Published online Aug 20, 2015. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v5.i3.194

Peer-review started: March 23, 2015

First decision: April 10, 2015

Revised: April 22, 2015

Accepted: June 18, 2015

Article in press: June 19, 2015

Published online: August 20, 2015

Processing time: 155 Days and 17.1 Hours

AIM: To discuss treatment with eribulin in clinical practice outside a clinical trial.

METHODS: Archives of patients treated for metastatic breast cancer were reviewed and 21 patients treated with the new chemotherapeutic eribulin mesylate, a synthetic analog of a natural marine product, were identified. Information on patients’ characteristics and treatment outcomes was extracted. Treatment with eribulin mesylate was initiated at the recommended dose of 1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle in 17 patients and at a decreased dose of 1.1 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle in 4 patients due to comorbidities and frailty. Efficacy of the drug was evaluated using the revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria. Progression-Free Survival and overall survival (OS) were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method starting from the date of eribulin therapy initiation to the date of disease progression documentation or death, respectively.

RESULTS: The median age of patients at the time of eribulin mesylate treatment was 53 years (range 34-75). Sixteen patients had estrogen receptor (ER) and/or partial response (PR) positive disease and 5 had ER/PR negative disease (all triple negative). Eight patients had received 2 or 3 previous lines of chemotherapy for metastatic disease and 13 patients had received 4 or more lines of treatment. The median number of cycles of eribulin received was 3 (range 1-16 years). All patients, except one, discontinued treatment due to progressive disease and one patient due to adverse effects. Six patients had a dose reduction due to side effects. All patients had progressed at the time of the report with a median time to progression of 3 mo (range 1 to 14 mo). Fifteen patients had died with a median OS of 7 mo (range 1-18 mo). Six patients were alive with a median follow-up of 13.5 mo (range 7 to 19 mo).

CONCLUSION: This series of patients confirms the activity of eribulin in a heavily pre-treated metastatic breast cancer population consistent with phase II and III trials.

Core tip:This report discusses treatment with eribulin in clinical practice outside a clinical trial setting. It confirms the activity of eribulin in a heavily pre-treated metastatic breast cancer population.

- Citation: Digklia A, Voutsadakis IA. Eribulin for heavily pre-treated metastatic breast cancer patients. World J Exp Med 2015; 5(3): 194-199

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315X/full/v5/i3/194.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v5.i3.194

Breast cancer is the most common female carcinoma and among the most frequent causes of cancer mortality in women worldwide[1,2]. Metastatic breast cancer is considered incurable with an estimated median survival of 2 to 3 years and only 1 in 4 to 5 patients alive at 5 years after diagnosis. Treatment with endocrine, cytotoxic or targeted therapies has prolonged survival and may improve or maintain the quality of life of patients living with metastatic disease. Despite the availability of several active agents, there is a need to develop additional drugs in order to increase the treatment options in metastatic breast cancer patients.

Eribulin (previously known as E7389) is a new chemotherapy drug and has been approved by regulatory authorities for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer[3]. It is a microtubule inhibitor and a synthetic analog of the natural product halichondrin B isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria okadai. Its mechanism of action is unique among microtubule poisons and involves binding to polymerized tubulin without affecting de-polymerization and promoting tubulin sequestration in non-functional polymers[4]. It produces cell cycle arrest in the G2-M phase in vitro in several human cancer cell lines, including p-glycoprotein-expressing and paclitaxel-resistant lines, when incubated in the presence of nanomolar concentrations of the drug. Clinical development has led to the approval of eribulin for use as monotherapy in metastatic breast cancer patients who have received at least two prior chemotherapeutic regimens including an anthracycline and a taxane. This is consistent with the view that sequential monotherapies are preferable to combination therapies in most clinical scenarios in metastatic breast cancer as a means of preserving tolerability without compromising efficacy.

This report presents retrospective data on this drug in patients treated in two centers outside of a clinical trial.

Archives of all patients treated for metastatic breast cancer from 2011 to June 2014 were reviewed and 21 patients treated with eribulin were identified. Information on patients’ characteristics and treatment outcomes was extracted. Data on response, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were collected.

Treatment with eribulin mesylate was initiated at the recommended dose of 1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle in 17 patients and at a decreased dose of 1.1 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle in 4 patients due to comorbidities and frailty. Tumor response was reported according to the revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria[5]. Response rate was defined as the addition of complete response and partial response (PR). Disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the response rate plus the stable disease (SD) rate. PFS and OS are calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method starting from the date of eribulin therapy initiation to the date of disease progression documentation or death. Descriptive statistics parameters used in the study were performed with the aid of a non-commercial statistical calculation site (http://www.statpages.org).

