Published online Sep 20, 2024. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v14.i3.98525

Revised: July 15, 2024

Accepted: August 6, 2024

Published online: September 20, 2024

Processing time: 62 Days and 2.9 Hours

Anal carcinoma is a relatively rare tumor that accounts for approximately 2% of gastrointestinal malignancies and less than 7% of anorectal cancers. Most anal tumors originate between the anorectal junction and the anal verge. Risk factors for the disease include human papillomavirus infection, human immunodeficiency virus, tobacco use, immunosuppression, female sex, and older age. The pathogenesis of anal carcinoma is believed to be linked to human papillomavirus-related inflammation, leading to dysplasia and progression to cancer. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of anal tumor, with an annual incidence of approximately 1 to 2 per 100000 persons. Treatment regarding anal cancer has emerged over time. However, chemoradiation therapy remains the mainstay approach for early localized disease. Patients with metastatic disease are treated with systemic therapy, and salvage surgery is reserved for disease recurrence following chemoradiation. This article aims to provide background information on the epidemiology, risk factors, pathology, diagnosis, and current trends in the management of anal cancer. Future directions are briefly discussed.

Core Tip: Anal cancer is a rare malignancy, comprising 1%-6% of anorectal tumors. The incidence of anal carcinoma has been steadily increasing worldwide, and diagnosis is often challenging due to the similarities in clinical presentation to benign rectal diseases such as hemorrhoids. Roughly 85% of anal cancers are squamous cell carcinoma, and human papillomavirus infection and immunosuppression are major risk factors for the disease. Chemoradiation is the treatment of choice for early-stage cancer, while systemic therapy is used for metastatic disease. Novel cytotoxic agents in combination with immunotherapy have produced favorable outcomes in patients with advanced disease.

- Citation: English KJ. Anal carcinoma - exploring the epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Exp Med 2024; 14(3): 98525

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v14/i3/98525.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v14.i3.98525

Anal carcinoma is a rare disease entity that accounts for less than 5% of cancers of the intestine[1]. In the general population, the incidence of anal cancer has steadily increased from 1.2 in 1992 up to 1.9 per 100000 persons in the United States alone, according to data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program in 2024[2]. Among anal cancers, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the predominant histological subtype, followed by adenocarcinoma and rarer tumors such as basal cell carcinoma (BCC), melanoma, and small cell carcinoma[3,4].

Treatment of anal tumors has evolved over several decades, with concurrent mechanism identification. The primary choice of management has undergone a radical shift from abdominoperineal resection (APR) to organ-preserving chemoradiation therapy (CRT) and surgery[5]. Furthermore, recent developments using immunotherapy for advanced disease and metastasectomy in selected cases highlight the continuous changes and evolution of disease management[6,7]. In this article, we provide a scoping review of anal carcinoma and its epidemiology, risk factors, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management.

Anal cancer is an uncommon tumor that comprises less than 2% of large bowel malignancies and approximately 1%-6% of anorectal tumors[1,3,4]. This cancer has become more prevalent in Western nations such as Australia and the United States, with little to no change in Asian countries and Spain[8]. In the United States, between the period of 1994 to 2000, the incidence of anal cancer almost doubled, with a rate of 2.04 per 100000 in males and 2.06 per 100000 in females, in comparison with the period between 1973 and 1979, where the incidence was 1.06 per 100000 in males and 1.39 per 100000 in females[2,5]. Incidence rates in the United Kingdom and across Europe range from 0.7 to 1.7 per 100000 persons per year[9,10].

In 2020, the global anal cancer incidence was estimated at 0.65 per 100000 persons, with 50865 cases[11]. The world

The development of anal cancer is linked to multiple risk factors. Social and cultural dynamics over the last few decades have played a significant role in patient exposure and increased rates of anal tumors. The most notable risk factors are as follows.

HPVs are a group of double-stranded circular DNA oncovirus from the Papillomavirdae family, commonly transmitted by mucosa-mucosa or skin-to-skin contact and entering the body by mucosal or cutaneous trauma in the form of oral sex, vaginal, or anal intercourse[14]. The infection is the most common sexually transmitted disease worldwide, with prevalence variation regionally[15]. The lifetime risk of infection at least once among men and women is 50%, and HPV serves as the underlying cause of cervical cancer[14,16,17]. In fact, female patients with cervical cancers are at increased risk for anal cancer[18].

Anal malignancies are often associated with HPV infection, although it is relatively uncommon for most patients with this infection to acquire anal cancer[12,19]. Anal carcinoma is commonly linked to HPV infection, most notably subtype 16[20]. Another high-risk subtype, HPV-18, is found in some anal tumors, but is less common than HPV-16[19,21]. Subtypes 6 and 11 are less likely to become malignant and are commonly found in anogenital warts[22]. Other subtypes, including HPV-31, 33, and 45, have been implicated in a small number of anal cancer cases and have been linked to vulvar, cervical, and vaginal cancers in females, and penile cancer in males[20,23,24]. Verruca vulgaris (common warts) are often associated with the low-risk subtypes (1, 2, 4, and 7), with occasional high-risk subtypes (16 and 18) as a cause[25]. Anal SCC is the most common histopathological subtype, and HPV is implicated in more than 80% of tumor samples[26].

Male circumcision is associated with lower rates of HPV infection and transmission[27,28]. A meta-analysis across 32 studies that analyzed the relationship between male circumcision and HPV infection rates found decreased odds of prevalence of HPV infections [odds ratio = 0.45; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.34-0.61], reduced incidence rate of HPV infection (incidence rate ratio = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.57-0.83), and increased risk of clearing HPV infections (risk ratio = 1.44; 95%CI: 1.28-1.61) at the glans penis in male subjects[29]. The HPV vaccine and condoms are also implicated in protecting and reducing virus transmission rates[30,31]. However, condoms do not offer complete protection because they do not mask all areas of the body that may be susceptible to infection, such as the anus[30,31].

Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are considered high risk for anal cancer[32]. Incidence rates of anal carcinoma among HIV-infected individuals are 30 times higher compared to the general population[33]. A cohort study by Silverberg et al[34] that compared the incidence rates among 34189 HIV-infected [55% men who have sex with men (MSM), 19% other men, 26% women] and 114260 HIV-noninfected (90% men) individuals found the unadjusted incidence rate per 100000 person-years to be 131 for HIV-positive MSM, 46 for other HIV-infected men, and 2 for HIV-negative men. HIV-infected women had an anal carcinoma rate of 30 per 100000 person-years, with no cases observed for HIV-noninfected women[34]. The use of highly active retroviral therapy has not reduced the incidence of anal cancer, and a systematic review revealed a continued increase in the incidence of anal carcinoma among HIV-infected women, despite the use of highly active retroviral therapy[35,36].

Tobacco use is an independent risk factor for anal carcinoma[37]. It is associated with anal cancer disease recurrence and higher mortality rates[37,38]. A study conducted by Phillips et al[39], which measured smoking-related DNA adducts in the anal epithelium among smokers (n = 20) and age-matched life-long non-smokers (n = 16), showed high adduct levels among smokers compared to controls. The authors concluded that tobacco smoke inflicts genotoxic damage in the anal epithelium of smokers as a plausible mechanism for its association with anal cancer.

Compromised immune function is associated with increased risk for anal cancer[40]. According to a population-based cohort study conducted in Denmark by Sunesen et al[41], immunosuppression in the form of autoimmune diseases, solid organ transplantation, and hematologic malignancy are all strongly associated with the development of anal carcinoma.

MSM are 20 times more likely to be diagnosed with anal cancer than heterosexual men, with a rate of approximately 40 cases per 100000 people[42]. HIV-infected MSM are up to 40 times more likely to develop anal cancer, resulting in a rate of 80 cases per 100000 people[42,43]. The high incidence is related to significant HPV infection rates[43,44]. Modifiable behavioral factors such as condom and drug use can lower infection rates and cancer incidence[43].

Anal cancer has a predilection for females compared to males, most notably due to high HPV infection rates among the sex[45,46]. Several factors, including multiple sexual partners, sex at an early age, and having an uncircumcised sexual partner, all contribute to higher rates of HPV infection and, therefore, high rates of anal cancer compared to their male counterparts[45-47].

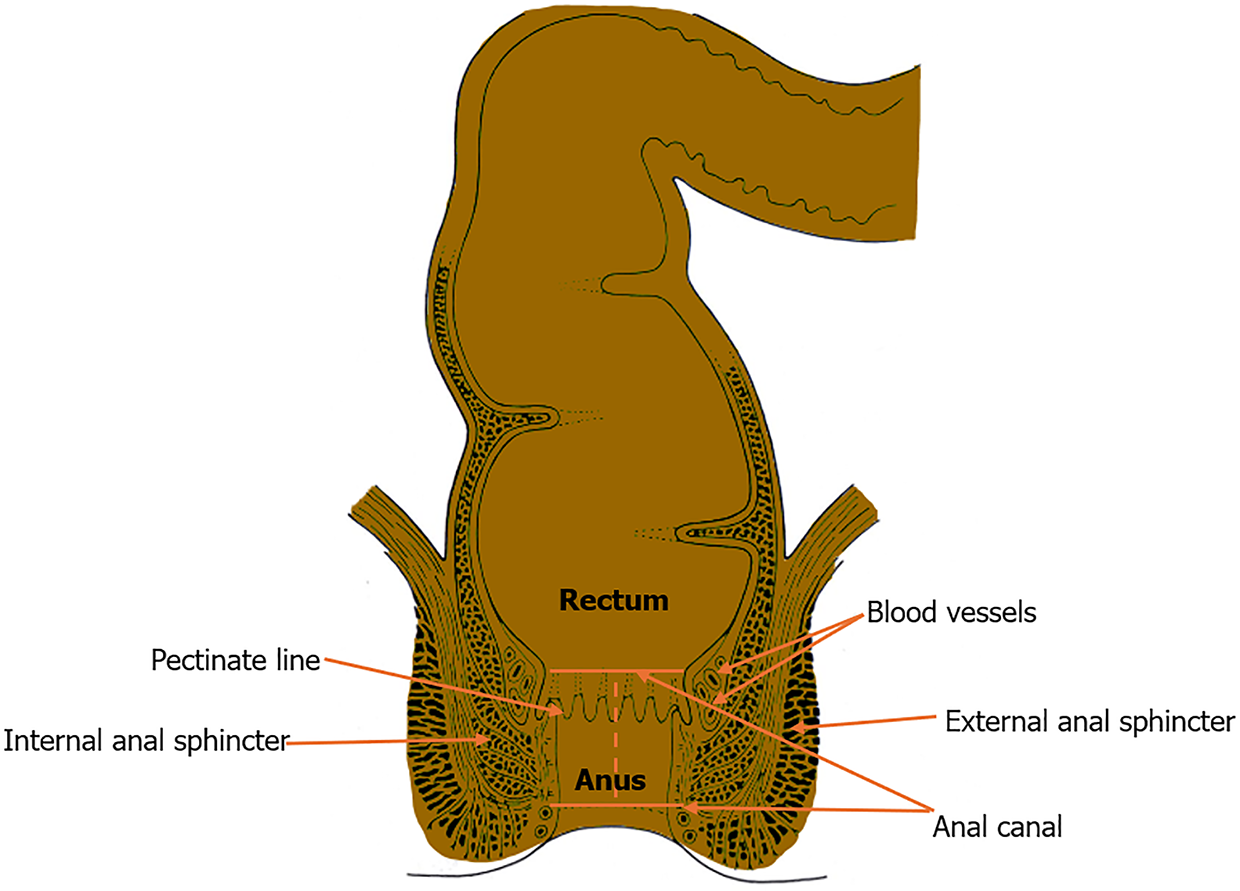

The anal canal (Figure 1) is the terminal portion of the alimentary tract that extends from the anorectal junction to the anal margin[51]. The upper portion of the canal derives from the dorsal section of the cloaca (endoderm), and the lower part is derived from the proctodeum (ectoderm)[51,52]. The canal measures approximately 4 cm and is continual with the rectum at the anorectal junction that forms an angle (anorectal angle) at the levator ani[51-53]. The muscular layer of the canal shapes the internal and external anal sphincters, and the tube contains longitudinal folds of mucosa that join inferiorly to make semicircular anal valves[53,54]. These valves form the pectinate (dentate) line, which demarcates the superior two-thirds of the anal canal from the inferior one-third[55]. The pectinate line is a watershed area that varies in neurovascular supply[55,56]. The epithelium above this line is columnar, while below is a transition zone lined by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium known as the anal pecten[57]. Further below, the anal pecten ends at the anocutaneous (white) line, where the epithelium resembles true skin (i.e. keratinized stratified squamous with sebaceous glands and hair)[57,58].

The anal canal above the pectinate line receives blood supply from the superior rectal artery (branch of the inferior mesenteric artery), median sacral arteries, and anastomosing branches from the middle rectal artery[55,56,59]. The venous drainage anastomoses with the rectal venous plexus and, above the line, drains from the superior rectal vein to the inferior mesenteric vein (portal venous system)[57-60]. Below the dentate line, the middle and inferior rectal veins drain to the internal pudendal vein, a tributary of the internal iliac vein[58-60]. Lymph drains primarily to the internal iliac nodes above the line, while inferiorly, it drains to the superficial inguinal nodes[60,61]. Above the pectinate line, the anal canal receives visceral innervation via the inferior hypogastric plexus[62]. As a result, the superior portion of the canal is susceptible to stretching[62,63]. Below the line, the canal receives somatic innervation through the inferior rectal branches of the pudendal nerves and, consequently, is sensitive to pain, temperature, and touch[63,64].

Integration of HPV double-stranded DNA into the host cell genome facilitates the expression of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7, promoting tumor oncogenesis of anal SCC[65]. These proteins express stimulatory properties, leading to a complex inflammatory progression to invasive cancer[65,66]. During integration, a destruction of a segment of the E2 domain of the viral genome occurs in the DNA of the infected cells, which leads to a loss of suppressor function of the E2 protein[65-67]. Due to this loss of activity, E6 and E7 proteins have increased expression with stimulatory properties, promoting invasion and keratinocyte immortalization[65-68].

HPV-related neoplasm requires E6 and E7 expressions to establish and maintain a transformed state[67,68]. Within this environment, the E7 complex interacts with the retinoblastoma protein, and E6 binds and inactivates tumor suppression protein p53[67-69]. This complex interplay serves as the primary mechanism for HPV-related anal SCC[65-69]. HIV-associated anal cancer is believed to be related to microsatellite instability, leading to the progression of invasive carcinoma[70].

