INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is a prevalent chronic liver condition defined by hepatic fat accumulation in the context of metabolic risk factors[1]. It affects over 30% of the global adult population and has emerged as the most common cause of chronic liver disease, now representing a leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality worldwide[1,2]. MASLD is strongly associated with features of metabolic syndrome, including obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. In a subset of patients, the disease progresses to the inflammatory fibrotic subtype – metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis – which can evolve into advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma. This spectrum of severity underlines the clinical relevance of MASLD and the imperative for effective preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Its prevalence has been rising in parallel with the worldwide increases in obesity and type 2 diabetes, reflecting shared lifestyle and metabolic risk factors[3]. Certain high-risk groups are disproportionately affected; for instance, approximately two-thirds of individuals with type 2 diabetes have coexisting MASLD, highlighting the close pathophysiological link between metabolic dysfunction and liver steatosis[4]. Projections indicate that the burden of MASLD will continue to grow in the coming years, portending significant clinical and socioeconomic impacts if effective interventions are not implemented. Understanding the epidemiology of MASLD is therefore crucial for public health planning and reinforces the need for targeted approaches to curb this emerging epidemic[1].

Recent studies have illuminated a pivotal role of the gut–liver axis in MASLD pathogenesis, with gut microbial dysbiosis frequently observed in patients and strongly linked to disease development[3,5]. An imbalanced gut microbiota can increase intestinal permeability and expose the liver to microbial metabolites and endotoxins, thereby promoting hepatic inflammation, steatosis, and fibrogenesis. Accordingly, the gut microbiome has emerged as a promising therapeutic target in MASLD, and strategies aimed at modulating the microbiota (such as probiotics, prebiotics, or other dietary interventions) are being actively explored to alter the course of disease[5]. Harnessing these insights into gut–liver interactions offers novel opportunities for therapeutic intervention in MASLD, with the potential to complement existing lifestyle-based treatments and improve patient outcomes. This review aims to explore the mechanisms linking gut microbiota to MASLD and discuss emerging therapeutic opportunities.

GUT MICROBIOTA COMPOSITION

The human gut microbiota is a large and highly complex microbial community that is vital for host health. This means that within our gut we have trillions of these microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses) that belong to hundreds of species and two bacterial phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, together account for over 90% of all gut bacteria in healthy humans. Less abundant phyla are: Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia[6]. This core composition is stable and resilient, but diet, antibiotics, and lifestyle can modulate it. Normal gut flora are beneficial to the mammalian host through the digestion of indigestible parts of the diet, inducing a large portion of necessary nutrients (e.g., some vitamins), in addition to preventing colonization by pathogens and maturing the immune system[6,7]. The aforementioned collective contributions of the commensal microbiota are of great importance to maintaining the intestinal homeostasis, health, and ultimately human health as a whole. Fermentation of dietary fibers to short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): One of the key metabolic functions of the gut microbiota, with major end products being acetate, propionate, and butyrate[7].

SCFAs are indeed an energy source for colonocytes (mainly butyrate) but also act as signalling metabolites affecting the host's metabolism. They may help maintain gut barrier integrity and systemic energy balance by improving glucose and lipid metabolism, as well as regulating appetite through gut-brain hormonal axes. In addition to SCFAs, gut microbes produce a variety of different metabolites that are capable of modulating host physiology by influencing bile acids or producing vitamins (including vitamin K and the B-vitamins), thereby modulating bile acid signalling, intestinal motility, and nutrient status. The metabolism of microbiota thus participates in nutrient harvesting and energy homeostasis, and could eventually be related to body mass and metabolism. Low microbial efficiency of energy extraction has been suggested as a cause of obesity, but data on the relative contribution to obesity of a Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and energy harvest from the gut have varied[6,7]. A diet high in fiber promotes the in vivo growth of beneficial microbes that ultimately produce SCFA, while high-glucose or low-fiber diets promote conditions in which SCFA production and therefore the associated host metabolic benefits conferred by the microbiota may be impeded[8].

In addition, the gut microbiota are multidimensional immunomodulators of immune homeostasis apart from metabolism. The microbiota has an important role in the induction and specification, and functional tuning of the host immune system. Indeed, the mammalian immune system has diversified to live in harmony with a complex intestinal microbial environment, establishing tolerance to symbionts while retaining the ability to mount protective immunity to invading pathogens. Microbial colonization during early life promotes the expansion of gut-associated lymphoid tissues and the production of immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies, which coat bacteria and help localize microbes to the intestinal lumen and prevent translocation. Commensal microbes also stimulate epithelial cells and innate immune cells to secrete antimicrobial peptides (e.g., RegIIIγ) and mucus, and hence promote the intestinal barrier and restrict pathogen aggressiveness[7-9].

Additionally, microbial molecules (e.g., endotoxin, flagellin, and other microbe-associated molecular patterns) are sensed by pattern recognition receptors (e.g., Toll-like receptors) expressed by gut epithelial and immune cells, playing a role in maintaining the immune system in an equilibrated state. This establishes regulatory immune pathways — such as through the induction of regulatory T cells by some commensal-derived molecules — that suppress excess inflammation and promote tolerance to non-pathogenic antigens. In a healthy state, the gut microbiota plays a crucial role in shaping and fine-tuning the mucosal immune system, maintaining controlled inflammation and preventing infections, while simultaneously promoting immune tolerance to avoid autoimmunity. Dysbiosis, defined as an imbalance in the composition of the normal gut microbiota, can disrupt these homeostatic functions and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases. Altered microbiota profiles have been associated with several chronic conditions, including metabolic disorders such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and non-alcoholic (metabolic) fatty liver disease[7,10].

A well-known phenomenon on the level of the microbiome is decreased gut microbial diversity and altered community structure (ex., decreased levels of Bacteroidetes and increased Firmicutes and Proteobacteria) in the setting of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (NAFLD/MASLD), compared with healthy subjects[10]. These compositional changes carry functional consequences that promote disease progression. An unbalanced microbiota leads to insufficient SCFAs and increased metabolism of pro-inflammatory metabolites, and it deteriorates gut barrier function. The gut barrier can become leaky and permit translocation of bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) produced by gram-negative bacteria into the circulation, serving to drive hepatic inflammation via toll-like receptor 4 activation and other immune pathways. This interaction along the gut–liver axis is believed to drive the pathogenesis of NAFLD; signals derived from gut microbiota (including LPS and other metabolites) induce chronic liver inflammation, which also promotes insulin resistance and steatosis development in the host[11].

Dysbiosis is another process associated with the reduction of butyrate, in which, as in other intestinal diseases, high amounts of butyrate-producing species are diminished, resulting in decreased quantities of this important SCFA that upholds the healthy functionality of the intestinal barrier and lowers endotoxemia and systemic inflammation[10,11]. Collectively, these observations indicate that the gut microbial community and, in particular, its metabolic output are closely linked to immune homeostasis and metabolic regulation. In health, a balanced gut microbiota is used for nutrient metabolism, intestinal barrier strengthening, and immunity; in disease, dysbiosis induces inflammation and metabolopathy, and the microbiota is a modulator (and potential therapeutic target) for diseases such as MASLD/NAFLD[11].

DYSBIOSIS IN MASLD

Healthy individuals typically own a diverse gut microbial community dominated by beneficial taxa (e.g., Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes). In MASLD, studies report reductions in SCFA-producing bacteria (such as Ruminococcaceae, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii) and an overrepresentation of pro-inflammatory or opportunistic taxa (e.g., Proteobacteria like Escherichia spp.) as disease advances from simple steatosis to cirrhosis and HCC. These dysbiotic shifts lead to altered microbial metabolite profiles (SCFAs, bile acids, etc.) and heightened gut–liver axis signalling that promote intestinal permeability, inflammation, and fibrogenesis[12-14].

Gut microbiota plays a critical role in host metabolic homeostasis and immunity, and its imbalance (dysbiosis) is implicated in metabolic disorders such as MASLD[15]. One key function of the microbiota is nutrient metabolism – for example, fermenting dietary fibers to produce SCFAs like acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These SCFAs serve as energy substrates and signalling molecules that regulate glucose/Lipid metabolism and strengthen the intestinal epithelial barrier[16]. Dysbiosis in MASLD can disrupt this metabolic crosstalk: Patients often exhibit altered faecal SCFA profiles and a loss of important butyrate-producing bacteria, an imbalance linked to greater hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation. Such evidence suggests that a dysbiotic microbiome may fuel steatosis by both increasing energy harvest and reducing anti-inflammatory signals to the host[17].

The gut microbiota also exerts immunomodulatory functions that influence mucosal immunity. Commensal microbes help maintain immune tolerance in the gut–liver axis, for instance, by inducing regulatory T cells and stimulating IgA production that coats microbes and fortifies the mucus barrier. Dysbiosis undermines these defenses and skews immunity toward a pro-inflammatory state. Increased intestinal permeability in MASLD allows microbial antigens (e.g., LPS) to translocate into portal circulation, where they activate Toll-like receptors on Kupffer cells and other hepatic immune cells. This leads to heightened release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6)] that promote hepatocellular injury, steatohepatitis, and fibrosis in the liver[16].

Dysbiosis also disrupts the microbiota’s role in pathogen defense. A healthy microbiome confers “colonization resistance” by competing with pathogens and producing antimicrobial compounds, thereby limiting microbial translocation. In MASLD, an imbalance often emerges wherein potentially pathogenic commensals (pathobionts) overgrow at the expense of beneficial bacteria. For example, NAFLD/MASLD patients have been found to harbor increased abundances of Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae (such as Escherichia and Proteus species) alongside depletion of beneficial genera like Ruminococcus and Lactobacillus. This shift can elevate the luminal endotoxin load and impair mucosal barrier integrity, facilitating bacteria and their products to breach into circulation. Notably, such a breakdown of gut barrier defenses allows pathogen-associated molecular patterns to reach the liver, inciting continuous inflammation via pattern recognition receptors[18].

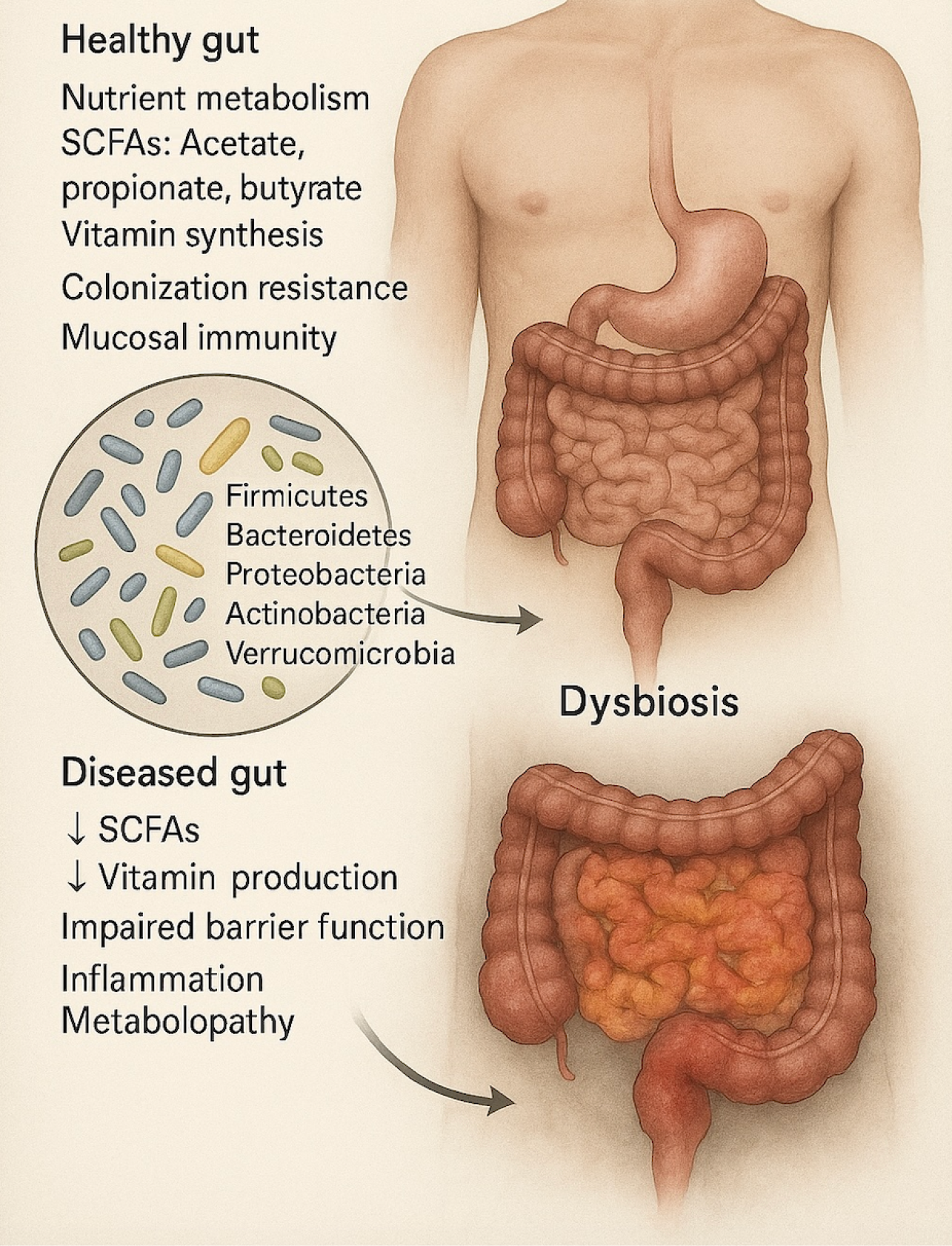

Dysbiosis in MASLD is characterized by disruption of the microbiota’s normal metabolic and immune functions, which contributes to disease progression. The loss of microbial diversity and beneficial metabolites (e.g., SCFAs), coupled with enhanced mucosal inflammation and permeability (“leaky gut”), creates a pro-steatotic and pro-inflammatory milieu in the liver as described in Figure 1[19]. Indeed, gut dysbiosis can disrupt the intricate gut–liver axis that ordinarily regulates metabolism and immunity, allowing translocation of inflammatory microbial products that drive hepatic fat deposition, inflammation, and fibrogenesis[15,20]. These insights highlight the gut microbiome as a pivotal factor in MASLD pathogenesis and a promising target for therapeutic intervention aimed at restoring metabolic and immune homeostasis.

Figure 1 Gut microbiota and dysbiosis-associated changes.

The illustration compares a healthy gut with a dysbiotic gut. The healthy gut is characterized by balanced microbial populations (e.g., Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia), which contribute to nutrient metabolism, production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): Acetate, propionate, butyrate), vitamin synthesis, colonization resistance, and mucosal immunity. Dysbiosis is marked by microbial imbalance, leading to decreased SCFAs and vitamin production, impaired gut barrier function, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction (metabolopathy). These changes disrupt intestinal homeostasis and are implicated in various diseases. SCFAs: Short-chain fatty acids.

MECHANISMS LINKING GUT MICROBIOTA TO MASLD PATHOGENESIS

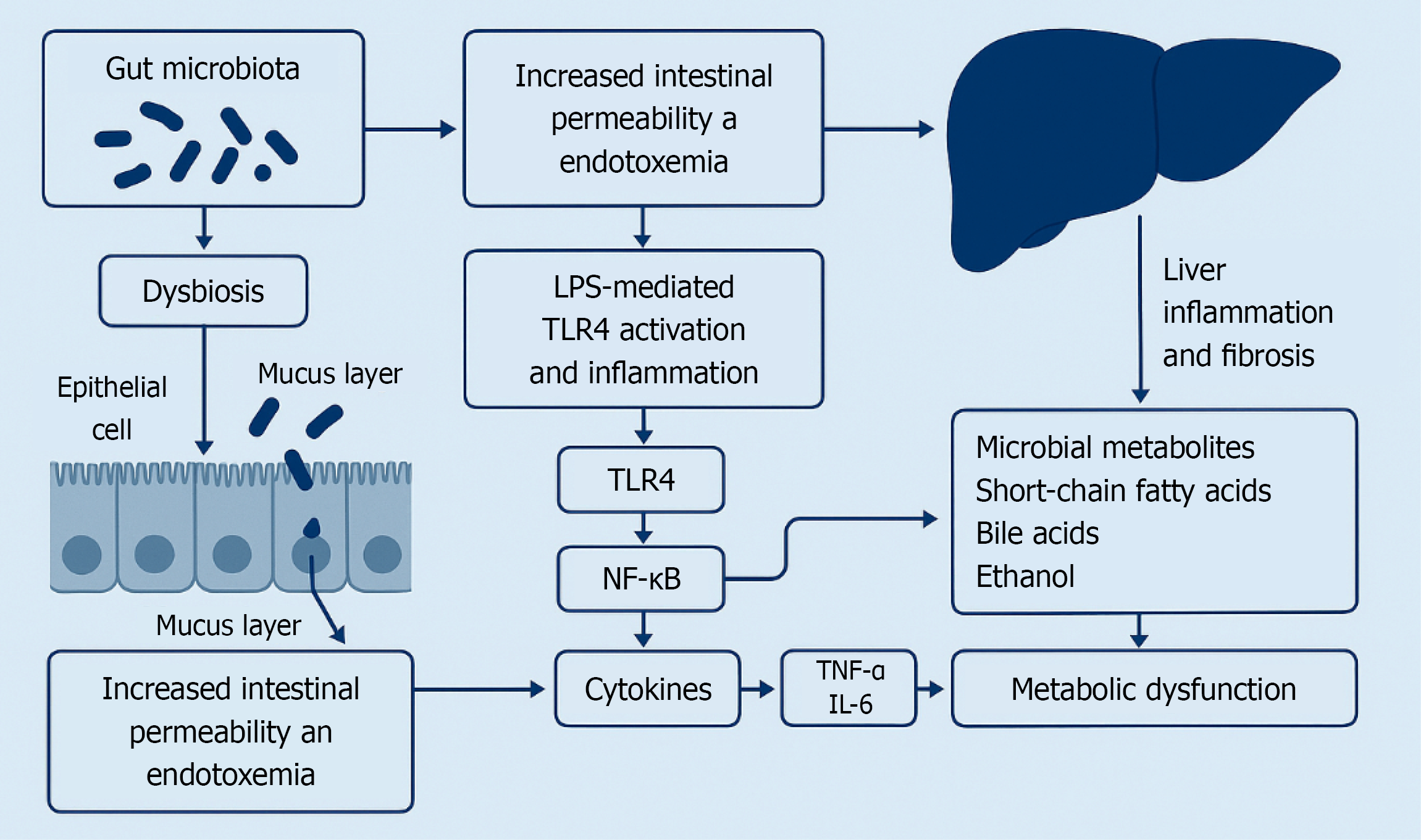

Increased Intestinal Permeability and Endotoxemia: Emerging evidence implicates gut microbiota dysbiosis as a key contributor to MASLD through disruptions in the gut–liver axis[21]. The liver is uniquely exposed to gut-derived factors because the majority of its blood supply comes from intestinal drainage via the portal vein[22]. In healthy individuals, the intestinal barrier (tight junctions and mucus layer) limits translocation of microbes and endotoxins; however, MASLD is associated with a “leaky gut” in which barrier integrity is compromised[23,24]. This increased intestinal permeability allows bacterial products like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to enter the portal circulation, a phenomenon termed metabolic endotoxemia[25]. Clinical studies report that circulating LPS levels are elevated in MASLD patients and correlate with hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress markers[24,25]. Notably, interventions that reinforce gut barrier function can attenuate experimental steatosis: For example, supplementation with butyrate (a microbial metabolite that strengthens tight junctions) reduced endotoxin translocation and protected mice from high-fat diet–induced steatohepatitis[26]. These findings underscore that increased intestinal permeability – and the resulting endotoxemia – is a pivotal mechanism linking dysbiosis to liver injury in MASLD.

LPS-mediated toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation and inflammation: Once gut-derived LPS reaches the liver, it activates TLR4 on Kupffer cells and other resident cells, driving innate immune responses[24,27]. LPS–TLR4 engagement triggers a MyD88-dependent signalling cascade that culminates in activation of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6[27,28]. This LPS-induced inflammatory milieu causes hepatocellular injury and recruits additional immune cells, promoting the progression from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis[21]. Animal models provide mechanistic proof: TLR4-deficient mice are protected from liver inflammation and injury in diet-induced NAFLD despite developing comparable steatosis, highlighting that endotoxin-driven TLR4 signaling is crucial for disease progression[27]. Moreover, Kupffer cell–derived cytokines can activate hepatic stellate cells and promote fibrogenesis, linking gut microbiota-derived LPS to liver fibrosis in advanced MASLD[21,28]. Chronic low-grade exposure of the liver to LPS due to dysbiosis fuels an inflammatory loop via TLR4 that exacerbates liver damage in MASLD as described in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Schematic summary of the bidirectional communication in the gut–liver axis.

Microbial Metabolites (SCFAs, Bile Acids, Ethanol): Beyond endotoxin, the gut microbiota influences MASLD through various metabolites that affect host metabolic and immune pathways. SCFAs produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber are one important example, with acetate, propionate, and butyrate serving as signalling molecules between the gut and liver[29,30]. SCFAs generally have beneficial effects: Butyrate and propionate strengthen the intestinal epithelial barrier, induce satiety hormones, and promote anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells, all of which can protect against hepatic steatosis[26,29]. In MASLD, dysbiosis often leads to a reduced abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria (e.g., Ruminococcaceae), resulting in lower levels of these protective metabolites[21,30]. Deficiency of SCFAs may contribute to disease by weakening the gut barrier and permitting inflammation. Conversely, restoring SCFAs has shown therapeutic potential in models: Supplementation of butyrate or propionate ameliorates high-fat diet–induced weight gain, insulin resistance, and liver fat accumulation, partly by activating hepatic AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and shifting metabolism toward fatty acid oxidation[30,31]. While the precise impact of SCFAs in human MASLD is still being studied, it is clear that shifts in microbial SCFA production can modulate the host’s inflammatory tone and energy balance, thereby influencing liver fat deposition.

Gut microbiota dysbiosis also perturbs bile acid (BA) metabolism, which in turn affects MASLD pathogenesis via BA-activated receptors. Normally, intestinal bacteria convert primary BAs (synthesized from cholesterol in the liver) into secondary BAs, which serve as ligands for the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor 5 (TGR5)[32]. FXR and TGR5 signalling maintain metabolic homeostasis: FXR activation induces hepatic fat oxidation and secretion of fibroblast growth factor 19, reducing de novo lipogenesis, while TGR5 activation on Kupffer cells inhibits NF-κB signalling to reduce inflammation[32,33]. Dysbiosis can alter the composition of the bile acid pool – for instance, by reducing the generation of certain secondary BAs – thereby impairing FXR/TGR5 activation and skewing liver metabolism toward fat accumulation and inflammation[33]. The importance of BA signalling is highlighted by pharmacotherapy: Activating FXR with obeticholic acid (a semi-synthetic BA) has been shown to improve NASH histological activity and fibrosis in clinical trials[34]. Thus, disruptions in the microbiota-BA axis (due to gut flora changes) can remove a critical check on hepatic fat deposition and inflammatory signalling in MASLD.

Another microbial metabolite implicated in MASLD is endogenous ethanol. Certain gut bacteria (such as some Klebsiella pneumoniae strains) produce ethanol as a fermentation byproduct, and patients with NAFLD/MASLD often exhibit higher blood ethanol levels despite no alcohol consumption[35,36]. This endogenous ethanol can exacerbate liver injury in a manner analogous to alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ethanol absorbed from the gut is metabolized in the liver to acetaldehyde and acetate; acetaldehyde directly damages hepatocytes and also impairs intestinal tight junctions, increasing gut permeability and facilitating further LPS entry into the portal circulation. Additionally, ethanol metabolism in hepatocytes induces CYP2E1 and generates reactive oxygen species, compounding oxidative stress and inflammation. In this way, dysbiosis-driven ethanol production creates a vicious cycle of barrier dysfunction and hepatic injury. Notably, one study identified a specific high-alcohol-producing bacterial strain in NAFLD patients that was sufficient to induce fatty liver when transplanted into mice, providing a clear example of a microbial metabolite directly causing MASLD[28,35,36]. Overall, microbial metabolites – from SCFAs and bile acids to ethanol – represent critical mechanistic links between gut dysbiosis and MASLD pathogenesis, operating through molecular pathways that govern intestinal permeability, inflammation, and hepatic metabolism.

GUT-LIVER AXIS: THE BIDIRECTIONAL COMMUNICATION

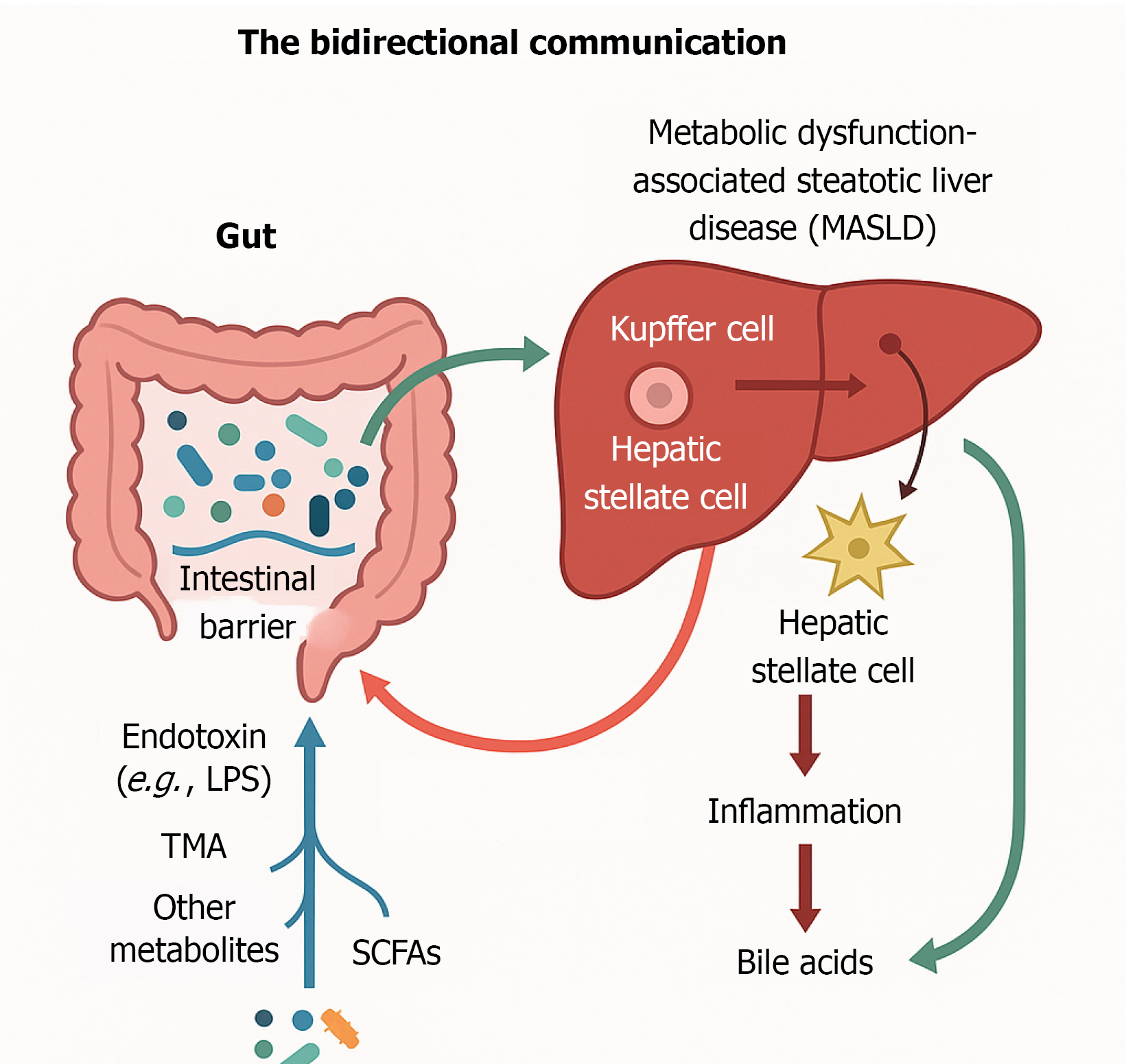

The gut–liver axis refers to the bidirectional communication network between the gut microbiota and the liver, and it plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of MASLD[37]. MASLD is increasingly recognized as a multi-system disorder rather than a liver-isolated disease, with gut dysbiosis and translocated microbial signals actively fueling the hepatic inflammation and metabolic derangements that characterize this condition. Anatomically, roughly two-thirds of the liver’s blood supply originates from the gastrointestinal tract via the hepatic portal vein, making this route the principal conduit by which gut-derived nutrients, microbial metabolites, and endotoxins reach the liver parenchyma[37]. This intimate vascular linkage means that any impairment in intestinal barrier integrity or shifts in the gut microbial community can have immediate hepatic consequences, as microbial products traversing the portal circulation stimulate liver cells and promote inflammatory pathways. Notably, the gut–liver axis is truly bidirectional: The liver communicates back to the gut largely through bile secretion—comprised of BAs, immunoglobulin A, and antimicrobial peptides—that enters the intestine via the biliary tract and helps shape the gut microbial milieu and barrier function[37,38].

Through this continuous cross-talk, a variety of microbial-derived molecules gain access to the liver and modulate hepatic physiology in the context of MASLD. Bacterial endotoxin (LPS) is a prime example: When intestinal permeability is increased (a “leaky gut”), LPS from Gram-negative bacteria translocates into portal blood and accumulates in the liver, where it can trigger the inflammatory cascade characteristic of steatohepatitis. In parallel, other gut microbiota metabolites and toxins—including trimethylamine (TMA), p-cresol, and hydrogen sulfide—are overproduced in dysbiotic states and can likewise reach the liver via the portal circulation. One important microbial metabolite is TMA, generated by the gut flora from dietary choline and carnitine; after absorption into the portal vein, TMA is converted in the liver to trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), a compound now linked to MASLD pathogenesis, with higher circulating TMAO levels correlating with greater hepatic steatosis and fibrosis[38]. Conversely, gut microbes also produce beneficial metabolites such as SCFAs that normally travel through the portal vein to the liver and exert anti-inflammatory or insulin-sensitizing effects; however, in MASLD patients, gut dysbiosis often leads to reduced SCFA production, potentially depriving the host of these protective signals. Thus, the portal vein serves as the highway for both deleterious and beneficial microbial products to influence liver health in MASLD[37].

Kupffer cells, which are liver macrophages, are stationed along the liver sinusoids (particularly in the periportal areas) so that they can intercept bacteria and other gut-derived toxins. Hepatic immune cells, like dendritic cells and monocytes, also express pattern recognition receptors that identify the fragments of microbes and their metabolites[39]. For example, the toll-like receptors (TLR4 and TLR9) of Kupffer cells recognize’ LPS and bacterial DNA, respectively, which activate inflammatory pathways proposed for LPS-induced hepatic inflammation already Kupffer cells. The triggering of these innate immune mechanisms invokes the synthesis and secretion of inflammatory mediators, more so cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which amplify inflammation and recruit more immune cells into the liver, which induces local inflammation while expanding the inflamed region, which in turn causes additional injury to the hepatocyte[40,41]. It further activates hepatic stellate cells and their transition to the fibrogenic myofibroblast stage, allowing them to secrete extracellular matrix compounds, thus connecting gut microbes to liver fibrosis. Kupffer cells undergo activation due to LPS or other bacterial components through TLR4, resulting in NF-κB moving to the nucleus, assembling inflammasome complexes (NLRP3) inside the cells, which increases the output of IL-1β and other cytokines. The hepatic immune system shifts the gut inflammatory responses into inflammation and tissue remodeling, which defines MASLD[42-44].

The gut–liver axis represents a bidirectional communication system where the liver influences gut homeostasis through BAs, which act as antimicrobial agents and signaling molecules, primarily via FXR activation to maintain gut barrier integrity and microbiota balance as described in Figure 3[45]. In MASLD, this protective mechanism is disrupted due to altered bile acid synthesis and cholestasis, promoting dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability[46]. Gut microbes further modulate the enterohepatic circulation by converting primary BAs into cytotoxic secondary BAs, which exacerbate hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress[47]. Consequently, a vicious cycle emerges—gut barrier dysfunction and microbial imbalance lead to liver injury, which then impairs bile production and worsens gut health[43]. This self-perpetuating loop underpins MASLD progression and highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting gut microbiota and bile acid signalling to restore gut–liver homeostasis and halt disease advancement[48].

Figure 3 The bidirectional gut–liver communication through bile acids.

Bidirectional gut–liver communication illustrates how microbial metabolites and endotoxins disrupt the intestinal barrier and drive hepatic inflammation, while bile acids regulate gut homeostasis.

MICROBIOTA-TARGETED THERAPIES FOR MASLD

One potential approach to managing MASLD is through the modulation of gut microbiota using probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics. Both probiotics and prebiotics have been evaluated as adjunct therapies for MASLD, yielding uneven but hopeful results. One recently published meta-analysis of thirty-four randomised trials found that probiotic, prebiotic, or synbiotic supplementation significantly improved the liver enzymes, inflammatory cytokines, and lipid profiles of patients diagnosed with fatty liver disease[49]. It is believed that these benefits stem from restoring a microbial balance, strengthening the gut barrier, and enhancing the production of SCFAs important for reducing hepatic inflammation. Even so, not all studies are aligned; variation in microbial strains, dosages, and patient populations has produced divergent results, and some reviews emphasise the heterogeneity and at times contradictory nature of the evidence[49]. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics hold promise for MASLD, but long-term definitive studies are essential to determine the effectiveness and intricate formulation challenges, responsive design variability.

CHALLENGES

The gut microbiome is implicated in MASLD, but a unified definition of “dysbiosis” specific to this disease remains elusive. Different studies often report divergent microbiota alterations in MASLD, reflecting inconsistencies in patient cohorts and methodologies[50]. A recent meta-analysis of 54 studies confirmed that MASLD (formerly NAFLD) is associated with reduced microbial diversity and a loss of beneficial butyrate-producing taxa, alongside an enrichment of pro-inflammatory bacteria, yet also highlighted substantial heterogeneity across populations[51]. These inconsistencies underscore the need for a standardized dysbiosis definition or set of microbial biomarkers in MASLD, which would enable more reliable comparisons across studies[50,51]. Establishing consensus on what constitutes MASLD-related dysbiosis is a critical first step to advance the field.

Interindividual variability and environmental influences further complicate the microbiome–MASLD relationship. Patients with MASLD differ widely in age, sex, ethnicity, diet, and co-morbid conditions, all of which can profoundly shape the gut microbiota[50]. Dietary habits are a major factor: For example, Western-style high-fat, high-sugar diets can induce a dysbiotic gut microbiome that promotes hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation, thereby exacerbating steatosis. In contrast, diets rich in fiber and complex carbohydrates tend to foster beneficial microbial communities that may protect the liver, a disparity illustrating how lifestyle influences can modulate MASLD outcomes[52]. Moreover, individuals respond differently to microbiota-targeted interventions; both probiotics and faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) have shown highly variable efficacy in MASLD, reflecting the personalized nature of gut microbiome dynamics. This pronounced interindividual variation means that a “one-size-fits-all” approach to correcting dysbiosis is unlikely to be effective, and it calls for strategies that account for each patient’s unique microbial and environmental context[53].

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

To address all these challenges, researchers are increasingly integrating multi-omics approaches to study MASLD, combining microbiome profiling with metagenomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics, and other data streams. Such holistic strategies can capture not only which microbes are present but also what functional capacities and metabolites they produce, thereby linking gut microbial changes to host metabolic pathways more directly[53,54]. Recent studies employing multi-omics and advanced machine-learning have identified more robust microbial signatures associated with MASLD by filtering out confounding factors: For instance, large-scale analyses have delineated distinct consortia of gut microbes and metabolites that are highly specific to NAFLD, separate from those seen in other metabolic disorders[55]. Integrative analyses have also begun to map how microbial metabolites (such as SCFAs or bile acids) interact with host gene expression and immune responses in the liver, offering insight into causal mechanisms of disease progression[53,54]. However, the integration of multi-dimensional datasets comes with significant technical and computational hurdles – handling the volume of data and avoiding false-positive associations requires sophisticated bioinformatic methods and large cohorts to achieve statistical power[53]. Despite these difficulties, the multi-omics approach is a promising avenue for discovering key microbe–host interactions and potential therapeutic targets that would not be evident from single-dataset studies alone[54,55].

One of the most exciting future directions is the development of microbiome-based personalized therapies for MASLD. As the gut–liver axis becomes better understood, the prospect of tailoring interventions to an individual’s microbiome profile is moving closer to reality[53]. In contrast to the current standard of care – largely generalized lifestyle modification and diet advice – a precision medicine approach would adapt dietary recommendations, prebiotic supplementation, or probiotic therapy to target each patient’s specific dysbiosis features[53,56]. For example, a patient lacking beneficial Ruminococcaceae might receive a targeted probiotic or dietary fiber intervention to restore butyrate production, whereas another with an overgrowth of endotoxin-producing Proteobacteria might benefit from bacteriophage therapy or antibiotics directed at those organisms. Early-stage trials of interventions like FMT in metabolic liver disease have produced mixed results, reinforcing that some patients respond while others do not – an outcome consistent with the need for personalization[53]. Going forward, researchers envision using gut microbiome signatures to stratify patients and predict who is most likely to benefit from a given therapy, thereby implementing truly individualized treatment algorithms[51,53].

CONCLUSION

In summary, the future of MASLD research and care is in refined benchmarking practices aligned with holistic approaches to the gut-liver axis. Striving toward consensus on MASLD dysbiosis and its individual-level determinants, alongside the integration of multi-omics, will provide robust information for the creation of microbiome-centric diagnostics and treatment frameworks. With these goals, the field is ready to translate microbiome science into clinical action through investment in large-scale, rigorously controlled studies and paradigm-shifting therapeutic interventions. The precision and multidisciplinary depth these frameworks afford not only advance our understanding of MASLD and its mechanisms but also enhance patient care by enabling the development of tailored therapeutic strategies.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Indonesia

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade A

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade A

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Cao Y, PhD, Associate Professor, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zheng XM