Data collection and recording were conducted in compliance with the ethical requirements of our centers and patients’ anonymity was guaranteed. Given that the study was retrospective in nature and the fact that treatments had been provided according to standards of care, no specific informed consents were obtained from individual patients.

The median age of patients at the time of eribulin treatment was 53 years (range 34-75 years) (Table 1). The median age at the time of breast cancer diagnosis was 47 years (range 30-73 years). Nineteen patients were diagnosed initially with localized disease and had received adjuvant treatments and 2 patients had metastatic disease at diagnosis. Sixteen patients had Estrogen Receptor (ER) and/or Progesterone Receptor (PgR) positive disease and 5 had ER/PgR negative disease (all triple negative). Eight patients had received 2 or 3 previous lines of chemotherapy for metastatic disease and 13 patients had received 4 or more lines of treatment. The median number of previous lines of treatment was 4 (range 1-7). The median number of cycles of eribulin received was 3 (range 1-16). All patients had a heavy metastatic burden with two or more organs involved, including 5 patients with brain metastases and 10 patients with 4 or more metastatic organs.

| Median | Range | |

| Age at diagnosis | 47 | 30-73 |

| Age at eribulin treatment | 53 | 34-75 |

| Patients (n = 21) | % | |

| Hormonal status | ||

| ER/ PgR positive | 16 | 76.5 |

| ER/PgR / Her2 negative | 5 | 23.8 |

| Grade | ||

| III | 12 | 57.2 |

| II | 5 | 23.8 |

| Unknown | 4 | 19 |

| Performance status | ||

| 0-1 | 13 | 61.9 |

| 2-3 | 8 | 38.1 |

| Number of metastatic sites | ||

| 2 | 3 | 14.3 |

| More than 2 | 18 | 85.7 |

All patients, except one, discontinued treatment due to progressive disease and one patient due to adverse effects (grade 3 asthenia) (Table 2). Six patients had a dose reduction due to adverse effects including febrile neutropenia, asthenia and peripheral neuropathy. Other grade 2 or 3 adverse effects observed included anemia in 2 patients and thrombocytopenia and ileus in one patient each.

