Published online Dec 20, 2024. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v14.i4.95147

Revised: July 19, 2024

Accepted: August 5, 2024

Published online: December 20, 2024

Processing time: 211 Days and 18.6 Hours

Autopsy is a medical procedure that consists of the examination of the corpse to determine the cause of death and obtain information on pathological conditions or injuries. In recent years, there has been a reduction in hospital autopsies and an increase in forensic autopsies.

To evaluate the utility of autopsy in the modern age and the discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses.

A retrospective observational study was conducted on the reports of all 645 hospital autopsies performed at Polyclinic of Bari from 2006 to 2021.

Group A, 2006-2009, 174 cases were studied: 58% male, 58% adults, 55% neo

The study of hospital autopsies reveals a 56.75% discrepancy between clinical diagnosis and autopsy, highlighting the importance of autopsies, especially for fetal and neonatal diseases, which represent 59% of cases.

Core Tip: The hospital autopsy is useful in the modern age, especially for the diagnosis of fetal and neonatal pathologies. Genetic and non-genetic diagnoses are important to future parents for subsequent pregnancies and can thus be studied.

- Citation: Salzillo C, Basile R, Cazzato G, Ingravallo G, Marzullo A. Value of autopsy in the modern age: Discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses. World J Exp Med 2024; 14(4): 95147

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v14/i4/95147.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v14.i4.95147

The term "autopsy" is derived from Greek and means "to see for oneself". There are two types of autopsy: hospital autopsy and forensic autopsy.

The first law authorizing human dissection was enacted in 1231 by Frederick II. In the 16th century, Andreas Vesalius initiated the modern study of anatomy with the publication of "De Humani Corporis Fabrica"[1]. Giovanni Morgagni correlated clinical symptoms with organic changes, introducing the anatomical-clinical concept, and published "De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis"[2].

In the 19th century, Karl von Rokitansky performed over 30000 autopsies and wrote the "Handbook of Pathological Anatomy"[3], while Rudolf Virchow, the founder of modern pathology, introduced detailed autopsy techniques[4]. Maurice Letulle described the technique of mass organ removal[5], and Albrecht Ghon introduced the technique of en bloc removal.

Over the last decades, there has been a significant decrease in the number of hospital autopsies and an increase in judicial autopsies[6]. This phenomenon may be due to various factors, including changes in medical practices, economic issues and the evolution of diagnostic techniques. Hospital autopsies are used as a tool to improve the quality of care and diagnostic accuracy. However, their utilization has declined due to budget constraints and growing confidence in imaging technologies[7,8]. Forensic autopsies are performed to determine the cause of death for forensic purposes. Their frequency has increased due to a greater emphasis on medico-legal responsibility and the need for thorough investigations in cases of suspicious or violent death[9,10]. This underlines how our society has an interest in the legal aspect rather than in knowing the cause of death.

In this study, we aimed to analyze 645 hospital autopsy cases from 2006 to 2021 retrieved from the digital archive of the Pathology Unit, Department of Precision and Regenerative Medicine and Ionian Area, Polyclinic of Bari, to study the rate of concordance between clinical and autopsy diagnosis and evaluating whether the execution of hospital autopsies is helpful in the modern age.

In our retrospective observational study, we analyzed the autopsy case history of the Pathology Unit, Department of Precision and Regenerative Medicine and Ionian Area, Polyclinic of Bari.

We used the digitalized archive of autopsy reports between 2006 and 2021 for a total of 645 cases, and all cases in the archive were included in the study.

The 645 cases were divided into groups of 4 years to make the samples uniform and comparable: group A: 2006-2009 of 174 cases, group B: 2010-2013 of 119 cases, group C: 2014-2017 of 168 cases, and group D: 2018-2021 of 184 cases.

Each subgroups was divided by age: Fetus < 180 days or < 6 months gestational age, infant/newborn 1 year of age, child/adolescent 1-16 years of age, and adult > 16 years of age.

The total divisions into subgroups included the following: Sex, age, specialty, autopsy diagnosis, and correlation between clinical and autopsy diagnosis.

To analyze the pathological diagnosis, we grouped the cause of death into: Cardiovascular, infectious, miscellaneous, neoplastic, placental, pulmonary, and syndromes/malformations.

Finally, we analyzed the discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses.

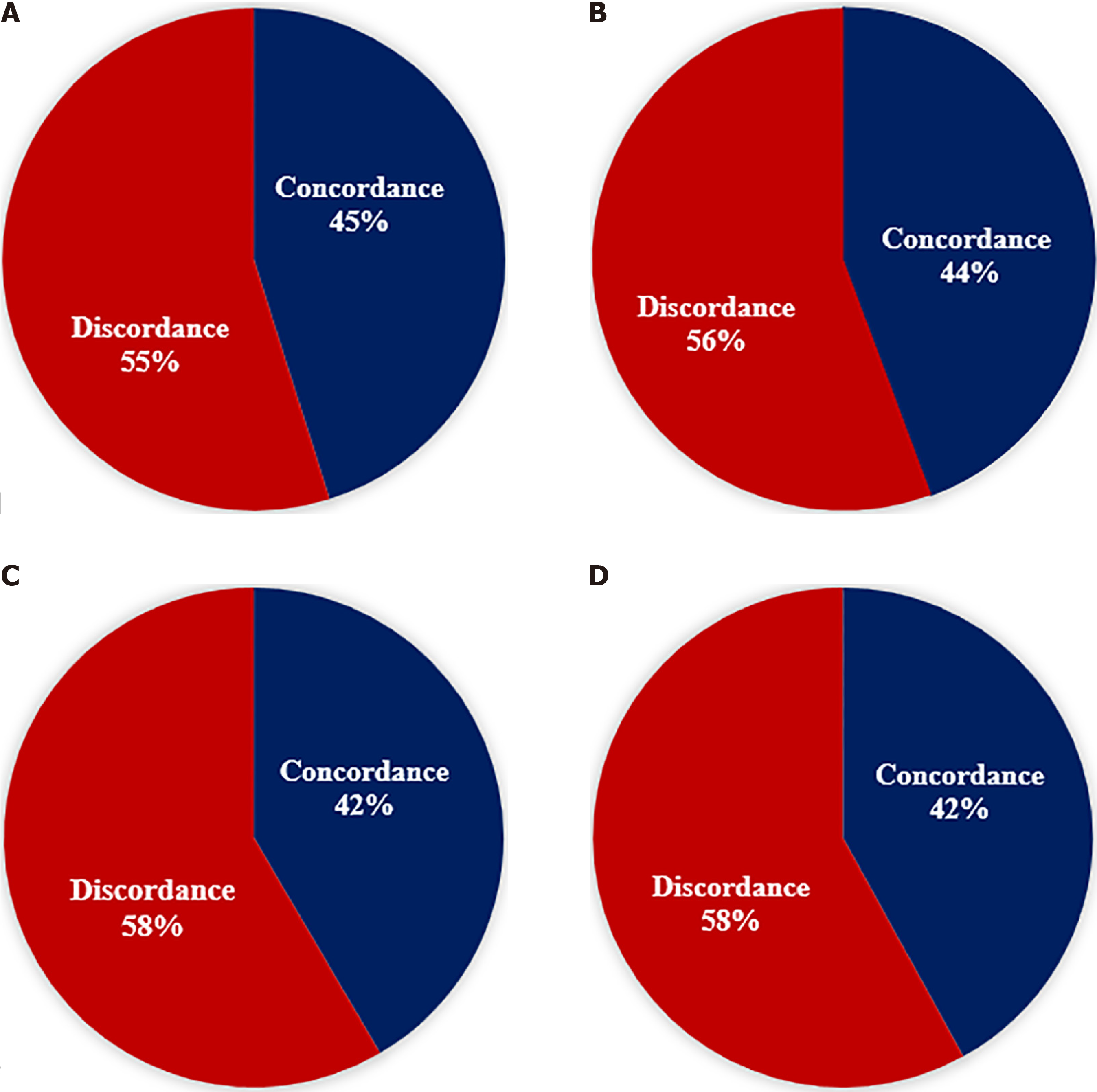

Out of 174 cases in group A (Table 1), 58% were male, 41% female, and 1% undefined, of which 58% were adults, 1% children, 29% infants, and 12% fetuses. Out of these 174, the specialty were: neonatology 55%, gynecology 19%, internal medicine 10%, external 7%, and other departments 9%. The cause of death was classified as pulmonary disease in 23%, syndromes and/or malformations 10%, infections 8%, cardiovascular diseases 6%, placental disease 4%, neoplasms 4%, and miscellaneous 45%. In 55% of the analyzed cases, there was discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses (Figure 1A).

| Group A | Sex | Age | Specialty | Autopsy diagnosis | Discrepancy |

| 174 cases, 2006-2009 | 58% male, 41%female, 1% undefined | 58% adults, 29% infants, 12% fetuses, 1% children | 55% neonatology, 19% gynecology, 10% internal medicine, 9% others, 7% external | 23% pulmonary, 10% syndromes/malformations, 8% infections, 6% cardiovascular, 4% placental, 4% neoplasms, 45% miscellaneous | 55% |

Group B (Table 2) comprised 119 cases; 51% male, 48% female, and 1% undefined, of which 31% were adults, 6% children, 46% infants, and 17% fetuses. The specialty of the origin of the deceased was 48% neonatology, 19% gynecology, 10% cardiac surgery, 12% general surgery, 4% neurology, and 7% others. The cause of death was categorized as 25% pulmonary diseases, 15% cardiovascular diseases, 11% syndromes and/or malformations, 9% infectious diseases, 3% neoplasms, 1% placental pathology, and 36% miscellaneous. In 56% of the cases, a discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses was observed (Figure 1B).

| Group B | Sex | Age | Specialty | Autopsy diagnosis | Discrepancy |

