Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.112191

Revised: September 11, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 152 Days and 12.3 Hours

Kefir is a probiotic fermented milk product, distributed throughout the world from the North Caucasus, formed by fermenting milk with kefir grains. Kefir grains represent a striking example of microbial symbiosis between bacteria and fungi. Despite the extensive shifts in microbial composition during milk fer

Core Tip: Kefir grains are a unique symbiont of bacteria and yeast used as a starter for the production of a fermented milk drink with many beneficial properties. Bacterial and yeast components of the grains and kefir are actively studied for use in clinical medicine and in the development of new functional products, antimicrobial and probiotic drugs. This review introduces the history of the origin of kefir grains, various aspects of traditional and industrial use of kefir grains, properties and genetic characteristics of the microbial profile of kefir grains.

- Citation: Katchieva PK, Katchieva KK, Kipkeeva FI, Kharaeva ZF, Smeianov VV. Kefir revisited: Insights from the North Caucasus. World J Exp Med 2025; 15(4): 112191

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v15/i4/112191.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.112191

The burgeoning allure of natural compounds and their biological activities is strikingly evident in the exponential surge of scientific publications dedicated to this captivating domain. Numerous investigations are strategically directed towards identifying novel natural molecules with promising antitumor, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, an

In addition, the development of new fermented milk functional food products and studies of their effects on human health, mediated by microbiota and the immune system, are among the most important tasks in medicine and food technology. The microbiota of traditional fermented milk products represents a natural reservoir for isolating potentially probiotic strains. One of the most widely used carriers of probiotic microorganisms is kefir. In the beginning of the 20th century, Mechnikoff[7], one of the pioneers of probiotic therapy, recognized the health benefits of “kephir… the native drink of the mountaineers of the Caucasus”. However, Mechnikoff[8] was not quite an optimistic proponent of kefir consumption due to the presence of yeast, raising potential safety issues with alcoholic fermentation, citing the undefined microbial content of this product. He emphasized the health-promoting potential of traditional lactic acid bacteria-fermented dairy products, including kefir, and considered these effects to be primarily due to the ability of lactic acid to antagonize the intestinal “microbes of putrefication”, which would improve the body’s resistance. Yet, it was thought that a consortium of “special yeast” and lactic acid bacteria in kefir grains contributes to what is commonly considered to be a tasty and healthy fermented dairy product[9]. Kefir is a refreshing product resulting from mixed lactic acid and alcohol fermentation, with a homogeneous and slightly foamy consistency, reminiscent of liquid sour cream. To produce kefir, kefir grains are used as a starter. Kefir is a unique symbiont, and its indigenous properties are highly heterogeneous, as Mechnikoff[8] had postulated. Currently, the only method for obtain new batches of kefir is to grow and reproduce previous generations of the grains, as it is not possible to completely artificially reconstruct kefir grains in the laboratory[10].

To synthesize this review, we performed a meticulous search across several prominent repositories. The electronic databases PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information) and eLibrary.ru were queried for publications spanning all available dates, employing the keywords “milk kefir”, “kefir grain”, “kefir mushroom”. Furthermore, the card catalogs of Russian libraries were systematically examined to retrieve textbooks and methodological supplements related to food products, particularly those published during the Soviet era. Access to relevant dissertations was facilitated through a targeted search of the disserCat database of Russian scientific dissertations, utilizing analogous keywords.

The search of eLibrary.ru yielded 623 articles published between 2001 and 2025, comprising 551 primary research studies and 72 review articles. PubMed contributed 880 publications ranging from 1950 to 2025, consisting of 798 primary studies and 82 review articles. A total of 29 digitized textbooks and teaching aids pertaining to the food industry, published between 1879 and 1999, were identified within Russian library card catalogs. The disserCat database provided 286 dissertations dated from 1955 to 2024.

From this extensive collection, a curated selection of 104 primary studies, 10 textbooks on the food industry, and 4 dissertations were included in the final review. The inclusion criteria were rigorously defined to ensure relevance and scientific rigor: (1) Ethnographic data illuminating the origin of kefir grain, traditional kefir preparation methods, and local kefir grain preservation techniques; (2) Primary cultural and metagenomic investigations elucidating the composition of kefir and/or kefir grain; (3) Primary (laboratory, experimental, and clinical) and review studies focusing on the properties of kefir; and (4) Comparative analyses of the composition and properties of indigenous and technical kefir grain and/or kefir.

The natural history of the origin of kefir grains has not been fully elucidated, but the pastures around Mount Elbrus in southern Russia are considered their homeland. Here, kefir grains were first discovered in the folds of milk wineskins used by local residents. According to one version, milk from mountain meadows during transportation turned sour in a wineskin (gybyt - a bag made of sheep or goat skin) and, when washing the wineskin, kefir grains were found in its folds. Kefir grains were highly valued, respectfully called “white oxygen” and “millet of the prophet”, and original kefir was called “gypy ayran”. They began to grow fungi in a separate container, washing them daily and filling them with new milk[11]. According to another version, kefir grains arose from the long-term infusion of goat’s milk on pieces of calf’s stomach in a wooden container. Over time, accumulations of kefir grains formed on their walls[12,13].

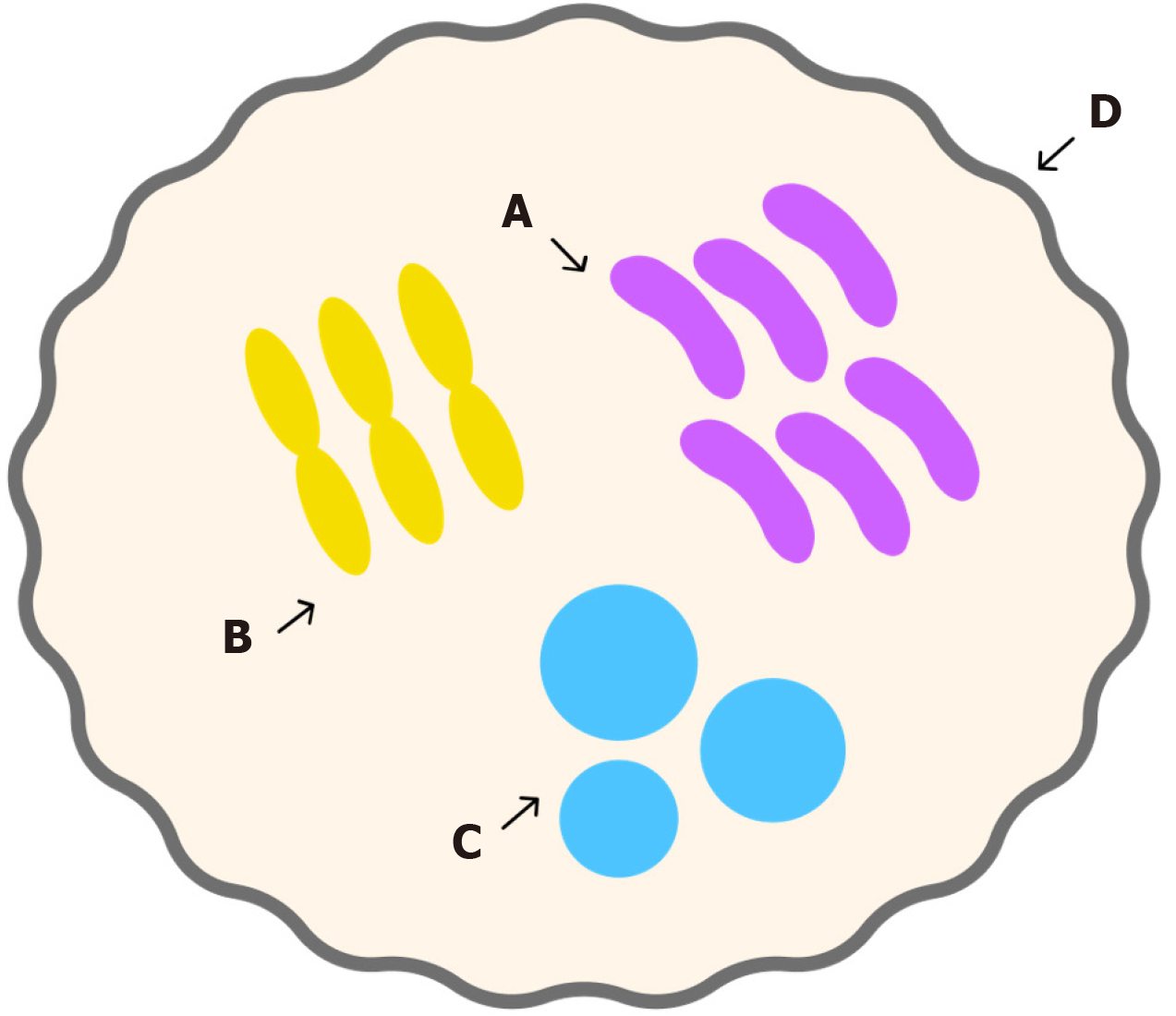

Kefir grains are a stable symbiotic formation resulting from a complex association of bacteria and yeast bound by a polysaccharide matrix (Figure 1)[14]. Kefiran, the matrix comprising polysaccharide, is a regular, moderately branched polymer, the repeating unit of which contains three glucose residues and three galactose residues[15]. When isolated state on nutrient media, polysaccharide (glycan) production decreases with successive passages, whereas under natural symbiotic conditions, active and continuous polysaccharide synthesis is maintained[16]. Kefir grains are cauliflower-like granules, with most microorganisms localized within the granule structure[15]. Their distinctive structure and properties are preserved through fermentation and passed on to subsequent generations of grains[17]. Although the shape and consistency may vary, kefir grains are generally soft-cartilaginous and elastic, with a lumpy or highly folded surface and irregular contours. Individual granules range in size from 1 mm to 6-7 cm or more[17]. Microorganisms are arranged in an ordered manner within the matrix, giving the grains their characteristically dense, compact appearance[15]. When crushed, the grains do not dissolve into a slimy mass but instead break into firm, elastic shreds similar in texture to the intact grain. In contrast, flabby grains, composed primarily of yeast cells with relatively few bacteria, ferment milk poorly, fail to multiply, gradually diminish in size, and are reported to eventually “melt and disappear”[18]. Kefir grains are living bodies capable of independent development and reproduction. Scanning electron microscopy showed that the kefir grain surface is represented by a close interweaving of threads of rod-shaped (long and curved) bacteria in a polysaccharide matrix, which forms a grain stroma that retains other microorganisms. Light microscopy revealed that, along with living cells, kefir grains also contain a large number of inactive cells that serve as growth factors for living cells[19].

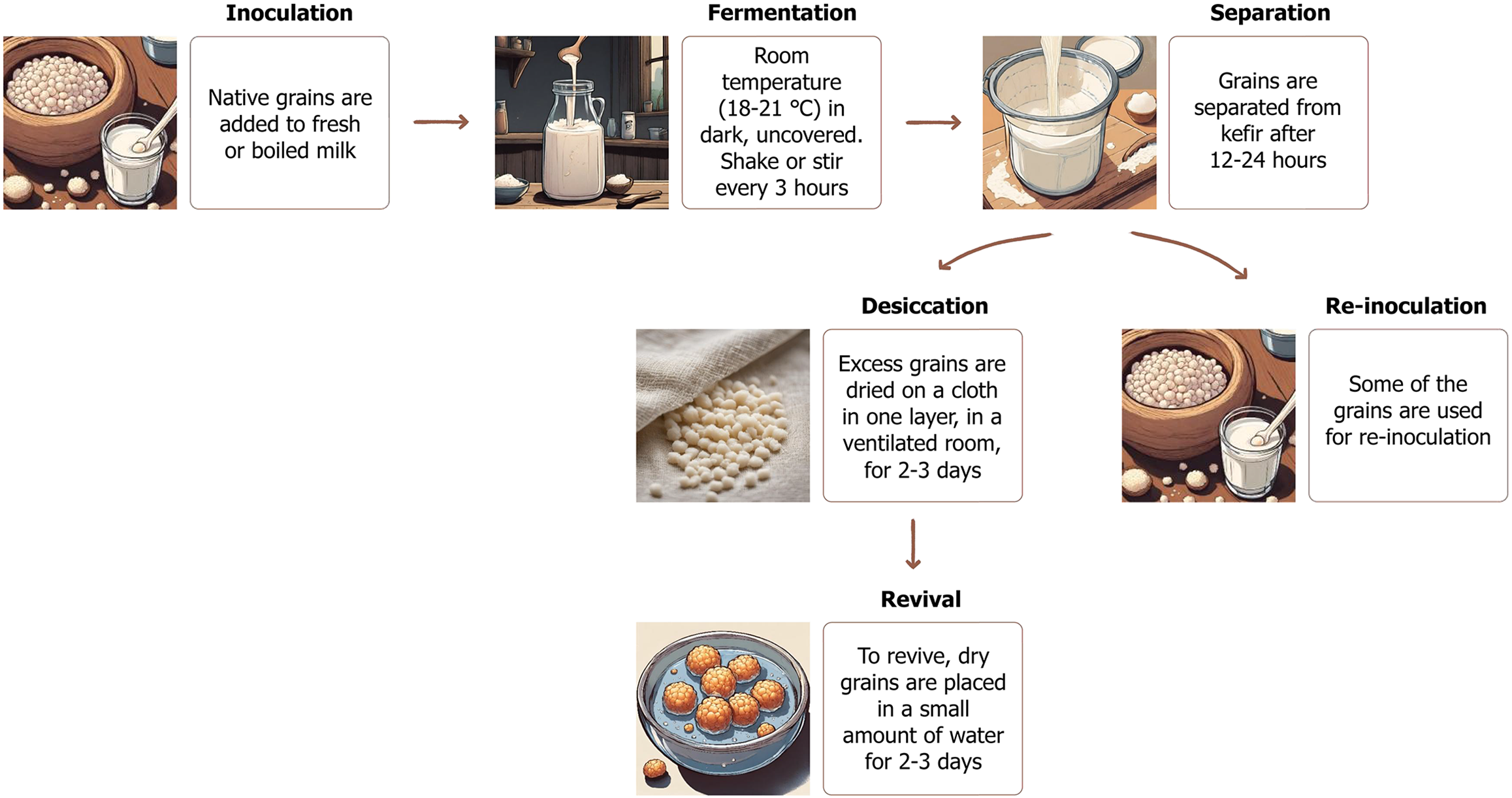

Fermented milk products were originally made using natural starters containing yeast and lactic acid bacteria, allowing milk, abundant in the spring-summer season, to be preserved for long periods[18]. Traditional kefir production does not involve boiling the milk; instead, the milk is filtered before kefir grains are added (Figure 2)[20]. For a long time, kefir was traditionally prepared in wineskins, which were hung or placed along the roadside opposite the house. Passersby customarily kicked the wineskin, providing aeration. The constant agitation mixed the milk with the starter culture, while exposure to sunlight maintained a warm temperature, together promoting more active fermentation. Sometimes the starter was not added at all, as kefir grains were already embedded in the folds of the wineskin. Later, fermentation shifted to the use of special clay jugs[21]. It was recommended that milk from the same cow be used, preferably with a low fat content. In this method, whole milk is left in a cold place for no more than 6 hours, after which the cream is removed and the skimmed portion is boiled and used for fermentation[18]. Although temperature fluctuations do not compromise grain viability, they do influence the rate and character of fermentation[18]. During fermentation, the grains require oxygen; therefore, the container must allow air exchange and should be covered with cloth or gauze rather than a tight lid[18]. Today, in the historical homeland of Caucasian kefir, traditional fermentation methods are preserved, though wooden or glass vessels are also used. Homemade kefir is considered best consumed within the first 2 days. After fermentation and within 24 hours after inoculation, lactobacilli reach approximately 108 CFU/mL, while yeast and acetic acid bacteria reach about 105 CFU/mL and 106 CFU/mL, respectively. With continued refrigeration, lactic acid bacteria gradually decline[22].