| Median | Range | |

| Progression-free survival (mo) | 3 | 1-14 |

| Overall survival (patients who died) | 7 | 1-18 |

| Follow-up (mo, patients alive) | 13.5 | 7-19 |

| Number of eribulin cycles | 3 | 1-16 |

| patients (n = 21) | % | |

| Previous lines of treatment | ||

| 3 or less | 8 | 38.1 |

| More than 3 | 13 | 61.9 |

| Reason for eribulin discontinuation | ||

| Progression | 20 | 95.2 |

| Adverse effects | 1 | 4.8 |

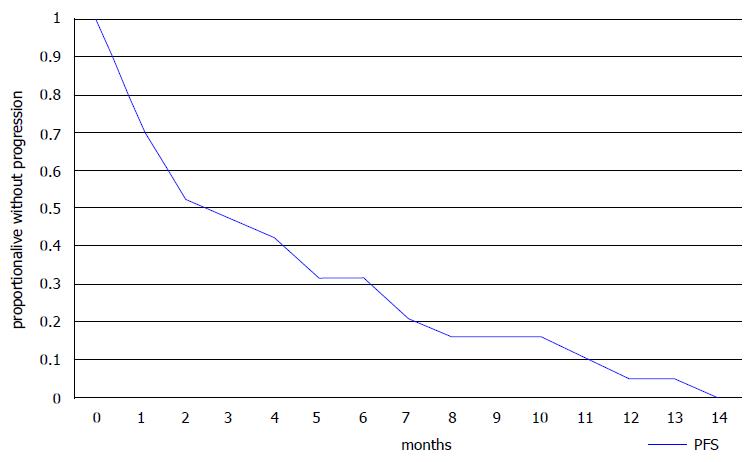

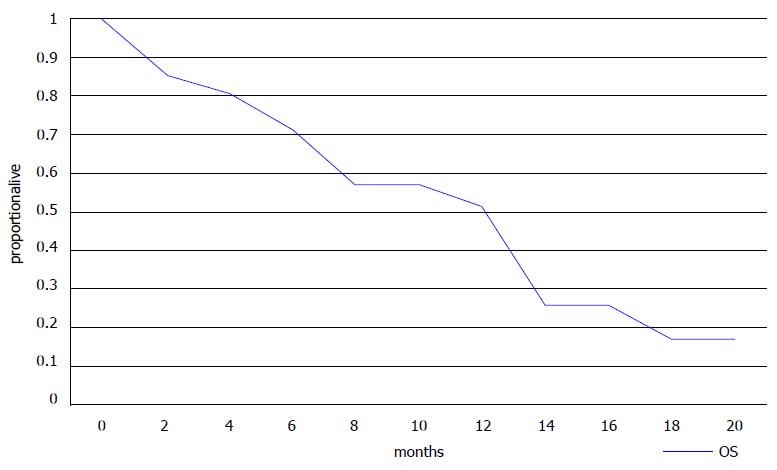

Ten of 18 evaluable patients had a PR or SD for more than 3 mo as their best response resulting in a DCR of 55.6% (Table 3). Six of eight patients with 3 or less lines of previous therapies had a PR or SD resulting in a DCR of 75%, but some of the more heavily pre-treated patients (4 of 10, 40%) also benefited from eribulin treatment (Table 3). Three patients died before an evaluation of the effect of therapy could be performed. All patients had progressed at the time of the report with a median time to progression of 3 mo (range 1 to 14 mo) (Table 2). Fifteen patients had died with a median OS of 7 mo (range 1-18 mo). Six patients were alive with a median follow-up of 16 mo (range 7 to 19 mo). Kaplan-Meier PFS and OS curves are presented in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

| All evaluable patients in the series (n = 18) | 95%CI | 3 or less previous lines of therapy (n = 8) | 95%CI | More than 3 previous lines of therapy (n = 10) | 95%CI | |

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PR | 7 (38.9) | 16.4-61.4 | 4 (50) | 18.7-81.8 | 3 (30) | 1.6-58.4 |

| SD | 3 (16.7) | 0-33.9 | 2 (25) | 0-55 | 1 (10) | 0-28.6 |

| PD | 8 (44.4) | 21.5-67.4 | 2 (25) | 0-55 | 6 (60) | 33.2-86.8 |

The new chemotherapeutic agent eribulin has shown activity in metastatic breast cancer and represents a new therapeutic option in this disease after failure of other therapies such as anthracyclines and taxanes[4].

Phase I studies have established the optimal three-weekly dose to be 1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 which has been carried out for further development[6]. Phase II and III studies have established the efficacy of eribulin in pre-treated metastatic breast cancer patients. Two phase III trials have compared eribulin to either physician’s choice or a capecitabine arm[7,8]. The first, the Eisai Metastatic Breast Cancer Study Assessing Physician's Choice versus E7389 open label, randomized, multicenter trial, included 762 patients who had received at least 2 previous lines of chemotherapy and were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to receive either eribulin or a treatment of their physician’s choice[7]. The control arm was designed to reflect various practices across continents. Almost all patients had received anthracyclines and taxanes and three fourths had also received capecitabine before study entry. The study showed a statistically significant benefit in OS for patients receiving eribulin treatment with an OS of 13.1 mo vs 10.6 mo [7]. No PFS benefit was demonstrated in the intention-to-treat analysis as per the independent review. Median PFS was 3.7 mo in the eribulin arm. Hematological toxicities, asthenia/fatigue and peripheral neuropathy were the most common toxicities in the eribulin arm. The second phase III trial was recently published and 1102 patients, who had previously received anthracyclines and taxanes, were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to eribulin or capecitabine[8]. The trial showed eribulin and capecitabine to be equally effective for both PFS and OS[8]. Median PFS was 4.1 mo in the eribulin arm in this study. Pooled results of these two randomized phase III studies have confirmed a statistically significant OS benefit in the eribulin arm with a median OS of 15.2 mo vs 12.8 mo in the control arm[9].

Interestingly, in the above pooled study, an a posteriori sub-group analysis showed that the eribulin OS benefit was consistent in all sub-types with the triple negative patients obtaining a slightly greater benefit from eribulin compared to control treatments[9]. In a retrospective study that included 133 patients, the clinical benefit of eribulin, especially in Her-2 negative patients, was confirmed[10]. In the first-line metastatic setting, a phase II trial that included only Her-2 negative patients (both Hormone Receptor positive and triple negative) outlined the activity of eribulin in these patients which resulted in a median PFS of 6.8 mo[11].

Our small retrospective analysis confirmed that approximately 50% of patients were alive at 13 mo as shown by the Kaplan-Meier curve (Figure 2). Median PFS was 3 mo and median OS was 7 mo in this heavily pre-treated population with a median of 4 previous lines of treatment (range 1 to 7). These results agree with those from the randomized trials and suggest that useful clinical activity can be expected in some patients who have received more than 3 previous lines of chemotherapy. The adverse effect profile of eribulin was also consistent with published data, with asthenia, neutropenia and peripheral neuropathy being the most common adverse effects. The patient population in our study was relatively young and only 3 patients were older than 65, however, studies have shown the feasibility of eribulin treatment in older patients[12].

