Published online Aug 4, 2014. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v3.i3.68

Revised: June 21, 2014

Accepted: July 25, 2014

Published online: August 4, 2014

Processing time: 164 Days and 22.5 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the performance of the specific French Vittel “Pre-Hospital (PH) resuscitation” criteria in selecting polytrauma patients during the pre-hospital stage and its potential to increase the positive predictive value (PPV) of pre-hospital trauma triage.

METHODS: This was a monocentric prospective cohort study of injured adults transported by emergency medical service to a trauma center. Patients who met any of the field trauma triage criteria were considered “triage positive”. Hospital data was statistically linked to pre-hospital records. The primary outcome of defining a “major trauma patient” was Injury Severity Score (ISS) > 16.

RESULTS: There were a total of 200 injured patients evaluated over a 2 years period who met at least 1 triage criterion. The number of false positives was 64 patients (ISS < 16). The PPV was 68%. The sensitivity and the negative predictive value could not be evaluated in this study since it only included patients with positive Vittel criteria. The criterion of “PH resuscitation” was present for 64 patients (32%), but 10 of them had an ISS < 16. This was statistically significant in correlation with the severity of the trauma in univariate analysis (OR = 7.2; P = 0.005; 95%CI: 1.6-31.6). However, despite this correlation the overall PPV was not significantly increased by the use of the criterion “PH resuscitation” (68% vs 67.8%).

CONCLUSION: The criterion of “pre-hospital resuscitation” was statistically significant with the severity of the trauma, but did not increase the PPV. The use of “pre-hospital resuscitation” criterion could be re-considered if these results are confirmed by larger studies.

Core tip: This is the first evaluation of French Vittel criteria for pre hospital triage of trauma. The results of this study suggest that the criteria are efficient to select the severe trauma patients during the pre-hospital stage [positive predictive value (PPV) of 68%]. The criterion “pre-hospital resuscitation” was significantly correlated with the severity of the trauma, but did not increase the PPV. This criterion, which is the only difference between French and United Stated pH triage criteria, does not procure extra value and compromises potential comparisons with multinational cohort studies. The use of “pre-hospital resuscitation” criterion should be revaluated if these results are confirmed by larger studies.

- Citation: Hornez E, Maurin O, Mayet A, Monchal T, Gonzalez F, Kerebel D. French pre-hospital trauma triage criteria: Does the “pre-hospital resuscitation” criterion provide additional benefit in triage? World J Crit Care Med 2014; 3(3): 68-73

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v3/i3/68.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v3.i3.68

The ideal pre-hospital (PH) triage should optimize the resources in a trauma center or in local hospitals by restricting over- and undertriage scenarios, thereby limiting undue costs and unnecessary geographical constraints for patients and families. Since 1987, a regularly updated PH triage scheme has been prepared by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACSCOT)[1]. This scheme includes mechanism of injuries and replaces previously ineffective scoring such as trauma score[2,3], trauma triage rule[4], CRAM scale[5] and the PH index[6].

French PH trauma triage criteria were developed during the 2002 Emergency Ambulance Service (SAMU) conference in Vittel (France), which addressed French specific PH care[7]. Triage criteria are classified into 5 categories and each of the criteria is sufficient to define a severe trauma, indicating the transfer of the patient to a trauma center. The Vittel criteria are similar to the ACSCOT classification with an additional criterion: “PH resuscitation” which corresponds to the specific management provided by the PH emergency physician (PHEP).

This study aims at evaluating whether the “PH resuscitation” criterion increases the positive predictive value (PPV) of Vittel criteria for an adult population. The study hypothesis is that the PPV is not increased, considering that all of the PH resuscitation maneuvers would be based on vital signs criteria, which are already factored into the triage assessment.

