Published online Jan 19, 2026. doi: 10.5497/wjp.v15.i1.113080

Revised: September 5, 2025

Accepted: December 17, 2025

Published online: January 19, 2026

Processing time: 154 Days and 5.2 Hours

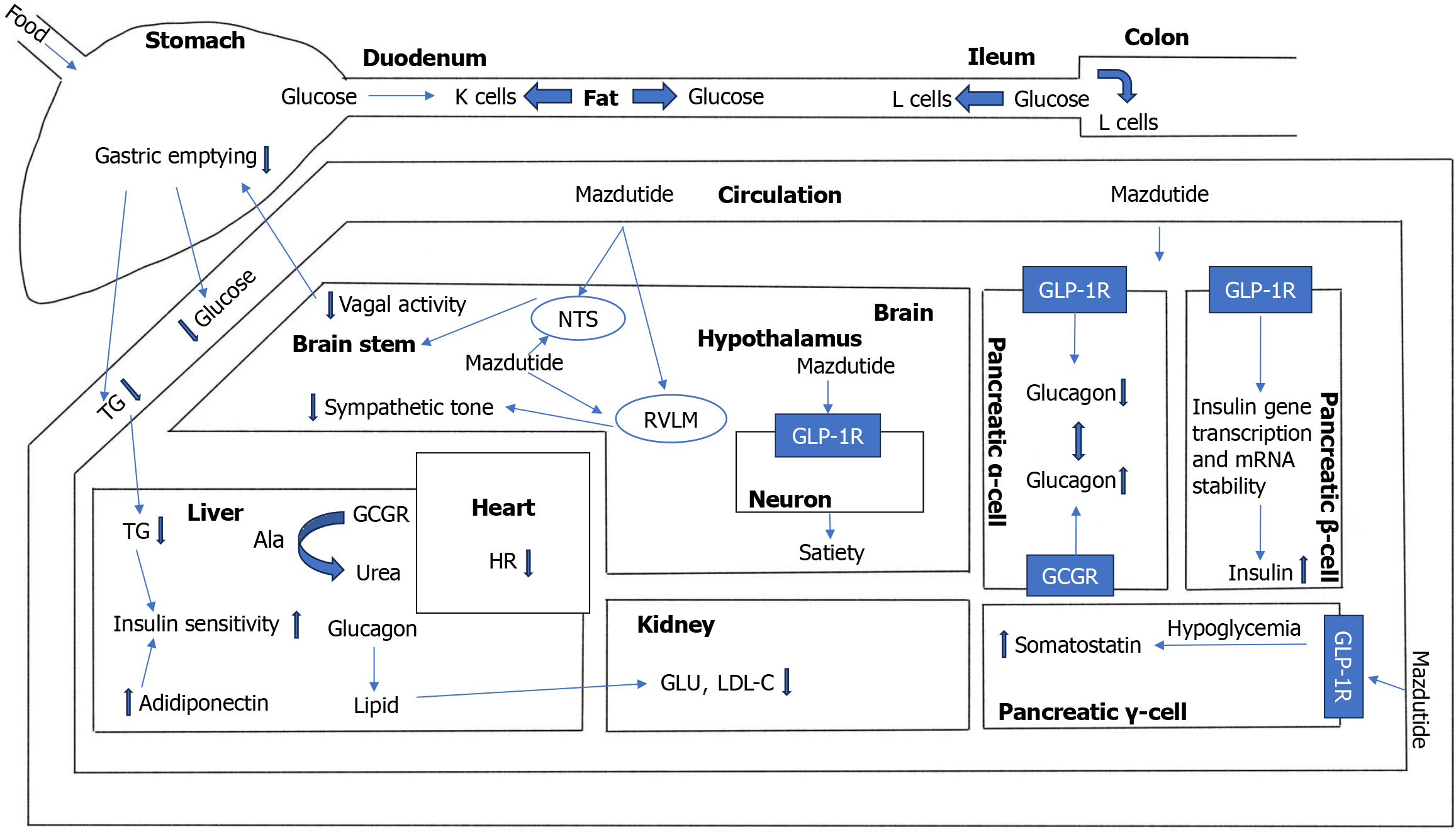

Obesity has emerged as a global health crisis, necessitating effective therapeutic options. The “GLORY-1” study evaluated the efficacy and safety of mazdutide, a dual receptor agonist targeting glucagon (GCG) and GCG-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). As the first GLP-1/GCG dual-receptor agonist to successfully complete phase 3 trials, this drug marks a significant advancement in innovative drug discovery for endocrine and metabolic diseases in China. Unlike conventional GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) single-target drugs, mazdutide activates both GCG receptor (GCGR) and GLP-1R simultaneously, enhancing fat oxidation and offering substantial benefits for weight reduction and comprehensive metabolic regulation. In terms of safety, mazdutide exhibits an overall safety profile comparable to existing GLP-1R agonists, with adverse events primarily involving mild to moderate gas

Core Tip: Mazdutide has breakthrough value in terms of weight loss and metabolic regulation. Future research needs to further investigate its specific mechanisms to promote clinical translation.

- Citation: Deng CX, Chen ZM, Tang YX, Xi ZX, Wang SY, Wu HY, Xu B, Xu TC. Mazdutide: An emerging glucagon/GCG-like peptide-1 dual receptor agonist for obesity—a comparison of therapeutic effects and potential side effects with GCG-like peptide-1 inhibitors. World J Pharmacol 2026; 15(1): 113080

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3192/full/v15/i1/113080.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5497/wjp.v15.i1.113080

In the 21st century, obesity has emerged as a worldwide epidemic, posing a significant health challenge to a growing portion of the population. This stems not only from its link to body image anxiety, discrimination, and various social issues, but also from its capacity to impose heavy physiological burdens and precipitate other serious illnesses[1]. Research indicates that individuals with obesity have a 57% likelihood of developing diabetes, 17% for hypertension, 30% for cholecystitis, and 14% for osteoarticular disorders, with these risks rising in tandem with further weight gain[2]. According to the 2023 report by the World Health Organization, the number of obese people worldwide has nearly tripled over the past three decades. By 2022, the global overweight and obese population had reached approximately 2 billion and 650 million, respectively, and it is estimated that by 2035, more than 4 billion people will be overweight or obese[3].

As the world’s most populous country, China exhibits obesity characteristics that differ markedly from global patterns. Although the average body mass index (BMI) among the Chinese population is lower than that in Europe and North America, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome is notably higher—approximately 40% of overweight individuals have visceral fat accumulation–dominant “hidden obesity”[4], most commonly accompanied by metabolic dysfunct

Presently, the main strategies for managing obesity emphasize a healthy, low-calorie diet, enhanced physical activity, and effective execution of intervention plans. According to Chinese obesity management guidelines, if lifestyle interventions cannot achieve adequate weight control, pharmacotherapy should be promptly initiated. Existing pharmacological agents for weight loss primarily include benaglutide, liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide[6], which achieve weight re

Glucagon (GCG)-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists, potent pharmacological agents for weight reduction, exert their effects by regulating intestinal hormone levels, thereby influencing body weight and metabolic processes[7,8]. It is worth noting that within the domain of GLP-1R targeted drugs, although the weight-reducing efficacy of GLP-1R ag

Oxyntomodulin, an intrinsic cleavage derivative of proglucagon, has the ability to co-activate both GLP-1R and the glucagon receptor (GCGR)[10]. Mazdutide (IBI362 or LY3305677), structurally modeled on mammalian oxyntomodulin, has demonstrated clinical efficacy in weight reduction that surpasses that of existing agents such as semaglutide and may even approximate the outcomes of bariatric surgery. As an emerging obesity treatment, mazdutide offers distinctive therapeutic potential and long-term safety advantages, yet the adverse effect profile of this dual agonist remains insufficiently characterized, creating obstacles to its widespread clinical use[11,12].

In this review, we systematically examine the mechanisms of weight reduction and adverse events associated with mazdutide, contrasting them with those of current GLP-1R single-target drugs, to inform clinical decision-making and promote continued progress in this area.

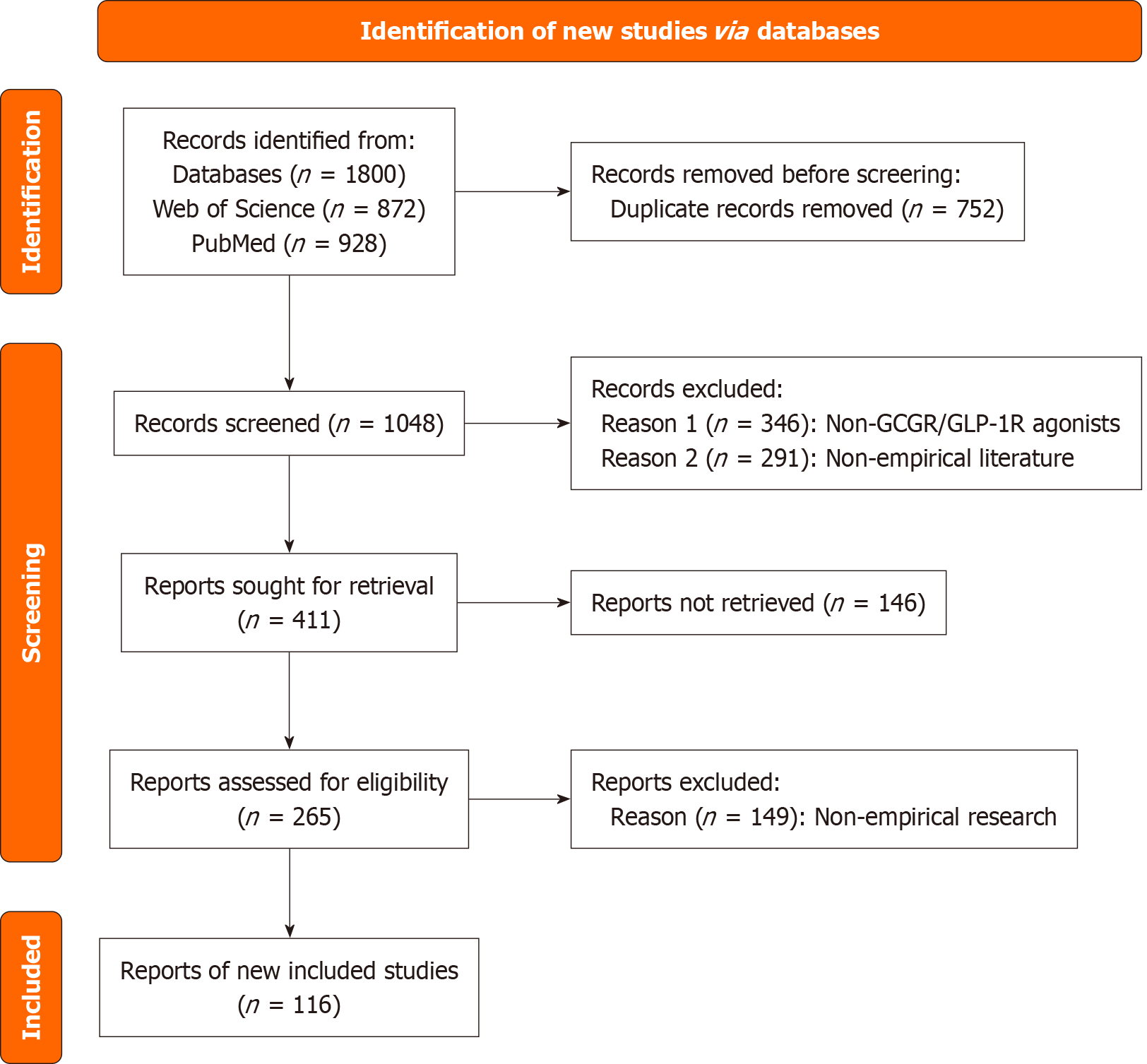

The electronic literature was searched in international electronic databases including PubMed and Web of Science, from their inception to August 2025. The search employed a combination of core terms and free words, including: (“ma

The identification of GLP-1 was facilitated by the development of recombinant DNA technology in the early 1970s. This technological advance enabled the decoding of nucleotide sequences from cloned cDNA corresponding to messenger RNA, which in turn allowed researchers to predict the amino acid sequences of proteins. In the early 1980s, scientists discovered two GCG-related peptides, GLP-1 and GCG-like peptide-2 (GLP-2), within the proglucagon sequences in a variety of species, including rats, hamsters, cows, and humans. The fact that the GLP-1 amino acid sequences are identical across these four mammalian species suggests that GLP-1 plays a vital and evolutionarily conserved role in biological processes.

The discovery of GCG followed the identification of insulin by Banting et al[13] in 1921, who noted that pancreatic extracts and crude insulin preparations caused transient hyperglycemic episodes before blood glucose levels returned to normal. Subsequent studies led to the isolation of a pancreatic substance that raised blood glucose in rabbits and dogs, counteracting insulin's glucose-lowering effects. This substance was named “GCG”[14].

Molecular physiology of GLP-1: The signal transduction of GLP-1 primarily depends on the cyclic adenosine mo

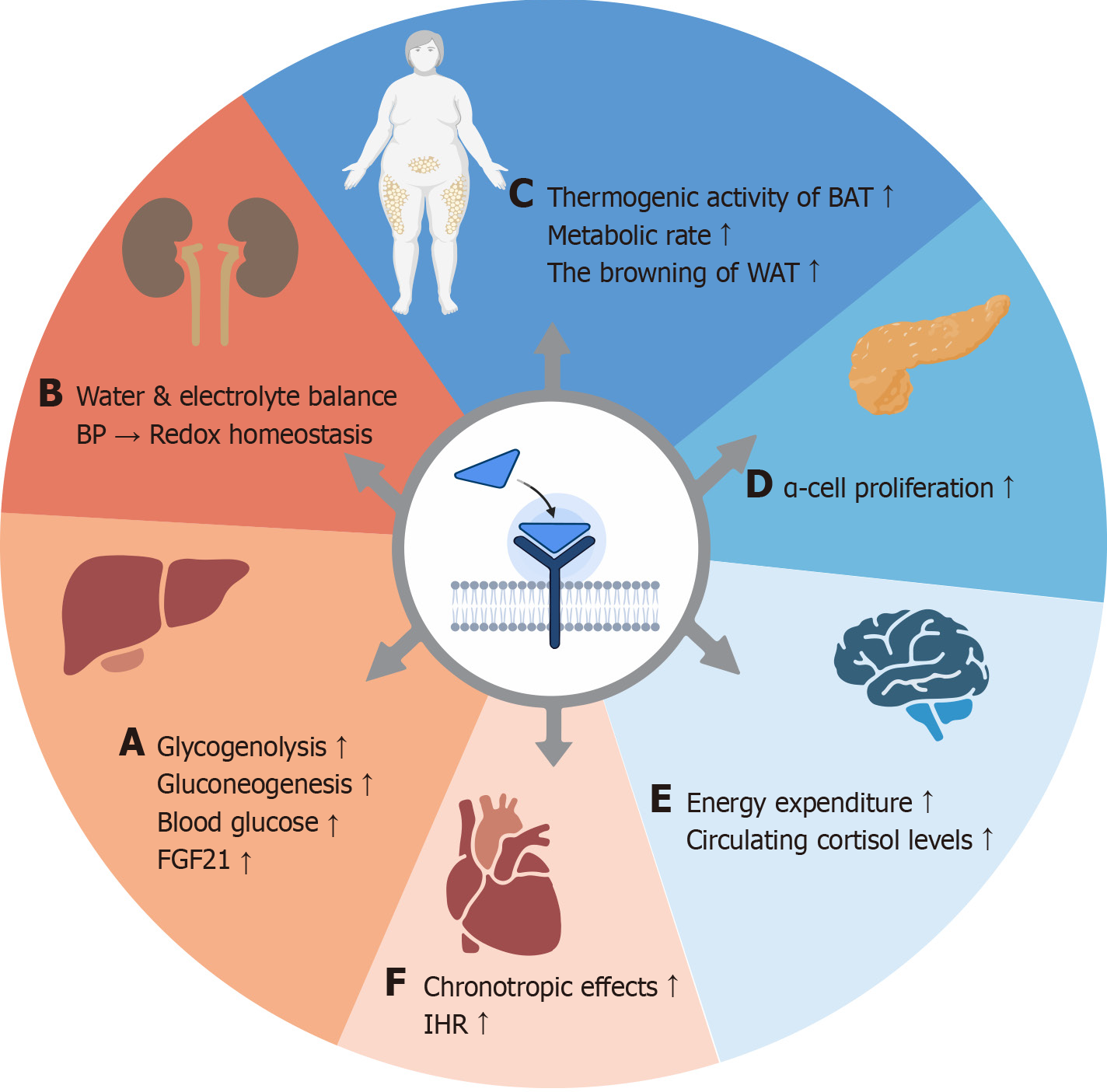

Molecular physiology of GCG: GCG is a 29-amino-acid peptide hormone secreted by pancreatic α-cells and serves as a key regulator of hepatic glucose production, functioning in tandem with insulin. In contrast to the larger volume of insulin secreted by pancreatic β-cells, the secretion of GCG is relatively low. GCG acts through its receptor, GCGR, a G protein-coupled receptor primarily found in pancreatic β-cells and hepatocytes. Upon binding to GCG, GCGR stimulates hepatic glycogenolysis and elevates blood glucose levels[20]. Its tissue distribution is extensive, including the liver, kidneys (primarily in nephrons, renal tubules, and collecting ducts, especially distal tubules), pancreas (α, β, δ cells), intestinal smooth muscle, brain, adipose tissue, heart, and preadipocytes, among others[21].

The activation mechanism of GCGR involves triggering the cAMP/PKA/p-Creb signaling pathway upon binding to GCG. It mainly activates Gαs protein, stimulates adenylate cyclase to generate cAMP, and thereby activates PKA. In addition, it can activate phospholipase C through Gq protein, producing inositol trisphosphate and calcium ion (Ca2+) signals that participate in downstream regulation[22]. The regulatory mechanisms of GCG vary across different organs: (1) In the liver, activation of GCGR stimulates glycogen phosphorylase kinase and upregulates key enzymes such as phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose-6-phosphatase, thereby promoting glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, which increases blood glucose levels. Research by Nason et al[23] has shown that hepatic GCGR signaling enhances circulating levels of fibroblast growth factor 21, which is a regulatory factor for the weight-loss effect of GCG and plays an important role in energy homeostasis. A review by Kleinert et al[24] specifically highlights the catabolic effects of GCG and the subsequent anabolic counter-regulatory responses aimed at restoring metabolite levels, which may result in a “futile cycle” that increases energy expenditure; (2) In the kidneys, GCGR plays a vital role in maintaining water and electrolyte balance, regulating blood pressure, and preserving redox homeostasis. Dysfunction in GCGR may contribute to the development and progression of chronic kidney disease by inducing insulin resistance and lowering the glomerular filtration rate, among other mechanisms[25,26]; (3) In the central nervous system, GCGR signaling can be transmitted to the hypothalamus via hepatic vagal afferents, directly influencing GCGR within the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. GCG promotes satiety and enhances energy expenditure in both rodents and humans through the liver-vagus nerve-hypothalamus axis. Additionally, GCG increases circulating cortisol levels in humans and exerts effects on the sympathetic nervous system via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, thereby influencing energy expenditure[27]. A review by Müller et al[22] notes that GCG can cross the blood-brain barrier, with its immunoreactivity detected in several brain regions associated with metabolic regulation, including the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala. Furthermore, GCGR is expressed in the anterior pituitary, and GCG may be associated with pituitary secretion of ar

GCG and GLP-1 are both derived from the same biosynthetic precursor, proglucagon, and play key roles in regulating lipid and bile acid metabolism. Previous studies have established the structural basis of GCGR and GLP-1R, comprising both shared and peptide-specific structural features. Moreover, the N-terminal and central regions of the peptides exhibit pronounced conformational flexibility, allowing dual agonism when appropriate amino acids are incorporated at these positions[33]. Notably, GCG itself is a dual agonist capable of activating both GLP-1R and GCGR, but with up to 100-fold higher selectivity for GCGR[34]. This suggests that dual agonists should possess comparable activity at both receptors, or potentially greater selectivity for GLP-1R. Because GCG and GLP-1 exert opposite effects on glycemic regulation, com