Eribulin is added to the armamentarium of drugs with activity that may be used in metastatic breast cancer after anthracycline and taxane progression which may also include capecitabine[13], vinorelbine[14] and gemcitabine[15]. Nevertheless the short PFS highlights the need for more effective treatments or combinations.

This report was presented in part at the 26th International Congress on Anti-Cancer Treatment, Paris, France, Feb 3-5, 2015.

Eribulin is a synthetic analog of a natural marine product and is a new chemotherapeutic approved for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer.

This report discusses treatment with eribulin in clinical practice outside a clinical trial. It confirms the efficacy of the drug in the day to day clinical setting.

This is a confirmatory report of the usefulness of eribulin mesylate for advanced metastatic breast cancer.

Eribulin is an additional option for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer who have already received anthracyclines, taxanes and capecitabine.

Eribulin (previously known as E7389): A chemotherapy drug which is a microtubule inhibitor and a synthetic analog of the natural product halichondrin B isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria okadai.

The paper described the observed outcomes of Eribulin treatment on a few breast cancer patients, it is a well written paper with a clear information on the outcomes of the treatment. It is a topic of interest to the journal's readers.

| 1. | Hortobagyi GN, de la Garza Salazar J, Pritchard K, Amadori D, Haidinger R, Hudis CA, Khaled H, Liu MC, Martin M, Namer M. The global breast cancer burden: variations in epidemiology and survival. Clin Breast Cancer. 2005;6:391-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;64:52-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1440] [Cited by in RCA: 1518] [Article Influence: 126.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pean E, Klaar S, Berglund EG, Salmonson T, Borregaard J, Hofland KF, Ersbøll J, Abadie E, Giuliani R, Pignatti F. The European medicines agency review of eribulin for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: summary of the scientific assessment of the committee for medicinal products for human use. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4491-4497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Muñoz-Couselo E, Pérez-García J, Cortés J. Eribulin mesylate as a microtubule inhibitor for treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2011;4:185-192. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15860] [Cited by in RCA: 22829] [Article Influence: 1342.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Tan AR, Rubin EH, Walton DC, Shuster DE, Wong YN, Fang F, Ashworth S, Rosen LS. Phase I study of eribulin mesylate administered once every 21 days in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4213-4219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cortes J, O’Shaughnessy J, Loesch D, Blum JL, Vahdat LT, Petrakova K, Chollet P, Manikas A, Diéras V, Delozier T. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet. 2011;377:914-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 759] [Cited by in RCA: 847] [Article Influence: 56.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kaufman PA, Awada A, Twelves C, Yelle L, Perez EA, Velikova G, Olivo MS, He Y, Dutcus CE, Cortes J. Phase III open-label randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:594-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Twelves C, Cortes J, Vahdat L, Olivo M, He Y, Kaufman PA, Awada A. Efficacy of eribulin in women with metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148:553-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gamucci T, Michelotti A, Pizzuti L, Mentuccia L, Landucci E, Sperduti I, Di Lauro L, Fabi A, Tonini G, Sini V. Eribulin mesylate in pretreated breast cancer patients: a multicenter retrospective observational study. J Cancer. 2014;5:320-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McIntyre K, O’Shaughnessy J, Schwartzberg L, Glück S, Berrak E, Song JX, Cox D, Vahdat LT. Phase 2 study of eribulin mesylate as first-line therapy for locally recurrent or metastatic human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:321-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Muss H, Cortes J, Vahdat LT, Cardoso F, Twelves C, Wanders J, Dutcus CE, Yang J, Seegobin S, O’Shaughnessy J. Eribulin monotherapy in patients aged 70 years and older with metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2014;19:318-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Miller KD, Chap LI, Holmes FA, Cobleigh MA, Marcom PK, Fehrenbacher L, Dickler M, Overmoyer BA, Reimann JD, Sing AP. Randomized phase III trial of capecitabine compared with bevacizumab plus capecitabine in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:792-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1034] [Cited by in RCA: 964] [Article Influence: 45.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stravodimou A, Zaman K, Voutsadakis IA. Vinorelbine with or without Trastuzumab in Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Single Institution Series. ISRN Oncol. 2014;2014:289836. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Dranitsaris G, Beegle N, Kalberer T, Blau S, Cox D, Faria C. A comparison of toxicity and health care resource use between eribulin, capecitabine, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine in patients with metastatic breast cancer treated in a community oncology setting. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2015;21:170-177. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Gam LH, Nagata T, Sugawara I, Zhou M S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK