Published online Dec 9, 2024. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v13.i4.97399

Revised: August 17, 2024

Accepted: August 23, 2024

Published online: December 9, 2024

Processing time: 154 Days and 23.7 Hours

Seizures are one of the most common neurological complications encountered in the intensive care unit (ICU). They can occur in the background of exacerbation of a known neurological disease or secondary to non-neurological conditions such as sepsis and metabolic disturbances. However, there is a paucity of literature on the incidence and pattern of new-onset seizures in ICUs.

To study the incidence and patterns of new-onset seizures in patients admitted to the medical ICU.

This was a prospective, multicenter, observational study performed in two tertiary care centers in Hyderabad, India over a period of 1 year. Patients upon ICU admission, who developed new-onset generalized tonic clonic seizures (GTCS), were enrolled. Those with a pre-existing seizure disorder, acute cerebrovascular accident, head injury, known structural brain lesions, or chronic liver disease were excluded as they have a higher likelihood of developing seizures. All enrolled patients were subjected to biochemical routines, radiological imaging of either computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, and other relevant laboratory tests as per clinical suspicion according to the protocol, and their data were recorded. Statistical analyses were conducted using descriptive statistics, χ2 tests, and linear regression.

A total of 61 of 2522 patients developed GTCS. Among all etiologies of seizures, metabolic causes were most frequent (35%) followed by infective causes (27%) and others (new-onset structural, drug withdrawal, drug-induced, toxicology-related, and miscellaneous factors). Logistic regression analysis showed that increased sodium and calcium levels were associated with a lower likelihood of developing seizures.

This study identified the etiology of new-onset seizures developing in critically ill patients admitted to the ICU. These findings highlight the need for targeted monitoring of those at risk of developing seizures.

Core Tip: Seizures can occur in critically ill patients due to neurological and non-neurological causes and are associated with high morbidity and mortality. This was a multicenter observational study on the incidence and etiology of new-onset seizures in patients admitted to the medical intensive care unit who did not have any known predisposing factors for developing seizures. We found that metabolic derangement-related seizures were the most common followed by tropical infections and other causes. These findings highlight the need for the targeted monitoring and timely evaluation of those at risk of developing seizures.

- Citation: Perveen S, Srinivasan A, Prusty BSK, Jyotsna CV, Pabba S, Reddy R, Sheshala K, Ragavendra Asranna K. In-hospital new-onset seizures in patients admitted to the medical intensive care unit: An observational study and algorithmic approach. World J Crit Care Med 2024; 13(4): 97399

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v13/i4/97399.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v13.i4.97399

Encountering complications that involve the central and peripheral nervous systems is not a rarity in critically ill patients and adds to morbidity and mortality[1]. Seizures are one of the most common neurological complications that occur in intensive care units (ICUs). The incidence of seizures in ICUs varies based on the underlying diagnosis and is reported to be 3.3%-34%[2]. Seizures can occur in the background of exacerbation of a known seizure disorder. They can also occur secondary to a non-neurological cause for which a patient has been admitted such as infections, metabolic disturbances, drug-induced or drug withdrawals or secondary to any new-onset complication such as intracerebral bleed secondary to thrombocytopenia in the ICU[1]. Evaluating the cause of new-onset seizure and timely addressal of the same paves the way in preventing further recurrence. Moreover, it also aids in improving in-hospital morbidity and mortality. Although there is a paucity of literature available on the pattern of new-onset seizures, studies do not rule out patients who already have a predisposition to seizures[3,4].

In the present observational study, we identified the incidence and different etiologies of new-onset seizures.

The present study was conducted in the medical ICU of two tertiary care centers in the Department of Critical Care Medicine, Virinchi Hospital (Hyderabad, India) and Yashoda Hospital, Malakpet (Hyderabad, India). Approval from the Scientific Research Committee of Virinchi Hospital was taken prior to patient enrollment. As this was an observational study involving no risks as part of the study protocol, consent was waived upon approval. We followed the STreng

As per the admission record of the medical ICU in the Department of Critical Care Medicine at Virinchi Hospital and Yashoda Hospital, Malakpet, 2522 adult patients of either sex were admitted, of whom 61 patients with witnessed seizures were enrolled in our study upon satisfying the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Adult patients above 18 years of age who developed new-onset generalized tonic clonic seizures (GTCS) during their stay in the ICU for various reasons.

Pre-existing seizure disorder; acute cerebrovascular accident; head injury; known structural brain lesions; chronic liver disease.

This was a multicenter, prospective, observational study conducted for a period of 1 year between April 2023 and March 2024 in two tertiary care hospitals in Hyderabad, India.

All patients with new-onset seizures were interrogated for any addictions, co-morbidities, or any other predisposing factor for developing seizures and were subjected to biochemical routine labs, radiological imaging of either computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, lumbar puncture if indicated, and other relevant laboratory tests as per clinical suspicion. The remaining patient management was done by the investigator(s).

Continuous variables are reported as the means with standard deviations. Associations were calculated as the odds ratios with 95% confidence interval (CI). Mann-Whitney U tests, Student's t tests, or χ2 tests were used as appropriate and correlated with patient characteristics. The binomial association between single estimations and risk of seizures and mortality along with the association of cumulative estimations and hospital mortality were explored using binomial logistic regression analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States).

A total of 2522 patients were admitted to medical ICUs between April 2023 and March 2024 across two tertiary care hospitals in Hyderabad, India. Upon excluding those patients who did not fulfil our inclusion criteria, 61 adult patients were enrolled for our observational study. Demographics, baseline characteristics, and mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score are outlined in Table 1.

| Admission characteristics | n of 61/2522 | Percentage |

| Age in yr | ||

| 18-30 | 11 | 18.03 |

| 31-50 | 30 | 49.18 |

| 51-70 | 20 | 32.78 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 33 | 54.09 |

| Male | 28 | 45.90 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 | 37.70 |

| Hypertension | 21 | 34.42 |

| Coronary artery disease | 12 | 19.67 |

| Hypothyroidism | 7 | 11.47 |

| Mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score | 11.48 | |

| No. of patients who died | 15 | 24.59 |

The demographic profile among the study population was equally distributed and patients had a mean age of 43 years. Diabetes mellitus was the most common comorbid condition in patients admitted to the ICU. The etiological data of new onset-seizures in the ICU are outlined in Table 2.

| Etiology | Total, n | Mortality, n |

| Metabolic | 21 | |

| Hyponatremia | 14 | 2 |

| Hypocalcemia | 3 | 1 |

| Uremia | 3 | 0 |

| Hypoglycemia | 1 | 0 |

| Structural | 5 | |

| Intracerebral bleed | 2 | 2 |

| Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome | 3 | 0 |

| Infective | 17 | |

| Dengue | 8 | 2 |

| Leptospirosis | 2 | 0 |

| Scrub typhus | 3 | 1 |

| Septic encephalopathy | 1 | 0 |

| Viral encephalitis | 3 | 1 |

| Bacterial meningitis | 1 | 1 |

| Drug withdrawal | 2 | 0 |

| Drug-related | 4 | 4 |

| Toxicology | 5 | |

| Organophosphorous poisoning | 3 | 0 |

| Herbicide poisoning | 1 | 0 |

| Benzodiazepine overdose | 1 | 0 |

| Others | 4 | |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | 3 | 1 |

| Somatoform disorder | 1 | 0 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 |

Metabolic abnormalities were the leading cause of new-onset seizures in our study population (34.42%), followed by infective etiology with tropical fever being most prevalent. We could get to see two cases of withdrawal seizures with both of them admitted with various etiologies had their index seizure episode secondary to alcohol withdrawal. By way of reducing seizure threshold, two patients receiving imipenam-cilastatin and two patients receiving piperacillin-tazobactum witnessed seizures. All of them had grave outcome probably attributed to the severity of underlying illness.

Though rest of the etiological factors stand as a manifestation of underlying disease and its pathophysiological process, metabolic abnormalities and related seizures is one subset that can be kept under close watch to prevent occurrence of seizures.

Logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of sodium and calcium levels on the likelihood that patients develop seizures. The model explained 26.3% of the variance in seizures and correctly classified 63.3% of the cases. Increasing sodium levels and calcium was associated with a reduction in the likelihood of exhibiting seizures. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, P < 0.05 (Table 3).

| Parameter | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Sodium | 0.013 | 0.922 | 0.865 | 0.983 |

| Calcium | 0.005 | 0.109 | 0.023 | 0.520 |

We did perform logistic regression analysis for prediction of death using metabolic and other parameters and we could see none of them predicted mortality (Table 4).

| Parameter | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Sodium | 0.051 | 1.101 | 1.000 | 1.212 |

| Potassium | 0.424 | 0.590 | 0.161 | 2.153 |

| Calcium | 0.764 | 1.415 | 0.146 | 13.716 |

| Creatinine | 0.668 | 1.059 | 0.816 | 1.374 |

| Blood sugars | 0.292 | 1.012 | 0.990 | 1.035 |

| Length of stay in ICU | 0.510 | 1.159 | 0.747 | 1.799 |

Seizures in the setting of critical illness are often multifactorial and require complex diagnostic and management strategy. Delay in the recognition of seizures lead to an increase in mortality. The etiology of new-onset of seizures in the ICU vary depending on the patient population, underlying disease, and region.

In our study the incidence of new onset GTCS in our study was 2.41%, which is very similar to a study by Pannem et al[3], which showed a GTCS incidence of 2.4% where those patients with cerebrovascular accident, structural brain lesions, were included. In a study by Wagner et al[4], the incidence of new onset seizures in ICU was 0.8%, which included both generalized and focal seizures. Hence, the incidence of new-onset seizures is highly variable and depends upon the underlying clinical condition and geography.

With the increased burden of diabetes in our country, diabetes mellitus was the most common comorbidity followed by hypertension in our study. Among the metabolic causes, hyponatremia was the most common followed by hypocalcemia and uremia. Hyponatremia is a common metabolic abnormality seen in critically ill patients attributed to multifactorial etiology[6], and may be associated with a poor outcome in certain subset of critically ill patients. In those cases, we suggest serial monitoring of serum sodium levels and treatment of hyponatremia. Although asymptomatic, targeting the normal range should be done to prevent seizures, as substantiated by our logistic regression analysis, as well to improve outcomes. Similar to hyponatremia, hypocalcemia is also associated with poor outcomes, but may be a marker rather than a direct cause of disease severity. Although statistically significant, decreases in calcium levels are associated with an increased incidence of seizures, and aiming for a normal range of calcium levels in asymptomatic hypocalcemic patients has conflicting evidence; thus, further studies are warranted[7].

Two patients developed intracerebral bleed and both of them had underlying thrombocytopenia. Three patients had posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) secondary to underlying eclampsia in one case and hypertensive crisis in two cases. The triggers for PRES include hypertension, preeclampsia, renal failure, liver failure, exposure to cytotoxic medications or immunosuppressants, autoimmune disorders such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus or sepsis. Prompt vigilance and awareness are required to identify the etiology, as failure to treat early leads to worse outcomes[8].

Among the infective causes of seizures, tropical fever related-encephalopathy[9] was at the top of the list in our study cohort, comprising 82% of cases, followed by viral encephalitis and bacterial meningitis. Few other Indian studies have reported similar findings. These results warrant close monitoring of patients admitted to the ICU with high clinical suspicion of developing seizures.

The norm that sicker patients get admitted to the ICU for various reasons may be related to the downfall effects of antibiotics. Four of our patients developed seizures as an adverse reaction to antibiotics, two of them received imipenam-cilastatin, and two patients received piperacillin-tazobactum. From the literature, common antibiotics causing seizures are beta lactams, fluroquinolones, and antitubercular agents such as isoniazid. These drugs predispose to seizures by decreasing GABA-mediated mechanisms[10].

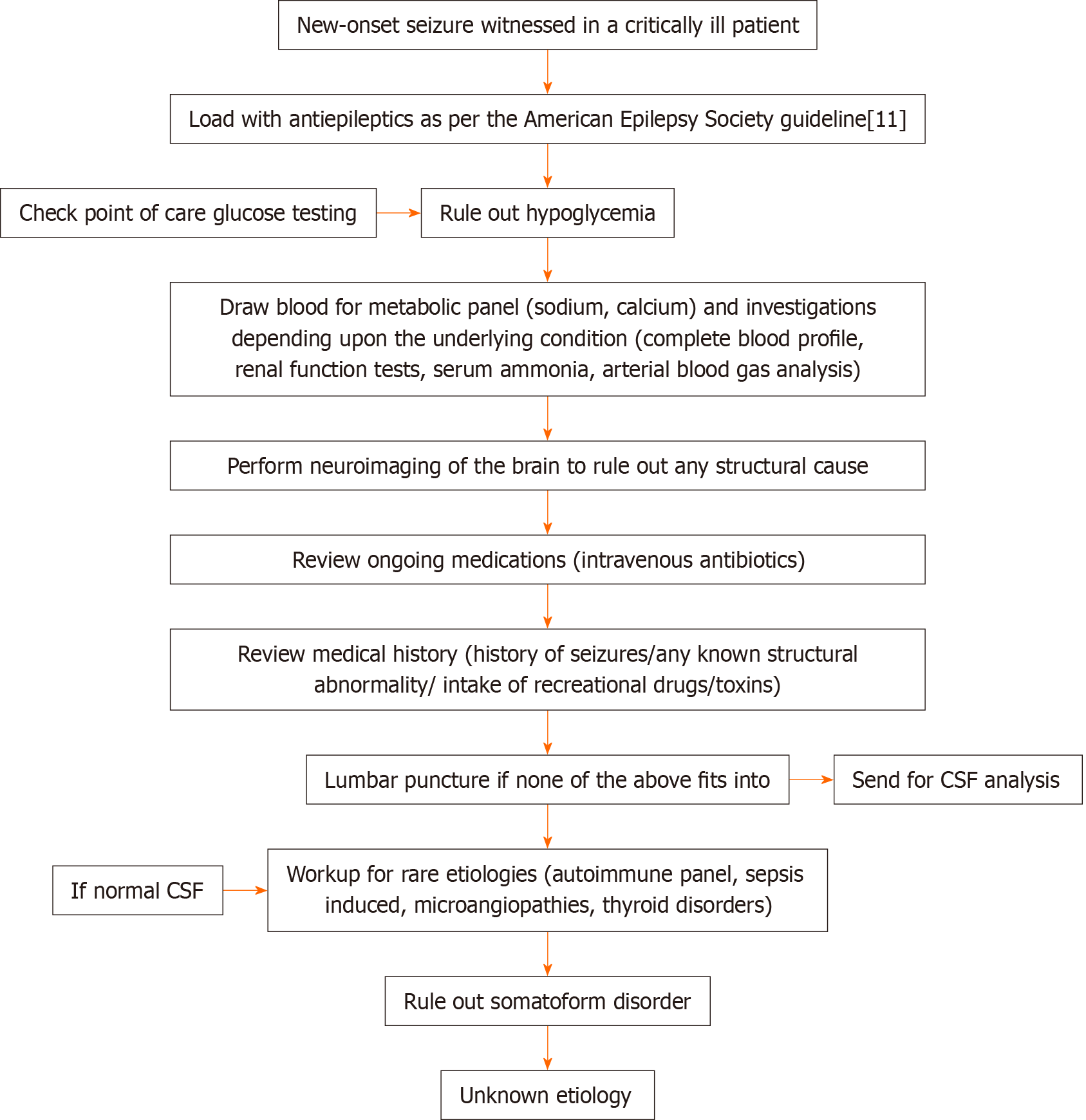

Two cases of alcohol withdrawal and five cases of toxicology-mediated seizures were observed in our enrolled patients, emphasizing the role of prompt history taking on recreational drugs and toxins and high clinical suspicion. Our approach is shown in Figure 1.

This study lists the causes of new-onset seizures in critically ill patients who otherwise had no predisposing factors to develop a seizure during ICU stay. Metabolic derangement-related seizures were the most common followed by tropical infections. These findings highlight the need for targeted monitoring and timely evaluation of patients who are at increased risk of developing seizures as well as incorporation of an algorithmic approach that can help with early diagnosis.

| 1. | Rubinos C, Ruland S. Neurologic Complications in the Intensive Care Unit. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Varelas PN, Spanaki MV, Mirski MA. Seizures and the neurosurgical intensive care unit. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2013;24:393-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pannem RB, Chintha VS. Aetiology of new onset seizures in cases admitted to an intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital: a two year study. Int J Adv Med. 2019;6:744. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Wagner AS, Semmlack S, Frei A, Rüegg S, Marsch S, Sutter R. Seizures and risks for recurrence in critically ill patients: an observational cohort study. J Neurol. 2022;269:4185-4194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13:S31-S34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 2639] [Article Influence: 377.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Parajuli S, Tiwari S, Gupta SK, Shakya YM, Shakya YL. Hyponatremia in Patients Admitted to Intensive Care Unit of a Tertiary Center: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2022;60:935-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Melchers M, van Zanten ARH. Management of hypocalcaemia in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2023;29:330-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zelaya JE, Al-Khoury L. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. 2022 May 1. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] |

| 9. | From: The Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine Tropical fever Group; Singhi S, Chaudhary D, Varghese GM, Bhalla A, Karthi N, Kalantri S, Peter JV, Mishra R, Bhagchandani R, Munjal M, Chugh TD, Rungta N. Tropical fevers: Management guidelines. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:62-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wanleenuwat P, Suntharampillai N, Iwanowski P. Antibiotic-induced epileptic seizures: mechanisms of action and clinical considerations. Seizure. 2020;81:167-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, Alldredge B, Arya R, Bainbridge J, Bare M, Bleck T, Dodson WE, Garrity L, Jagoda A, Lowenstein D, Pellock J, Riviello J, Sloan E, Treiman DM. Evidence-Based Guideline: Treatment of Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Children and Adults: Report of the Guideline Committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016;16:48-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 808] [Cited by in RCA: 837] [Article Influence: 83.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/