This monocentric study compares the PH Vittel criteria (Table 1) with 2 scores calculated at the end of the clinical assessment: the Injury Severity Score (ISS) and the Trauma Injury Severity Score (TRISS). Polytrauma was defined as an ISS > 16. The goal of the study was to evaluate the performance of Vittel criteria to select polytrauma patients during the pre-hospital stage and evaluate any additional benefit with the use of the specific criterion “PH resuscitation”. The data was prospectively collected. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

| Steps | Severity criteria |

| 1 Vital signs | Glasgow coma scale < 13 or |

| Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or | |

| Saturation O2 < 90% | |

| 2 Evidence of high-energy trauma | Ejection from automobile |

| Death in same passenger compartment | |

| Falls > 6 m | |

| Victim thrown or crushed | |

| Global assessment of the trauma (aspect of the crashed vehicle, vehicle telemetry data consistent with high risk of injury, no motorcycle helmet, no seat belt) | |

| Blast | |

| 3 Anatomy of injury | Penetrating trauma of head, neck thorax, abdomen, pelvis, thigh, and arm |

| Flail chest | |

| Severe burns, smoke inhalation | |

| Pelvic bone fracture | |

| Suspicion of medullar trauma | |

| Amputation proximal to wrist or ankle | |

| Acute ischemia of the limb | |

| 4 Pre-hospital resuscitation | Intubated and mechanically ventilated patients |

| IV Fluids > 1000 mL (colloids) | |

| Catecholamine | |

| Anti-shock trousers inflated | |

| 5 Special patient or system considerations | Age > 65 yr |

| Heart failure | |

| Respiratory failure | |

| Pregnancy > 12 wk |

From December 2008 to January 2010, all trauma patients were evaluated by the emergency physician in the field. The number of positive Vittel criteria was determined from the trauma case history including the phone report to the emergency department (ED). Patients presenting with one positive Vittel criterion were transported to and managed in a well equipped trauma center with an emergency department, intensive care unit, interventional radiology, a burn unit, and multiple surgical specialties (digestive, orthopedics, urology, otorhinolaryngology, plastic/reconstructive, neurosurgery). The facility receives an annual patient population of 900000, primarily tourists as well as residents of suburban and rural neighborhoods.

The pre-defined data sheet utilized was divided into 2 parts: (1) collected PH stage data: Glasgow coma scale, respiratory rate, blood pressure, heart rate, injury mechanism, time of management, Vittel criteria, resuscitation protocol (IV fluids, oral intubation, venous access, drugs); (2) collected ED data: vitals, resuscitation protocol, injury profile, surgery, interventional radiology, survey, cause of death. ISS and TRISS were calculated at patient discharge.

A statistical analysis evaluated the performance of the Vittel criteria in selecting patients with an ISS > 16 (Stata version 9 software, Stata Corporation). A descriptive analysis with the comparison between the subgroups was made with ANOVA. The correlation between the variables utilized the Pearson coefficient. Linear regression, univariate and multivariate analysis were used to measure the link between Vittel criteria and the ISS and TRISS. The significance level of the study was III.

Two hundred trauma patients (using Vittel criteria) were included. Characteristics and profiles of injuries are described in Table 2. The median age was 40.4 years (with range of 16-96 years) and 78.5% of patients were male. All traumas were high energy (road trauma 71%, serious falls 15%). The median values of ISS and TRISS were respectively 22 (1-75, EC = 16.1) and 95.8% (2-99, EC = 29). As expected, the 2 scores had a high inverse correlation (ρ = -0.77). Forty-four percent of patients were hemodynamically unstable, 48.5% had limb trauma, head trauma 48.5%, and thoracic trauma 44.5%. The most common injury involved trauma of the extremities (48.5%), then head trauma (48.5%), and thoracic trauma (44.5%). The severity of trauma did not vary with gender. The elderly patients had a lower TRISS (P = 0.002) but with an unchanged ISS (P = 0.118). No mechanism was associated with a high ISS. Gunshot-penetrating trauma could be associated with a lower TRISS (P = 0.06).

| Mechanism | n (%) | |

| Motorcycle crash | 105 (52.7) | |

| Car crash | 37 (18.5) | |

| Fall | 30 (15.8) | |

| Pedestrian vs auto | 16 (8) | |

| Gunshot wound | 5 (2.5) | |

| Stab wound | 2 (1) | |

| Other | 4 (2) | |

| Anatomy of injury | ||

| Total n (%) | Hemorragic group n (%) | |

| Number | 200 | 33 (16.5) |

| Extremity | ||

| Upper | 60 (30) | 8 (24) |

| Lower | 53 (26.5) | 9 (28) |

| Thorax | ||

| Lung trauma | 39 (19.5) | 3 (9) |

| Pneumothorax | 29 (14.5) | 4 (12) |

| Hemothorax | 21 (10.5) | 14 (42.5) |

| Head | 97 (48.5) | 14 (42.5) |

| Face | 39 (19.5) | 4 (12) |

| Spine | ||

| Stable | 29 (14.5) | 4 (12) |

| Unstable | 8 (4) | 0 |

| Pelvic bone | ||

| Stable | 26 (13) | 4 (12) |

| Unstable | 10 (5) | 6 (18) |

| Abdomen | ||

| Hemoperitoneum | 31 (15.5) | 17 (51.5) |

| Hemoretroperitoneum | 13 (6.5) | 6 (18) |

| Pneumoperitoneum | 3 (1.5) | 1 (3) |

| Other | 3 (1.5) | 1 (3) |

All patients were managed by a PHEP on the field. The median PH duration was 64.9 min (DS = 41.7 min, 15-240). This duration was associated with a lower TRISS (P = 0.015) but not with a higher ISS (P = 0.075). The first PHEP clinical report by phone and the first ED categorization of the patient were highly correlated (P = 0.88).

The number of false positives was 64 patients (ISS < 16 and at least one positive Vittel criteria). The PPV was 68%. The PPV was not significantly increased with the use of the criterion “PH resuscitation” (68% vs 67.8%). The sensitivity and the negative predictive value could not be evaluated in this study since it only included patients with positive Vittel criteria.

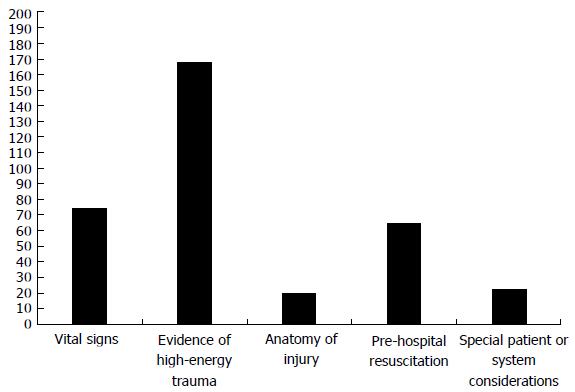

The distribution of the Vittel criteria is depicted in Figure 1. The most frequent criteria were “high energy trauma” (84.5%), and “physiological variables” (37%). Forty-eight percent of the patients had only one positive criterion; 23%, 23.5% and 3% had respectively 2, 3 and 4 positive criteria. No patient had 5 positive criteria.

The correlation between the positive Vittel criteria and the severity is detailed in Table 3. In univariate analysis, 3 criteria were associated with severity: “Vital signs” (OR = 2.8; P = 0.002; 95%CI: 1.4-5.3), “PH resuscitation” (OR = 7.2; P = 0.005; 95%CI: 1.6-31.6), and “Special patient or system consideration” (OR = 7.2; P = 0.009; OR = 1.6-31.6). In multivariate analysis, 2 criteria were associated with the severity: “vital signs” (OR = 2.4; P = 0.04; 95%CI: 1.0-5.7) and “Special patient or system consideration” (OR = 9.2; P = 0.004; 95%CI: 2.0-41.9). For the entire cohort: The more a patient had positive criteria, the more severe the trauma (P < 0.0001) and the more the patient needed emergency surgery (not statistically significant). For the group of “hemorrhagic patients”: the more a patient had positive criteria, the more severe the trauma (not statistically significant) and the more the patient needed an emergency surgery (significant with regression analysis).

| Vittel Criteria | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| OR | P | 95%CI | OR | P | 95%CI | |

| Vital signs | 2.8 | 0.002 | 1.4-5.3 | 2.4 | 0.04 | 1.0-5.7 |

| Evidence of high-energy trauma | 1 | 0.8 | 0.5- 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.64 | 0.5-3.1 |

| Anatomy of injury | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2-1.4 | 0.5 | 0.21 | 0.2-1.5 |

| Pre-hospital resuscitation | 2.6 | 0.005 | 1.3-5.0 | 1.8 | 0.18 | 0.7-4.4 |

| Special patient or system considerations | 7.2 | 0.009 | 1.6-31.6 | 9.2 | 0.004 | 2.0-41.9 |

This study was intended to evaluate if the “PH resuscitation” criterion increases the PPV of Vittel criteria for an adult population. The study hypothesis was that the PPV is not increased, considering that all of the PH resuscitation maneuvers would presumably be based on vital sign criteria, which would then already be factored into the triage assessment. The results suggest that the French Vittel criteria are effective in selecting polytrauma patients (ISS > 16) with a PPV of 68%. The criterion of “PH resuscitation” does not improve the performance of the Vittel criteria.

There is no consensus for the definition of polytrauma; many definitions have been used: ISS > 16[8-12], ISS > 20[13], ISS > 16 associated with hospital length[14], ISS associated with resources used[8,15,16]. Other studies define polytrauma depending on the resources used[4,17-20]. In this study we used the definition of the ACSCOT (ISS > 16). This definition optimizes the cost/efficiency ratio of the trauma centers[21].

In Westernized countries, severe trauma patients are usually identified during the PH stage by triage criteria as the “ACSCOT field triage decision scheme”, the last version published in 2006. Many studies have since been published to evaluate the triage criteria, with varying results[8,21-25]. In 2011, Newgard et al[23] published a major study about pre-hospital triage. In the study, 122345 patients were included and 7100 (5.8%) had an ISS > 16. The pre-hospital triage was done by the paramedics using the ACSCOT scheme. The sensitivity was 85% for all patients and 79% for patients over 55 years of age. The specificity was 68.7% for all the patients and 75.4% for patients older than 55 years. The PPV to identify major trauma patients was 71.1%.

In France, the PH management of a trauma patient is performed by a mobile team including a PHEP. PHEP field management includes Cardio Pulmonary resuscitation with oral intubation, PRBC transfusion, chest tube, central venous access, and/or Fast Assessment Sonogram for Trauma exam. Therefore, specific criteria for pre-hospital triage have been published in 2002 during the SAMU conference in Vittel[7] and are summarized in table 1. These are very similar to those of the ACSCOT, but also include the additional criterion of “PH resuscitation”. As expected, the performance of the Vittel criteria to identify polytrauma is very similar to the ACSCOT score (PPV: 68% vs 71.1%).

In this study, the criterion “PH resuscitation” was met by 64 patients (32%) but 10 of them had an ISS < 16. The false positive rate was 15%. This was significantly correlated with the severity of the trauma in univariate analysis (OR = 7.2; P = 0.005; 95%CI: 1.6-31.6). However, despite this correlation, the overall PPV was not significantly increased by the use of the criterion “PH resuscitation” (68% vs 67.8%)

Criterion “Vital signs”: In this study, the criterion “Vital signs” was significantly associated with the severity of the trauma in univariate analysis (OR = 2.8; P = 0.002; 95%CI: 1.4-5.3) and multivariate analysis (OR = 2.4; P = 0.04; 95%CI: 1.0-5.7). The effectiveness of this criterion was already discovered by Wuerz et al[24], in 1996, with a low sensitivity (56%) but a high specificity (86%). This was associated with 20% mortality rate in the study published in 2005 by Hannan et al[26].

Criterion “evidence of high-energy trauma”: In this study, the criterion “evidence of high-energy trauma” was not correlated with the severity of the trauma in the univariate or multivariate analysis. Many studies have already shown that the mechanism of trauma is not associated with the severity of trauma[10,13,27,28]. In a study published in 1986, Lowe et al [27] found an overtriage rate ranging from 14% to 43% in a cohort of 631 patients. This trend was corroborated in 2003 by Santaniello et al[28]. In a series of 830 patients, only 50% of the patients sorted by this criterion required surgery or an ICU admission. This criterion presents an element of sensitivity for the PH triage.

Criterion “anatomy of injury”: In this study, the criterion ‘anatomy of injury’ was not correlated with the severity of the trauma. Few studies have specifically analyzed this criterion: in 1995 Cooper et al[8] found a sensitivity of 40% with a PPV of 22%.

Criterion “Special patient or system considerations”: Within the study the criterion “Special patient or system considerations” was significantly associated with the severity of the trauma in univariate analysis (OR = 7.2; P = 0.009; 95%CI: 1.6-31.6) and multivariate analysis (OR = 9.2; P = 0.004; 95%CI: 2.0-41.9), but an accurate analysis of this criterion is difficult due to its variability (its contents being extremely PHEP dependent). It is however interesting to notice, that the specificity of the triage was higher for the patient older than 55 years (75.4% vs 64.3%) in the study of the ACSCOT[23].

The limitations of this study include a lack of statistical power due to the small cohort size. Also, we only included patients with one or more positive Vittel criteria, therefore we could not adequately assess the sensitivity of the criteria, which is the largest limitation. In addition, while the number of positive criteria was significantly associated with the severity of the trauma, this relationship did not exist with the subgroup “hemorrhagic patients” despite a hemorrhagic lesion being a severity factor in trauma, as shown by the higher need of emergency surgery. This paradox is probably due to a lack of statistical power due to the small cohort of hemorrhagic patients (n = 33). A larger study size is needed.

Overall, the results of this study indicate that the French Vittel criteria are efficient in selecting severe trauma patients during the pre-hospital stage, with a PPV of 68%. The criterion “pre-hospital resuscitation” was significantly correlated with the severity of the trauma, but did not increase the PPV. This criterion, which is the only difference between the French and the United States PH triage criteria, does not provide any added benefit, and actually compromises potential comparisons with multinational cohort studies. The use of “pre-hospital resuscitation” criterion should be re-evaluated if these results are confirmed by larger studies.

A pre-hospital (PH) triage is performed to optimize the resources in a trauma center or in local hospitals by restricting over- and undertriage scenarios. Since 1987, a regularly updated PH triage scheme has been prepared by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACSCOT). This scheme includes mechanism of injuries. French PH trauma triage criteria were developed in 2002. They are similar to the ACSCOT classification with an additional criterion: “PH resuscitation” which corresponds to the specific management provided by the PH emergency physician.

This article is the first evaluation of the French triage criteria. They are no related or similar studies. A larger study will be performed by the emergency health service in Paris in 2015.

The results of this study indicate that the French Vittel criteria are efficient in selecting severe trauma patients during the pre-hospital stage, with a PPV of 68% but the criterion “pre-hospital resuscitation” did not increase the PPV. This criterion does not provide any added benefit, and actually compromises potential comparisons with multinational studies. This study is a clear advocacy for reconsidering the use this criterion if these results are confirmed by larger studies.

The authors performed a monocentric prospective cohort study of injured adults to evaluate the performance of the French Vittel criteria to select polytrauma patients during pre-hospital stage and evaluate if their pre hospital resuscitation criterion increases positive predictive value of pre-hospital trauma triage.

| 1. | Hospital and prehospital resources for optimal care of the injured patient. Committee on Trauma of the American College of Surgeons. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1986;71:4-23. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Gennarelli TA, Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Copes WS, Alves WM. Mortality of patients with head injury and extracranial injury treated in trauma centers. J Trauma. 1989;29:1193-1201; discussion 1201-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Moreau M, Gainer PS, Champion H, Sacco WJ. Application of the trauma score in the prehospital setting. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:1049-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Baxt WG, Jones G, Fortlage D. The trauma triage rule: a new, resource-based approach to the prehospital identification of major trauma victims. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:1401-1406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gormican SP. CRAMS scale: field triage of trauma victims. Ann Emerg Med. 1982;11:132-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Koehler JJ, Baer LJ, Malafa SA, Meindertsma MS, Navitskas NR, Huizenga JE. Prehospital Index: a scoring system for field triage of trauma victims. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:178-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Riou B, Thicoïpé M, Atain-Kouadio P, Carli P. Comment évaluer la gravité ? In : Samu de France. Actualités en réanimation préhopistalière : le traumatisé grave. Paris: SFEM éditions 2002; 115-118. |

| 8. | Cooper ME, Yarbrough DR, Zone-Smith L, Byrne TK, Norcross ED. Application of field triage guidelines by pre-hospital personnel: is mechanism of injury a valid guideline for patient triage? Am Surg. 1995;61:363-367. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Esposito TJ, Offner PJ, Jurkovich GJ, Griffith J, Maier RV. Do prehospital trauma center triage criteria identify major trauma victims? Arch Surg. 1995;130:171-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Knopp R, Yanagi A, Kallsen G, Geide A, Doehring L. Mechanism of injury and anatomic injury as criteria for prehospital trauma triage. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:895-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Long WB, Bachulis BL, Hynes GD. Accuracy and relationship of mechanisms of injury, trauma score, and injury severity score in identifying major trauma. Am J Surg. 1986;151:581-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bond RJ, Kortbeek JB, Preshaw RM. Field trauma triage: combining mechanism of injury with the prehospital index for an improved trauma triage tool. J Trauma. 1997;43:283-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cottington EM, Young JC, Shufflebarger CM, Kyes F, Peterson FV, Diamond DL. The utility of physiological status, injury site, and injury mechanism in identifying patients with major trauma. J Trauma. 1988;28:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | West JG, Murdock MA, Baldwin LC, Whalen E. A method for evaluating field triage criteria. J Trauma. 1986;26:655-659. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Newgard CD, Hui SH, Griffin A, Wuerstle M, Pratt F, Lewis RJ. Prospective validation of an out-of-hospital decision rule to identify seriously injured children involved in motor vehicle crashes. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:679-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Simon BJ, Legere P, Emhoff T, Fiallo VM, Garb J. Vehicular trauma triage by mechanism: avoidance of the unproductive evaluation. J Trauma. 1994;37:645-649. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Henry MC, Hollander JE, Alicandro JM, Cassara G, O’Malley S, Thode HC. Incremental benefit of individual American College of Surgeons trauma triage criteria. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:992-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zechnich AD, Hedges JR, Spackman K, Jui J, Mullins RJ. Applying the trauma triage rule to blunt trauma patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:1043-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Phillips JA, Buchman TG. Optimizing prehospital triage criteria for trauma team alerts. J Trauma. 1993;34:127-132. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Engum SA, Mitchell MK, Scherer LR, Gomez G, Jacobson L, Solotkin K, Grosfeld JL. Prehospital triage in the injured pediatric patient. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:82-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | MacKenzie EJ, Weir S, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Wang W, Scharfstein DO, Salkever DS. The value of trauma center care. J Trauma. 2010;69:1-10. [PubMed] |

| 22. | van Laarhoven JJ, Lansink KW, van Heijl M, Lichtveld RA, Leenen LP. Accuracy of the field triage protocol in selecting severely injured patients after high energy trauma. Injury. 2014;45:869-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Newgard CD, Zive D, Holmes JF, Bulger EM, Staudenmayer K, Liao M, Rea T, Hsia RY, Wang NE, Fleischman R. A multisite assessment of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma field triage decision scheme for identifying seriously injured children and adults. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:709-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wuerz R, Taylor J, Smith JS. Accuracy of trauma triage in patients transported by helicopter. Air Med J. 1996;15:168-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Báez AA, Lane PL, Sorondo B. System compliance with out-of-hospital trauma triage criteria. J Trauma. 2003;54:344-351. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Hannan EL, Farrell LS, Cooper A, Henry M, Simon B, Simon R. Physiologic trauma triage criteria in adult trauma patients: are they effective in saving lives by transporting patients to trauma centers? J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:584-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lowe DK, Oh GR, Neely KW, Peterson CG. Evaluation of injury mechanism as a criterion in trauma triage. Am J Surg. 1986;152:6-10. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Santaniello JM, Esposito TJ, Luchette FA, Atkian DK, Davis KA, Gamelli RL. Mechanism of injury does not predict acuity or level of service need: field triage criteria revisited. Surgery. 2003;134:698-703; discussion 703-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Moghazy A, Sadoghi P S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL