Published online Aug 25, 2017. doi: 10.5495/wjcid.v7.i3.38

Peer-review started: October 7, 2016

First decision: November 14, 2016

Revised: November 29, 2016

Accepted: February 10, 2017

Article in press: February 12, 2017

Published online: August 25, 2017

Processing time: 330 Days and 11.3 Hours

To assess healthcare seeking trends among Pakistani children with acute respiratory infections through comparative analysis between demographic health surveys (DHS) 2006-2007 and 2012-2013.

Data of the last born children 0-24 mo of age of the sampled households from both the DHS was analyzed after seeking permission from the DHS open access website. These were children who had suffered from cough and/or breathing difficulty in the past two weeks and sought health care thereafter. The trends of health care seeking were determined separately for the individual, household and community level according to the study parameters. χ2 test was applied to compare these trends. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Out of 2508 children in 2006-2007 there were 1590 with acute respiratory infections (ARI) according to case definition along with 2142 out of 3419 children in 2012-2013 DHS, whose data was analyzed. During 2006-2007, 69% cases sought healthcare for ARI which improved to 79% in 2012-2013. Additionally, it was revealed that when compared between 2006-2007 and 2012-2013, improvement in care seeking practices was observed among illiterate mothers (64% vs 77%) although there was minimal change in those literate. Similarly, those women working also showed an increase in healthcare seeking from 67% to 79%. Additionally, those belonging to low and middle socioeconomic class showed a marked increase as compared to those in the higher class where there was no significant change. Whereas those living in rural communities also showed an increase from 66% to 78%.

Increasing health budget, improving maternal education and strengthening multi-sectoral coordination are among the effective strategies to improve outcomes associated with healthcare seeking in ARI.

Core tip: Acute respiratory infections (ARI) contribute to childhood morbidity and mortality due to poor healthcare seeking among other causes. We aimed to identify the healthcare seeking trends among Pakistani children with ARI through comparative analysis between DHS 2006-2007 and 2012-2013. Data of last born children 0-24 mo was analyzed. In 2006-2007, 69% cases sought healthcare which improved to 79% in 2012-2013. Improvement was observed among poor, illiterate mothers, those working, and/or living in rural communities. It is therefore, important to develop strategies and interventions focusing on this category of caretakers to improve the outcome associated with ARI.

- Citation: Mahmood H, Khan SM, Abbasi S, Sheraz Y. Healthcare seeking trends in acute respiratory infections among children of Pakistan. World J Clin Infect Dis 2017; 7(3): 38-45

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3176/full/v7/i3/38.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5495/wjcid.v7.i3.38

Acute respiratory infections (ARI), in general, and pneumonia, in particular, continue to be the leading causes of childhood morbidity and mortality worldwide[1]. This leads to a substantial burden on the healthcare system and can cause serious complications leading to economic and psychological burden at the household level[1,2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, globally, over 2 million children die each year due to ARI with pneumonia[3] contributing to about one fifth of deaths of children aged less than five years[4]. Although numerous efforts have been put forth by the global community to combat these infections yet there has been little improvement witnessed in the reduction of the incidence of these diseases globally[2]. In Pakistan more than 250000 children die each year due to pneumonia[5,6]. This makes Pakistan enlisted among the top five countries globally with the highest childhood mortality due to pneumonia, a preventable disease[3,7]. Over 80% of these deaths occur due to lack of adequate and timely healthcare seeking[2]. It is, therefore, important to seek appropriate health care timely when children develop signs of ARI which include cough accompanied by short rapid breathing[8].

Studies have documented that delayed health care seeking behavior due to lack of knowledge regarding level of seriousness of the disease are among the leading causes[9-11]. In a formative research conducted in Nepal, Bangladesh and Pakistan regarding care seeking practices in the rural communities for newborn care, it was found that danger signs were not comprehended by the caretakers, therefore they mostly sought treatment from the local healers, i.e., homeopaths or non-qualified practitioners. Further, the traditional beliefs of influence of evil spirits, lack of understanding and awareness regarding the disease, distance from healthcare facilities, and high cost of treatment are hurdles in healthcare seeking behavior[12]. In another study conducted in Nigeria regarding the care seeking practices of childhood illnesses, 62% of the cases sought care beyond 24 h after the initiation of illness with 57% dealt with at home[13]. Another study conducted in Nigeria determining the effects socio-demographic characteristics on care seeking trends showed that high socioeconomic class and high maternal education were the major factors contributing towards early health care seeking from health facility[14]. In Pakistan, a study conducted to assess the healthcare seeking patterns in diarrhea among uneducated mothers of low resource peri urban Karachi showed that lack of transport and high cost of therapy are the major reasons for not seeking healthcare[15]. In a similar study conducted in rural Ecuador, it was found that lack of recognition of the danger signs of acute respiratory illnesses led to delayed care seeking irrespective of the socioeconomic status[16].

It is, therefore, important to understand the factors leading to poor health seeking behaviors among the caretakers of children suffering from ARI. This can assist in developing effective strategies to improve survival of children under five of developing countries. ARI continues to be among the major health problems in Pakistan, especially when there has been limited evidence generated regarding the health care seeking behavior over the past decade. We aim to assess the trends of the health care seeking behaviors among caretakers of children with ARI especially pneumonia in Pakistan with respect to the demographic health surveys (DHS) conducted during 2006-2007 and 2012-2013.

Acute respiratory illnesses: The cases of ARI were screened on the basis of children having cough, fast breathing or difficult breathing during the past two weeks according to the DHS questionnaire. These illnesses were divided into those who had “pneumonia” and those with “no pneumonia”. Those cases which only had symptoms of cough and fever were labeled as “no pneumonia”. Those cases which had fast breathing or difficult breathing due to involvement in the chest were labeled as “pneumonia”.

Care seeking: Care seeking was defined as when the caretaker sought advice or treatment for the illness from any source according to the DHS questionnaire. This included all types of care sought, either traditional or formal. It included whether visiting a government or private hospital, private clinics or doctors, Lady Health Workers, homeopath doctor or other primary level healthcare settings. The study outcome was dichotomized as the one who sought care and the one who did not seek care for ARI.

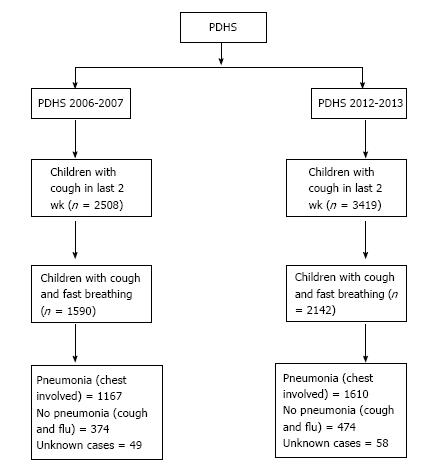

Data source: It is retrospective study whereby secondary data from datasets of 2006-2007 and 2012-2013 Pakistan demographic health survey (PDHS), carried out by the National Institute of Population Studies, was utilized after seeking permission from the Demographic Health Survey Program under USAID. The survey in both the cases was designed to provide information on maternal and child health. The sampling methodology employed in both the surveys was multistage stratified cluster sampling whereby urban and rural samples were drawn separately. The sample was nationally representative in line with the population distribution in each province of the country. Random household sampling was conducted to select the respondents for the survey. Considering this is a sub analysis of an existing dataset therefore consent from the participants of the survey was not sought as the National Institute of Population studies had taken prior consent upon completion of the survey. The data set was downloaded from the public access website (http://www.measuredhs.com). In the 2006-2007 survey 10023 respondents were surveyed whereas in the 2012-2013 survey the sample was of 12943 respondents. The response rate for the 2006-2007 survey was 94.5% whereas that of 2012-2013 was 93.1%. The data was inspected for quality, completeness of information and comparability of variables required for the present analysis. The variables from the data set were then selected according to the objectives and the files were constructed. We selected lastborn children from 0-24 mo of age at the time of the survey who had suffered from cough in the last two weeks and were living with respondents/mothers. There were 2508 cases identified with history of cough in DHS 2006-2007 whereas 2012-2013 had 3419 such cases. According to the case definition 1590 and 2142 children in DHS 2006-2007 and 2012-2013 respectively with acute respiratory symptoms were finally analyzed.

The data was analyzed using STATA 10.0 software. Frequency and percentages were calculated for ARI and its care seeking. The trends of health care seeking were determined separately for the individual, household and community level according to the study parameters. The variables included maternal age, maternal education, working status, father’s occupation, child age, gender, residence, place of delivery, delivery conducted by, socioeconomic status and geographical region. These variables were then coded and categorized. χ2 test was applied to compare the trends of the rates of care seeking among the different categories according to the study parameters. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by the biostatistician of Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Medical University, Islamabad, Pakistan.

There were 1590 children with the respiratory symptoms identified during the DHS 2006-2007, of which 1167 (73.3%) had pneumonia and 374 (23.5%) cases had no pneumonia according to case definition. On the other hand, during DHS 2012-2013 there were 2142 children with respiratory symptoms among which 1610 (75.1%) were with pneumonia and 474 (22%) were with no pneumonia. The underlying diagnosis of the rest of the cases in both the surveys was unknown. According to the DHS data, health care for ARI was sought by 1108 (69.6%) cases in 2006-2007 which included 813 pneumonia cases and 295 no pneumonia cases. Similarly 1707 (79.7%) children sought health care in 2012-2013 with 1276 pneumonia and 431 no pneumonia cases (Table 1 and Figure 1).

| PDHS 2006-2007 n = 1590 | PDHS 2012-2013 n = 2142 | |

| Pneumonia | 1167 (73.3) | 1610 (75.1) |

| No pneumonia | 423 (26.7) | 532 (24.8) |

| Care seeking for ARI | ||

| Sought | 1108 (69.6) | 1707 (79.7) |

| Not sought | 482 (30.3) | 435 (20.3) |

The majority of ARI cases presented during 2006-2007 and 2012-2013 were infants aged 1 to 6 mo, i.e., 1213 (76.3%) and 1690 (78.9%) respectively followed by the neonates (< 1 mo). Additionally, male gender was predominantly affected as revealed from both the surveys (Table 2).

| PDHS 2006-2007 n = 1590 | PDHS 2012-2013 n = 2142 | |

| Age | ||

| Neonates (up to 28 d) | 377 (23.6) | 452 (21.0) |

| 1 to 6 mo | 1213 (76.3) | 1690 (78.9) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 877 (55.2) | 1143 (53.4) |

| Female | 713 (44.7) | 999 (46.5) |

According to the statistics, as majority of the cases of ARI are usually diagnosed as pneumonia, therefore further analysis of cases of pneumonia was conducted[17]. According to the DHS 2006-2007, mothers of younger age group (up to 20 years) were more likely (77.1%) to seek care for their child with pneumonia as compared to the other age groups, i.e., 66.9%. Whereas according to the DHS 2012-2013 the mothers aged up to 30 years were found more likely (82.0%) to seek care as compared to 77.3% of other age groups.

There was increase in healthcare seeking among the illiterate men and women in 2012-2013 as compared to 2006-2007. This rise in healthcare seeking observed among illiterate women was from 64% to 77% whereas that for men was from 59% to 77% between 2006-2007 to 2012-2013. However, the trend in educated caretakers remained static when the average of those with primary, secondary and above educational status was compared in both surveys. It was, however, found that of all the levels of education, those who were educated sought care with a higher proportion as compared to those illiterate.

In DHS 2006-2007 it was noted that the jobless fathers and the ones involved in unskilled work were less likely to seek health care, however, in the DHS survey 2012-2013 fathers’ occupation had no influence on variability of care seeking. Similarly, it was observed that health care seeking was increased among working women from 2006-2007 to 2012-2013 but was decreased among the non working women from 2006- 2007 to 2012-2013 as shown in Table 3.

| PDHS 2006-2007 | PDHS 2012-2013 | |||||

| Care seeking (n = 813) | No care seeking (n = 354) | P value | Care seeking (n = 1276) | No care seeking (n = 325) | P value | |

| Individual level factors | ||||||

| Maternal age (yr) | ||||||

| Up to 20 | 37 (77.1) | 11 (22.9) | 0.01 | 43 (75.4) | 14 (24.5) | 0.02 |

| 20 to 30 | 421 (71.5) | 167 (28.5) | 685 (82.0) | 150 (18.0) | ||

| 31 or above | 355 (66.9) | 176 (33.1) | 548 (77.3) | 161 (22.7) | ||

| Maternal education | ||||||

| Illiterate | 515 (64.2) | 287 (35.7) | < 0.001 | 700 (77.1) | 208 (22.9) | 0.007 |

| Primary | 136 (78.6) | 37 (21.4) | 221 (79.7) | 56 (20.2) | ||

| Secondary or above | 162 (84.4) | 30 (15.6) | 355 (85.3) | 61 (14.6) | ||

| Father’s education | ||||||

| Illiterate | 252 (59.5) | 171 (40.4) | < 0.001 | 390 (77.2) | 115 (22.7) | 0.004 |

| Primary | 151 (74.7) | 51 (25.2) | 182 (75.8) | 59 (24.2) | ||

| Secondary or above | 405 (75.7) | 130 (24.3) | 704 (82.5) | 151 (17.5) | ||

| Father’s occupation | ||||||

| Skilled manual | 149 (77.2) | 44 (22.8) | < 0.001 | 214 (84.2) | 40 (15.7) | 0.11 |

| Unskilled manual | 168 (65.3) | 89 (34.6) | 431 (78.1) | 121 (21.9) | ||

| Professional/ | 63 (72.4) | 24 (27.5) | 123 (78.8) | 33 (21.2) | ||

| technical | ||||||

| Agriculture related | 151 (62.1) | 92 (37.9) | 150 (81.1) | 35 (18.9) | ||

| Services/clerical | 253 (75.9) | 80 (24.1) | 319 (79.9) | 80 (20.1) | ||

| Did not work | 25 (50.0) | 25 (50.0) | 33 (70.2) | 14 (29.7) | ||

| Others | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | ||

| Maternal working status | ||||||

| Working | 182 (67.1) | 89 (32.8) | 0.3 | 247 (79.4) | 64 (20.6) | 0.46 |

| Not working | 631 (70.4) | 265 (29.5) | 1029 (80.1) | 261 (20.3) | ||

| Age of child (mo) | ||||||

| Neonates | 205 (74.2) | 71 (25.7) | 0.03 | 275 (81.1) | 170 (19.8) | 0.13 |

| 1 to 2 | 351 (71.8) | 138 (28.2) | 590 (81.3) | 135 (18.7) | ||

| 3-6 | 257 (64.0) | 145 (36.0) | 411 (76.5) | 126 (23.5) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 456 (70.7) | 189 (29.3) | 0.39 | 686 (80.1) | 170 (19.8) | 0.63 |

| Female | 357 (68.3) | 165 (31.6) | 590 (79.1) | 155 (20.8) | ||

| Place of delivery | ||||||

| Healthcare facility | 326 (76.7) | 99 (23.3) | < 0.001 | 683 (83.4) | 135 (16.6) | 0.008 |

| Home | 485 (65.5) | 255 (34.5) | 593 (75.7) | 190 (24.3) | ||

| Delivery conducted by | ||||||

| Health professional | 331 (79.0) | 88 (21.0) | < 0.001 | 672 (82.2) | 146 (17.9) | 0.01 |

| Trained birth attendant | 247 (71.1) | 100 (28.9) | 343 (79.5) | 89 (20.7) | ||

| Other untrained attendant | 229 (58.4) | 163 (41.6) | 261 (74.5) | 89 (25.4) | ||

| Delivery by cesarean section | ||||||

| Yes | 79 (82.2) | 17 (17.7) | < 0.001 | 169 (84.5) | 31 (15.5) | 0.19 |

| No | 734 (68.5) | 337 (31.4) | 1107 (79.1) | 293 (20.9) | ||

| Household level factors | ||||||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Lower class | 326 (60.2) | 216 (39.8) | < 0.001 | 524 (75.3) | 171 (24.7) | 0.005 |

| Middle class | 154 (69.3) | 68 (30.7) | 279 (82.3) | 60 (23.6) | ||

| Higher class | 333 (82.6) | 70 (17.4) | 473 (84.9) | 94 (15.1) | ||

| Community level factors | ||||||

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 287 (77.5) | 83 (22.5) | < 0.001 | 531 (82.1) | 116 (17.9) | 0.05 |

| Rural | 526 (66.0) | 271 (34.0) | 745 (78.1) | 209 (21.9) | ||

| Geographical region | ||||||

| Punjab | 321 (73.4) | 116 (26.5) | < 0.001 | 401 (87.3) | 58 (12.6) | < 0.001 |

| Sindh | 332 (78.8) | 89 (21.2) | 244 (82.4) | 52 (17.5) | ||

| KPK | 144 (51.4) | 136 (48.5) | 335 (70.9) | 137 (29.0) | ||

| Balochistan | 16 (55.1) | 13 (44.8) | 129 (72.8) | 48 (27.1) | ||

| Gilgit Baltistan | - | - | 114 (84.4) | 21 (15.6) | ||

| Islamabad (ICT) | - | - | 53 (85.4) | 9 (14.5) | ||

In 2006-2007, it was found that children delivered at healthcare facilities sought healthcare more than those delivered at home (76.7% vs 65.5%). Those who were delivered by health professionals also sought healthcare more as compared to those born by traditional birth attendants (79.0% vs 58.4%) and the ones delivered by c-section were more likely to seek care during an ARI episode as compared to ones delivered normally (82.2% vs 68.5%). The same findings were observed for data analyzed in 2012-2013 as shown in Table 3. When data of all these variables was compared between 2006-2007 and 2012-2013 it was found that there was a rise in seeking healthcare in 2012-2013 as shown in Table 3.

It was noted that from 2006-2007 to 2012-2013, there was a rise in care seeking among those in lower (60% vs 75%) and middle socioeconomic class (69% vs 82%) whereas that for the higher class remained almost static (82.4% vs 84.9%).

Similarly, caretakers living in urban areas as compared to rural (77.5% vs 66.0%) were more likely to seek care in 2006-2007 with a similar trend in 2012-2013 (82% vs 78%). However, it was noted that those living in rural communities improved care seeking from 2006-2007 to 2012-2013 (66% vs 78%).

It was found that the care seeking behavior improved among the caretakers belonging to the provinces of Punjab, Khyber Pakhtun Khwah (KPK) and Baluchistan in 2012-2013 as compared to 2006-2007. Additionally, it was found that is people living in Punjab and Sindh were more likely to seek care than those living in Balochistan and KPK provinces (73.4% and 78.8% vs 51.4% and 55.1% respectively) in 2006-2007. A similar trend was observed in 2012-2013 survey and details given in Table 3.

Our results show that there has been a significant improvement in health care seeking behavior among caretakers in some of the variables from 2006-2007 to 2012-2013. These included illiterate mothers and fathers, working caretakers, children who were born in the healthcare facilities, belonging to middle and lower socioeconomic class and those living in rural community.

The increase in the healthcare seeking among illiterate mothers and fathers could be attributed to two factors. One reason could be the increase in the migration of large proportion of rural population, the majority of which comprises of illiterate individuals, for higher employment and better healthcare opportunities[18]. Evidence suggests that urban residence provides better opportunities for healthcare seeking as indicated by a study conducted by Kugelman et al[18], who identified this difference in behavior among urban and rural communities. They indicated that individuals in rural communities had a lower weekly financial budget not only for healthcare but also for transport to a healthcare facility which led to delayed or no healthcare seeking[19]. Another study conducted in Bangladesh, whereby secondary data analysis of their DHS was conducted also revealed that urban population sought more care than rural one[20]. Another reason could be improvement of health management systems at the provincial level down to the level of the district and greater financial autonomy based on needs after devolution of the health ministry in 2011 whereby the autonomy for implementation of policies/programs was given to the provinces[21,22]. This benefitted the people in the form of quality healthcare delivery close to their doorstep[23]. This might also have led to increased health care seeking practice among the children who were born in health facilities[24].

Since the healthcare seeking behavior was found to be raised among the working women, it could be attributed to the provision of opportunity in terms of more fiscal space and awareness regarding utilization of health services. This points to improvement in woman’s autonomy which has been observed to more among working women[25]. Autonomy is defined as the woman’s ability to act freely and independently. With increase in both formal and informal employment among Pakistani women, they tend to make decisions based on their independent will[26]. This could be one of the major factors which might have contributed towards improved healthcare seeking among this group of women. This point is also reflected by decrease in healthcare seeking by non-working women. A study conducted in India on healthcare seeking behavior for antenatal care revealed that non-working women were less likely to seek healthcare as compared to working ones[27].

Results also show that there was a difference of healthcare seeking among the provinces with caretakers in Punjab and Sindh seeking more health care as compared to Balochistan and KPK. This could also be the result of the devolution due to which the provinces might be moving at a difference pace from each other in terms of implementation of the health programs[22]. It has been observed that the province of Punjab has been in the forefront due to their emphasis on the health as compared to the other provinces[22]. If there are some common factors, other provinces can learn from the experience of that province and improve the indicators however, due to geographical SEC and cultural and political variations should be taken into account while doing so.

It was also evident that when compared among the various socioeconomic classes in both surveys, healthcare seeking behavior was improved more in the lower and middle socioeconomic class as compared to the upper class. This again could be attributed to a change in the health systems which have become more accessible at the grass root level. In addition to that as the per capita income of the country has slightly improved therefore the individuals belonging to this class have shown this increase in healthcare seeking trend[25]. Another reason could increase in the educational level of the middle class women of the society which again points towards their autonomy as indicated earlier

In order to develop strategic policies and programs, it is important that information related to healthcare seeking behaviors and factors determining these behaviors are utilized. The socio demographic context of these behaviors is among the most impactful of all[28]. It is, therefore, important to develop strategies and interventions to promote appropriate and timely health care seeking behavior for children as in the absence of such interventions, there is a strong likelihood that there will further be an increase for the vulnerable population to suffer even more. Benefits of improving healthcare seeking are tremendous especially in settings where public health services are limited.

Based on these findings the following recommendations are made to influence policy and practice for improving care seeking for children with ARI: Educating the mothers especially in the rural communities and those of the older age group, on picking up the signs of ARI early through community based integrated programs; improving of quality of care and awareness so that care seeking is sought within 24 h of initiation of symptoms; more investment on infrastructure, by increasing the annual health budget, in the public sector making it accessible for the poor community which cannot afford the private sector; multi sectoral approach by enhancing and strengthening coordination among education, planning, health, and communication at the planning and implementation phases for example by developing safety net programs which could in turn improve the socioeconomic class of the community; More research on the consequences of delay in health care seeking practices and behavior, to decrease or prevent the high costs of illness.

The authors would like to acknowledge the team of Demographic Health Surveys to have provided access to the database for analysis including USAID and National Institute of Population Studies who has conducted the survey in Pakistan. Additionally, we would also like to acknowledge Mr Muhammad Afzal, Biostatician from Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Medical University for reviewing the data analysis and results.

Acute respiratory infections particularly pneumonia continue to be the leading killer in under five children in Pakistan, among other developing countries. Poor healthcare seeking practices are a major predisposing factor towards this. There is little evidence whereby trends of healthcare seeking for pneumonia have been assessed over a specific period of time. The authors have, therefore assessed the trends of healthcare seeking for pneumonia from data obtained from two consecutive demographic health surveys (DHS) (2006-2007 and 2012-2013) to determine any differences therein and to suggest suitable recommendations to improve the system.

It is important to determine trends in healthcare seeking for pneumonia patients to aid in development of effective innovative strategies. Demographic characteristics play an impactful role over healthcare seeking behavior which has not been assessed to that extent in Pakistan, let alone compared between various surveys.

This is the first study to have compared data between two consecutive DHS to assess healthcare seeking trends for children with pneumonia in Pakistan.

Healthcare seeking trends tend to affect the outcome of pneumonia. It is important for clinical practitioners to understand what factors are contributing to the fatal outcomes in terms of healthcare seeking so that they could undergo tailor made management of patients based on clinical findings. And this is the kind of information which this study has provided. Various strategies can be suggested for different categories of caretakers. Considering majority of cases did not seek healthcare due to lack of knowledge as indicated in this study, therefore illiterate mothers can be educated by developing and using validated standardized tools. Similarly, when a child is born in a facility the mother can be made aware of the potential diseases including pneumonia at the fist point of contact of the newborn to the physician. One suggestion could be the linking of these awareness sessions with the standardized immunization program whereby the caretaker’s knowledge is reinforced every time the child is immunized by the healthcare provider. Similarly, the vaccination cards could have printed pictorial messages indicating prevention and identification of the signs of pneumonia. If a patient comes from a poor socioeconomic class, the practitioners should counsel the caretakers upon the preventive measures of pneumonia development to avoid further episodes or new episodes in other children of the household. Additionally, those practitioners who are involved at the policy level should emphasize on development of effective strategies to cater to the factors which needs emphasis. Similarly, the results of this study indicate that there is a gap at the community level which can be filled by regular training of the Lady Health Workers who can manage the early signs and refer the patients for hospital care timely. This can in turn also assist in documentation of cases of ARI coming right from the community level which otherwise is identified through DHS based on recall.

The basic study is well designed and written.

| 1. | Colvin CJ, Smith HJ, Swartz A, Ahs JW, de Heer J, Opiyo N, Kim JC, Marraccini T, George A. Understanding careseeking for child illness in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and conceptual framework based on qualitative research of household recognition and response to child diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria. Soc Sci Med. 2013;86:66-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nair H, Simões EA, Rudan I, Gessner BD, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Zhang JS, Feikin DR, Mackenzie GA, Moïsi JC, Roca A. Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1380-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in RCA: 576] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Qazi S, Aboubaker S, MacLean R, Fontaine O, Mantel C, Goodman T, Young M, Henderson P, Cherian T. Ending preventable child deaths from pneumonia and diarrhoea by 2025. Development of the integrated Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhoea. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100 Suppl 1:S23-S28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | World Health Organization and UNICEF. Management of pneumonia in community settings; Joint statement by WHO and UNICEF. 2004; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/68926/1/WHO_FCH_CAH_04.06.pdf. |

| 5. | National Institute of Population Studies, Pakistan. Pakistan Demographic Health Survey 2012-13. 2013; Available from: http://www.nips.org.pk/abstract_files/Priliminary Report Final.pdf. |

| 6. | National Institute of Population Studies, Pakistan. Pakistan Demographic Health Survey 2006-07. 2008; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR200/FR200.pdf. |

| 7. | Gupta GR. Tackling pneumonia and diarrhoea: the deadliest diseases for the world’s poorest children. Lancet. 2012;379:2123-2124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | UNICEF. Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI). 2008; Available from: http://www.unicef.org/specialsession/about/sgreport-pdf/08_AcuteRespiratoryInfection_D7341Insert_English.pdf. |

| 9. | Geldsetzer P, Williams TC, Kirolos A, Mitchell S, Ratcliffe LA, Kohli-Lynch MK, Bischoff EJ, Cameron S, Campbell H. The recognition of and care seeking behaviour for childhood illness in developing countries: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sadruddin S, Khan IU, Bari A, Khan A, Ahmad I, Qazi SA. Effect of community mobilization on appropriate care seeking for pneumonia in Haripur, Pakistan. J Glob Health. 2015;5:010405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Reyes H, Perez-Cuevas R, Salmeron J, Tome P, Guiscafre H, Gutierrez G. Infant mortality due to acute respiratory infections: the influence of primary care processes. Health Policy Plan. 1997;12:214-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Syed U, Khadka N, Khan A, Wall S. Care-seeking practices in South Asia: using formative research to design program interventions to save newborn lives. J Perinatol. 2008;28 Suppl 2:S9-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tinuade O, Iyabo RA, Durotoye O. Health-care-seeking behaviour for childhood illnesses in a resource-poor setting. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46:238-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ogunlesi TA, Olanrewaju DM. Socio-demographic factors and appropriate health care-seeking behavior for childhood illnesses. J Trop Pediatr. 2010;56:379-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Quadri F, Nasrin D, Khan A, Bokhari T, Tikmani SS, Nisar MI, Bhatti Z, Kotloff K, Levine MM, Zaidi AK. Health care use patterns for diarrhea in children in low-income periurban communities of Karachi, Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:49-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Luque JS, Whiteford LM, Tobin GA. Maternal recognition and health care-seeking behavior for acute respiratory infection in children in a rural Ecuadorian county. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:287-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Walker CL, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, O’Brien KL, Campbell H, Black RE. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381:1405-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1417] [Cited by in RCA: 1553] [Article Influence: 119.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nishtar S. Devolving Health. 2011; Available from: http://www.heartfile.org/pdf/104_Devolving_health_Part2.pdf. |

| 19. | van der Hoeven M, Kruger A, Greeff M. Differences in health care seeking behaviour between rural and urban communities in South Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chowdhury RI, Islam MA, Gulshan J, Chakraborty N. Delivery complications and healthcare-seeking behaviour: the Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey, 1999-2000. Health Soc Care Community. 2007;15:254-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shaikh S, Naeem I, Nafees A, Zahidie A, Fatmi Z, Kazi A. Experience of devolution in district health system of Pakistan: perspectives regarding needed reforms. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:28-32. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Nishtar S. Healthcare Devolution. Pakistan Health Policy Forum. 2013; Available from: www.heartfile.org/blog/tag/healthcare-devolution. |

| 23. | Punjab Healthcare Commission. Minimum Service Delivery Standards (MSDS). 2013; Available from: http://www.phc.org.pk/catI_HCE.aspx. |

| 24. | Woldemicael G, Tenkorang EY. Women’s autonomy and maternal health-seeking behavior in Ethiopia. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:988-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ministry of Finance, Pakistan. Population, Labour Force and Employment.Pakistan Economic Survey.2013-2014. Ministry of Finance, Government of Pakistan. Available from: http://finance.gov.pk/survey/chapters_14/12_Population.pdf. |

| 26. | Navaneetham K, Dharmalingam A. Utilization of maternal health care services in Southern India. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1849-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shaikh BT, Hatcher J. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: challenging the policy makers. J Public Health (Oxf). 2005;27:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country of origin: Pakistan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Amornyotin S, Cebey-Lopez M, Moller T, Sundar S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