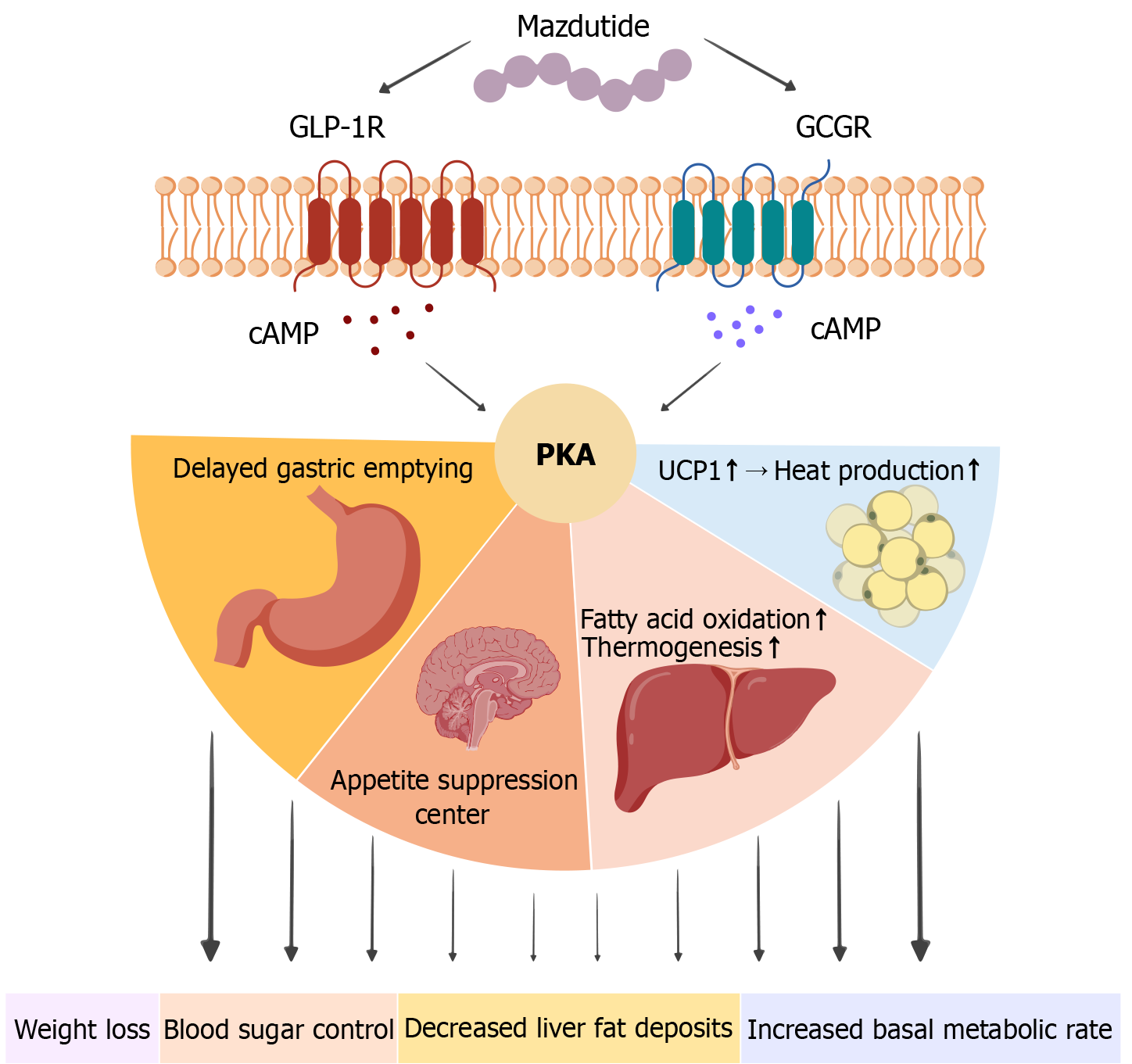

Mazdutide is a novel peptide-based metabolic modulator, structurally derived from the GLP-1 scaffold and modified by lipidation to extend its plasma half-life, thereby enabling a once-weekly subcutaneous dosing regimen[35]. Mazdutide integrates functional domains that activate both GLP-1R and GCGR, conferring multiple pharmacological activities including appetite suppression, glycemic control, and enhanced energy expenditure[36].

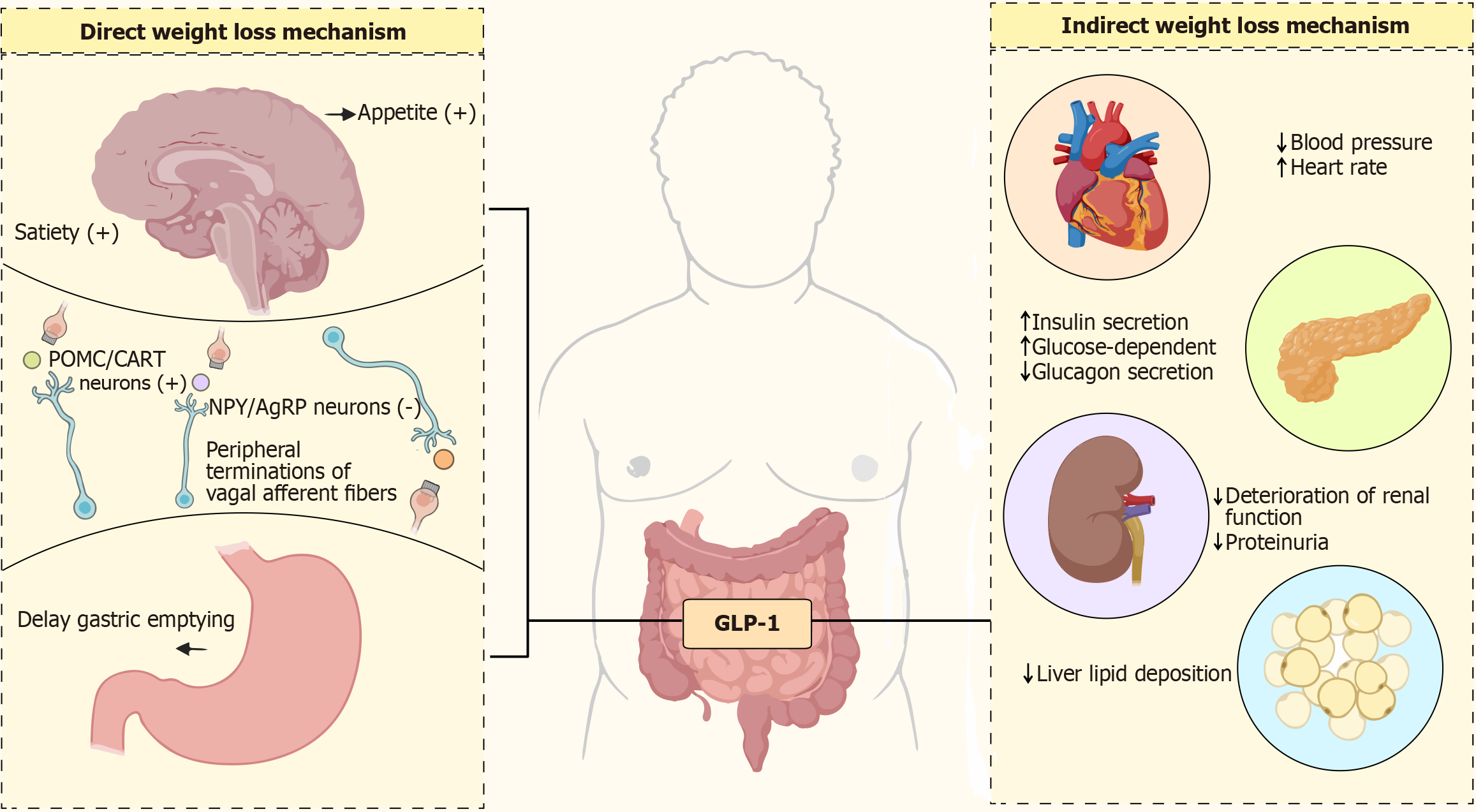

GLP-1R agonists are now widely used in the treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), with classical mechanisms including: Activation of hypothalamic GLP-1R in the central nervous system to suppress appetite center activity and delay gastric emptying, thereby reducing energy intake, and, in peripheral tissues, enhancement of pan

Exendin is a functional mimetic of GLP-1, while its variant exendin (9-39) lacks the N-terminal segment required for receptor activation and internalization, thereby functioning as a GLP-1R inhibitor. As a classical inhibitor, exendin (9-39) does not induce rapid receptor activation or internalization and is widely used in animal studies for mechanistic investigations. Studies have shown that blocking GLP-1 signaling markedly reduces insulin secretion, diminishes appetite suppression, and attenuates metabolic improvement, further confirming the central role of the GLP-1 pathway in metabolic interventions. In terms of secretion mechanisms, GLP-1 release is finely regulated by multiple ion channels and signaling pathways. Existing studies have demonstrated that the synergistic interaction between intestinal TRPV4 channels and the sodium–calcium exchanger NCX1 can trigger glucose-dependent GLP-1 secretion via the Ca2+/PKCα signaling axis. This mechanism not only aids in understanding the dynamic release process of GLP-1 but also provides a theoretical basis for developing novel targets to regulate its secretion. However, it is important to note that non-specific modulation of calcium channels may pose risks such as hypoglycemia. Thus, GLP-1 signaling interventions must balance metabolic benefits against potential side effects, offering a key direction for GLP-1R inhibitor development.

The core innovation of mazdutide lies in its dual activation of both GLP-1R and GCGR, establishing a "dual-pathway" model of metabolic modulation. Through the GLP-1R pathway, mazdutide exerts effects akin to GLP-1R agonists, promoting glucose homeostasis. Additionally, the activation of GCGR provides a distinct advantage in metabolic regulation. GCGR is abundantly expressed in the liver and other tissues, and mazdutide stimulates the hepatic cAMP-PKA signaling pathway, which enhances fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial thermogenesis, leading to an increase in basal metabolic rate and significant elevation in energy expenditure[40]. This action offsets the limitation of the GLP-1 pathway in suppressing energy intake, enabling a bidirectional regulation of both energy intake (via central appetite suppression and delayed gastric emptying) and energy expenditure. Based on these mechanisms, the "dual metabolic engine" theory has been proposed, suggesting that mazdutide facilitates weight loss by concurrently regulating intake and expenditure. This dual action may offer superior synergistic effects compared to GLP-1R single-target therapies[41].

It is worth noting that, beyond stimulating lipid metabolism and energy use, GCGR activation in the liver can increase gluconeogenesis, potentially diminishing the net glucose-lowering capacity of mazdutide[42]. Nonetheless, evidence from clinical and preclinical studies indicates no substantial hyperglycemia risk with mazdutide, implying that GLP-1–driven increases in insulin release and reductions in GCG secretion may dynamically counterbalance gluconeogenesis. Additionally, concurrent GLP-1R and GCGR activation can avert hyperglycemia caused by GCGR stimulation. Maz

The GLP-1/GCG dual-receptor agonists offer innovative approaches for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders. BI 456906 has demonstrated promising results in preclinical and clinical studies, with its dual receptor agonism shown to synergistically enhance anti-obesity efficacy. Zimmermann et al[43] provided a comprehensive pharmacological profile, confirming its potential as a therapeutic agent for metabolic diseases. Additionally, Yazawa et al[44] confirmed the agent's safety and efficacy in a Japanese cohort, noting significant body weight reduction and improved metabolic parameters. As ongoing research continues to elucidate its pharmacological mechanisms, BI 456906 is poised to become a key player in the management of obesity and related metabolic conditions[45,46]. Similarly, Cotadutide, by targeting both the GLP-1R and GCGR, promotes glycemic control, weight loss, and liver health. Studies have demonstrated Co

| Characteristic | Cotadutide | BI 456906 | Mazdutide |

| Mechanism of action | GLP-1R and GCGR dual agonist | GLP-1R and GCGR dual agonist | GLP-1R and GCGR dual agonist (“dual metabolic engine” with appetite suppression + energy expenditure) |

| Primary target indications | Obesity, T2DM | Obesity, T2DM, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | Obesity, T2DM, MAFLD, NASH |

| Pharmacokinetics | Acylated for extended half-life, once-daily subcutaneous dosing | Acylated for extended half-life, once-weekly subcutaneous dosing | Lipidation-modified peptide, once-weekly subcutaneous dosing |

| Body weight reduction | Up to 12.37% placebo-corrected weight loss in clinical trials | Up to 13.8% placebo-corrected weight loss | Up to 14%-15% placebo-corrected (phase 3 GLORY-1 trial, 48 weeks) |

| Dose formulation | Daily subcutaneous injections | Weekly subcutaneous injections | Weekly injections (3-9 mg tested; 6 mg effective) |

| Efficacy on glucose control | Reduces glucose, HbA1c levels with dual receptor activation | Significant reduction in glucose AUC and improvement in oral glucose tolerance | Significant HbA1c reduction (up to -2.2%), enhanced insulin secretion, reduced glucagon |

| Gastric emptying effects | Delayed gastric emptying in the early phase of treatment | Modest effect on gastric emptying, dose-dependent | Delays gastric emptying + appetite suppression (stronger than GLP-1 mono-agonists) |

| Effect on lipid profile | Modest improvements in plasma lipids (cholesterol, triglycerides) | Significant reductions in liver triglycerides and plasma cholesterol | Significant reduction in liver fat (-80% in GLORY-1), lower TG, LDL-C, uric acid |

| Cardiovascular effects | No significant cardiovascular effects noted | Mild increase in pulse rate, no serious cardiovascular effects | Improves cardiac risk factors; transient tachycardia in some patients |

| Target receptor engagement | Balanced GLP-1R and GCGR engagement for weight loss and metabolic control | Balanced GLP-1R and GCGR engagement, more potent on GCGR | Balanced GLP-1R/GCGR; biased agonism favors fat oxidation |

| Clinical trial results | Positive results in T2D patients and obese patients with improved glycemic control | Proven superior weight loss compared to semaglutide in preclinical trials | Phase 3 GLORY-1 (China): -14% weight, 49.5% ≥ 15% weight loss, robust safety profile |

Mazdutide’s dual receptor agonist properties enable it to exert a comprehensive regulatory effect, thereby achieving a more comprehensive therapeutic effect[52,53]. In diet-induced obesity models, it markedly reduces body weight by decreasing fat mass and increasing basal metabolic rate. Intra-islet GCG signaling through β-cell GCGR and GLP-1R restores first-phase glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, while mazdutide enhances insulin gene transcription and mRNA stability[54], improving glycemic control. It also delays gastric emptying more effectively than GLP-1 mono-target agents, suppressing hunger, increasing satiety, and supporting long-term weight management. Jungnik et al[55] found that GCGR in the liver utilizes alanine to synthesize urea and produce glucose, leading to a decrease in plasma alanine concentration. Parker et al[56] used 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy to find that GCGR activity in the liver was positive, confirming the activity characteristics of GCGR in agonists. Therefore, GCGR can stimulate the liver to oxidize fatty acids and reduce fat production, and the combination of these two mechanisms may provide additional hepatoprotective potential for mazdutide. Studies have shown that mazdutide improves hepatic metabolic function, reducing triglycerides, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and serum uric acid levels without elevating transaminases. Given the high prevalence of fatty liver disease and dyslipidemia among obese individuals in China, mazdutide’s significant effect in reducing liver fat accumulation and blood glucose levels has produced excellent results in this population[57]. Both GLP-1R/GCGR dual-target agonists can increase heart rate. The prevailing view is that the primary cause of increased heart rate is the result of drug interactions with the noradrenergic pathway, involving both the central and peripheral systems[58]. Interestingly, despite the increase in heart rate, multiple cardiovascular studies of GLP-1R agonists have shown that they can improve cardiac function and possess certain cardiovascular protective effects. Mazdutide also exhibits this effect. In an obese mouse model, mazdutide improved multiple cardiac metabolic risk factors in a dose-dependent manner, enhanced lipid metabolism markers, reduced waist circumference, blood pressure, and blood lipids, and produced beneficial effects on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. However, it is worth noting that experiments related to the pharmacology of mazdutide were primarily conducted in anesthetized mice rather than awake mice, and it remains unclear whether cardiovascular changes are indirectly influenced by the gastrointestinal tract. GLP-1R are widely distributed in the central nervous system and participate in regulating appetite and satiety[59]. By activating these receptors, mazdutide modulates appetite regulation pathways in the central nervous system, significantly reducing food intake and improving glucose tolerance and insulin secretion[60]. Finally, due to the effects of GLP-1R and GCGR on the kidneys, mazdutide effectively reduces urinary albumin levels. Through its indirect effects on blood glucose, blood pressure, and other parameters, it may exert potential renal protective effects. Overall, mazdutide integrates intake regulation and energy expenditure mechanisms through the synergistic activation of GLP-1R and GCGR, demonstrating clinical potential in weight management and metabolic improvement that surpasses that of GLP-1 monotherapy[61] (Figure 5 and Table 2).

| Therapeutic efficacy | Mazdutide | GLP-1R agonists |

| Appetite suppression | GLP-1R activation → slows gastric emptying and increases satiety, while GCGR activation also suppresses appetite. The dual mechanism enhances the appetite-suppressing effect | GLP-1R activation → same effect, mainly through slowing gastric emptying and increasing satiety to suppress appetite |

| Energy expenditure | GCGR activation → increases basal metabolic rate and energy expenditure, promotes fat oxidation, and aids in weight loss | No such effect; mainly affects energy intake through mechanisms such as slowing gastric emptying, with no direct effect on energy expenditure |

| Liver fat metabolism | GCGR activation → promotes fatty acid oxidation, inhibits lipid synthesis, reduces liver fat accumulation, and improves liver metabolism | Indirect effect (through weight loss), mainly improves liver fat metabolism by reducing body weight, with minimal direct impact on liver fat |

| Glucose metabolism regulation | Dual synergistic effect → reduces hepatic glucose output and increases insulin sensitivity, through activation of GLP-1R and GCGR, jointly regulating glucose metabolism with more pronounced effects | Primarily dependent on insulin secretion promotion, through activation of GLP-1R to promote insulin secretion and inhibit glucagon secretion, thereby regulating blood glucose levels |

Mazdutide, the first dual-target agonist of GLP-1R/GCGR to complete phase 3 trials, has been approved for inclusion in weight management treatments for obese or overweight individuals in China. In phase 1 trials, mazdutide at a dosage of 10 mg was well tolerated, demonstrating a safety profile comparable to that of existing GLP-1 agonists. By week 12, par

| Ref. | Dose (mg) | HbA1c reduction (%) | Weight loss (%) | Achieving HbA1c < 7.0% | Adverse effects |

| Zhang et al[36], 2024 | 3 | -1.41 | -7.1 | 54% | Diarrhea (36%), nausea (23%) |

| 4.5 | -1.35 | -5.3 | 67% | Decreased appetite (29%) | |

| 6 | -1.67 | -7.1 | 73% | Vomiting (14%), hypoglycemia (10%) | |

| Ji et al[62], 2022 | 6, 9 | N/A | 6 mg: -6.1; 9 mg: | N/A | Nausea (23%), diarrhea (36%) (6 mg); nausea (28%), diarrhea (32%) (9 mg) |

| Ji et al[63], 2023 | 3, 4, 6 | N/A | 3 mg: -6.7; 4 mg: | N/A | Diarrhea (36%), nausea (29%), vomiting (14%) (3 mg); diarrhea (38%), nausea (31%), vomiting (16%) (4 mg); diarrhea (36%), nausea (29%), vomiting (14%) (6 mg) |

| Ji et al[42], 2025 | 4, 6 | N/A | 4 mg: 11.0; 6 mg: | N/A | Nausea (25%), diarrhea (22%), transient tachycardia (4 mg); nausea (28%), diarrhea (25%), transient tachycardia (6 mg) |

| Dong et al[64], 2025 | 3 | N/A | -14.8 | N/A | Mild GI (vomiting, nausea) |

| Classification | Drug | Mechanism of action | Test method | Body weight | Metabolism | Glucose | Cardiovascular | Central nervous system | Ref. |

| GLP-1R agonist | Liraglutide | GLP-1R | Controlled clinical trials | Decreased MAlb/creatinine; reduced C-reactive protein by 0.8-0.2; decreased IL-6; CD34+, CD133+, and other circulating progenitor cells and endothelial progenitor cell concentrations were elevated in the liraglutide-treated group | Significant difference in TcPO2 at 18 months in liraglutide group | Higher increase in vascular endothelial growth factor A | [52] | ||

| Semaglutide | GLP-1R | Clinical controlled trial | Body weight -13.7% and waist circumference least squares mean -13.0 cm in semaglutide group at week 72 | Smaller decrease in mean annual eGFR slope; reduced BNIP3 expression in mitochondria via PI3K/AKT pathway | Trial of effects on AD biomarkers and neuroinflammation will provide data on potential disease-modifying effects of semaglutide | [65-68] | |||

| Tirzepatide | GLP-1R | Clinical controlled trials, basic animal studies | Percentage of least squares mean of body weight in tirzepatide group -20.2%, least squares mean of waist circumference -18.4 cm | Regulates Aβ-induced reactive oxygen species production and mitochondrial membrane potential; reduces mitochondrial function, ATP levels in astrocytes via GLP-1R | Reduces blood glucose level and increases mRNA expression of GLP-1R, SACF1, etc. in the hypothalamus of APP/PS1 mice | Decrease the expression level of GLP-1R and GFAP proteins in the cortex; Decrease Aβ-induced neuronal apoptosis; Increase mRNA expression of Glut1, CAS, etc. in the cortex | [65,69] | ||

| GLP-1R inhibitors | SGLT-2 inhibitor | Decreases glucose reabsorption in proximal tubules | Meta-analysis | Improved HRQoL parameters of KCCQ-CSS scores, KCCQ-OSS scores and exercise capacity 6MWTD | SGLT2i significantly reduced AF risk; SGLT2i was associated with a borderline reduced risk of SCD; SGLT-2 was detected in epithelial cells of proximal tubules, and ETA, SGLT-2 receptor in cardiomyocytes | [70-72] | |||

| GLP-1R/GCGR dual-target agonist | Mazdutide | GLP-1R/GCGR | Clinical controlled trials, basic animal studies | Substantial reduction in body weight, BMI | Regulates the expression level of GCGR, Slc22a7 and other genes, regulates glucose and lipid metabolism, purine metabolism, bile secretion, to achieve the effect of lowering uric acid | Reduces the precursors of uric acid production and regulates glucose and lipid metabolism | Up-regulate the expression level of GCGR, Aqp2 and other genes, and down-regulates the expression level of Dnmt3a, Rest, and other genes | Improves cognitive performance in db/db mice; Enhancement of neural structure and brain tissue integrity | [42,64,73] |

Common adverse effects: Ji et al[63] conducted a comprehensive study on the safety profile of mazdutide, revealing that both the experimental and placebo groups experienced low to moderate adverse effects. Reported adverse effects included upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, decreased appetite, nausea, urinary tract infections, abdominal distention, and vomiting. The findings indicated that gastrointestinal side effects predominated, with an increased incidence correlating with higher mazdutide dosages. Additionally, a small number of patients developed serious conditions, including anal fistula, cholecystitis, obstructive pancreatitis, electrolyte imbalances, and lipometritis during treatment. However, these occurrences were primarily attributed to pre-existing underlying health issues rather than a direct consequence of mazdutide. Chen et al[74] have thoroughly summarized the adverse neurological effects of GLP-1R agonists, including dizziness, headache, fatigue, drowsiness, and brain fog. Furthermore, the treatment can also induce epileptic seizures, Wernicke encephalopathy with symptoms such as nystagmus, ophthalmoparesis, ataxia, and con

Long-term concerns: Low-dose mazdutide has been shown to clinically impact heart rate, with a peak effect observed during the dose-escalation phase. However, as the dose increases further, heart rate does not continue to rise. Most of the cardiac symptoms observed clinically to date are transient episodes of sinus tachycardia. Cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) are crucial for evaluating the cardiovascular safety and benefits of drugs used to treat various conditions, including obesity[76,77]. Although mazdutide is currently considered to have potential cardiovascular side effects, its underlying mechanisms and key changes are still under investigation. Isolated cases of cardiovascular events, such as arrhythmias and atrial fibrillation, observed following the use of mazdutide have raised concerns about its long-term cardiac safety. The heart primarily relies on fatty acid oxidation and other metabolic pathways for energy to maintain normal rhythm and pumping function. The sustained activation of fatty acid oxidation by mazdutide may alter the heart's substrate utilization over time, disrupting energy metabolism homeostasis, and potentially impairing cardiac function, including myocardial cell damage, decreased cardiac performance, or arrhythmias. However, the available CVOT data associated with mazdutide does not yet support an assessment of its long-term safety. Therefore, future evaluation of its cardiovascular safety can be achieved by assessing its impact on three major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with high cardiovascular risk T2DM: Cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke.

Pancreatitis and thyroid C-cell carcinoma have been key concerns in monitoring the safety of GLP-1R agonists. A 2013 study indicated a potential association between GLP-1R drugs and an increased risk of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer[78]. Basic research has demonstrated that medications such as liraglutide can elevate serum lipase and amylase levels in patients; however, these increases do not directly predict the onset of acute pancreatitis[79]. More recently, some researchers have identified that DPP-4 inhibitors, which work through GLP-1 pathways, may raise the risk of acute pancreatitis in individuals with T2DM[80]. Although definitive evidence linking GLP-1R agonists to pancreatic cancer is lacking, the hypothesis that GLP-1R are expressed in pancreatic ductal epithelial cells suggests that these drugs could lead to ductal hyperplasia and dilatation, indicating potential risks. Another significant concern is the association of GLP-1R agonists with the risk of thyroid C-cell carcinoma. Research indicates that these agonists may elevate the risk of various thyroid cancers, particularly medullary thyroid cancer, after 1-3 years of treatment[81]. Although studies have reported the targeting effects of GLP-1R agonists on thyroid C cells in rodent models[82], there is a notable lack of experimental evidence in human and primate subjects[83]. Additionally, GCG and GLP-1 exhibit both synergistic and antagonistic effects on regulating glucose and energy homeostasis. In clinical trials of mazdutide, no cases of pancreatitis and thyroid C-cell carcinoma were observed. However, further experimental investigation is required to determine whether mazdutide exerts any detrimental effects when considering the interplay of these mechanisms.

Mazdutide’s notable effects on weight control and metabolic improvement primarily stem from its sustained activation of fat oxidation. The liver plays a crucial role as a metabolic organ, overseeing a range of complex functions, including material synthesis, decomposition, and transformation[84]. The long-term impact of mazdutide on liver energy me

Adverse effects of GLP-1R inhibitors: Radiolabeled exendin significantly enhances GLP-1R molecular imaging[85]. In preclinical models, the uptake of radiolabeled exendin is correlated with β-cell mass[86], providing a crucial foundation for understanding the pathophysiology of related diseases[87]. In the research and application of drugs related to the GLP-1 signaling pathway, GLP-1R inhibitors, such as exendin (9-39), do not activate the receptor to cause internalization of the peptide-receptor complex compared to GLP-1R agonists, so its side effects are significantly fewer than agonists and it has strong tolerability[88]. However, current research on exendin (9-39) remains at a basic stage, and due to the lack of clinical data, its adverse effects have not been comprehensively evaluated[89].

Previous studies have shown that exendin (9-39) significantly affects arterial blood pressure and heart rate at high concentrations, leading us to consider that its primary adverse effects may involve interference with cardiovascular regulation. For instance, one study found that exendin (9-39) could negate the effects of GLP-1R agonists on increasing renal sympathetic nerve activity and mean arterial pressure[90]. Wei et al[91] demonstrated that the combination of GLP-1 with a GLP-1R inhibitor resulted in a significantly lower reduction in microvascular permeability compared to GLP-1 alone. This indicates that GLP-1 may influence vascular permeability independently of the GLP-1R, offering insights into the adverse cardiovascular reactions associated with GLP-1R inhibitors. However, since exendin (9-39) stimulates the secretion of all L cell products, including GLP-1, it presents a complex profile of effects[92]. Additionally, exendin (9-39) lacks an internalization process, making its mechanism of action challenging to elucidate. These factors create significant hurdles for subsequent studies aiming to isolate GLP-1 for verification using exendin (9-39). Notably, cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), which are generally 5 to 10 amino acids in length, can be internalized by cells without receptor activation[93,94]. Penetratin (Pen), derived from the antennapedia homeobox protein of Drosophila melanogaster, is one such CPP[95]. Studies have indicated that Pen can enhance the binding and internalization of exendin (9-39) in vitro, laying the groundwork for combining Pen with exendin variants for GLP-1R-directed approaches[96,97]. Future research could employ image-guided surgery and targeted photodynamic therapy to investigate the cellular internalization of GLP-1R inhibitors, further exploring their potential for weight loss treatment[98].

For safety reasons, glucose infusion needs to be monitored during exendin imaging to avoid severe hypoglycemia. This concern underscores the necessity for developing highly effective inhibitors. Calabria et al[99] demonstrated through experiments on mice and humans that short-term intravenous infusion of exendin (9-39) inhibits insulin secretion, resulting in significantly increased fasting blood glucose concentrations. This finding suggests that inhibiting GLP-1 signaling is an effective strategy for reversing GLP-1-induced hypoglycemia. Further research has revealed that GLP-1R inhibitors exert both pancreatic and extrapancreatic effects[100]. They contribute to increased blood glucose levels through several mechanisms. Under normal conditions, GLP-1 enhances insulin's ability to promote nutrient transport to peripheral tissues such as muscle cells. In contrast, GLP-1R inhibitors antagonize this synergistic effect, reducing glucose transport and leading to its retention in the bloodstream[101]. Studies have shown that GLP-1R agonists can enhance cellular glucose uptake by increasing the translocation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) to the cell surface under insulin stimulation[102]. In contrast, GLP-1R inhibitors hinder GLUT4 translocation, decrease insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, and impair glucose uptake and utilization, ultimately diminishing blood glucose clearance efficiency. These inhibitors also reduce insulin extraction by the liver, which weakens the liver's inhibitory effect on endogenous glucose production. Consequently, more insulin enters peripheral circulation, but due to reduced sensitivity, it fails to exert a hypoglycemic effect, causing blood glucose levels to rise. For instance, Zheng et al[103] noted a 28% decrease in liver insulin extraction in children with ATP-sensitive potassium channel congenital hyperinsulinism during the mixed meal tolerance test. Moreover, studies have shown that during the infusion of exendin (9-39)[104], blocking GLP-1R sig

Antibody-drug conjugates use the targeting specificity of antibodies to recognize antigens and enter cells, undergo lysosomal degradation, and release the effective payload to exert its effects. This method of using antibodies to promote the delivery of small molecules to antigens allows a single molecule to simultaneously exert the effects of agonists and inhibitors on receptors. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), another incretin hormone, plays a critical role in regulating human metabolism, similar to GLP-1 and GCG. Recent studies have demonstrated that the combined use of GIP receptor (GIPR) inhibitors and GLP-1R agonists significantly enhances weight loss efficacy. AMG 133 (maridebart cafraglutide) exemplifies this, as phase 1 clinical trials indicated its potential by conjugating a monoclonal anti-human GIPR inhibitor antibody with two GLP-1 analog agonist peptides through amino acid linkages[105]. In experimental models involving obese mice, crab-eating macaques, and human subjects, this conjugate exhibited sub

The combined use of agonists and antagonists appears to present a paradox; however, studies in mice and non-human primates have demonstrated that this combination can yield superior weight loss results compared to single-drug treatments. As previously mentioned, the side effects associated with GLP-1R inhibitors are significantly less than those of agonists. Perhaps we can speculate that combining GLP-1R inhibitors with mazdutide could produce a synergistic effect, enhancing weight loss and metabolic improvement while minimizing adverse effects. For instance, AMG 133, influenced by incretin during administration, leads to only mild gastrointestinal side effects within 8-12 hours following the first dose. Importantly, the severity of these side effects does not increase with higher doses compared to a single agonist, providing evidence for the potential efficacy of combining agonists and inhibitors. Optimizing the balance between efficacy and side effects may be achievable through the combination of mazdutide with GLP-1R inhibitors. By leveraging the complementary effects of different drugs, this approach could lower the risk of side effects associated with high-dose monotherapy, thereby reducing patient discomfort and potentially decreasing treatment costs, contributing positively to obesity treatment within the healthcare system. Nevertheless, it is essential to highlight that while the stimulation of hepatic glucose production by GCG is transient, its long-term stimulation mechanisms remain unclear. Maintaining a balance between the activities of the two receptors continues to be a major research focus[108]. After combining with GLP-1R inhibitors, it will be crucial to balance receptor affinity and control variables to maximize the weight loss effect.

Compared to single-target drugs, mazdutide represents a significant improvement in both weight reduction and overall metabolic regulation. As a new weight-loss treatment, it shifts the focus from merely achieving weight loss to restoring metabolic homeostasis—encompassing holistic management of weight, metabolism, and complications. However, despite the promising potential of mazdutide, current research is limited by several factors.

A significant challenge in understanding mazdutide lies in the insufficient systematic investigation of its receptor binding characteristics and the mechanisms of multi-organ metabolic regulation in basic research. Clinical trials show that varying dosages and increments yield different outcomes in terms of weight loss efficacy and the management of complications. Once mazdutide binds to its receptor, it activates key downstream proteins, with signal transduction intensity displaying nonlinear changes depending on dose adjustments. As a structurally more complex dual agonist, it remains uncertain whether mazdutide poses risks of accumulation, whether its elimination half-life is extended, and what the safety margins are at various dosages. Future research should leverage advanced technologies such as molecular biology, metabolomics, and single-cell sequencing to further clarify the precise mechanisms and interplay of complementary pharmacological effects between GCGR and GLP-1R. Notably, obesity often coexists with various metabolic dysregulations, which makes it difficult for single-agent therapies to achieve optimal outcomes. Given the significant role of GLP-1R inhibitors in glycemic control, future studies could investigate the combined use of mazdutide with them[109]. This strategy should utilize a stepwise dose-escalation clinical trial design, incorporating patient-specific characteristics to establish optimal combination dosages and treatment durations based on dose-response analyses.

Beyond pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics is a crucial parameter in understanding treatment outcomes. Many individuals with a BMI exceeding 30 kg/m2 require long-term medication to reach target weight and realize comprehensive cardiometabolic benefits. Natural fluctuations in hormone levels elicit distinctly different physiological responses in the body over short and long timeframes. However, a substantial number of patients discontinue treatment due to intolerable side effects. Current studies on mazdutide have primarily focused on short-term results, making it challenging to accurately assess its long-term efficacy and rare adverse reactions. Furthermore, most published studies on mazdutide have small sample sizes. Although available clinical data support mazdutide, current research has largely focused on standard populations at high risk for metabolic syndrome. Evidence on efficacy and safety remains limited for specific groups, including individuals with T2DM and obesity, cardiovascular failure, or renal insufficiency. While some patients with diabetes have been enrolled in current clinical trials, the primary focus has been on obese or metabolically abnormal populations. Whether mazdutide carries a dose-dependent risk of hyperglycemia in T2DM with obesity, and whether combination therapy with hypoglycemic agents is needed for blood glucose control, have yet to be examined. To date, no systematic analysis of the efficacy or safety of mazdutide has been conducted in adults aged 65 years and older. Common geriatric features, such as multiple comorbidities and slowed gastrointestinal motility, may affect the drug’s pharmacokinetics and tolerance of adverse reactions. Therefore, future studies should extend follow-up periods and collect and analyze safety data in real time during drug administration. Meanwhile, clinical trials should be conducted across diverse populations, with findings promptly fed back into basic research to foster a virtuous cycle of “basic research → clinical validation → mechanism re-exploration”. It is essential to note that studies on mazdutide have primarily centered on Chinese populations. China adopts lower BMI thresholds for overweight and obesity compared to those recommended by the World Health Organization, which may significantly restrict the generalizability of mazdutide’s therapeutic efficacy to individuals of different races and ethnicities. Therefore, while ensuring therapeutic efficacy, future research must also strengthen the evidence base regarding its applicability to specific populations and individual response variations to enhance the quality and effectiveness of its application in global weight management and metabolic disease treatment[110].

In comparison to previous studies, this review moves beyond a one-dimensional approach to efficacy assessment. We systematically explore multiple dimensions, including clinical trial design, potential challenges, and underlying mechanisms, thereby providing comprehensive and up-to-date resources for academic research in this area. By balancing the integrated effects of dual GLP-1R/GCGR dual-target agonist both in vivo and in vitro, mazdutide shows promising application potential. However, further research is essential to facilitate its clinical translation.

| 1. | Gažarová M, Galšneiderová M, Mečiarová L. Obesity diagnosis and mortality risk based on a body shape index (ABSI) and other indices and anthropometric parameters in university students. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2019;70:267-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pan XF, Wang L, Pan A. Epidemiology and determinants of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:373-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 1035] [Article Influence: 207.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (14)] |

| 3. | Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Powis J, Brinsden H, Gray M. World Obesity Atlas 2023. World Obesity Federation, United Kingdom, 2023. Available from: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/3454894/untitled/4255209/. |

| 4. | Nalisa DL, Cuboia N, Dyab E, Jackson IL, Felix HJ, Shoki P, Mubiana M, Oyedeji-Amusa M, Azevedo L, Jiang H. Efficacy and safety of Mazdutide on weight loss among diabetic and non-diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1309118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pocai A. Action and therapeutic potential of oxyntomodulin. Mol Metab. 2014;3:241-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu C, Xu H, Yuan F, Chen H, Sheng L, Chen W, Xie H, Xu H, Li X. Evaluating the bioequivalence and safety of liraglutide injection versus Victoza(®) in healthy Chinese subjects: a randomized, open, two-cycle, self-crossover phase I clinical trial. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1326865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Müller TD, Blüher M, Tschöp MH, DiMarchi RD. Anti-obesity drug discovery: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21:201-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 160.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nauck MA, Wefers J, Meier JJ. Treatment of type 2 diabetes: challenges, hopes, and anticipated successes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:525-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 38.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Doyle ME, Egan JM. Mechanisms of action of glucagon-like peptide 1 in the pancreas. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113:546-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 543] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ambery P, Parker VE, Stumvoll M, Posch MG, Heise T, Plum-Moerschel L, Tsai LF, Robertson D, Jain M, Petrone M, Rondinone C, Hirshberg B, Jermutus L. MEDI0382, a GLP-1 and glucagon receptor dual agonist, in obese or overweight patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, ascending dose and phase 2a study. Lancet. 2018;391:2607-2618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Di Prospero NA, Yee J, Frustaci ME, Samtani MN, Alba M, Fleck P. Efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1/glucagon receptor co-agonist JNJ-64565111 in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity: A randomized dose-ranging study. Clin Obes. 2021;11:e12433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ji L, Jiang H, An P, Deng H, Liu M, Li L, Feng L, Song B, Han-Zhang H, Ma Q, Qian L. IBI362 (LY3305677), a weekly-dose GLP-1 and glucagon receptor dual agonist, in Chinese adults with overweight or obesity: A randomised, placebo-controlled, multiple ascending dose phase 1b study. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Banting FG, Best CH, Collip JB, Campbell WR, Fletcher AA. Pancreatic Extracts in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Can Med Assoc J. 1922;12:141-146. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Holst JJ, Cherrington AD, Finan B, Gluud LL, Dean ED, Campbell JE, Bloom SR, Tan TM, Knop FK, Müller TD. 100 years of glucagon and 100 more. Diabetologia. 2023;66:1378-1394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Drucker DJ. GLP-1 physiology informs the pharmacotherapy of obesity. Mol Metab. 2022;57:101351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 58.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li QX, Gao H, Guo YX, Wang BY, Hua RX, Gao L, Shang HW, Lu X, Xu JD. GLP-1 and Underlying Beneficial Actions in Alzheimer's Disease, Hypertension, and NASH. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:721198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jones B. The therapeutic potential of GLP-1 receptor biased agonism. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179:492-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bellavance D, Chua S, Mashimo H. Gastrointestinal Motility Effects of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2025;27:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Al-Noshokaty TM, Abdelhamid R, Abdelmaksoud NM, Khaled A, Hossam M, Ahmed R, Saber T, Khaled S, Elshaer SS, Abulsoud AI. Unlocking the multifaceted roles of GLP-1: Physiological functions and therapeutic potential. Toxicol Rep. 2025;14:101895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hu Y, Huang H, Xiang R. GCGR: novel potential therapeutic target for chronic kidney disease. Sci China Life Sci. 2024;67:1542-1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bomholt AB, Johansen CD, Christensen JB, Kjeldsen SAS, Galsgaard KD, Winther-Sørensen M, Serizawa R, Hornum M, Porrini E, Pedersen J, Ørskov C, Gluud LL, Sørensen CM, Holst JJ, Albrechtsen R, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ. Evaluation of commercially available glucagon receptor antibodies and glucagon receptor expression. Commun Biol. 2022;5:1278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Müller TD, Finan B, Clemmensen C, DiMarchi RD, Tschöp MH. The New Biology and Pharmacology of Glucagon. Physiol Rev. 2017;97:721-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nason SR, Antipenko J, Presedo N, Cunningham SE, Pierre TH, Kim T, Paul JR, Holleman C, Young ME, Gamble KL, Finan B, DiMarchi R, Hunter CS, Kharitonenkov A, Habegger KM. Glucagon receptor signaling regulates weight loss via central KLB receptor complexes. JCI Insight. 2021;6:e141323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kleinert M, Sachs S, Habegger KM, Hofmann SM, Müller TD. Glucagon Regulation of Energy Expenditure. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang Y, Han C, Zhu W, Yang G, Peng X, Mehta S, Zhang J, Chen L, Liu Y. Glucagon Potentiates Insulin Secretion Via β-Cell GCGR at Physiological Concentrations of Glucose. Cells. 2021;10:2495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Li Y, Zhou Q, Dai A, Zhao F, Chang R, Ying T, Wu B, Yang D, Wang MW, Cong Z. Structural analysis of the dual agonism at GLP-1R and GCGR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120:e2303696120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Novikoff A, Müller TD. The molecular pharmacology of glucagon agonists in diabetes and obesity. Peptides. 2023;165:171003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Stangerup I, Kjeldsen SAS, Richter MM, Jensen NJ, Rungby J, Haugaard SB, Georg B, Hannibal J, Møllgård K, Wewer Albrechtsen NJ, Bjørnbak Holst C. Glucagon does not directly stimulate pituitary secretion of ACTH, GH or copeptin. Peptides. 2024;176:171213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gelling RW, Du XQ, Dichmann DS, Romer J, Huang H, Cui L, Obici S, Tang B, Holst JJ, Fledelius C, Johansen PB, Rossetti L, Jelicks LA, Serup P, Nishimura E, Charron MJ. Lower blood glucose, hyperglucagonemia, and pancreatic alpha cell hyperplasia in glucagon receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1438-1443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Parker JC, Andrews KM, Allen MR, Stock JL, McNeish JD. Glycemic control in mice with targeted disruption of the glucagon receptor gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:839-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mukharji A, Drucker DJ, Charron MJ, Swoap SJ. Oxyntomodulin increases intrinsic heart rate through the glucagon receptor. Physiol Rep. 2013;1:e00112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Conceição-Furber E, Coskun T, Sloop KW, Samms RJ. Is Glucagon Receptor Activation the Thermogenic Solution for Treating Obesity? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:868037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kueh MTW, Chong MC, Miras AD, le Roux CW. Oxyntomodulin physiology and its therapeutic development in obesity and associated complications. J Physiol. 2025;603:7683-7693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Darbalaei S, Yuliantie E, Dai A, Chang R, Zhao P, Yang D, Wang MW, Sexton PM, Wootten D. Evaluation of biased agonism mediated by dual agonists of the GLP-1 and glucagon receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;180:114150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gogineni P, Melson E, Papamargaritis D, Davies M. Oral glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and combinations of entero-pancreatic hormones as treatments for adults with type 2 diabetes: where are we now? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2024;25:801-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhang B, Cheng Z, Chen J, Zhang X, Liu D, Jiang H, Ma G, Wang X, Gan S, Sun J, Jin P, Yi J, Shi B, Ma J, Ye S, Wang G, Ji L, Gu X, Yu T, An P, Deng H, Li H, Li L, Ma Q, Qian L, Yang W. Efficacy and Safety of Mazdutide in Chinese Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Diabetes Care. 2024;47:160-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ashraf MT, Ahmed Rizvi SH, Kashif MAB, Shakeel Khan MK, Ahmed SH, Asghar MS. Efficacy of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies in delaying the progression of recent-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review, meta-analyses and meta-regression. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25:3377-3389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Yue D, Hua X, Zhu L, Wang J, Gu L, Yuan Z, Jian W, Chen Y, Meng G. Development of a risk prediction model for gastrointestinal adverse events associated with semaglutide administration in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025;16:1684395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Minnetti M, Barazzoni R, Batsis JA, Busetto L, Yumuk V, Poggiogalle E, Weijs PJM, Donini LM. The Integration of Lifestyle Modification Advice and Diet and Physical Exercise Interventions: Cornerstones in the Management of Obesity with Incretin Mimetics. Obes Facts. 2025;1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Townsend LK, Steinberg GR. AMPK and the Endocrine Control of Metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2023;44:910-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chianelli M, Busetto L, Attanasio R, Guglielmi R, Cozzi R, Grimaldi F, Frasoldati A, Persichetti A, Papini E, Nicolucci A. From awareness to action: evolving endocrinologist practices in obesity treatment in Italy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025;16:1705670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ji L, Jiang H, Bi Y, Li H, Tian J, Liu D, Zhao Y, Qiu W, Huang C, Chen L, Zhong S, Han J, Zhang Y, Lian Q, Yang P, Lv L, Gu J, Liu Z, Deng H, Wang Y, Li L, Pei L, Qian L; GLORY-1 Investigators. Once-Weekly Mazdutide in Chinese Adults with Obesity or Overweight. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:2215-2225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zimmermann T, Thomas L, Baader-Pagler T, Haebel P, Simon E, Reindl W, Bajrami B, Rist W, Uphues I, Drucker DJ, Klein H, Santhanam R, Hamprecht D, Neubauer H, Augustin R. BI 456906: Discovery and preclinical pharmacology of a novel GCGR/GLP-1R dual agonist with robust anti-obesity efficacy. Mol Metab. 2022;66:101633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yazawa R, Ishida M, Balavarca Y, Hennige AM. A randomized Phase I study of the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of BI 456906, a dual glucagon receptor/glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, in healthy Japanese men with overweight/obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25:1973-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | le Roux CW, Steen O, Lucas KJ, Startseva E, Unseld A, Hennige AM. Glucagon and GLP-1 receptor dual agonist survodutide for obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024;12:162-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 59.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Thomas L, Martel E, Rist W, Uphues I, Hamprecht D, Neubauer H, Augustin R. The dual GCGR/GLP-1R agonist survodutide: Biomarkers and pharmacological profiling for clinical candidate selection. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:2368-2378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Parker VER, Robertson D, Wang T, Hornigold DC, Petrone M, Cooper AT, Posch MG, Heise T, Plum-Moerschel L, Schlichthaar H, Klaus B, Ambery PD, Meier JJ, Hirshberg B. Efficacy, Safety, and Mechanistic Insights of Cotadutide, a Dual Receptor Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 and Glucagon Agonist. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:dgz047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Asano M, Sekikawa A, Kim H, Gasser RA Jr, Robertson D, Petrone M, Jermutus L, Ambery P. Pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability and efficacy of cotadutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucagon receptor dual agonist, in phase 1 and 2 trials in overweight or obese participants of Asian descent with or without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23:1859-1867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Bosch R, Petrone M, Arends R, Vicini P, Sijbrands EJG, Hoefman S, Snelder N. Characterisation of cotadutide's dual GLP-1/glucagon receptor agonistic effects on glycaemic control using an in vivo human glucose regulation quantitative systems pharmacology model. Br J Pharmacol. 2024;181:1874-1885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Boland ML, Laker RC, Mather K, Nawrocki A, Oldham S, Boland BB, Lewis H, Conway J, Naylor J, Guionaud S, Feigh M, Veidal SS, Lantier L, McGuinness OP, Grimsby J, Rondinone CM, Jermutus L, Larsen MR, Trevaskis JL, Rhodes CJ. Resolution of NASH and hepatic fibrosis by the GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonist Cotadutide via modulating mitochondrial function and lipogenesis. Nat Metab. 2020;2:413-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Spezani R, Marinho TS, Reis TS, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Cotadutide (GLP-1/Glucagon dual receptor agonist) modulates hypothalamic orexigenic and anorexigenic neuropeptides in obese mice. Peptides. 2024;173:171138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Caruso P, Maiorino MI, Longo M, Maio A, Scappaticcio L, Di Martino N, Carbone C, Barrasso M, Caputo M, Gicchino M, Bellastella G, Giugliano D, Esposito K. Liraglutide improves peripheral perfusion and markers of angiogenesis and inflammation in people with type 2 diabetes and peripheral artery disease: An 18-month follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27:3891-3900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Hasib A. Multiagonist Unimolecular Peptides for Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: Current Advances and Future Directions. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes. 2020;13:1179551420905844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Nicze M, Dec A, Borówka M, Krzyżak D, Bołdys A, Bułdak Ł, Okopień B. Molecular Mechanisms behind Obesity and Their Potential Exploitation in Current and Future Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:8202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Jungnik A, Arrubla Martinez J, Plum-Mörschel L, Kapitza C, Lamers D, Thamer C, Schölch C, Desch M, Hennige AM. Phase I studies of the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the dual glucagon receptor/glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist BI 456906. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25:1011-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Parker VER, Robertson D, Erazo-Tapia E, Havekes B, Phielix E, de Ligt M, Roumans KHM, Mevenkamp J, Sjoberg F, Schrauwen-Hinderling VB, Johansson E, Chang YT, Esterline R, Smith K, Wilkinson DJ, Hansen L, Johansson L, Ambery P, Jermutus L, Schrauwen P. Cotadutide promotes glycogenolysis in people with overweight or obesity diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Nat Metab. 2023;5:2086-2093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Nauck MA, Quast DR, Wefers J, Meier JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes - state-of-the-art. Mol Metab. 2021;46:101102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 1041] [Article Influence: 208.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Neumann J, Ahlrep U, Hofmann B, Gergs U. Inotropic effects of retatrutide in isolated human atrial preparations. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hu M, Cai X, Yang W, Zhang S, Nie L, Ji L. Effect of Hemoglobin A1c Reduction or Weight Reduction on Blood Pressure in Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist and Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitor Treatment in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Movahednasab M, Dianat-Moghadam H, Khodadad S, Nedaeinia R, Safabakhsh S, Ferns G, Salehi R. GLP-1-based therapies for type 2 diabetes: from single, dual and triple agonists to endogenous GLP-1 production and L-cell differentiation. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2025;17:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Welling MS, van Rossum EFC, van den Akker ELT. Antiobesity Pharmacotherapy for Patients With Genetic Obesity Due to Defects in the Leptin-Melanocortin Pathway. Endocr Rev. 2025;46:418-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Ji L, Gao L, Jiang H, Yang J, Yu L, Wen J, Cai C, Deng H, Feng L, Song B, Ma Q, Qian L. Safety and efficacy of a GLP-1 and glucagon receptor dual agonist mazdutide (IBI362) 9 mg and 10 mg in Chinese adults with overweight or obesity: A randomised, placebo-controlled, multiple-ascending-dose phase 1b trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;54:101691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Ji L, Jiang H, Cheng Z, Qiu W, Liao L, Zhang Y, Li X, Pang S, Zhang L, Chen L, Yang T, Li Y, Qu S, Wen J, Gu J, Deng H, Wang Y, Li L, Han-Zhang H, Ma Q, Qian L. A phase 2 randomised controlled trial of mazdutide in Chinese overweight adults or adults with obesity. Nat Commun. 2023;14:8289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Dong W, Bai J, Yuan Q, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Yang M, Li H, Zhao Z, Jiang H. Mazdutide, a dual agonist targeting GLP-1R and GCGR, mitigates diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction: mechanistic insights from multi-omics analysis. EBioMedicine. 2025;117:105791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Aronne LJ, Horn DB, le Roux CW, Ho W, Falcon BL, Gomez Valderas E, Das S, Lee CJ, Glass LC, Senyucel C, Dunn JP; SURMOUNT-5 Trial Investigators. Tirzepatide as Compared with Semaglutide for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2025;393:26-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 185.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Cummings JL, Atri A, Feldman HH, Hansson O, Sano M, Knop FK, Johannsen P, León T, Scheltens P. evoke and evoke+: design of two large-scale, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies evaluating efficacy, safety, and tolerability of semaglutide in early-stage symptomatic Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2025;17:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Perkovic V, Tuttle KR, Rossing P, Mahaffey KW, Mann JFE, Bakris G, Baeres FMM, Idorn T, Bosch-Traberg H, Lausvig NL, Pratley R; FLOW Trial Committees and Investigators. Effects of Semaglutide on Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:109-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 935] [Article Influence: 467.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 68. | Li X, Luo W, Tang Y, Wu J, Zhang J, Chen S, Zhou L, Tao Y, Tang Y, Wang F, Huang Y, Jose PA, Guo L, Zeng C. Semaglutide attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by ameliorating BNIP3-Mediated mitochondrial dysfunction. Redox Biol. 2024;72:103129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Yang S, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Tang Q, Li Y, Du Y, Yu P. Tirzepatide shows neuroprotective effects via regulating brain glucose metabolism in APP/PS1 mice. Peptides. 2024;179:171271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Liao J, Ebrahimi R, Ling Z, Meyer C, Martinek M, Sommer P, Futyma P, Di Vece D, Schratter A, Acou WJ, Zhu L, Kiuchi MG, Liu S, Yin Y, Pürerfellner H, Templin C, Chen S. Effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on arrhythmia events: insight from an updated secondary analysis of > 80,000 patients (the SGLT2i-Arrhythmias and Sudden Cardiac Death). Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23:78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Guo Z, Wang L, Yu J, Wang Y, Yang Z, Zhou C. Correction to: The role of SGLT-2 inhibitors on health-related quality of life, exercise capacity, and volume depletion in patients with chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45:800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Williams TL, Kuc RE, Paterson AL, Abraham GR, Pullinger AL, Maguire JJ, Sinha S, Greasley PJ, Ambery P, Davenport AP. Co-localization of the sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 channel (SGLT-2) with endothelin ETA and ETB receptors in human cardiorenal tissue. Biosci Rep. 2024;44:BSR20240604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Wang Y, Zhang M, Dong K, Yin X, Hao C, Zhang W, Irfan M, Chen L, Wang Y. Metabolomic and transcriptomic exploration of the uric acid-reducing flavonoids biosynthetic pathways in the fruit of Actinidia arguta Sieb. Zucc. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1025317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Chen H, Liu S, Gao S, Shi H, Yan Y, Xu Y, Fang J, Wang W, Chen H, Liu Z. Pharmacovigilance analysis of neurological adverse events associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists based on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Sci Rep. 2025;15:18063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Bezin J, Gouverneur A, Pénichon M, Mathieu C, Garrel R, Hillaire-Buys D, Pariente A, Faillie JL. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and the Risk of Thyroid Cancer. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:384-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Nicholls SJ, Bhatt DL, Buse JB, Prato SD, Kahn SE, Lincoff AM, McGuire DK, Nauck MA, Nissen SE, Sattar N, Zinman B, Zoungas S, Basile J, Bartee A, Miller D, Nishiyama H, Pavo I, Weerakkody G, Wiese RJ, D'Alessio D; SURPASS-CVOT investigators. Comparison of tirzepatide and dulaglutide on major adverse cardiovascular events in participants with type 2 diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: SURPASS-CVOT design and baseline characteristics. Am Heart J. 2024;267:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 75.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Home P. Cardiovascular outcome trials of glucose-lowering medications: an update. Diabetologia. 2019;62:357-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Singh S, Chang HY, Richards TM, Weiner JP, Clark JM, Segal JB. Glucagonlike peptide 1-based therapies and risk of hospitalization for acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based matched case-control study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:534-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Quast DR, Nauck MA, Schenker N, Menge BA, Kapitza C, Meier JJ. Macronutrient intake, appetite, food preferences and exocrine pancreas function after treatment with short- and long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23:2344-2353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Abd El Aziz M, Cahyadi O, Meier JJ, Schmidt WE, Nauck MA. Incretin-based glucose-lowering medications and the risk of acute pancreatitis and malignancies: a meta-analysis based on cardiovascular outcomes trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:699-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Kelly CA, Sipos JA. Approach to the Patient With Thyroid Nodules: Considering GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2025. 110:e2080-e2087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Rosol TJ. On-target effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on thyroid C-cells in rats and mice. Toxicol Pathol. 2013;41:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Chiu WY, Shih SR, Tseng CH. A review on the association between glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and thyroid cancer. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:924168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Sandoval DA, D'Alessio DA. Physiology of proglucagon peptides: role of glucagon and GLP-1 in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:513-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Jansen TJP, van Lith SAM, Boss M, Brom M, Joosten L, Béhé M, Buitinga M, Gotthardt M. Exendin-4 analogs in insulinoma theranostics. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2019;62:656-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Joosten L, Brom M, Peeters H, Bos D, Himpe E, Bouwens L, Boerman O, Gotthardt M. Measuring the Pancreatic β Cell Mass in Vivo with Exendin SPECT during Hyperglycemia and Severe Insulitis. Mol Pharm. 2019;16:4024-4030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Cnop M, Welsh N, Jonas JC, Jörns A, Lenzen S, Eizirik DL. Mechanisms of pancreatic beta-cell death in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: many differences, few similarities. Diabetes. 2005;54 Suppl 2:S97-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1089] [Cited by in RCA: 1173] [Article Influence: 55.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Craig CM, Lawler HM, Lee CJE, Tan M, Davis DB, Tong J, Glodowski M, Rogowitz E, Karaman R, McLaughlin TL, Porter L. PREVENT: A Randomized, Placebo-controlled Crossover Trial of Avexitide for Treatment of Postbariatric Hypoglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:e3235-e3248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Barragán JM, Rodríguez RE, Eng J, Blázquez E. Interactions of exendin-(9-39) with the effects of glucagon-like peptide-1-(7-36) amide and of exendin-4 on arterial blood pressure and heart rate in rats. Regul Pept. 1996;67:63-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Christ E, Wild D, Ederer S, Béhé M, Nicolas G, Caplin ME, Brändle M, Clerici T, Fischli S, Stettler C, Ell PJ, Seufert J, Gloor B, Perren A, Reubi JC, Forrer F. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor imaging for the localisation of insulinomas: a prospective multicentre imaging study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1:115-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 91. | Wei T, Cui X, Jiang Y, Wang K, Wang D, Li F, Lin X, Gu L, Yang K, Yang J, Hong T, Wei R. Glucagon Acting at the GLP-1 Receptor Contributes to β-Cell Regeneration Induced by Glucagon Receptor Antagonism in Diabetic Mice. Diabetes. 2023;72:599-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |