Published online May 4, 2017. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v6.i2.135

Peer-review started: January 19, 2017

First decision: March 8, 2017

Revised: March 23, 2017

Accepted: April 6, 2017

Article in press: April 8, 2017

Published online: May 4, 2017

Processing time: 103 Days and 8.1 Hours

Thrombotic microangiopathies (TMA) are microvascular occlusive disorders characterized by platelet aggregation and mechanical damage to erythrocytes, clinically characterized by microangiopatic haemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and organ injury. We are reporting a case of a woman patient with severe hemolytic uremic syndrome associated to infectious diarrhoea caused by Shiga toxin-producing pathogen, who were admitted to our intensive care unit. The patient described developed as organ injury, neurological failure and acute renal failure, with need of haemodialysis technique. Due to the severity of the case and the delay in the results of the additional test that help us to the final diagnose, we treated her based on a syndromic approach of TMA with plasma exchange, with favourable clinical evolution with complete recovery of organ failures. We focus on the syndromic approach of these diseases, because thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, one of the disorders that are included in the syndromes of TMA, is considered a haematological urgency given their high mortality without treatment; and also review the TMA in adults: Their pathogenesis, management and outcomes.

Core tip: This case report of an adult patient with thrombotic microangiopathy associated to infectious diarrhoea caused by Shiga toxin-producing pathogen, shows the syndromic approach of thrombotic microangiopathies in adults, with a review of pathogenesis and management of this diseases.

- Citation: Pérez-Cruz FG, Villa-Díaz P, Pintado-Delgado MC, Fernández_Rodríguez ML, Blasco-Martínez A, Pérez-Fernández M. Hemolytic uremic syndrome in adults: A case report. World J Crit Care Med 2017; 6(2): 135-139

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v6/i2/135.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v6.i2.135

Thrombotic microangiopathies (TMA) are microvascular occlusive disorders characterized by platelet aggregation and mechanical damage to erythrocytes[1]. With a low incidence[2], they are characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, with different grades of other organ injury (mainly acute renal failure, neurological and cardiac involvement). Primary TMA syndromes include thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) in their congenital (Upshaw-Schulman syndrome) and acquired varieties, the haemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) associated to infections caused by Shiga toxin-producing pathogens and the atypical HUS, associated to uncontrolled activation of the alternative pathways of complement activation[2]. Secondary TMA are associated to HELLP Syndrome and severe preeclampsia in pregnants, or induced by autoimmune disorders, drugs, systemic infections (HIV, H1N1) and organ transplantations[2].

A 67-year-old woman, with a personal history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia, attended the emergency department for abdominal pain, bleeding diarrhoea and nausea of 3 d of evolution. On examination at emergency arrival, the blood pressure was 95/71 mmHg, the temperature 36.3 °C, the oxygen saturation 92% while breathing ambient air; on physical examination highlighted a diffuse abdominal painful without signs of peritonism.

The laboratory test showed leucocytes count 7.3 × 103 μL, haemoglobin 12.6 g/dL, platelet count 96 × 103 μL; serum creatinine 1.45 mg/dL, serum sodium 132 mmol/L and serum potassium 4.5 mmol/L. She was diagnosed of acute gastroenteritis of probable infectious origin and acute prerenal failure, and treated with fluids, proton pump inhibitor, antiemetics and intravenous antibiotic therapy with ciprofloxacin and metronidazole after sending for culture stool specimens. Despite the established treatment, the patient continued on anuria with unfavourable evolution on blood test (Table 1). A first blood smear showed a non-significant schistocytes count (< 1%).

| Date (d/mo) | 2/10 | 3/10 | 4/10 | 5/10 | 6/10 | 8/10 | 9/10 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 1.45 | 2.02 | 5.19 | 5.82 | 5.19 | 5.24 | 6 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | - | 98 | 132 | 138 | 107 | 115 | 145 |

| LDH (UI/L) | - | - | 1738 | - | 1125 | 803 | - |

| BT (mg/dL) | - | - | - | 2 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Hb (gr/dL) | 12.6 | 12.4 | 12 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 7.5 | 9.1 |

| Platelet (μL) | 96000 | 53000 | 42000 | 59000 | 59000 | 27000 | 21000 |

| Haptoglobine | - | - | - | - | < 6.63 | - | - |

| Blood smear | - | No platelet aggregates, some schistocytes and equinocytes | - | Abundant schistocytes | - | - | - |

| Transfusions | - | - | 1 platelet pool | Plasma exchange | Plasma exchange | Plasma exchange 1 red-cells package | - |

