Published online Dec 9, 2024. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v13.i4.96755

Revised: August 12, 2024

Accepted: August 19, 2024

Published online: December 9, 2024

Processing time: 169 Days and 21.7 Hours

The initial trials on angiotensin II (AT II) administration indicated a high in

We describe a case of a patient presenting with catecholamine resistant septic shock, thrombocytopenia, deep vein thrombosis, and normal renin concentration who responded immediately to AT II treatment. We observed no worsening of thrombocytopenia and no progression of thrombosis or additional thromboses during treatment.

Our case underscores the need for individualized assessment of patients for po

Core Tip: Angiotensin II (AT II) is a relatively novel vasopressor used for the treatment of distributive shock in patients who do not respond adequately to treatment with noradrenaline. We describe a young patient with refractory septic shock who promptly responded to AT II despite low renin level. The patient also had severe thrombocytopenia and chronic venous thrombosis that was not aggravated during or after AT II administration. AT II may be a viable option for patients with thrombocytopenia and chronic venous thrombosis, specifically when there is a clear clinical requirement for increased vasopressor support.

- Citation: Vujaklija Brajkovic A, Markota A, Bielen L, Vujević A, Rora M, Radonic R. Angiotensin II administration in severe thrombocytopenia and chronic venous thrombosis: A case report. World J Crit Care Med 2024; 13(4): 96755

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v13/i4/96755.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v13.i4.96755

Angiotensin II (AT II) is a novel vasopressor for the treatment of vasoplegia in patients who do not respond adequately to noradrenaline[1]. Thrombocytopenia (9.8%–24%) and thromboembolic disease (13%) are common adverse reactions to AT II treatment. However, low platelet count is present in 22%–55% of patients with severe circulatory failure[2-4]. Addi

We report a case of a patient with vasoplegia associated with septic shock and concomitant severe thrombocytopenia and deep vein thrombosis who improved despite low renin concentration.

A 27-year-old Caucasian female was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to septic shock.

Symptoms started 3 d before admission with fever (up to 40.0 °C) and shivers.

Her past medical history included extensive digestive tract surgery at the age of 1 year due to volvulus, subsequent short bowel syndrome, and a need for total parenteral nutrition followed by numerous complications (thromboses and in

The family history is unremarkable.

At initial examination in the emergency department, the patient was alert and oriented, with hypotension (63/35 mmHg), tachycardia (96 bpm), and respiratory sufficient (16 breaths/min, SpO2 99% while breathing ambient air), and was afebrile (previously at home up to 40.0 °C with shivers). Initial Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was 11.

Laboratory tests indicated anemia and severe thrombocytopenia (erythrocytes 2.78 × 1012/L, hemoglobin 93 g/L, mean corpuscular volume 100.0 fL, leukocytes 5.9 × 109/L, band 1%, thrombocytes 18 × 109/L); inflammation (C-reactive protein 187.7 mg/L, procalcitonin 62.14 μg/L); disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (prothrombin time 0.55, activated partial thromboplastin time 47.4 s, fibrinogen 2.4 g/L, D-dimer 15.43 mg/L); acute kidney injury (creatinine 186 μmol/L, estimated glomerular filtration rate 31 mL/min/1.73 m2); and normal lactate concentration (1.4 mmol/L).

Focused bedside echocardiography revealed a hyperdynamic heart with good contractility (left ventricular ejection fraction 50%), inferior vena cava with a diameter of 20 mm, and an inspiratory collapse of > 50%.

Combined with the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis was septic shock.

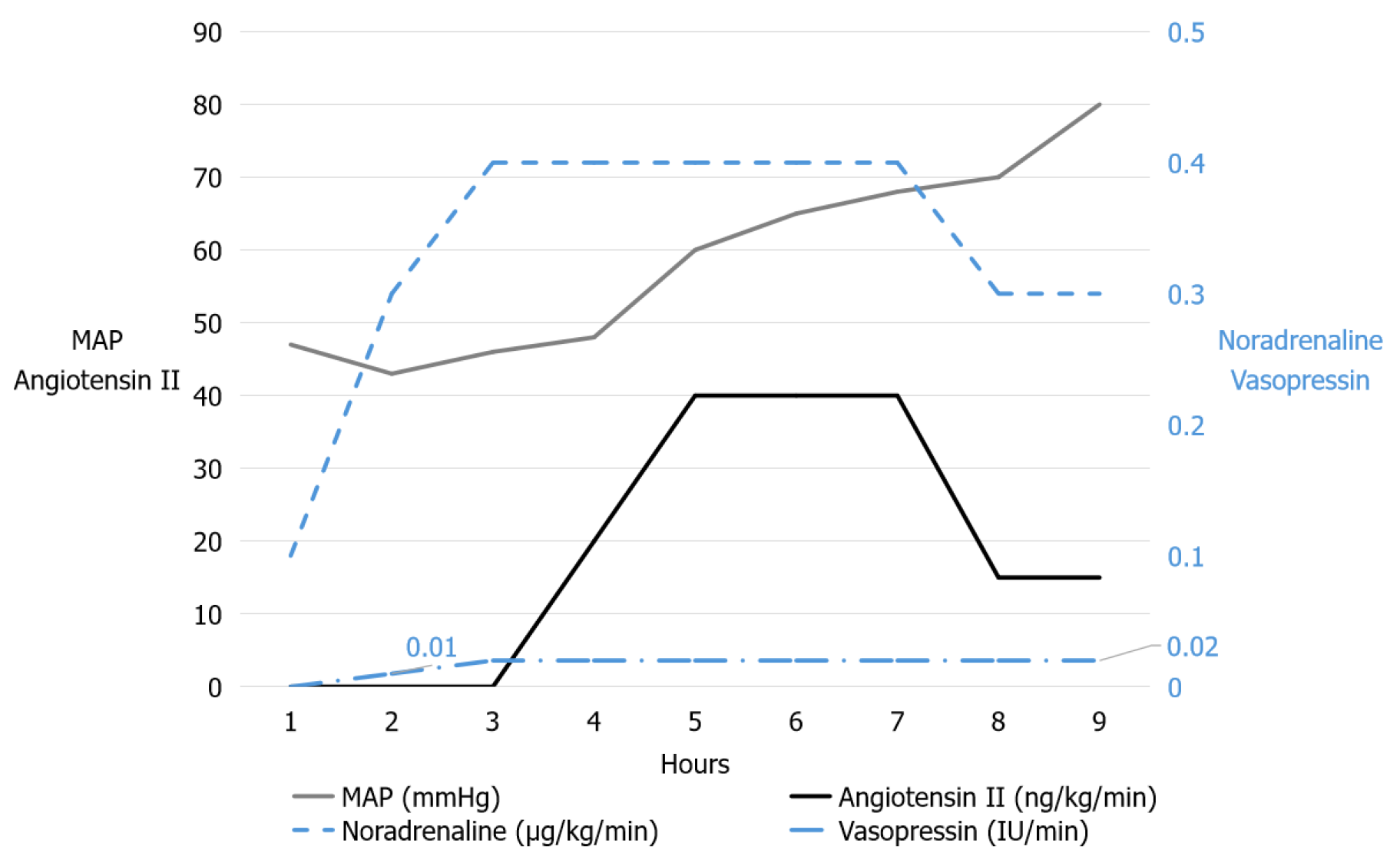

The patient received 2.5 L of crystalloids followed by empiric antibiotic therapy with meropenem. Due to persisting hypotension, infusion of noradrenaline was initiated and within 2 h reached a dose of 0.4 μg/kg/min, without an increase in mean arterial pressure (MAP) (46 mmHg), and with increasing lactate levels (6.1 mmol/L). Therefore, an infusion of vasopressin was added. The patient became anuric, lactate increased (8.4 mmol/L), and MAP remained < 50 mmHg. Due to distributive shock resistant to catecholamine (maximum dose of noradrenaline 0.4 μg/kg/min) and vasopressin (maximum dose 0.02 IU/min), and despite low platelet count (9 × 109/L) infusion of AT II was introduced. An increase in MAP to around 60 mmHg was reached within minutes with the initial infusion rate of 20 ng/kg/min. After 30 min, the infusion rate was increased to 40 ng/kg/min, and in the following hours the infusion rates of noradrenaline and vaso

The infusion of vasopressin was stopped 16 h after admission, and AT II was stopped 20 h after admission. At that time, noradrenaline was required at an infusion rate of 0.1 μg/kg/min and was withdrawn in the subsequent 12 h. The baseline serum renin concentration was 50.1 mIU/L (normal range: 4.2–60) and decreased to 43.4 mIU/L following AT II treatment. The patient also received IV corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 200 mg/d).

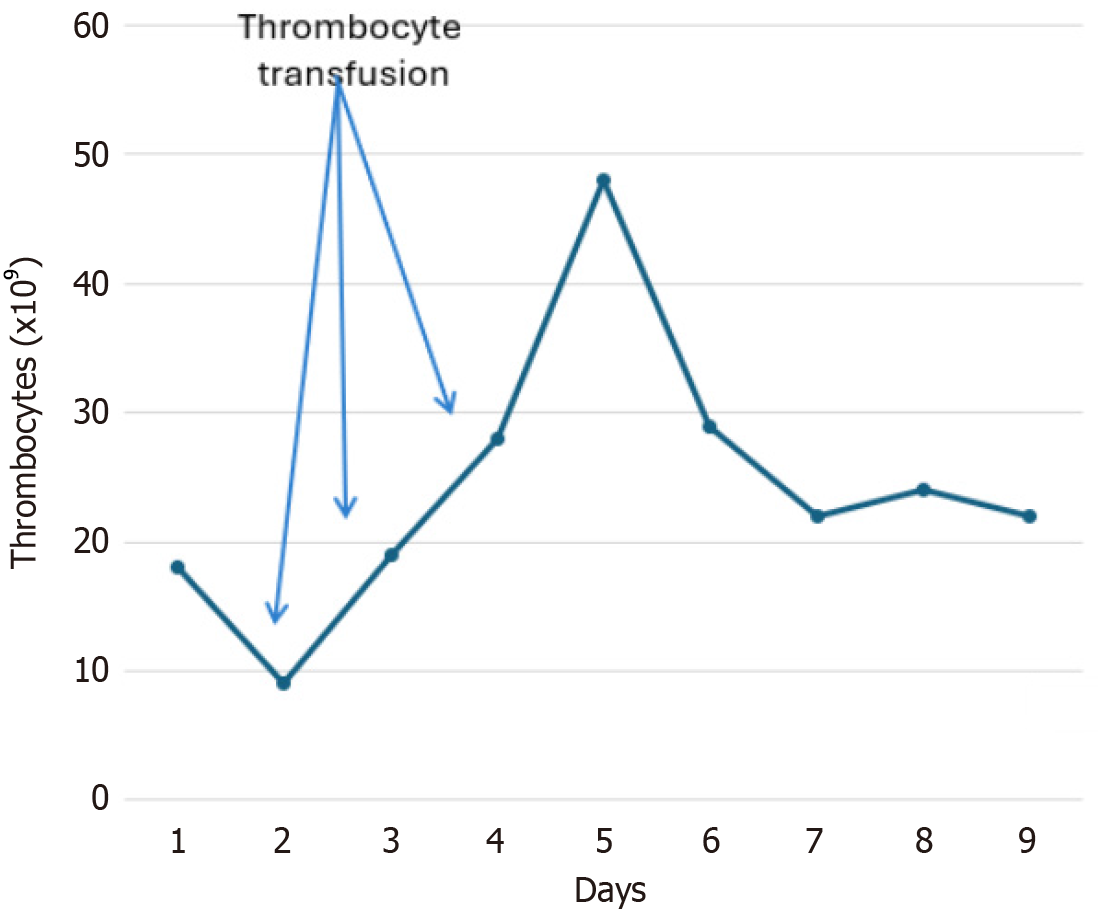

After ICU admission, thrombocytopenia worsened (9 × 109/L) but before administration of AT II (Figure 2). The patient received a platelet transfusion before the removal of the vascular access port and insertion of the new central line catheter, also before AT II administration.

Regular Color Doppler examinations ruled out new thrombosis as well as the progression of chronic subclavian vein thrombosis. Additionally, computed tomography (CT) venography performed after ICU discharge, but before hospital discharge, excluded the development of new thrombosis or progression of the existing subclavian thrombosis associated with AT II treatment.

Antibiotic therapy included meropenem, linezolid (due to allergy to vancomycin), and anidulafungin. Streptococcus species (viridans) and Staphylococcus haemolyticus were isolated from blood cultures and Enterobacter spp. and Candida albicans from the removed intravascular port catheter.

The patient responded well to therapy (removal of the infected port catheter and antimicrobial treatment) and was discharged from the ICU on day 10, and from the hospital on day 44. At hospital discharge, the platelet count was 110 × 109/L. On the regular examination in the outpatient clinic 1 mo after hospital discharge the patient was feeling well.

We described a case of a young patient with catecholamine-resistant vasodilatory shock presenting with severe thrombocytopenia and a history of chronic venous thrombosis who received AT II without worsening of thrombocytopenia or progression of chronic thrombosis or development of new thrombosis. Platelet count gradually improved with the sepsis resolution and platelet values at the discharge from the hospital were comparable to the prehospitalization values.

Both thrombocytopenia and deep vein thrombosis are considered adverse events associated with exogenous AT II usage. The ATHOS-3 trial reported increased incidence of thrombocytopenia with AT II use (9.8% vs 7%), and deep vein thrombosis (1.8% vs 0%)[2], which was later corroborated by the study of Wieruszewski et al[3] who reported thrombocytopenia in 24% and venous thrombosis in 3% of the retrospective cohort.

It remains challenging to conclusively attribute thrombocytopenia to AT II, as multiple factors can influence platelet count in patients with sepsis and septic shock. Decreased platelet count can be a consequence of platelet activation, decreased production, sequestration and increased consumption[5]. Nowadays, platelets are considered mediators of hemostasis as well as part of the innate immune system, known as immunothrombosis which is a normal physiological response to infection[6]. Many pathogens, including staphylococci and streptococci, can directly activate platelets leading towards thrombocytopenia[7]. The incidence of thrombocytopenia in septic shock is high, ranging from 30% to > 55%, and the severity of thrombocytopenia is associated with outcomes[4,8,9]. In more detail, patients with thrombocytopenia tend to have worse clinical outcomes expressed by higher SOFA score, the necessity for higher vasopressor dose, lower PaO2/FiO2 ratio, increased risk of bleeding, and consequently, higher overall mortality compared with patients who have normal platelet count[4,9-12]. In our patient, plausible causes of thrombocytopenia included DIC, splenomegaly/hypersplenism, micronutrient deficiency due to total parenteral nutrition, and polymicrobial sepsis.

The increased risk of thrombosis development with the use of AT II alongside existing chronic thrombosis and recent port catheter chamber thrombosis treatment posed a challenge. Given that the patient's condition was rapidly deteriorating, we decided to administer the medication while conducting daily ultrasound examinations of blood vessels. AT II did not induce new thrombosis nor aggravate chronic thrombosis, which was objectively assessed by CT venography performed after ICU discharge.

In the pursuit of personalized treatment for septic shock, renin has emerged as an indicator of patients who may benefit most from early initiation of AT II therapy. Elevated renin levels signal disruption in the renin–angioten

AT II rapidly and significantly improved MAP. No adverse effect on platelet count, thrombosis progression or new thrombosis development was observed with AT II administration. Even though the patient had normal renin concentration before AT II treatment, the response was immediate and followed by a decrease in renin. The present case indicates that AT II may be a viable consideration for patients with thrombocytopenia and chronic thrombosis, especially when there is a clear clinical requirement for increased vasopressor support.

We thank all physicians and nurses involved in the treatment of our patient.

| 1. | Tibi S, Zeynalvand G, Mohsin H. Role of the Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System in the Pathogenesis of Sepsis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Khanna A, English SW, Wang XS, Ham K, Tumlin J, Szerlip H, Busse LW, Altaweel L, Albertson TE, Mackey C, McCurdy MT, Boldt DW, Chock S, Young PJ, Krell K, Wunderink RG, Ostermann M, Murugan R, Gong MN, Panwar R, Hästbacka J, Favory R, Venkatesh B, Thompson BT, Bellomo R, Jensen J, Kroll S, Chawla LS, Tidmarsh GF, Deane AM; ATHOS-3 Investigators. Angiotensin II for the Treatment of Vasodilatory Shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:419-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 654] [Article Influence: 72.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wieruszewski PM, Wittwer ED, Kashani KB, Brown DR, Butler SO, Clark AM, Cooper CJ, Davison DL, Gajic O, Gunnerson KJ, Tendler R, Mara KC, Barreto EF. Angiotensin II Infusion for Shock: A Multicenter Study of Postmarketing Use. Chest. 2021;159:596-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharma B, Sharma M, Majumder M, Steier W, Sangal A, Kalawar M. Thrombocytopenia in septic shock patients--a prospective observational study of incidence, risk factors and correlation with clinical outcome. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:874-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Giustozzi M, Ehrlinder H, Bongiovanni D, Borovac JA, Guerreiro RA, Gąsecka A, Papakonstantinou PE, Parker WAE. Coagulopathy and sepsis: Pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and treatment. Blood Rev. 2021;50:100864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Engelmann B, Massberg S. Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:34-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 964] [Cited by in RCA: 1432] [Article Influence: 102.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cox D. Sepsis - it is all about the platelets. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1210219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim SM, Kim SI, Yu G, Kim JS, Hong SI, Kim WY. Hypercoagulability in Septic Shock Patients With Thrombocytopenia. J Intensive Care Med. 2022;37:721-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Péju E, Fouqué G, Charpentier J, Vigneron C, Jozwiak M, Cariou A, Mira JP, Jamme M, Pène F. Clinical significance of thrombocytopenia in patients with septic shock: An observational retrospective study. J Crit Care. 2023;76:154293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Menard CE, Kumar A, Houston DS, Turgeon AF, Rimmer E, Houston BL, Doucette S, Zarychanski R. Evolution and Impact of Thrombocytopenia in Septic Shock: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:558-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jiménez-Zarazúa O, González-Carrillo PL, Vélez-Ramírez LN, Alcocer-León M, Salceda-Muñoz PAT, Palomares-Anda P, Nava-Quirino OA, Escalante-Martínez N, Sánchez-Guzmán S, Mondragón JD. Survival in septic shock associated with thrombocytopenia. Heart Lung. 2021;50:268-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thiery-Antier N, Binquet C, Vinault S, Meziani F, Boisramé-Helms J, Quenot JP; EPIdemiology of Septic Shock Group. Is Thrombocytopenia an Early Prognostic Marker in Septic Shock? Crit Care Med. 2016;44:764-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bellomo R, Forni LG, Busse LW, McCurdy MT, Ham KR, Boldt DW, Hästbacka J, Khanna AK, Albertson TE, Tumlin J, Storey K, Handisides D, Tidmarsh GF, Chawla LS, Ostermann M. Renin and Survival in Patients Given Angiotensin II for Catecholamine-Resistant Vasodilatory Shock. A Clinical Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1253-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/