Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.109134

Revised: June 9, 2025

Accepted: October 15, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 233 Days and 18.6 Hours

Clinical decision-making in urinary tract infections depends heavily on accurately distinguishing between pathogenic and non-pathogenic organisms. The interpretation of urine culture results is influenced by proper sample collection, the patient's clinical context, and organism-specific characteristics. However, there is currently no definitive method to determine whether a urinary isolate is truly pathogenic. This distinction is critical, as treatment decisions hinge on it. This pioneering study systematically applies a stepwise model to differentiate pathogenic from non-pathogenic urinary isolates—an approach not previously described.

To determine whether a urinary isolate is pathogenic (commensal, colonizer, or direct pathogen) or non-pathogenic (commensal, colonizer, or contaminant) using a structured, stepwise approach.

This prospective, longitudinal, exploratory study was conducted over 24 months, starting in January 2022, at All India Institute of Medical Sciences Rishikesh, following approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. A stepwise model developed by the investigators was applied to assess the nature of the isolates. Data recorded using REDCap, and analysis was performed using SPSS Version 25.

A total of 275 consecutive patients aged over 18 years with positive urine cultures—initially treated with antibiotics based on microbiological and clinical assessment—were included. The stepwise model classified 90.54% of cases as pathogenic (commensals: 61.81%, colonizers: 14.18%, and direct pathogens: 14.54%) and 9.45% as non-pathogenic. The model showed that there could be a significant reduction in average hospital stay by over 13 days, along with saving approximately Rs. 981 per patient in antibiotic costs in non-pathogenic cohort.

This novel model identified that approximately one in ten urinary isolates, initially considered pathogenic and treated with antibiotics, were in fact non-pathogenic. The model is safe, feasible, and potentially valuable in resource-limited settings, warranting broader validation and implementation.

Core Tip: Differentiating true pathogens from colonizers or contaminants in urinary cultures remains a major challenge in clinical practice. This study presents a novel, stepwise model to assess the true pathogenicity of urinary isolates in hospitalized adults. The model identified nearly 10% of culture-positive cases—previously treated as infections—as non-pathogenic. This approach is safe, feasible, and potentially reduces unnecessary antibiotic use, especially in resource-limited settings.

- Citation: Yadav B, Pilania J, Kant R, Omar BJ, Saini S, Panwar VK, Bahurupi Y, Panda PK. Stepwise model to differentiate pathogenic from non-pathogenic organisms in urinary isolates: Effectiveness, safety, and feasibility prospective study. World J Exp Med 2025; 15(4): 109134

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v15/i4/109134.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.109134

The recognition of microorganisms isolated in cultures—particularly from non-sterile samples such as urine—poses a diagnostic dilemma for microbiologists and physicians alike[1]. The fundamental question is whether the identified microorganism is a true pathogen requiring immediate intervention, a harmless commensal, a colonizer that could become pathogenic under the right conditions, or a contaminant introduced during specimen collection.

A ‘pathogen’ is defined as an organism that fulfills Koch’s postulates, directly causing disease[2,3]. In contrast, non-pathogenic organisms are not associated with disease and thus do not require antimicrobial therapy[4,5]. Commensals live symbiotically with the host without causing harm[6], while colonizers may exist transiently or persistently without eliciting an immune response or clinical disease[7,8]. Contaminants are unintended microbes (bacteria, fungi, or viruses) introduced into a specimen during improper collection or handling[9,10].

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) represent a significant proportion of infectious disease diagnoses, and urine samples form a cornerstone of laboratory investigations. Although normally sterile, urine may acquire diverse microbial flora as it passes through the urethra, often including organisms such as Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus[11]. Microscopy, especially the detection of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, can support the diagnosis but cannot reliably distinguish infection from colonization or contamination in routine practice.

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria or colonization may lead to unnecessary antibiotic exposure and antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The global burden of AMR is a growing public health crisis, with an estimated 1.27 million deaths directly worldwide attributable to bacterial AMR in 2019. Urinary pathogens, particularly multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales, are major contributors due to the high frequency of antibiotic use in suspected UTIs. Misclassification of non-pathogenic isolates as pathogens remains common in real-world hospital settings[12,13]. Recent literature confirms the limitations of conventional UTI diagnostics[14]. There is a need for structured clinical-microbiological correlation models to guide antimicrobial use. By improving the accuracy of pathogen identification, a stepwise model can support antimicrobial stewardship efforts, reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure, and contribute to global AMR mitigation strategies[15].

This study proposes and evaluates a structured stepwise model to differentiate urinary pathogens from non-pathogens among hospitalized patients. By categorizing isolates based on clinical context, host factors, and laboratory indicators, the model aims to assist physicians in avoiding overdiagnosis and inappropriate antimicrobial use.

This prospective longitudinal exploratory study was conducted over 24 months (January 2022-December 2023) at All India Institute of Medical Sciences Rishikesh, following approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval No. 295/IEC/PGM/2022). The study involved collaboration between the Departments of General Medicine, Nephrology, and Urology.

Using a hypothesized frequency of 26.42% (± 5%), a 95% confidence level, and design effect of 1, the minimum sample size was calculated as 275 from a population of 3360 urine culture-positive cases over six months. During the study period consecutive positive urinary isolates were enrolled. A positive urine culture was defined as the growth of ≥ 105 CFU/mL of a single organism in a clean-catch midstream urine sample.

Adult patients (> 18 years) admitted at All India Institute of Medical Sciences Rishikesh. Positive urine culture reported by the microbiology department. Deemed urinary pathogens by microbiologist in the report. Deemed urinary pathogen by treating clinicians by giving antimicrobials to patients.

Patients who refused to participate. Unreachable for follow-up (e.g., lack of phone access). Exclusion by treating physician.

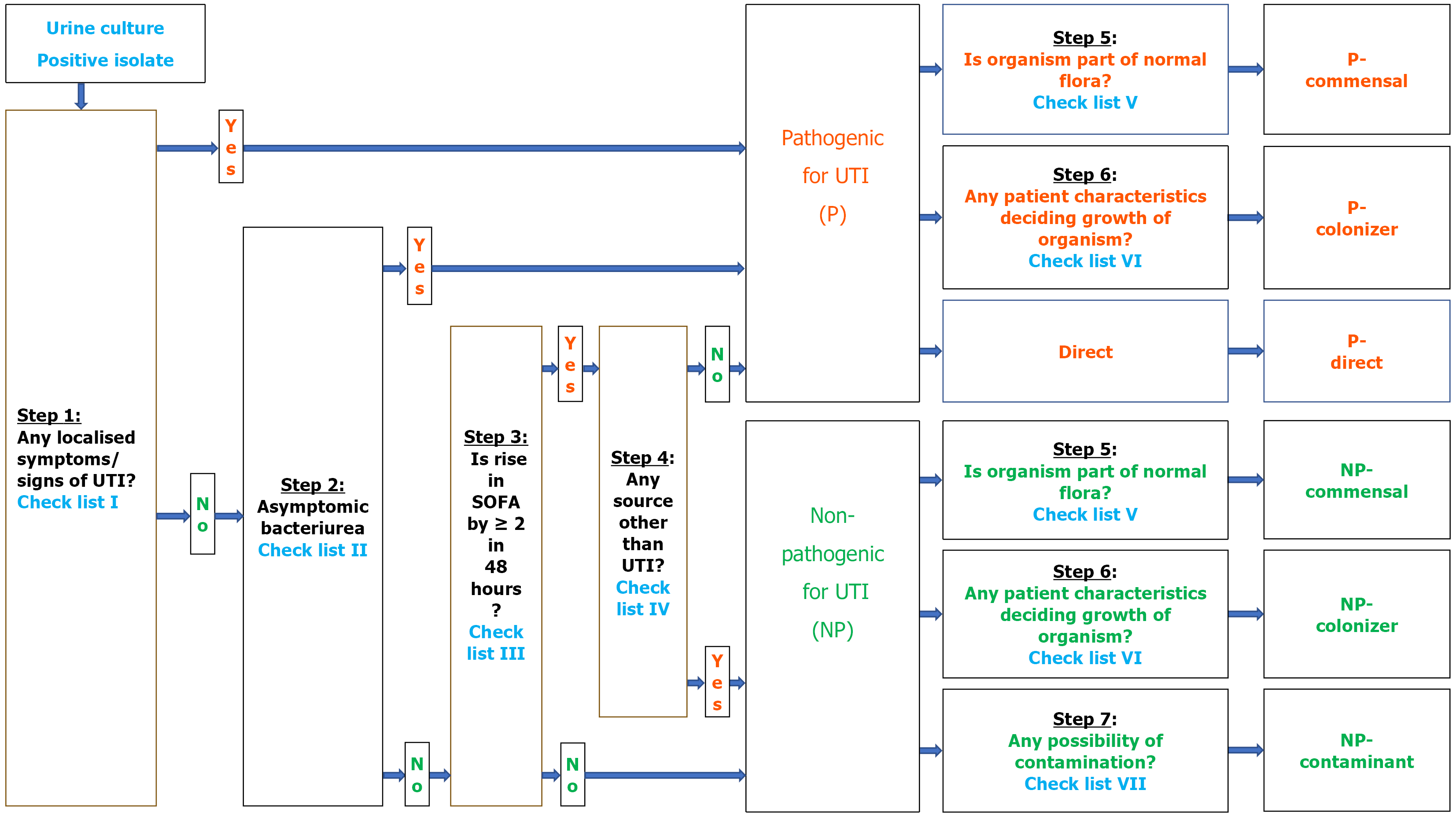

Whenever a urine culture tested positive and met inclusion criteria, the organism underwent a seven-step clinical-pathological algorithm to determine its pathogenicity by the investigator team as below (Figures 1 and 2).

Step 1: Evaluate local urinary symptoms (e.g., dysuria, urgency, hematuria) using Checklist I. If symptomatic → classify as pathogenic. If asymptomatic → proceed to Step 2.

Step 2: Evaluate for asymptomatic bacteriuria requiring treatment (Checklist II: e.g., pregnancy, urological procedure). If yes → classify as pathogenic. If no → proceed to Step 3.

Step 3: Check for sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score rise ≥ 2 within 48 hours (Checklist III). If no rise → classify as non-pathogenic. If rise present → proceed to Step 4.

Step 4: Investigate for non-UTI sources of SOFA rise (Checklist IV). If alternate source present → classify as non-pathogenic. If no alternate source → classify as pathogenic.

Step 5 and 6: Characterization of pathogenic organisms. Pathogenic organisms were further categorized as follows: (1) Normal flora status (Checklist V): → If part of flora → Pathogenic-commensal; (2) Host characteristics (Checklist VI): → If risk factors present → Pathogenic-colonizer; and (3) If neither → Direct pathogen.

Step 5 to 7: Characterization of non-pathogenic organisms. Non-pathogenic organisms were further classified as follows: (1) Step 5: If part of normal flora → Non-pathogenic commensal; (2) Step 6: If host characteristics present → Non-pathogenic colonizer; and (3) Step 7: If contamination indicators present (Checklist VII) → Non-pathogenic contaminant.

SOFA score was calculated using standard criteria based on six organ systems: Respiratory, cardiovascular, hepatic, coagulation, renal, and neurological parameters, as per established guidelines.

Once characterization was completed, patients were followed until discharge or 30 days, whichever occurred earlier, to determine the outcomes in form of all-cause mortality, duration of hospital stay, and antimicrobial costs.

Data were entered into an MS Excel sheet through REDCap and analyzed using SPSS software Version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to describe categorical variables in proportions or percentages, while continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations or medians with inter-quartile ranges. In inferential statistics, χ² tests were applied to compare proportions, and Student's t-tests were used to compare means. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess associations among different variables. With a confidence level of 95%, statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

The demographic analysis of 275 urinary isolates, as categorized by microbiologists and treating clinicians, revealed a notable age difference between male and female patients. The mean age for male patients was 50.57 years (SD = 17.36), while that of female patients was 42.80 years (SD = 14.26).

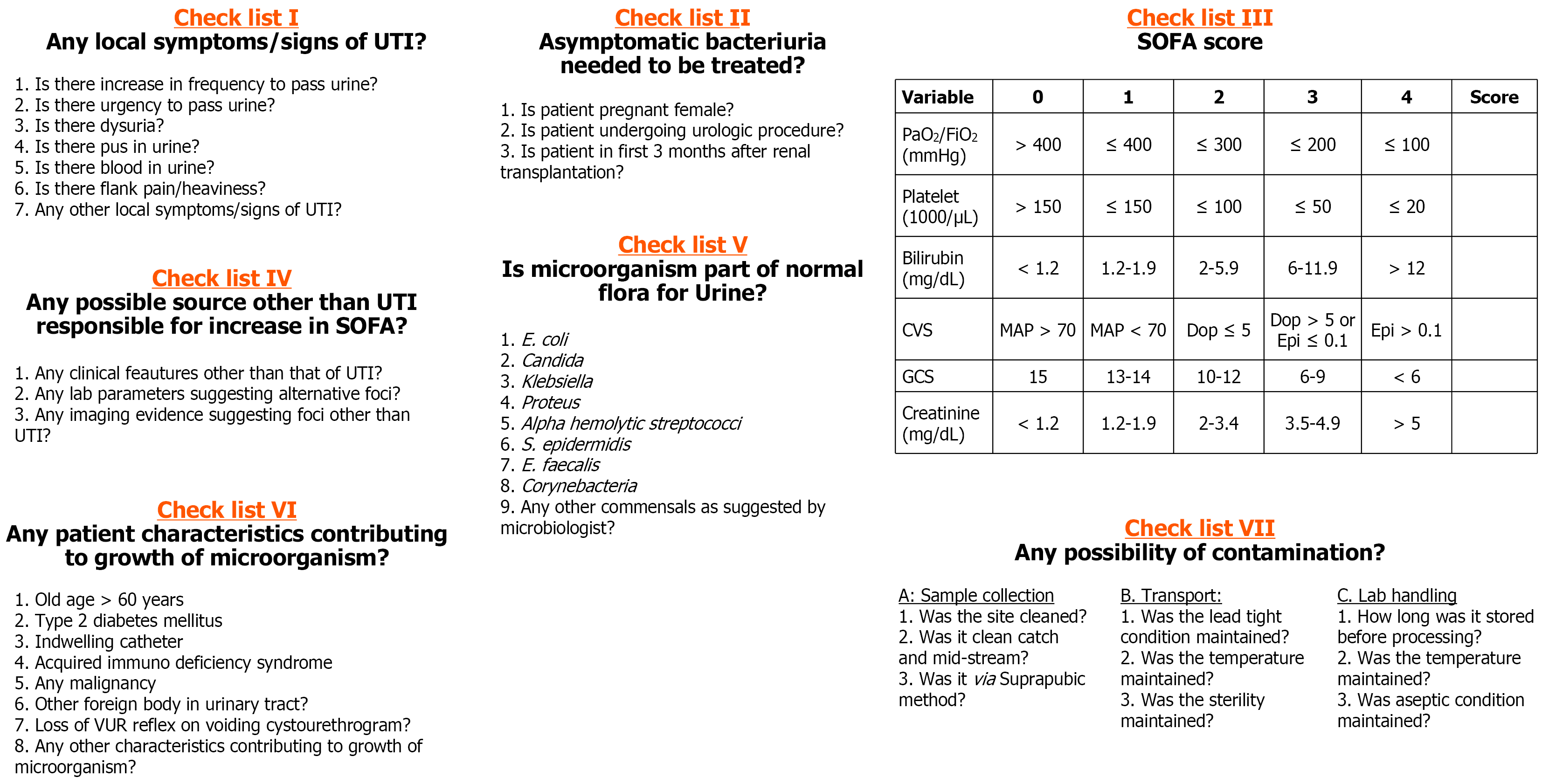

Using the algorithm-based (investigator-initiated) model, 249 isolates (90.54%) were classified as pathogenic. Among these, pathogenic-commensal organisms were most frequent (n = 170, 61.81%), followed by pathogenic-colonizer organisms (n = 39, 14.18%) and direct pathogens (n = 40, 14.54%).

Conversely, 26 isolates (9.45%) were categorized as non-pathogenic. These included non-pathogenic commensals (n = 19, 6.9%), non-pathogenic colonizers (n = 5, 1.81%), and non-pathogenic contaminants (n = 2, 0.72%). The final classification of organisms is shown in Figure 3.

A series of variables showed significant associations (P < 0.05) with the duration of hospitalization. These included: (1) Presence of localized UTI symptoms; (2) Increased urination and urgency; (3) Pyuria; (4) Absence of factors for asymptomatic bacteriuria; (5) Pathogenicity (as per the algorithm); (6) Nature and type of organism (commensal, colonizer, direct); (7) Presence of contaminants or direct organism; (8) Total duration of hospitalization (days); (9) Antibiotic cost (Rs.); and (10) Thirty-day mortality. Detailed associations are provided in Table 1.

| Parameters | Duration of hospitalization (days) | P value |

| Age (years) | Correlation coefficient (rho) = -0.06 | 0.302 |

| Age (years) | 0.682 | |

| 18-30 | 15.21 ± 15.13 | |

| 31-40 | 14.47 ± 10.44 | |

| 41-50 | 14.07 ± 9.87 | |

| 51-60 | 13.12 ± 9.46 | |

| 61-70 | 12.62 ± 8.64 | |

| 71-80 | 15.81 ± 14.51 | |

| 81-90 | 6.83 ± 1.72 | |

| > 90 | 13.00 ± 0 | |

| Gender | 0.221 | |

| Male | 12.98 ± 9.38 | |

| Female | 15.51 ± 13.76 | |

| Organism detected | 0.347 | |

| Escherichia coli | 12.05 ± 8.29 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 16.05 ± 10.89 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 14.76 ± 11.64 | |

| Candida spp. | 14.46 ± 17.37 | |

| Enterococcus faecium | 11.44 ± 5.76 | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 11.27 ± 5.14 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 11.67 ± 4.62 | |

| Others | 24.33 ± 16.74 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 8.00 ± 0 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 15.00 ± 0 | |

| Localized symptoms of UTI | 0.003 | |

| Yes | 14.66 ± 11.71 | |

| No | 10.33 ± 7.90 | |

| Symptom: Increased urination | 0.002 | |

| Yes | 15.76 ± 12.28 | |

| No | 12.92 ± 10.56 | |

| Symptom: Urination urgency | < 0.001 | |

| Yes | 16.15 ± 6.92 | |

| No | 13.48 ± 11.91 | |

| Symptom: Dysuria | 0.063 | |

| Yes | 13.06 ± 10.45 | |

| No | 15.10 ± 12.23 | |

| Symptom: Pyuria | 0.018 | |

| Yes | 18.65 ± 12.18 | |

| No | 3.50 ± 11.10 | |

| Symptom: Hematuria | 0.563 | |

| Yes | 10.43 ± 4.86 | |

| No | 14.02 ± 11.37 | |

| Symptom: Flank pain | 0.174 | |

| Yes | 17.97 ± 18.20 | |

| No | 13.38 ± 9.89 | |

| Factor for asymptomatic bacteriuria: Pregnancy | 0.911 | |

| Yes | 14.00 ± 11.31 | |

| No | 13.93 ± 11.29 | |

| Factor for asymptomatic bacteriuria: Urological procedure | 0.32 | |

| Yes | 9.92 ± 4.44 | |

| No | 14.11 ± 11.45 | |

| Factor for asymptomatic bacteriuria: Post renal transplant | No patients | |

| Factor for asymptomatic bacteriuria: None | 0.004 | |

| Yes | 10.25 ± 8.86 | |

| No | 14.42 ± 11.47 | |

| SOFA score change > 1 | 0.591 | |

| Yes | 15.04 ± 13.76 | |

| No | 13.89 ± 10.48 | |

| Pathogenicity (microbiologist) (pathogenic) | 13.93 ± 11.26 | |

| Pathogenicity (treating team) | 0.487 | |

| Pathogenic | 13.98 ± 11.31 | |

| Non-pathogenic | 9.33 ± 4.04 | |

| Pathogenicity (algorithm) | < 0.001 | |

| Pathogenic | 14.68 ± 11.55 | |

| Non-pathogenic | 6.77 ± 3.06 | |

| Commensal organism | 0.459 | |

| Yes | 13.17 ± 9.45 | |

| No | 15.59 ± 14.40 | |

| Colonizer organism | 0.212 | |

| Yes | 13.89 ± 16.10 | |

| No | 13.94 ± 10.13 | |

| Contaminant organism | 0.038 | |

| Yes | 3.50 ± 0.71 | |

| No | 14.01 ± 11.27 | |

| Direct organism | 0.006 | |

| Yes | 18.08 ± 12.21 | |

| No | 13.23 ± 10.97 | |

| Type of pathogenic organism | 0.05 | |

| Pathogenic-commensal | 13.88 ± 9.65 | |

| Pathogenic-colonizer | 14.67 ± 16.95 | |

| Pathogenic-direct | 18.08 ± 12.21 | |

| Type of non-pathogenic organism | 0.093 | |

| Non-pathogenic commensal | 6.84 ± 3.22 | |

| Non-pathogenic colonizer | 7.80 ± 2.28 | |

| Non-pathogenic contaminant | 3.50 ± 0.71 | |

| Type of any organism | < 0.001 | |

| Pathogenic-commensal | 13.88 ± 9.65 | |

| Pathogenic-colonizer | 14.67 ± 16.95 | |

| Pathogenic-direct | 18.08 ± 12.21 | |

| Non-pathogenic commensal | 6.84 ± 3.22 | |

| Non-pathogenic colonizer | 7.80 ± 2.28 | |

| Non-pathogenic contaminant | 3.50 ± 0.71 | |

| Patient outcome at discharge | 0.201 | |

| Discharged | 13.43 ± 10.07 | |

| Death | 22.80 ± 28.17 | |

| DOPR | 14.29 ± 2.75 | |

| LAMA | 23.00 ± 15.64 | |

| Duration of antibiotics (days) | Correlation coefficient (rho) = -0.06 | 0.318 |

| Cost of antibiotics (Rs) | Correlation coefficient (rho) = 0.13 | 0.036 |

| Thirty-day mortality | 0.017 | |

| Yes | 27.75 ± 29.56 | |

| No | 13.52 ± 10.09 |

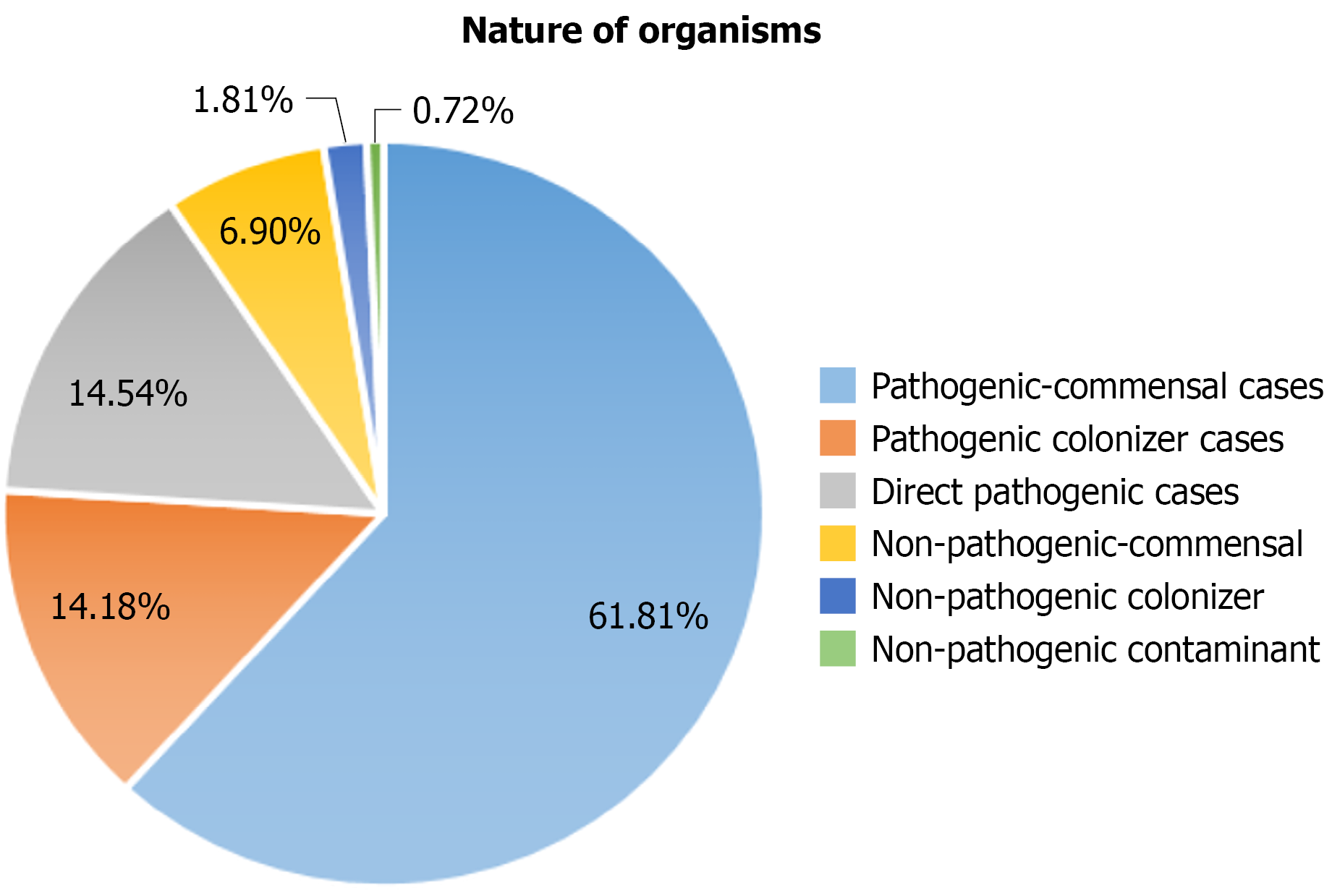

Each organism was further categorized based on pathogenicity using the algorithm (Figure 4): (1) Escherichia coli was predominantly pathogenic, with 76 of 81 cases (30.5% of all isolates); (2) Klebsiella pneumoniae showed a near-even split between pathogenic (n = 58, 23.3%) and non-pathogenic (n = 6, 9.3%), totaling 64 isolates; (3) Pseudomonas aeruginosa was entirely pathogenic (n = 54, 21.7%); (4) Candida spp. exhibited mixed pathogenicity—28 isolates (11.2%) were classified as pathogenic, while 13 (50% of Candida cases) were non-pathogenic; (5) Enterococcus faecium was largely non-pathogenic (14 of 16 cases); (6) Acinetobacter baumannii was entirely pathogenic (n = 11, 4.0%); and (7) Other organisms, including Enterobacter cloacae, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and miscellaneous others, were mostly classified as pathogenic.

In terms of clinical outcomes: (1) Discharge rates were high: 94.4% (n = 235) in the pathogenic group and 96.2% (n = 25) in the non-pathogenic group; (2) Mortality rates were 5.5% in the pathogenic group and 3.8% in the non-pathogenic group; (3) The mean length of hospital stay was 14.68 days for pathogenic cases, including 13.88 days for commensals, 14.67 days for colonizers, and 18.08 days for direct pathogens. For non-pathogenic cases, the mean stay was 13.81 days; (4) Antibiotic duration averaged 6.81 days (SD = 2.02) in pathogenic infections and 6.23 days (SD = 1.34) in non-pathogenic infections; and (5) The mean cost of antibiotics was Rs. 2424.44 for pathogenic cases and Rs. 981.15 for non-pathogenic cases.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically classify urinary isolates into pathogenic and non-pathogenic categories using a structured, algorithm-based approach. The model’s application to real-world clinical data provides clarity in distinguishing true infections from incidental or non-threatening microbial presences.

The study found that nearly 9.5% of all culture-positive urinary isolates were non-pathogenic, a crucial insight given that these organisms were often misinterpreted as pathogens in clinical practice. Such misclassifications can lead to overtreatment, increased hospital stays, and unnecessary antimicrobial costs, directly contributing to AMR.

Among pathogenic isolates, the most frequent category was pathogenic commensals (61.81%)—organisms that typically coexist harmlessly but can cause infection in immunocompromised or catheterized patients. This finding aligns with earlier evidence demonstrating opportunistic behavior of normal flora in altered host environments[6,7].

Pathogenic colonizers (14.18%), though asymptomatic at detection, pose risks under certain conditions such as instrumentation, comorbidities, or prolonged hospitalization[14]. Their identification highlights the importance of preventive surveillance and careful clinical correlation.

Direct pathogens (14.54%) such as Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae require immediate and specific antimicrobial therapy. Their accurate detection is vital to timely and effective treatment, especially in critically ill or septic patients[15].

In the non-pathogenic group, non-pathogenic commensals (6.9%) were the majority. These organisms, though frequently detected, do not cause disease and may provide protective benefits by limiting pathogenic overgrowth. Identifying and respecting this balance is central to microbiome preservation.

Non-pathogenic colonizers (1.81%) represent another diagnostic gray zone. Their presence highlights the importance of clinical judgment before initiating antimicrobials, particularly in asymptomatic patients.

Non-pathogenic contaminants (0.72%), although few, highlight systemic issues in sample collection. Minimizing these occurrences through strict aseptic protocols is essential to improve diagnostic accuracy[9].

The economic implications are substantial. In this cohort, unnecessary hospitalization averaged 13.81 days, and antibiotic costs totaled Rs. 981 per non-pathogenic patient. These expenditures could have been averted through algorithmic interpretation. A 2018 study by Daniel et al[16] also called for updated diagnostic strategies to reduce overtreatment in low-risk patients with bacteriuria[11]. Similarly, Bermingham et al[17] emphasized the economic burden of inappropriate antimicrobial use and hospital stays associated with asymptomatic infections.

The outcome-based analysis in Table 1 further validates the clinical and economic implications of accurate classification. Patients in the non-pathogenic group had significantly lower mortality (0%) and fewer complications compared to those with pathogenic isolates, suggesting that aggressive antimicrobial treatment may have been unnecessary. Moreover, the average hospital stay was notably shorter (13.81 days) and the antibiotic cost substantially lower (Rs. 981) in the non-pathogenic cohort. These findings highlight the potential healthcare savings and improved patient safety outcomes achievable by implementing this stepwise model for urinary culture interpretation. Inappropriate treatment of non-pathogens not only drives up direct costs but may also contribute to collateral damage such as microbiome disruption and increased AMR[11].

Unlike molecular techniques such as PCR or biomarker assays that detect the presence of microbial DNA/RNA or host response markers alone, our stepwise model integrates clinical assessment, quantitative culture data, and immune response parameters. This comprehensive approach enhances specificity in distinguishing true pathogens from colonizers or contaminants, offering a practical and cost-effective tool suitable for routine hospital settings where advanced diagnostics may not be readily available. The model’s reliance on routinely available clinical and laboratory parameters enhances its feasibility in primary care and low-resource settings, where access to advanced diagnostics is limited. By guiding rational antimicrobial use based on clinical-microbiological correlation, the model can support frontline providers in managing suspected UTIs more effectively.

This stepwise model also aligns with antimicrobial stewardship goals by reducing empirical treatment and promoting evidence-based prescribing[18,19]. Importantly, studies such as Silver et al[18] have noted that inappropriate treatment of culture-positive urine samples is a major cause of avoidable antibiotic use in hospitals.

Despite its novelty, the study has certain limitations: The data are drawn from a single region in India, which may limit global applicability. Reliance on subjective verbal responses and clinical documentation could introduce selection bias. Although structured, the model may oversimplify complex host-pathogen interactions. Additionally, organisms such as Candida spp. illustrate mixed pathogenicity, where clinical context determines whether they represent infection, colonization, or contamination—an aspect considered in our model.

This study lays the groundwork for further research on microbial risk stratification. Future efforts should focus on validating the model across varied healthcare settings and integrating biomarkers or rapid diagnostics to increase precision[10,15,18,20].

The study reinforces that nearly 10% of urinary isolates labeled as ‘culture positive’ may be non-pathogenic, leading to avoidable hospital stays and treatment costs. The stepwise categorization model not only enhances diagnostic clarity but also offers tangible benefits—reducing average hospital stay by over 13 days and saving approximately Rs. 981 per patient in antibiotic costs. Importantly, no adverse clinical outcomes were observed in the non-pathogenic group, underscoring the model’s safety. Integrating this model into routine microbiology workflows can drive targeted therapy, reduce overuse of antimicrobials, and strengthen hospital-based antimicrobial stewardship. Future multicenter studies are needed to validate the model’s effectiveness and facilitate its integration into clinical guidelines for antimicrobial stewardship.

We acknowledge the contributions of our mentors and colleagues whose insights and guidance significantly enriched this research. Our heartfelt thanks go to the study participants for their cooperation and contribution. Finally, we recognize the role of anonymous reviewers and prior researchers whose work laid the foundation for this study. Their collective efforts were instrumental in the successful completion of this work.

| 1. | Frank K. Microbiology in Clinical Pathology. Pathobiology of Human Disease. San Diego: Academic Press, 2014: 3237-3268. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sravanthi K, Sattiraju KS, Paul S, Nihal NG, Salunkhe S, Mane SV. Robert Koch: From Anthrax to Tuberculosis - A Journey in Medical Science. Cureus. 2024;16:e72955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fredricks DN, Relman DA. Sequence-based identification of microbial pathogens: a reconsideration of Koch's postulates. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:18-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 626] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mostowy S, Cossart P. From pathogenesis to cell biology and back. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:510-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pigłowski M. Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic Microorganisms in the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Host-pathogen interactions: basic concepts of microbial commensalism, colonization, infection, and disease. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6511-6518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | von Graevenitz A. The role of opportunistic bacteria in human disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1977;31:447-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. The damage-response framework of microbial pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chatterjee A, Abraham J. Microbial Contamination, Prevention, and Early Detection in Food Industry. In: Holban AM, Grumezescu AM, editors. Handbook of Food Bioengineering, Microbial Contamination and Food Degradation. Academic Press, 2018: 21-47. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Wullt B, Connell H, Röllano P, Månsson W, Colleen S, Svanborg C. Urodynamic factors influence the duration of Escherichia coli bacteriuria in deliberately colonized cases. J Urol. 1998;159:2057-2062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: when to screen and when to treat. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:367-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tomlinson E, Jones HE, James R, Cooper C, Stokes C, Begum S, Watson J, Hay AD, Ward M, Thom H, Whiting P. Clinical effectiveness of point of care tests for diagnosing urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2024;30:197-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pothoven R. Management of urinary tract infections in the era of antimicrobial resistance. Drug Target Insights. 2023;17:126-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, Saint S, Schaeffer AJ, Tambayh PA, Tenke P, Nicolle LE; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:625-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1219] [Cited by in RCA: 1308] [Article Influence: 81.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hickling DR, Sun TT, Wu XR. Anatomy and Physiology of the Urinary Tract: Relation to Host Defense and Microbial Infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2015;3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, Pahwa A, Soong C. An Implementation Guide to Reducing Overtreatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:271-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bermingham SL, Ashe JF. Systematic review of the impact of urinary tract infections on health-related quality of life. BJU Int. 2012;110:E830-E836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Silver SA, Baillie L, Simor AE. Positive urine cultures: A major cause of inappropriate antimicrobial use in hospitals? Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2009;20:107-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, Moran GJ, Nicolle LE, Raz R, Schaeffer AJ, Soper DE; Infectious Diseases Society of America; European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e103-e120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1631] [Cited by in RCA: 1981] [Article Influence: 132.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5:229-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 627] [Cited by in RCA: 1164] [Article Influence: 97.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/