Published online May 8, 2017. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v6.i2.124

Peer-review started: September 20, 2016

First decision: October 28, 2016

Revised: December 4, 2016

Accepted: January 11, 2017

Article in press: January 14, 2017

Published online: May 8, 2017

Processing time: 231 Days and 14.9 Hours

To explore and to analyze the patterns in decision-making by pediatric gastroenterologists in managing a child with a suspected diagnosis of functional gallbladder disorder (FGBD).

The questionnaire survey included a case history with right upper quadrant pain and was sent to pediatric gastroenterologists worldwide via an internet list server called the PEDGI Bulletin Board.

Differences in decision-making among respondents in managing this case were observed at each level of investigations and management. Cholecystokinin-scintigraphy scan (CCK-CS) was the most common investigation followed by an endoscopy. A proton pump inhibitor was most commonly prescribed treating the condition. The majority of respondents considered a referral for a surgical evaluation when CCK-CS showed a decreased gallbladder ejection fraction (GBEF) value with biliary-type pain during CCK injection.

CCK infusion rate in CCK-CS-CS and GBEF cut-off limits were inconsistent throughout practices. The criteria for a referral to a surgeon were not uniform from one practitioner to another. A multidisciplinary team approach with pediatric gastroenterologists and surgeons is required guide the decision-making managing a child with suspected FGBD.

Core tip: Functional gallbladder disorder (FGBD) is a common motility disorder of the gallbladder that results in abdominal pain and cholecystectomy in children. The guideline for managing children with FGBD is lacking. The questionnaire survey is a pilot study performed by pediatric gastroenterologists worldwide via the PEDGI Bulletin Board. Differences in decision-making among respondents in managing this case were observed at each level of investigations and management. Since, a different risk-benefit ratio should be considered in children with suspected FGBD. The authors include an algorithm for the approach in managing children with suspected FGBD based on literature review.

- Citation: Nakayuenyongsuk W, Choudry H, Yeung KA, Karnsakul W. Decision-making patterns in managing children with suspected biliary dyskinesia. World J Clin Pediatr 2017; 6(2): 124-131

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v6/i2/124.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v6.i2.124

Functional gallbladder disorder (FGBD) is a motility disorder of the gallbladder that results in decreased contractility of the gallbladder and colicky pain in the epigastrium and/or the right upper quadrant of the abdomen (RUQ). FGBD was previously called chronic acalculous cholecystitis, acalculous cholecystitis, or biliary dyskinesia and is a diagnosis of exclusion. Therefore further investigations are routinely performed to exclude other hepatobiliary or gastrointestinal diseases. Experts’ consensus developed the Rome III criteria in 2006[1] to help guide the management of FGBD. A child who is suspected to have FGBD must experience recurrent episodes of the abdominal pain which last longer than 30 min without relief after bowel movements, postural changes or antacids. The child must have normal liver enzymes, conjugated bilirubin, and amylase/lipase. In addition, the gallbladder must be present and other structural diseases must be excluded. Supportive criteria include the presence of nausea and vomiting, classic biliary pain at RUQ that radiates to the back and/or right infra subscapular region, and pain disturbing sleep[1].

The cholecystokinin-scintigraphy scan (CCK-CS) is generally recommended as a part of the diagnosis for FGBD. The test reports a cut-off value of a gallbladder ejection fraction (GBEF) The cut-off limits that are < 40% suggest the diagnosis of FGBD. FGBD is frequently diagnosed in children with an increase in the number of cholecystectomies performed over the past two decades[2-8]. Several children with a diagnosis of FGBD, however, did not improve their pain symptoms after cholecystectomy[2-8]. The study involves a questionnaire based survey delivered to pediatric gastroenterologist members via the PEDGI Bulletin Board, the internet list server. The objective of the study was to explore and to analyze the patterns in decision-making by pediatric gastroenterologists in managing a child with a suspected diagnosis of FGBD.

This is a questionnaire-based survey distributed to the PEDGI Bulletin Board accessible by hundreds of pediatric gastroenterologists worldwide. The PEDGI Bulletin Board is the internet list server that encourages pediatric gastroenterologists and hepatologists worldwide to communicate with one another electronically. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. At the beginning of the questionnaire introduced to the GI bulletin board, only practicing pediatric gastroenterologists (not trainees) were requested and consented themselves to perform the questionnaire. The survey data were collected from the participating PEDGI Bulletin Board users who used the network from January 2011 to April 2011. The survey was completed and analyzed using an Internet-based questionnaire (SurveyMonkey.com, Portland, Oregon, United States). The questionnaire was designed to have participants complete within 10 min.

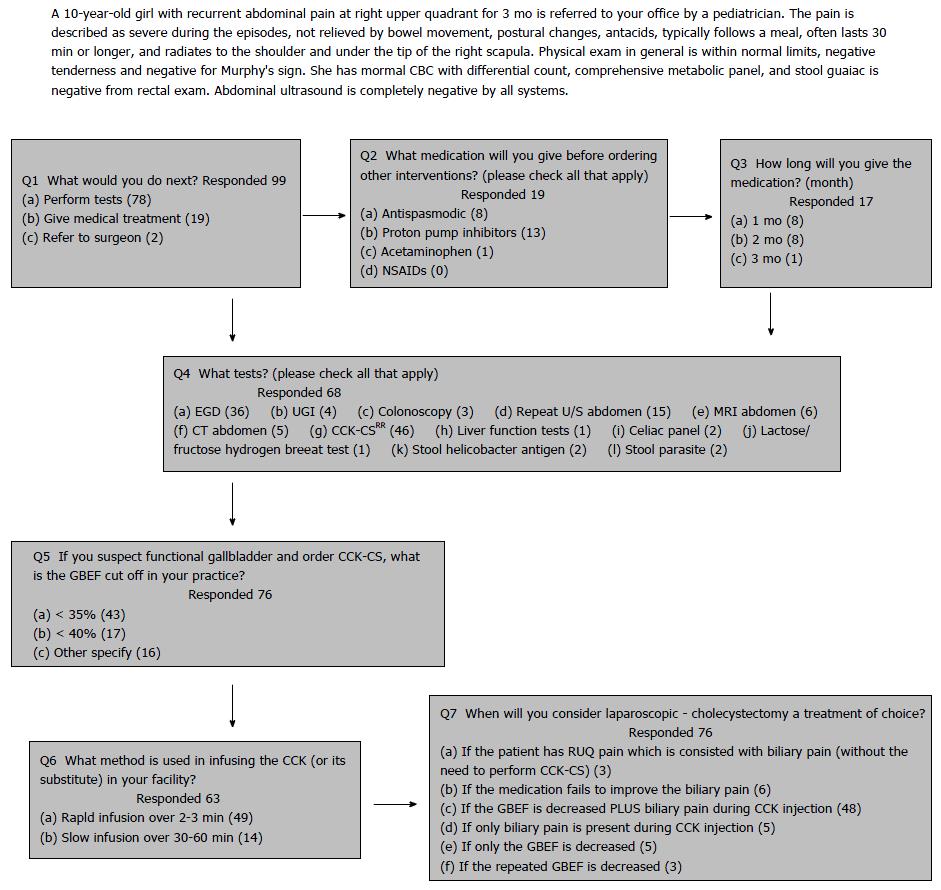

The survey includes a case history with right upper quadrant pain in Figure 1. The questionnaire consists of 7 questions (Q1-7) in order to observe the patterns of decision-making in managing the case (Figure 1). Q1 gives a direction at the initial step whether the patient should have a test or a medical or surgical treatment performed first. Q2-3 is specifically addressed to the types and the duration of such medical treatments. Q4 is related to the decision-making patterns in investigations. Q5-7 is for their criteria for the CCK-CS and GBEF cut-off limits in diagnosing FGBD and the surgical treatment of FGBD.

The questionnaire survey consisted of 7 questions. One hundred pediatric gastroenterologists participated in the questionnaire study. Of these 100 respondents, 99 completed all questions in the survey, and 71 informed the location of their practices (60 in the United States and 11 from non-United States countries). For Q1 and 2, 19 respondents (19%) decided to treat the abdominal pain with the medical treatment first. Of these 19 respondents, 13 (68.4%) selected proton pump inhibitors (PPI), 8 (42.1%) for antispasmodics, 1 (5.3%) for acetaminophen, 2 for histamine 2 receptor antagonists, 1 for probiotic, 1 for cyproheptadine as their choices of the treatment. In Q3, 17 respondents answered the duration of such a medical treatment. Interestingly, 2 respondents in Q1 referred the patient to a surgeon without further investigations or a treatment trial.

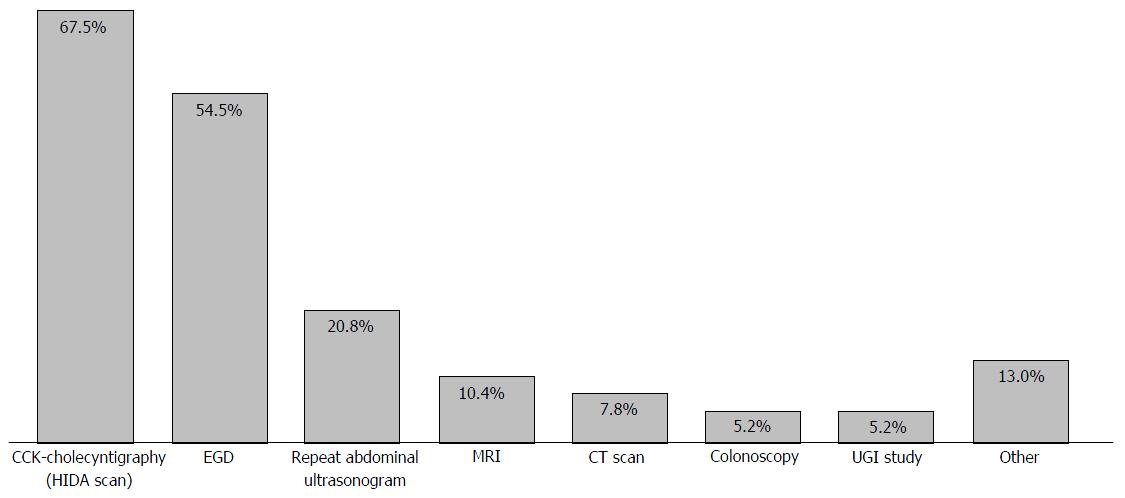

Figure 2 demonstrated the patterns in decision-making of the ordered investigations (Q4). CCK-CS (67.7%) and an upper endoscopy (52.9%) were the most commonly ordered tests. Q5-7 indicated the techniques used for CCK-CS and the criteria of GBEF cut-off limits used to diagnose FGBD and to refer to a surgeon for an evaluation for cholecystectomy at their institutions. Seventy-six respondents responded to Q6 and different GBEF cutoff limits were used, < 35% in 43 respondents (56.6%), < 40% in 17 respondents (22.4%), < 30% in 3 respondents, < 25% in 3 respondents, < 20% in one respondent, and < 15% in one respondent (Table 1). Four respondents did not know the GBEF cutoff limits at their institutions. Three respondents decided not to order or to avoid ordering the test, and one respondent did not have the test available at the institution.

| % GBEF used as cut-off | Responses1 |

| < 40% | 17 (20) |

| < 35% | 47 (55) |

| < 30% | 3 (3.5) |

| < 25% | 4 (4.7) |

| < 16% | 2 (2.4) |

| < 15% | 2 (2.4) |

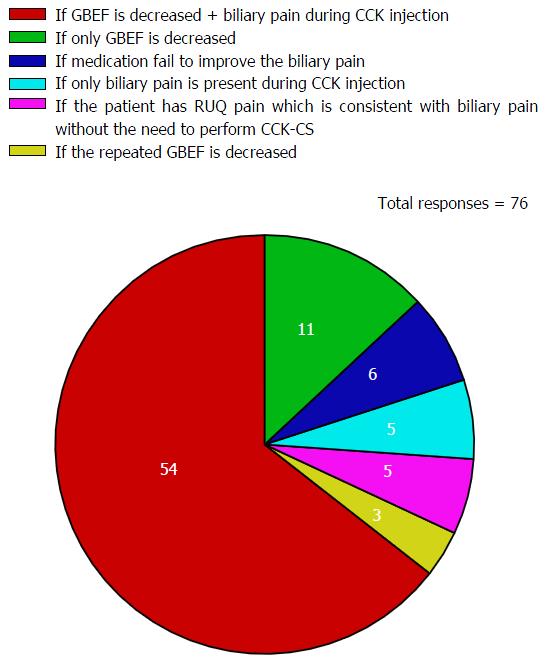

Sixty-three respondents responded to Q6. While 49 respondents (77.8%) selected CCK-CS with the rapid infusion of CCK over 2-3 min as the technique used at their institutions, 14 (22.2%) chose the CCK-CS technique with the slow infusion over 30-60 min. For Q7, the majority of respondents (64%) responded by referring the patient to a surgeon with the criteria when both the GBEF value was abnormal and similar types of abdominal pain was reproduced during the infusion of CCK (Figure 3).

Several GI diseases and biliary disorders share a similar type of abdominal pain. The presentation of this clinical vignette described in the questionnaire is consistent with FGBD defined by the ROME III criteria when all known causes of epigastric and/or RUQ pain are excluded[1]. The patterns in decision-making in managing the case throughout the questionnaire were quite heterogeneous. Interestingly, 2 respondents in Q1 referred the patient to a surgeon without investigations or any treatment trial. Our questionnaire survey demonstrated that only 19% of respondents prescribed PPI or histamine 2 antagonists as the first-line management before performing the tests. This is contrary to other studies which have documented that it is a common practice to empirically treat gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and acid peptic disease prior to extensive investigations in such a case when FGBD is suspected[1,9]. Few case reports described children with the diagnosis of FGBD who had a complete relief from the abdominal pain when a PPI was used[10,11].

Further investigations were preferred in the majority of the respondents. It is generally recommended that hepatic function panel (AST, ALT, serum total and direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase) amylase/lipase, and an abdominal ultrasound be performed first to exclude hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders[12,13]. Since these tests were already ordered and reported as normal in the clinical vignette, CCK-CS and an upper endoscopy were observed to be the most common tests chosen by respondents. Biopsies of the proximal GI tract are generally considered even in the absence of gross endoscopic findings as microscopic endoscopic findings may reveal features of eosinophilic gastritis, GERD, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, Crohn’s disease, and villus atrophy in those who were also diagnosed with FGBD[10,14,15] to look for mucosal disease that might explain symptoms or improve symptoms when treated. For example, Tutel’ian et al[16] reported chronic atrophic gastritis from H. pylori infection in patients who were diagnosed with FGBD prior to the endoscopy. A series of children with FGBD were later diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, hiatal hernia, and cyclic vomiting[16], and with esophagitis, H. pylori infection and duodenitis after cholecystectomy[17]. Children with functional constipation had a significant impairment of the gallbladder motility[18]. Colonoscopy is usually not required in the absence of lower abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, or hematochezia[14,15]. As such, an upper endoscopy is recommended to exclude any possible GI diseases which can cause epigastric and/or RUQ pain before a referral to a surgeon for cholecystectomy.

Currently there is no definite guideline in the pediatric practice regarding the appropriate technique performed for the CCK infusion rate and the GBEF cut-off limit in performing a CCK-CS study. The diversity of the techniques used for CCK-CS was observed not only from the questionnaire responses, but experts’ consensus such as ROME III committee and the Gastrointestinal Council of the Society of Nuclear Medicine. This 3-min rapid CCK infusion and the GBEF cut off limit of < 35% were most common choices in Q5 and Q6, respectively. This rapid infusion technique in theory can cause a severe degree of abdominal pain and nausea in even a healthy subject. This is explained by the fact that CCK slows down the gastric emptying[19,20]. According to the ROME III criteria a continuous intravenous CCK infusion over a 30-min period is preferred[1]. On the contrary, the new guidelines from the Gastrointestinal Council of the Society of Nuclear Medicine recommend the slow infusion rate of the CCK over 60 min as the standard test in adults since this technique generates a physiologic response for contraction of the gallbladder and discourage the evidence of the reproducible pain after the CCK injection during CCK-CS[19,21].

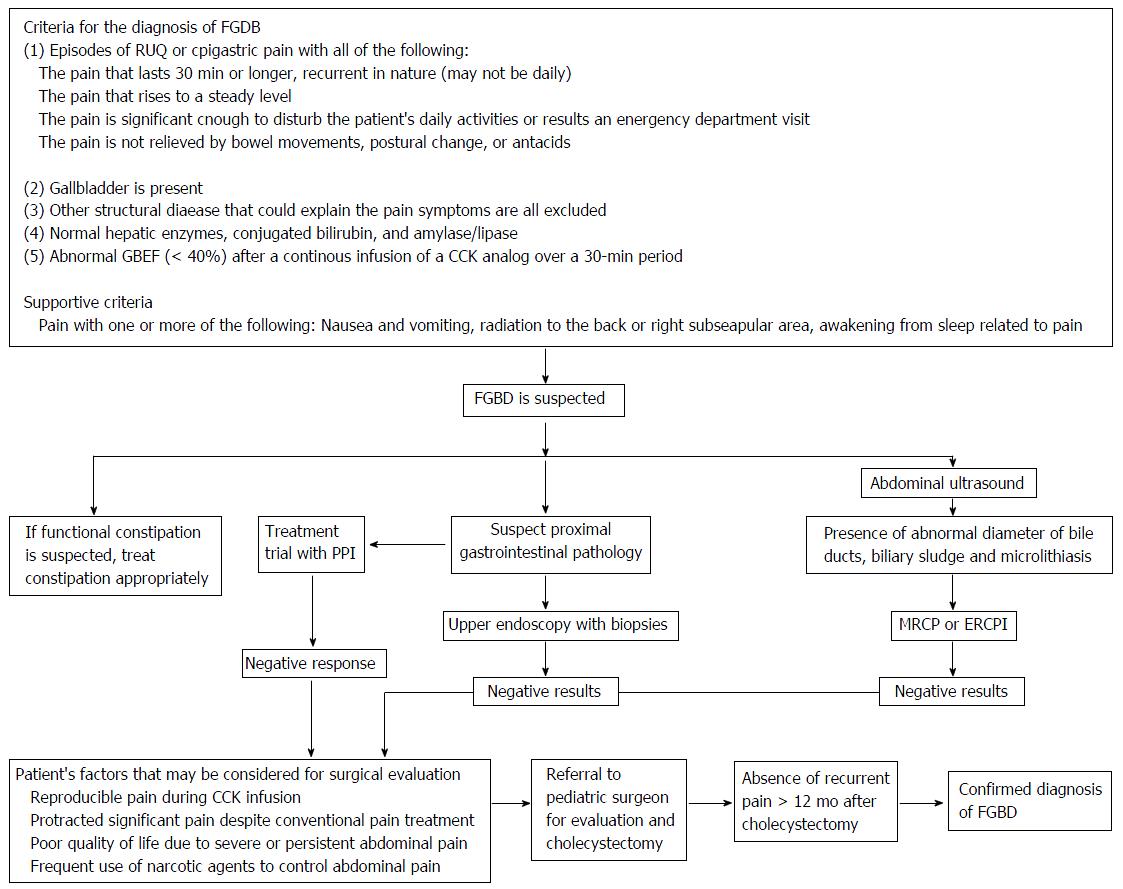

Table 1 demonstrates the difference in the GBEF cut-off limits used as the criteria to guide the management for the questionnaire respondents. The GBEF cut-off limits vary from 15%-40% in the reported literature depending on the CCK-CS techniques[22]. When GBEF cut-off limit < 35% was used as an indication for the surgery, the resolution of symptoms was more frequently observed after cholecystectomy in several studies[23]. The cut-off limit of < 15%, however, was a better predictor for a successful outcome after cholecystectomy with negative predictive value of 85%[8]. A CCK provocation test is even a better predictor for the resolution of symptoms than using GBEF cut-off limits alone after cholecystectomy[24]. Reproducible symptoms during the CCK stimulation predicted a symptom relief after cholecystectomy[25,26]. Lyons et al[27] reported that 44 children with a stringent GBEF cut-off limit at < 11% had the resolution of symptoms after cholecystectomy. However, there was no observed correlation between with GBEF and the presence of gallbladder pathology such as cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, or cholesterolosis[28]. Interestingly Mahida et al[29] reported symptom improvement by 82% of 153 children with FGBD undergoing cholecystectomy regardless of their GBEF values. The number of children undergoing cholecystectomy has increased in the past decade[30]. Despite the safety of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children, a different risk-benefit ratio should be considered in children with suspected FGBD[31]. Figure 4 demonstrates the algorithm for the best practice management approach in children with suspected FGBD based on our literature review.

There are several limitations in the present study. The sample size was small. Since the survey was voluntary, the respondents were able to withdraw the participation of the questionnaire at any time. Although almost all respondents (99%) responded to Q1, the ambiguity of the question may attribute to the lower response rates in the subsequent questions. FGBD may not be the condition that respondents regularly treat and, therefore, up to one-third of respondents skipped questions without explanations or comments. For Q5-6, the information on the techniques and the cut-off limits of the CCK-CS used at their institutions may not have been available at the time they performed the questionnaire survey.

In our opinion, none of these diagnostic modalities are absolute for the diagnosis of FGBD. Ultimately the decision making for cholecystectomy should be individualized as some patients suffer from severe abdominal pain despite aggressive pain management (Figure 4). As many children who are diagnosed with FGBD may experience recurrent symptoms even after cholecystectomy, they often follow-up with pediatric gastroenterologists or pediatricians and do not have a follow-up with the surgeons who operate them. Therefore, we recommend them to continue to follow-up with both pediatric gastroenterologists and surgeons as a team approach that if no recurrent symptoms are observed within a year after cholecystectomy, the diagnosis of FDGB is confirmed.

The diversity in decision-making among pediatric gastroenterologist respondents in managing the child in this clinical vignette was observed at each step in the questionnaire. A decision for the referral for cholecystectomy should be carefully considered on an individual case basis. The consensus for the guideline in managing children with FGBD may require a team effort among pediatric gastroenterologists, nuclear medicine radiologists, and pediatric surgeons. A multicenter clinical trial study may be necessary to collect longitudinal data in children diagnosed with FGBD. This collaboration will likely shed light on the natural history and the outcome of FGBD in children.

The authors thank all the participants from the PEDGI bulletin board for completing the questionnaires and Robert Whinnery for the manuscript assistance.

The rates of cholecystectomy are rising in children with biliary dyskinesia or functional gallbladder disorder (FGBD). FGBD may be a cause of chronic abdominal pain in children and is a diagnosis of exclusion. Not all symptoms of FGBD disappeared after cholecystectomy. The cut-off limits of a gallbladder ejection fraction of the cholecystokinin-scintigraphy scan (CCK-CS) are the key to the diagnosis and the treatment of FGBD. This raises the issue of the accurate interpretation of the test and a thorough investigation to exclude other diseases which have symptoms like FGBD. The study was to explore discrepancy of decision making in managing a case, a scenario of which is consistent with FGBD.

FGBD is one of the challenging fields in pediatrics. Symptoms overlap with other gastrointestinal disorders such as functional dyspepsia. Limited knowledge in this field of FGBD in children is currently observed in the current medical literature for interpretation of safety and efficacy of the investigations and treatment. There is a need for consensus on symptoms defining and a test diagnosing FGBD. Children with suspected FGBD requires a team approach with primary care physicians, pediatric gastroenterologists and pediatric surgeons. A multicenter randomized controlled trial study comparing medical vs surgical management will shed more light to understand the natural history of FGBD. There are several limitations in the present study. The sample size was small. Since the survey was voluntary, the respondents were able to withdraw the participation of the questionnaire at any time. Although almost all respondents (99%) responded to Q1, the ambiguity of the question may attribute to the lower response rates in the subsequent questions. FGBD may not be the condition that respondents regularly treat and, therefore, up to one-third of respondents skipped questions without explanations or comments. For Q5-6, the information on the techniques and the cut-off limits of the CCK-CS used at their institutions may not have been available at the time they performed the questionnaire survey.

This is a pilot study using questionnaire-based survey distributed to the PEDGI Bulletin Board accessible by hundreds of pediatric gastroenterologists worldwide. The PEDGI Bulletin Board is the internet list server that encourages pediatric gastroenterologists and hepatologists worldwide to communicate with one another electronically. FGBD is a rare disease in children. A multicenter randomized controlled trial study comparing medical vs surgical management is possible and feasible through the collaborations of a broader network among primary care physicians, pediatric gastroenterologists and pediatric surgeons.

Based on the result from this study, there was diversity in decision-making among pediatric gastroenterologist respondents in managing the child in this clinical vignette was observed at each step in the questionnaire. A decision for the referral for cholecystectomy should be carefully considered on an individual case basis.

Other terminologies that may be used to describe FGBD include biliary dyskinesia or acalculous cholecystitis.

The authors have nicely summarized the problems clinicians face with the diagnosis and treatment of Functional Gallbladder Disorder. They have also proposed a guideline to help clinicians manage this condition. The publication will aid clinicians in their practice and hence should proceed. It does require minor revisions as it needs to be highlighted that cholecystectomy is ultimately a decision that needs to be made after thorough counseling of the family by the pediatric surgeon.

| 1. | Behar J, Corazziari E, Guelrud M, Hogan W, Sherman S, Toouli J. Functional gallbladder and sphincter of oddi disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1498-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vegunta RK, Raso M, Pollock J, Misra S, Wallace LJ, Torres A, Pearl RH. Biliary dyskinesia: the most common indication for cholecystectomy in children. Surgery. 2005;138:726-731; discussion 731-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Siddiqui S, Newbrough S, Alterman D, Anderson A, Kennedy A. Efficacy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:109-113; discussion 113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Constantinou C, Sucandy I, Ramenofsky M. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia in children: report of 100 cases from a single institution. Am Surg. 2008;74:587-592. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Cay A, Imamoglu M, Kosucu P, Odemis E, Sarihan H, Ozdemir O: Gallbladder dyskinesia: a cause of chronic abdominal pain in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:302-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Campbell BT, Narasimhan NP, Golladay ES, Hirschl RB. Biliary dyskinesia: a potentially unrecognized cause of abdominal pain in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:579-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al-Homaidhi HS, Sukerek H, Klein M, Tolia V. Biliary dyskinesia in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:357-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Carney DE, Kokoska ER, Grosfeld JL, Engum SA, Rouse TM, West KM, Ladd A, Rescorla FJ. Predictors of successful outcome after cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:813-816; discussion 813-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lake AM. Chronic abdominal pain in childhood: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:1823-1830. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Karnsakul W, Vaughan R, Kumar T, Gillespie S, Skitarelic K. Evaluation of gastrointestinal pathology and treatment in children with suspected biliary dyskinesia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:1307-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Scott Nelson R, Kolts R, Park R, Heikenen J. A comparison of cholecystectomy and observation in children with biliary dyskinesia. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1894-1898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vassiliou MC, Laycock WS. Biliary dyskinesia. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1253-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sunderland GT, Carter DC. Clinical application of the cholecystokinin provocation test. Br J Surg. 1988;75:444-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ashorn M, Mäki M, Ruuska T, Karikoski-Leo R, Hällström M, Kokki M, Miettinen A, Visakorpi JK. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in recurrent abdominal pain of childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Squires RH, Colletti RB. Indications for pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy: a medical position statement of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;23:107-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tutel’ian VA, Vasil’ev AV, Kochetkov AM, Pogozheva AV, Lysikova SL, Akol’zina SE, Vorob’eva LSh. [Clinical use of flavonoid enriched biologically active food supplements in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis in combination with chronic cholecystitis or bile ducts dyskinesia]. Vopr Pitan. 2003;72:30-33. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Singhal V, Szeto P, Norman H, Walsh N, Cagir B, VanderMeer TJ. Biliary dyskinesia: how effective is cholecystectomy? J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:135-140; discussion 140-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mehra R, Sodhi KS, Saxena A, Thapa BR, Khandelwal N. Sonographic evaluation of gallbladder motility in children with chronic functional constipation. Gut Liver. 2015;9:388-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ziessman HA, Muenz LR, Agarwal AK, ZaZa AA. Normal values for sincalide cholescintigraphy: comparison of two methods. Radiology. 2001;221:404-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Richmond BK. Optimum utilization of cholecystokinin cholescintigraphy (CCK-HIDA) in clinical practice: an evidence based review. W V Med J. 2012;108:8-11. [PubMed] |

| 21. | DiBaise JK, Richmond BK, Ziessman HA, Everson GT, Fanelli RD, Maurer AH, Ouyang A, Shamamian P, Simons RJ, Wall LA. Cholecystokinin-cholescintigraphy in adults: consensus recommendations of an interdisciplinary panel. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Telega G. Biliary dyskinesia in pediatrics. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8:172-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Haricharan RN, Proklova LV, Aprahamian CJ, Morgan TL, Harmon CM, Barnhart DC, Saeed SA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia in children provides durable symptom relief. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:1060-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Morris-Stiff G, Falk G, Kraynak L, Rosenblatt S. The cholecystokin provocation HIDA test: recreation of symptoms is superior to ejection fraction in predicting medium-term outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:345-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gurusamy KS, Junnarkar S, Farouk M, Davidson BR. Cholecystectomy for suspected gallbladder dyskinesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD007086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Krishnamurthy GT, Krishnamurthy S: Extended application of 99mTc-mebrofenin cholescintigraphy with cholecystokinin in the evaluation of abdominal pain of hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal origin. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;31:346-354. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lyons H, Hagglund KH, Smadi Y. Outcomes after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children with biliary dyskinesia. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:175-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jones PM, Rosenman MB, Pfefferkorn MD, Rescorla FJ, Bennett WE. Gallbladder Ejection Fraction Is Unrelated to Gallbladder Pathology in Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mahida JB, Sulkowski JP, Cooper JN, King AP, Deans KJ, King DR, Minneci PC. Prediction of symptom improvement in children with biliary dyskinesia. J Surg Res. 2015;198:393-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Walker SK, Maki AC, Cannon RM, Foley DS, Wilson KM, Galganski LA, Wiesenauer CA, Bond SJ. Etiology and incidence of pediatric gallbladder disease. Surgery. 2013;154:927-931; discussion 931-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Srinath A, Saps M, Bielefeldt K. Biliary dyskinesia in pediatrics. Pediatr Ann. 2014;43:e83-e88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Singhal V, Wang R S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D