Excess kefir grains are stored dry. Native grains are naturally dried in a well-ventilated area or in sunlight, arranged in a single layer on cloth or paper. During drying, the grains lose up to 90% of their water content and shrink into small yellow lumps of various sizes and irregular shapes. The dried grains feel greasy, are hard in texture, and break into rounded fragments when pressure is applied[18]. At this stage, the microorganisms within the grains are thought to enter a state of anabiosis, as the lack of moisture markedly reduces metabolic activity. The viability of microorganisms in dry kefir grains remain stable for more than 6 months[23]. However, the recommended maximum storage time is 2 years; after 3 years, kefir yeasts reportedly lose their ability to ferment milk[18]. Before use, dry grains must be “revitalized”. This is accomplished by soaking them in clean water for 2-3 days, with regular changes of water[24]. The first batches of milk fermented with revitalized grains do not produce true kefir; only after 6-10 days of fermentation do the grains regain full activity and yield a characteristic kefir beverage[18].

It is not recommended to wash the grains with water or milk during the cultivation process, as it causes leaching of a significant part of the beneficial microflora and disruption of starter composition stability, which leads to deterioration in quality[25]. It is recommended to carefully rinse the grains in clean boiled water at room temperature once a week, while avoiding mechanical stress and changing the water several times[23].

Kefir grains can acquire defects, including mucus, mold, and contamination with Escherichia coli[18]. Enterobacteria bacteria are foreign microorganisms for kefir. Oidium spp. molds (e.g., Oidium lactis) can multiply on the surface during long-term storage of kefir in the form of filmy, matte colonies and reduce the concentration of bactericidal substances of kefir during its storage[26,27].

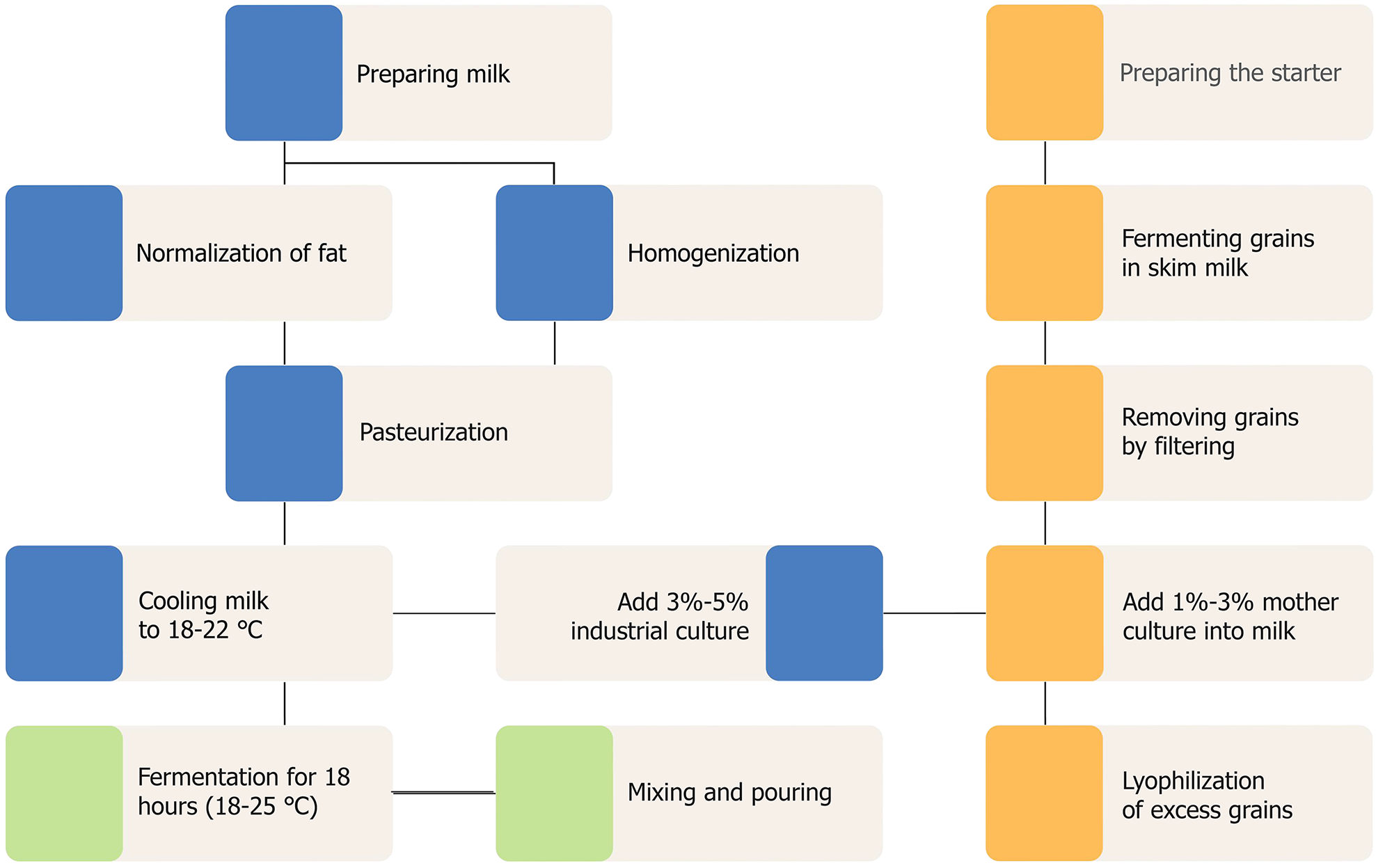

Unlike traditional kefir, which is made by inoculating kefir grains into milk, the dairy industry uses mother starters. To obtain a mother starter, active kefir grains are placed in pasteurized skim milk at 19-21 °C at a ratio of 1:20[23], and then transferred to milk at the ratio of one part grains to 30-50 parts milk[26]. After 15-18 hours, the starter is thoroughly mixed and filtered through a metal sieve. The grains remaining on the sieve are again placed into fresh pasteurized and cooled milk, and the resulting mother starter is used to prepare kefir (Figure 3)[26]. The production requires a large quantity of grains, so they have to be “multiplied”[23]. A deficit of the mother culture can occur with large-scale production, so it must to be used to prepare a new production starter. The production starter is prepared by fermenting pasteurized milk at 18-20 °C with the addition of 5% mother starter. To prepare kefir directly, 3%-5% of industrial starter culture is added to milk[28] and fermented at a temperature of 18-22 °C for 16-18 hours[26]. Considering that acetic acid bacteria increase the viscosity of kefir, it is recommended to increase the temperature of the cultivation of kefir grains to 25 °C in the spring to increase acetic acid bacteria development[25]. To preserve the long-term “performance” of the grains, it is recommended to use milk from different suppliers. For long-term storage, the grains may be frozen or lyophilized[23].

Large-scale production of kefir is currently performed by adding 1%-3% liquid mother culture to milk[29] or 3%-5% industrial kefir starter[25,26]. Additionally, the variable nature of the organisms and metabolites present in kefir fermented with kefir grains has led producers to use frozen or freeze-dried starters produced by mixing pure cultures (the “direct addition” method)[30,31].

The first publications on Caucasian kefir as a medicinal product appeared in 1882, where the drink was called “kapir”, according to the mountaineers who gave the grains to the researcher. Initially, kefir prepared with grains was re

The health-promoting effects of kefir on the intestinal microbiota has been established by an increasing number of studies[35-37], which have demonstrated the ability of kefir to suppress the growth of potentially pathogenic microorganisms and restore the counts of beneficial bacteria[38]. The consumption of kefir has an inhibitory effect on the growth of Candida yeast and Proteus enterobacteria in children and has a pronounced antagonistic activity against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridia difficile, and Salmonella thyphimurium[39-41].

Carefully selected doses of kefir can reduce the inflammatory process in rat models of colitis[42,43]. The positive effect of kefir on intestinal microflora in colitis and Crohn’s disease was described in a randomized controlled trial by Yılmaz et al[44]. Kefir fermented with grains significantly improved the gut microbiome wellness index in critically ill patients[45]. Kefir reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and accelerates colonic transit in patients with chronic constipation[46,47]. At the same time, Merenstein et al[48] observed no statistically significant impact of com

The anticancer activities of kefir and its components have been studied extensively and are considered to be primarily due to systemic effects resulting from the normalization of intestinal microbiota and immune system parameters[49-59]. The supporting effect of kefir has been demonstrated in laboratory and experimental studies on Ehrlich ascites carcinoma, colorectal cancer, acute erythroleukemia, T-cell lymphoma, glioblastoma and breast cancer[50-58]. Kefir has antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects on colon adenocarcinoma cells[49] and HTLV-1-negative malignant T-lymphocytes[58]. Kefir produced from natural grains inhibits the growth of the potentially pathogenic and carcinogenic mold yeast Trichoderma koningii[59]. In contrast, Zanardi et al[60] found that kefir increased macroscopic neoplastic lesions and increased the abundance of Firmicutes and Clostridium in rats with colorectal cancer. In a clinical study by Topuz et al[61], kefir consumption at the mentioned doses had no statistically significant effect on serum proinflammatory cytokine levels and on the incidence of mucositis development in cancer patients.

The immunomodulatory effects of kefir have been primarily characterized in animal models. Kefir’s immunomodulatory influence manifests primarily through the potentiation of phagocyte activity, induction of immunoglobulin A (IgA) synthesis, and the augmentation of Th1 cytokine production, exhibiting a nuanced anti-inflammatory dimension via the upregulation of interleukin (IL)-10. Studies have demonstrated that murine subjects, provided with ad libitum access to either raw or pasteurized kefir, exhibited a discernible elevation in IgA-producing cell populations and macrophage phagocytic efficacy within both intestinal and bronchial tissues, suggesting a systemic reach of kefir’s immunological effects[62].

Among other immunotropic effects, the anti-allergic effect of kefir may be associated with the direct activation of mast cells involved in immediate-type, hypersensitivity allergic reactions[63]. Kefir consumption in asthmatic mice resulted in decreased eosinophils and IgE status in bronchiolar lavage fluids[64]. Liu et al[65] found lower serum IgE and IgG1 levels in kefir-fed mice and increased fecal Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium counts compared to placebo.

Similar immunomodulatory and antiallergic effects were demonstrated in experiments using kefiran or lactic acid bacteria isolated from kefir grain (L. kefiri, L. kefiranofaciens)[66-72]. L. kefiri CIDCA 8348, administered over a period of 21 days, significantly increased fecal sIgA concentrations and enhanced IL-10 gene expression within the ileum and mesenteric lymph nodes of healthy Swiss mice[66]. Further investigation into kefiran, an exopolysaccharide derived from kefir grains, revealed that ad libitum administration (300 mg/L) over a 48-hour period in mice resulted in increased IgA+ cells and macrophages within the lamina propria. Moreover, a consistent upward trajectory was observed in the enumeration of macrophages, along with both total and activated dendritic cells within Peyer’s patches following a 7-day treatment regimen. Concurrently, peritoneal macrophage counts also increased after the same 7-day period[67].

Clinical trials of the immunomodulatory effect of kefir have shown heterogeneous results. Pražnikar et al[73] observed no significant changes in serum C-reactive protein (CRP) or adiponectin concentrations following kefir administration, despite noting a decrease in serum zonulin, a marker of intestinal permeability. In patients with metabolic syndrome, Bellikci-Koyu et al[74] found that kefir consumption decreased serum concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, and interferon-gamma. However, a concurrent decrease in anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 levels was also observed. The same study demonstrated an increase in serum apolipoprotein A1 concentrations compared to placebo, but no significant differences were found in serum apolipoprotein B or low-density lipoprotein concentrations.

Kefir reduces cholesterol levels in the blood serum, which is also due to kefiran content in kefir[75,76]. In vitro studies demonstrated the cholesterol-lowering potential of microorganisms isolated from natural kefir grains[77]. However, an in vitro analysis evaluating the hypocholesterolemic potential of lactic acid bacteria isolates from Lactococcus species and yeasts from 16 commercial multistrain starter cultures dedicated to kefir production revealed a comparatively limited capacity for cholesterol binding under simulated digestive tract conditions[78]. In a randomized trial by Bourrie et al[79], consumption of kefir fermented with traditional culture reduced low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), while commercial kefir consumption increased TNF-α. Pitched kefir consumption resulted in a greater decrease in IL-8, CRP, VCAM-1, and TNF-α compared to commercial kefir consumption. In another randomized trial, commercial kefir had no effect on total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglyceride concentrations nor on cholesterol fractional synthesis rates after 4 weeks of supplementation[80].

Research into the impact of kefir and its components on metabolic syndrome, with a specific focus on serum glucose levels, has yielded promising results. A study involving male hyperglycemic Wistar rats found that kefir consumption decreased serum glucose concentrations and increased serum IL-10 concentrations[81]. Urdaneta et al[82] further substantiated the blood glucose-lowering effects of kefir in rats. This hypoglycemic effect has been observed in conjunction with an oral glucose tolerance test, where kefir-fed rats exhibited reduced glycogen concentrations in renal tubules and diminished superoxide ion concentrations in the renal cortex[83].

Kefir improved fatty liver syndrome on body weight, energy expenditure and basal metabolic rate in mice with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[84]. Furthermore, kefir exhibits antioxidant activity; therefore, it may control oxidative stress[85,86]. Güven et al[87] demonstrated that kefir had a higher antioxidant effect than vitamin E. Additionally, kefir has an antihypertensive effect[88-90]. Kefir has antimicrobial and healing effects on skin lesions and chemical esophagitis in rats[91,92]. Kefiran demonstrated an anti-aging effect by increasing the resistance of Caenorhabditis elegans to heat stress and extending their lifespan(Table 1)[93].

| Biological activity | Ref. |

| Antagonistic activity against pathogenic microorganisms | [35-41] |

| Reducing the inflammatory process in colitis | [42-44] |

| Improvement in the GMWI | [45] |

| Reducing symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation | [46,47] |

| Anticancer effect | [49-59] |

| Immunomodulatory and anti-allergic effect | [62-72,74] |

| Hypocholesterolemic effect | [75-79] |

| Glucose-lowering effect | [81,82] |

| Improving outcomes in NAFLD | [84] |

| Antioxidant activity | [85-87] |

| Antihypertensive effect | [88-90] |

| Healing effect on skin lesions and chemical esophagitis | [91,92] |

| Anti-aging effect | [93] |

The microbial profile of kefir grains differs in species composition and ratio of microorganisms. Despite the distant geographical origin of the kefir grains studied, the presence of one or more dominant species in kefir grain communities from different geographical locations indicates high homogeneity among kefir grains[94,95]. It was previously believed that milk in which kefir grains were cultivated contained the same microflora as kefir grains. However, it has since been established that the microbial diversity of kefir differs from kefir grains[96]. The main microbial components pass from the kefir grain into the liquid phase on the first day of cultivation, while acetic acid bacteria do not appear until the second day[19]. In addition, the microflora of kefir remains relatively stable in different periods of the year. In the summer, the number of thermophilic lactic acid bacteria slightly increases, and in spring, the acetic acid bacterial content decreases[26].

Cultural studies to identify the microbial components of kefir grains are limited in that they only identify species that can grow on the specific medium used[97-101]. A comprehensive analysis of communities, independent of cultivation conditions, is possible using molecular methods. Kefir fermentation has a peculiar compositional dynamic in which the grain remains unchanged with a constant dominance of Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens, while the milk fraction is successively colonized[102]. In determining the variability of the microbial population of kefir during a 24-hour fermentation, me

Lactobacillus was the dominant bacterial genus in a metagenomic study of kefir grains from various geographic origins[94,103,104], and the main bacterial species in kefir grains was Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens[105-107]. The fungal population of grains were primarily represented by the genera Saccharomyces and Kazachstania[9,103,108].

In rare cases, representatives of the Bifidobacterium genus have been found in kefir grain samples[10,103,109,110]. During our own research, we performed genetic characterization of the microbial composition of autochthonous kefir grains obtained in the region of their geographical origin of Caucasian kefir - the Karachay-Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkarian republics of the North Caucasus (Mount Elbrus region). The largest family of bacteria was Lactobacillaceae, which constituted more than 70% of the populations in all grains. Representatives of Pseudomonadaceae, Streptococcaceae, Burkholderiaceae, Propionibacteriaceae, Acetobacteraceae, Leuconostocaceae, Acidobacteriaceae were also present in most grains. The dominant bacterial species in all samples was Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens. In addition, notable species of bacteria from the family Acidobacteriaceae (Granulicella paludicola, Terriglobus saanensis, Edaphobacter flagellates) and Magnetofaba australis from the Magnetococcaceae family were identified. The most common fungal phylum in all grains was Ascomycota. The dominant fungal genera were Galactomyces, Kazachstania, Kluyveromyces and Saccharomyces[111].

Two studies compared the differences between traditional (homemade) and industrial kefir (Table 2)[109,112]. According to Kazou et al[109], traditional kefir contained more mesophilic lactic acid bacteria (LAB) (6.50-9.60 log CFU mL-1) and thermophilic LAB (6.60 log CFU mL-1 to 9.20 log CFU mL-1) compared to industrial kefir [(6.38-9.15) log CFU mL-1 and (5.32-8.60) log CFU mL-1, respectively]. Non-Starter lactic acid bacteria and Enterococci were also predominant in traditional kefir and amounted to (6.11-8.56) log CFU mL-1 and (3.48-5.60) log CFU mL-1 vs (6.41-8.33) log CFU mL-1 and (2.48-0.81) log CFU mL-1 in industrial kefir. Yeasts were present in all traditional kefir samples and only half of the industrial drink samples. Alpha-diversity indices for bacterial communities were higher in traditional kefir than in industrial kefir (Shannon index 1.25-2.1 vs 0.8-1.25; inverse Simpson indexes 2.3-4.9 vs 1.7-2.2). In a study by Nejati et al[112] using qPCR, L. kefiranofaciens (1.E + 08), L. kefiri (1.E + 08), L. lactis (1E + 09), L. mesenteroides (1E + 08) were present in traditional grain-fermented kefir, whereas only L. lactis (1E + 09), L. mesenteroides [(1E + 06) – (1E + 07)] were observed in commercial kefir.

| Parameters | Traditional (home-made) kefir | Industrial kefir | Method of analysis | Ref. |

| Mesophilic LAB | (6.50-9.60) log CFU mL-1 | (6.38-9.15) log CFU mL-1 | Microbiological analysis | [109] |

| Thermophilic LAB | (6.60-9.20) log CFU mL-1 | (5.32-8.60) log CFU mL-1 | Microbiological analysis | [109] |

| NSLAB | (6.11-8.56) log CFU mL-1 | (6.41-8.33) log CFU mL-1 | Microbiological analysis | [109] |

| Enterococci | (3.48-5.60) log CFU mL-1 | (2.48-0.81) log CFU mL-1 | Microbiological analysis | [109] |

| Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens | 1.Е + 08 | - | qPCR | [112] |

| Lactobacillus kefiri | 1.Е + 0.8 | - | qPCR | [112] |

| Shannon’s alpha diversity index | 1.25-2.1 | 0.8-1.25 | Metagenomics analysis | [109] |

| Inverse Simpson index | 2.3-4.9 | 1.7-2.2 | Metagenomics analysis | [109] |

| Yeasts | Found in 100% of samples | Found in 50% of samples | Microbiological analysis | [109] |

As kefir grains are currently spread throughout many countries and are produced on an industrial scale, the medical community has declared the need to renew supplies of indigenous kefir grains from throughout the North Caucasus[113]. This was explained by the degeneration of kefir grains due to exposure to climatic conditions that are different from those found in the Alpine region and a decrease in the number of microorganisms during long-term kefir production using a continuous method[20,114]. It was contentiously proposed that to maintain starter cultures in the most active state, it is necessary to replace kefir grains to prevent changes in the biological properties of starter microorganisms during their long-term cultivation and storage[26].

Although commercial kefir-like products may provide health benefits, their current level of compliance requires better monitoring[115]. In addition, the microbial composition of commercial kefir-like products differs from kefir obtained by fermenting with indigenous kefir grains. Accordingly, commercial kefir may not fully provide the declared beneficial properties[107,116,117]. The microbial composition of products fermented with lyophilized bacterial starter appears to be inferior in terms of the titers of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts as compared to kefir fermented with kefir grains[39,118].

There is an obvious need to conduct comparative studies of the composition of indigenous samples of kefir grains obtained from the sites of its historical origin, namely in the mountain villages of the North Caucasus, in particular the Karachay-Cherkess Republic and Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, with industrial starter cultures using modern cultural and metagenomic methods. The results of such work will allow us to establish the core microbiome of native kefir grains, more accurately suggest the evolutionary genesis of kefir grains, characterize important members or consortia of grains, and consider them for the development of new functional products. Due to current developments in metagenomics, Mechnikoff’s safety concerns on kefir can be overcome, and microbiologically safe composition of kefir grains will be found.

| 1. | Ekiert HM, Szopa A. Biological Activities of Natural Products. Molecules. 2020;25:5769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Arulselvan P, Fard MT, Tan WS, Gothai S, Fakurazi S, Norhaizan ME, Kumar SS. Role of Antioxidants and Natural Products in Inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:5276130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 63.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Naeem A, Hu P, Yang M, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhu W, Zheng Q. Natural Products as Anticancer Agents: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Molecules. 2022;27:8367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Guo X, Yin X, Liu Z, Wang J. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Pathogenesis and Natural Products for Prevention and Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Bontempo P, De Masi L, Rigano D. Functional Properties of Natural Products and Human Health. Nutrients. 2023;15:2961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Savaiano DA, Hutkins RW. Yogurt, cultured fermented milk, and health: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2021;79:599-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mechnikoff E. The prolongation of life. Nature. 1908;77:289-290. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mechnikoff E. The nature of man. Nature. 1938;142:1100. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zavadovsky BM. On fermentation. Moscow: Russian State Library Electronic Catalog, 1925. |

| 10. | Walsh AM, Crispie F, Kilcawley K, O'Sullivan O, O'Sullivan MG, Claesson MJ, Cotter PD. Microbial Succession and Flavor Production in the Fermented Dairy Beverage Kefir. mSystems. 2016;1:e00052-e00016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tekeev KM. Karachais and Balkars: Traditional Life Support System. Moscow: Abstract of the dissertation. 1991. Available from: https://rusneb.ru/catalog/000199_000009_000037774/. |

| 12. | Filchakova SA. National fermented milk drink - kefir. Whole milk production, 2010; 3: 34-35. Available from: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=25326252. |

| 13. | Budinov LT. Milk and dairy products. Moscow: Record. 1910: 115. Available from: https://www.booksite.ru/fulltext/125247/text.pdf. |

| 14. | Vorobieva AI. Component composition of kefir grains. Leningrad: Dissertation of a candidate of biological sciences. 1989. Available from: https://search.rsl.ru/ru/record/01008156447?ysclid=ls1kzr1ne0202040934. |

| 15. | Vorobieva AI, Vitovskaya GA, Shashkov AS, Knirel YuA, Paramonov NA. The structure of glucogalactan in kefir grains. Bioorganic chemistry. 1990; 16: 80-85. Available from: http://www.rjbc.ru/arc/16/6/0808-0817.pdf. |

| 16. | Khamnaeva NI, Pavlova TG. On the directions of using the microbial association of kefir fungi. Proceedings of the conference: Successes of modern natural science. 2010; 3: 98-99. Available from: https://s.natural-sciences.ru/pdf/2010/3/53.pdf. |

| 17. | Shevchenko VV, Ermilova IA, Vytovtov AA, Polyak ES. Merchandising and examination of consumer goods. Moscow: Infra-M. 2003: 99. Available from: https://mysocrat.com/book-card/14917-tovarovedenie-i-ehkspertiza-potrebitelskih-tovarov/. |

| 18. | Dmitriev VN. Kefir. Healing drink from cow's milk. 8th edition. St. Petersburg: Public Benefit, 1912: 237. |

| 19. | Khokhlacheva AA, Egorova MA, Suzina NE, Gradova NB. Study of the microbial composition of the functional activity of the culture liquid of kefir fungi (starter cultures). Bulletin of the Gorsk State Agrarian University. 2014; 52: 228-234. Available from: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=23101952. |

| 20. | Khadzhieva MKh. Traditional food system of Karachais and Balkars in the 19th - 20th centuries. Аbstract dissertation for an academic degree for a candidate of historical sciences, Nalchik. 2008: 32. Available from: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=15924750. |

| 21. | Alexandrina EV, Kanev PN, Kazantseva ES. The history of the emergence of fermented milk drinks. Useful properties of kefir. Youth and Scienc. 2018; 8: 22. Available from: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=36903428. |

| 22. | Irigoyen A. Microbiological, physicochemical, and sensory characteristics of kefir during storage. Food Chem. 2005;90:613-620. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Glazachev VV. Fermented milk products technology. Moscow: Food Industry. 1968: 378. Available from: https://www.studmed.ru/view/glazachev-vv-tehnologiya-kislomolochnyh-produktov_596b728be12.html. |

| 24. | Barabanshchikov NV. Dairy matter. Moscow: Kolos. 1983: 565. Available from: https://www.studmed.ru/barabanschikov-n-v-molochnoe-delo_4c86d2d9bf1.html. |

| 25. | Bannikova LA, Koroleva NS, Semenikhina VF. Microbiological foundations of dairy production: a reference book. Moscow: Agropromizdat. 1987: 459. Available from: http://www.bibliotekar.ru/5-mikrobiologiya-moloka/. |

| 26. | Stepanenko PP. Microbiology of milk and dairy products. Moscow Region: Sergiev Posad LLC. 1999: 513. Available from: https://microbius.ru/library/p-p-stepanenko-mikrobiologiya-moloka-i-molochnyh-produktov. |

| 27. | Bukanova VI. Kefir lactic-fermenting yeast and their importance for its quality. Moscow: Director of the competition for Candidate of Technical Science. 1955. Available from: https://www.dissercat.com/content/laktozosbrazhivayushchie-drozhzhi-kefira-i-ikh-znachenie-dlya-ego-kachestva. |

| 28. | Tverdokhleb GV, Dilanyan ZKh, Chekulaeva LV, Shiler GG. Milk and dairy products technology. Moscow: Agropromizdat. 1991: 614. Available from: https://www.studmed.ru/tverdohleb-gv-dilanyan-zh-chekulaeva-lv-shiler-gg-tehnologiya-moloka-i-molochnyh-produktov_28de5d620f3.html. |

| 29. | Stepanova LI. Dairy production technologist’s handbook. Technology and recipes. S. Petersburg: GIORD. 1999: 384. Available from: https://publ.lib.ru/ARCHIVES/S/STEPANOVA_Larisa_Ivanovna/_Stepanova_L.I..html. |

| 30. | Bourrie BC, Willing BP, Cotter PD. The Microbiota and Health Promoting Characteristics of the Fermented Beverage Kefir. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Pim VH. Starter culture compositions. United States Patent US10370636B2. 2019. |

| 32. | Krus GN, Tinyakov VG, Fofanov YuF. Milk technology and equipment for dairy industry enterprises. Moscow: Agropromizdat. 1986: 450. Available from: https://obuchalka.org/20201008125743/tehnologiya-moloka-i-oborudovanie-predpriyatii-molochnoi-promishlennosti-krus-g-n-tinyakov-v-g-fofanov-u-f-1986.html. |

| 33. | Shulga NM. A modern view of kefir microflora and technology. Products and ingredients. 2011; 3: 52-54. Available from: https://studylib.ru/doc/2286282/kefir--sovremennyj-vzglyad-na-mikrofloru-i-tehnologiyu. |

| 34. | Koroleva NS. Technical microbiology of whole milk products: scientific publication. Moscow: Food Industry. 1975: 349. Available from: https://rusneb.ru/catalog/002072_000044_ARONB-RU_%D0%90%D1%80%D1%85%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B3%D0%B5%D0%BB%D1%8C%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%8F+%D0%9E%D0%9D%D0%91_DOLIB_-405495/?ysclid=ls1kayn8ua178161463. |

| 35. | Santos A, San Mauro M, Sanchez A, Torres JM, Marquina D. The antimicrobial properties of different strains of Lactobacillus spp. isolated from kefir. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2003;26:434-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kairey L, Leech B, El-Assaad F, Bugarcic A, Dawson D, Lauche R. The effects of kefir consumption on human health: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Rev. 2023;81:267-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hamet MF, Medrano M, Pérez PF, Abraham AG. Oral administration of kefiran exerts a bifidogenic effect on BALB/c mice intestinal microbiota. Benef Microbes. 2016;7:237-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Franco MC, Golowczyc MA, De Antoni GL, Pérez PF, Humen M, Serradell MLA. Administration of kefir-fermented milk protects mice against Giardia intestinalis infection. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1815-1822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kharitonov VD, Rozhkova IV, Semenikhina VF, Makeeva IA. What product should be called kefir. Dairy industry, 2010; 4: 57-58. Available from: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=14613605. |

| 40. | Cevikbas A, Yemni E, Ezzedenn FW, Yardimici T, Cevikbas U, Stohs SJ. Antitumoural antibacterial and antifungal activities of kefir and kefir grain. Phytother Res. 1994;8:78-82. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kaledina MV, Fedosova AN, Baydina IA. Antipathogenic and immunomodulatory activity of national drinks. Food industry. 2019; 10: 72-75. Available from: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=41326590. |

| 42. | Senol A, Isler M, Sutcu R, Akin M, Cakir E, Ceyhan BM, Kockar MC. Kefir treatment ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:13020-13029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Sevencan NO, Isler M, Kapucuoglu FN, Senol A, Kayhan B, Kiztanir S, Kockar MC. Dose-dependent effects of kefir on colitis induced by trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid in rats. Food Sci Nutr. 2019;7:3110-3118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yılmaz İ, Dolar ME, Özpınar H. Effect of administering kefir on the changes in fecal microbiota and symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease: A randomized controlled trial. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30:242-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Gupta VK, Rajendraprasad S, Ozkan M, Ramachandran D, Ahmad S, Bakken JS, Laudanski K, Gajic O, Bauer B, Zec S, Freeman DW, Khanna S, Shah A, Skalski JH, Sung J, Karnatovskaia LV. Safety, feasibility, and impact on the gut microbiome of kefir administration in critically ill adults. BMC Med. 2024;22:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Pilipenko VI, Burliaeva EA, Shakhovskaia AK, Isakov VA. [Efficacy of using inulin fortified fermented milk products in patients with functional constipation]. Vopr Pitan. 2009;78:56-61. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Turan İ, Dedeli Ö, Bor S, İlter T. Effects of a kefir supplement on symptoms, colonic transit, and bowel satisfaction score in patients with chronic constipation: a pilot study. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25:650-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Merenstein DJ, Foster J, D'Amico F. A randomized clinical trial measuring the influence of kefir on antibiotic-associated diarrhea: the measuring the influence of Kefir (MILK) Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:750-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Khoury N, El-Hayek S, Tarras O, El-Sabban M, El-Sibai M, Rizk S. Kefir exhibits antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects on colon adenocarcinoma cells with no significant effects on cell migration and invasion. Int J Oncol. 2014;45:2117-2127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Jenab A, Roghanian R, Ghorbani N, Ghaedi K, Emtiazi G. The Efficacy of Electrospun PAN/Kefiran Nanofiber and Kefir in Mammalian Cell Culture: Promotion of PC12 Cell Growth, Anti-MCF7 Breast Cancer Cells Activities, and Cytokine Production of PBMC. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:717-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | de Moreno de Leblanc A, Matar C, Farnworth E, Perdigón G. Study of immune cells involved in the antitumor effect of kefir in a murine breast cancer model. J Dairy Sci. 2007;90:1920-1928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Kubo M, Odani T, Nakamura S, Tokumaru S, Matsuda H. [Pharmacological study on kefir--a fermented milk product in Caucasus. I. On antitumor activity (1)]. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1992;112:489-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Brasiel PGA, Dutra Medeiros J, Costa de Almeida T, Teodoro de Souza C, de Cássia Ávila Alpino G, Barbosa Ferreira Machado A, Dutra Luquetti SCP. Preventive effects of kefir on colon tumor development in Wistar rats: gut microbiota critical role. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2025;16:e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Brandi J, Di Carlo C, Manfredi M, Federici F, Bazaj A, Rizzi E, Cornaglia G, Manna L, Marengo E, Cecconi D. Investigating the Proteomic Profile of HT-29 Colon Cancer Cells After Lactobacillus kefiri SGL 13 Exposure Using the SWATH Method. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2019;30:1690-1699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Zeng X, Jia H, Zhang X, Wang X, Wang Z, Gao Z, Yuan Y, Yue T. Supplementation of kefir ameliorates azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium induced colorectal cancer by modulating the gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2021;12:11641-11655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 56. | Jalali F, Sharifi M, Salehi R. Kefir induces apoptosis and inhibits cell proliferation in human acute erythroleukemia. Med Oncol. 2016;33:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Fatahi A, Soleimani N, Afrough P. Anticancer Activity of Kefir on Glioblastoma Cancer Cell as a New Treatment. Int J Food Sci. 2021;2021:8180742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Maalouf K, Baydoun E, Rizk S. Kefir induces cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in HTLV-1-negative malignant T-lymphocytes. Cancer Manag Res. 2011;3:39-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Erdogan FS, Ozarslan S, Guzel-Seydim ZB, Kök Taş T. The effect of kefir produced from natural kefir grains on the intestinal microbial populations and antioxidant capacities of Balb/c mice. Food Res Int. 2019;115:408-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Zanardi KR, Grancieri M, Silva CW, Trivillin LO, Viana ML, Costa AGV, Costa NMB. Functional effects of yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius) and kefir on systemic inflammation, antioxidant activity, and intestinal microbiome in rats with induced colorectal cancer. Food Funct. 2023;14:9000-9017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Topuz E, Derin D, Can G, Kürklü E, Cinar S, Aykan F, Cevikbaş A, Dişçi R, Durna Z, Sakar B, Saglam S, Tanyeri H, Deniz G, Gürer U, Taş F, Guney N, Aydiner A. Effect of oral administration of kefir on serum proinflammatory cytokines on 5-FU induced oral mucositis in patients with colorectal cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:567-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Vinderola CG, Duarte J, Thangavel D, Perdigon G, Farnworth E, Matar C. Distal Mucosal Site Stimulation by Kefir and Duration of the Immune Response. Eur J Inflamm. 2005;3:63-73. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Furuno T, Nakanishi M. Kefiran suppresses antigen-induced mast cell activation. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35:178-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Lee MY, Ahn KS, Kwon OK, Kim MJ, Kim MK, Lee IY, Oh SR, Lee HK. Anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic effects of kefir in a mouse asthma model. Immunobiology. 2007;212:647-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Liu J, Wang S, Chen M, Yueh P, Lin C. The anti‐allergenic properties of milk kefir and soymilk kefir and their beneficial effects on the intestinal microflora. J Sci Food Agric. 2006;86:2527-2533. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 66. | Carasi P, Racedo SM, Jacquot C, Romanin DE, Serradell MA, Urdaci MC. Impact of kefir derived Lactobacillus kefiri on the mucosal immune response and gut microbiota. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:361604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Medrano M, Racedo SM, Rolny IS, Abraham AG, Pérez PF. Oral administration of kefiran induces changes in the balance of immune cells in a murine model. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:5299-5304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Vinderola G, Perdigón G, Duarte J, Farnworth E, Matar C. Effects of the oral administration of the exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens on the gut mucosal immunity. Cytokine. 2006;36:254-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Vinderola G, Perdigon G, Duarte J, Thangavel D, Farnworth E, Matar C. Effects of kefir fractions on innate immunity. Immunobiology. 2006;211:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Hong W, Chen H, Chen Y, Chen M. Effects of kefir supernatant and lactic acid bacteria isolated from kefir grain on cytokine production by macrophage. Int Dairy J. 2009;19:244-251. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Hong WS, Chen YP, Chen MJ. The antiallergic effect of kefir Lactobacilli. J Food Sci. 2010;75:H244-H253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Hong WS, Chen YP, Dai TY, Huang IN, Chen MJ. Effect of heat-inactivated kefir-isolated Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens M1 on preventing an allergic airway response in mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:9022-9031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Pražnikar ZJ, Kenig S, Vardjan T, Bizjak MČ, Petelin A. Effects of kefir or milk supplementation on zonulin in overweight subjects. J Dairy Sci. 2020;103:3961-3970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Bellikci-Koyu E, Sarer-Yurekli BP, Karagozlu C, Aydin-Kose F, Ozgen AG, Buyuktuncer Z. Probiotic kefir consumption improves serum apolipoprotein A1 levels in metabolic syndrome patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Nutr Res. 2022;102:59-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Liu JR, Wang SY, Chen MJ, Chen HL, Yueh PY, Lin CW. Hypocholesterolaemic effects of milk-kefir and soyamilk-kefir in cholesterol-fed hamsters. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:939-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Maeda H, Mizumoto H, Suzuki M, Tsuji K. Effects of Kefiran-Feeding on Fecal Cholesterol Excretion, Hepatic Injury and Intestinal Histamine Concentration in Rats. Biosci Microflora. 2005;24:35-40. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Yusuf D, Nuraida L, Dewanti-Hariyadi R, Hunaefi D. In Vitro Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria from Indonesian Kefir Grains as Probiotics with Cholesterol-Lowering Effect. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;30:726-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Ziarno M, Zaręba D, Ścibisz I, Kozłowska M. In Vitro Cholesterol Uptake by the Microflora of Selected Kefir Starter Cultures. Life (Basel). 2024;14:1464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Bourrie BCT, Forgie AJ, Makarowski A, Cotter PD, Richard C, Willing BP. Consumption of kefir made with traditional microorganisms resulted in greater improvements in LDL cholesterol and plasma markers of inflammation in males when compared to a commercial kefir: a randomized pilot study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2023;48:668-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | St-Onge MP, Farnworth ER, Savard T, Chabot D, Mafu A, Jones PJ. Kefir consumption does not alter plasma lipid levels or cholesterol fractional synthesis rates relative to milk in hyperlipidemic men: a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN10820810]. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002;2:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Hadisaputro S, Djokomoeljanto RR, Judiono, Soesatyo MH. The effects of oral plain kefir supplementation on proinflammatory cytokine properties of the hyperglycemia Wistar rats induced by streptozotocin. Acta Med Indones. 2012;44:100-104. [PubMed] |

| 82. | Urdaneta E, Barrenetxe J, Aranguren P, Irigoyen A, Marzo F, Ibáñez FC. Intestinal beneficial effects of kefir-supplemented diet in rats. Nutr Res. 2007;27:653-658. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Punaro GR, Maciel FR, Rodrigues AM, Rogero MM, Bogsan CS, Oliveira MN, Ihara SS, Araujo SR, Sanches TR, Andrade LC, Higa EM. Kefir administration reduced progression of renal injury in STZ-diabetic rats by lowering oxidative stress. Nitric Oxide. 2014;37:53-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Chen HL, Tung YT, Tsai CL, Lai CW, Lai ZL, Tsai HC, Lin YL, Wang CH, Chen CM. Kefir improves fatty liver syndrome by inhibiting the lipogenesis pathway in leptin-deficient ob/ob knockout mice. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38:1172-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Ozcan A, Kaya N, Atakisi O, Karapehlivan M, Atakisi E, Cenesiz S. Effect of Kefir on the Oxidative Stress Due to Lead in Rats. J Appl Anim Res. 2009;35:91-93. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Liu J, Lin Y, Chen M, Chen L, Lin C. Antioxidative Activities of Kefir. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2005;18:567-573. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Güven A, Güven A, Gülmez M. The effect of kefir on the activities of GSH-Px, GST, CAT, GSH and LPO levels in carbon tetrachloride-induced mice tissues. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2003;50:412-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Kanbak G, Uzuner K, Kuşat Ol K, Oğlakçı A, Kartkaya K, Şentürk H. Effect of kefir and low-dose aspirin on arterial blood pressure measurements and renal apoptosis in unhypertensive rats with 4 weeks salt diet. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2014;36:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Brasil GA, Silva-Cutini MA, Moraes FSA, Pereira TMC, Vasquez EC, Lenz D, Bissoli NS, Endringer DC, de Lima EM, Biancardi VC, Maia JF, de Andrade TU. The benefits of soluble non-bacterial fraction of kefir on blood pressure and cardiac hypertrophy in hypertensive rats are mediated by an increase in baroreflex sensitivity and decrease in angiotensin-converting enzyme activity. Nutrition. 2018;51-52:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | de Almeida Silva M, Mowry FE, Peaden SC, Andrade TU, Biancardi VC. Kefir ameliorates hypertension via gut-brain mechanisms in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2020;77:108318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Rodrigues KL, Caputo LR, Carvalho JC, Evangelista J, Schneedorf JM. Antimicrobial and healing activity of kefir and kefiran extract. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;25:404-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Yasar M, Taskin AK, Kaya B, Aydin M, Ozaydin I, Iskender A, Erdem H, Ankatali H, Kandis H. The early anti-inflammatory effect of Kefir in experimental corrosive esophagitis. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84:681-685. [PubMed] |

| 93. | Sugawara T, Furuhashi T, Shibata K, Abe M, Kikuchi K, Arai M, Sakamoto K. Fermented product of rice with Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens induces anti-aging effects and heat stress tolerance in nematodes via DAF-16. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2019;83:1484-1489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Kalamaki MS, Angelidis AS. High-Throughput, Sequence-Based Analysis of the Microbiota of Greek Kefir Grains from Two Geographic Regions. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2020;58:138-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Ding F, Stoyanova LG, Netrusov AI. Microbiomes of Kefir Grains From Regions of Historical Origin and Their Probiotic Potential. Antibiot Chemother. 2022;67:4-7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 96. | Dobson A, O'Sullivan O, Cotter PD, Ross P, Hill C. High-throughput sequence-based analysis of the bacterial composition of kefir and an associated kefir grain. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;320:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Kozyreva II. Species diversity of the microflora of kefir fungi in North Ossetia and the practical use of its representatives. Moscow: Abstract of the dissertation. 2011. Available from: https://static.freereferats.ru/_avtoreferats/01005082179.pdf. |

| 98. | Tsakoeva KM, Dzanagova BV. Identification of the microflora of kefir fungus. Bulletin of scientific works of young scientists, graduate students, undergraduates and students of the Mountain State Agrarian University. 2018; 1: 232-235. Available from: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=37071414. |

| 99. | Gradova NB, Sarantseva AA. Study of the microbial profile of a structured associative culture of microorganisms-kefir fungi. Bulletin of the Samara Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 2012; 5: 704-710. Available from: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=19039760. |

| 100. | Chen HC, Wang SY, Chen MJ. Microbiological study of lactic acid bacteria in kefir grains by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Food Microbiol. 2008;25:492-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Kesmen Z, Kacmaz N. Determination of lactic microflora of kefir grains and kefir beverage by using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. J Food Sci. 2011;76:M276-M283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Blasche S, Kim Y, Mars RAT, Machado D, Maansson M, Kafkia E, Milanese A, Zeller G, Teusink B, Nielsen J, Benes V, Neves R, Sauer U, Patil KR. Metabolic cooperation and spatiotemporal niche partitioning in a kefir microbial community. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6:196-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Marsh AJ, O'Sullivan O, Hill C, Ross RP, Cotter PD. Sequencing-based analysis of the bacterial and fungal composition of kefir grains and milks from multiple sources. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Nalbantoglu U, Cakar A, Dogan H, Abaci N, Ustek D, Sayood K, Can H. Metagenomic analysis of the microbial community in kefir grains. Food Microbiol. 2014;41:42-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Garofalo C, Osimani A, Milanović V, Aquilanti L, De Filippis F, Stellato G, Di Mauro S, Turchetti B, Buzzini P, Ercolini D, Clementi F. Bacteria and yeast microbiota in milk kefir grains from different Italian regions. Food Microbiol. 2015;49:123-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Korsak N, Taminiau B, Leclercq M, Nezer C, Crevecoeur S, Ferauche C, Detry E, Delcenserie V, Daube G. Short communication: Evaluation of the microbiota of kefir samples using metagenetic analysis targeting the 16S and 26S ribosomal DNA fragments. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98:3684-3689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | González-Orozco BD, García-Cano I, Escobar-Zepeda A, Jiménez-Flores R, Álvarez VB. Metagenomic analysis and antibacterial activity of kefir microorganisms. J Food Sci. 2023;88:2933-2949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Leite AM, Mayo B, Rachid CT, Peixoto RS, Silva JT, Paschoalin VM, Delgado S. Assessment of the microbial diversity of Brazilian kefir grains by PCR-DGGE and pyrosequencing analysis. Food Microbiol. 2012;31:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Kazou M, Grafakou A, Tsakalidou E, Georgalaki M. Zooming Into the Microbiota of Home-Made and Industrial Kefir Produced in Greece Using Classical Microbiological and Amplicon-Based Metagenomics Analyses. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:621069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Zhimo VY, Biasi A, Kumar A, Feygenberg O, Salim S, Vero S, Wisniewski M, Droby S. Yeasts and Bacterial Consortia from Kefir Grains Are Effective Biocontrol Agents of Postharvest Diseases of Fruits. Microorganisms. 2020;8:428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Katchieva P, Kharaeva Z, Kirillov M, Ogneva L, Goltsov A, Trofimov D, Rogacheva M, Katchieva Kh, Efimov B, Uzdenov M, Smeianov V. Metagenomics of Autochthonous Kefir Grains Obtained from Mountainous Regions of Karachay-Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria Republics. Lab Diagn East Eur. 2025;14:263-271 Available from: https://recipe-russia.ru/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/YEL_2_2025_Laboratornaya-diagnostika-RF.pdf. |

| 112. | Nejati F, Capitain CC, Krause JL, Kang G, Riedel R, Chang H, Kurreck J, Junne S, Weller P, Neubauer P. Traditional Grain-Based vs. Commercial Milk Kefirs, How Different Are They? Appl Sci. 2022;12:3838. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Dyachkov-Tarasov AN. Anthropologist-ethnographic research as one of the factors in the rise of culture in the national regions of the North Caucasus. Bulletin of the North Caucasus Regional Mountain Research Institute of Local History. 1927. Available from: https://rusneb.ru/catalog/000202_000005_133737/. |

| 114. | Zipaev DV, Rudenko EYu, Zimichev AV. What does kefir grains composition depend on? Dairy industry. 2008; 3: 56-58. Available from: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=13793854. |

| 115. | Metras BN, Holle MJ, Parker VJ, Miller MJ, Swanson KS. Commercial kefir products assessed for label accuracy of microbial composition and density. JDS Commun. 2021;2:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Yegin Z, Yurt MNZ, Tasbasi BB, Acar EE, Altunbas O, Ucak S, Ozalp VC, Sudagidan M. Determination of bacterial community structure of Turkish kefir beverages via metagenomic approach. Int Dairy J. 2022;129:105337. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Yilmaz B, Elibol E, Shangpliang HNJ, Ozogul F, Tamang JP. Microbial Communities in Home-Made and Commercial Kefir and Their Hypoglycemic Properties. Fermentation. 2022;8:590. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Gorbunova LN. Comparison of technological processes for the production of kefir and kefir product. Young scientist. 2017; 9: 48-51. Available from: https://moluch.ru/archive/143/40347/. |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/