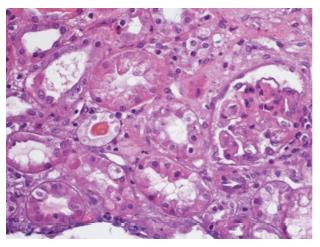

Due to the unfavourable evolution an abdominal CT scan was done, suggestive of proctitis (inflammatory/infectious) and cortical hypoperfusion of both kidneys. At third day she was admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) due to neurological failure with bradipsiquia, anuria and worsen of blood test analysis (Table 1) without hemodynamic instability nor respiratory failure. A blood test analysis for anemia study was done showing haemoglobin 11.2 g/dL, haptoglobin < 6.63 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 1125 U/L, elevated schistocytes count on blood smear and negative direct antiglobulin test, being diagnosed of microangiopathic haemolytic anemia. This along with anuric renal failure and thrombocytopenia (post transfusion platelet count 59 × 103 μL) led to the diagnosis of TMA, and a treatment with urgent plasma exchange and methylprednisolone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day; also the situation of uremia forced to make a first session of haemodialysis. After receiving the result of ADAMTS13 (disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13) test, 24 h later, which were on normal range (55.9%), the daily sessions of plasma exchange were maintained due to the possibility of being severe atypical HUS due to the deterioration of neurological situation and persistence of anuric renal failure; the levels of complement c3 were on low limit of normal range (75 mg/dL). At fourth day of ICU admission the treatment with plasma exchange was discontinued after isolation of verotoxin 2-secreting Escherichia Coli in stool culture. The patient followed a favourable clinical evolution. She presented progressive improvement of neurological symptoms after the third day of ICU admission, being transferred to ward at fifth day of admission. The improvement of renal failure was slower, with recovery of diuresis at second week and needing haemodialysis session until the 23rd day of hospital stay. Renal biopsy (Figure 1) confirmed the diagnosis with histological changes compatible with thrombotic microangiopathic involvement in initial acute phase. At haematological level, the anemia increased at a slow rate, so there were no need of red-cell transfusion until sixth day of hospital stay. Regarding the platelet count, the decrease was more marked requiring platelet transfusion the first day of admission to the ICU to perform invasive techniques.

As shown in the presented case, the delay in the results of the additional tests that help us to the final diagnosis, forces us to carry out a syndromic approach. Given a TMA syndrome it is forced to start the treatment with plasma exchange without delay due to the fact that the delay in initiating the treatment, in case of being a TTP, is known to be correlated with the mortality rate[3]. TTP must be considered a haematological urgency, with a mortality rate near to 90% without an appropriated treatment (50% during the first 24 h) due to ischemic complications (acute cerebrovascular stroke, acute myocardial infarction or cardiac arrhythmias). It is an unusual autoimmune disease (4-6 cases per million per year) characterized by the presence of antibodies directed against ADAMTS13 protein which is involved on Von Willebrand factor (FvW) cleavage. The decrease in plasma activity of such protein results in unusually large FvW multimers and the risk of platelet thrombi in small vessels with high shear rates of red-blood cells; thrombocytopenia is caused by platelet aggregation to form thrombi[3]. Levels of ADAMTS13 lower than 5%- 10% diagnose TTP. Treatment consists in removing ADAMTS13-directed antibodies from circulation by plasma exchange. The most common schedule is the replacement of 1.5 plasma volemia/day until stabilization of clinical parameters, when it is reduced to 1 plasma volemia/d; in cases of vital risk it is possible the replacement of 2 plasma volemia. Plasma exchange can be done with unmodified fresh frozen plasma (FFP), inactivated plasma or cryoprecipitated supernatant[2]. Corticosteroids may be given to patients presumed to have TTP at a dose of prednisone 1 mg/kg per day, 1 to 2 mg/kg of methylprednisolone per day or 1 g of methylprednisolone initially for several days, and tapered once the patient goes into remission. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody to CD20-positive B cells, is recommended in patients who do not respond to or relapse after the combination of plasma exchange and corticosteroids. In our case, treatment began at 4 h after diagnosis at a daily dose of 1.5 plasma volemia and reposition with FFP.

In the reported case, we received the results of ADAMTS13 levels in 24 h allowing us to rule out the diagnosis of TTP. Faced with the possibility of an atypical HUS syndrome due to the persistence of anuria and worsening of neurological symptoms, the treatment with plasma exchange was maintained, and the treatment with eculizumab was also evaluated.

This disorder represents the 5% of all the HUS, so it is considered very uncommon. Usually it is more severe than typical HUS, with neurological or multivisceral involvement in 20% of HUS cases, evolving to chronic renal failure in 50%-80% of cases and with a mortality rate of 10%-15%. It has been demonstrated that 50%-60% of patients carry mutations in genes that control the synthesis of regulatory proteins of complement activation (FHC, PCM, FIC, THBD, FBC y C3) or exhibit immunological disorders with antiFHC antibody development. Anomalous regulation of the alternative pathway of the complement occurs with activation of the coagulation cascade and secondary formation of platelet microthrombi at the level of renal capillaries[2,4]. This fact also explain the characteristics low serum levels of C3 and C4 complement found in this disorder. Unknown environmental factors must co-exist, since 50%-80% of cases of atypical HUS are triggered by infectious processes, mainly gastro-enteric diseases in 30% of cases (including Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli diarrhoea)[5]. Diagnosis of atypical HUS is made by exclusion, being reasonable to initiate a molecular-gene study of the alternative pathway of complement without delaying treatment[5]. Urgent plasma exchange has been during several decades the only efficient treatment available to decrease the morbidity and mortality of atypical HUS, as it infuses regulatory proteins of the normal pathway of complement and eliminates mutant proteins and antiFHC antibodies if they are present. At present, the first line treatment is Eculizumab, an humanized monoclonal IgG2/4 kappa antibody that joints to abnormal protein of C5 complement, blocking its cleavage to C5a and C5b and preventing the generation of the C5b-9 complex of the terminal complement[6]. In our case, this treatment was evaluated, delaying the decision until the arrival of the result of stool culture. After the microbiological confirmation of isolation of verotoxin-producing Escherichia Coli, the definitive diagnosis of typical HUS was reached, stopping treatment with plasma exchange and discouraging treatment with Eculizumab.

Typical HUS is an uncommon disease in adults. It has a relatively good prognosis with a low mortality and with an evolution to chronic renal failure only in 10% of cases; factors of poor prognosis are presence of neurological symptoms and need of renal replacement therapy at the beginning of the disease. Typical HUS is associated to enteric infections by Shiga-toxin bacteria, being the Escherichia coli (serotype O157:H7) the most frequent. Toxin liberation (Shiga-toxin or verotoxin 1 and 2) after ingestion of contaminated foods leads to damage of intestinal mucosa, which explains the characteristic bloody diarrhoea. After penetrating intestinal mucosa, the toxin is transported through the blood to renal tissue damaging endothelium of glomerular capillaries, mesangial cells and tubular cells of kidneys. Endothelium cells damage promotes a prothrombotic state with increase of platelet adhesion and micro-thrombi formation[1,2,7]. Shiga-toxin also induces secretion of abnormal multimers of FvW increasing platelet adhesion. The fact that only 5%-15% of patients who had a gastro-enteric infection develop an HUS indicates that others unknown factors are necessary[2,8]. Treatment remains supportive, the use of antibiotics being controversial since there is an increase of the release of toxin after the death of bacteria leading therefore to an increased risk of developing HUS. In typical HUS plasma exchange has no benefit. The role of Eculizumab is uncertain; although the studies carried out during the 2011 outbreak in Germany did not show benefits[9], there are published short series and isolated cases with good results, always in severe cases[10]. In our case despite the poor prognosis data (neurological involvement and need of haemodialysis technique on the first days) the treatment with that drug was rejected after a favourable evolution and complete recovery of renal function in a short period of four weeks.

A 67-year-old women, with hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia, presented to emergency department with abdominal pain, bleeding diarrhoea and nausea of 3 d of evolution.

The clinical diagnosis of thrombotic microangiopathies (TMA) was based on the presence of thrombocytopenia and the development of acute renal and neurological failure.

Other causes of thrombocytopenia, neurological and acute renal failure as sepsis, and TMA entities.

Thrombocytopenia and anemia, high serum creatinine and lactate dehydrogenase, elevated schistocytes count on blood smear.

In this case report, the authors described the early treatment with plasma exchange.

Due to the low incidence of TMA, although with high mortality in some entities, treatment should be based on syndromic approach according to guidelines.

In patients with TMA, if suspected of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura exist, early treatment with plasma exchange must initiated due to its high mortality rate.

The clinical course had been good writing and the background of the thrombotic microangiopathies had been well reviewed.

| 1. | Moake JL. Thrombotic microangiopathies. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:589-600. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Contreras E, de la Rubia J, Del Río-Garma J, Díaz-Ricart M, García-Gala JM, Lozano M; Grupo Español de Aféresis. [Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines of thrombotic microangiopathies of the Spanish Apheresis Group]. Med Clin (Barc). 2015;144:331.e1-331.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Scully M, Hunt BJ, Benjamin S, Liesner R, Rose P, Peyvandi F, Cheung B, Machin SJ; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and other thrombotic microangiopathies. Br J Haematol. 2012;158:323-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 528] [Cited by in RCA: 571] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Blasco Pelicano M, Rodríguez de Córdoba S, Campistol Plana JM. [Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome]. Med Clin (Barc). 2015;145:438-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Campistol JM, Arias M, Ariceta G, Blasco M, Espinosa L, Espinosa M, Grinyó JM, Macía M, Mendizábal S, Praga M. An update for atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. A consensus document. Nefrologia. 2015;35:421-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ferreira E, Oliveira N, Marques M, Francisco L, Santos A, Carreira A, Campos M. Eculizumab for the treatment of an atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome with mutations in complement factor I and C3. Nefrologia. 2016;36:72-75. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1847-1848. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Kavanagh D, Raman S, Sheerin NS. Management of hemolytic uremic syndrome. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Loos S, Ahlenstiel T, Kranz B, Staude H, Pape L, Härtel C, Vester U, Buchtala L, Benz K, Hoppe B. An outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104: H4 hemolytic uremic syndrome in Germany: presentation and short-term outcome in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:753-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lapeyraque AL, Malina M, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Boppel T, Kirschfink M, Oualha M, Proulx F, Clermont MJ, Le Deist F, Niaudet P. Eculizumab in severe Shiga-toxin-associated HUS. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2561-2563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chang CC, Cid J, Watanabe T S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