Published online Jan 15, 2021. doi: 10.5495/wjcid.v11.i1.19

Peer-review started: August 7, 2020

First decision: September 21, 2020

Revised: October 19, 2020

Accepted: October 26, 2020

Article in press: October 26, 2020

Published online: January 15, 2021

Processing time: 152 Days and 18.7 Hours

Reports of leishmaniasis are scarce in North America. It is considered to be one of the neglected tropical diseases. It is seen in immigrants from endemic areas to United States. Treatments are not readily available in the United States. Untreated or inadequately treated cutaneous leishmaniasis not only causes localized disfigurement but can advance to more permanent and devastating mucosal disfigurement and perforation, if caused by a species that can also cause mucocutaneous leishmaniasis.

A 42-year-old human immunodeficiency virus negative male immigrant from Honduras presented to the emergency department of our facility in Louisiana with a 2-mo history of a left lower extremity ulcer. It started as a painless blister that progressed in size and developed into other smaller lesions tracking up the thigh and became tender and erythematous. Clinically looked nontoxic and healthy. He was afebrile. Blood tests, except inflammatory markers, were within normal limits. The cellulitis of the leg was treated with 6 d of vancomycin that also relieved the pain. Skin biopsy was obtained, and histopathology was suspicious for leishmania. Polymerase chain reaction/deoxyribonucleic acid sequencing done by centers for disease control and prevention confirmed the diagnosis as Leishmania panamensis. There was no involvement of naso-oropharyngeal mucosa, confirmed by otolaryngology. The patient was treated with miltefosine for 28 d. Clinic follow-up after approximately 11 mo revealed a healed skin ulcer.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis should be in the differential diagnosis of skin ulcers of travelers from endemic areas. Awareness regarding diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis needs to be enhanced.

Core Tip: This case highlights the importance of prompt and accurate diagnosis, and appropriate treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis to prevent further complications and advancement to mucosal form. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of skin lesions with appropriate epidemiologic context. Oral therapy with miltefosine is available for use as in this case. It is important to evaluate for human immune-deficiency virus disease since presentation and complications in immunosuppressed individuals can be more severe.

- Citation: Azhar A, Connell HE, Haas C, Surla J, Reed D, Kamboj S, Love GL, Bennani Y. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Louisiana - one-year follow-up: A case report. World J Clin Infect Dis 2021; 11(1): 19-26

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3176/full/v11/i1/19.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5495/wjcid.v11.i1.19

Leishmaniasis is one of the neglected tropical diseases as per World Health Organization (WHO)[1]. Leishmaniasis is a vector-borne zoonotic disease which is caused by intracellular flagellated protozoans of the genus Leishmania. These are transmitted to the humans or other animals by the bite of infected female phlebotomine sand flies during blood feeding[2,3]. The disease is widespread in the tropical and subtropical areas. Per WHO, it is estimated that between 700000 to 1.0 million people are newly infected every year with leishmaniasis[4].

The disease has three main forms[4-6]. Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is the most common form and can be localized or diffuse. Though it causes various types of skin lesions[7-9], it typically manifests as ulcers. The ulcers are usually well-defined, with raised edges and a reddish base (referred to as volcano-like or pizza-like ulcers), leading to permanent scarring and serious disability. Visceral leishmaniasis (Kala-azar), the most serious form, is fatal in more than 95% of cases if left untreated and includes irregular bouts of fever, bone marrow involvement and hepato-splenomegaly. Some species of CL if not treated can lead to mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (Espundia), which can cause devastating destruction of the nasopharyngeal mucous membranes. We present a case of CL with subgenus Viannia and species panamensis [L. (V.) panamensis].

“Skin lesion on left lower leg for last 2 mo, now with small “lumps and bumps” tracking up my thigh with discomfort.”

A 42-year-old male who immigrated from Honduras to the United States approximately 2 mo before presenting to our facility’s emergency department in Louisiana. He reported 2 mo ago he was climbing mountains and cutting wood with his friends in Honduras when he felt a bite on his left lower leg. A few weeks later, he developed a blister at the site. Over the next 2 mo period, the lesion started to necrose and enlarge. Approximately 5-10 d prior to this presentation he started to see “lumps and bumps” on his leg tracking up from the wound to his thigh, with mild discomfort in his thigh. Prior to this presentation, the lesions were non-tender.

He denied any trauma, dog or cat bite, swimming in fresh or salt water, any thorn prick or gardening, fishing, seafood use. He denied any history of immuno-compromise.

Review of systems: Positives: Skin: wound and tender nodules on leg; Negatives: (1): Constitutional: No fevers/chills, no weight loss; (2) Cardiac: No palpitations, no chest pain, no dyspnea, no edema; (3) Pulmonary: No shortness of breath, no cough, no hemoptysis; (4) Gastrointestinal: No nausea, vomiting or diarrhea; and (5) Genitourinary: No urinary symptoms.

Patient reported no known past medical or surgical history.

Nonsmoker, no alcohol or illicit drug use history. No history of diabetes, and no history of immunosuppression in either the patient or in family members.

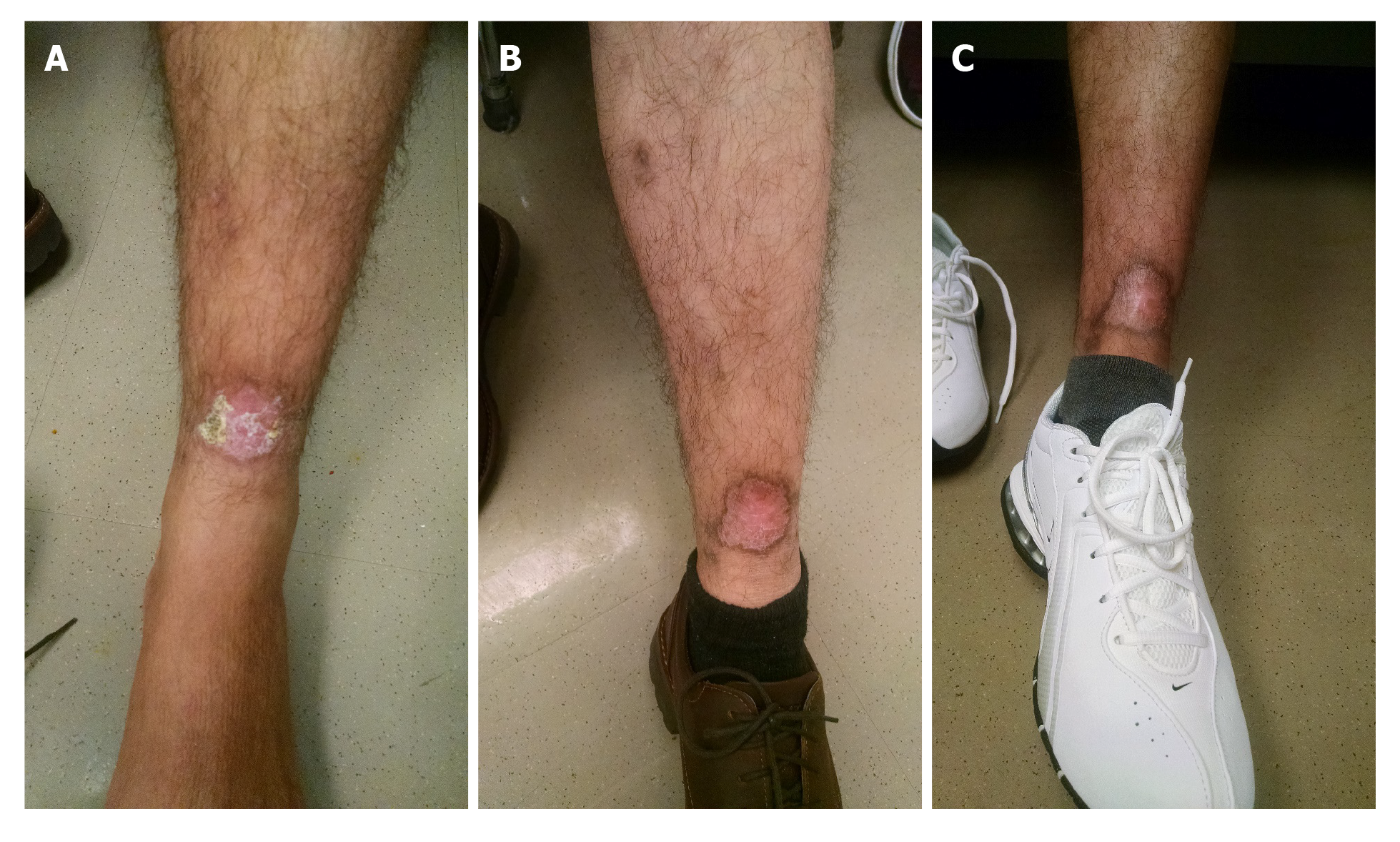

On presentation to the emergency department, patient was afebrile with temperature of 98 °F, heart rate 86 beats/min, respiratory rate 16 per min, blood pressure 127/79 mmHg and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. His body mass index was 25 kg/m2. He appeared clinically non-toxic and healthy. Nasal and oral examination was benign with no lesions or perforation noted. Abdominal examination did not reveal any tenderness or hepato-splenomegaly. There was an approximately 3 cm × 3 cm left lower extremity wound on the anterior tibial area, with some erythema in the surrounding area. There were tracking tender nodules from the wound up to his thigh, with indurated skin with mild tenderness on the thigh and on the nodules (Figure 1A).

Blood counts were within normal limits with white blood cell count 9.7 (4.5 × 103/μL-11 × 103/μL), Hemoglobin 13.7 (13.5-17.5 g/dL), platelet count 254 (130 × 103/μL-400 × 103/μL). Chemistry revealed normal sodium, potassium, chloride and glucose levels with creatinine 0.82 (0.7-1.4 mg/dL), normal transaminases and lactic acid level. Inflammatory markers were elevated with C reactive protein of 2.5 (normal less than 0.9 mg/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 45 (normal 0-15 mm/h). Later in the hospital course, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was ruled out by a 4th generation HIV antibody/antigen test.

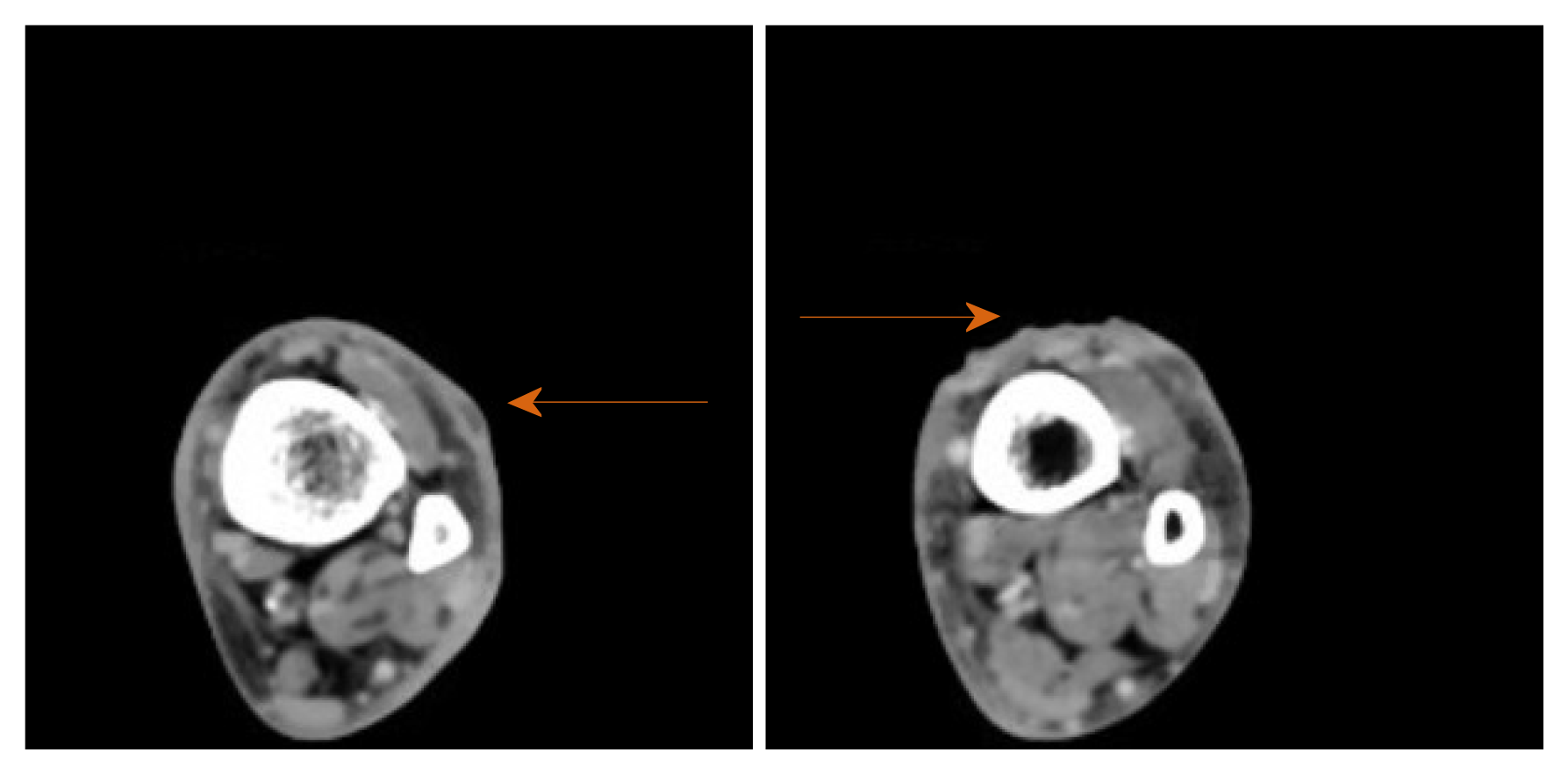

Plain X-rays of the ankle and tibia-fibula were normal. Venous doppler ultrasound of the lower extremity ruled out thrombosis. Computer tomography scan of the extremity with intravenous (IV) contrast revealed lymphadenopathy at left popliteal and left groin area. Small fluid collections or phlegmons at the nodules and ulceration sites were present (Figure 2).

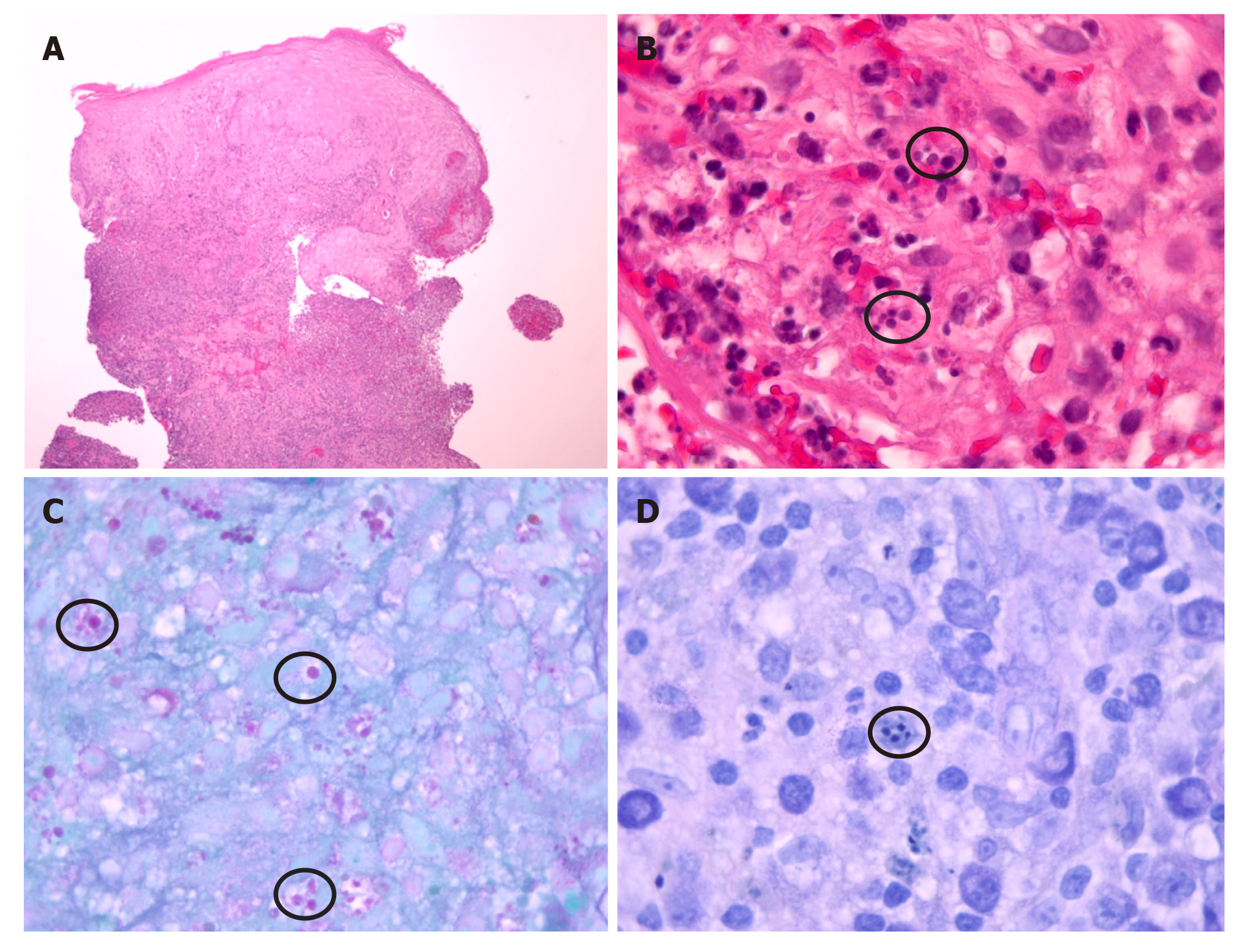

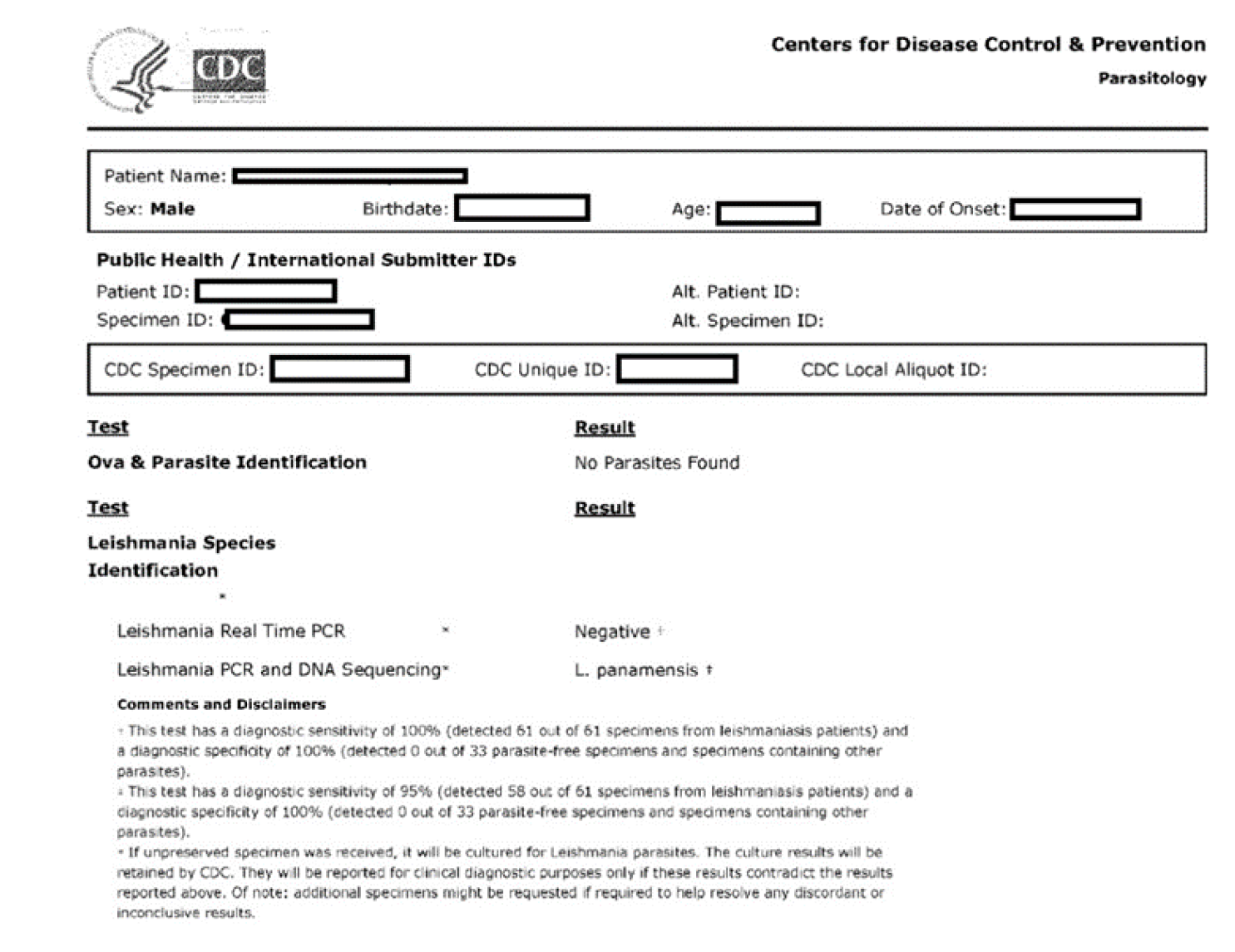

Intravenous vancomycin was started for the leg cellulitis. Our suspicion was high for leishmaniasis because of his history of recently living in an endemic area, having a known insect bite, and friends with similar histories in Honduras being diagnosed with CL. He was evaluated by dermatology, who obtained a skin punch biopsy per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations. Tissue was sent to our hospital laboratory and to the state public health laboratory where it was shipped to CDC. The results from our laboratory revealed negative bacterial, fungal and acid-fast bacilli cultures and stains. Histopathology was compatible with leishmaniasis amastigotes (Figure 3).

CL with sporotrichoid lymphangitis with cellulitis of the leg. After 6 d, IV vancomycin was stopped after resolution of the cellulitis and leg tenderness (Figure 1B and C). Final diagnosis was reported as Leishmania panamensis that was confirmed through polymerase chain reaction (PCR)/deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequencing by CDC (Figure 4).

CL with Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis.

As per CDC recommendations, otolaryngology consultants performed flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy/nasopharyngoscopy and confirmed no mucosal involvement. The patient was treated with miltefosine 50 mg PO three times daily for 28 d.

Patient followed up with dermatology and infectious diseases clinic at several occasions, and then visited at approximately 11 mo with a healed ulcer (Figure 5).

About 95% of CL cases occur in the Americas, the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East and Central Asia. According to WHO, in 2018, over 85% of new CL cases occurred in 10 countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia. It is estimated that between 600000 to 1 million new cases of CL occur worldwide annually[4]. Reports of leishmaniasis are scarce in North America. In the United States, it is seen in travelers from endemic areas. CL has also been reported in American military personnel returning home from assignments in Iraq and Afghanistan[10]. Usually CL skin lesions are painless. But if painful, there is generally an indication to treat it also as a bacterial superinfection. In our patient, the lesions were painful initially, but the pain subsided after treating the cellulitis. CL typically presents with skin lesions after an incubation period of 2 wk to 6-8 mo. There has been one reported case of CL with Leishmania panamensis with incubation period as long as 18 mo, that was successfully treated with IV amphotericin. This patient was also from Honduras and had atypical multiple lesions[9]. A sporotrichoid-like pattern of skin lesions is not typical of CL but has been seen in various other case reports in addition to our patient[11-13]. The case report published recently by Mann et al[13], discusses about a couple that traveled from Costa Rica. The husband had sporotrichoid like pattern of skin lesions.

In immunocompromised patients such as those with HIV, the disease course can be worse. Chances of reactivation is possible with decreased immunity[14].

Diagnosis starts with obtaining a good history taking, including travel history, and a detailed physical examination. It is confirmed with biopsy of a skin lesion, ideally the active part of the lesion at the edge. Typical microscopic findings are mixed in-flammatory infiltrate with many histiocytes and granuloma formation containing amastigotes[15]. But atypical microscopic findings such as tuberculoid granulomatous processes has also been identified without organisms seen in some reports[16]. Sensitivity of histopathologic examination in diagnosing CL is low, perhaps only 14%–18%[17]. The use of multiple diagnostic modalities including PCR and DNA sequencing helps confirm the diagnosis as well as provides speciation, useful to its management[18,19], like in our case also.

Extensive guidelines regarding diagnosis and treatment have been created by professional medical societies[20]. The pentavalent antimonials have been considered the mainstay treatment for CL in most parts of the world except in North America, where they are not readily available[20]. Our patient’s friends who had similar presentations in Honduras reportedly did respond to pentavalent antimonials, per his report. Topical paromomycin and parental amphotericin have also been used. Resistance against amphotericin and antimonials have been reported[21,22].

Miltefosine is thus far the only oral drug reported that can be used for all three types of leishmaniasis including in cases with HIV[23,24]. Miltefosine belongs to the class of alkyl phosphocholine drugs. It has shown antileishmanial activity, linking its activity mainly to apoptosis and disturbance of lipid-dependent cell signaling pathways[23]. Patients on treatment should be monitored for elevations in transaminases and serum creatinine. It should not be given to pregnant patients[23,24]. The recommended duration of therapy is 28 d, but longer duration of therapy has also been given as mentioned by Mann et al[13] where they offered 56 d therapy.

Like other reported cases[11,13,25], our case was also successfully treated with miltefosine (Figure 5). He was following with the corresponding author in the outpatient setting for approximately 11 mo as of the time of this submission. Our patient had no adverse events during treatment with miltefosine.

Though leishmaniasis is not common in North America, clinicians should be aware of it and include it in the differential diagnoses of skin lesions in patients who have traveled from endemic areas. Optimal therapy of CL is vital to prevent progression into mucosal form. As of today, there are no available preventive or therapeutic vaccines. The most effective way to prevent infection is avoiding sand fly bites by adopting controlled measures.

We acknowledge Louisiana State University dermatology, New Orleans for obtaining the diagnostic biopsy. We also thank CDC, and the microbiology and pathology laboratories at University Medical Center New Orleans.

| 1. | World Health Organization. Integrating neglected tropical diseases into global health and development: fourth WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/resources/9789241565448/en/. |

| 2. | Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, Jannin J, den Boer M; WHO Leishmaniasis Control Team. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3243] [Cited by in RCA: 3747] [Article Influence: 267.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Maroli M, Feliciangeli MD, Bichaud L, Charrel RN, Gradoni L. Phlebotomine sandflies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Med Vet Entomol. 2013;27:123-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 44.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization Fact Sheet. [Updated 2 March 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/Leishmaniasis. |

| 5. | Alhumidi AA. Skin pseudolymphoma caused by cutaneous leismaniasia. Saudi Med J. 2013;34:537-538. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Shah S, Shah A, Prajapati S, Bilimoria F. Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in HIV-positive patients: A study of two cases. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2010;31:42-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Meireles CB, Maia LC, Soares GC, Teodoro IPP, Gadelha MDSV, da Silva CGL, de Lima MAP. Atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;172:240-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Neitzke-Abreu HC, Venazzi MS, de Lima Scodro RB, Zanzarini PD, da Silva Fernandes AC, Aristides SM, Silveira TG, Lonardoni MV. Cutaneous leishmaniasis with atypical clinical manifestations: Case report. IDCases. 2014;1:60-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gogol-Tagliaferro A, Swender D, Chernin L, Tcheurekdjian H, Meyerson H, Hostoffer R. A prolonged incubation period in zosteriform Leishmania panamensis. Cutis. 2014;93:E5-E6. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Aronson NE, Sanders JW, Moran KA. In harm's way: infections in deployed American military forces. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1045-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ismailjee SB, Bernstein JM, Burdette SD. Bite the hand that sprays you. Skinmed. 2006;5:296-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pavlidakey PG, Huynh T, McKay KM, Sami N. Leishmaniasis Panamensis Masquerading as Myiasis and Sporotrichosis: A Clinical Pitfall. Case Rep Pathol. 2015;2015:949670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mann S, Phupitakphol T, Davis B, Newman S, Suarez JA, Henao-Martínez A, Franco-Paredes C. Case Report: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis due to Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis in Two Travelers Successfully Treated with Miltefosine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:1081-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Alvar J, Aparicio P, Aseffa A, Den Boer M, Cañavate C, Dedet JP, Gradoni L, Ter Horst R, López-Vélez R, Moreno J. The relationship between leishmaniasis and AIDS: the second 10 years. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:334-359, table of contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 593] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | David CV, Craft N. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:491-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Miller DD, Gilchrest BA, Garg A, Goldberg LJ, Bhawan J. Acute New World cutaneous leishmaniasis presenting as tuberculoid granulomatous dermatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:361-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Antinori S, Gianelli E, Calattini S, Longhi E, Gramiccia M, Corbellino M. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an increasing threat for travellers. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:343-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Reithinger R, Dujardin JC, Louzir H, Pirmez C, Alexander B, Brooker S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:581-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 890] [Cited by in RCA: 997] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | González U, Pinart M, Reveiz L, Alvar J. Interventions for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD005067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, Pearson R, Lopez-Velez R, Weina P, Carvalho EM, Ephros M, Jeronimo S, Magill A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Leishmaniasis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e202-e264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1105] [Cited by in RCA: 1186] [Article Influence: 59.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ponte-Sucre A, Gamarro F, Dujardin JC, Barrett MP, López-Vélez R, García-Hernández R, Pountain AW, Mwenechanya R, Papadopoulou B. Drug resistance and treatment failure in leishmaniasis: A 21st century challenge. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0006052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 645] [Article Influence: 71.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dorlo TP, Balasegaram M, Beijnen JH, de Vries PJ. Miltefosine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of leishmaniasis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2576-2597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Soto J, Soto P. Miltefosine: oral treatment of leishmaniasis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006;4:177-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Poeppl W, Walochnik J, Pustelnik T, Auer H, Mooseder G. Cutaneous leishmaniasis after travel to Cyprus and successful treatment with miltefosine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:562-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Infectious Diseases

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chiu KW, Firooz A, Song G, Wang W S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LYT