Regarding immunohistochemistry (Table 1), SCC express cytokeratin (CK) 5/6, CK 13/19, pan CK antibody (AE1/AE3), and p63 protein[66-71]. The presence of the p63 protein on immunohistochemistry is highly specific for anal SCC[68-71]. Adenocarcinoma of the anal gland, in contrast, commonly expresses CK 7/20 (+/-)[67-71]. Adenoid cystic tumors are usually CK 7+, and melanocytic markers (i.e. S-100, human melanoma black-45, and Melan-A) are positive in melanomas[72,73]. Neuroendocrine tumors are positive for neuroendocrine markers (i.e. chromogranin A and serum neuron-specific enolase), and lymphoid cancers express lymphoid markers[74,75]. Perianal Paget disease commonly expresses CK 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15[76]. Paget disease with associated anorectal cancer is typically CK 20+[76].

| Tumor markers | Squamous cell carcinoma | Anal adenocarcinoma | Melanoma | Basal cell carcinoma | Neuroendocrine | Paget primary | Paget secondary |

| AE1/AE2 | + | + | - | + | + | + | + |

| Ber-EP4 | - | + | - | + | - | + | + |

| CAM5.2 | + | + | - | Nonspecific | + | + | + |

| CDX-2 | - | Mostly- | - | - | - | - | + |

| CEA | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| Chromogranin | - | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| CK5/6 | + | - | + | - | - | - | |

| CK7/20 | -/- | +/Mostly- | - | -/- | -/- | +/- | Mostly-/+ |

| GCDFP-15 | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| HMB45 | - | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| MELAN-A | - | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| Mucin | - | + | - | - | - | + | + |

| p63 | + | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| S100 | - | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| Synaptophysin | - | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| Vimentin | - | - | + | - | - | - | - |

Anal cancer commonly originates at the squamocolumnar junction and arises from precancerous lesions termed anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN)[77]. These lesions are frequently called squamous intraepithelial lesions, and are grouped according to their grade and degree of dysplasia[77,78]. AIN 2/3 are commonly classified as high-grade squamous intraepithelial neoplasia and are found in most patients with anal cancer[77,78]. Consequently, patients who are at increased risk for AIN 2/3, which includes MSM, solid organ transplant recipients, immunocompromised patients, and women with any history of vulvar, vaginal, and cervical cancer should undergo regular screening with anal cytology[77-79].

AIN has been found to be biologically similar to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) due to its common association with HPV, which is found in most cancers of the anus and cervix[80]. Current modes of treatment include topical medications, laser therapy, fulguration, and ablative techniques in the form of infrared coagulation, surgical excision, and thermal ablation. Topical treatment options include imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and trichloroacetic acid[81].

The World Health Organization has classified tumors of the anal canal into intraepithelial and invasive neoplasms that are further divided into epithelial and nonepithelial tumors (Table 2). The most notable ones are as follows.

| Tumor type | Characteristics |

| Epithelial tumors | |

| Premalignant lesions | Intraepithelial neoplasia (dysplasia), low-grade |

| Intraepithelial neoplasia (dysplasia), high-grade | |

| Bowden disease | |

| Perianal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia | |

| Paget disease | |

| Carcinoma | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Adenocarcinoma | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | |

| Small cell carcinoma | |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | |

| Others | |

| Nonepithelial tumors | Leiomyoma |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | |

| Myofibroma | |

| Carcinoid tumors | NA |

| Melanoma | NA |

| Secondary tumors | Direct extension from adjacent organs: Rectal, cervical, and prostate carcinoma |

Anal Paget disease commonly involves the perianal skin and is found in apocrine-rich areas[76,82]. Malignant cells produce mucus, and perianal spread is characterized by the proliferation of pagetoid cells within the epithelium[76,82,83]. Tumor cells on histological appearance often show large cells with giant nuclei and pale cytoplasm[82-84]. Pagetoid cells also occasionally acquire a signet ring appearance[82-85].

More than 80% of anal cancers are SCC[3,4]. These tumors arise primarily at the transformation zone between the columnar and squamous epithelium of the canal[3,4,33-36]. The cells that constitute these tumors have varying features, with some having giant pale eosinophilic characteristics and others having no areas of keratinization[86]. Other cells facilitate tumor nests (tumor-cell islands) that may appear with central keratinization and intercellular bridges or peripheral palisading on histology[86,87]. SCC tumors lack a myoepithelial layer within and around the basement membrane, and may resemble adnexal, skin, and salivary gland neoplasms[86,87].

Adenocarcinoma accounts for approximately 5% to 10% of cancers of the anal canal[4,88,89]. This histological tumor type primarily originates from the anal epithelium and includes primary adenocarcinomas that arise in the mucosa, anal glands, and fistula[89,90]. These tumors may also appear as small, ulcerated lesions near the anal duct, and possess some association with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s, and Paget’s disease[89-92]. Tumors are commonly mucin-positive and are treated similarly to rectal cancer[4,89-92].

BCC, the rarest type of anal cancer, accounts for less than 0.2% of anal neoplasms and predominantly affects the skin around the anal region[93,94]. It arises from perianal lesions and tends to remain local[93,94]. Anal BCC shares similar histological features with a known variant of SCC[94]. This variant, termed SCC with basaloid features, tends to show nests of oval cells with varying ratios of eosinophilic to basophilic cytoplasm, assorted mitotic activity, and peripheral nuclear palisading[94-96]. Perianal BCC has a better prognosis than SCC with basaloid features, and the nodular subtype is the predominant histologic type found in most cases[94-97].

Carcinoid tumors of the anal canal (rectal carcinoid) are rare and account for 1% to 1.3% of all anal cancers[98]. These tumors are commonly asymptomatic and are found incidentally on routine colonoscopy[98,99]. Rectal carcinoids are of neuroendocrine origin and are well differentiated[99]. Due to this fact, they are associated with a favorable prognosis, although they can metastasize[98,99]. This ability to spread is more likely with a tumor size greater than 10 mm and atypical features[99,100]. On histological appearance, these tumors show a trabecular growth pattern with nest- or rose-like structures[100,101]. Immunohistochemistry markers for neuroendocrine tumors include chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuro-specific enolase. However, the most sensitive marker for rectal carcinoids is SABT2, which is positive in more than 85% of rectal carcinoids[101,102].

Anal melanomas are rare and account for only 1% of all anorectal malignant tumors[103]. These are often acro-lentiginous and are usually found as pigmented ulcerated lesions[103,104]. Melanomas of the anal canal are typically aggressive and exhibit poor prognosis due to the lack of symptoms and late disease presentation[105]. The histological types of anal melanoma include lymphoma-like, spindle-cell, epithelioid, and pleomorphic[103-105]. The spindle-cell anal melanoma can be easily misdiagnosed as a gastrointestinal stromal tumor[105,106]. For this reason, analysis of immunohistochemistry is vital for the correct diagnosis[105]. Anal melanoma most commonly expresses S-100 on immunohistochemistry and c-Kit positive in over 70% of cases[103-106].

Most patients with anal cancer typically present with symptoms resembling benign diseases such as fissures and hemorrhoids[4,107]. Patients may complain of abdominal/rectal pain and bleeding on toilet paper after wiping[4,107]. In other cases, patients may be asymptomatic[4,107,108]. A complete history and physical examination are crucial to prognosis as patients with early diagnosis have better clinical outcomes[108-110]. Physicians should have a high index of clinical suspicion for patients presenting with symptoms resembling benign disease, and possess a low threshold for imaging studies and biopsy of suspected lesions[107-111]. Imaging modalities used in the diagnosis of anal cancer are as follows.

Three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound (3D-EAUS) is a valuable tool that allows a detailed evaluation of the anatomy and diseases of the anal canal[112]. It can accurately assess the depth of invasion of cancer into the anal sphincter complex and gauge tumor response to CRT[112,113]. 3D-EAUS is easy to perform and reproduce with high diagnostic accuracy[112-114]. A large study by Reginelli et al[114], which compared the diagnostic performance of 3D-EAUS and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the detection of anal cancer, found a detection rate of 100% using ultrasound compared to 93.1% for MRI.

Computed tomography (CT) scan is a valuable tool in the diagnosis of anal cancer[115]. Contrast-enhanced CT scan may visualize an anal tumor as a hypo-attenuated necrotic mass[5,115]. CT scan is also helpful in evaluating lymph node metastases and distant metastatic disease[115,116]. Although useful in the diagnostic work-up of anal cancer, recent guidelines have geared toward better imaging modalities such as MRI, positron emission tomography (PET), and PET/CT scan[115-117]. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Mahmud et al[117] comparing PET/CT or PET with standard imaging studies showed a 67% sensitivity to detect primary tumors with CT scan alone compared to 99% for PET or PET/CT scan.

Phased-array MRI is a useful tool for the diagnosis and staging of anal cancer[118]. In 2014, the European Society of Medical Oncology guidelines proposed that pelvic MRI should be mandatory in the diagnostic work-up of anal cancer, citing superior soft-tissue resolution compared to conventional (standard) imaging modalities (i.e. 3D-EAUS and CT scan)[119]. MRI detects neoplastic nodes, the extent of tumor infiltration into nearby organs, and the circumferential tumor extent[119,120]. It is greater than 90% sensitive in identifying anal carcinoma, and provides specific detail regarding the position of the tumor[120].

PET/CT scan with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET/CT) is an accurate and effective imaging modality for the detection and staging of anal cancer[121]. PET detects tumors based on molecular alterations and plays a vital role in post-treatment restaging of anal cancer patients[121,122]. FDG-PET/CT provides details regarding crucial markers for staging, such as the size of the tumor, the lymph nodes involved, and the detection of metastasis[121-123]. Of note, FDG-PET/CT is particularly sensitive for localized tumors less than 2 cm compared to standard imaging modalities[5,121-123].

The tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) classification system (Table 3) published by the American Joint Committee on Cancer is used to stage anal cancer[124]. This system is based on three essential factors.

| Primary tumor | Characteristics |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | HSIL (previously termed carcinoma in situ, Bowden disease, anal intraepithelial neoplasia II-III, high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia) |

| T1 | Tumor ≤ 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2 | Tumor > 2 cm but ≤ 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| T3 | Tumor > 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| T4 | Tumor of any size invades adjacent organ(s) (e.g., vagina, urethra, bladder) |

| Lymph nodes | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in inguinal, mesorectal, internal iliac, or external iliac nodes |

| N1a: Metastasis in inguinal, mesorectal, or internal iliac lymph nodes | |

| N1b: Metastasis in external iliac lymph nodes | |

| N1c: Metastasis in external iliac with any N1a nodes | |

| Metastasis | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

Tumor (T) describes the extent of the primary tumor and its size in relation to growth into nearby structures or organs[124,125]. A larger value after the T reflects a bigger tumor size and growth into nearby structures[125]. TX indicates that the primary tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information, and T0 means there is no evidence of a primary tumor[120,125]. T1 indicates tumor sizes less than 2 cm in the greatest dimension, T2 reflects tumor size between 2 and 5 cm, and T3 indicates tumor sizes more than 5 cm[124]. Lastly, T4 represents a tumor of any size that invades adjacent organs[120,124,125].

Lymph node (N) describes the spread of cancer to nearby lymph nodes[120,124]. NX indicates that regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to insufficient information[120,124]. N0 means no regional lymph node metastasis, and N1 indicates metastasis to nearby lymph nodes, such as the internal or external iliac nodes[120,124,125].

Metastasis (M) describes the spread of cancer to distant lymph nodes or organs[124]. M1 represents distant metastasis[120,124]. Anal cancer is staged based on TNM status (Table 4)[124]. Stage I and II are localized diseases[120,124]. Stage III indicates locally advanced cancer and stage IV represents metastatic disease[120,124,125].

| Stage | T | N | M |

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| IIA | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| IIB | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIA | T1-T2 | N1 | M0 |

| IIIB | T4 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIC | T3-T4 | N1 | M0 |

| IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Anal SCC was predominantly treated with radical resection before the 1970s[121-125]. This procedure involved the removal of the distal colon, rectum, anus, and anal sphincter complex through perineal and anterior abdominal wall techniques, which formed a permanent colostomy[126]. This procedure resulted in 5-year overall survival (OS) rates between 40% and 70% and a surgical mortality rate of 3%[127].

A shift in the approach to the treatment of anal SCC came when researchers at Wayne State University in 1974 investigated a therapeutic regimen for SCC consisting of chemotherapy and radiation[128]. This protocol (the Nigro regimen) consisted of 5-FU, fluoropyrimidine, and mitomycin-C (MMC) with a concurrent dose of gray[128]. The results were promising, as the first three patients treated with the regimen experienced complete tumor regression[128-130]. A subsequent follow-up study was conducted in which patients treated with the protocol only underwent a salvage APR if there was clinical evidence of disease residue[130]. The 5-year OS rate was 67%, and the 5-year colostomy-free survival rate was 59%. A total of 84% of patients in the follow-up study showed complete response to CRT.

These results sparked further investigation into the role of CRT in the management of anal cancer, and several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have since been done to cement CRT as the definitive treatment for anal cancer[131-135]. These trials have investigated the benefits of CRT vs radiotherapy (RT) alone, sequencing, and optimal chemothe

The United Kingdom Coordination Committee on Cancer Research phase 3 RCT, which involved 585 patients with anal SCC, compared RT to CRT[136]. The trial concluded that the use of 5-FU and MMC in combination with RT resulted in a 46% risk reduction in the local failure rate [relative risk (RR) = 0.54, 95%CI: 0.42-0.69], with a local failure rate of 36% with CRT vs 59% with RT. CRT was also associated with a significant reduction in cancer mortality, citing a 3-year anal cancer mortality of 39% with RT compared to 28% with CRT (RR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.53-0.95). A RCT by the European Organization for Research and Treatment compared the use of RT or CRT (5-FU and MMC) in patients with anal cancer[135]. CRT was found to be associated with more improvement in local and regional control rates. A 32% difference in colostomy-free time was observed between the two groups, and an 18% difference in local and regional failure rates.

MMC, although associated with toxicity, is an essential drug in chemotherapy regimens[137]. A phase 3 intergroup RCT that compared combined 5-FU and MMC to 5-FU alone showed a favorable colostomy-free rate (71% vs 59%, P = 0.014) and disease-free survival (DFS) (73% vs 51%, P = 0.0003) with combination chemotherapy at 4 years[134]. The addition of MMC to 5-FU, however, was associated with a greater risk of high-grade toxicity (23% vs 7%, P ≤ 0.001). Two RCTs then compared MMC to combined cisplatin and 5-FU, which revealed conflicting results[132,133]. The United States gastrointestinal (GI) intergroup radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) 98-11 phase 3 trial randomized anal cancer patients to CRT including 5-FU and MMC vs two induction cycles of 5-FU and cisplatin followed by CRT including 5-FU and cisplatin[133]. The 5-FU and MMC combinations were associated with better 5-year DFS and OS than the 5-FU and cisplatin combinations. DFS was 68% for 5-FU and MMC compared to 58% for 5-FU and cisplatin at 5 years; OS was 78% and 71%, respectively. The overall severity of toxicity was similar between the treatment arms. The results of RTOG 98-11 continued to support the use of combined MMC and 5-FU with RT for patients with anal SCC.

A 2 × 2 factorial trial, ACT II, conducted by the United Kingdom Coordination Committee on Cancer Research, also investigated the substitution of MMC with cisplatin[132]. Patients with anal cancer were first randomized to receive CRT with either MMC or cisplatin, followed by randomization to receive adjuvant therapy with 5-FU and cisplatin or observation. Both arms had similar complete response rates at approximately 90%. Toxicity rates were about 70%, with comparable OS and DFS. The progression-free survival was 74% for maintenance chemotherapy vs 73% for no maintenance at 3 years. The results of the ACT II and RTOG 98-11 trials have together solidified 5-FU and MMC as the standard of care for managing locoregional anal SCC[132,133]. Several studies have been published recently, which highlight that capecitabine and MMC appear to have equal efficacy to infusional 5-FU and MMC in the treatment of locally advanced anal SCC[138-140].

Intensity modulated RT (IMRT) is the preferred method for RT in the treatment of locoregional anal SCC[141]. This modality utilized variations in radiation intensities that facilitate more precise mapping of tumor targets and spares nearby structures[141,142]. The goals of treatment are to optimize radiation dose and duration to limit toxicity and locoregional recurrence[141,143]. IMRT is preferred over conventional RT based on the results of a phase two multicenter prospective RCT (RTOG 0529) that compared 3D-conformal RT to dose-painted IMRT[144]. The primary endpoint was a decrease in the combined rate of grade 2 + GI and genitourinary adverse events by at least 15% compared to previous results in the RTOG 98-11 trial[133,144]. Significant reductions in grade 2 hematologic, grade 3 dermatologic, and GI toxicity were observed in the IMRT group. However, despite the improved toxicity profile, retrospective studies have failed to show a difference in survival outcomes between cancer patients who received standard RT vs IMRT[145,146].

In locoregional anal cancer, CRT should be exhausted as the number one option for treatment due to better outcomes historically vs surgery[147,148]. APR and the formation of end colostomy should be reserved for salvage therapy in patients with tumor progression, disease recurrence following CRT, or patients who are ineligible for definitive CRT[148,149]. The exception to CRT as a first-line treatment for locoregional cancer is early-stage (stage I disease) perianal disease excluding the anal sphincter and superficially invasive anal SCC, for which a wide local excision is a treatment option[126,141].

Recurrent disease is defined as tumor discovery after 6 months post-CRT and a residual tumor if present within 6 months of treatment[150,151]. The average time for tumor recurrence of anal cancer is less than 12 months after CRT, and suspicion should prompt a detailed work-up with imaging and biopsy of all lesions to exclude metastasis[150]. The goal of management is to attain negative tumor margins, and patients are treated with APR with a permanent end colostomy and the creation of a sizable pelvic floor defect[151,152]. Salvage APR results in the control of disease locally in approximately 60% of all cases[151-153]. Salvage surgery also has a 5-year OS rate between 30 and 60%[154,155]. RT or brachytherapy following CRT has limited use in the management of local disease recurrence[141,156]. Similarly, the use of immunotherapy or systemic chemotherapy has limited data, and further research needs to be done to support use, although some articles have justified the use of MMC in the definitive management of local disease recurrence despite higher toxicity levels[141,157,158].

Systemic therapy is the current standard of treatment for patients with metastatic cancer or metastatic disease recurrence[159]. More than 10% of patients commonly experience distant relapse following CRT, and less than 10% of patients with de novo metastatic disease[159,160]. This first-line therapy is a platinum-based doublet regimen with either cisplatin or carboplatin and 5-FU or paclitaxel[161,162]. The phase 2 InterAACT trial randomized cancer patients with advanced anal SCC to treatment with either carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel or infusional 5-FU and cisplatin. Results suggested improvements in OS (20 months vs 12 months, P = 0.01) with the carboplatin/paclitaxel regimen and a favorable toxicity profile (36% vs 62% adverse event rate, P = 0.02) in comparison to the cisplatin and 5-FU regimen[163]. This trial established carboplatin/paclitaxel as the primary therapy for patients with metastatic disease and disease recurrence, and remains the standard of treatment for patients in the United States. Other studies have been done on regimens such as docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-FU (DCF) and 5-FU, leucovorin, and cisplatin (FOLFCIS)[164,165]. These studies have shown promising results, making DCF and FOLFCIS good alternative options for patients with metastatic disease.

According to guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, patients should be re-evaluated with a digital rectal examination and anoscopy 8 weeks to 12 weeks after completion of CRT[166]. Following evaluation, patients should be classified according to whether they have complete remission of the disease, persistent disease, or progressive disease.

Patients with complete remission should have digital rectal examinations and lymph node exams every 3 months to 6 months for 5 years after treatment. Anoscopy is also recommended every 6 months to 12 months for 3 years post-treatment. Imaging is suggested for stage II and III anal cancers in complete remission every year for 3 years and takes the form of a CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast or a CT of the chest without contrast, plus an MRI of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast.

Patients who are found to have remaining cancer that has not grown, or spread are classified as having persistent disease. Watchful waiting for a maximum of 6 months can be considered, as some anal cancers take longer to respond to treatment. Following this period, the patient should be reassessed, and then be categorized as progressive disease if there is persistent cancer or worsening following this period. If the cancer goes into remission, surveillance follows the complete remission protocol.

Lastly, if a follow-up examination 8 weeks to 12 weeks after CRT finds that the cancer has grown or spread, the patient should be classified as having progressive disease, and a biopsy should be performed. If biopsy results confirm progression, imaging (CT scan with contrast or non-contrast CT and MRI) should be done to assess the location and spread of the disease, and to determine treatment.

Anal cancer is a rare disease that accounts for approximately 0.5% of all new cancers in the United States and less than 3% of cancers of the intestine[4,167,168]. While the incidence of anal cancer is too low for general population screening, there is a specific subset of groups with increased risk for AIN 2/3, including HIV-positive patients, MSM, solid organ transplant recipients, women with any history of cervical, vulvar, or vaginal cancer, and immunocompromised patients not due to HIV[167-169]. The high burden of anal cancer in these populations is partly attributed to the higher prevalence of HPV infection[169,170]. As a result, these patients should be regularly screened with anal cytology (also termed anal pap testing, using a Dacron swab inserted into the anal canal)[171,172]. Patients with an abnormal pap test should then undergo frequent surveillance with high-resolution anoscopy[173,174].

A single-center prospective study that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of early anal cancer detection in high-risk patients (AIN-2+) using combined anal pap testing and high-resolution anoscopy showed that the diagnostic accuracy of anal cancer improves when the two tests are combined in comparison to anal pap testing alone[175].

HPV vaccination is a proven and cost-effective approach to the prevention of anal cancer in the younger population[176-178]. The administering of the 9-valent HPV vaccine to children could effectively prevent almost all anal tumors (primary prevention of anal SCC)[177]. Furthermore, the vaccine may help prevent AIN 2/3 and possible progression to SCC in high-risk groups[176-178]. This is true for populations that include MSM, HIV-positive men and women, solid organ transplant recipients, and women with a history of cervical cancer or CIN 3[177,179].

Although significant progress has been made with respect to the diagnosis and management of anal cancer, knowledge gaps still exist. More research is needed to address the prevention of anal carcinoma, especially in patients who are deemed high risk. Additionally, research focusing on minimizing the adverse effects of CRT in patients with early disease is crucial to improving the quality of life and survivorship care. Immunotherapy is an active area of research in the treatment of anal SCC. Therapeutic agents targeting programmed cell death receptor 1 have been shown to be effective against other HPV-related cancers, such as cutaneous SCC of the skin[6,180]. Due to this fact, several clinical trials are currently ongoing to investigate the efficacy of anti-programmed cell death receptor 1 agents in both metastatic and localized anal cancer (Table 5). Investigators are also currently assessing the role of monoclonal antibodies for use in anal cancer after the success of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (anti-EGFR) therapies for cancers of the head and neck[181-183]. Cetuximab, an EGFR inhibitor combined with an interleukin-15 receptor superagonist, is currently being studied in the treatment of advanced SCC[184].

| NCT number | Official title | Interventions | Study type | Phase | Status | Location |

| NCT04719988 | Ezabenlimab (BI 754091) and mDCF (Docetaxel, Cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil) Followed by Chemoradiotherapy in Patients With Stage III Squamous Cell Anal Carcinoma. A Phase II Study | Biological: Blood sample collection | Interventional | Phase 2 | Active | France |

| Procedure: Biopsy | ||||||

| NCT04894370 | Spartalizumab, mDCF (Docetaxel, Cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil) and Radiotherapy in Patients With Metastatic Squamous Cell Anal Carcinoma. A Phase IIA Study | Biological: Sample collection | Interventional | Phase 2 | Recruiting | France |

| NCT04708470 | A Phase I/II Study of Combination Immunotherapy for Advanced Cancers Including HPV-Associated Malignancies, Small Bowel, and Colon Cancers | Drug: Bintrafusp Alfa | Interventional | Phases 1 and 2 | Recruiting | United States |

| Drug: NHS-IL12 | ||||||

| Drug: Entinostat | ||||||

| NCT04432597 | Phase I/II Trial of HPV Vaccine PRGN-2009 Alone or in Combination With Anti-PD-L1/TGF-Beta Trap (M7824) in Subjects With HPV-Positive Cancers | Biological: PRGN-2009 (Phase I) | Interventional | Phases 1 and 2 | Active | United States |

| Biological: PRGN-2009 (Phase II) | ||||||

| Biological: M7824 | ||||||

| Diagnostic test: MRI | ||||||

| Diagnostic test: Bone scan | ||||||

| Diagnostic test: CT scan | ||||||

| Diagnostic test: Brain CT | ||||||

| Diagnostic test: Brain MRI | ||||||

| Procedure: Biopsy (Phase I) | ||||||

| Procedure: Biopsy (Phase II) | ||||||

| NCT05544929 | A Phase I, Open-label, Multicenter Study of KFA115 as a Single Agent and in Combination With Pembrolizumab in Patients With Select Advanced Cancers | Drug: KFA115 | Interventional | Phase 1 | Recruiting | United States |

| Drug: Pembrolizumab | ||||||

| NCT04357873 | Phase II Basket Trial Evaluating the Efficacy of a Combination of Pembrolizumab and Vorinostat in Patients With Recurrent and/or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Drug: Pembrolizumab; vorinostat | Interventional | Phase 2 | Active | France |

| NCT04802876 | Efficacy of Tislelizumab and Spartalizumab Across Multiple Cancer-types in Patients With PD1-high mRNA Expressing Tumors Defined by a Single and Pre-specified Cutoff | Drug: Spartalizumab | Interventional | Phase 2 | Recruiting | Spain |

| Drug: Tislelizumab |

Additional novel therapies, including triplet immunotherapy and HPV-targeted vaccines, are presently being studied in clinical trials. Pembrolizumab, in combination with a bifunctional EGFR/transforming growth factor β fusion protein, is actively being investigated in the phase I KEYNOTE-E28 clinical trial in patients with recurrent or metastatic SCC[185]. UCPVax, derived from telomerase, is a CD4 helper T-inducer vaccine currently being studied in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors for HPV-positive malignancies, including SCC, in the VolATIL trial[186]. Lastly, circulating tumor DNA is an emerging tool being investigated in the current NOAC9 phase 2 clinical trial[187]. This trial compares standard surveillance vs HPV-positive circulating tumor DNA-guided image follow-up to assess for improved detection of early treatment failure or recurrence.

Although anal cancer is rare in the general population, its incidence has been steadily increasing over the past decade. SCC is the predominant subtype of anal cancer and is HPV-mediated in most cases. The overall management of anal cancer has evolved over the past few decades. Currently, CRT, with the use of 5-FU and MMC, is the standard treatment for patients with early and locoregional disease. Wide local excision is a treatment option for a small subset of patients with stage I disease. Recurrence occurs in more than 20% of patients and requires salvage APR. A platinum-based doublet regimen is the mainstay of treatment for patients with metastatic disease. Immunotherapy is a treatment option for disease progression, and HPV vaccination is an effective long-term approach to limiting HPV-related anal cancer, especially in younger patients. Physical examination, in conjunction with routine screening, may increase detection of anal cancer in high-risk patients, which ultimately may reduce patient morbidity and mortality.

| 1. | Young AN, Jacob E, Willauer P, Smucker L, Monzon R, Oceguera L. Anal Cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100:629-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | National Cancer Institute. SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics [Internet] Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute; 2023 Apr 19. Data source(s): SEER Incidence Data, November 2022 Submission (1975-2020), SEER 22 registries. [cited 20 May 2024]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/. |

| 3. | Grulich AE, Poynten IM, Machalek DA, Jin F, Templeton DJ, Hillman RJ. The epidemiology of anal cancer. Sex Health. 2012;9:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Morton M, Melnitchouk N, Bleday R. Squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018;42:486-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Salati SA, Al Kadi A. Anal cancer - a review. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2012;6:206-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dhawan N, Afzal MZ, Amin M. Immunotherapy in Anal Cancer. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:4538-4550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ciardiello D, Guerrera LP, Maiorano BA, Parente P, Latiano TP, Di Maio M, Ciardiello F, Troiani T, Martinelli E, Maiello E. Immunotherapy in advanced anal cancer: Is the beginning of a new era? Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;105:102373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Islami F, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bray F, Jemal A. International trends in anal cancer incidence rates. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:924-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wilkinson JR, Morris EJ, Downing A, Finan PJ, Aravani A, Thomas JD, Sebag-Montefiore D. The rising incidence of anal cancer in England 1990-2010: a population-based study. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:O234-O239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mignozzi S, Santucci C, Malvezzi M, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Global trends in anal cancer incidence and mortality. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2024;33:77-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Huang J, Lok V, Zhang L, Lucero-prisno DE, Xu W, Zheng Z, Elcarte E, Withers M, Wong M. IDDF2022-ABS-0273 Global incidence of anal cancer by histological subtypes. Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Silva Dalla Libera L, Almeida de Carvalho KP, Enocencio Porto Ramos J, Oliveira Cabral LA, de Cassia Goncalves de Alencar R, Villa LL, Alves RRF, Rabelo Santos SH, Aparecida Dos Santos Carneiro M, Saddi VA. Human Papillomavirus and Anal Cancer: Prevalence, Genotype Distribution, and Prognosis Aspects from Midwestern Region of Brazil. J Oncol. 2019;2019:6018269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mduma E, Dharsee N, Samwel K, Mwita CJ, Lidenge SJ. Clinicopathological Characteristics and Outcomes of Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients With and Without HIV Infection in Sub-Saharan Africa. JCO Glob Oncol. 2023;9:e2200394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brianti P, De Flammineis E, Mercuri SR. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol. 2017;40:80-85. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Plotzker RE, Vaidya A, Pokharel U, Stier EA. Sexually Transmitted Human Papillomavirus: Update in Epidemiology, Prevention, and Management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2023;37:289-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 16. | Choi S, Ismail A, Pappas-Gogos G, Boussios S. HPV and Cervical Cancer: A Review of Epidemiology and Screening Uptake in the UK. Pathogens. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chan CK, Aimagambetova G, Ukybassova T, Kongrtay K, Azizan A. Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, and Vaccination-Review of Current Perspectives. J Oncol. 2019;2019:3257939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sehnal B, Dusek L, Cibula D, Zima T, Halaska M, Driak D, Slama J. The relationship between the cervical and anal HPV infection in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Virol. 2014;59:18-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Gami B, Kubba F, Ziprin P. Human papilloma virus and squamous cell carcinoma of the anus. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2014;8:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lin C, Franceschi S, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus types from infection to cancer in the anus, according to sex and HIV status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:198-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Palmer JG, Scholefield JH, Coates PJ, Shepherd NA, Jass JR, Crawford LV, Northover JM. Anal cancer and human papillomaviruses. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:1016-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tyros G, Mastraftsi S, Gregoriou S, Nicolaidou E. Incidence of anogenital warts: epidemiological risk factors and real-life impact of human papillomavirus vaccination. Int J STD AIDS. 2021;32:4-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zaki SR, Judd R, Coffield LM, Greer P, Rolston F, Evatt BL. Human papillomavirus infection and anal carcinoma. Retrospective analysis by in situ hybridization and the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:1345-1355. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Kidd LC, Chaing S, Chipollini J, Giuliano AR, Spiess PE, Sharma P. Relationship between human papillomavirus and penile cancer-implications for prevention and treatment. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6:791-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Muršić I, Včev A, Kotrulja L, Kuric I, Milavić T, Šustić N, Tolušić Levak M. Treatment of verruca vulgaris in traditional medicine. Acta Clin Croat. 2020;59:745-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Ramos-Cartagena JM, Deshmukh AA, Torres-Cintrón CR, Colón-López V, Ortiz AP. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus Incidence, Mortality, and Survival Among the General Population and Persons Living With HIV in Puerto Rico, 2000-2016. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:133-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Giuliano AR, Nyitray AG, Albero G. Male circumcision and HPV transmission to female partners. Lancet. 2011;377:183-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shapiro SB, Wissing MD, Khosrow-Khavar F, El-Zein M, Burchell AN, Tellier PP, Coutlée F, Franco EL. Male Circumcision and Genital Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection in Males and Their Female Sexual Partners: Findings From the HPV Infection and Transmission Among Couples Through Heterosexual Activity (HITCH) Cohort Study. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1184-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shapiro SB, Laurie C, El-Zein M, Franco EL. Association between male circumcision and human papillomavirus infection in males and females: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2023;29:968-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pierce Campbell CM, Lin HY, Fulp W, Papenfuss MR, Salmerón JJ, Quiterio MM, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa LL, Giuliano AR. Consistent condom use reduces the genital human papillomavirus burden among high-risk men: the HPV infection in men study. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:373-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ellingson MK, Sheikha H, Nyhan K, Oliveira CR, Niccolai LM. Human papillomavirus vaccine effectiveness by age at vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19:2239085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Arnold JD, Byrne ME, Monroe AK, Abbott SE; District of Columbia Cohort Executive Committee. The Risk of Anal Carcinoma After Anogenital Warts in Adults Living With HIV. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:283-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shiels MS, Cole SR, Kirk GD, Poole C. A meta-analysis of the incidence of non-AIDS cancers in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:611-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Justice AC, Engels E, Gill MJ, Goedert JJ, Kirk GD, D'Souza G, Bosch RJ, Brooks JT, Napravnik S, Hessol NA, Jacobson LP, Kitahata MM, Klein MB, Moore RD, Rodriguez B, Rourke SB, Saag MS, Sterling TR, Gebo KA, Press N, Martin JN, Dubrow R; North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) of IeDEA. Risk of anal cancer in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals in North America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1026-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Duncan KC, Chan KJ, Chiu CG, Montaner JS, Coldman AJ, Cescon A, Au-Yeung CG, Wiseman SM, Hogg RS, Press NM. HAART slows progression to anal cancer in HIV-infected MSM. AIDS. 2015;29:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Piketty C, Selinger-Leneman H, Grabar S, Duvivier C, Bonmarchand M, Abramowitz L, Costagliola D, Mary-Krause M; FHDH-ANRS CO 4. Marked increase in the incidence of invasive anal cancer among HIV-infected patients despite treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2008;22:1203-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | McMahon KR, Gemma N, Clapp M, Sanchez-Montejo P, Dibello J, Laipply E. Relationship between anal cancer recurrence and cigarette smoking. World J Clin Oncol. 2023;14:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ramamoorthy S, Luo L, Luo E, Carethers JM. Tobacco smoking and risk of recurrence for squamous cell cancer of the anus. Cancer Detect Prev. 2008;32:116-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Phillips DH, Hewer A, Scholefield JH, Skinner P. Smoking-related DNA adducts in anal epithelium. Mutat Res. 2004;560:167-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bingmer K, Ofshteyn A, Dietz DW, Stein SL, Steinhagen E. Outcomes in immunosuppressed anal cancer patients. Am J Surg. 2020;219:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sunesen KG, Nørgaard M, Thorlacius-Ussing O, Laurberg S. Immunosuppressive disorders and risk of anal squamous cell carcinoma: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark, 1978-2005. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:675-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zhang Z, Ling X, Liu L, Xi M, Zhang G, Dai J. Natural History of Anal Papillomavirus Infection in HIV-Negative Men Who Have Sex With Men Based on a Markov Model: A 5-Year Prospective Cohort Study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:891991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Khandwala P, Singhal S, Desai D, Parsi M, Potdar R. HIV-Associated Anal Cancer. Cureus. 2021;13:e14834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Hoots BE, Palefsky JM, Pimenta JM, Smith JS. Human papillomavirus type distribution in anal cancer and anal intraepithelial lesions. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2375-2383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, Markowitz LE. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:813-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1040] [Cited by in RCA: 1017] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wang L, Yu C, Ni X, Wang F, Wen C, Jin M, Chen J, Zhang K, Wang J. Prevalence characteristics of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection among women receiving physical examinations in the Shangcheng District, Hangzhou city, China. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chelimo C, Wouldes TA, Cameron LD, Elwood JM. Risk factors for and prevention of human papillomaviruses (HPV), genital warts and cervical cancer. J Infect. 2013;66:207-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Liu Y, Bhardwaj S, Sigel K, Winters J, Terlizzi J, Gaisa MM. Anal cancer screening results from 18-to-34-year-old men who have sex with men living with HIV. Int J Cancer. 2024;154:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Dale JE, Sebjørnsen S, Leh S, Rösler C, Aaserud S, Møller B, Fluge Ø, Erichsen C, Nadipour S, Kørner H, Pfeffer F, Dahl O. Multimodal therapy is feasible in elderly anal cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:81-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Martinez-Cannon BA, Perez ACT, Hincapie-Echeverri J, Roy M, Marinho J, Buerba GA, Akagunduz B, Li D, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E. Anal cancer in older adults: A Young International Society of Geriatric Oncology review paper. J Geriatr Oncol. 2022;13:914-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Takahashi T, Ohta H, Azekura K, Ueno M. Coloanal anastomosis in surgery for rectal cancer. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2000;47:7-11. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Yamaguchi K, Kiyokawa J, Akita K. Developmental processes and ectodermal contribution to the anal canal in mice. Ann Anat. 2008;190:119-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Tsukada Y, Ito M, Watanabe K, Yamaguchi K, Kojima M, Hayashi R, Akita K, Saito N. Topographic Anatomy of the Anal Sphincter Complex and Levator Ani Muscle as It Relates to Intersphincteric Resection for Very Low Rectal Disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:426-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Lee JM, Kim NK. Essential Anatomy of the Anorectum for Colorectal Surgeons Focused on the Gross Anatomy and Histologic Findings. Ann Coloproctol. 2018;34:59-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Siddharth P, Ravo B. Colorectal neurovasculature and anal sphincter. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68:1185-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Guntz M, Parnaud E, Bernard A, Chome J, Regnier J, Toulemonde JL. [Vascularization of the anal canal]. Bull Assoc Anat (Nancy). 1976;60:527-538. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Tanaka E, Noguchi T, Nagai K, Akashi Y, Kawahara K, Shimada T. Morphology of the epithelium of the lower rectum and the anal canal in the adult human. Med Mol Morphol. 2012;45:72-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Fenger C. Histology of the anal canal. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:41-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Lund JN, Binch C, McGrath J, Sparrow RA, Scholefield JH. Topographical distribution of blood supply to the anal canal. Br J Surg. 1999;86:496-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Pandey P. Anal anatomy and normal histology. Sex Health. 2012;9:513-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Hardy KJ. The lymphatic drainage of the anal margin. Aust N Z J Surg. 1971;40:367-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Hieda K, Cho KH, Arakawa T, Fujimiya M, Murakami G, Matsubara A. Nerves in the intersphincteric space of the human anal canal with special reference to their continuation to the enteric nerve plexus of the rectum. Clin Anat. 2013;26:843-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Gagnard C, Godlewski G, Prat D, Lan O, Cousineau J, Maklouf Y. The nerve branches to the external anal sphincter: the macroscopic supply and microscopic structure. Surg Radiol Anat. 1986;8:115-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Kinugasa Y, Arakawa T, Murakami G, Fujimiya M, Sugihara K. Nerve supply to the internal anal sphincter differs from that to the distal rectum: an immunohistochemical study of cadavers. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:429-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Krzowska-Firych J, Lucas G, Lucas C, Lucas N, Pietrzyk Ł. An overview of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) as an etiological factor of the anal cancer. J Infect Public Health. 2019;12:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Soheili M, Keyvani H, Soheili M, Nasseri S. Human papilloma virus: A review study of epidemiology, carcinogenesis, diagnostic methods, and treatment of all HPV-related cancers. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2021;35:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Longworth MS, Laimins LA. Pathogenesis of human papillomaviruses in differentiating epithelia. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:362-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Hebner CM, Laimins LA. Human papillomaviruses: basic mechanisms of pathogenesis and oncogenicity. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16:83-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Ashique S, Hussain A, Fatima N, Altamimi MA. HPV pathogenesis, various types of vaccines, safety concern, prophylactic and therapeutic applications to control cervical cancer, and future perspective. Virusdisease. 2023;34:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Gervaz P, Calmy A, Durmishi Y, Allal AS, Morel P. Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus-an opportunistic cancer in HIV-positive male homosexuals. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2987-2991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 71. | van der Zee RP, Meijer CJLM, Cuming T, Kreuter A, van de Sandt MM, Quint WGV, de Vries HJC, Prins JM, Steenbergen RDM. Characterisation of anal intraepithelial neoplasia and anal cancer in HIV-positive men by immunohistochemical markers p16, Ki-67, HPV-E4 and DNA methylation markers. Int J Cancer. 2021;149:1833-1844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Weinstein D, Leininger J, Hamby C, Safai B. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in melanoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:13-24. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Lee SK, Kwon MS, Lee YS, Choi SH, Kim SY, Cho KJ, Nam SY. Prognostic value of expression of molecular markers in adenoid cystic cancer of the salivary glands compared with lymph node metastasis: a retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Eriksson B, Oberg K, Stridsberg M. Tumor markers in neuroendocrine tumors. Digestion. 2000;62 Suppl 1:33-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Morra E. The biological markers of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: their role in diagnosis, prognostic assessment and therapeutic strategy. Int J Biol Markers. 1999;14:149-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Chumbalkar V, Jennings TA, Ainechi S, Lee EC, Lee H. Extramammary Paget's Disease of Anal Canal Associated With Rectal Adenoma Without Invasive Carcinoma. Gastroenterology Res. 2016;9:99-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Roberts JR, Siekas LL, Kaz AM. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia: A review of diagnosis and management. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;9:50-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 78. | Brzeziński M, Stukan M. Anal Cancer and Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia Risk among Patients Treated for HPV-Related Gynecological Diseases-A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Albuquerque A. Cytology in Anal Cancer Screening: Practical Review for Clinicians. Acta Cytol. 2020;64:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Stanley MA, Winder DM, Sterling JC, Goon PK. HPV infection, anal intra-epithelial neoplasia (AIN) and anal cancer: current issues. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Siddharthan RV, Lanciault C, Tsikitis VL. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia: diagnosis, screening, and treatment. Ann Gastroenterol. 2019;32:257-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Thompson HM, Kim JK. Perianal Paget's Disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64:511-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Santos MD, Soares F, Presa-Fernandes JM, Silva DS. Perianal Paget Disease: Different Entities With the Same Name. Cureus. 2021;13:e15161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Perianal Paget's disease: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with and without associated rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:170-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Tang M, Gao X, Wang L, Liu W, Li J. A brief review of perianal paget disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2020;13:7241-7249. |

| 86. | Wietfeldt ED, Thiele J. Malignancies of the anal margin and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:127-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Sahai A, Kodner IJ. Premalignant neoplasms and squamous cell carcinoma of the anal margin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2006;19:88-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Taliadoros V, Rafique H, Rasheed S, Tekkis P, Kontovounisios C. Management and Outcomes in Anal Canal Adenocarcinomas-A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Tsay CJ, Pointer T, Chandler JB, Nagar AB, Protiva P. Anal adenocarcinoma: case report, literature review and comparative survival analysis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Lukovic J, Kim JJ, Krzyzanowska M, Chadi SA, Taniguchi CM, Hosni A. Anal Adenocarcinoma: A Rare Malignancy in Need of Multidisciplinary Management. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:635-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Lightner AL, Vaidya P, McMichael J, Click B, Regueiro M, Steele SR, Hull TL. Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Ulcerative Colitis: Can Pouches Withstand Traditional Treatment Protocols? Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64:1106-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Slater G, Greenstein A, Aufses AH Jr. Anal carcinoma in patients with Crohn's disease. Ann Surg. 1984;199:348-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Patil DT, Goldblum JR, Billings SD. Clinicopathological analysis of basal cell carcinoma of the anal region and its distinction from basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1382-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Alvarez-Cañas MC, Fernández FA, Rodilla IG, Val-Bernal JF. Perianal basal cell carcinoma: a comparative histologic, immunohistochemical, and flow cytometric study with basaloid carcinoma of the anus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Tsai TY, Liao CK, Zhang BY, Huang YL, Tsai WS, You JF, Yeh CY, Hsieh PS. Perianal Basal Cell Carcinoma-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Real-World Data. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Bulur I, Boyuk E, Saracoglu ZN, Arik D. Perianal Basal cell carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:25-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Pang LS, Morson BC. Basaloid carconoma of the anal canal. J Clin Pathol. 1967;20:128-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Peralta EA. Rare anorectal neoplasms: gastrointestinal stromal tumor, carcinoid, and lymphoma. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:107-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Jetmore AB, Ray JE, Gathright JB Jr, McMullen KM, Hicks TC, Timmcke AE. Rectal carcinoids: the most frequent carcinoid tumor. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:717-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Patterson S, Sogunro O. Rectal carcinoid in a 30-year-old male: a review of current treatment options. Dig Med Res. 2020;3:74-74. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 101. | Li Z, Yuan J, Wei L, Zhou L, Mei K, Yue J, Gao H, Zhang M, Jia L, Kang Q, Huang X, Cao D. SATB2 is a sensitive marker for lower gastrointestinal well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:7072-7082. [PubMed] |

| 102. | Bellizzi AM. SATB2 in neuroendocrine neoplasms: strong expression is restricted to well-differentiated tumours of lower gastrointestinal tract origin and is most frequent in Merkel cell carcinoma among poorly differentiated carcinomas. Histopathology. 2020;76:251-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Husain M, Rashid T, Ahmad MM, Hassan MJ. Anorectal malignant amelanotic melanoma: Report of a rare aggressive primary tumor. J Cancer Res Ther. 2022;18:249-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Charifa A, Zhang X. Morphologic and Immunohistochemical Characteristics of Anorectal Melanoma. Int J Surg Pathol. 2018;26:725-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Fastner S, Hieken TJ, McWilliams RR, Hyngstrom J. Anorectal melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2023;128:635-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Lagha A, Ayadi M, Krimi S, Chraiet N, Allani B, Rifi H, Raies H, Mezlini A. Primary anorectal melanoma: A case report with extended follow-up. Am J Case Rep. 2012;13:254-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Sauter M, Keilholz G, Kranzbühler H, Lombriser N, Prakash M, Vavricka SR, Misselwitz B. Presenting symptoms predict local staging of anal cancer: a retrospective analysis of 86 patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Pessia B, Romano L, Giuliani A, Lazzarin G, Carlei F, Schietroma M. Squamous cell anal cancer: Management and therapeutic options. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;55:36-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |