Published online Sep 9, 2022. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v11.i5.335

Peer-review started: January 20, 2022

First decision: April 13, 2022

Revised: May 29, 2022

Accepted: July 31, 2022

Article in press: July 31, 2022

Published online: September 9, 2022

Processing time: 229 Days and 3.8 Hours

Tracheo and broncho esophageal fistulas and their potential complications in adults are seldom encountered in clinical practice but carries a significant morbi

We present a case of a 39-year-old otherwise healthy man who presented to our hospital after ingestion of drain cleaner substance during a suicidal attempt. He unexpectedly suffered from cardiac arrest during his stay in the intensive care unit. The patient had developed extensive segmental trachea-broncho-esophageal fistulous tracks that led to a sudden and significant aspiration event of gastric and duodenal contents with subsequent cardiopulmonary arrest. Endoscopic evalu

The aim of this case presentation is to share with the reader the dire natural hist

Core Tip: Trachea-esophageal and broncho-esophageal in the setting of caustic ingestion is an unusual complication associated with high morbidity and mortality. Close monitoring of the gastrointestinal tract patency and motility is critical to avoid gastric distention and large aspiration events with detrimental consequences. Although there is no general consensus on the initial approach to patients with fistula formation, our case proposes serial esophagogastroduodenoscopy and flexible bronchoscopy for at least 6 mo as well as a low threshold for surgical referral when progression of disease or new findings are encountered.

- Citation: Lagrotta G, Ayad M, Butt I, Danckers M. Cardiac arrest due to massive aspiration from a broncho-esophageal fistula: A case report. World J Crit Care Med 2022; 11(5): 335-341

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v11/i5/335.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v11.i5.335

Injuries from caustic substance ingestion are associated with varying grades of damage to the gastr

A 39-year-old man arrived at our emergency department from another institution where he had been endotracheally intubated for airway protection.

The patient had sought medical attention five hours after a suicidal attempt where he ingested an unknown amount of drain cleaner liquid that contained sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, and carbonyl diamide.

The patient had a free previous medical history.

Upon arrival to our facility, his vital signs were stable. His physical exam revealed edematous oral mucosa and chemical injuries to the face.

His initial laboratory data was remarkable for a white blood cell count of 12.9 × 103/μL and a D-dimer > 5250 ng/mL DDU.

Chest computer tomography (CT) with contrast revealed thickening and submucosal edema of the esophageal and gastric wall, along with trace para-esophageal and peri-gastric stranding and fluid. No free air was reported.

Tracheo and broncho esophageal fistulas leading to massive aspiration and cardiac arrest.

He was started on a proton pump inhibitor, intravenous fluids, and prophylactic antibiotics. A trach

The patient’s hospital course was complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome and recurrent septic shock secondary to aspiration pneumonia. He was eventually liberated from mechanical venti

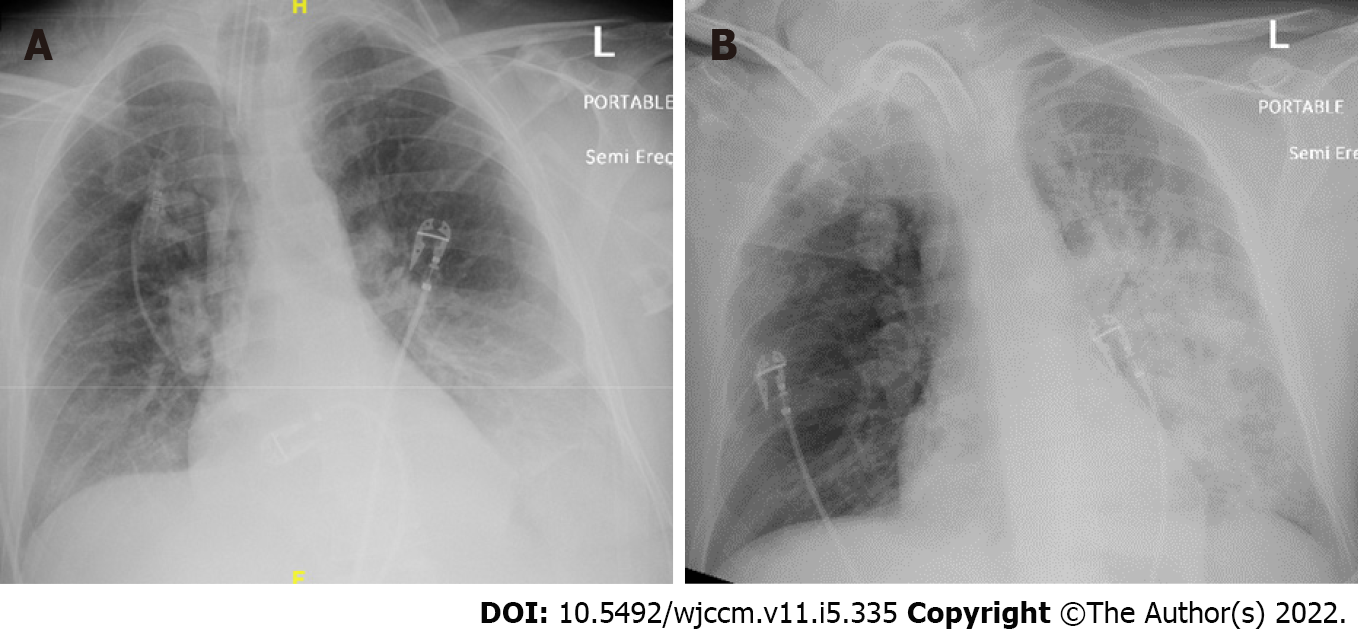

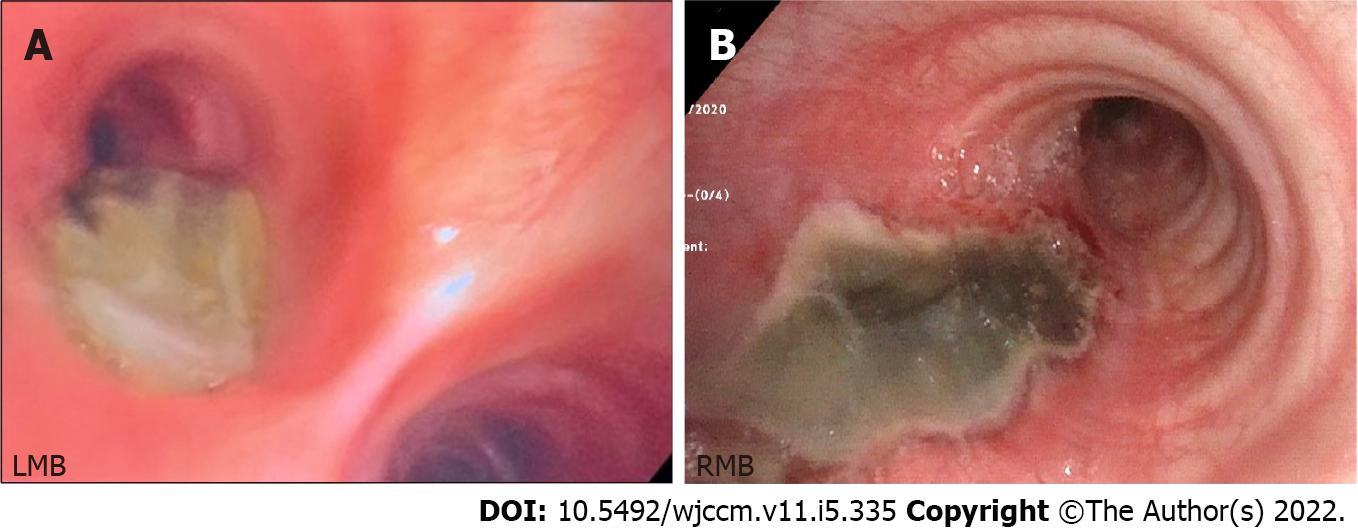

His endoscopy surveillance revealed progression and further extend of disease. Bronchoscopies performed on day 1 and day 8 as noted in Figure 2 demonstrate the progression of the insult. Bron

| Event | Time |

| Admission to hospital/ICU | Day 0 |

| EGD #1 | Day 0 |

| Bronchoscopy #1 | Day 1 |

| Bronchoscopy #2 | Day 8 |

| Cardiac arrest | Day 18 |

| Esophageal stent placement with EGD #2 | Day 22 |

| Bronchoscopy #3 | 7 wk |

| Hospital discharge | 16 wk |

| Bronchoscopy #4 | 17 wk |

| EGD #3 | 28 wk |

Caustic ingestion remains a rare but potentially catastrophic mechanism for injury leading to significant morbidity and mortality. Specific management guidelines have yet to be defined[2]. Injury severity is determined by multiple factors including type of agent, its concentration, amount consumed, and time of contact with gastrointestinal mucosa. Agents can be either acidic or alkali. Our patient ingested drain cleaner liquid, predominantly an alkali substance.

TEF is a delayed and unusual complication that occurs approximately in 3% of patients with caustic ingestion[2]. BEF are not extensively described in the literature and their true incidence unknown. The rarity of BEFs is likely due to the anatomical relationship between the left mainstem bronchus and the esophagus. The thoracic esophagus extends caudally towards the diaphragmatic hiatus, passing poste

Hemorrhage, thrombosis, and inflammation with edema occur within the first 24 h. If caustic ingestion is severe enough, transmural necrosis leads to perforation and regional fistulous tract formation. TEFs and BEFs can lead to sepsis, aspiration pneumonia, acute respiratory distress synd

Medical literature on the incidence of cardiopulmonary arrest due to aspiration through a BEF is lacking, and its incidence is not defined. We infer that our patient’s aspiration leading to his arrest was due to increased output through a persistently large fistulous track in the setting of transient duodenal outlet stenosis from mucosal damage and impaired gastrointestinal motility. Our patient exhibited large amounts of bile-colored tracheal secretions in the peri-arrest period confirming a high output fistulous passage of duodenal content. Although in our case the volume we aspirated through naso-gastric suctioning was 400-500 mL, the exact volume of gastric content aspirated is unknown. However, it was large enough to infiltrate the lingula and left lower lobe.

The incidence of aspiration pneumonia related to corrosive ingestion has been estimated in up to 4.2% of cases with a mortality up to 60%[4]. Due to high risk of aspiration, enteral nutrition is often restricted[4]. In addition, caloric restriction and malnutrition further lead to recurrent pulmonary infections, bronchopneumonia, and sepsis[5]. Alternative means of enteral nutrition through the insertion of a jejunostomy tube were sought in our patient to enhance nutritional state as well as to promote fistula healing. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for functional or anatomic gastrointestinal tract obstruction as a consequence of caustic injury and should be considered when addressing nutritional support to select the most suitable nutritional route.

Risk stratification is needed during the initial approach. Symptoms such as dysphagia, hematemesis, stridor, cough, respiratory distress, drooling, and abdominal pain have been described. A sudden bout of uncontrolled paroxysmal cough, a reported symptom associated with BEF[6], was witnessed in our patient while mechanically ventilated during daily sedation awakening trials suggesting aspiration events and persistent fistula.

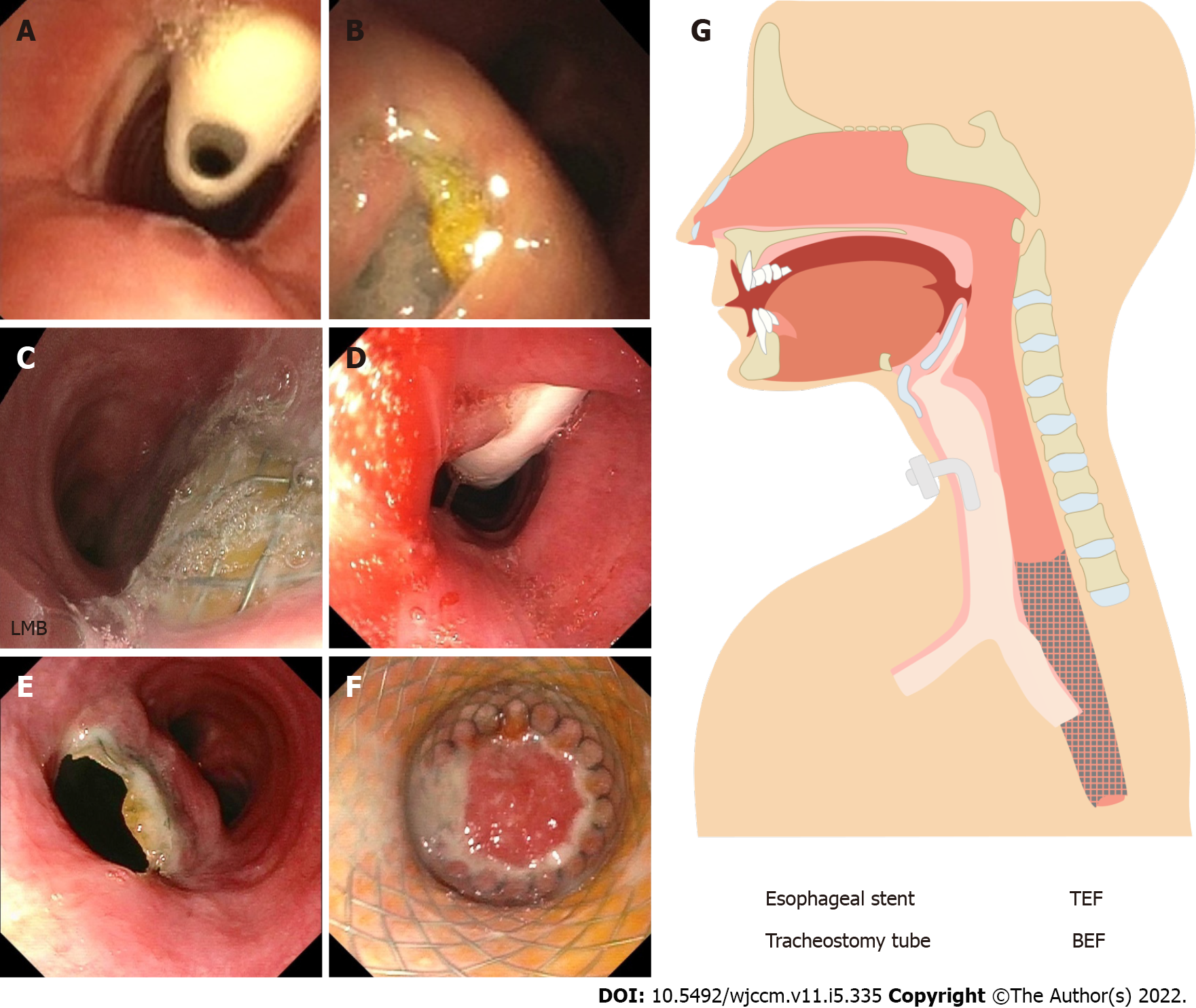

There is no consensus within the medical community of the initial and emergent management of TEF/BEF after caustic ingestion. In 2015, the World Society of Emergency Surgery recommended a management algorithm which includes both endoscopy and CT imaging as part of the initial assessment[7]. Our patient underwent both, esophagogastroduodenoscopy and non-contrast CT scan within the first twenty-four hours of ingestion. Figure 4 demonstrates initial esophagoduodenoscopy findings. In order to quantify the severity of the injury, we utilized the Zargar classification system which placed him in the IIIB category[8]. This grading is useful for predicting systemic complications, respiratory failure, nutritional autonomy, and survival. In general, the degree of esophageal injury at endoscopy is a predictor of systemic complication and death with a 9-fold increase in morbidity and mortality for every increased injury grade[9] which aligns with our case study. An important tool for the clinician about risk rather than timing.

However, risk stratification cannot accurately predict the depth of necrosis which could lead to inappropriate non-operative management and/or unnecessary surgical resection[2]. In order to properly evaluate the extent of necrosis, we propose that there is a benefit for surveillance endoscopic examination through EGD and flexible bronchoscopies for early fistula detection and therapeutic interventions. This would also serve for the monitoring of long term sequelae such as airway stenosis, or such in our case, further development of fistulous tracks. The interval of bronchoscopies would be dictated by endoscopic findings. In our case, evidence of a large newly detected TEF occurred 4 mo after the initial event. Prior biweekly and monthly bronchoscopies only reported the known BEF. It is reasonable to suggest monthly endoscopic surveillance in patients with high Zargar Score for at least 4-6 mo following the initial ingestion. In patients who are able to be discharged from the hospital, surgical referral should be sought if endoscopic examination does not show a favorable course, new fistulous tracks are detected, or if the patient’s symptoms severely impair quality of life.

The treatment of TEFs and BEFs is based on previous case reports, reviews, and case series, along with experts' opinions. In our case, a multidisciplinary team agreed on the placement of an 18 mm × 123 mm fully covered esophageal wall stent. According to the World Journal of Emergency Surgery, endoscopic treatment is the gold standard for closing large esophageal defects such suspected in our patient for the exam of injury during initial endoscopic examination. Self-expandable stents have showed to have a higher success rate and lower mortality rate when compared to surgical approach[10]. Our patient underwent self-expandable sent placement due to the clinical complexity and added surgical risk in the setting of a recent cardiac arrest. This case illustrates both the prolonged hospital course of a cardiac arrest survival due to delayed complications of a BEF associated with functional impairment and also the protracted progression of the disease more than 6 mo later.

In conclusion, TEF and BEF in the setting of caustic ingestion is an unusual complication associated with high morbidity and mortality. Early and frequent endoscopic evaluation of the upper gastrointestinal tract and bronchial tree, as well as maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion, are necessary for its prompt recognition. This will lead to early detection of delayed complications including new fistulous tracks, and timely institution of therapeutic interventions. We remind the reader of the importance of close monitoring of the gastrointestinal tract patency and motility to avoid gastric distention and large aspiration events with detrimental consequences. Although there is no general consensus on the initial approach to patients with fistula formation, our case proposes serial EGDs and flexible bronchoscopy for at least 6 mo as well as a low threshold for surgical referral when progression of disease or new findings are encountered.

The authors would like to acknowledgment Dr. Gonzalez H and Dr. Bethencourt-Mirabal A for the revision provided to the manuscript, and Dr. Kaplan S, Dr. Heller D and Dr. Morgan D, for their insight on the esophagoduodenoscopic and bronchoscopic findings.

| 1. | Ertekin C, Yanar H, Taviloglu K, Guloglu R, Alimoglu O. Can endoscopic injection of epinephrine prevent surgery in gastroduodenal ulcer bleeding? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14:147-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mircea C, Bonavina L, Kelly MD, Sarfati E, Cattan P. Caustic ingestion. Lancet. 2017;389:2041-2052. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Braden K, Urma D. Esophagus-anatomy and development. GI Motility. 2006;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Tseng YL, Wu MH, Lin MY, Lai WW. Outcome of acid ingestion related aspiration pneumonia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:638-643. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Argüder E, Aykun G, Karalezli A, Hasanoğlu HC. Bronchoesophageal fistula. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2012;19:47-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Aggarwal D, Mohapatra PR, Malhotra B. Acquired bronchoesophageal fistula. Lung India. 2009;26:24-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bonavina L, Chirica M, Skrobic O, Kluger Y, Andreollo NA, Contini S, Simic A, Ansaloni L, Catena F, Fraga GP, Locatelli C, Chiara O, Kashuk J, Coccolini F, Macchitella Y, Mutignani M, Cutrone C, Poli MD, Valetti T, Asti E, Kelly M, Pesko P. Foregut caustic injuries: results of the world society of emergency surgery consensus conference. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cheng HT, Cheng CL, Lin CH, Tang JH, Chu YY, Liu NJ, Chen PC. Caustic ingestion in adults: the role of endoscopic classification in predicting outcome. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zargar SA, Kochhar R, Mehta S, Mehta SK. The role of fiberoptic endoscopy in the management of corrosive ingestion and modified endoscopic classification of burns. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:165-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 10. | Chirica M, Kelly MD, Siboni S, Aiolfi A, Riva CG, Asti E, Ferrari D, Leppäniemi A, Ten Broek RPG, Brichon PY, Kluger Y, Fraga GP, Frey G, Andreollo NA, Coccolini F, Frattini C, Moore EE, Chiara O, Di Saverio S, Sartelli M, Weber D, Ansaloni L, Biffl W, Corte H, Wani I, Baiocchi G, Cattan P, Catena F, Bonavina L. Esophageal emergencies: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kumar N, India; Liu YC, China; Xu L, China S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gao CC