| 119 cases, 2010-2013 | 51% male, 48% female, 1% undefined | 31% adults, 46% infants, 17% fetuses, 6% children | 48% neonatology, 19% gynecology, 12% general surgery, 10% cardiac surgery, 7% others, 4% neurology | 25% pulmonary, 15% cardiovascular, 11% syndromes/malformations, 9% infectious, 3% neoplasms, 1% placental, 36% miscellaneous | 56% |

Group C (Table 3) comprised 168 cases, of which 50% were male and 50% female; 26% were adults, 1% were children, 37% infants, and 36% fetuses. The origin of the deceased was 30% gynecology, 25% neonatology, 17% cardiac surgery, 6% emergency room, 5% general surgery, 4% from other regional hospitals, and 13% others. The cause of death was classified as 24% pulmonary diseases, 15% cardiovascular diseases, 11% syndromes and/or malformations, 6% placental pathology, 3% infections, 2% neoplasms, and 39% miscellaneous. In 58% of the cases, there was a discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses (Figure 1C).

| Group C | Sex | Age | Specialty | Autopsy diagnosis | Discrepancy |

| 168 cases, 2014-2017 | 50% male, 50% female | 37% infants, 36% fetuses, 26% adults, 1% children | 30% gynecology, 25% neonatology, 17% cardiac surgery, 13% others, 6% emergency room, 5% general surgery, 4% external | 24% pulmonary, 15% cardiovascular, 11% syndromes/malformations, 6% placental, 3% infections, 2% neoplasms, 39% miscellaneous | 58% |

Group D (Table 4) comprised 184 cases; 56% male, 43% female, and 1% undefined; 38% were adults, 3% children, 26% infants, and 33% fetuses. Of these 184 cases, the specialty of origin was 32% gynecology, 21% other regional hospitals, 21% neonatology, 14% emergency department, and 12% others. In 27% of patients, the cause of death involved pulmonary diseases, 23% cardiovascular diseases, 6% syndromes and/or malformations, 5% placental disease, 4% infections, 2% neoplasms, and 33% miscellaneous. In 58% of the cases, there was a discrepancy between clinical and pathological diagnoses (Figure 1D).

| Group D | Sex | Age | Specialty | Autopsy diagnosis | Discrepancy |

| 184 cases, 2018-2021 | 56% male, 43% female, 1% undefined | 38% adults, 33% fetuses, 26% infants, 3% children | 32% gynecology, 21% neonatology, 21% external, 14% emergency room, 12% others | 27% pulmonary, 23%cardiovascular, 6% syndromes/malformations, 5% placental, 4% infections, 2% neoplasms, 33% miscellaneous | 58% |

From our study it is evident that sex distribution has remained constant over time. In fact, the percentage of males showed only slight variations, going from 58% in group A to 56% in group D; whereas the percentage of females remained stable, fluctuating between 41% and 50%. This stability suggests that there were no significant changes in the sex distribution over the study period.

We observed an important change in age distribution. The percentage of newborns and fetuses increased over time, with a peak in Group C where newborns were 37% of cases and fetuses were 36% of cases; however, the percentage of adults significantly decreased, from 58% in Group A to 38% in Group D. This trend demonstrates the growing attention of autopsies to pediatric and neonatal cases in recent years.

Neonatology is one of the main specialties involved in autopsies, but the percentage fell from 55% in group A to 21% in group D. In contrast, gynecology had a significant increase, becoming the predominant specialty in group D with 32%. This change reflects possible changes in clinical practices and autopsy patient populations.

Lung and cardiovascular diseases consistently have high rates as causes of death across all groups. However, diagnoses classified as “miscellaneous” made up a significant proportion in each group, with a slight decrease from 45% in Group A to 33% in Group D. This broad and generic category of diagnoses could include a variety of conditions that do not fit into major disease categories, likely reflecting the complexity and diversity of autopsy cases examined.

The percentage of discrepancy between the clinical diagnosis and the autopsy diagnosis remained high and constant throughout the study period, with a variation between 55% and 58%. This discrepancy highlights the importance of autopsies as a crucial diagnostic tool, underscoring the limitations of clinical diagnoses and the utility of autopsy in revealing conditions not identified during life.

By analyzing the 645 hospital autopsies (Table 5), we observed a predominance of 53.75% males, 59% newborns and fetuses. The most frequent specialty of origin was 37.25% neonatology and 25% gynecology. The cause of death in our study was primarily pulmonary diseases followed by cardiovascular diseases, and the discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses was over 56.75%.

| Group | Sex | Age | Specialty | Autopsy diagnosis | Discrepancy |

| A + B + C + D = 645 cases, 2006-2021 | 53.75% male, 45.5% female, 0.75% undefined | 38.25% adults, 34.5% infants, 24.5% fetuses, 2.75% children | 37.25% neonatology, 25% gynecology, 10.25% others, 8% external, 6.75% cardiac surgery, 5% emergency room, 4.25% general surgery, 2.5% internal medicine, 1% neurology | 24.75% pulmonary diseases, 14.75% cardiovascular diseases, 9.5% syndromes/malformations, 6% infections, 4% placental disease, 2.75% neoplasms, 38.25% miscellaneous | 56.75% |

Our study highlights that hospital autopsies were mainly performed in fetuses and infants, and the requirement of autopsy in adults was progressively reduced.

The decrease in hospital autopsies in adult patients is probably due to the excessive trust in medical diagnostic technology, whereby it is believed that the autopsy does not provide any additional information that is not already known at the time of death[11].

Although some studies have underlined the importance of carrying out a hospital autopsy[6,11,12], medical doctors often do not recognize the importance and therefore do not explain the advantages to the deceased’s relatives. Autopsy is a fundamental tool for understanding pathological processes, the effectiveness of treatments, the correct diagnostic approaches, and for preventing medical errors and supporting public health[13,14].

In a study conducted in Sweden by Friberg et al[15] on 2410 hospital autopsies of adult patients, there was an overall reduction in the request for autopsy examination with prevalence of cardiovascular disease as the cause of death, and with a discrepancy of more than 30% between clinical diagnosis and autopsy. The authors highlighted how the hospital autopsy provides information about the disease and cause of death that is likely unknown to the doctor and presumably to the relatives of the deceased and explained how this can have a negative impact on public health[15,16].

In a prospective cohort study, Latten et al[17] investigated the relationship between clinical cause of death, a history of cancer, and the rate of medical autopsies. The authors observed that the autopsy rate was positively correlated with the number of causes of death, suggesting a higher value of interest in autopsies in complex medical cases. According to the authors, healthcare and individuals would benefit from an increase in post-mortem investigations[17].

In their study, O'Rahelly et al[18] observed a 40% reduction in the autopsy rate and other studies in the literature[9,19,20].

One factor that can have a positive influence on reducing the performance of hospital autopsies is the communication by the doctor of the importance of the autopsy to provide clarification of the cause of death[21], especially in sudden death in fetuses, infants and young people, from cardiac or non-cardiac causes and from genetic or non-cardiac causes.

Studies in the literature[22-25] report that male infants and children tend to have higher mortality rates than females, which may be explained by the greater vulnerability of males to perinatal complications, congenital diseases and genetic syndromes. In particular, male newborns are more likely to be born prematurely with low birth weight and to develop respiratory distress syndrome, as they have slower lung maturation than females, making them more susceptible to respiratory problems and consequently significantly increases the risk of neonatal mortality. Furthermore, another crucial aspect is the genetic vulnerability of males due to the presence of only one X chromosome compared to XX females, which makes them more susceptible by increasing mortality. In addition, it is important to underline that stillbirth represents a dramatic experience, not only for parents, but also for professionals, especially if it occurs in the last weeks of gestation.

Interestingly, in our case history, the major cause of death was pulmonary pathologies. This result may be due to the fact that lung pathologies are often subtle in their clinical manifestation and are among the pathologies that predominantly manifest themselves in long-term hospitalizations in patients hospitalized for another pathology, but also that the cause of death is often not clear and therefore clinicians are more sensitive to requesting a hospital autopsy. Therefore, it is clear that the hospital autopsy is still useful in the modern age to evaluate the clinical diagnostic accuracy. It is particularly important for fetuses and newborns to identify the various causes of death, both genetic and otherwise, and to be able to help future parents plan for subsequent pregnancies[26]. From a public health perspective, the autopsy can become a preventive tool for family members and the community and play a role in grieving[27].

Our study and others demonstrate that hospital autopsies have significantly decreased in recent years despite being a fundamental tool for understanding causes of death and for improving medical practices. Consequently, this reduction has resulted in a loss of valuable clinical information that could contribute to medical training, scientific research and improving the quality of care. Effective strategies to increase autopsy rates should involve raising awareness of healthcare personnel, patients and hospital policies.

A crucial first step is to invest in the continuous education and training of healthcare personnel, who must be co

Additionally, hospital policies are instrumental in providing guidelines and recommendations to establish mandatory autopsies in specific circumstances, such as in cases of sudden deaths.

In conclusion, the study of hospital autopsies at the Polyclinic of Bari shows that the discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnosis is 56.75%. Moreover, the hospital autopsy is still useful in the modern age, especially for the diagnosis of fetal and neonatal pathology who together account for 59% of autopsies, so that genetic and non-genetic diagnoses can be studied to help future parents for subsequent pregnancies. Focusing on the problems of stillbirth means ensuring adequate support for mothers and relatives, who are all too often left alone to face this traumatic event. Furthermore, analysis of hospital autopsy data over time reveals significant changes in patient demographics, medical specialties involved and causes of death. Despite these changes, the discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses remains an ongoing problem, underscoring the crucial importance of autopsies to improve diagnostic accuracy and the quality of medical care.

| 1. | Cambiaghi M. Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564). J Neurol. 2017;264:1828-1830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ghosh SK. Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771): father of pathologic anatomy and pioneer of modern medicine. Anat Sci Int. 2017;92:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Prichard R. Selected items from the history of pathology: karl von rokitansky (1804-1878). Am J Pathol. 1979;97:276. |

| 4. | Tan SY, Brown J. Rudolph Virchow (1821-1902): "pope of pathology". Singapore Med J. 2006;47:567-568. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Magnon R. [Maurice Letulle (1853-1929]. Rev Infirm. 2009;45. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Sblano S, Arpaio A, Zotti F, Marzullo A, Bonsignore A, Dell'Erba A. Discrepancies between clinical and autoptic diagnoses in Italy: evaluation of 879 consecutive cases at the "Policlinico of Bari" teaching hospital in the period 1990-2009. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2014;50:44-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shojania KG, Burton EC. The vanishing nonforensic autopsy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:873-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lundberg GD. Low-tech autopsies in the era of high-tech medicine: continued value for quality assurance and patient safety. JAMA. 1998;280:1273-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Turnbull A, Osborn M, Nicholas N. Hospital autopsy: Endangered or extinct? J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:601-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McPhee SJ, Bottles K. Autopsy: moribund art or vital science? Am J Med. 1985;78:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Scarl R, Parkinson B, Arole V, Hardy T, Allenby P. The hospital autopsy: the importance in keeping autopsy an option. Autops Case Rep. 2022;12:e2021333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hamza A. Perception of pathology residents about autopsies: results of a mini survey. Autops Case Rep. 2018;8:e2018016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Esteban A, Fernández-Segoviano P. The autopsy as a tool to monitor diagnostic error. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:343-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xiao J, Krueger GR, Buja LM, Covinsky M. The impact of declining clinical autopsy: need for revised healthcare policy. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:41-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Friberg N, Ljungberg O, Berglund E, Berglund D, Ljungberg R, Alafuzoff I, Englund E. Cause of death and significant disease found at autopsy. Virchows Arch. 2019;475:781-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Veress B, Alafuzoff I. A retrospective analysis of clinical diagnoses and autopsy findings in 3,042 cases during two different time periods. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:140-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Latten BGH, Kubat B, van den Brandt PA, Zur Hausen A, Schouten LJ. Cause of death and the autopsy rate in an elderly population. Virchows Arch. 2023;483:865-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | O'Rahelly M, McDermott M, Healy M. Autopsy and pre-mortem diagnostic discrepancy review in an Irish tertiary PICU. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:3519-3524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lindström P, Janzon L, Sternby NH. Declining autopsy rate in Sweden: a study of causes and consequences in Malmö, Sweden. J Intern Med. 1997;242:157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Latten BGH, Overbeek LIH, Kubat B, Zur Hausen A, Schouten LJ. A quarter century of decline of autopsies in the Netherlands. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34:1171-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vignau A, Milikowski C. The autopsy is not dead: ongoing relevance of the autopsy. Autops Case Rep. 2023;13:e2023425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ingemarsson I. Gender aspects of preterm birth. BJOG. 2003;110 Suppl 20:34-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rysavy MA, Horbar JD, Bell EF, Li L, Greenberg LT, Tyson JE, Patel RM, Carlo WA, Younge NE, Green CE, Edwards EM, Hintz SR, Walsh MC, Buzas JS, Das A, Higgins RD; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network and Vermont Oxford Network. Assessment of an Updated Neonatal Research Network Extremely Preterm Birth Outcome Model in the Vermont Oxford Network. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:e196294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Garite TJ, Combs CA, Maurel K, Das A, Huls K, Porreco R, Reisner D, Lu G, Bush M, Morris B, Bleich A; Obstetrix Collaborative Research Network. A multicenter prospective study of neonatal outcomes at less than 32 weeks associated with indications for maternal admission and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:72.e1-72.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tietzmann MR, Teichmann PDV, Vilanova CS, Goldani MZ, Silva CHD. Risk Factors for Neonatal Mortality in Preterm Newborns in The Extreme South of Brazil. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Xu Y, Cheng C, Zheng F, Saiyin H, Zhang P, Zeng W, Liu X, Liu G. An audit of autopsy-confirmed diagnostic errors in perinatal deaths: What are the most common major missed diagnoses. Heliyon. 2023;9:e19984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | McPhee SJ, Bottles K, Lo B, Saika G, Crommie D. To redeem them from death. Reactions of family members to autopsy. Am J Med. 1986;80:665-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/