Published online Feb 8, 2017. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v6.i1.81

Peer-review started: July 16, 2016

First decision: August 4, 2016

Revised: October 20, 2016

Accepted: November 1, 2016

Article in press: November 2, 2016

Published online: February 8, 2017

Processing time: 203 Days and 8.3 Hours

To increase evidence-based pain prevention strategy use during routine vaccinations in a pediatric primary care clinic using quality improvement methodology.

Specific intervention strategies (i.e., comfort positioning, nonnutritive sucking and sucrose analgesia, distraction) were identified, selected and introduced in three waves, using a Plan-Do-Study-Act framework. System-wide change was measured from baseline to post-intervention by: (1) percent of vaccination visits during which an evidence-based pain prevention strategy was reported as being used; and (2) caregiver satisfaction ratings following the visit. Additionally, self-reported staff and caregiver attitudes and beliefs about pain prevention were measured at baseline and 1-year post-intervention to assess for possible long-term cultural shifts.

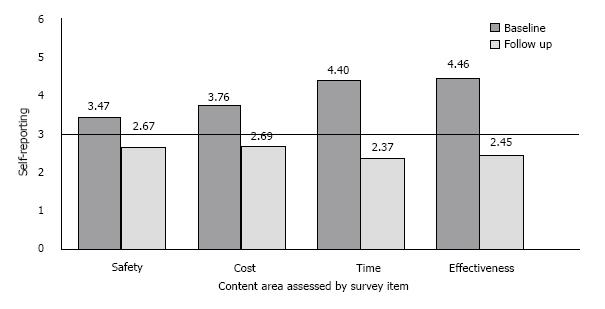

Significant improvements were noted post-intervention. Use of at least one pain prevention strategy was documented at 99% of patient visits and 94% of caregivers were satisfied or very satisfied with the pain prevention care received. Parents/caregivers reported greater satisfaction with the specific pain prevention strategy used [t(143) = 2.50, P≤ 0.05], as well as greater agreement that the pain prevention strategies used helped their children’s pain [t(180) = 2.17, P≤ 0.05] and that they would be willing to use the same strategy again in the future [t(179) = 3.26, P≤ 0.001] as compared to baseline. Staff and caregivers also demonstrated a shift in attitudes from baseline to 1-year post-intervention. Specifically, staff reported greater agreement that the pain felt from vaccinations can result in harmful effects [2.47 vs 3.10; t(70) = -2.11, P≤ 0.05], less agreement that pain from vaccinations is “just part of the process” [3.94 vs 3.23; t(70) = 2.61, P≤ 0.05], and less agreement that parents expect their children to experience pain during vaccinations [4.81 vs 4.38; t(69) = 2.24, P≤ 0.05]. Parents/caregivers reported more favorable attitudes about pain prevention strategies for vaccinations across a variety of areas, including safety, cost, time, and effectiveness, as well as less concern about the pain their children experience with vaccination [4.08 vs 3.26; t(557) = 6.38, P≤ 0.001], less need for additional pain prevention strategies [3.33 vs 2.81; t(476) = 4.51, P≤ 0.001], and greater agreement that their doctors’ office currently offers pain prevention for vaccinations [3.40 vs 3.75; t(433) = -2.39, P≤ 0.05].

Quality improvement methodology can be used to help close the gap in implementing pain prevention strategies during routine vaccination procedures for children.

Core tip: Application of quality improvement methodology can help close the gap in implementing evidence-based pain prevention strategies during routine medical procedures, such as childhood vaccination. A key element to the adoption and maintenance of practice change appears to be building a meaningful partnership with key staff (e.g., nurses who routinely deliver vaccinations) within the target clinic to elicit their expertise and input, as well as facilitate their ownership of the process. Development of project “champions” among key staff can help reduce barriers to implementation, increase uptake of practice change, and shift culture to support long-term maintenance of gains.

- Citation: Schurman JV, Deacy AD, Johnson RJ, Parker J, Williams K, Wallace D, Connelly M, Anson L, Mroczka K. Using quality improvement methods to increase use of pain prevention strategies for childhood vaccination. World J Clin Pediatr 2017; 6(1): 81-88

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v6/i1/81.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v6.i1.81

Pain is a common adverse effect experienced by children undergoing routine medical procedures[1]. Vaccinations are the most frequent painful medical procedure in childhood, with current recommended vaccination schedules including at least 17 injections by a child’s 5th birthday[2]. Failure to treat a child’s pain from even “minor” medical procedures, such as injections, potentially results in greater sensitivity to future pain and other enduring negative effects via the rewiring of a child’s pain transmission pathways and the encoding of pain memories[3-5]. Further, procedural anxiety that develops secondary to pain may contribute to nonadherence to vaccination schedules, needle fear or phobia, and healthcare avoidance into adulthood[6]. A recently published clinical practice guideline provides a comprehensive review of the wide range of evidence-based approaches to the reduction of pain during vaccination[7]. Several policy statements also exist to provide the rationale and evidence-based guidance to translate pain interventions into practice[8-11]. Nevertheless, pain from routine medical procedures often remains undertreated or ignored[8,12,13].

Recognition of this practice gap has led to a surge of attention and effort, nationally and internationally, aimed at bringing routine medical practice in line with current science. Some of these efforts have focused on raising parents’ awareness about children’s pain and increasing parent uptake of evidence-based knowledge in this area (e.g., work by Taddio et al[14] and the “It Doesn’t Have to Hurt” social media campaign; for more information see http://itdoesnthavetohurt.ca/). Other efforts have focused on increasing awareness within the medical community itself[10]. In the current project, we used quality improvement (QI) methodology to address the underuse of evidence-based pain prevention during needlestick procedures within a large primary care practice. Our primary project aim was to increase, in a sustainable way, the use of pain prevention techniques for children vaccinated in our ambulatory primary care clinic to greater than 80% and thus close the observed practice gap. Of note, we were not interested in evaluating the effectiveness of strategy use, as this has been well documented and led to development of the above noted clinical practice guidelines. Instead, we were interested in changes in health care provider behavior to reflect uptake of evidence-based pain prevention strategies. Through improved pain prevention processes, we believed that parent/caregiver perception of his/her child’s vaccination experience also would improve stakeholder engagement and increase willingness on the patient side to use pain prevention strategies again in the future. Satisfaction with pain prevention is recommended as a key outcome variable for pain intervention trials as it is also a significant predictor of return vaccination visits[8,15]. Thus, a secondary aim was to achieve a parent/caregiver pain management satisfaction score of satisfied to very satisfied for greater than 80% of applicable patient visits. Finally, we wanted to assess shifts in staff and parent/caregiver attitudes and beliefs from baseline to 1 year following transition of project control to primary care clinic staff. It was believed that changing the “culture” surrounding pain prevention would be necessary to support sustainability of change in pain prevention procedures for vaccination over the long term.

This project was conducted at a large, urban, academic pediatric medical center. The affiliated Pediatric Care Clinic (PCC) offers a medical home to an ethnically and culturally diverse group of patients who are underserved, uninsured or receiving Medicaid benefits, as well as those who require complex care. The PCC team includes board-certified pediatricians and nurse practitioners, as well as pediatric residents and other medical trainees. The PCC’s 41 physicians and 18 nurse practitioners, with the assistance of approximately 45 nurses, conduct more than 45000 patient visits annually.

We assembled a multidisciplinary team that included pediatric psychologists with expertise in pain, a certified Pain Management nurse, a PCC nursing administrator, a PCC physician, and a QI specialist. A “superuser” group comprised of PCC nurses was formed to couple the evidence base for pain prevention delivery with the culture and function of the vaccination process within the PCC. Nurses invited to participate in the superuser group were strategically selected to vary on years in practice, current use of pain prevention strategies, and anticipated response to change in practice; this ensured that a wide variety of perspectives were represented. The superuser group met a total of three times in a Kaizen-style format over the course of this QI project. In keeping with the spirit of a Kaizen event, these meetings brought together QI team members and the actual “owners” of the process (i.e., nursing staff who actually provide the vaccinations) to identify and make improvements actually within the scope of process participants (vs those needing greater administrative approval and/or financial support). Three interventions targeting the use of pain prevention strategies with routine immunization of children 0-5 years of age were selected from among the wide array of current evidence-based options based on superuser feedback regarding the perceived effectiveness of the technique and relative ease with which that group believed strategies could be incorporated into current practice and clinic flow. Allowing superusers to have a “voice” in the selection process was intended to enhance buy in and likelihood of short-/long-term uptake, while ensuring that interventions remained evidence based. Given intent to disseminate our findings more broadly, the project was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the participating hospital.

Given that this project was designed within a QI framework, outcomes were designed to be easily tracked in an ongoing fashion, or at least in “bursts,” that would require little staff time/effort or disruption to clinic flow. First, PCC staff members were asked to complete surveys constructed by the QI project team regarding their current attitudes, beliefs, and experiences with pain prevention for childhood immunization via the insti

tution’s internal electronic survey software system. Parents/caregivers also were asked to complete paper-and-pencil surveys covering these topics at the time of a PCC visit that were later entered into a database for analysis (see publication by Connelly et al[16] for more details regarding the parent/caregiver survey). All surveys were anonymous. Survey data were collected from staff and parents/caregivers at two time points: (1) at baseline, to inform the development of a key driver diagram; and (2) approximately one year after implementation of the interventions in clinic, to assess shifts in attitudes and beliefs that may reflect and/or support sustainability of change in pain prevention procedures for vaccination over time.

Periodic time-based sampling also was employed to collect information on pain management strategy use at baseline and post-intervention. During each of these data collection bursts, QI project team members identified a convenience sample of approximately 100 vaccination visits occurring for patients within our target age range over a 4-wk period (n = 85 at baseline, n = 101 at post-intervention). Observation and coding of pain behaviors was deemed too burdensome as a long-term data collection/monitoring strategy, particularly as a secondary outcome. Instead, a team member waited outside the exam room door during these visits, and immediately following the vaccinations asked nurses to complete a checklist on what pain prevention strategies were used. The team member then asked each parent a set of standardized questions about his/her child’s vaccination experience and the pain management strategies used. These approaches were believed to be more amenable to automation in the future.

The primary process measure was the proportion of vaccination visits (for children 0-5 years) during which any evidence-based pain prevention strategy was documented as being offered via nursing self-report on a checklist immediately following the vaccination visit.

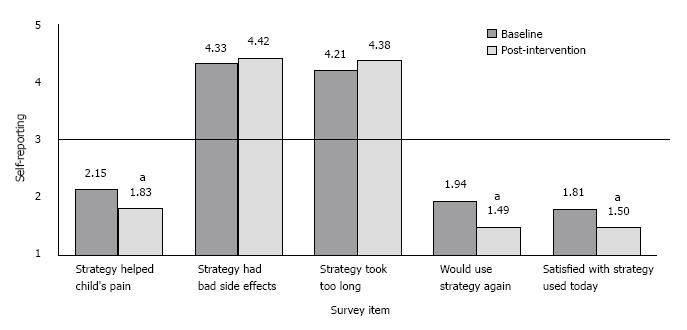

The primary outcome measure was consumer (parent/caregiver) pain prevention satisfaction ratings obtained following the visit. A subset of 3 items was adapted by the QI project team from the Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale[17], which uses a 5-point scale (“very satisfied” to “very dissatisfied” or “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”) to assess satisfaction with and perceived benefit of pain interventions with lower scores indicating more favorable attitudes. Two balancing items also were included. These items, asking about time spent and other potential side effects of using pain prevention strategies during the vaccination visit, were included to detect if improvements in pain control were associated with increases in negative consequences for the child or caregiver that might ameliorate any benefit and/or indicate barriers to be addressed in future Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (see Figure 1 for items).

At baseline, nurses self-reported offering at least one pain prevention strategy 97% of the time (M = 2.16 strategies per target visit). However, the validity of this rate was questionable given informal observation by QI project team members waiting outside the door during target vaccination visits which indicated that nurses were not delivering interventions consistent with evidence-based guidelines. At times, a nurse’s behavior actually ran counter to the intent of the strategy she/he endorsed for that visit (e.g., checking “comfort positioning” on the pain management strategy checklist when restraining a child in the supine position on the exam table). These observed quality issues were not recorded systematically given that this observation was incidental, rather than by design, but were deemed important and subsequently factored into intervention planning. Taken together with survey data collected from staff (see Table 1) and parents/caregivers[16], key drivers deemed important to consider in achieving our project aims included nursing factors (e.g., knowledge, preferences, attitudes), patient factors (e.g., emotional, behavioral, situational), parent factors (e.g., competing demands, cultural beliefs, knowledge), and broader system factors (e.g., time demands, resource availability, nurse/provider communication).

| Percent endorsement by group | |||

| Level of cultural familiarity | Pain prevention strategy | APNs/Nurses | Physicians |

| Most well known | Distraction | ||

| Topical anesthetic creams | |||

| Nonnutritive sucking | |||

| Most commonly trained | Swaddling | ||

| Topical anesthetic creams | |||

| Distraction | |||

| Nonnutritive sucking | |||

| Most typically used in practice | Distraction | ||

| Pre-medication | |||

| Nonnutritive sucking | |||

| Specific belief | |||

| It is important for me, personally, to prevent pain during vaccinations | 64% | 56% | |

| There are effective ways to prevent vaccination pain | 57% | 61% | |

| Pain from vaccinations results in harmful and lasting effects | 14% | 11% | |

| Pain during vaccinations is “just part of the process” | 43% | 17% | |

| Learning to cope with pain (from vaccinations) benefits children | 50% | 17% | |

| Most Salient Reported Barriers to Pain Prevention Use | |||

| Lack of accessibility of pain prevention materials or tools in the clinic | |||

| Not having enough time | |||

| Lack of education among staff | |||

Improvement activities occurred in three phases, as outlined below, using a PDSA model. As noted previously, evidence-based interventions targeting the use of pain prevention strategies with routine vaccination of children 0-5 years of age were selected and prioritized based on superuser feedback regarding the perceived effectiveness and relative ease with which that group believed strategies could be incorporated into current clinic practice (i.e., high impact/low difficulty). All interventions were developed consistent with clinical practice guidelines, including sensitivity to developmental considerations in their use.

Intervention 1: The first intervention focused on the correct use of comfort positioning for vaccinations. The QI project team made an educational video featuring members of our superuser group to increase personal identification with the project and enhance willingness to change behavior related to comfort positioning. Every staff nurse was required to watch this video and then use realistic infant and toddler dolls to demonstrate competent use of comfort positioning with children of varying ages to a QI team member. QI project team members answered questions and provided corrective feedback, as needed, during this simulation experience to ensure that skills were understood and applied correctly. As nurses passed this demonstration task, they received a pin to display on their hospital badge or nursing uniform which identified them as a “Comfort Champion” to others.

Intervention 2: The second intervention focused on the correct use of sucrose analgesia and non-nutritive sucking for vaccinations. A PowerPoint slide show was created to review the rationale and logistics for use of sugar-water mixtures (e.g., Sweet Ease) for the younger end of the age spectrum (≤ 2 years of age). Breastfeeding, as a related intervention, was folded into this presentation. Every staff nurse was required to watch this video and provide attestation to that effect. The QI project team ensured that an appropriate sugar-water mixture was stocked in each medication room and developed/implemented a process to maintain availability over the long-term.

Intervention 3: The third intervention focused on the correct use of distraction for vaccinations. The QI project team made a second educational video showing appropriate distraction techniques modeled by PCC nursing staff, including - but not limited to - members of the superuser group. Each staff nurse was required to watch this video and provide attestation to that effect. The QI project team ensured that a variety of age-appropriate distraction items (including toys, games, and iPads) were available in the clinic, with separate bins for “clean” and “dirty” items. A process also was devised/implemented for ensuring daily cleaning of the items used.

As a final step, the educational modules described above were added to the training requirements for new nursing hires and for biannual nursing education updates with the hope that any culture shift initiated by this project would be continued and strengthened over time through these efforts. A “Process Owner,” a nurse manager in the PCC, was identified to oversee and monitor the system to ensure early detection of instability or deterioration of the changes once control and responsibility for continued success of the project was transferred to the PCC staff.

Unfortunately, the issues with validity of self-report at baseline precluded us from analyzing for pre- to post-change on the rate of evidence-based pain prevention strategies being offered in tandem with vaccination visits. Although this was unfortunate, it was fortuitous that observation uncovered quality issues that might have gone undiscovered and unaddressed within a different design. During the post-intervention period, consistent with our primary aim, nurses self-reported a rate of offering at least one pain prevention strategy 99% of the time. Perhaps most importantly, however, observation by QI project team members waiting outside the door during target vaccination visits yielded no concerns with regard to the validity of these reports and/or to the quality of implementation for strategies used during post-intervention data collection.

With regard to the rate of specific strategy use, nurses self-reported using comfort positioning and distraction approximately half of the time (57% and 54%, respectively) at post-intervention. Nurses self-reported using non-nutritive sucking and sucrose analgesia approximately a quarter of the time (25%) and breastfeeding very rarely (1%). Although not targeted directly by our intervention efforts, nurses self-reported giving the most painful vaccination last nearly three-quarters of the time (73%) at post-intervention, and were observed to encourage parents to dress their children prior to the vaccination(s) to allow parents to more quickly comfort their child and leave the area following the procedure.

Overall parent-/caregiver-reported satisfaction with the vaccination visit as a whole remained high and stable from baseline to post-intervention (94% endorsing a 1 or 2 on a 5-point scale with lower values indicating greater satisfaction). Compared to baseline, however, parents/caregivers reported greater satisfaction with the specific pain prevention strategy used [t(143) = 2.50, P≤ 0.05], as well as greater agreement that the pain prevention strategies used helped their children’s pain [t(180) = 2.17, P≤ 0.05] and that they would be willing to use the same strategy again in the future [t(179) = 3.26, P≤ 0.001; see Figure 1 for details]. Of note, no differences were observed from baseline to post-intervention on items measuring balancing variables (e.g., whether the strategies used took too long or had other bad side effects) that might serve as barriers to uptake (see Figure 2 for baseline values; post-intervention values not depicted).

Approximately 1 year following transition of control and responsibility to PCC staff under the leadership of the Process Owner, staff demonstrated some important shifts in their own attitudes and their perceptions of parents/caregiver attitudes within the context of pain prevention. Specifically, staff reported greater agreement that the pain felt from vaccinations can result in harmful effects [2.47 vs 3.10; t(70) = -2.11, P≤ 0.05], less agreement that pain from vaccinations is “just part of the process” [3.94 vs 3.23; t(70) = 2.61, P≤ 0.05], and less agreement that parents expect their children to experience pain during vaccinations [4.81 vs 4.38; t(69) = 2.24, P≤ 0.05]. Time remained the most commonly reported barrier to use of evidence-based pain prevention strategies at both time periods.

Parents/caregivers also reported more favorable attitudes about pain prevention strategies for vaccinations across a variety of areas, including safety, cost, time, and effectiveness (see Figure 2). In addition, they reported less concern about the pain their children experience with vaccination [4.08 vs 3.26; t(557) = 6.38, P≤ 0.001], less need for additional pain prevention strategies [3.33 vs 2.81; t(476) = 4.51, P≤ 0.001], and greater agreement that their doctors’ office currently offers pain prevention for vaccinations [3.40 vs 3.75; t(433) = -2.39, P≤ 0.05]. Finally, parents/caregivers reported greater agreement that they lack sufficient knowledge about the array of pain prevention strategies that can be used for childhood vaccinations [2.95 vs 3.76; t(399) = -4.54, P≤ 0.001].

Although problems with validity of nursing self-report at baseline challenged our ability to analyze practice change for the number of pain prevention strategies used, we can confidently assert that we met our goal of one (or more) evidence-based pain prevention option being offered during at least 80% of applicable patient visits following the intervention period. In fact, nurses self-reported a rate of 99% of patient visits meeting this criterion. Further, informal observation of clinic visits at post-intervention found none of the discordance between self-report and actual behavior that was noted during the baseline period, lending greater confidence as to the validity of this post-intervention report. Parent data also suggest a qualitative shift occurred over the intervention period in the appropriate use of pain prevention strategies. Specifically, parents/caregivers reported greater agreement that the pain prevention strategies used helped their child’s pain, satisfaction with the strategy used, and willingness to use the strategy again following the intervention phase. This is notable in that parents were generally positive in their satisfaction ratings initially, and yet we were able to demonstrate a positive shift regardless of this potential ceiling effect.

As previously noted, a substantial shift in staff definition of specific pain prevention strategies was required as part of the intervention phase to ensure both that evidence-based techniques were being used and that self-report of health care provider behavior was valid. Currently, pain management is not generally included in nursing curriculums. Findings from this project suggest that, despite the evidence stressing the importance of incorporating evidence-based strategies to manage the pain a patient experiences in the clinical setting, many nurses do not possess the skills and knowledge to incorporate these practices effectively in their daily patient care. Those nurses who do utilize pain management techniques in their patient care delivery models have done so as a result of actual training they have received while on the job and from peers, which may or may not be consistent with evidence-based guidelines. Because of the role nursing plays in many procedures, including - but not limited to - vaccinations, it would have a much greater impact on reducing the pain associated with procedures that patients experience if nurses were educated not just on the importance of pain prevention techniques, but also on the pragmatics of how to utilize and apply these skills in an evidence-based manner to the care that nurses routinely provide, beginning during school to help build a culture supportive of pain mitigation efforts as a part of standard clinical practice.

Fortunately, results from our project suggest that both individual-level and cultural change are possible even in existing systems, under the right conditions. Many clinical/translational projects fail because they try to impose an “ideal” solution on an existing, complex system. In this case, perfect can be the enemy of good. We believe a key component of our success was the application of QI principles to build a partnership with the nurses and providers in the clinic, eliciting their expertise and input, and working to facilitate their ownership of the process. We were able to do this despite some significant deficits in training/experience with pain prevention among the PCC staff, and a culture that did not understand or promote evidence-based pain prevention. Through this process, some of our initial naysayers became the staunchest champions of pain prevention for vaccinations and, in turn, took the lead in modifying the nursing curriculum for new hires to include both the education modules described here and also to create a nursing preceptor position to support and encourage new hires to use evidence-based pain prevention routinely in their vaccination care. Encouraging to us was the fact that, at post-intervention, nurses self-reported generalization beyond the specific pain prevention strategies targeted for intervention (e.g., giving the most painful shot last, encouraging parents/caregivers to dress children before the vaccination is given). Taken together with survey data from the 1-year post-intervention follow up, this suggests an overall increased acceptance by nursing staff that some type of pain prevention is important to offer with every vaccination. By engaging the intended system in solving the problem, we were able to meet our final, long-term aim of shifting staff and parent/caregiver attitudes and beliefs in a sustainable way.

Several other areas for continued iterative improvement remain. The fact that several families were offered comfort positioning and declined in the post-intervention period (7% of those offered the technique) suggests that barriers also remain to the successful use of comfort positioning (e.g., acceptability to parents, application to a more active/distressed child; see Connelly et al[16] for further discussion of this topic). Further, the array of evidence-based pain prevention strategies is wide and we opted to start small with implementing the three that had the greatest support as high impact/low difficulty from our superuser group of PCC nurses. However, combining these more idiographic “nurse-driven” interventions with broadly applied “system-driven” interventions, such as the use of topical anesthetic, has the potential to be even more effective if the logistic (e.g., cost, flow) issues can be resolved at the institutional level. Both of these issues, among others, may provide appropriate targets for intervention in future PDSA cycles. Finally, identifying/implementing an automated method of collecting data on the use of evidence-based pain prevention techniques through the electronic medical record (EMR) would be helpful in both measuring intervention impact over new PDSA cycles while minimizing manpower, as well as for alerting the Process Owner when some type of variation (e.g., outlying points, downward trend in use) occur so that system issues can be addressed in real-time. Setting up the system for sustainability in monitoring can be equally important as setting up the intervention for sustainability in the beginning.

Our current solution may not be the most perfect, but it is a step forward that the system was willing to take on and able to maintain, thus improving the immediate care of our patients and serving as a foundation for future improvement efforts. With our experience, we encourage others to similarly apply QI methods to create “champions” within their own system and promote meaningful, lasting change that narrows the gap between what we know and what we do in providing routine vaccination care to our youngest and most vulnerable patients.

The authors thank the staff and families of the Children’s Mercy Kansas City Pediatric Care Clinic for their contribution to, and support of, this quality improvement project.

Despite strong evidence for the protective and mitigating effects of pain prevention for painful procedures, application to pediatric medical care remains limited. Novel methods to increase the use of evidence-based pain prevention strategies during routine medical procedures, such as pediatric vaccination visits in patients aged 0-5 years, must be explored. Quality improvement (QI) methodology may be a useful approach given that it is designed to engage the intended system and produce sustainable practice change whether in industry or health care.

No evaluation has specifically examined the impact of using QI methods on uptake of pain prevention strategies for routine medical procedures (e.g., vaccination) in pediatric primary care. The objective of this study was to increase the use of evidence-based pain prevention strategies during routine pediatric vaccination visits for patients aged 0-5 years in a single primary care clinic (PCC) using QI methodology.

Self-reported use of evidence-based pain prevention strategies increased from baseline to post-treatment, as did parent/caregiver satisfaction with the strategies used with their child during the vaccination procedure. Most importantly, attitude shifts were noted in both staff and parents/caregivers at 1 year post-intervention which provides support to the sustainability of practice change using QI methods.

Identifying and partnering with “champions” within the target clinic was critical to the adoption and maintenance of evidence-based pain prevention strategies. QI methodology can help close the gap in implementing pain prevention strategies during routine medical procedures for children.

Quality improvement (QI) is an approach to the analysis of performance within a system, whether industry or healthcare, and an associated set of methods designed to support efforts to improve performance at the level of the system.

The authors conducted the evidence-based pain prevention strategies during routine pediatric vaccination visits for patients aged 0-5 years in a single primary care clinic using QI methodology and reported that significant improvements were noted post-intervention. The paper is well-written and provides valuable information regarding this field.

| 1. | The assessment and management of acute pain in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;108:793-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 557] [Cited by in RCA: 528] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommended Vaccination Schedules for Persons Aged 0 Through 18 Years - United States 2015. [Accessed 2015 Dec 28]. Available from: https: //www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/vaccination/Pages/Vaccination-Schedule.aspx. |

| 3. | Kennedy RM, Luhmann J, Zempsky WT. Clinical implications of unmanaged needle-insertion pain and distress in children. Pediatrics. 2008;122 Suppl 3:S130-S133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Taddio A, Katz J. The effects of early pain experience in neonates on pain responses in infancy and childhood. Paediatr Drugs. 2005;7:245-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Reynolds ML, Fitzgerald M. Long-term sensory hyperinnervation following neonatal skin wounds. J Comp Neurol. 1995;358:487-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Taddio A, Ipp M, Thivakaran S, Jamal A, Parikh C, Smart S, Sovran J, Stephens D, Katz J. Survey of the prevalence of immunization non-compliance due to needle fears in children and adults. Vaccine. 2012;30:4807-4812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Taddio A, McMurtry CM, Shah V, Riddell RP, Chambers CT, Noel M, MacDonald NE, Rogers J, Bucci LM, Mousmanis P. Reducing pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. 2015;187:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Taddio A, Chambers CT, Halperin SA, Ipp M, Lockett D, Rieder MJ, Shah V. Inadequate pain management during routine childhood immunizations: the nerve of it. Clin Ther. 2009;31 Suppl 2:S152-S167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schechter NL, Zempsky WT, Cohen LL, McGrath PJ, McMurtry CM, Bright NS. Pain reduction during pediatric immunizations: evidence-based review and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1184-e1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Taddio A, Appleton M, Bortolussi R, Chambers C, Dubey V, Halperin S, Hanrahan A, Ipp M, Lockett D, MacDonald N. Reducing the pain of childhood vaccination: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. 2010;182:E843-E855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | World Health Organization. Reducing pain at the time of vaccination: WHO position paper, September 2015-Recommendations. Vaccine. 2016;34:3629-3630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stevens BJ, Abbott LK, Yamada J, Harrison D, Stinson J, Taddio A, Barwick M, Latimer M, Scott SD, Rashotte J. Epidemiology and management of painful procedures in children in Canadian hospitals. CMAJ. 2011;183:E403-E410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | MacLean S, Obispo J, Young KD. The gap between pediatric emergency department procedural pain management treatments available and actual practice. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Taddio A, Smart S, Sheedy M, Yoon EW, Vyas C, Parikh C, Pillai Riddell R, Shah V. Impact of prenatal education on maternal utilization of analgesic interventions at future infant vaccinations: a cluster randomized trial. Pain. 2014;155:1288-1292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Brown MT, Davidson K, Eccleston C, Finley GA, Goldschneider K, Haverkos L. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:771-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Connelly M, Wallace DP, Williams K, Parker J, Schurman JV. Parent Attitudes Toward Pain Management for Childhood Immunizations. Clin J Pain. 2016;32:654-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Evans CJ, Trudeau E, Mertzanis P, Marquis P, Peña BM, Wong J, Mayne T. Development and validation of the Pain Treatment Satisfaction Scale (PTSS): a patient satisfaction questionnaire for use in patients with chronic or acute pain. Pain. 2004;112:254-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Classen CF, Wang T, Watanabe T S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