Published online Jan 9, 2022. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v11.i1.33

Peer-review started: April 29, 2021

First decision: June 17, 2021

Revised: June 21, 2021

Accepted: November 4, 2021

Article in press: November 4, 2021

Published online: January 9, 2022

Processing time: 251 Days and 2.1 Hours

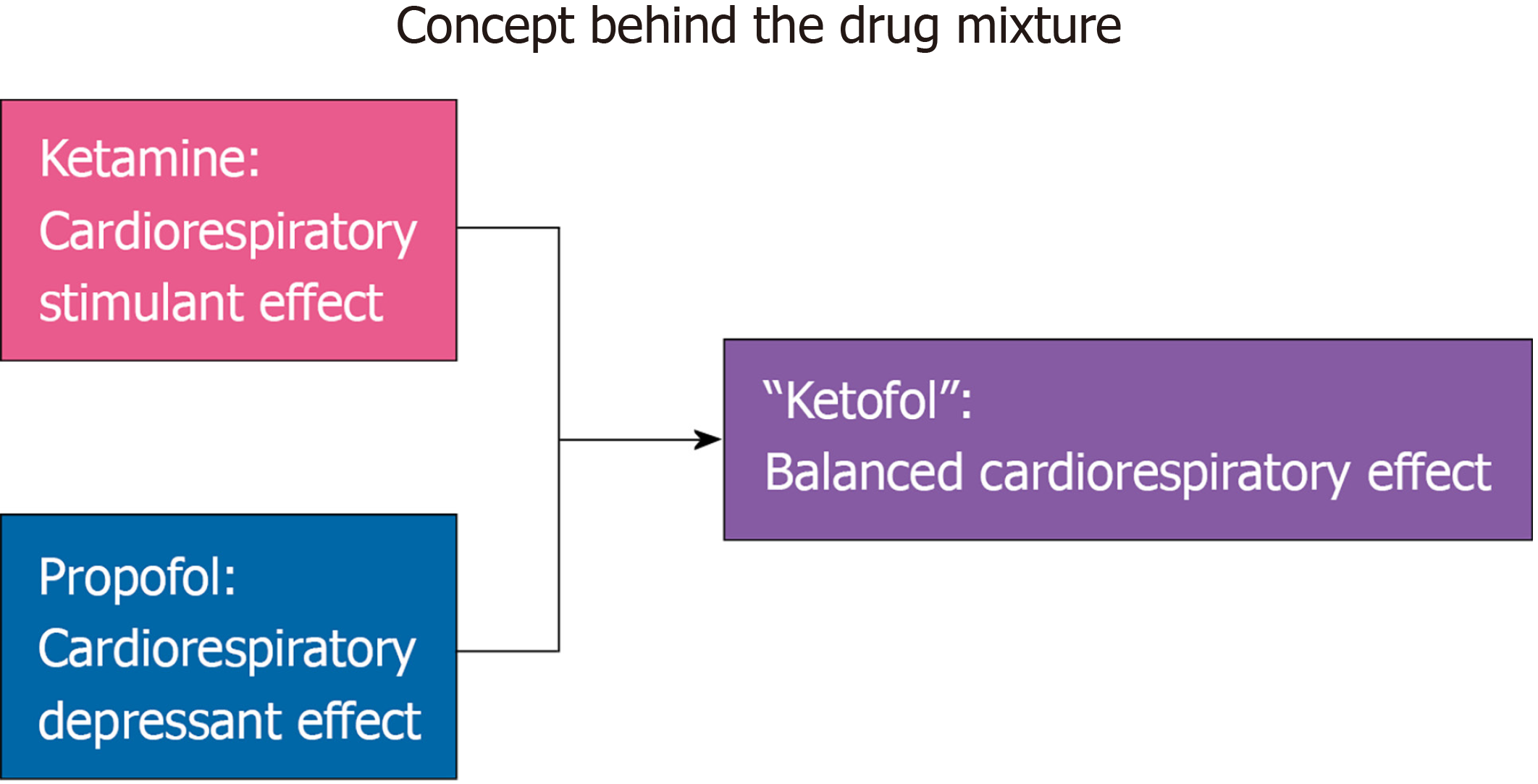

Endotracheal intubation is one of the most common, yet most dangerous procedure performed in the intensive care unit (ICU). Complications of ICU intubations include severe hypotension, hypoxemia, and cardiac arrest. Multiple observational studies have evaluated risk factors associated with these complications. Among the risk factors identified, the choice of sedative agents administered, a modifiable risk factor, has been reported to affect these complications (hypotension). Propofol, etomidate, and ketamine or in combination with benzodiazepines and opioids are commonly used sedative agents administered for endotracheal intubation. Propofol demonstrates rapid onset and offset, however, has drawbacks of profound vasodilation and associated cardiac depression. Etomidate is commonly used in the critically ill population. However, it is known to cause reversible inhibition of 11 β-hydroxylase which suppresses the adrenal production of cortisol for at least 24 h. This added organ impairment with the use of etomidate has been a potential contributing factor for the associated increased morbidity and mortality observed with its use. Ketamine is known to provide analgesia with sedation and has minimal respiratory and cardiovascular effects. However, its use can lead to tachycardia and hypertension which may be deleterious in a patient with heart disease or cause unpleasant hallucinations. Moreover, unlike propofol or etomidate, ketamine requires organ dependent elimination by the liver and kidney which may be problematic in the critically ill. Lately, a combination of ketamine and propofol, “Ketofol”, has been increasingly used as it provides a balancing effect on hemodynamics without any of the side effects known to be associated with the parent drugs. Furthermore, the doses of both drugs are reduced. In situations where a difficult airway is anticipated, awake intubation with the help of a fiberoptic scope or video laryngoscope is considered. Dexmedetomidine is a commonly used sedative agent for these procedures.

Core Tip: Intensive care unit endotracheal intubations are associated with a higher risk of complications such as hypotension, hypoxemia, and cardiac arrest when compared to non-intensive care unit endotracheal intubations. A necessity of endotracheal intubations, sedation, is a modifiable risk factor in the pathway to cardiovascular instability. The goal of this review is to present the pros and cons of each sedative agent used for endotracheal intubation while comparing the outcomes. This will help the reader to make an informed decision when choosing a sedative agent for endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit.

