Published online May 9, 2021. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v10.i3.47

Peer-review started: January 19, 2021

First decision: February 15, 2021

Revised: February 19, 2021

Accepted: April 22, 2021

Article in press: April 22, 2021

Published online: May 9, 2021

Processing time: 108 Days and 17 Hours

Recent studies of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) demonstrated that obesity is significantly associated with increased disease severity, clinical outcome, and mortality. The association between hepatic steatosis, which frequently accompanies obesity, and the pneumonia severity score (PSS) evaluated on computed tomography (CT), and the prevalence of steatosis in patients with COVID-19 remains to be elucidated.

To assess the frequency of hepatic steatosis in the chest CT of COVID-19 patients and its association with the PSS.

The chest CT images of 485 patients who were admitted to the emergency department with suspected COVID-19 were retrospectively evaluated. The patients were divided into two groups as COVID-19-positive [CT- and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-positive] and controls (CT- and RT-PCR-negative). The CT images of both groups were evaluated for PSS as the ratio of the volume of involved lung parenchyma to the total lung volume. Hepatic steatosis was defined as a liver attenuation value of ≤ 40 Hounsfield units (HU).

Of the 485 patients, 56.5% (n = 274) were defined as the COVID-19-positive group and 43.5% (n = 211) as the control group. The average age of the COVID-19-positive group was significantly higher than that of the control group (50.9 ± 10.9 years vs 40.4 ± 12.3 years, P < 0.001). The frequency of hepatic steatosis in the positive group was significantly higher compared with the control group (40.9% vs 19.4%, P < 0.001). The average hepatic attenuation values were significantly lower in the positive group compared with the control group (45.7 ± 11.4 HU vs 53.9 ± 15.9 HU, P < 0.001). Logistic regression analysis showed that after adjusting for age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight, and obesity there was almost a 2.2 times greater odds of hepatic steatosis in the COVID-19-positive group than in the controls (odds ratio 2.187; 95% confidence interval: 1.336-3.580, P < 0.001).

The prevalence of hepatic steatosis was significantly higher in COVID-19 patients compared with controls after adjustment for age and comorbidities. This finding can be easily assessed on chest CT images.

Core Tip: We evaluated the frequency of hepatic steatosis in the computed tomography (CT) of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients and its association with the pneumonia severity score (PSS). We retrospective evaluated the CTs of 485 patients with suspected COVID-19. Regression analysis showed that after adjusting for age and comorbidities there was almost a 2.2 times greater odds of hepatic steatosis in the COVID-19-positive group than in controls (odds ratio 2.187; 95% confidence interval: 1.336-3.580, P < 0.001). There was a positive correlation between hepatic steatosis and PSS. The study revealed a significantly higher prevalence of hepatic steatosis on CT in COVID-19 patients compared with controls.

- Citation: Tahtabasi M, Hosbul T, Karaman E, Akin Y, Kilicaslan N, Gezer M, Sahiner F. Frequency of hepatic steatosis and its association with the pneumonia severity score on chest computed tomography in adult COVID-19 patients. World J Crit Care Med 2021; 10(3): 47-57

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v10/i3/47.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v10.i3.47

An unknown infection that first appeared as a pneumonia cluster in Wuhan, China was later found to be caused by a new betacoronavirus species, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease was named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)[1,2]. The infection rapidly spread in Japan, South Korea, and Thailand. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern for COVID-19, evaluating its pandemic potential[3]. SARS-CoV-2, which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome, has resulted in the death of nearly two million people worldwide within the last year, and continues to pose serious concerns[4]. Risk factors associated with severe infection and mortality in COVID-19 include hypertension, severe obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney and liver disease, male gender, and advanced age[5,6]. Obesity has also been shown to be associated with progression to severe pneumonia associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, need for hospitalization and mechanical ventilation because of acute respiratory failure, diffuse coagulopathy, and increased mortality risk[7]. In fact, morbid obesity has been identified as one of the most important risk factors in young adults with COVID-19[8]. Obesity is considered to play an important role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 as it increases vulnerability to infections and adverse effects of the chronic inflammation of adipose tissue on the immune system resulting from metabolic dysfunction[9]. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) caused by ongoing metabolic abnormalities appears to be a potential risk factor for developing SARS-CoV-2 infection and its associated complications[10]. NAFLD is considered a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome, including obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance. The risk of severe COVID-19 can thus also be attributed to impaired liver function as a result of NAFLD[10]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the possible relationship between hepatic steatosis and COVID-19 infection severity based on computed tomography (CT) to evaluate liver attenuation, which is a non-invasive approach that can be used to identify the presence of hepatic steatosis during pulmonary CT examinations without any additional procedures.

This retrospective study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Harran University (date: 07.12.2020 and session: 20). Informed consent was waived given the retrospective nature and characteristics of the study.

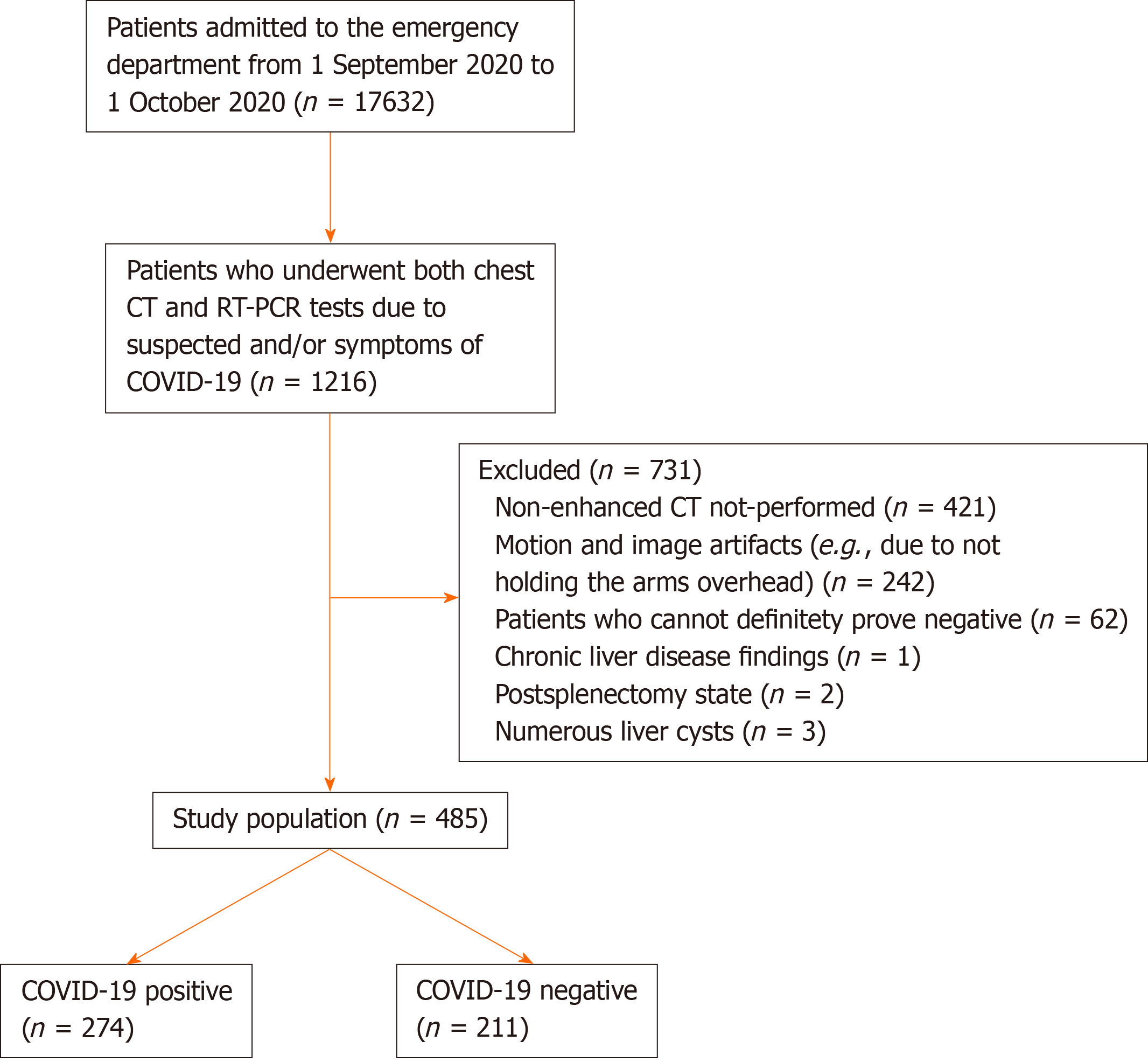

Between September 1, 2020 and October 1, 2020, 1216 patients who were admitted to the emergency department of our hospital with the suspicion and symptoms of COVID-19 and underwent both chest CT and the reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test were retrospectively evaluated. Patients with motion and image artifacts (e.g., due to not holding the arms overhead), those with chronic liver disease findings, and those without nonenhanced CT images, which would affect the density of the liver, were excluded from the study.

Patients with a positive RT-PCR test and involvement compatible with COVID-19 on CT following the proposed reporting criteria for CT findings related to COVID-19 by the Radiological Society of North America[11] were included in the COVID-19-positive group. Those who were negative for the RT-PCR test and had no lung lesions on CT were included in the control group. To avoid possible false negative and false positive results associated with the PCR test, we used both CT and RT-PCR results when creating the control and COVID-19-positive groups. We also checked all chest CT images of the patients, as there may have been early false negative RT-PCR results. Those with CT findings that were typical, atypical, or indeterminate were excluded, and the remaining patients were considered ‘’negative’’. According to these criteria, 62 patients were excluded from the control group. As a result, the study included a total of 485 consecutive presentations, of which 274 were COVID-19-positive (chest CT- and RT-PCR-positive) and 211 were COVID-19-negative controls (chest CT- and RT-PCR-negative). The flow diagram of the study population selection is shown in Figure 1.

The chest CT scan was performed in all patients with a 16-detector multi-slice CT device (Siemens Healthineers; Erlangen, Germany). The CT room and scanner were sanitized using standard cleaning procedures and approved disinfectants after each procedure. CT images were obtained at end inspiration during a single breath-hold without using intravenous contrast material. The main scanning parameters were: Tube voltage, 120 kV; tube current-time product, 50-350 mAs; pitch, 1.25; matrix, 512 × 512; slice thickness, 10 mm; and reconstructed slice thickness, 0.625-1.250 mm.

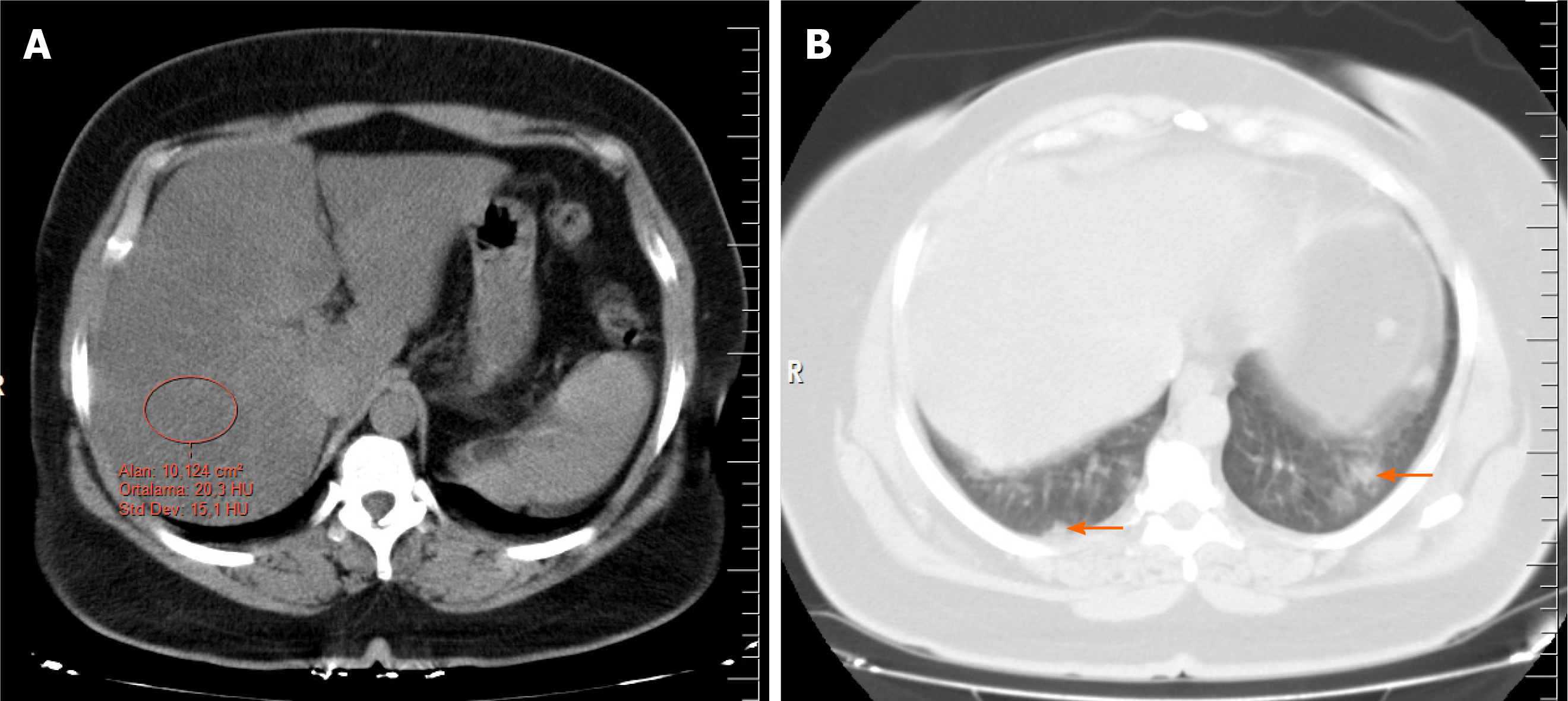

Several methods have been described in the literature to determine hepatic steatosis on noncontrast CT, including a liver attenuation value of 10 Hounsfield units (HU) that was less than the spleen attenuation, absolute liver attenuation of < 40 HU, and a liver-to-spleen attenuation ratio of < 1. For steatosis, unenhanced CT has a sensitivity ranging from 43% to 95% and a specificity of 90%-100%[12,13]. In this study, two radiologists reviewed the CT images and obtained the HU attenuation values of the liver using circular regions of interest with an area of approximately 10 cm2. The measurements were made at the level of the porta hepatis, avoiding the right hepatic lobe (segments 6 and 7), as well as vessels, calcifications, and biliary structures when possible (Figure 2). The chest CT images were evaluated by two thoracic radiologists with 8 and 9 yr of experience. They agreed on the results of each measurement and were blinded to the patient information. To prevent bias, the CT images were evaluated for steatosis in the abdominal window before the result of the RT-PCR test was known. Then, the lung window, with a center of −500 HU and a width of 1500 HU was examined for COVID-19 involvement. The RT-PCR test results were recorded after all the CT images were evaluated.

In this study, the definition of hepatic steatosis was accepted as a liver attenuation value of < 40 HU. Spleen attenuation values were not measured as the detection of steatosis by comparing the attenuation of the liver and spleen is more complex, requires more effort and time, and does not contribute to the diagnosis. All measurements were performed from a single section using the same method, which is supported by previous data showing that fat deposition in the liver is relatively homogeneous and most of the variation in the measurement of attenuation in that organ can be captured by measuring it in just one slice[14].

The COVID-19 pneumonia severity score (PSS), a semiquantitative method employed in previous studies, was used to measure the severity of lesions on chest CT[15,16]. First, the scope of the lesions in each lobe was estimated, and a score of 0 (none), 1 (affecting less than 5% of the lobe), 2 (affecting 5%-25% of the lobe), 3 (affecting 26%-49% of the lobe), 4 (affecting 50%-75% of the lobe), or 5 (affecting more than 75% of the lobe) was assigned. Second, the CT score was obtained by adding up the scores of the five lobes. For each patient, the CT score was in the range of 0 to 25.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Variables were divided into two groups, categorical and continuous. Frequency (percentage) values were used to report categorical variables, which were compared using the χ2 test. means ± SD were used to compare continuous variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine whether continuous data were normally distributed. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test, and continuous variables without normal distribution were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Statistical significance was defined as a P value of < 0.05 for all comparisons. Binominal logistic regression analysis was performed with significant variables. Spearman’s correlation was used to evaluate the relationships between continuous variables.

Of the 485 participants included in the study, 56.5% (n = 274) were included in the COVID-19-positive group and 43.5% (n = 211) in the control group. There was no significant difference between the COVID-19-positive and control groups in gender distribution (52.6% male, 47.4% female in the COVID-19-positive group and 53.6% male, 46.4% female in the control group; P = 0.450). The average age of the COVID-19-positive group was significantly higher than that of the control group (50.9 ± 10.9 years vs 40.4 ± 12.3 years, P < 0.001). The frequency of accompanying hepatic steatosis in the COVID-19-positive group was significantly higher compared with the control group (40.9% vs 19.4%, P < 0.001). The average hepatic attenuation value was significantly lower in the COVID-19-positive group compared with the control group (45.7 ± 11.4 HU vs 53.9 ± 15.9 HU, P < 0.001). The average PSS value of the COVID-19-positive group was 7.5 ± 3.4 (range: 2-18). The numbers of patients with obesity, overweight, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension were significantly higher in the COVID-19-positive group compared than in the control group (P = 0.001, P < 0.001, P = 0.003, and P < 0.001 respectively; Table 1).

| COVID-19+, n = 274 (56.5%) | COVID-19−, n = 211 (43.5%) | Total, n = 485 | P value | ||

| Age (yr) | 50.9 ± 10.9 | 40.4 ± 12.3 | 46.4 ± 12.7 | < 0.001c | |

| Male gender, n (%) | 144 (52.6) | 113 (53.6) | 257 (53.0) | 0.450 | |

| Hepatic steatosis, n (%) | Presence | 112 (40.9) | 41 (19.4) | 153 (31.5) | < 0.001c |

| Absence | 162 (58.1) | 170 (80.6) | 332 (68.5) | ||

| Liver's attenuation (HU) | 45.7 ± 11.4 | 53.9 ± 15.9 | 49.3 ± 14.2 | < 0.001c | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 45 (16.4) | 13 (6.2) | 58 (12.0) | 0.001b | |

| Overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) | 153 (55.8) | 55 (26.1) | 208 (42.9) | < 0.001c | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 68 (24.8) | 29 (13.7) | 97 (20.0) | 0.003b | |

| Hypertension | 107 (39.1) | 37 (17.5) | 144 (29.7) | < 0.001c | |

| Cardiac disease | 36 (13.1) | 23 (10.9) | 59 (12.2) | 0.455 | |

| Chronic lung disease | 29 (10.6) | 24 (13.7) | 53 (10.9) | 0.896 | |

| No comorbidity1 | 136 (49.6) | 129 (61.1) | 265 (54.6) | 0.012a | |

| Smoking history | 57 (20.8) | 56 (26.1) | 112 (23.1) | 0.110 | |

| Alcohol usage | 4 (1.5) | 4 (1.9) | 8 (1.6) | 0.709 | |

Logistic regression analysis (Table 2) showed that after adjusting for age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight, and obesity there odds of hepatic steatosis was nearly 2.2 times greater in the COVID-19 positive group compared with the controls [odds ratio (OR) 2.187; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.336-3.580, P < 0.001].

The characteristics of COVID-19 patients with and without the presence of hepatic steatosis are shown in Table 3. PSS was significantly higher in COVID-19 patients with hepatic steatosis than it was in those without steatosis (8.6 ± 3.5 vs 6.8 ± 3.2, P < 0.001). Similarly, obesity (25.0% vs 10.5%, P = 0.001), overweight (61.6% vs 40.6%, P < 0.001) and alcohol usage (3.6% vs 0%, P = 0.015) were significantly higher in those with hepatic steatosis.

| Variable | Steatosis+, n = 112 | Steatosis−, n = 162 | Total, n = 284 | P value |

| Age (yr) | 51.2 ± 9.2 | 50.7 ± 10.1 | 50.9 ± 10.9 | 0.321 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 65 (58.0) | 79 (48.8) | 144 (52.6) | 0.131 |

| Liver's attenuation, Hounsfield unit | 34.2 ± 4.8 | 53.6 ± 7.2 | 45.7 ± 11.5 | < 0.001c |

| Pneumonia severity score | 8.6 ± 3.5 | 6.8 ± 3.2 | 7.5 ± 3.4 | < 0.001c |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 28 (25.0) | 17 (10.5) | 45 (16.4) | 0.001b |

| Overweight (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2) | 69 (61.6) | 65 (40.6) | 134 (48.9) | < 0.001c |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (29.5) | 35 (21.6) | 68 (24.8) | 0.139 |

| Hypertension | 42 (37.5) | 65 (40.1) | 107 (39.1) | 0.662 |

| Cardiac disease | 13 (11.6) | 23 (14.2) | 36 (13.1) | 0.533 |

| Chronic lung disease | 12 (10.7) | 18 (11.1) | 30 (10.9) | 0.918 |

| No comorbidity1 | 54 (48.2) | 82 (50.6) | 136 (49.6) | 0.696 |

| Smoking history | 18 (16.1) | 39 (24.1) | 57 (20.8) | 0.109 |

| Alcohol usage | 4 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.5) | 0.015a |

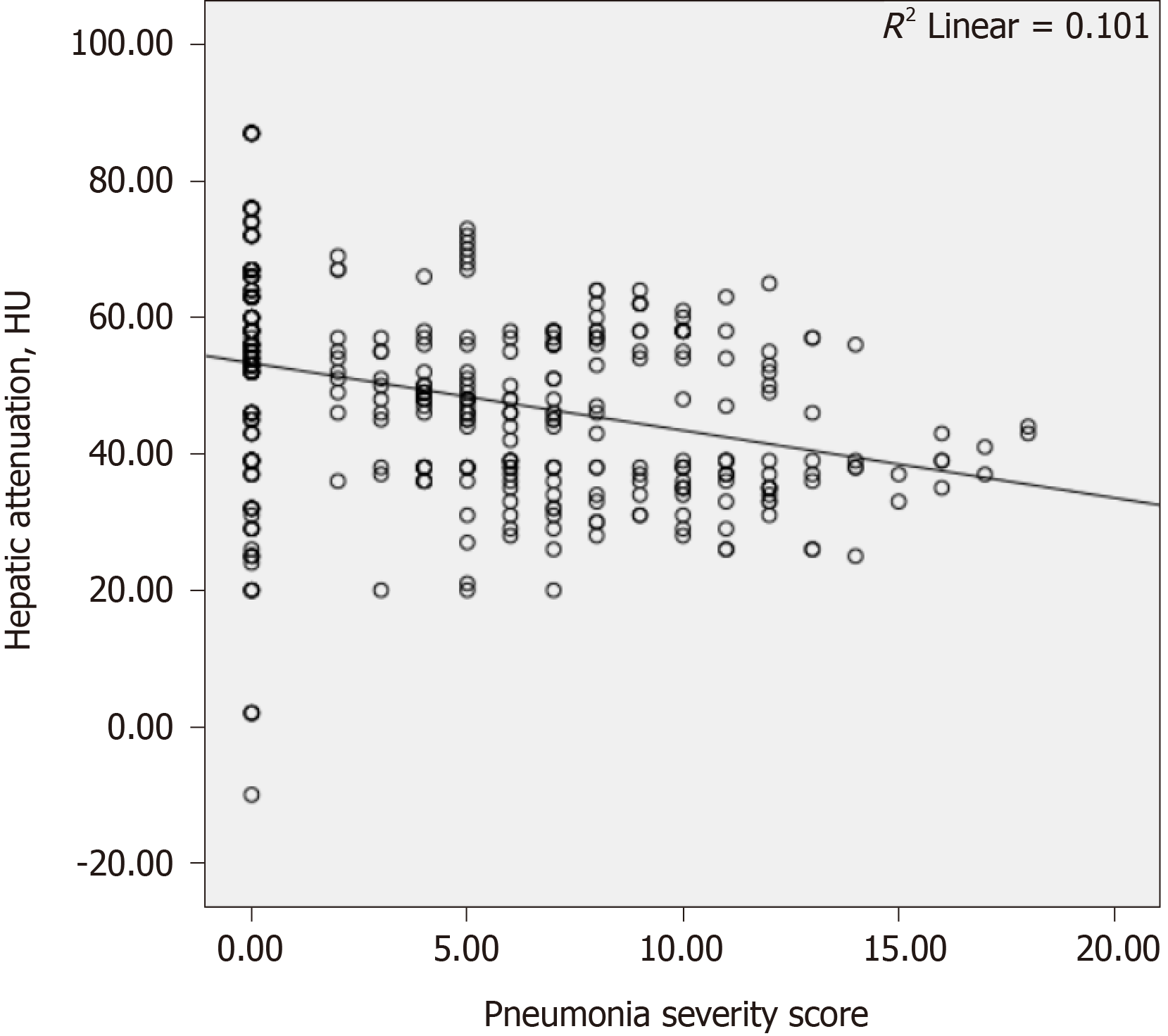

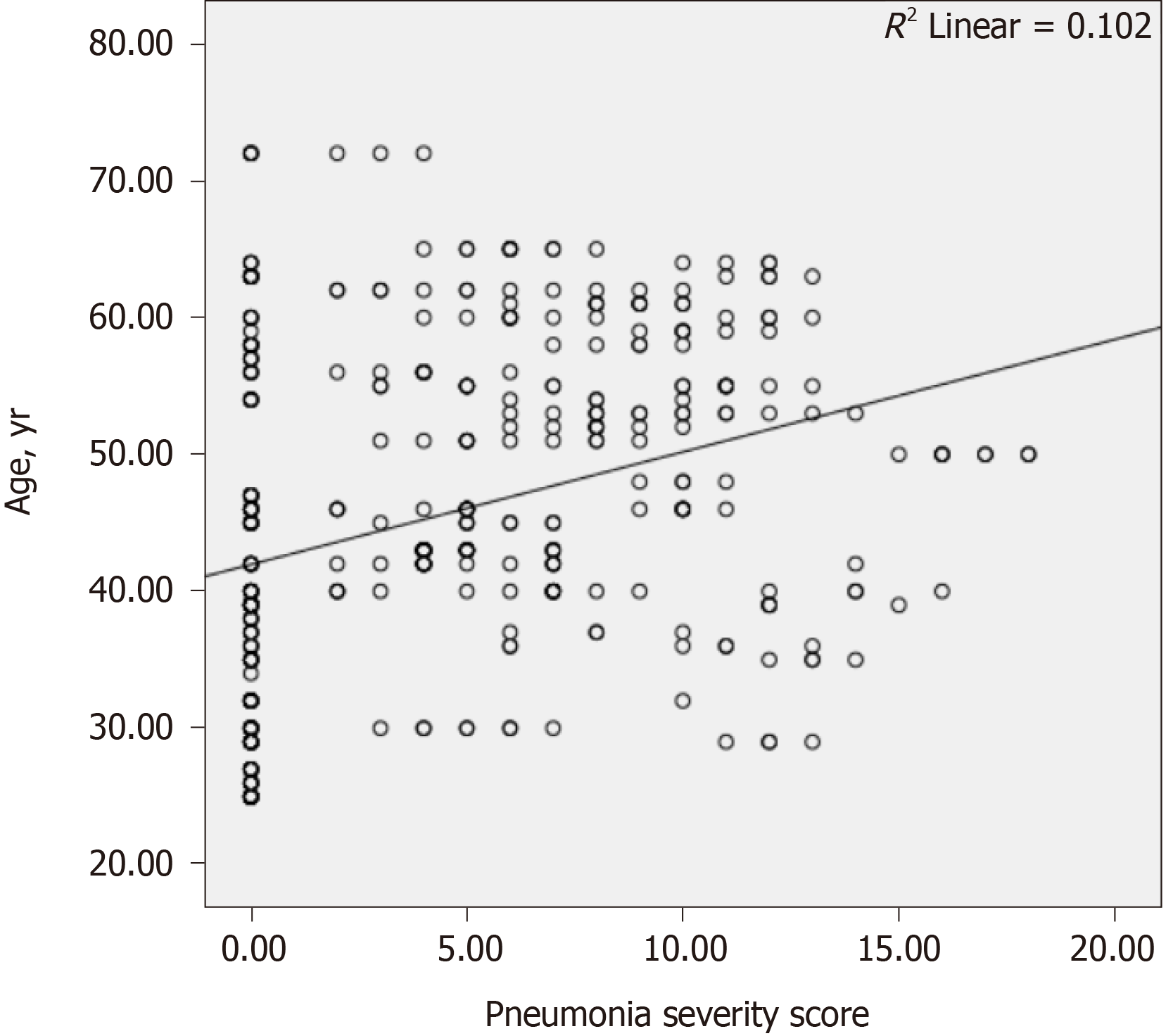

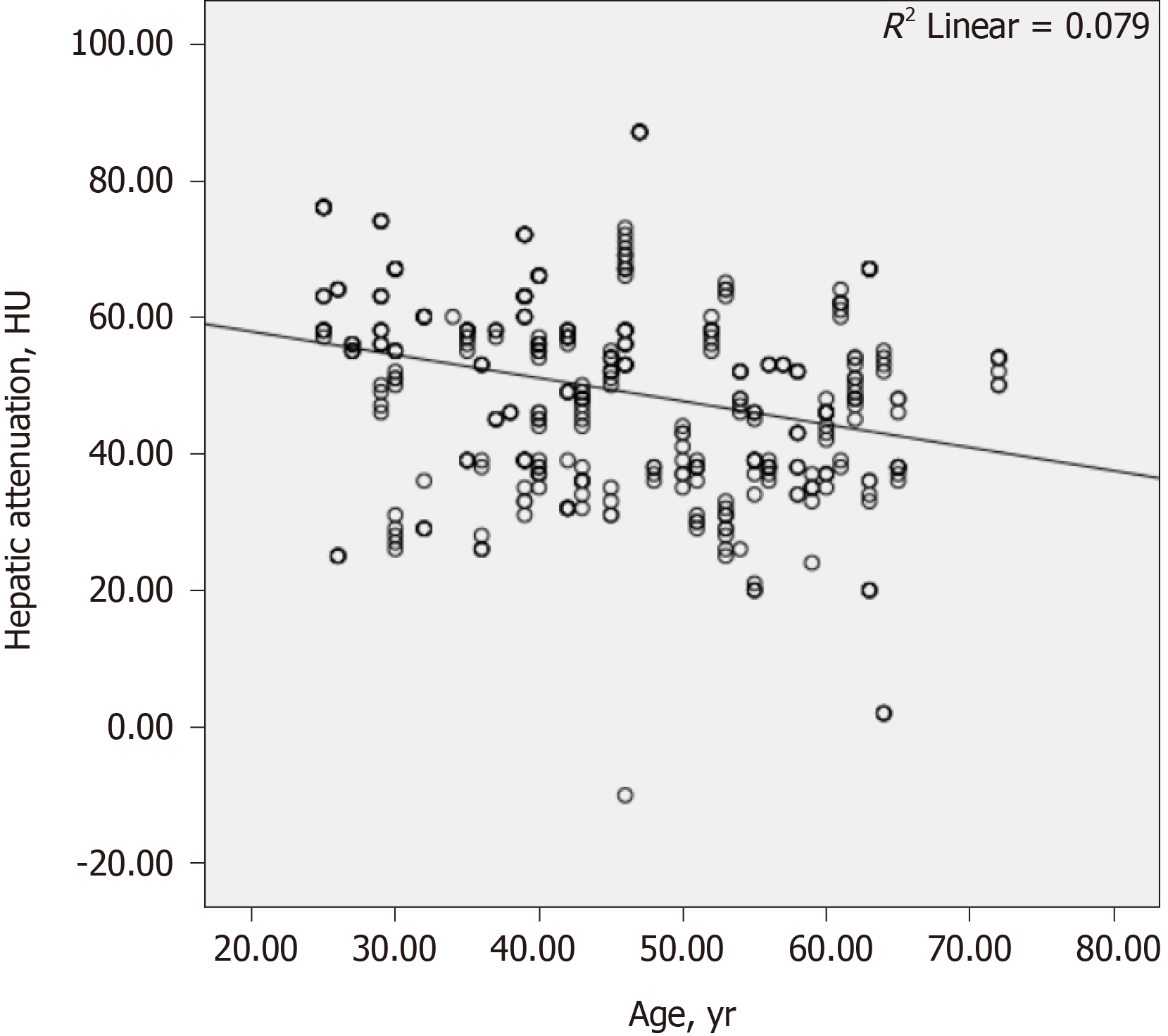

The results of the correlation analyses are shown in Table 4. There was a weakly negative correlation between the hepatic attenuation value and PSS (r = −0.305, P < 0.001; Figure 3). There was a weakly positive correlation between PSS and age (r = 0.329, P < 0.001; Figure 4), and a weakly negative correlation was found between hepatic attenuation and age (r = −0.242, P < 0.001; Figure 5).

Following studies revealing the relationship between obesity and COVID-19[5,7], researchers focused on more specific issues related to metabolic disorders. A study suggested a possible association between hepatic steatosis and COVID-19 infection and showed that the frequency of this liver disorder was increased in COVID-19-positive patients[9]. That study, conducted in Brazil, included 316 patients (204 RT-PCR-positive; 112 RT-PCR-negative and chest CT-negative) who were evaluated retrospectively, the frequency of hepatic steatosis was found to be higher in the RT-PCR-positive group compared to the control group (31.9% vs 7.1%, P < 0.001)[9]. In this study, the CT results of 485 people (274 RT-PCR- and CT-positive and 211 RT-PCR- and CT-negative), also found a significantly higher frequency of hepatic steatosis in the COVID-19 group than in the control group [40.9% (112 of 274 patients) vs 19.4% (41 of 211 patients)]. In the previous study, the COVID-19-positive group had an almost 4.7 times higher probability of steatosis (OR: 4.698) compared with the controls. In our study, the odds were approximately 2.2 higher (OR: 2.187). The difference might be related to the greater prevalence of hepatic steatosis in Turkey. Unlike the Brazilian study, we evaluated comorbidities such as obesity, overweight, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. The results of our study revealed that the incidence of hepatic steatosis remained increased in COVID-19 patients even after adjustment for age and comorbidities. In addition, in our study, the rates of hepatic steatosis in both the COVID-19 and control groups were higher than those of the Brazilian study, which may be related to nutritional, genetic or other regional differences. The prevalence of NAFLD worldwide is estimated to be approximately 25%[17]. In a 2016 study conducted in Brazil in an age group similar to our study, a total of 800 people (561 women and 239 men) were examined, and the prevalence of steatosis was found to be 29.1% and higher in men than in women[18]. According to 2016 data published by WHO, Turkey is the country with the highest obesity prevalence (32.1%) in Europe[17]. A comprehensive review published in 2019, included studies reporting that the NAFLD prevalence in Turkey was between 47.9% and 54.4% in age groups similar to those in our study[17]. In a previous study conducted in our hospital population, it was found that men were most affected by NAFLD in the third and fourth decades of age[19]. Despite early studies reporting a higher risk of NAFLD in women, a large body of evidence now shows that the prevalence of NAFLD is higher in men than women, with gender-specific differences by age[20].

A systematic literature review of the association between NAFLD and severe COVID-19 regardless of obesity, which is considered the most important risk factor for both NAFLD and COVID-19, concluded that NAFLD might be a determining factor for severe COVID-19 even after adjusting for the presence of obesity (OR: 2.358, P < 0.001)[5]. However, a direct comparison and correlation analysis between hepatic steatosis and disease severity has not previously been published. In patients with COVID-19 requiring intensive care, new parameters such as invasive mechanical ventilation, nosocomial infections, acute respiratory distress syndrome, coagulopathy, and acute kidney injury are added to the main comorbidities, including male gender, advanced age, hypertension, coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, and chronic kidney disease, which further complicates the investigation of factors affecting disease progression[7,21,22]. In this study, we examined the relationship between PSS and hepatic steatosis in patients with symptomatic infection. We found that the PSS was significantly increased in COVID-19 patients with hepatic steatosis (8.6 ± 3.5 vs 6.8 ± 3.2, P < 0.001). That may indicate that comorbidities may accompany in patients with severe pneumonia. In addition, we showed a moderate correlation between hepatic steatosis with age and PSS. We consider that our results are the first data to directly demonstrate that relationship.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, having a chronic liver disease such as alcohol-related liver disease, NAFLD, and especially cirrhosis, can increase the risk of severe COVID-19[23]. In a retrospective study conducted in China including 202 COVID-19 patients, the prevalence of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) was 37.6%, and the risk of disease progression was increased in that group[24]. Various articles attempting to explain that possible relationship emphasize that MAFLD (defined as NAFLD in some articles) is a liver symptom of metabolic syndrome, is associated with chronic inflammation, and contributes to the interaction in the cytokine storm described in COVID-19 patients, causing disease progression, complications, and fatal consequences[9,10,24]. In support of those studies, we found that the radiological severity of pneumonia was higher in COVID-19 patients with steatosis that without steatosis. Our study, which investigated the relationship between hepatic steatosis and the severity of COVID-19 disease in patients according to tomographic criteria, provides valuable data to guide further study.

This study had several limitations. It was conducted retrospectively in a single tertiary university hospital, and all patients were from a single geographic region. The prevalence of hepatic steatosis may differ in different populations and regions. A strength of our study, is that to the best of our knowledge, it is the first to investigate the relationship between CT-assessed steatosis and PSS in adult COVID-19 patients.

The current study revealed a significantly higher prevalence of hepatic steatosis on CT in COVID-19 patients compared with controls after adjustment for age and comorbidities. In addition, it found a correlation between the severity of pneumonia measured on CT and liver density. Therefore, liver density measurement can be considered as a new parameter in the risk analysis of infected patients. This evaluation can be quickly and easily performed using already available CT data without the need for an additional examination. Further study is needed to confirm the presence of such an association after considering and minimizing multiple variables that can affect hepatic steatosis.

Recent studies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) demonstrated that obesity is significantly associated with increased disease severity, clinical outcome, and mortality.

The association between hepatic steatosis, which frequently accompanies obesity, the pneumonia severity score (PSS) evaluated by computed tomography (CT), and the prevalence of steatosis in patients with COVID-19 remains to be elucidated.

The study objective was to assess the frequency of hepatic steatosis in the chest CT of COVID-19 patients and its association with the PSS.

This was a retrospective study evaluating the CT of COVID-19 positive and negative patients in a tertiary hospital.

Of the 485 patients, 274 (56.5%) were defined as the COVID-19-positive group and 211 (43.5%) as the control group. The frequency of hepatic steatosis was significantly higher in the positive group than in the control group (40.9% vs 19.4%, P < 0.001). The average hepatic attenuation values were significantly lower in the positive group than in the control group (45.7 ± 11.4 HU vs 53.9 ± 15.9 HU, P < 0.001). Logistic regression analysis showed that after adjusting for age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, overweight, and obesity there was almost a 2.2 times greater odds of hepatic steatosis in the COVID-19-positive group than in the controls (odds ratio 2.187; 95% confidence interval: 1.336-3.580, P < 0.001).

The current study revealed a significantly higher prevalence of hepatic steatosis on CT in COVID-19 patients compared with controls after adjusting for age and comorbidities.

Liver density and PSS can be easily examined on CT images of COVID-19 patients and the relationship between tomographic severity and steatosis can be evaluated.

| 1. | Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35178] [Cited by in RCA: 30484] [Article Influence: 5080.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 2. | Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5202] [Cited by in RCA: 4710] [Article Influence: 785.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 3. | Sarı O, Hosbul T, Sahiner F. Basic Epidemiological Parameters at the end of the 5th month of the COVID-19 Outbreak. J Mol Virol Immunol. 2020;1:67-80. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2021 [cited 2 January 2021]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. |

| 5. | Hussain A, Mahawar K, Xia Z, Yang W, El-Hasani S. Obesity and mortality of COVID-19. Meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14:295-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sümbül HE, Sahiner F. Rapid Spreading of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Risk Factors: Epidemiological, Immunological and Virological Aspects. J Mol Virol Immunol. 2020;1:36-50. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lavie CJ, Sanchis-Gomar F, Henry BM, Lippi G. COVID-19 and obesity: links and risks. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2020;15:215-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cunningham JW, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Jering KS, Bhatt AS, Rosenthal N, Solomon SD. Clinical Outcomes in Young US Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Medeiros AK, Barbisan CC, Cruz IR, de Araújo EM, Libânio BB, Albuquerque KS, Torres US. Higher frequency of hepatic steatosis at CT among COVID-19-positive patients. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45:2748-2754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sachdeva S, Khandait H, Kopel J, Aloysius MM, Desai R, Goyal H. NAFLD and COVID-19: a Pooled Analysis. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Simpson S, Kay FU, Abbara S, Bhalla S, Chung JH, Chung M, Henry TS, Kanne JP, Kligerman S, Ko JP, Litt H. Radiological Society of North America Expert Consensus Statement on Reporting Chest CT Findings Related to COVID-19. Endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the American College of Radiology, and RSNA - Secondary Publication. J Thorac Imaging. 2020;35:219-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 441] [Cited by in RCA: 567] [Article Influence: 94.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Lawrence DA, Oliva IB, Israel GM. Detection of hepatic steatosis on contrast-enhanced CT images: diagnostic accuracy of identification of areas of presumed focal fatty sparing. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:44-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dendl LM, Schreyer AG. Steatosis hepatis--eine Herausforderung? Radiologe. 2012;52:745-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Speliotes EK, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Foster MC, Sahani DV, Hirschhorn JN, O'Donnell CJ, Fox CS. Liver fat is reproducibly measured using computed tomography in the Framingham Heart Study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:894-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou Z, Guo D, Li C, Fang Z, Chen L, Yang R, Li X, Zeng W. Coronavirus disease 2019: initial chest CT findings. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:4398-4406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ooi GC, Khong PL, Müller NL, Yiu WC, Zhou LJ, Ho JC, Lam B, Nicolaou S, Tsang KW. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: temporal lung changes at thin-section CT in 30 patients. Radiology. 2004;230:836-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kaya E, Yılmaz Y. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A growing public health problem in Turkey. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30:865-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cruz JF, Cruz MA, Machado Neto J, de Santana DS, Oliveira CC, Lima SO. Prevalence and sonographic changes compatible with fatty liver disease in patients referred for abdominal ultrasound examination in Aracaju, SE. Radiol Bras. 2016;49:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bahcecioglu IH, Koruk M, Yilmaz O, Bolukbas C, Bolukbas F, Tuncer I, Ataseven H, Yalcin K, Ozercan IH. Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the East-Southeastern Anatolia regions in Turkey. Med Princ Pract. 2006;15:62-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ballestri S, Nascimbeni F, Baldelli E, Marrazzo A, Romagnoli D, Lonardo A. NAFLD as a Sexual Dimorphic Disease: Role of Gender and Reproductive Status in the Development and Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Inherent Cardiovascular Risk. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1291-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 411] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gao Y. COVID-19: Risk factors for critical illness. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim L, Garg S, O'Halloran A, Whitaker M, Pham H, Anderson EJ, Armistead I, Bennett NM, Billing L, Como-Sabetti K, Hill M, Kim S, Monroe ML, Muse A, Reingold AL, Schaffner W, Sutton M, Talbot HK, Torres SM, Yousey-Hindes K, Holstein R, Cummings C, Brammer L, Hall AJ, Fry AM, Langley GE. Risk Factors for Intensive Care Unit Admission and In-hospital Mortality among Hospitalized Adults Identified through the U.S. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET). Clin Infect Dis. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease); People with Certain Medical Conditions. 2021. [cited 4 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. |

| 24. | Ji D, Qin E, Xu J, Zhang D, Cheng G, Wang Y, Lau G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective study. J Hepatol. 2020;73:451-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 68.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Turkish Society of Radiology; and Turkish Society of Interventional Radiology.

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country/Territory of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Alberca RW, Bork U, Tai DI S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH