Published online Feb 25, 2015. doi: 10.5495/wjcid.v5.i1.11

Peer-review started: August 23, 2014

First decision: October 5, 2014

Revised: November 18, 2014

Accepted: December 16, 2014

Article in press: December 17, 2014

Published online: February 25, 2015

Processing time: 166 Days and 23.5 Hours

Filariasis is a common health problem in tropical and subtropical regions including India. It commonly presents with lymphatic involvement in form of nonpitting pedal edema, chylous ascites, chyluria, hydrocele and lymphocele. Detection of microfilaria in ascitic fluid is an extremely uncommon finding. We present a case of non chylous ascites where microfilaria were detected in the ascitic fluid.

Core tip: We report a rare case of postpartum ascites caused by filarial infection. There are only a few case reports where microfilaria were detected in ascitic fluid; among these, non chylous ascitis is even rarer.

- Citation: Shah KS, Bhate PA, Solanke D, Pandey V, Ingle MA, Kane SV, Sawant P. Non chylous filarial ascites: A rare case report. World J Clin Infect Dis 2015; 5(1): 11-13

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3176/full/v5/i1/11.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5495/wjcid.v5.i1.11

Filarial infection is common in various Asian and African countries. It presents with various manifestations like ascites, pleural effusion and pedal edema; it may even be asymptomatic. We present an interesting and rare case of filariasis in ascitic fluid in postpartum female.

A 26 years old female residing in Uttar Pradesh, India, who was 2 mo postpartum, presented with chief complaints of abdominal pain and vomiting since 1 mo and abdominal distention since 15 d. The pain was in periumbilical, non radiating, dull, mild and continuous. It was associated with non-bilious vomiting, 2-3 episodes per day. She also complained of abdominal distention from the last 15 d, which was generalized and gradually increasing with increasing abdominal pain. She had undergone a Caesarean section 2 mo ago. The pregnancy had been uneventful. Her general physical, cardiovascular and respiratory systems examination did not reveal any abnormalities. Shifting dullness was present on abdominal examination without tenderness or hepatosplenomegaly.

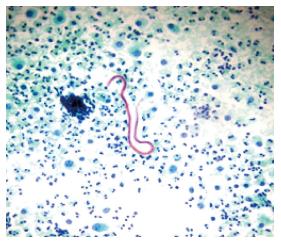

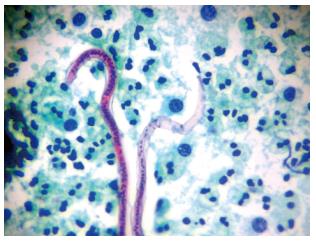

Laboratory examination revealed haemoglobin of 12.2 gm%, normal mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of 82fl, total leukocyte count of 16500/cmm and platelet count of 253000/cmm. Creatinine was 1.2 mg%, AST (aspartate aminotransferase) 21 IU/L, ALT (alanine aminotransferase) 25 IU/L and Bilirubin 1.1 mg/dL. Her total serum protein was 6.4 g/dL, albumin 3.7 g/dL and INR (international normalised ratio) 1.1, serum cholesterol and TG (triglycerides) were normal. Serum amylase was 45 IU/L and serum LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) was 1241 IU/L. Stool examination was normal. Ascitic fluid analysis revealed straw coloured fluid, total leukocyte count of 876 cells/mm3 with 65% neutrophils, ascitic protein 3.7 g/dL, ascitic albumin of 2.7 g/dL and SAAG was 1. Ascitic fluid ADA (adenosine deaminase) was 14 U/L, amylase 46 IU/L, LDH 106 IU/L, glucose 40 mg/dL and TG was 55 mg/dL. Ultrasonography of abdomen was unremarkable except for moderate ascites. Portosplenic Doppler was also normal. CT abdomen was suggestive of moderate ascites, omental and mesenteric fat stranding with multiple non necrotic mesenteric lymph nodes and diffuse long segment concentric wall thickening involving small bowel loops, especially the jejunum. Upper GI endoscopy was normal. She was given IV antibiotics and IV fluids. She improved symptomatically but abdominal distention persisted. Ascitic fluid cytology showed numerous eosinophils, few neutrophils, mesothelial cells and few histiocytes. Cytology was negative for malignant cells. But cytological examination revealed presence of sheathed microfilariae consistent with Wuchereria Bancrofti (Figures 1 and 2). Subsequently patient’s peripheral smear examination showed presence of motile microfilaria which confirmed our diagnosis (Figure 3). She was given diethylcarbamazine 300 mg/d for 21 d along with albendazole 400 mg/d for 7 d. She responded well to treatment; abdominal pain and ascites disappeared in a few days. Peripheral blood smear repeated after two weeks was negative for microfilaria.

We report a case of non chylous filarial ascites positive for microfilaria in ascitic fluid which is a rare finding. To the best of our knowledge, there are only two published cases where microfilaria were detected in ascitic fluid[1,2].

Filariasis is still endemic in many parts of world including India and a predominant cause of health morbidity. It is quite prevalent in many states of India like Jharkhand, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Orissa, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Bihar. Many infected patients remain asymptomatic.

The definitive host for filarial infection is man. The parasites have a predilection for lymphatics. The Culex mosquito is an intermediate vector. They ingest microfilariae from affected individuals and this larvae develop into active motile forms in 10-12 d for further transmission into a new host. In the definitive host, the larvae develop into adult worms in lymphatics and give rise up to 50000 worms/d.

The adult worm usually resides in lymphatics while microfilariae traverse in peripheral blood. Microfilaria are visible in specimens of tissue or fluids due to obstruction of lymphatics and vascular channels. Inflammatory conditions, major trauma, even stasis or tumours can precipitate obstruction. Due to this obstruction, there is lymphatic damage and extravasation of microfilariae. Based on the detection of microfilariae in blood samples and body fluids, we establish our diagnosis. On autopsy, adult filarial parasites can be demonstrated.

Moreover, pregnancy is associated with pelvic congestion due to effect of progesterone and other placental hormones. Hypothetically, caesarean section could be a cause of traumatic rupture of lymphatic vessel with subsequent spread of microfilariae into the peritoneal cavity[3].

Ascites and pleural effusion are uncommon findings. Commonly they are chylous in nature due to blockage of lymph from the occluded lymphatic channels. Such microfilarial ascites being non-chylous microfilarial ascites is extremely rare. Lymphangitis because of partial obstruction is a proposed mechanism for such exudative collection[4]. Ascitic fluid TG could also be low due to inadequate diet, but ascitic fluid TG content is low in our patient inspite of adequate food intake.

Many authors have reported microfilariae in breast lump as well as in lymph node aspirates[5,6]. Microfilariae have been detected in thyroid swelling and rarely in subcutaneous swellings[7,8]. Detection of microfilaria in body fluids like pleural effusion and ascites is rare and such ascites being non chylous is extremely rare.

Therefore clinical suspicion and careful cytological examination is extremely important to avoid misdiagnosis. Demonstration of parasite in cytology will be helpful not only in the right diagnosis but also in instituting specific treatment.

Vomiting since 1 mo and abdominal distention since 15 d.

Ascites on percussion of abdomen without organomegaly.

Twenty six years old female 2 mo postpartum presented with complaints of abdominal pain and Vomiting since 1 mo and abdominal distention since 15 d. Budd chiari syndrome, decompensated chronic liver disease, tuberculosis.

Normal CBC, liver function and metabolic panel except high leukocyte count with ascitic fluid showing high leukocytes with low protein and normal ADA level.

CT abdomen was done which was suggestive of moderate ascites, omental and mesenteric fat stranding with multiple non necrotic mesenteric lymph nodes and diffuse long segment concentric wall thickening involving small bowel loops especially jejunum with normal ultrasound and colour Doppler study.

Ascitic cytology revealed presence of numerous neutrophils with presence of microfilaria of W Bancrofti.

Patient was treated with diethylcarbamazine for 21 d and albendazole for 7 d.

Presence of microfilaria has been documented in atypical location by FNA has been documented by Yenkeshwar PN and others but detection of microfilaria in ascitic fluid is very uncommon.

Clinical suspicion and careful cytological examination by expert pathologist is extremely important in clinical practice.

Shah and colleagues present an interesting and very rare case of ascites due to filariasis in a young woman a few weeks after giving birth.

| 1. | Yenkeshwar PN, Kumbhalkar DT, Bobhate SK. Microfilariae in fine needle aspirates: a report of 22 cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006;49:365-369. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mitra SK, Mishra RK, Verma P. Cytological diagnosis of microfilariae in filariasis endemic areas of eastern Uttar Pradesh. J Cytol. 2009;26:11-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Babic I, Tulbah M, Ghourab S. Spontaneous resolution of chylous ascites following delivery: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Walter A, Krishnaswami H, Cariappa A. Microfilariae of Wuchereria bancrofti in cytologic smears. Acta Cytol. 1983;27:432-436. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Varghese R, Raghuveer CV, Pai MR, Bansal R. Microfilariae in cytologic smears: a report of six cases. Acta Cytol. 1996;40:299-301. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pandit AA, Shah RK, Shenoy SG. Adult filarial worm in a fine needle aspirate of a soft tissue swelling. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:944-946. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Joshi AM, Pangarkar MA, Ballal MM. Adult female Wuchereria bancrofti nematode in a fine needle aspirate of the lymph node. Acta Cytol. 1995;39:138. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Dey P, Walker R. Microfilariae in a fine needle aspirate from a skin nodule. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:114. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer: Lutz P S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/