- Citation: Tarwade P, Smischney NJ. Endotracheal intubation sedation in the intensive care unit. World J Crit Care Med 2022; 11(1): 33-39

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v11/i1/33.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v11.i1.33

Endotracheal intubations are one of the most common, yet most dangerous procedures performed in the intensive care unit (ICU). Complications from ICU endotracheal intubations are seen in approximately 40%-45% of patients and include severe hypotension (10%-43%), severe hypoxemia (9%-25%), and cardiac arrest(2%-3%)[1]. Severe cardiovascular collapse is one of the most common complications after ICU endotracheal intubation[2]. Understandably, identification of risk factors for cardiovascular collapse surrounding endotracheal intubation becomes extremely imperative to mitigate or avoid this devastating complication. In a multicenter observational study, Perbet et al[2] identified patient risk factors for cardiovascular collapse which included advanced patient age, higher sequential organ failure assessment score, acute respiratory failure, brain injury, trauma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Procedural risk factors included multiple intubations, use of propofol for induction, and desaturation during intubation[2]. Recently, a multicenter observational prospective study derived and validated a hypotension prediction score for patients undergoing endotracheal intubation in the ICU. The investigators identified 11 variables (increasing illness severity; increasing age; sepsis diagnosis; endotracheal intubation in the setting of cardiac arrest, mean arterial pressure < 65 mmHg, and acute respiratory failure; diuretic use 24 h preceding endotracheal intubation; decreasing systolic blood pressure from 130 mmHg; catecholamine or phenylephrine use immediately prior to endotracheal intubation; and use of etomidate during endotracheal intubation) that were independently associated with peri-intubation hypotension with a C-statistic of 0.75 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.72-0.78]. Of the 11 variables, the use of etomidate was found to protect against peri-intubation hypotension[3].

Incidence of adverse events like death or hypoxic brain damage are higher with intubations done in ICUs compared to those performed in the operating rooms[4]. In contrast to the ICU, endotracheal intubations in the operating room are frequently performed in a controlled fashion under non-emergent conditions. Although patients may have numerous comorbidities, personnel are specifically trained in airway management, and due to the elective nature of surgical procedures, preparations can be made for difficulties encountered[5,6].

Thus, based on the above evidence, preparation and planning for endotracheal intubations is paramount in critically ill patients to avoid life-threatening complications. An element of endotracheal intubation that is modifiable is the choice of sedative agents administered, which as the evidence suggests, may alter ICU complications, in particular, severe hypotension.

Propofol is currently the most common anesthetic induction agent used worldwide. Its rapid onset and short duration of action is ideally suited to settings such as the ICU. Propofol’s sedative effects are mediated through gamma aminobutyric acid receptors with some activity on N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Termination of action of propofol is by redistribution and is independent of organ elimination, thereby making it very useful in ICU patients who may have organ impairment. Standard induction doses of propofol in a healthy adult are 2-2.5mg/kg[7]. However, dosing in the ICU is dramatically different due to the nature of the patent population with patients usually requiring endotracheal intubation for acute respiratory failure or cardiovascular collapse as illustrated recently[1]. In fact, propofol has been shown to have increased potency in shock states indicating less is more[8]. This finding demonstrates the profound vasodilatory effects and associated cardiac depression of propofol[7]. For the healthy patient, this is well tolerated but in patients who are in septic or cardiogenic shock, this attribute can have a detrimental effect on patient hemodynamics. Hence, caution is warranted when using propofol in the critically ill population. A recent study evaluating intubation practices in critically ill patients from 29 countries showed that propofol is the most used sedative and was significantly associated with hemodynamic instability in 63.7% of patients who exhibited precarious hemodynamics, as compared to etomidate with only 49.5% of patients developing hemo

Ketamine is an anesthetic agent which causes complete anesthesia while providing analgesia at the same time. In addition, its causes less respiratory depression and has hemodynamic effects that are opposite that of propofol[7]. This property makes it a desired drug in multiple settings. It is a phencyclidine derivative which acts on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor[10,11]. The standard induction dose of ketamine is 1-2 mg/kg. Ketamine’s hemodynamic effects are mediated through central nervous system stimulation and inhibition of catecholamine reuptake. However, it is also a known direct myocardial depressant. Thus, in severely ill patients such as the patient in septic shock who is depleted of catecholamines, the direct myocardial depressant effects can be unmasked[7,12]. In addition, ketamine may cause increased intracranial pressure through increased cerebral perfusion thereby limiting its use in trauma patients[13]. Lastly, ketamine is known to induce salivation which can be problematic in airway management in the setting of difficult airways where visualization of the airway is paramount[7]. Although medications such as atropine or glycopyrrolate can be administered to help reduce this effect, these medications may alter the patient’s hemodynamics which may not be desirable. When compared to etomidate in the setting of rapid sequence intubation for trauma patients, no significant difference was observed for peri-intubation outcomes such as first pass intubation success, need for rescue surgical airway, and peri-intubation cardiac arrest. However, ketamine was associated with lower odds of hospital acquired sepsis [adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.72, 95%CI: 0.52-0.99] but higher number of days on vasopressor therapy (adjusted OR 0.74 95%CI: 0.58-0.95)[14]. Another trial which compared these two agents was the Ketased trial which failed to show any difference in immediate post-intubation complications, catecholamine free days at day 28, or 28-d mortality[15].

Etomidate is an anesthetic induction agent commonly used because of its ability to maintain stable hemodynamics. Etomidate causes sedation by its agonistic action on gamma aminobutyric acid receptors and it is thought to maintain hemodynamics through simultaneous stimulation of α-2b adrenoreceptors[16]. In addition to this, etomidate also reversibly inhibits 11β-hydroxylase and therefore suppresses the adrenal production of cortisol for at least 24 h after a single induction dose[17]. This specific adverse effect is a major reason that causes many intensivists to shy away from using etomidate in the critically ill. Furthermore, the use of etomidate for endotracheal intubation in septic patients has been associated with increased mortality and poor outcomes[18-20]. Moreover, this trend has been seen in surgical patients[21]. For example, a study at Cleveland Clinic in non-cardiac surgery patients showed that patients who received etomidate had a 2.5 (98%CI: 1.9–3.4) higher odds of dying than those who received propofol anesthesia. In addition, patients who received etomidate had a prolonged hospital stay without a significant difference in intraoperative vasopressor requirements[21]. A recent metanalysis that included 29 trials totaling 8584 patients comparing etomidate with other induction agents demonstrated that etomidate was associated with adrenal insufficiency [risk ratio (RR) = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.42, 1.67, P < 0.001] and increased overall relative mortality rates (RR = 1.09, 95%CI: 1.04, 1.16, P = 0.001). However, on meta-regression, the increased mortality was associated with increasing severity of disease[22]. Hence, the association between etomidate and increased mortality should be interpreted with caution. It is likely that etomidate does lead to additional organ dysfunction, through adrenal suppression, in the critically ill resulting in possibly increased morbidity and mortality.

In the past, high doses of benzodiazepines and opioids were used for sedation during endotracheal intubation. However, with the association of benzodiazepines and increased delirium combined with the awareness to maintain lighter sedation levels, these practices have decreased[23,24].

Lately, a combination of two sedatives, namely ketamine and propofol (“Ketofol”), has demonstrated efficacy in terms of hemodynamic preservation when sedating for airway management. This is supported by two randomized controlled trials in which “Ketofol” was compared to propofol only and to half-dose etomidate. In addition to the hemodynamic stability offered by “Ketofol”, both trials also suggested that “Ketofol” reduced opioid requirements as compared to the competitor[25,26]. In one trial, “Ketofol” was associated with reduced transfusion requirements as compared to etomidate due to cortisol’s role in maintaining vascular homoeostasis (inhibited by etomidate)[26]. Other systemic reviews and meta-analyses have suggested that “Ketofol” is associated with less respiratory events than propofol alone[27,28]. Thus, this unique drug combination has the ability to cause less hemodynamic alterations than either parent compound while providing non-opioid pain control, which may translate into improved metrics such as reduction in post-intubation hypotension and therefore, morbidity and mortality.

An ideal anesthetic is one that has a balanced effect on the cardiopulmonary system while providing hypnosis and analgesia[7]. The “Ketofol” admixture possesses these qualities and as such, its use is applicable to a variety of patient care settings. The rationale behind the drug combination is to provide an admixture that when used together, attenuates blood pressure swings and provides a smooth blood pressure profile during endotracheal intubation and beyond (Figure 1). Although this depends on dosing used for both individual medications, most of the evidence points to a stabilizing effect on blood pressure. This stabilization has the potential to translate into direct and indirect benefits to patients across multiple hospital settings (e.g., emergency room, ICU, operating room, procedural suites) throughout the world. For example, the admixture may offer neuroprotection via maintenance of cerebral perfusion through mean arterial pressure, which may reduce post-ICU psychological phenomena (e.g., cognitive dysfunction, depression, etc.) in long-term critical care survivors as well as delirium in surgical patients through reduction of benzo

Use of muscle relaxants also varies for endotracheal intubations in the ICU. An observational study comparing outcomes of intubation with or without the use of muscle relaxants failed to show any significant difference in post intubation complications, however, it did show that excellent intubation conditions were achieved in patients in which muscle relaxants were used[31]. Another observational study showed higher first attempt success rate when neuromuscular blockers were used (80.9% vs 69.6%, P = 0.003)[32].

There are many unique occasions which affect the choice of sedatives in the ICU other than those mentioned above. Cardiac arrest is one such occasion. Typically, no drugs are administered during the intubation. For difficult airways, sedatives may be chosen that provide quick onset and offset or have specific reversal agents associated with their use. Burns, angioedema, and superior vena cava syndrome are some examples when awake fiberoptic intubation might be preferred over routine intubation. In addition, another setting in which sedatives are altered from the usual intubation practice include awake video laryngoscopy, which has been increasingly used to avoid a lost airway or spontaneous respirations[33]. Dexmedetomidine has been used during these situations, along with topical anesthesia, due to its anxiolytic effect with minimal adverse effects on spontaneous respirations[34].

Endotracheal intubation is a common procedure, yet can be associated with devastating complications, namely hypoxemia and cardiovascular collapse, that increase when conducted outside a controlled setting such as the operating room. Sedation is frequently administered to facilitate this procedure. However, sedation can sometimes exacerbate these complications, especially relevant when endotracheal intubation is carried out in an urgent/emergent context (e.g., ICU, emergency department, etc.). Several sedatives are available to facilitate airway management. Each has its own drawbacks as discussed above which the clinician needs to take into consideration when performing this procedure. As an alternative to the individual sedatives, a combination of sedatives may be needed to achieve the desired outcome such as “Ketofol” in which available evidence suggests a hemodynamic sparring effect with reduced opioid requirements.

| 1. | Russotto V, Myatra SN, Laffey JG, Tassistro E, Antolini L, Bauer P, Lascarrou JB, Szuldrzynski K, Camporota L, Pelosi P, Sorbello M, Higgs A, Greif R, Putensen C, Agvald-Öhman C, Chalkias A, Bokums K, Brewster D, Rossi E, Fumagalli R, Pesenti A, Foti G, Bellani G; INTUBE Study Investigators. Intubation Practices and Adverse Peri-intubation Events in Critically Ill Patients From 29 Countries. JAMA. 2021;325:1164-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 77.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Perbet S, De Jong A, Delmas J, Futier E, Pereira B, Jaber S, Constantin JM. Incidence of and risk factors for severe cardiovascular collapse after endotracheal intubation in the ICU: a multicenter observational study. Crit Care. 2015;19:257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Smischney NJ, Kashyap R, Khanna AK, Brauer E, Morrow LE, Seisa MO, Schroeder DR, Diedrich DA, Montgomery A, Franco PM, Ofoma UR, Kaufman DA, Sen A, Callahan C, Venkata C, Demiralp G, Tedja R, Lee S, Geube M, Kumar SI, Morris P, Bansal V, Surani S; SCCM Discovery (Critical Care Research Network of Critical Care Medicine) HEMAIR Investigators Consortium. Risk factors for and prediction of post-intubation hypotension in critically ill adults: A multicenter prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cook TM, Woodall N, Frerk C; Fourth National Audit Project. Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 1: anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:617-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1171] [Cited by in RCA: 1317] [Article Influence: 87.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Divatia JV, Khan PU, Myatra SN. Tracheal intubation in the ICU: Life saving or life threatening? Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:470-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Taboada M, Doldan P, Calvo A, Almeida X, Ferreiroa E, Baluja A, Cariñena A, Otero P, Caruezo V, Naveira A, Alvarez J. Comparison of Tracheal Intubation Conditions in Operating Room and Intensive Care Unit: A Prospective, Observational Study. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:321-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Cohen NH, Young WL. Miller's anesthesia e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014. |

| 8. | Johnson KB, Egan TD, Kern SE, McJames SW, Cluff ML, Pace NL. Influence of hemorrhagic shock followed by crystalloid resuscitation on propofol: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:647-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Koenig SJ, Lakticova V, Narasimhan M, Doelken P, Mayo PH. Safety of Propofol as an Induction Agent for Urgent Endotracheal Intubation in the Medical Intensive Care Unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2015;30:499-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Flood P, Rathmell JP, Shafer S. Stoelting's pharmacology and physiology in anesthetic practice. 5th ed. LWW, 2015. |

| 11. | Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Dell'Avvocata F, Faggian G, Conte L, Giatti S, Michielan F, Roncon L. Ketamine and midazolam differently impact post-intubation hemodynamic profile when used as induction agents during emergency airway management in hemodynamically stable patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels. 2018;33:213-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dewhirst E, Frazier WJ, Leder M, Fraser DD, Tobias JD. Cardiac arrest following ketamine administration for rapid sequence intubation. J Intensive Care Med. 2013;28:375-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Filanovsky Y, Miller P, Kao J. Myth: Ketamine should not be used as an induction agent for intubation in patients with head injury. CJEM. 2010;12:154-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Upchurch CP, Grijalva CG, Russ S, Collins SP, Semler MW, Rice TW, Liu D, Ehrenfeld JM, High K, Barrett TW, McNaughton CD, Self WH. Comparison of Etomidate and Ketamine for Induction During Rapid Sequence Intubation of Adult Trauma Patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69:24-33.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jabre P, Combes X, Lapostolle F, Dhaouadi M, Ricard-Hibon A, Vivien B, Bertrand L, Beltramini A, Gamand P, Albizzati S, Perdrizet D, Lebail G, Chollet-Xemard C, Maxime V, Brun-Buisson C, Lefrant JY, Bollaert PE, Megarbane B, Ricard JD, Anguel N, Vicaut E, Adnet F; KETASED Collaborative Study Group. Etomidate vs ketamine for rapid sequence intubation in acutely ill patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:293-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Paris A, Philipp M, Tonner PH, Steinfath M, Lohse M, Scholz J, Hein L. Activation of alpha 2B-adrenoceptors mediates the cardiovascular effects of etomidate. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:889-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jung B, Clavieras N, Nougaret S, Molinari N, Roquilly A, Cisse M, Carr J, Chanques G, Asehnoune K, Jaber S. Effects of etomidate on complications related to intubation and on mortality in septic shock patients treated with hydrocortisone: a propensity score analysis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sunshine JE, Deem S, Weiss NS, Yanez ND, Daniel S, Keech K, Brown M, Treggiari MM. Etomidate, adrenal function, and mortality in critically ill patients. Respir Care. 2013;58:639-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chan CM, Mitchell AL, Shorr AF. Etomidate is associated with mortality and adrenal insufficiency in sepsis: a meta-analysis*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2945-2953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Albert SG, Ariyan S, Rather A. The effect of etomidate on adrenal function in critical illness: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:901-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Komatsu R, You J, Mascha EJ, Sessler DI, Kasuya Y, Turan A. Anesthetic induction with etomidate, rather than propofol, is associated with increased 30-day mortality and cardiovascular morbidity after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:1329-1337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Albert SG, Sitaula S. Etomidate, Adrenal Insufficiency and Mortality Associated With Severity of Illness: A Meta-Analysis. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;885066620957596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Slattum P, Van Ness PH, Inouye SK. Benzodiazepine and opioid use and the duration of intensive care unit delirium in an older population. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hughes CG, McGrane S, Pandharipande PP. Sedation in the intensive care setting. Clin Pharmacol. 2012;4:53-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Smischney NJ, Beach ML, Loftus RW, Dodds TM, Koff MD. Ketamine/propofol admixture (ketofol) is associated with improved hemodynamics as an induction agent: a randomized, controlled trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:94-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Smischney NJ, Nicholson WT, Brown DR, Gallo De Moraes A, Hoskote SS, Pickering B, Oeckler RA, Iyer VN, Gajic O, Schroeder DR, Bauer PR. Ketamine/propofol admixture vs etomidate for intubation in the critically ill: KEEP PACE Randomized clinical trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87:883-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ghojazadeh M, Sanaie S, Paknezhad SP, Faghih SS, Soleimanpour H. Using Ketamine and Propofol for Procedural Sedation of Adults in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Pharm Bull. 2019;9:5-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yan JW, McLeod SL, Iansavitchene A. Ketamine-Propofol Versus Propofol Alone for Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:1003-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | CDC/NCHS National Hospital Discharge Survey. Number of all-listed procedures for discharges from short-stay hospitals, by procedure category and age: United States, 2010. [cited 10 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/4procedures/2010pro4_numberprocedureage.pdf. |

| 30. | United States Department of Health and Human Services. About the epidemic 2019. [cited 10 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index.html. |

| 31. | Baillard C, Adnet F, Borron SW, Racine SX, Ait Kaci F, Fournier JL, Larmignat P, Cupa M, Samama CM. Tracheal intubation in routine practice with and without muscular relaxation: an observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2005;22:672-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mosier JM, Sakles JC, Stolz U, Hypes CD, Chopra H, Malo J, Bloom JW. Neuromuscular blockade improves first-attempt success for intubation in the intensive care unit. A propensity matched analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:734-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Alhomary M, Ramadan E, Curran E, Walsh SR. Videolaryngoscopy vs. fibreoptic bronchoscopy for awake tracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:1151-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tang ZH, Chen Q, Wang X, Su N, Xia Z, Wang Y, Ma WH. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of remifentanil and dexmedetomidine for awake fiberoptic endoscope intubation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e25324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Protopapas AA, Shetabi H S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu M