Published online Dec 20, 2025. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.108404

Revised: May 22, 2025

Accepted: September 3, 2025

Published online: December 20, 2025

Processing time: 250 Days and 7.9 Hours

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare genetic disorder caused by motile cilia dysfunction. Identifying pathogenic variants is essential for diagnosis and personalized care, especially in consanguineous populations like Saudi Arabia.

This report presents a Saudi pediatric patient diagnosed with PCD who exhibited persistent neonatal tachypnea, chronic productive cough, and recurrent otitis media. Whole-exome sequencing revealed a novel homozygous nonsense variant in the C3orf67 gene (NM_198463.2:c.508C>T), resulting in a truncated, non-functional protein. This mutation likely impairs ciliary motility due to the pro

This case highlights the importance of genetic studies in diagnosing PCD, particularly in communities with a high rate of consanguinity. The identification of a novel homozygous variant in the C3orf67 gene expands the known genetic landscape of the disease. Further research is essential to clarify the functional role of C3orf67 in ciliary biology and its contribution to PCD pathogenesis.

Core Tip: This case report identifies a novel homozygous variant in the C3orf67 gene associated with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) in a Saudi child, expanding the known genetic spectrum of PCD. Through comprehensive clinical evaluation and whole-exome sequencing, this study highlights the importance of genetic testing in early and accurate diagnosis of PCD, particularly in populations with high consanguinity. The findings underscore the need for further research into C3orf67 pathogenic role and reinforce the utility of precision medicine in managing rare ciliopathies.

- Citation: Alkhadidi F, AlSharif H, AlQthami A, Alkhaldi SH, Alsuwat SA, Abosabie SA, Abosabie SA, Kamal NM. Novel homozygous C3orf67 gene variant associated with primary ciliary dyskinesia in a Saudi pediatric patient: A case report. World J Exp Med 2025; 15(4): 108404

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v15/i4/108404.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v15.i4.108404

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a genetically heterogeneous disorder characterized by dysfunction of motile cilia, leading to impaired mucociliary clearance and a range of respiratory manifestations including chronic sinusitis, otitis media, and bronchiectasis[1,2]. The disease often presents in the neonatal period with respiratory distress and may be accompanied by situs inversus and congenital heart defects due to defective ciliary function during embryogenesis[3,4]. Although considered rare, with a global prevalence of approximately 1 in 7500 to 1 in 10000 live births, the incidence may be higher in populations with elevated consanguinity rates, such as those in parts of the Middle East[5-7]. PCD is predominantly inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, though X-linked and autosomal dominant inheritance have also been reported[8]. Advances in molecular diagnostics, particularly whole-exome sequencing, have facilitated the identification of over 50 genes associated with PCD, including dynein axonemal heavy chain 5 (DNAH5), dynein axonemal intermediate chain 1, and radial spoke head 9 homolog (RSPH9), which encode components critical to ciliary structure and motility[5,9,10]. Among Saudi patients, DNAH5 and RSPH9 gene mutations are the most frequently reported; however, the identification of additional genes continues to expand the mutational spectrum and complexity of the disease[6].

The diagnosis of PCD remains challenging due to its phenotypic overlap with other chronic respiratory conditions. As a result, clinical prediction tools such as PCD Rule[11], as well as diagnostic techniques like nasal nitric oxide mea

A 7-year-old Saudi boy was referred to our facility due to recurrent respiratory infections, chronic wet cough, persistent nasal congestion, and recurrent otitis media since infancy.

Symptoms began in the neonatal period with respiratory distress, tachypnea, and wheezing, leading to multiple hospitalizations for suspected pneumonia. Despite multiple courses of antibiotics, symptoms persisted, with frequent episodes of lower respiratory tract infections requiring hospitalization.

At two years of age, the patient was diagnosed with recurrent otitis media and underwent adenotonsillectomy due to persistent infections. However, he continued to experience frequent purulent ear discharge, indicating ineffective mu

| Age (years) | |

| 0 | Respiratory distress noted |

| 2 | Diagnosed with recurrent otitis media, underwent adenotonsillectomy |

| 4 | Exertional dyspnea, chronic cough |

| 7 | High-resolution computed tomography, nasal nitric oxide testing, and whole-exome sequencing performed |

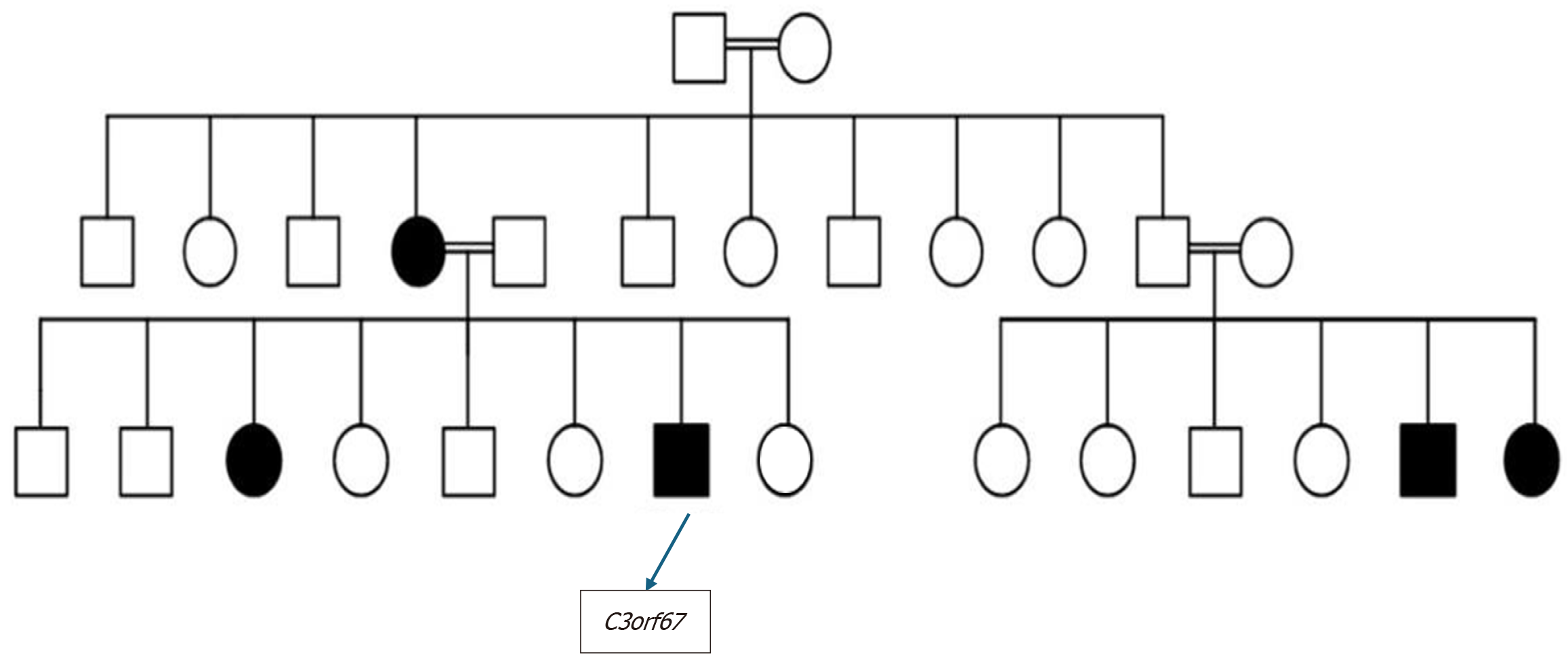

Family history was significant for an older sister diagnosed with PCD at the age of 14. She had a complicated clinical course, including a left lower lobectomy due to recurrent pneumonia and severe bronchiectasis. The patient’s mother had also been diagnosed with bronchiectasis and was under pulmonary investigation. Additionally, his three-year-old younger sister had exhibited persistent neonatal tachypnea and chronic wet cough since birth, raising further suspicion of familial PCD (Figure 1).

Upon examination, the patient appeared well-developed but displayed signs of mild respiratory distress. His weight and height were in the 10th and 25th percentiles, respectively. Chest auscultation revealed scattered crepitations and wheezing, with no digital clubbing or severe respiratory distress. Nasal examination revealed no polyps or mucopurulent discharge. Otoscopic examination indicated signs of chronic otitis media without active infection.

Nasal nitric oxide testing, a crucial screening tool for PCD, showed markedly reduced levels (< 77 NL/minute), further supporting the diagnosis. Whole-exome sequencing (Table 2), confirmed the presence of a homozygous pathogenic variant in C3orf67 (NM_198463.2:c.508C>T), leading to a premature stop codon (p.Arginine170*), resulting in a truncated non-functional protein. This variant has been previously identified in association with PCD but remains under-characterized. According to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics criteria, the C3orf67 variant is classified as likely pathogenic based on population frequency and truncating nature.

| Gene | Variant coordinate | Amino acid change | SNP identifier | Zygosity | In silico parameters | Allele frequencies | Type and classifications |

| C3orf67 | NM_198463.2:c.508C>T | p.Arginine170* | Rs371569928 | Homozygous | PolyPhen: N/A | gnomAD: 0.000016 | Nonsense |

| Align-GVDG: N/A | ESP: -1000 | Likely | |||||

| SIFT: N/A | gnomAD: N/A | Affecting | |||||

| Mutation taste: N/A | CentoMD: N/A | Protein | |||||

| Conservation: Weak | Function | ||||||

| Conservation: Aa | Class 2P1 |

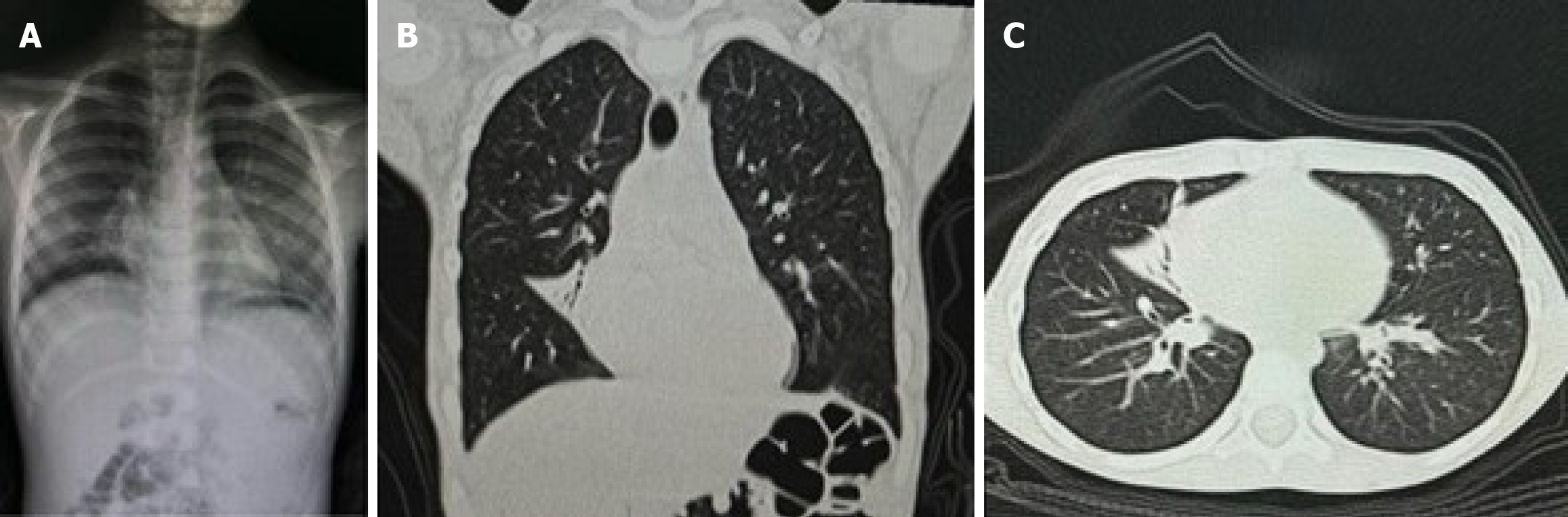

A high-resolution computed tomography scan of the chest showed evidence of early bronchiectasis changes in the right middle lobe, mild atelectasis, and peribranchial thickening (Figure 2). Pulmonary function tests revealed normal forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 second but a reduced mid-expiratory flow (77%), indicating early-stage small airway disease.

The final diagnosis was PCD.

Supportive management to slow disease progression including airway clearance, use of mucolytics, and high-frequency chest wall oscillation. Long-term prophylactic antibiotics with regular follow up of pulmonary function. Bronchodilators are used with airway hyperresponsiveness exacerbations. Family counselling regarding the disease and the genetic testing results.

Currently, the patient is on regular follow up and doing well over the past six months.

PCD is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder affecting ciliary motility, which results in impaired mucociliary clearance and recurrent respiratory infections[1,5]. The clinical spectrum is variable, with patients presenting with neonatal respiratory distress, chronic sinusitis, otitis media, and recurrent pneumonia[2,3,16]. Nearly 50% of affected individuals exhibit situs inversus due to abnormal embryonic left-right axis determination and defective embryonic nodal cilia[1,4,9]. To date, more than 50 pathogenic genes have been implicated in PCD, with mutations affecting dynein arms, radial spokes, and central microtubular structures[5,9,10]. Among Saudi patients, DNAH5 and RSPH9 mutations are the most frequently reported[6], but emerging variants such as C3orf67 suggest additional contributions to disease pathogenesis[7]. The identified mutation in this case (NM_198463.2:c.508C>T) leads to a premature stop codon (p.Arginine170*), predicted to result in a truncated, non-functional protein, thereby impairing normal ciliary structure and motility[10]. The C3orf67 gene, although not fully characterized, is believed to play a structural role in axonemal organization, potentially interacting with radial spoke proteins (UniProt ID: Q8N2E6)[10]. We evaluated the variant as likely pathogenic based on American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics criteria, including its absence from major population databases (gnomAD), truncating nature, and segregation with disease in multiple affected family members[17].

Recent research highlights the critical role of genetic testing in confirming a PCD diagnosis, particularly in consanguineous populations where autosomal recessive inheritance patterns are common[6,7,18]. Advances in genetic technologies, particularly whole-exome and targeted next-generation sequencing, have improved diagnostic accuracy and allowed for the identification of novel variants[5,10,17]. Management of PCD remains largely supportive and aims to prevent disease progression. Standard care includes airway clearance techniques, mucolytics, and high-frequency chest wall oscillation, all of which help improve mucociliary clearance and reduce the frequency of exacerbations[5,13,19]. Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis is frequently employed to suppress chronic infections, and bronchodilators may provide symptomatic relief, especially in patients with airway hyperreactivity[5,13]. Pulmonary function monitoring is essential in tracking disease progression and adjusting treatment[5]. Targeting inflammation has also been proposed as a novel therapeutic approach. Inhaled corticosteroids and leukotriene receptor antagonists have demonstrated some efficacy in reducing airway inflammation and improving respiratory outcomes in selected patients, though their long-term benefit remains under investigation[5,13].

Emerging gene-editing platforms, particularly clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-based systems, hold promise for correcting underlying genetic defects in ciliopathies such as PCD. Although these techniques are in early experimental phases, studies have shown potential for restoring ciliary function in vitro and in animal models[17,20]. However, clinical application faces several hurdles, including safety concerns, high cost, and limited infra

This case highlights the pivotal role of genetic testing in diagnosing PCD and uncovering novel pathogenic variants. The identification of a homozygous C3orf67 variant (NM_198463.2:c.508C>T) expands the known genetic landscape of PCD and underscores the need for further research into its functional impact. Advances in genetic research, precision medicine, and emerging therapies hold promise for improving clinical outcomes and quality of life in individuals with ciliopathies. Future studies should include functional validation of the C3orf67 variant, broader family screenings, and prevalence studies in larger populations.

| 1. | Afzelius BA. A human syndrome caused by immotile cilia. Science. 1976;193:317-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 900] [Cited by in RCA: 831] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 2. | Leigh MW, Ferkol TW, Davis SD, Lee HS, Rosenfeld M, Dell SD, Sagel SD, Milla C, Olivier KN, Sullivan KM, Zariwala MA, Pittman JE, Shapiro AJ, Carson JL, Krischer J, Hazucha MJ, Knowles MR. Clinical Features and Associated Likelihood of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia in Children and Adolescents. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1305-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Guo Z, Chen W, Wang L, Qian L. Clinical and Genetic Spectrum of Children with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia in China. J Pediatr. 2020;225:157-165.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Best S, Shoemark A, Rubbo B, Patel MP, Fassad MR, Dixon M, Rogers AV, Hirst RA, Rutman A, Ollosson S, Jackson CL, Goggin P, Thomas S, Pengelly R, Cullup T, Pissaridou E, Hayward J, Onoufriadis A, O'Callaghan C, Loebinger MR, Wilson R, Chung EM, Kenia P, Doughty VL, Carvalho JS, Lucas JS, Mitchison HM, Hogg C. Risk factors for situs defects and congenital heart disease in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Thorax. 2019;74:203-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Knowles MR, Daniels LA, Davis SD, Zariwala MA, Leigh MW. Primary ciliary dyskinesia. Recent advances in diagnostics, genetics, and characterization of clinical disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:913-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Asseri AA, Shati AA, Asiri IA, Aldosari RH, Al-Amri HA, Alshahrani M, Al-Asmari BG, Alalkami H. Clinical and Genetic Characterization of Patients with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia in Southwest Saudi Arabia: A Cross Sectional Study. Children (Basel). 2023;10:1684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hannah WB, Seifert BA, Truty R, Zariwala MA, Ameel K, Zhao Y, Nykamp K, Gaston B. The global prevalence and ethnic heterogeneity of primary ciliary dyskinesia gene variants: a genetic database analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10:459-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Narayan D, Krishnan SN, Upender M, Ravikumar TS, Mahoney MJ, Dolan TF Jr, Teebi AS, Haddad GG. Unusual inheritance of primary ciliary dyskinesia (Kartagener's syndrome). J Med Genet. 1994;31:493-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zariwala MA, Knowles MR, Omran H. Genetic defects in ciliary structure and function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:423-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zariwala MA, Omran H, Ferkol TW. The emerging genetics of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8:430-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Behan L, Dimitrov BD, Kuehni CE, Hogg C, Carroll M, Evans HJ, Goutaki M, Harris A, Packham S, Walker WT, Lucas JS. PICADAR: a diagnostic predictive tool for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1103-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Corbelli R, Bringolf-Isler B, Amacher A, Sasse B, Spycher M, Hammer J. Nasal nitric oxide measurements to screen children for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Chest. 2004;126:1054-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lucas JS, Paff T, Goggin P, Haarman E. Diagnostic Methods in Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2016;18:8-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lucas JS, Barbato A, Collins SA, Goutaki M, Behan L, Caudri D, Dell S, Eber E, Escudier E, Hirst RA, Hogg C, Jorissen M, Latzin P, Legendre M, Leigh MW, Midulla F, Nielsen KG, Omran H, Papon JF, Pohunek P, Redfern B, Rigau D, Rindlisbacher B, Santamaria F, Shoemark A, Snijders D, Tonia T, Titieni A, Walker WT, Werner C, Bush A, Kuehni CE. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:1601090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 473] [Article Influence: 52.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shapiro AJ, Davis SD, Polineni D, Manion M, Rosenfeld M, Dell SD, Chilvers MA, Ferkol TW, Zariwala MA, Sagel SD, Josephson M, Morgan L, Yilmaz O, Olivier KN, Milla C, Pittman JE, Daniels MLA, Jones MH, Janahi IA, Ware SM, Daniel SJ, Cooper ML, Nogee LM, Anton B, Eastvold T, Ehrne L, Guadagno E, Knowles MR, Leigh MW, Lavergne V; American Thoracic Society Assembly on Pediatrics. Diagnosis of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:e24-e39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 50.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hosie PH, Fitzgerald DA, Jaffe A, Birman CS, Rutland J, Morgan LC. Presentation of primary ciliary dyskinesia in children: 30 years' experience. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:722-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Horani A, Ferkol TW. Advances in the Genetics of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia: Clinical Implications. Chest. 2018;154:645-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee L. Riding the wave of ependymal cilia: genetic susceptibility to hydrocephalus in primary ciliary dyskinesia. J Neurosci Res. 2013;91:1117-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Marthin JK, Petersen N, Skovgaard LT, Nielsen KG. Lung function in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: a cross-sectional and 3-decade longitudinal study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1262-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang C, Svensson RB, Montagna C, Carstensen H, Buhl R, Schoof EM, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP, Yeung CC. Comparison of Tenocyte Populations from the Core and Periphery of Equine Tendons. J Proteome Res. 2020;19:4137-4144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Knowles MR, Zariwala M, Leigh M. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37:449-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/