Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.114554

Revised: October 1, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 87 Days and 22 Hours

Clinical hypnosis has been proposed as a non-pharmacological intervention in pediatric healthcare, drawing on children’s natural capacity for imagination and focused attention. It has been applied across a broad spectrum of medical and psychological conditions, yet its true clinical value remains a matter of debate. This narrative review synthesizes findings from randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, systematic reviews, and clinical case series on pediatric hypno

Core Tip: Clinical hypnosis has emerged as a developmentally appropriate, non-pharmacological tool with potential applications across pediatric medicine. Evidence suggests benefits in acute and chronic pain, functional gastrointestinal disorders, anxiety, habit disorders, and supportive care in chronic illness. By engaging children’s imagination and suggestibility, hypnotherapy may promote self-regulation, reduce symptom burden, and improve quality of life. However, the evidence base remains uneven—strong in some domains but limited or preliminary in others. Misconceptions, limited training op

- Citation: Al-Beltagi M. Clinical hypnosis in pediatric care: An adjunctive tool or therapeutic illusion. World J Exp Med 2025; 15(4): 114554

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v15/i4/114554.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.114554

Clinical hypnosis is a focused therapeutic technique that harnesses guided attention, vivid imagery, and positive su

| Aspect | Clinical hypnosis | Stage hypnosis |

| Primary purpose | Therapeutic: To facilitate healing and positive change for psychological, medical, or behavioral conditions (e.g., anxiety, pain, phobias) | Entertainment: To amuse, impress, and entertain an audience by showcasing unusual hypnotic phenomena |

| Guiding intent | Client-centered: The entire process is designed for the well-being, benefit, and empowerment of the individual client | Audience-centered: The process is designed to be dramatic, funny, and engaging for the people watching the show |

| Setting | Private & confidential: A professional clinical environment (e.g., hospital, therapy office, private practice) | Public & performative: A public stage, performance venue, or social gathering |

| Practitioner | Licensed healthcare professional: A trained and licensed professional (e.g., psychologist, physician, dentist, clinical social worker) with specific certification in hypnotherapy | Performer/entertainer: Often a charismatic performer with training in showmanship and rapid induction techniques, but typically without formal healthcare or psychological credentials |

| Training & certification | Rigorous & accredited: Requires graduate-level healthcare education followed by specialized, accredited training and certification from professional boards (e.g., ASCH, SCEH) | Unregulated: Training varies widely from mentorships to private courses. There are no formal, universally recognized educational or licensing standards |

| Ethical oversight | Strictly governed: Bound by the ethical codes and legal statutes of their respective healthcare professions (e.g., confidentiality, "do no harm") | No Formal governance: Lacks formal ethical oversight. The primary "rule" is to put on a good show, though responsible performers avoid outright harm |

| Subject selection | Client-initiated: Individuals actively seek therapy for a specific problem. Suitability is assessed, but the primary goal is to help the individual seeking treatment | Volunteer-based & screened: Participants are volunteers from the audience, often implicitly or explicitly screened for high suggestibility and extroversion to ensure compliance and a good performance |

| Consent | Informed & specific: A formal process where the client understands the therapeutic goals, methods, potential risks, and benefits, and gives explicit consent for treatment | General & implied: Volunteers agree to be on stage but may not fully understand what will be asked of them. Consent is often influenced by peer pressure and the desire to be part of the show |

| Techniques used | Individualized & evidence-based: Techniques are carefully selected and tailored to the client's specific needs, personality, and therapeutic goals | Standardized & rapid: Uses fast, authoritarian induction methods designed for maximum effect on a group in a short amount of time. The focus is on creating observable behaviors |

| Client safety & dignity | Paramount concern: Protecting the client's physical and emotional safety and dignity is the highest priority. Confidentiality is legally required | Secondary to entertainment: While most performers avoid true danger, participants may be put in embarrassing or undignified situations for comedic effect. There is no expectation of privacy |

| Duration of effect | Designed for long-term change: Aims to create lasting changes in perception, behavior, or symptom management that persist long after the session ends | Transient & short-lived: Effects are intended to last only for the duration of the show. Suggestions are typically removed before the participant leaves the stage |

| Documentation & follow-up | Standard practice: Sessions are meticulously documented in the client's confidential medical record. Follow-up is integral to assessing progress and adjusting treatment | None: No documentation, record-keeping, or follow-up care is provided to participants |

| Examples of use | Pain management (chronic pain, childbirth, surgery), anxiety reduction, habit control (e.g., smoking cessation), phobia treatment, PTSD symptom management | Making participants forget their names, believe they are a celebrity, dance uncontrollably, or react to absurd suggestions for the audience's amusement |

The application of hypnosis in pediatric populations has a rich history, with its roots tracing back over a century to early reports of its use in pain management, surgical preparation, and behavior modification. Hypnosis gained further credibility in the mid-20th century, with growing clinical observations and research highlighting its effectiveness in children[3]. Children, due to their imaginative minds, natural suggestibility, and often reduced psychological resistance, are particularly receptive to hypnotic techniques. Despite these promising attributes, hypnosis largely remained a niche approach until recent years, when the rise of integrative medicine sparked renewed interest in its potential[4].

Modern pediatric care increasingly emphasizes non-invasive, non-pharmacological interventions, driven by concerns about medication overuse, potential side effects, and the overarching need for more holistic patient care. Clinical hypnosis aligns perfectly with this evolving paradigm, offering a safe and adaptable adjunct to conventional treatments across various domains, including procedural pain, anxiety, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, and behavioral conditions. As healthcare systems continue to prioritize patient-centered approaches and psychological well-being, hypnosis is emerging as a therapeutic tool in the pediatric arsenal[5]. However, despite growing enthusiasm, the clinical evidence remains uneven, and questions persist regarding its true therapeutic efficacy.

The relevance of hypnosis in child health is more pronounced now than ever. Children grappling with chronic illness, challenging medical procedures, or significant psychological distress require management strategies that are both effective and empowering[6]. Hypnosis not only offers symptom relief but also equips children with crucial self-re

This comprehensive review aims to critically evaluate the role of clinical hypnosis in pediatric healthcare. It examines the underlying neurocognitive mechanisms, surveys its diverse clinical applications across a wide range of pediatric conditions, and highlights both its potential advantages and its current limitations compared to conventional treatments. By synthesizing the available evidence and identifying gaps in knowledge, training, and accessibility, this review seeks to inform pediatricians, child psychologists, and allied health professionals about the promise-and the uncertainties-of hypnotherapy. Ultimately, it emphasizes the need for cautious, evidence-based integration of hypnosis into pediatric care while outlining priorities for future research and clinical practice.

We conducted this review through a narrative synthesis of the existing literature on pediatric clinical hypnosis, using a comprehensive search of electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, for studies published in English up to August 2025. Search terms combined keywords such as “pediatric hypnosis”, “clinical hypnotherapy”, “children”, “adolescents”, “pain management”, “functional disorders”, “anxiety”, and “non-pharmacological therapy”. Both randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, systematic reviews, and relevant case series were considered. Reference lists of key papers were also manually screened to identify additional studies. Studies focusing exclusively on adult populations were not included except where a brief reference was necessary to contextualize pediatric findings. Because this is a narrative review, no formal quality assessment tool was applied; instead, emphasis was placed on peer-reviewed studies with clear methodology, adequate sample sizes, and clinical relevance. This approach ensured a broad yet clinically focused synthesis, while acknowledging that methodological diversity may limit direct comparisons between studies.

Clinical hypnosis is a unique and dynamic state of focused attention and increased suggestibility, accompanied by reduced peripheral awareness and a heightened responsiveness to therapeutic guidance. Figure 1 shows the core components of clinical hypnosis. Crucially, this is not a state of unconsciousness or sleep, but a distinct neurocognitive condition that involves both biological and psychological modulation. Advances in functional neuroimaging have significantly clarified the neural mechanisms underlying hypnosis, revealing consistent changes in brain activity, connectivity, and neurochemical signaling[8].

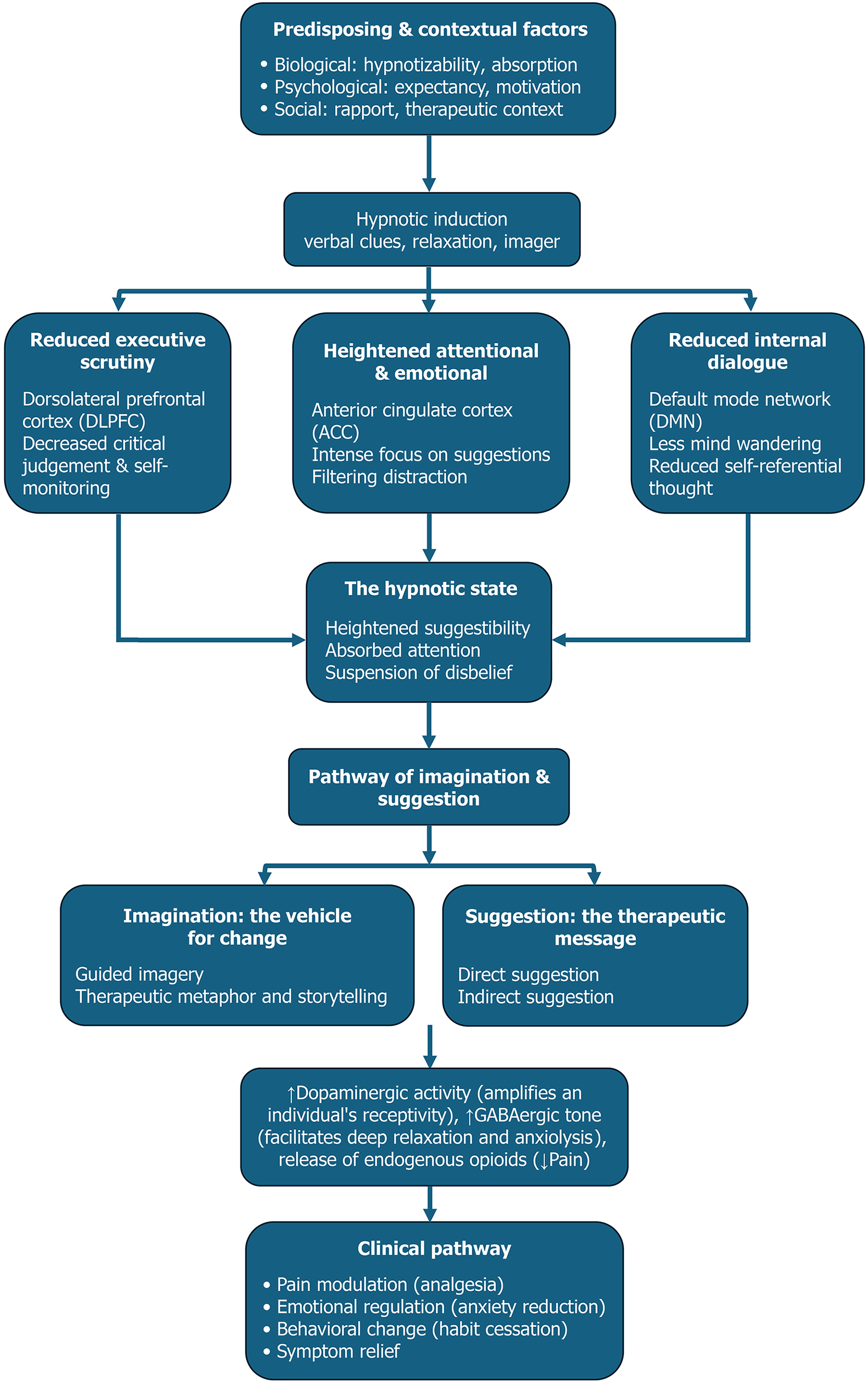

At the core of the hypnotic state lies a functional reorganization of brain networks. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)-a region essential for attention control, emotional regulation, and conflict monitoring-is consistently activated during hypnosis. In contrast, there is a reduction in the activity or functional connectivity of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which typically governs executive control and critical evaluation. This decoupling helps explain why individuals under hypnosis become less constrained by rational filtering and more open to therapeutic suggestion[9]. Additionally, hypnosis is associated with a downregulation of the default mode network, which is responsible for self-referential thought and mind-wandering, fostering a deep immersion in the therapeutic experience. These shifts align closely with patients’ subjective reports of narrowed focus, heightened absorption, and diminished internal distraction-especially beneficial in children with shorter attention spans[10].

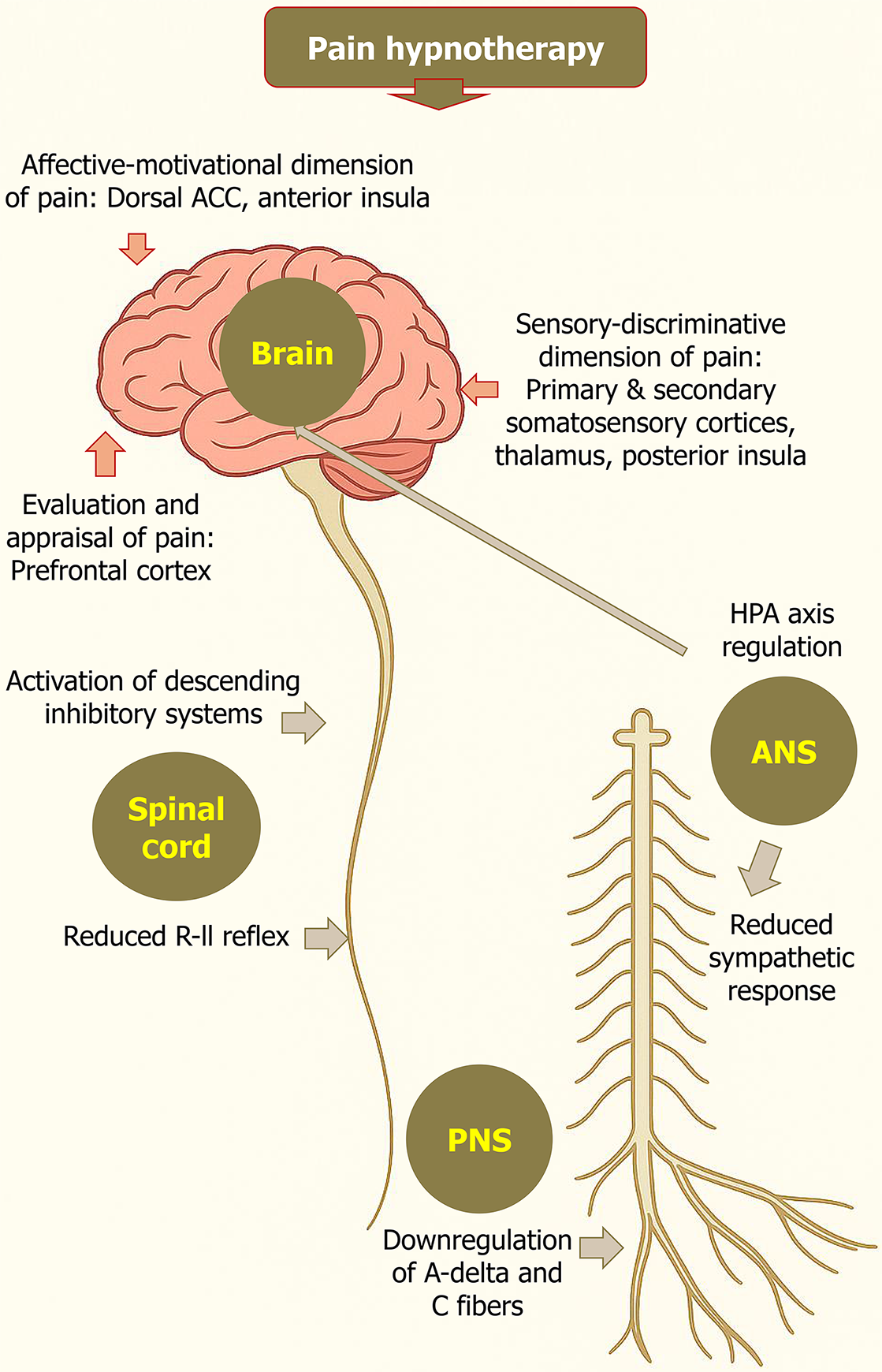

Hypnosis also exerts multi-level effects on pain processing. At the cortical level, it alters the sensory-discriminative aspects of pain via the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices, the thalamus, and the posterior insula. The emotional-motivational dimension of pain is modulated through the anterior insula and dorsal ACC, while cognitive appraisal and re-framing of pain occur in the prefrontal cortex[11]. Hypnosis can also influence pain transmission at the spinal level by activating descending inhibitory pathways and reducing the R-III reflex-a spinal marker of nociception[12]. Moreover, it affects the autonomic nervous system by decreasing sympathetic tone and modulating the hypotha

On a neurochemical level, hypnosis appears to modulate key neurotransmitter systems. Dopaminergic activity, particularly in the striatum, is enhanced-supporting motivation, attention, and reward processing, all of which increase receptivity to suggestion. GABAergic tone is thought to increase during hypnosis, facilitating deep relaxation by da

Of particular interest in children is the brain’s remarkable neuroplasticity. Pediatric hypnosis capitalizes on this developmental window, during which repeated hypnotic sessions-incorporating positive imagery, metaphors, and behavioral reframing-can strengthen beneficial neural circuits through long-term potentiation, the fundamental mechanism of learning and memory[16]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies suggest that hypnotically induced alterations in connectivity between sensorimotor, limbic, and executive control networks can persist beyond the hypnotic state, supporting long-lasting therapeutic change[9]. For developing brains, this represents a powerful opportunity: Hypnosis is not only a tool for symptom relief but also a method of reshaping maladaptive patterns and reinforcing adaptive ones[17].

Psychologically, two dominant frameworks inform our understanding of hypnosis. The neodissociation theory posits that hypnosis induces a division in consciousness, allowing suggestions to bypass usual cognitive filters while a “hidden observer” retains awareness[18]. In contrast, sociocognitive theories emphasize the influence of expectations, social context, and the therapeutic relationship, viewing hypnotic behavior as an enactment shaped by belief and motivation. These models are not mutually exclusive and likely work in tandem, especially in pediatric patients[19]. Children’s vivid imaginations, fluid cognitive structures, and natural responsiveness to social cues render them particularly susceptible to both dissociative and expectancy-driven mechanisms[20].

Developmental factors further amplify hypnotic responsiveness in children-especially those aged five to twelve-who consistently demonstrate higher suggestibility than adults. This is not due to gullibility, but reflects neurodevelopmental features such as an immature prefrontal cortex, greater reliance on imaginative cognition, and limited internal skepticism[4]. These attributes allow children to enter hypnotic states more easily and respond more deeply to metaphor, guided imagery, and sensory-based suggestions, making hypnosis particularly effective in pediatric settings[16].

Imagination, in fact, serves as the cornerstone of pediatric hypnotherapy. Techniques such as storytelling, guided imagery, and symbolic metaphors are developmentally tailored to engage a child’s sensory world and internal narrative. A child afraid of a medical procedure might imagine being in a superhero’s fortress or adjusting a pain “volume dial” in a brain-based control room[21]. These strategies are more than distractions-they actively engage brain regions involved in perception, regulation, and belief, creating a neurological basis for therapeutic transformation. Figure 3 summarizes the neuro-cognitive pathway of hypnosis, from influencing factors to clinical outcomes[8].

Finally, from an ethical and safety standpoint, clinical hypnosis in pediatric populations is considered safe when conducted by qualified professionals. It respects the child’s autonomy and emphasizes collaboration, never control. Informed consent from caregivers and assent from the child are essential[22]. As an adjunct-not a replacement-to standard care, hypnosis aligns with the principles of integrative medicine, offering a low-risk, high-benefit strategy that empowers children to manage symptoms, develop resilience, and participate actively in their own healing process[7]. It is important to note, however, that mechanistic insights-such as altered brain connectivity, neurotransmitter modulation, or engagement of neuroplastic processes-do not automatically translate into consistent clinical benefit. While these findings provide biological plausibility and support for the therapeutic potential of hypnosis, the strength of clinical outcomes in pediatric populations remains variable. It requires confirmation through well-designed, large-scale trials.

While the core principles of hypnosis-inducing a state of focused attention and heightened suggestibility-remain consistent across all ages, the practice of hypnotherapy with children is a specialized discipline that differs fundamentally from its adult counterpart[21]. These distinctions are not superficial; they are rooted in the unique developmental, cognitive, and relational landscape of childhood, demanding significant adaptations in technique, therapeutic alliance, and ethical considerations[23].

The most profound divergence lies in cognitive and developmental factors. Children, particularly in their primary school years, possess a natural and powerful capacity for vivid imagination, coupled with a less developed critical filter. This makes them exceptionally receptive to hypnotic suggestion when delivered through the language they understand best: Storytelling, metaphor, and play[24]. A pediatric therapist might guide a child to imagine a superhero's shield for protection from pain or a magic glove for needle-related procedures. In contrast, adult hypnotherapy must often navigate a more established analytical mindset, potential skepticism, and a lifetime of ingrained beliefs. Consequently, adult-focused techniques frequently rely on more direct suggestions, structured scripts, and insight-oriented approaches that appeal to a mature cognitive framework[4].

These differences directly influence the therapeutic relationship and session structure. Establishing rapport with a child is an active, often playful process that involves using toys, drawing, or engaging in informal conversation to build trust and comfort. With adults, this alliance is typically forged through empathetic conversation and a more formal discussion of goals and concerns[25]. This leads to pediatric sessions being shorter, more flexible, and dynamic, accommodating a child's variable attention span. Furthermore, pediatric hypnotherapy is uniquely characterized by the integral role of parents, creating a triadic therapeutic alliance among the therapist, child, and caregiver. Parents provide crucial background information, offer support during the process, and are essential for reinforcing hypnotic strategies at home-a dynamic entirely absent from adult therapy, where confidentiality and individual autonomy are paramount[26].

Ultimately, the goals and ethical boundaries of therapy are significantly influenced by the client's age. Pediatric hypnotherapy is often targeted and symptom-focused, aiming for relatively rapid relief from specific issues such as procedural anxiety, enuresis, chronic pain, or phobias[27]. While adult hypnotherapy can also be symptom-focused, it frequently delves deeper into complex psychological exploration, trauma resolution, and the unpacking of intricate cognitive-emotional patterns. This distinction informs the ethical framework: For adults, informed consent from the individual is sufficient[28]. For children, a dual process of obtaining informed consent from the legal guardian and, crucially, securing the age-appropriate assent (willing agreement) of the child is an ethical necessity, ensuring the intervention is collaborative, respectful, and empowering for the young client[29]. Table 2 summarizes the differences between pediatric vs. adult hypnotherapy.

| Feature | Pediatric hypnotherapy | Adult hypnotherapy |

| Cognitive & developmental approach | Leverages imagination and reduced critical filtering; techniques are concrete and story-based | Engages analytical reasoning and belief systems; techniques are more direct and insight-oriented |

| Therapeutic alliance & rapport | Built through playful interaction (e.g., games, drawing, storytelling) to foster trust | Built through empathetic conversation, active listening, and discussion of therapy goals |

| Imaginative engagement | Highly responsive to fantasy, symbols, and imaginative play | May be more analytical and less suggestible to symbolic or fantastical content |

| Communication style & techniques | Uses simple, multisensory imagery and playful metaphors (e.g., “magic glove”) | Uses abstract language, sophisticated metaphors, and direct cognitive-behavioral suggestions |

| Language style | Concrete, playful, and developmentally tailored | Abstract, metaphorical, and insight-driven |

| Session structure & pacing | Shorter, flexible, and dynamic to match attention span; includes playful transitions | Longer, more structured; allows sustained exploration of deeper issues |

| Session duration | Typically 20-40 minutes, adapted to the child’s mood and readiness | Typically 45-60 minutes with more consistent pacing |

| Therapeutic focus | Targets specific symptoms (e.g., pain, anxiety, enuresis); goal is rapid relief and empowerment | May address broader emotional patterns, trauma, and psychological insight |

| Support system involvement | Triadic alliance-parents contribute history, encourage participation, and reinforce strategies at home | Client works independently; support system involved only with consent (e.g., in family therapy) |

| Parental role | Actively involved during and between sessions | Not involved unless part of a joint therapeutic approach |

| Consent & ethical framework | Requires dual process: Informed consent from guardian + age-appropriate assent from the child | Solely requires informed consent from the adult client |

Pediatric clinical hypnotherapy is a specialized therapeutic approach that leverages children’s rich imagination, developmental stage, and innate responsiveness to create a safe, engaging, and effective healing experience. In contrast to adult hypnotherapy, which often employs more structured or directive methods, pediatric hypnotherapy is highly adaptable, playful, and centered on the child’s needs and preferences[21]. It emphasizes gentle guidance, collaboration, and the therapeutic power of imagination. There are four core principles essential for a successful clinical hypnotherapy session in children: Child-centered and developmentally tailored, indirect and permissive language, imaginative engagement and playfulness, and strength-based and resource-oriented[7]. Table 3 summarizes the different categories of clinical hypnotherapy techniques for children.

| Category | Technique | Description | Primary clinical application |

| Foundational imaginative techniques | Guided imagery/"safe place" | Guiding the child to create a multi-sensory, immersive experience of a safe, pleasant, or empowering environment (e.g., a beach, spaceship, magical forest) | Anxiety reduction, establishing rapport, creating a receptive state for further therapeutic work |

| Storytelling & therapeutic metaphor | Embedding therapeutic ideas within a narrative structure that reframes the child's problem and offers solutions indirectly (e.g., a story about a scared lion who finds its roar) | Problem-solving, reframing fears, enhancing coping skills in a non-threatening manner | |

| Pain & physical symptom control | Symptom-modifying imagery | Utilizing mental imagery to directly alter the perception of a symptom. Includes: (1) Glove anesthesia: Transferring imagined numbness; (2) Control panel/dials: Adjusting intensity; and (3) Transforming qualities: Changing the color/shape/temperature of pain | Direct modulation of pain, discomfort, or other physical sensations (e.g., itch, nausea) |

| Dissociative imagery | Guiding the child to imagine separating from the sensation, such as watching the pain on a screen, placing it in a box, or floating away from their body | Reducing the emotional component (suffering) of pain; managing overwhelming sensations | |

| Behavioral & habit reversal | Imaginative rehearsal & future pacing | Guiding the child to mentally rehearse successfully navigating a future challenging situation (e.g., a medical procedure, a school presentation) while feeling calm and confident | Building competence and positive expectancy; reducing anticipatory anxiety |

| Gentle aversion imagery | Associating an unwanted habit (e.g., nail-biting) with a mildly unpleasant but not frightening image or sensation (e.g., a bitter taste, a gritty texture) | Discouraging habits like thumb-sucking, nail-biting, or trichotillomania | |

| Ego-strengthening and empowerment | Ego-strengthening suggestions | Using direct suggestions and metaphors focused on building the child's sense of self-worth, resilience, and inner resources (e.g., "You have a special strength inside you") | Universal application to improve self-esteem, coping, and a sense of agency. Often integrated into all other techniques |

| Core linguistic techniques | Permissive & indirect language | Phrasing suggestions in an open, invitational manner ("You might begin to notice...", "Perhaps you can imagine...") that respects the child's autonomy | Bypassing resistance, fostering a sense of control and collaboration, empowering the child |

| Direct suggestion | Clear, positive, goal-oriented statements, often couched in permissive language ("And you can allow yourself to feel calm and relaxed") | Reinforcing desired changes, providing clear direction when the child is highly receptive |

Every session is customized to align with the child’s cognitive level, emotional maturity, interests, and specific challenges. Therapists often incorporate familiar characters, games, or themes the child enjoys, ensuring the experience feels relatable and safe. Rather than using commands, therapists employ permissive and open-ended language such as, “You might begin to notice…” or “Perhaps you can imagine…” This strategy encourages participation without pressure, enhancing the child’s sense of autonomy and reducing resistance[16,30]. Hypnotherapy taps into children's natural capacity for fantasy, pretend play, and storytelling. Therapeutic sessions are framed as creative adventures, making the process enjoyable and non-threatening while fostering emotional openness. The approach focuses on activating the child’s internal resources-such as resilience, creativity, and courage-to build confidence and develop effective coping mechanisms. Positive reinforcement is consistently embedded in the hypnotic work[21].

There are various techniques in pediatric hypnotherapy, including guided imagery and imaginative journeys, storytelling and metaphorical healing, permissive direct suggestions, ego-strengthening techniques, pain management strategies, creative aversion techniques, and future pacing. In guided imagery and imaginative Journeys, children are led through vivid, multi-sensory visualizations to calming or magical “safe spaces” (e.g., enchanted forests, superhero hideouts, underwater kingdoms). These mental environments serve as therapeutic platforms where healing narratives unfold-for example, imagining a “worry monster” shrinking and being locked away during a session on anxiety[31]. In storytelling and metaphorical healing, therapists craft or adapt therapeutic stories embedded with metaphors relevant to the child’s experience[32]. For example, a tale about a young explorer overcoming a storm may represent a child ma

Various pain management strategies, such as glove anesthesia, mental control panels, altering sensory qualities, dissociation techniques, creative aversion techniques, and future pacing, can be used to reduce organic and functional pain in children. In glove anesthesia, children imagine wearing a magical glove that numbs their hand. The numbness is then mentally transferred to a specific area experiencing pain, reducing discomfort[35]. In mental control panels, children are guided to visualize an internal control panel with sliders or dials that can be turned down to relieve pain, anxiety, or other distressing sensations. Therapists can also alter sensory qualities to help children change the sensory characteristics of their discomfort-such as imagining pain becoming smaller, cooler, or changing color-thereby reframing the pain perception[36].

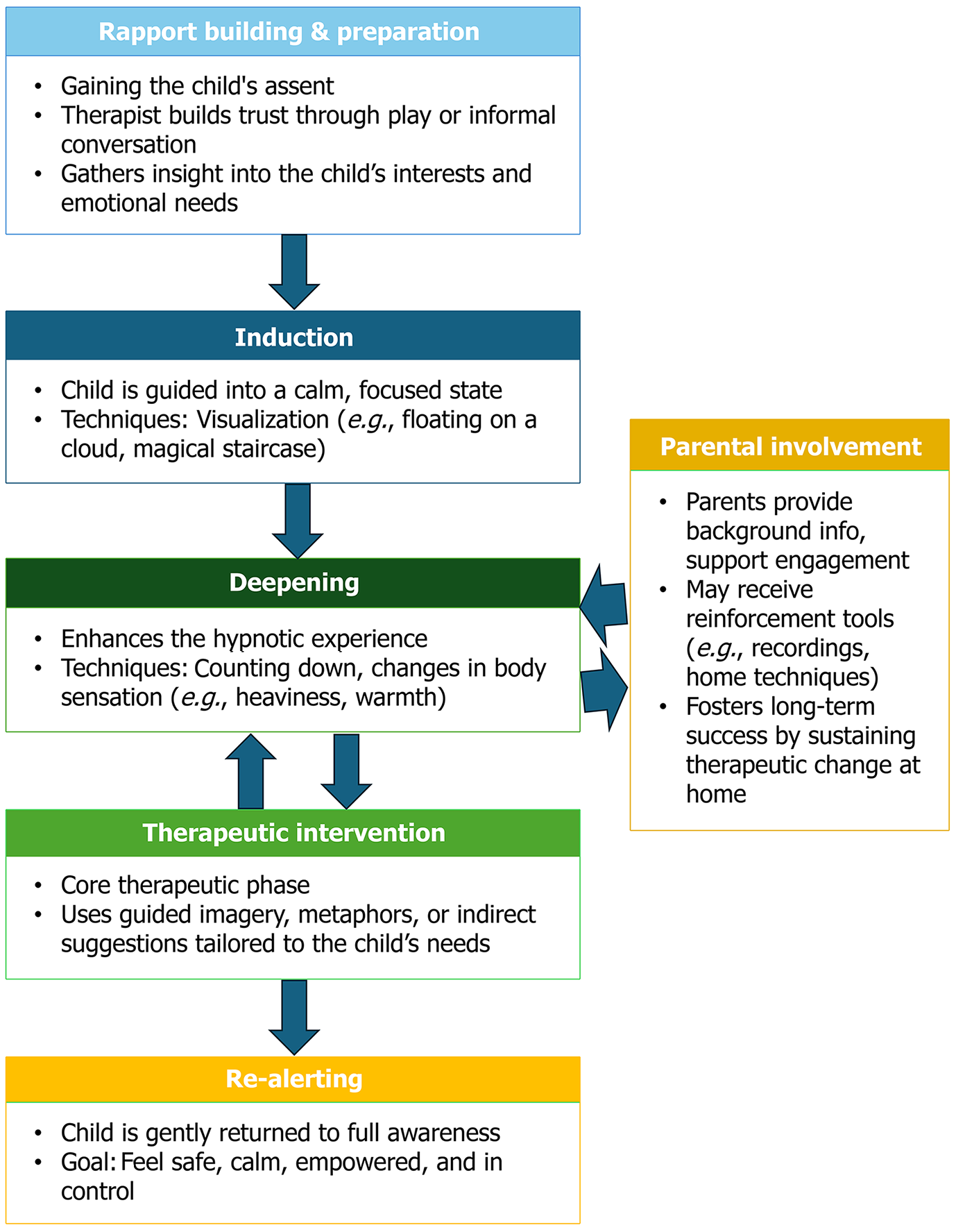

In dissociation techniques, children may be encouraged to imagine their pain floating away, being placed outside their body, or turning into something manageable and distant[37]. Creative aversion techniques can be used to manage habit disorders, such as thumb-sucking, where imaginative aversion can be gently introduced. For example, suggesting that the finger may taste unpleasant when placed in the mouth, while always maintaining a positive, supportive tone. In future pacing, children are encouraged to visualize themselves successfully using their new coping skills in upcoming real-life situations, reinforcing therapeutic gains and building confidence in their self-efficacy[38-40]. In all these techniques, the pediatric hypnotherapist should act as a warm, responsive guide-building rapport through playful interaction, active listening, and empathy. A soft, rhythmic voice and the ability to follow the child’s lead are essential. Flexibility is key, as the therapist must continuously adjust their approach based on the child’s cues and level of engagement to maintain the hypnotic focus[21]. A typical pediatric hypnotherapy session follows a structured, yet flexible format designed to meet the child’s developmental and emotional needs (Figure 4). It begins with rapport building and preparation, where the therapist engages the child through informal conversation or play to establish trust and gain insight into the child's interests and concerns[16]. This is followed by the induction phase, in which the child is guided into a focused, relaxed state using gentle and imaginative techniques such as visualizing themselves floating like a cloud or walking down a magical staircase[41]. The deepening stage follows, involving methods such as counting down or imagining shifts in bodily sensations-such as feeling heavier, lighter, warmer, or cooler-to enhance the depth of the hypnotic experience[1]. Once the child is comfortably immersed, the therapeutic intervention takes place, often involving guided imagery, metaphorical stories, or indirect suggestions carefully tailored to address the child’s specific challenge. The session concludes with re-alerting, where the child is gently and gradually returned to full awareness, typically feeling calm, safe, empowered, and in control[42].

Parents or caregivers play an essential supportive role. They provide background information, encourage the child’s engagement, and often learn simple reinforcement techniques or receive audio recordings for home practice. Repeated exposure to hypnotherapy reinforces new neural pathways and coping strategies, enhancing long-term outcomes and strengthening the child’s sense of control and well-being. Involving the family also fosters a supportive environment that sustains therapeutic change beyond the session[16].

Pediatric hypnotherapy has become a versatile and evidence-based therapeutic approach that assists children with a wide range of clinical conditions. By harnessing the child's imagination and suggestibility, hypnotherapy can be effectively used in various medical and psychological settings[7]. Its clinical applications include pain management-covering both acute procedural pain, such as needle phobia, and chronic pain conditions like headaches and fibromyalgia-as well as functional somatic disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and enuresis[43]. Additionally, it plays a valuable role in addressing behavioral and psychological issues such as anxiety, phobias, sleep problems, and habitual disorders. Hypnotherapy also functions as a supportive measure for symptom relief in chronic organic illnesses like cancer, cystic fibrosis (CF), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly in reducing pain, nausea, and anxiety[44]. It enhances patient comfort during diagnostic and surgical procedures, supports neurodevelopmental [e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)] and psychosomatic conditions [e.g., functional neurological disorders (FND)], and aids in addressing pediatric dermatological issues, including warts and eczema[42]. Through its flexibility and child-centered approach, hypnotherapy makes a significant contribution to comprehensive pediatric care. An expanding body of clinical research highlights the therapeutic benefits of hypnotherapy across a wide range of pediatric conditions[21]. Drawing upon key studies and well-established clinical observations, hypnotherapy has demonstrated both efficacy and safety in treating physical and psychological conditions in children and adolescents. This section synthesizes current evidence by condition, age group, and intervention method[45]. Tables 4 and 5 summarize the different clinical applications of hypnosis in pediatric medicine with the degree of recommendation.

| Medical domain | Specific applications & conditions | Degree of recommendation |

| Pain management | Acute procedural pain: Venipuncture, intravenous cannulation, lumbar puncture, bone marrow aspiration, burn dressing, dental procedures, post-operative pain, suturing, catheterization. Chronic/recurrent pain: Functional abdominal pain, migraines, tension headaches, fibromyalgia, sickle cell crises, juvenile arthritis, CRPS, neuropathic, and phantom pain | A |

| Anxiety & phobias | Procedural anxiety, preoperative fear, needle phobia (trypanophobia), dental phobia, “white coat” syndrome, generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, social and performance anxiety, panic attacks | A |

| Oncology | Pain from procedures and treatment, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (especially anticipatory), procedural anxiety, fatigue, emotional coping, and appetite improvement | A |

| Gastroenterology | IBS, functional abdominal pain, dyspepsia, cyclic vomiting syndrome, functional nausea, encopresis, constipation, rumination syndrome, IBD-related pain, and anxiety | B |

| Neurology/behavioral health | Tics, Tourette's, habit cough, PNES, FND, sleep disorders, nocturnal enuresis, anger and impulse control issues, and bruxism | B |

| Dermatology | Atopic dermatitis (itch-scratch cycle), warts, trichotillomania, excoriation disorder, psoriasis, and neurodermatitis | B |

| Pulmonology | Asthma-related anxiety, hyperventilation syndrome, procedural anxiety in cystic fibrosis, and treatment adherence (e.g., nebulizers/inhalers) | B |

| General health & wellness | Stress management, focus and concentration (non-ADHD specific), self-esteem, habit cessation (e.g., nail biting), body image, sleep hygiene, relaxation training, and reinforcement of a healthy lifestyle | B |

| Urology | Nocturnal enuresis, functional voiding disorders, urgency/frequency syndromes, and anxiety during urodynamic testing | B |

| Rehabilitation & physical therapy | Enhancing pain tolerance during therapy, improving motivation, managing movement fear, and recovering from injury | C |

| Endocrinology & metabolism | Support for insulin injections, blood glucose monitoring, and coping with chronic illness stress (e.g., diabetes) | C |

| Condition treated | Age group | Ref. | Method used | Outcome measures | Efficacy | Level of evidence |

| Pain (acute & chronic, including procedural pain) | 5+ years, often up to adolescence | Chester et al[47], Kendrick et al[49], Miller et al[51] | Guided imagery, relaxation, direct suggestion, self-hypnosis training | Pain intensity (self-report, behavioral observation), anxiety, distress, need for analgesia, hospital stay duration | Significant reduction in pain, anxiety, and distress; reduced need for medication; shorter hospital stays. Often superior to standard care/other psychological interventions | RCTs, meta-analyses, systematic reviews |

| Pediatric headache | Children & adolescents (mean approximately 13 years) with recurrent headaches | Kohen and Zajac[61] | Self-hypnosis training for self-regulation | Headache frequency, intensity, duration | Frequency reduced from 4.5/week to 1.4/week; intensity from 10.3 to 4.7; duration from 23.6 hours to 3 hours; P < 0.01 | Level III (retrospective cohort) |

| 9-18 years with primary headaches (migraine, tension-type) | Jong et al[62] | Randomized trial: Hypnotherapy vs transcendental meditation vs progressive muscle relaxation | ≥ 50% reduction in headache frequency; pain coping; anxiety/depression | All groups improved; approximately 47% achieved ≥ 50% reduction at 9 months; no significance difference between interventions | Level I (randomized controlled trial) | |

| Children & adolescents with unspecified chronic/episodic headaches | Gysin[63] | 5-session hypnosis/self-hypnosis vs behavioral therapy | Frequency, intensity, sense of control | Hypnosis showed superior improvements in symptom control and self-regulation | Level II (comparative trial) | |

| Mean age of 15 years of children with stress-associated headaches | Anbar and Zoughbi[64] | Hypnosis + relaxation & imagery; insight exploration | Frequency/intensity change; relation to stressor type | 96% improved overall; insight generation improved outcomes in patients with fixed stressors | Level III (retrospective chart review) | |

| Adolescents with chronic daily headache | Kohen[65] | Tailored self-hypnosis instruction | Frequency, intensity, duration | Notable symptom reduction in cases unresponsive to other therapies | Level IV (case reports) | |

| IBS & FAP | School-age children, adolescents (e.g., 5-18 years) | Rutten et al[68], Vlieger et al[70], Vlieger et al[72] | Gut-directed hypnotherapy, self-hypnosis training (individual or group sessions, sometimes home-based eHealth) | Abdominal pain severity/frequency, adequate pain relief, quality of life, daily functioning, school absence, somatization | Significant reduction in pain, improved quality of life; often superior to standard medical treatment, with long-term improvements sustained at follow-ups | RCTs, cohort studies, systematic reviews |

| Nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting) | 8-13 years | Edwards and van der Spuy[77] | 6 standardized hypnotherapy sessions over 6 weeks | Decrease in enuretic episodes over 6 months | Significantly effective compared to no-treatment controls; trance induction not essential | Controlled clinical trial |

| 7-12 years | Seabrook et al[76] | Hypnotherapy with nightly audiotapes vs alarm therapy (RCT) | Success (14 dry nights), failure, relapse, self-esteem measures | Alarm therapy more effective (55.3% vs 19.4% success); hypnotherapy had lower relapse (non-significant) | RCT | |

| Anxiety disorders (general anxiety, dental anxiety, phobias) | 5-17 years | Minosh et al[81] | Hypnotherapy by trained nurse practitioner, long-term follow-up | Parent/child subjective rating (1-5 scale) | 55% of anxiety cases rated good-to-excellent; no adverse effects reported | Prospective pilot study |

| 6-10 years | Erappa et al[82] | Hypnosis vs acupressure vs audiovisual distraction | PR, RR, AR | All methods effective, but hypnosis most significant in reducing PR, RR, and AR | Randomized controlled trial | |

| 5-7 years | Girón et al[83] | Hypnosis vs tell-show-do | FLACC scale, heart rate, skin conductance | Significantly lower anxiety and pain in hypnosis group across all measures | Randomized controlled trial | |

| 3-12 years | Rienhoff et al[84] | Hypnosis + low-dose midazolam (0.4 mg/kg) | Venham score (behavior) & Wong-Baker scale | Good compliance; effective for short-term use. Slight decline in behavior over repeated sessions | Retrospective longitudinal observational study | |

| Sleep disorders | 7-17 years with Insomnia (sleep onset delay, nocturnal awakenings) | Anbar and Slothower[86] | Retrospective chart review, self-hypnosis training | Sleep onset latency, frequency of awakenings, somatic complaints | 90% improved sleep-onset latency; 52% resolution & 38% improvement in nocturnal awakenings; 87% improvement in related somatic symptoms | Level III (retrospective study) |

| 8-12 years sleep problems post-trauma (grief/Loss-related) | Hawkins and Polemikos[87] | Qualitative group-based hypnotherapy, self-hypnosis | Caregiver interviews, Southampton sleep management schedule | All participants learned self-hypnosis; qualitative improvement in sleep initiation and sleep-related anxiety reported by children and caregivers | Level IV (qualitative study) | |

| 8-12 years with sleep terror disorder/disorders of arousal | Kohen et al[88] | Case series: Self-hypnosis training ± imipramine | Polysomnography, symptom frequency, long-term follow-up | All 4 children in case report became asymptomatic over 2-3 years; similar success in 7 more patients treated with hypnosis alone | Level IV (case series) | |

| Habit disorders (e.g., habit cough, tic disorders, trichotillomania) | 8-year-old child with habit cough (case study) | Anbar[96] | Self-hypnosis; flexible rapport-building approach | Resolution of persistent cough | Rapid and complete symptom resolution in 1 session | Level IV (case report) |

| 6-17 years (n = 33) with Tics (Tourette syndrome) | Lazarus and Klein[94] | Self-hypnosis + videotaped training | Tic control via subjective report over 6 weeks | 79% showed improvement; 96% responded within 3 visits | Level IV (retrospective case series) | |

| 8-12 years (n = 4) with Tourette syndrome | Kohen and Botts[95] | Self-hypnosis (relaxation + imagery) | Tic frequency, medication reduction | Immediate and sustained improvement; reduced/ceased medication | Level IV (case series) | |

| 6-15 years (n = 5) with trichotillomania | Kohen[98] | Self-monitoring, dissociative techniques, self-hypnosis | Symptom resolution and behavior control | All children achieved control with individualized techniques | Level IV (case series) | |

| 7 years (case study) with thumb sucking | Grayson[97] | Hypnotic imagery, role-modeling, validation in trance | Cessation of habit | Successful resolution in one session | Level IV (case report) | |

| ASD | 5-10.99 years with GI symptoms, anxiety, and behavior in ASD with DGBI | Mitchell et[102] | Synbiotics alone vs synbiotics + GDHT, 12-week RCT | GI scores, anxiety levels, irritability behaviors, microbiota composition | GDHT group showed significant reductions in GI pain, anxiety, and irritability; synbiotics helped both groups | Level II (randomized controlled trial) |

| 6-year-old child with atypical autism & severe ego deficits | Gardner and Tarnow[103] | Adjunctive hypnotherapy with music integration | Specific behavior change, social/cognitive skill improvement | Behavioral goals achieved; sustained gains at 18-month follow-up | Level IV (case report) | |

| 6-12 years (approximately) who need dental cooperation and hyperactivity in ASD | Sartika et al[104] | Hypnotherapy before dental scaling (quasi-experimental) | Cooperative attitude, calculus index | Significant improvement in cooperation and reduction in calculus (P = 0.000) | Level III (Quasi-experimental design) | |

| 14-15 years with engagement, anxiety, attention in ASD | Austin et al[105] | Virtual reality hypnosis (4 sessions, feasibility study) | Engagement, parental reports on behavior and anxiety | No change in autistic symptoms, but improved engagement and relaxation; parental satisfaction noted | Level V (feasibility/pilot study) | |

| ADHD | Children (mean age approximately 10) with ADHD | Calhoun and Bolton[100] | Hypnotherapy by psychologists/physicians; attempts to hypnotize 11 children, 1 completed full session | Pre- and post-hypnosis behavioral observations | Significant improvement in behavior in the successfully hypnotized child | Low (small sample, non-randomized) |

| Children (median age 122) with low self-esteem in ADHD, epilepsy, anxiety | Hazard et al[112] | Standardized hypnosis protocol, single therapist, prospective single-center study | Self-esteem measured via Jodoin 40 scale, Piers-Harris self-concept scale, and self-rated score | Statistically significant improvement in self-esteem (P ≤ 0.05), no side effects | Moderate (pilot exploratory study) | |

| 11-year-old child with ADHD & written language disorder | Hery-Niaussat et al[113] | SCED, 4 hypnosis sessions over 8 weeks | Reading tests, phonological processing, attention, self-esteem | Statistically significant improvement in text reading (P = 0.028), attention (P = 0.031), and self-esteem (P = 0.002) | Moderate (SCED, but detailed measures) | |

| Oncology support | Children (3 cases, female) with cancer-related anxiety | Talebiazar et al[121] | Classical hypnotherapy, 8 sessions with 1-month follow-up | HADS at 5 time points | Significant reduction in hospital anxiety during and after intervention | Level 4 (case report) |

| Children (11-17 years) with Cancer-related distress & QoL | Grégoire et al[120] | Hypnosis-based group intervention with monthly 2-hour sessions | Self-reported emotional well-being, relaxation, assertiveness, and parent-child communication | High acceptability; perceived improvement in quality of life, emotional regulation, and family coping | Level 3 (pilot/quasi-experimental) | |

| Children and adolescents (0-25 years) with cancer and had Procedural anxiety & pain in | Nunns et al[118] | Meta-analysis of RCTs, 8 hypnosis studies included | Procedural anxiety, fear, distress, and pain | Large, statistically significant reductions in procedural anxiety (d = 2.30) and pain (d = 2.16) | Level 1a (meta-analysis of RCTs) | |

| CINV | Richardson et al[119] | Meta-analysis of 6 RCTs (5 in pediatric population) | Frequency/severity of anticipatory and acute CINV | Statistically significant reduction in anticipatory and acute CINV; effect comparable to CBT | Level 1a (meta-analysis of RCTs) | |

| Asthma | Children with chronic asthma | Alexander et al[128] | Relaxation training (5 sessions after control phase) | Pulmonary function, muscle tension, heart & respiratory rates, skin conductance | No significant improvement in pulmonary function; relaxed state achieved | Level III (quasi-experimental, physiological measures) |

| Pediatric to adolescent age (exact age not specified) | Morrison[127] | Hypnotherapy over 1 year | Hospital admissions, medication use, airflow, patient-reported improvement | Reduced admissions, reduced drug use, improved perceived symptoms; variable objective airflow | Level II (controlled clinical trial, small sample) | |

| Pediatric (age varied across 251 RCTs) | Moher et al[129] | Systematic review of CAM RCT reporting (including hypnosis and relaxation interventions) | CONSORT adherence, Jadad score, allocation bias, adverse event reporting | Revealed poor methodological quality and underreporting in pediatric CAM RCTs | Level I (systematic review of RCTs -methodology focus) | |

| 8-18 years with chronic dyspnea (non-organic) | Anbar[125] | Self-hypnosis instruction (1-2 sessions) with follow-up | Dyspnea frequency/severity, associated symptoms, self-reported resolution, treatment withdrawal | 13/16 resolved within 1 month; 11/16 attributed improvement to hypnosis; no recurrence during follow-up | Level IV, retrospective chart review; small number, good follow-up | |

| Cystic fibrosis | 7-18 years | Belsky and Khanna[134] | Self-hypnosis (pilot RCT with matched control) | Locus of control, trait anxiety, self-concept, peak expiratory flow rate | Significant psychological and physiological improvements in the experimental group vs control | Level II (small RCT with limitations) |

| 7-49 years (mean 18.1) | Anbar[122] | Self-hypnosis taught in 1-2 sessions, patient-reported outcomes | Symptom control (pain, headache, taste of medication), self-reported efficacy | 86% success rate; no adverse effects; high subjective benefit | Level IV (case series with self-report and no control) | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | 12-65 years with IBS-type symptoms in IBD | Hoekman et al[137] | Gut-directed hypnotherapy (RCT) | ≥ 50% reduction in IBS-SSS score at 6 months | No superiority over standard medical treatment | Level I (RCT) |

| Adolescents (mean age 158) with Crohn’s disease | Lee et al[138] | 1 session CH + self-hypnosis (RCT pilot) | QoL, abdominal pain, school absences | Improved parent-reported QoL & pain reduction | Level II (pilot RCT) | |

| 10-17 years with IBD | Shaoul et al[139] | 4-12 sessions tailored hypnosis | Symptom resolution, reduced inflammatory markers | Symptom resolution in most cases; well-tolerated | Level IV (case series) | |

| Adults with UC-active | Mawdsley et al[140] | 1 session gut-focused hypnosis | IL-6, SP, IL-13, rectal blood flow | Significant reduction in inflammatory markers | Level II (controlled physiological study) | |

| Adults with UC- quiescent | Keefer et al[141] | 7 sessions of gut-directed hypnotherapy vs control | Relapse rate over 1 year | 68% maintained remission vs 40% in control | Level I (RCT) | |

| Atopic dermatitis | Adults & children | Stewart and Thomas[164] | Hypnotherapy; individualized sessions | Subjective (patient reports), objective clinical assessments, long-term follow-up | Significant immediate and sustained improvement in itching, sleep disturbance, and mood (P < 0.01); maintained up to 2 years | Level II (Quasi-experimental study with control, non-randomized) |

| Adults (mean age: 34.5 years) | Delaitre et al[165] | Hypnosis (mean of 6 sessions, range 2-16) | EASI score before and after intervention | Improvement/resolution in 26 of 27 patients; mean EASI score reduced from 12 to 2.8 | Level III (prospective clinical cohort without control group) | |

| Children (> 5 years) | Derrick et al[166] | Self-hypnosis using guided imagery | Clinical assessment of eczema symptoms over 18 weeks | Mild-to-moderate benefit observed; did not reach statistical significance | Level IV (Pilot study; no control group, low statistical power) | |

| Viral warts | Adult women with HPV-related genital warts | Barabasz et al[156] | Hypnosis vs standard medical therapy | Number and size of lesions; complete clearance at 12 weeks | Statistically significant reduction in lesions with hypnosis (P < 0.04); complete clearance 5 × more likely in hypnosis group than medical therapy | Level II (randomized controlled clinical trial) |

| Adults with common warts (cutaneous) | Spanos et al[154] | Hypnotic suggestion vs placebo vs no treatment | Wart regression rates; vividness of imagery | Hypnosis and suggestion led to greater wart regression than placebo or no treatment; imagery vividness predicted better outcomes | Level II (experimental controlled design) | |

| Adults with common warts (cutaneous) | Spanos et al[155] | Hypnosis, salicylic acid, placebo, no treatment | Wart count at 6-week follow-up | Only hypnosis group had significantly more wart regression vs control; equal treatment expectation across all groups | Level I (randomized controlled trial) |

Pain management (acute and chronic): Hypnotherapy has emerged as a promising, valuable, and increasingly re

In the realm of acute pain management, hypnotherapy is frequently and effectively employed in medical settings involving painful or anxiety-provoking procedures. These commonly include venipuncture, intravenous cannulation, lumbar punctures, bone marrow aspirations, wound care, burn dressing changes, dental procedures, and even minor surgical interventions[47]. Hypnotic techniques utilized in these situations primarily focus on potent strategies such as distraction, dissociation (creating a sense of detachment from the physical sensation), and the construction of elaborate, protective mental imagery designed to shift the child's attention dramatically away from the noxious stimulus[48]. For instance, a child might be guided to imagine vividly being transported to a safe and utterly calming place-such as floating weightlessly in outer space, swimming gracefully underwater with friendly dolphins, holding an impenetrable magical shield that completely blocks discomfort, or even transforming into a powerful superhero impervious to pain. These imaginative techniques are highly effective in reducing pre-procedural anxiety, significantly lowering reported pain ratings, and often leading to a decreased reliance on pharmacological analgesics or sedatives. Robust clinical studies have consistently demonstrated that children undergoing hypnotherapy during procedures report substantially less distress, exhibit reduced physiological signs of pain (e.g., lower heart rate, stable blood pressure, decreased cortisol levels), and often experience faster recovery times post-intervention, highlighting its physiological as well as psychological benefits[49].

Within the context of chronic pain, a pervasive and debilitating issue in pediatric populations (e.g., recurrent ab

Crucially, the benefits of hypnotherapy go beyond reducing symptoms to improve important functional outcomes, such as regular school attendance, better sleep quality, increased participation in physical activities, and an overall boost in quality of life[53]. A key element of long-term success is teaching children self-hypnosis techniques, allowing them to practice these skills outside of therapy sessions on their own, which promotes independence, lasting symptom relief, and lifelong coping strategies[54]. Clinical hypnotherapy, utilizing techniques like guided imagery, relaxation, and self-hypnosis training, has consistently demonstrated significant reductions in pain intensity, anxiety, and distress in pediatric patients, often outperforming standard care[55]. This robust efficacy is substantiated by the highest tier of evidence, including RCTs, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews. Notably, research by Kohen et al[56] and Olness[57] revealed that children as young as three years old can effectively apply self-hypnosis techniques, with proficiency generally increasing with age. Their findings also indicated an inverse correlation between clinical success and the number of visits, sug

In both acute and chronic pain settings, the successful implementation of hypnotherapy is critically dependent on its delivery by trained and experienced clinicians who can expertly tailor scripts and techniques to the unique developmental level, cognitive capacity, and individual interests of each child[58]. Sessions typically involve a thoughtfully structured combination of initial rapport-building, gentle induction into the hypnotic state, careful deepening techniques, the delivery of individualized therapeutic suggestions, and "future pacing" to reinforce successful application of new skills in real-life scenarios[59]. Active involvement of caregivers is paramount, as they play a vital role in reinforcing techniques and supporting the child's practice at home, thereby ensuring the sustained integration of hypnotherapeutic benefits into daily life, which is a key component of a comprehensive, integrative pediatric pain management plan[21].

Pediatric headache: Headache is among the most common and disabling pain complaints in children and adolescents, with migraine and tension-type headaches accounting for the majority of cases. These headaches often arise from a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, stress, emotional dysregulation, sleep disturbances, and environmental triggers[60]. While pharmacological treatments remain foundational, increasing attention is being given to mind-body approaches-particularly clinical hypnotherapy-as both adjunct and primary modalities for pediatric headache mana

Hypnotherapy offers a non-invasive, safe, and empowering intervention that helps children regulate pain perception, reduce headache frequency and severity, and gain control over associated physiological and emotional responses[61]. Typically, children are guided into a focused, deeply relaxed state and taught self-hypnosis techniques such as vis

The evidence base for hypnotherapy in pediatric headache is robust and continually expanding. A retrospective study by Kohen and Zajac[61] involving 144 children and adolescents taught self-hypnosis reported significant reductions in headache frequency (4.5-1.4 per week), intensity (10.3-4.7), and duration (23.6-3.0 hours), with no adverse effects. Similarly, a randomized clinical trial by Jong et al[62] compared hypnotherapy, transcendental meditation, and pro

Other research supports hypnotherapy’s superiority in certain domains. In a comparative trial, Gysin[63] found hypnosis/self-hypnosis to be more effective than behavioral therapy or medical counseling alone in reducing headache intensity and improving the sense of self-efficacy in children with chronic or episodic headaches. In a more psychosocially oriented study, Anbar and Zoughbi[64] observed that 96% of children reported improvement with hypnosis, and highlighted the importance of insight generation, especially among children whose headaches were linked to fixed stressors. Finally, Kohen[65] presented compelling case reports of adolescents with chronic daily headaches who found dramatic relief from self-hypnosis after failing to respond to both medication and other therapies-underscoring the potential of hypnotherapy even in treatment-resistant cases.

A key distinguishing feature of hypnotherapy is its integration of deep relaxation, cognitive reframing, and ima

Pediatric functional somatic syndromes: Functional somatic syndromes in children, encompassing conditions like IBS, functional abdominal pain (FAP), and enuresis, are characterized by real and distressing symptoms despite the absence of identifiable organic pathology[67]. These pervasive conditions often lead to significant disruptions in a child's daily life, affecting school attendance, social engagement, and overall psychological well-being. Thankfully, hypnotherapy has emerged as a compelling, evidence-supported therapeutic option for these disorders. Its effectiveness lies in its unique ability to influence autonomic, GI, and urinary function through powerful psychophysiological mechanisms and ima

IBS and FAP stand as some of the most extensively studied pediatric conditions where hypnotherapy has demon

In an attempt to investigate factors that could affect the efficacy of hypnosis to relieve FAP, a 2023 exploratory study by de Bruijn et al[73] investigated whether specific genetic polymorphisms (COMT, OPRM1, and MAO-A), previously linked to adult hypnotizability, predict HT response in 144 children aged 8-18 with FAP disorders. The study found no sig

Clinical trials and strong long-term studies have consistently shown that pediatric gut-focused hypnotherapy results in significant and meaningful decreases in symptom severity, the frequency of painful episodes, and related functional disability[74]. Moreover, its effects are often notably long-lasting, with improvements persisting for months or even years after treatment ends. In addition to reducing symptoms, hypnotherapy can also positively affect GI motility, reduce visceral hypersensitivity (the increased perception of normal gut sensations), and help normalize autonomic nervous system responses, offering a truly comprehensive biopsychosocial approach. Its non-invasive, medication-free nature makes it especially attractive to families who are cautious about drug treatments or whose children do not respond to standard therapies[73].

Enuresis, particularly nocturnal enuresis (bedwetting), affects a substantial portion of school-aged children and can carry a significant emotional and social burden. While spontaneous remission is common with age, persistent cases often lead to profound embarrassment, reduced self-esteem, and disrupted sleep patterns for both the child and family[75]. Hypnotherapy provides a highly child-friendly and empowering intervention that actively encourages desired behavioral change. It works through subconscious conditioning, vivid imagery rehearsal, and powerful ego-strengthening su

During hypnotherapy sessions, children may be guided to imagine internal "bladder alarms" that signal them to wake up or "control panels" in their minds that help them manage nighttime urination. Alternatively, they might engage with stories where a character successfully learns to control bedwetting[76]. Therapists consistently incorporate confidence-building suggestions to reduce feelings of shame and foster a strong sense of mastery and achievement. Importantly, hypnotherapy respects the child's individual pace and provides a completely non-threatening, non-punitive environ

Research strongly supports the efficacy of hypnotherapy for treating nocturnal enuresis, particularly in pediatric populations. Multiple controlled studies, including randomized clinical trials, have demonstrated its therapeutic value. For instance, Edwards and van der Spuy[77] reported significant reductions in wet nights in boys aged 8-13 years fo

Pediatric hypnotherapy is a versatile and highly effective tool for addressing a broad spectrum of behavioral and psychological disorders in children and adolescents. These conditions frequently stem from, or are significantly exacerbated by, emotional dysregulation, chronic stress, trauma, or various developmental challenges[79]. Hypnosis offers a non-invasive, child-centered therapeutic modality that powerfully leverages imagination, heightened suggestibility, and inherent self-regulation capacities to address underlying psychological processes and promote adaptive behaviors[80]. Among the most common and well-supported indications for hypnotherapy in pediatric behavioral health are anxiety disorders and phobias, sleep disturbances, and habit disorders.

Anxiety disorders and phobias: Hypnotherapy is particularly effective in managing anxiety-related conditions in children, including generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, social phobia, test anxiety, insomnia, and specific phobias such as trypanophobia (needle phobia) or dental anxiety[79]. A growing body of research supports its efficacy across both psychological and procedural anxiety contexts. For instance, Minosh et al[81] conducted a prospective study involving 53 children treated for anxiety, nocturnal enuresis, or insomnia. They found that 55% of those with anxiety disorders and 59% with enuresis achieved good-to-excellent long-term outcomes. No adverse effects were reported, highlighting the safety and moderate effectiveness of hypnotherapy in pediatric populations.

In dental settings, RCTs have demonstrated even more compelling evidence for hypnosis as a tool for anxiety and pain reduction. Erappa et al[82] compared hypnosis with acupressure, audiovisual aids, and no intervention in 200 children aged 6-10 receiving local anesthesia. Hypnosis led to the most significant reductions in anxiety indicators, including pulse rate, respiratory rate, and observed anxiety behavior, outperforming all other interventions. Similarly, Girón et al[83] found that hypnosis was significantly more effective than the standard tell-show-do behavioral technique in lowering anxiety and pain during pulpotomy procedures, as measured by the FLACC scale, heart rate, and skin conductance throughout all treatment phases.

Children often experience anxiety as a vague, overwhelming sensation that is difficult for them to articulate, un

In cases of procedural or phobia-related anxiety, systematic desensitization can be embedded within the hypnotic trance. For example, a child with needle phobia might imagine themselves as a superhero who grows stronger and braver with each imagined encounter with a needle, eventually translating this confidence into real-life calm. A large-scale observational study by Rienhoff et al[84] involving over 300 children aged 3-12 treated with both midazolam and hy

Sleep disturbances: Sleep disturbances-including insomnia, bedtime resistance, night awakenings, nightmares, and sleep terrors-are common among children, especially during periods of stress, grief, or developmental transition. These issues often overlap with anxiety, somatic complaints, and emotional dysregulation[85]. Hypnotherapy offers a safe, non-pharmacological intervention that targets both the psychological roots and behavioral manifestations of pediatric sleep disorders. Through personalized imagery, ego-strengthening techniques, and relaxation training, children are empo

Neurodevelopmental disorders commonly present with sleep disturbances. In a pivotal retrospective chart review by Anbar and Slothower[86], 84 school-aged children (ages 7-17) with insomnia were treated using self-hypnosis techniques. Remarkably, 90% of those with prolonged sleep-onset latency experienced a significant reduction in the time it took to fall asleep. Additionally, 52% of children with frequent nocturnal awakenings reported complete resolution, while another 38% reported notable improvement. The study also found that 87% of children with related somatic complaints (e.g., chest pain, abdominal pain, habit cough) showed marked improvement following hypnotic intervention, highlighting hyp

Hypnotic strategies for sleep commonly include calming bedtime scripts, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery tailored to the child’s interests and developmental level. For example, children might be led to imagine floating gently on a cloud, drifting along a peaceful river, or being protected by a magical animal companion. These scripts not only lower physiological arousal but also create positive, soothing mental associations with sleep, replacing anxiety-driven narratives with safe and empowering ones[89,90]. Evidence from clinical studies and expert practice indicates that hypnotherapy reduces sleep latency, improves sleep continuity, and decreases nighttime fear and arousals, particularly when combined with psychoeducation and cognitive reframing. As sleep quality improves, children often experience a range of cascading benefits, including better mood regulation, enhanced attention and learning, and improved inter

Tic, functional neurological, and habit disorders: Tic disorders-including Tourette syndrome, FND, and other habit disorders such as nail biting, thumb sucking, trichotillomania, and habit cough- present complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in pediatric populations. These conditions often stem from underlying psychological factors such as anxiety, boredom, trauma, stress, or the need for self-regulation and self-soothing[91,92]. Although these behaviors may initially serve adaptive or protective functions, they often become entrenched through repetitive reinforcement, ultimately resulting in physical harm, social embarrassment, and diminished self-esteem.

Hypnotherapy has emerged as a safe, developmentally sensitive, and highly effective intervention for these disorders in children. Rather than relying on aversive or punitive strategies, hypnosis emphasizes positive suggestion, vivid imagination, self-regulation, and empowerment[7,93]. Its versatility allows for both diagnostic and therapeutic benefits, particularly in cases where conventional biomedical approaches have yielded limited success.

Tic disorders and Tourette syndrome: In tic disorders, hypnotherapy has been shown to help children become more attuned to premonitory urges-the sensations that precede tics-and develop voluntary control over tic expression through metaphoric, dissociative, and imagery-based techniques. Children may be guided to imagine a “switch” they can mentally activate to reduce tic frequency or redirect the urge into a less noticeable or calming behavior. This approach complements traditional behavioral therapies such as habit reversal training and is often perceived by children as more playful and engaging[94,95]. In a case series of 33 children with Tourette syndrome, self-hypnosis training supplemented with instructional video modeling led to symptom improvement in 79% of participants-96% of whom responded within three sessions[94]. Similarly, Kohen and Botts[95] documented a sustained reduction in tic frequency and a decreased reliance on medication through the use of relaxation and imagery techniques. These findings support hypnosis as an effective and child-friendly adjunctive therapy.

FND: FND encompasses a spectrum of psychogenic conditions, including functional movement disorders, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, and functional gait abnormalities. Hypnotherapy plays a dual role here: Diagnostically, it can produce temporary symptom resolution during trance, which helps confirm the psychogenic origin of symptoms. Therapeutically, hypnosis supports emotional reprocessing, reduces somatic hypervigilance, and facilitates motor re

Habit disorders and body-focused repetitive behaviors: Habit disorders such as thumb sucking, nail biting, trichotillomania, and habit cough can significantly interfere with social functioning and physical well-being. These behaviors are often maintained by unconscious reinforcement mechanisms and may be exacerbated by stress or trauma[91]. Hy

For example, Anbar[96] reported the rapid resolution of a habit cough in a child using a rapport-based, functional understanding of symptoms paired with hypnosis. Grayson[97] similarly documented the elimination of thumb-sucking in a 7-year-old girl after a single hypnosis session involving imaginative modeling and affirmation. Kohen[98] treated pediatric trichotillomania through a combination of self-monitoring, dissociative strategies, and customized imagery, successfully helping children gain control without inducing guilt or shame. These interventions consistently emphasize internal mastery and self-efficacy.

Across tic, FND, and habit disorders, hypnotic strategies include empowering imagery (e.g., visualizing protective paint on fingernails), ego-strengthening affirmations, and developmentally tailored metaphors. Children may visualize their fingers resisting the urge to bite or imagine hair becoming stronger each time they resist pulling. In tic and habit disorders, suggestions may also incorporate gentle, symbolic aversion (e.g., fingers tasting “sour” only when placed in the mouth) delivered within a nurturing and affirming therapeutic frame. Parental involvement is crucial in reinforcing treatment gains. Caregivers are coached to provide consistent, nonjudgmental support, celebrate small successes, and encourage practice of hypnotic techniques at home[4,79]. While further large-scale RCTs are warranted, the current body of clinical evidence and expert consensus support the integration of hypnotherapy into treatment plans for pediatric tic disorders, FND, and habit disorders. It offers rapid symptom relief, enhances self-awareness and emotional regulation, and promotes lasting behavioral change-all within a framework that empowers the child and fosters hope and enga

Pediatric hypnotherapy is increasingly recognized as a valuable adjunctive approach in the comprehensive management of certain neurodevelopmental and psychosomatic conditions[99]. This is particularly true when traditional therapies alone may not fully address comorbid symptoms such as anxiety, sleep disturbances, or associated functional im

While hypnotherapy is not a primary treatment for the core neurodevelopmental characteristics of ASD, mounting evidence supports its role as a highly valuable adjunctive intervention, particularly for managing the frequently co-occurring challenges seen in autistic individuals. These challenges include heightened anxiety, emotional dysregulation, sensory sensitivities, behavioral rigidity, low self-esteem, and significant difficulties with cooperation in unfamiliar or demanding settings such as clinical or dental procedures[101].

Several studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of hypnosis when tailored to the unique needs of autistic children. For example, Mitchell et al[102] conducted a RCT assessing GDHT in autistic children with disorders of gut-brain interaction. While synbiotics alone improved GI symptoms, the combination of synbiotics and GDHT significantly reduced anxiety and irritability, with sustained improvement in GI pain, indicating GDHT’s value in addressing both physiological and behavioral symptoms through a biopsychosocial lens. Similarly, Gardner and Tarnow[103] reported successful use of adjunctive hypnotherapy in a child with atypical autism and severe ego deficits. By incorporating music-a preferred interest and strength of the child-into hypnotherapy, the intervention led to improvements not only in targeted behaviors but also in broader social and cognitive skills, with effects maintained at 18-month follow-up. This highlights the importance of personalization and strength-based approaches in hypnosis with autistic populations.

Sartika et al[104] found that hypnotherapy prior to dental scaling in autistic children significantly improved cooperation and reduced oral health complications such as calculus accumulation. This evidence suggests that hypnosis can modulate behavioral responses to stressful stimuli, enhance compliance, and make necessary medical or dental procedures less traumatic. Additionally, Austin et al[105] explored the feasibility of virtual reality (VR)-based hypnosis in adolescents with ASD. While core autistic symptoms remained unchanged, participants were attentive and engaged, with parents reporting increased relaxation and willingness to participate-suggesting that hypnotic engagement, through novel modalities like VR, may help bridge therapeutic gaps by increasing accessibility and comfort.

Taken together, these studies underscore the versatility of hypnotherapy in addressing diverse ASD-related concerns-from anxiety and GI distress to cooperation and emotional self-regulation. Hypnotherapeutic techniques such as guided imagery, safe space visualization, metaphor-based coping scripts, and ego-strengthening affirmations can be adapted to support autistic children in emotionally overwhelming or inflexible states. Moreover, when sleep disturbances are present-a common issue in ASD-hypnosis can promote relaxation and improve sleep onset through calming bedtime scripts and anxiety modulation[106]. Crucially, the success of hypnotherapy in ASD depends on a neurodiversity-affirming, highly individualized approach. Interventions must be designed with sensitivity to the child’s communication preferences, sensory processing profile, and interests. Leveraging special interests (e.g., music, animals, or fantasy themes) and using concrete, literal language can significantly enhance receptivity and therapeutic engagement[107]. When integrated into a multidisciplinary care framework and administered by clinicians trained in both hypnotherapy and autism care, hypnotherapy can substantially improve quality of life and psychological resilience in autistic children-empowering them with tools for better self-regulation, reduced anxiety, enhanced cooperation, and a stronger, more positive sense of self.

Children with ADHD often face a constellation of challenges beyond core symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. These include heightened anxiety, sleep disturbances, low self-esteem, and specific learning difficulties-each of which can significantly affect quality of life, academic performance, emotional resilience, and social adaptation[108]. While traditional ADHD management often relies on pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions, hypno

Hypnotherapy does not aim to alter the neurocognitive underpinnings of ADHD directly, but it targets high-impact associated issues like anxiety, sleep dysregulation, and emotional dysregulation. For instance, hypnotic techniques-such as guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, breathing-focused induction, and metaphorical storytelling-help children learn to self-soothe, reduce physiological arousal, and transition more smoothly into sleep[110]. Children are often guided to imagine calming scenarios, such as gently floating on a cloud, slowing down a buzzing engine, or en

Emerging research strongly supports this approach. In a pioneering early study by Calhoun and Bolton[100], hyp

In clinical settings, practitioners often incorporate interactive metaphors tailored to children's developmental stages-such as superheroes mastering their impulses, magical calming objects, or adventure journeys into a “quiet mind cave”-to maximize engagement and therapeutic responsiveness. Additionally, children who learn self-hypnosis techniques report greater confidence, improved sleep initiation, fewer nocturnal awakenings, and reduced anxiety. These changes not only improve day-to-day functioning but also create a more receptive psychological state for other interventions, including medication titration or behavioral therapy[7]. Currently, clinical hypnotherapy is increasingly viewed not as a fringe or supplementary technique but as a credible and evidence-informed intervention for children with ADHD-especially those presenting with anxiety, sleep difficulties, learning disorders, or low self-esteem. When delivered by trained clinicians, hypnosis offers a non-invasive, empowering, and child-friendly strategy to support holistic development and psychological well-being in this vulnerable population. However, despite promising preliminary findings, the limited scope of current research makes it premature to draw firm conclusions about hypnosis as a reliable treatment for these conditions.

While often associated with behavioral or functional disorders, hypnotherapy has increasingly demonstrated significant value as an adjunctive intervention in managing symptoms linked to chronic and organic pediatric illnesses. Children confronting diagnoses such as cancer, CF, and IBD not only endure profound physical symptoms but also experience substantial psychological stressors. These stressors can exacerbate their primary condition, diminish treatment adherence, and severely impact their quality of life. Pediatric hypnotherapy, through its remarkable capacity to modulate perception, reduce distress, and enhance coping mechanisms, offers a safe, non-pharmacological strategy to improve overall well-being, alleviate symptom burden, and foster robust psychological resilience in these medically complex young po

Oncology support: Children undergoing cancer treatment frequently endure a multifaceted spectrum of distressing symptoms-including severe procedural pain, anticipatory anxiety, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, fatigue, and psychological distress related to repeated hospitalizations and invasive interventions. Hypnotherapy has emerged as a highly promising, non-pharmacological intervention to alleviate these burdens, empowering young patients with concrete psychological tools to manage both acute physical discomfort and profound emotional stress[115,116].