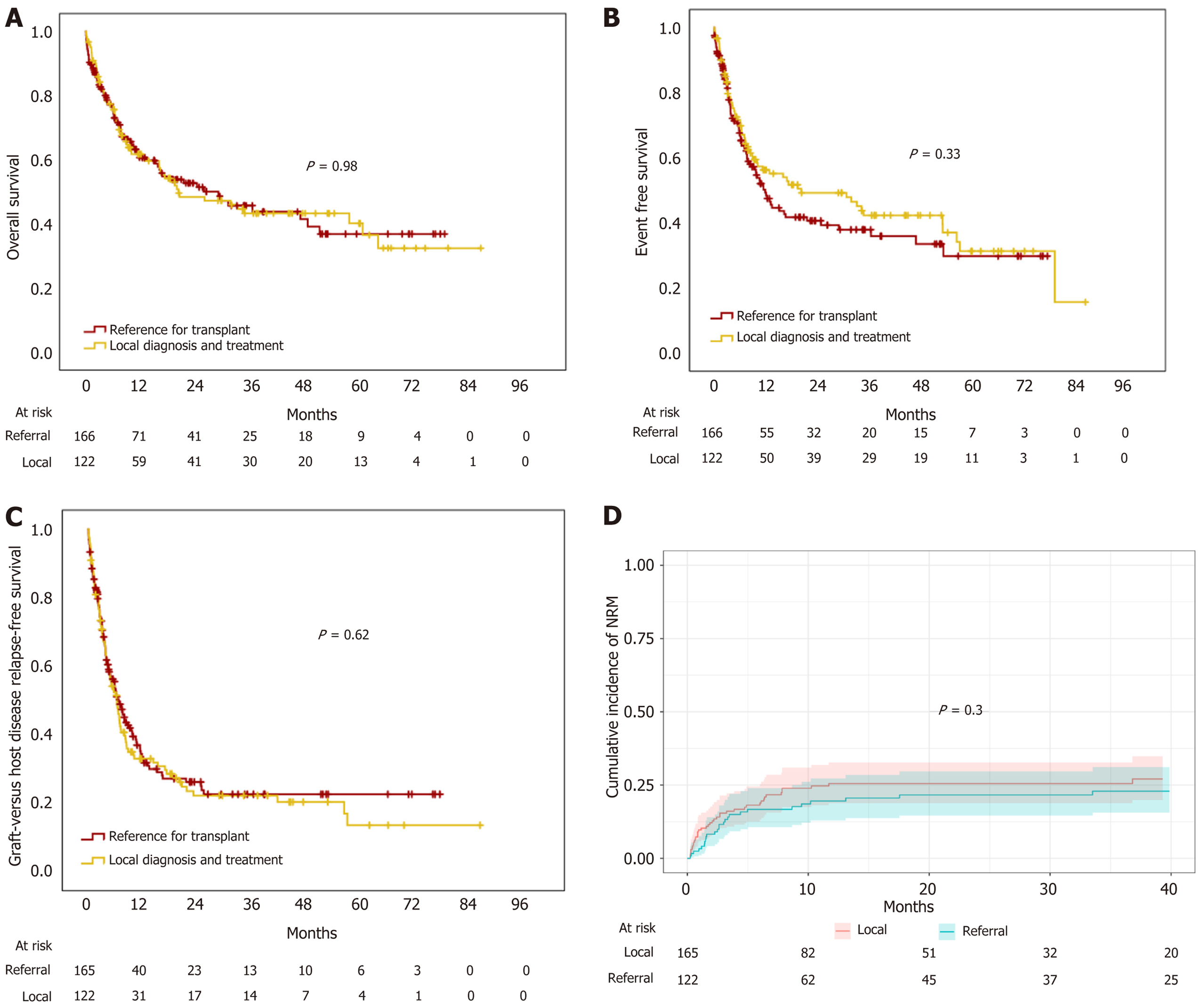

Patients who were diagnosed and treated elsewhere and referred to our institution for HCT had higher risk disease than local patients (high or very high DRI 49.4% vs 36.9%; P = 0.03). Also, they were more likely to reside out of state than local patients (78% vs 28.7%; P < 0.001) and cover transplant costs out-of-pocket (61.2% vs 31.1% P < 0.001). Patients had similar rates of aGVHD but higher rates of grades 3-4 acute GVHD (16.4% vs 6.8%; P = 0.03). No differences in engraftment, myeloid recovery, and early mortality in local vs referred patients were observed. Similarly, no statistical differences in OS, EFS, GRFS, or NRM were documented. Median OS was 20 months (95%CI: 5.3-35.6) vs 29.3 (95%CI: 14-44), median EFS was 20.6 months (95%CI: 2.2-38.9) vs 12.1 months (95%CI: 9.1-15.1) and median GRFS was 6.6 months (95%CI: 5.1-8.1) vs 6.9 months (95%CI: 5.3-8.5) in local vs referred patients, respectively (Figure 2). The two-year cumulative incidence of NRM was 26% (95%CI: 19%-33%) in local vs 20% (95%CI: 13%-27%) in referred patients (Figure 2). Univariate Cox regression analysis did not reveal the patient site of diagnosis and treatment (local vs referred) associated with OS (Table 2).

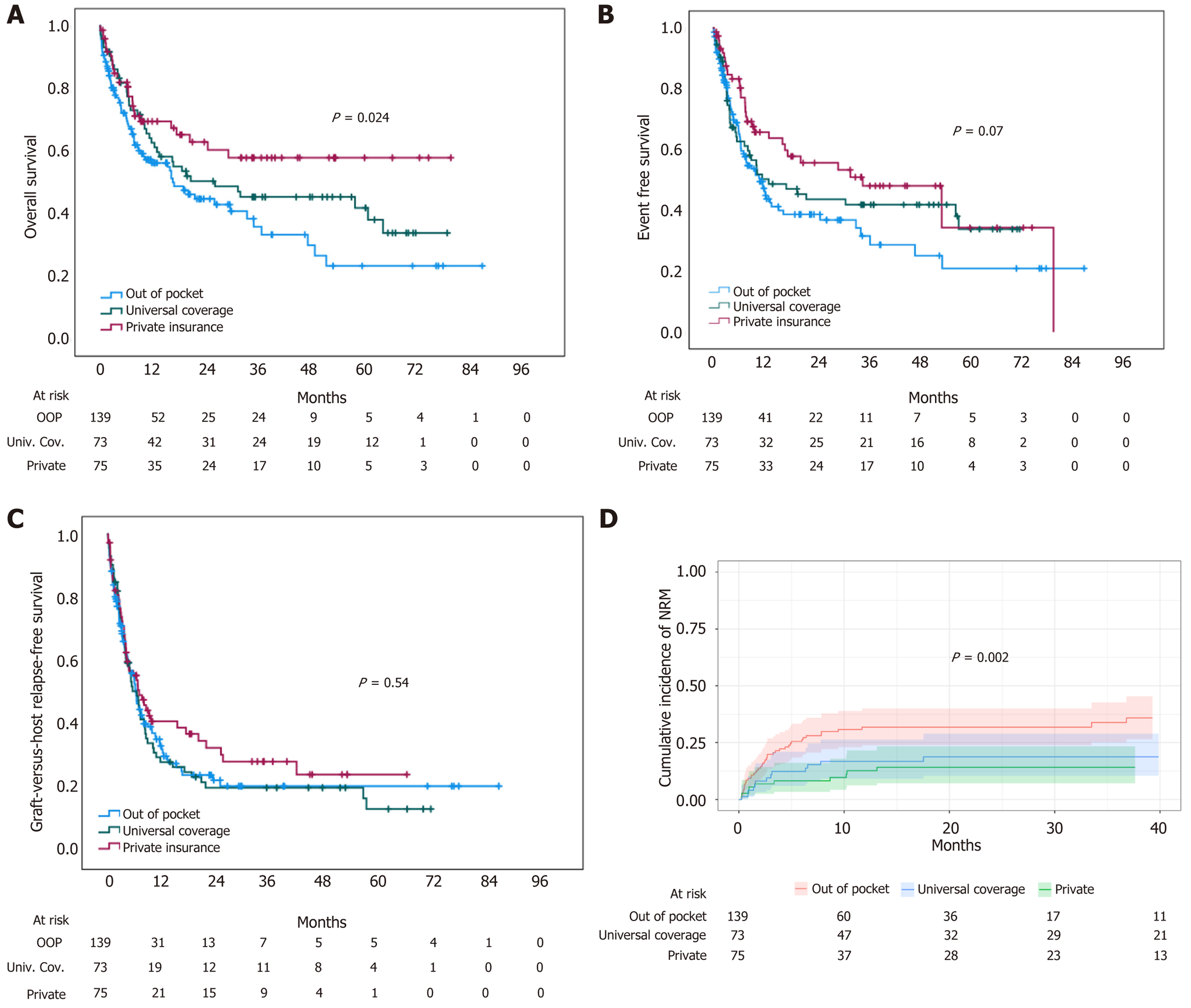

Patients treated in the federal government coverage program were younger and received more frequent myeloablative conditioning regimens with calcineurin inhibitor and methotrexate GVHD prophylaxis than the private insurance and OOP groups (Table 3). Patients who had private insurance experienced the best outcomes with a median OS not reached, while OOP patients did worse with a median OS of 16.9 months (95%CI: 11.2-22.7). Patients in the universal coverage program had a median OS of 26.3 months (95%CI: NC-63.5) (P = 0.024) (Figure 3). Median EFS was not statistically different, with 35.1 months (95%CI: 4-66.1), 13.1 months (95%CI: 1.1-25), and 11 months (95%CI: 7.1-14.9) in private, universal coverage, and OOP patients, respectively (P = 0.07). Similarly, GRFS was 7.1 months (95%CI: 4.1-10.2), 6.6 months (95%CI: 4.6-8.7), and 6.5 months (95%CI: 5.3-7.7) in private, universal coverage, and OOP patients, respectively (P = 0.54). In the univariate and multivariate analysis payment coverage was associated with OS, with access to private healthcare-associated to better survival. In the multivariate analysis, besides DRI, payment coverage was the only variable associated with overall survival (Table 2).

| Variable | OOP | Universal | Private | P value | ||||

| n = 139 | 100% | n = 73 | 100% | n = 75 | 100% | |||

| Sex | Male | 81 | 58.3 | 41 | 56.2 | 46 | 61.3 | 0.81 |

| Female | 58 | 41.7 | 32 | 43.8 | 29 | 38.7 | ||

| Age | Median (years) | 35 | (15-80) | 29 | (16-65) | 43 | (15-67) | < 0.001 |

| Diagnosis | AML | 37 | 26.6 | 15 | 20.5 | 25 | 33.3 | 0.03 |

| ALL | 39 | 28.1 | 25 | 34.2 | 12 | 16 | ||

| AA | 20 | 14.4 | 10 | 13.7 | 6 | 8 | ||

| NHL | 8 | 5.8 | 10 | 13.7 | 11 | 14.7 | ||

| MDN | 10 | 7.2 | 4 | 5.5 | 11 | 14.7 | ||

| HL | 9 | 6.5 | 4 | 5.5 | 4 | 5.3 | ||

| CML | 7 | 5 | 3 | 4.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| CMML | 3 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.7 | ||

| PMF | 3 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| CLL | 3 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| MM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Residence | In state | 46 | 33.1 | 41 | 56.2 | 36 | 48 | 0.003 |

| Out of state | 93 | 66.1 | 32 | 43.8 | 39 | 52 | ||

| Institution | Local | 38 | 27.3 | 45 | 61.6 | 39 | 52 | |

| Referral | 101 | 72.7 | 28 | 38.4 | 36 | 48 | < 0.001 | |

| Donor | Identical | 51 | 36.7 | 29 | 39.7 | 31 | 41.3 | 0.78 |

| Haploidentical | 88 | 63.3 | 44 | 60.3 | 44 | 58.7 | ||

| Treatment lines | Median | 2 | (0-6) | 2 | (0-5) | 1 | (0-5) | 0.62 |

| DRI | Non-malignant | 20 | 14.4 | 10 | 13.7 | 6 | 8 | 0.22 |

| Low | 3 | 2.2 | 3 | 4.1 | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| Intermediate | 56 | 40.3 | 36 | 49.3 | 25 | 33.3 | ||

| High | 47 | 33.8 | 18 | 24.7 | 35 | 46.7 | ||

| Very high | 13 | 9.4 | 6 | 8.2 | 8 | 10.7 | ||

| HCT-CI | Median | 0 | (0-4) | 0 | (0-2) | 1 | (0-5) | 0.08 |

| Conditioning | MAC | 57 | 41 | 51 | 69.8 | 35 | 46.7 | 0.001 |

| RIC | 62 | 44.6 | 14 | 19.2 | 32 | 42.7 | ||

| NMA | 20 | 14.4 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 10.7 | ||

| CD34 | Median | 9 | (1-16) | 9 | (2.4-19) | 8 | (1.8-23.7) | 0.95 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | PTCy | 109 | 78.4 | 48 | 65.8 | 63 | 84 | 0.03 |

| CNI + MTX | 30 | 21.6 | 25 | 34.2 | 12 | 16 | ||

| Recovery | ANC | 15 | (10-24) | 14 | (10-22) | 15 | (10-48) | 0.66 |

| Platelet | 15 | (10-100) | 14.5 | (10-24) | 15 | (10-44) | 0.83 | |

| Graft failure | 17 | 13.1 | 13 | 18.3 | 8 | 12.2 | 0.5 | |

| aGVHD | Grades 1-2 | 46 | 37.1 | 23 | 38.3 | 23 | 31.9 | 0.7 |

| Grades 3-4 | 14 | 11.3 | 8 | 13.3 | 6 | 8.3 | ||

| cGVHD | Mild | 14 | 14.9 | 11 | 19.6 | 15 | 23.8 | 0.09 |

| Moderate | 13 | 13.8 | 13 | 23.2 | 13 | 20.6 | ||

| Severe | 3 | 3.2 | 6 | 10.7 | 5 | 7.9 | ||

| Early mortality | 30 d | 13 | 9.4 | 5 | 6.8 | 3 | 4 | 0.35 |

| 60 d | 24 | 17.3 | 7 | 9.6 | 6 | 8 | 0.12 | |

Our analysis revealed a significant outcome contrast between patients with private insurance and those who paid OOP. Access to comprehensive insurance coverage may have a substantial positive impact on the post-alloHSCT journey. Patients who depend on OOP payments experienced the poorest outcomes. This finding emphasizes the critical role of financial barriers and highlights the challenges faced by individuals who lack adequate healthcare coverage. Interestingly, our analysis did not detect significant differences in outcomes between patients residing locally and those from out-of-state nor between patients referred from another institution and those with a local diagnosis. These findings suggest that geographical factors and referral sources are not significant determinants of outcomes in our population. We observed an increased rate of severe cGVHD in patients living in-state vs those living out of state (12.2 vs 2.4%). This finding may be explained by the fact that out-of-state patients received PTCy as GVHD prophylaxis more frequently. Similarly, patients diagnosed and treated locally had increased rates of grade III-IV aGVHD (16.4 vs 6.8%), but the reasons are unclear as GVHD prophylaxis strategies were similar between groups.

In our multivariate analysis, payment coverage emerged as a relevant factor associated with overall survival. Patients paying OOP exhibited an increased risk of mortality compared to those with private insurance. The association between payment coverage and OS highlights the significant role of insurance status in determining outcomes after alloHSCT. Several studies previously emphasized the economic burden of an alloHSCT. Over 40% of patients report selling or withdrawing money from accounts despite insurance coverage[13-15]. Fu et al[2] analyzed the long-term outcomes of patients who underwent alloHSCT for malignant and benign hematological disorders and had at least 1 year of remission. The authors reported that patients with a lower socioeconomic status (annual household income < $51000/year) have a higher risk of all-cause mortality and NRM. Hamilton et al[3] analyzed the impact of several SDH on chronic GVHD health outcomes, reporting that higher income, the ability to work, and having a partner were all associated with better chronic GVHD symptom scores (Lee score), although not survival. Higher income, the ability to work, and level of education were also associated with better quality of life and activity levels. As reported by Hong et al[4], patients with worse community health status, determined by several sociodemographic, environmental, and community indicators, have inferior survival after alloHSCT due to an increase in NRM. While we did not observe a significant difference in early mortality, we did observe an increase in NRM in OOP patients (Figure 3). Relevant transplant complications can generate additional expenses, increasing costs affecting patients who had an OOP payment, including conditioning regimen toxicities, GVHD, and bacterial and viral infections, which result in frequent consults and testing, hospital admissions, and the use of expensive drugs, which may be inaccessible and impact outcomes. Similarly, disease relapse or progression also requires significant use of resources, which may be limited for patients covering costs OOP and result in worse outcomes, as shown by the continuing separation of OS curves beyond the 12-month timepoint. This finding emphasizes the need for policy efforts to improve access to insurance coverage for alloHSCT patients, not only to access the procedure but throughout their entire journey, particularly in regions where financial barriers to care are prevalent.

To our knowledge, this analysis is the first to compare payment sources with outcomes in the Mexican population. A prior study assessed outcomes with regard to socioeconomic status, finding no difference between patient groups when social support is provided[16]. These results correlate with our findings since patients who had financial support during the times of the federal program had better outcomes than those who did not, demonstrating the positive effect of universal coverage for HSCT. Our findings have relevant implications for healthcare policymakers and practitioners. They may lead physicians to identify individuals facing economic and social marginalization and implement targeted interventions and organizations to advocate for the permanent inclusion of HSCT in government-funded programs, limiting the need for OOP coverage and avoiding financial toxicity.

Similarly, a study by Yanez et al[17] found that economic barriers were a main concern for the Latino population in the United States, a reflection of their counterparts in Latin America as they were overrepresented in low-income brackets and less likely to have health insurance coverage. Thus, addressing disparities in outcomes associated with payment coverage and healthcare access is fundamental. Developing intervention strategies to reduce economic inequity should be a priority everywhere, especially for underserved populations and those living in low- and middle-income countries. Initiatives that expand healthcare coverage and reduce financial barriers may improve survival rates and overall outcomes for alloHSCT patients. Our results emphasize the importance of ongoing efforts to study and address social determinants of health in healthcare delivery, particularly in regions where disparities may be more pronounced.

Certain limitations in our study need to be acknowledged. Our population may not represent all alloHSCT patients since it is based in a single region. Both transplant centers are high-volume reference centers that may not reflect the reality of the rest of the country. Access to private healthcare is also a surrogate for better social determinants of health in areas that may impact outcomes after alloHSCT, such as income, housing, education, nutrition, transportation, and a robust social support network, among others. The study is also limited by its retrospective nature and the lack of assessment of patient-level socioeconomic indices, as both institutions have distinct procedures that are not directly comparable. Future research is needed to understand better how social determinants of health interact with outcomes after alloHSCT.

The site of residence or referral for HSCT did not impact outcomes. However, access to private insurance coverage for alloHSCT was associated with improved OS and reduced NRM compared to patients forced to cover expenses OOP or through government-funded programs.

Despite the World Health Organization's recognition of the significance of non-medical factors in health outcomes, existing data primarily originates from high-income countries, leaving a lack of insight into Latin American specifics. The study aims to explore the association between social determinants—specifically, the source of transplant payment, site of referral, and place of residence—and overall survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT) in Mexico.

The motivation for this study lies in recognizing the potential impact of social determinants of health on alloHSCT outcomes, and the unique challenges faced by patients in Mexico.

To examine the association between the source of transplant payment, site of referral, and place of residence on overall survival after alloHSCT in Mexico. To compare outcomes based on payment source (out-of-pocket, private insurance, and government-funded programs), place of residence (in-state vs out-of-state), and referral source (local diagnosis and treatment vs referred from another institution). To analyze the impact of social determinants, particularly financial barriers, on early mortality, event-free survival, graft-versus-host-relapse free survival, and non-relapse mortality after alloHSCT.

Adopting a retrospective cohort design, this study includes patients from two major alloHSCT centers in Mexico, covering the period from 2015 to 2022. Statistical methods such as chi-square tests, t-tests, Kaplan Meier method, and Cox proportional hazard regression modeling were employed to analyze patient demographics, diagnostic characteristics, transplant procedures, and outcomes.

The study found that the site of residence or referral for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) did not significantly affect outcomes. However, access to private insurance coverage for allogeneic HSCT was associated with improved overall survival (OS) and reduced non-relapse mortality (NRM) when compared to patients covering expenses out-of-pocket or through government-funded programs.

The study proposes that in allogeneic transplant recipients in low- and middle-income countries, the impact of social determinants of health, specifically the place of residence and transplant cost coverage, influences outcomes after hematopoietic cell transplantation. It suggests that access to healthcare coverage is associated with improved OS and reduced NRM.

Future research in this field should focus on developing strategies to intervene and reduce economic barriers. Ongoing studies should continue to explore the broader impact of social determinants of health on healthcare delivery, especially in regions where disparities may be heightened.

The authors would like to thank Sergio Lozano-Rodriguez, MD, for his review of the manuscript.

| 1. | World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health. |

| 2. | Fu S, Rybicki L, Abounader D, Andresen S, Bolwell BJ, Dean R, Gerds A, Hamilton BK, Hanna R, Hill BT, Jagadeesh D, Kalaycio ME, Liu HD, Pohlman B, Sobecks RM, Majhail NS. Association of socioeconomic status with long-term outcomes in 1-year survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1326-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hamilton BK, Rybicki L, Arai S, Arora M, Cutler CS, Flowers MED, Jagasia M, Martin PJ, Palmer J, Pidala J, Majhail NS, Lee SJ, Khera N. Association of Socioeconomic Status with Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Outcomes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:393-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hong S, Brazauskas R, Hebert KM, Ganguly S, Abdel-Azim H, Diaz MA, Beattie S, Ciurea SO, Szwajcer D, Badawy SM, Gratwohl AA, LeMaistre C, Aljurf MDSM, Olsson RF, Bhatt NS, Farhadfar N, Yared JA, Yoshimi A, Seo S, Gergis U, Beitinjaneh AM, Sharma A, Lazarus H, Law J, Ulrickson M, Hashem H, Schoemans H, Cerny J, Rizzieri D, Savani BN, Kamble RT, Shaw BE, Khera N, Wood WA, Hashmi S, Hahn T, Lee SJ, Rizzo JD, Majhail NS, Saber W. Community health status and outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States. Cancer. 2021;127:609-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | González Block MÁ, Reyes Morales H, Hurtado LC, Balandrán A, Méndez E. Mexico: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit. 2020;22:1-222. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Rivera-Franco MM, Leon-Rodriguez E, Castro-Saldaña HL. Costs of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a developing country. Int J Hematol. 2017;106:573-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gómez-Almaguer D, Gómez-De León A, Colunga-Pedraza PR, Cantú-Rodríguez OG, Gutierrez-Aguirre CH, Ruíz-Arguelles G. Outpatient allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a review. Ther Adv Hematol. 2022;13:20406207221080739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim HT, Logan B, Weisdorf DJ. Novel Composite Endpoints after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021;27:650-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, Storer B. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912-2919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1907] [Cited by in RCA: 2432] [Article Influence: 115.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Armand P, Gibson CJ, Cutler C, Ho VT, Koreth J, Alyea EP, Ritz J, Sorror ML, Lee SJ, Deeg HJ, Storer BE, Appelbaum FR, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ, Kim HT. A disease risk index for patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;120:905-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Giralt S, Lazarus H, Ho V, Apperley J, Slavin S, Pasquini M, Sandmaier BM, Barrett J, Blaise D, Lowski R, Horowitz M. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1628-1633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1270] [Cited by in RCA: 1505] [Article Influence: 88.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Kumar A, Ayala E, Aljurf M, Nishihori T, Marsh R, Burroughs LM, Majhail N, Al-Homsi AS, Al-Kadhimi ZS, Bar M, Bertaina A, Boelens JJ, Champlin R, Chaudhury S, DeFilipp Z, Dholaria B, El-Jawahri A, Fanning S, Fraint E, Gergis U, Giralt S, Hamilton BK, Hashmi SK, Horn B, Inamoto Y, Jacobsohn DA, Jain T, Johnston L, Kanate AS, Kansagra A, Kassim A, Kean LS, Kitko CL, Knight-Perry J, Kurtzberg J, Liu H, MacMillan ML, Mahmoudjafari Z, Mielcarek M, Mohty M, Nagler A, Nemecek E, Olson TS, Oran B, Perales MA, Prockop SE, Pulsipher MA, Pusic I, Riches ML, Rodriguez C, Romee R, Rondon G, Saad A, Shah N, Shaw PJ, Shenoy S, Sierra J, Talano J, Verneris MR, Veys P, Wagner JE, Savani BN, Hamadani M, Carpenter PA. Standardizing Definitions of Hematopoietic Recovery, Graft Rejection, Graft Failure, Poor Graft Function, and Donor Chimerism in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Report on Behalf of the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021;27:642-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Khera N, Chang YH, Hashmi S, Slack J, Beebe T, Roy V, Noel P, Fauble V, Sproat L, Tilburt J, Leis JF, Mikhael J. Financial burden in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:1375-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Hahn T, Lee SJ, McCarthy PL, Ammi M, Denzen E, Drexler R, Flesch S, James H, Omondi N, Pedersen TL, Murphy E, Pederson K. Pilot study of patient and caregiver out-of-pocket costs of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:865-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Maziarz RT, Hao Y, Guerin A, Gauthier G, Gauthier-Loiselle M, Thomas SK, Eldjerou L. Economic burden following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:1133-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Leon Rodriguez E, Rivera Franco MM, Ruiz González MC. Association of Outcomes and Socioeconomic Status in Mexican Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:2098-2102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yanez B, Taub CJ, Waltz M, Diaz A, Buitrago D, Bovbjerg K, Chicaiza A, Thompson R, Rowley S, Moreira J, Graves KD, Rini C. Stem Cell Transplant Experiences Among Hispanic/Latinx Patients: A Qualitative Analysis. Int J Behav Med. 2023;30:628-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0