Published online Feb 8, 2017. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v6.i1.40

Peer-review started: May 24, 2016

First decision: July 27, 2016

Revised: September 21, 2016

Accepted: November 21, 2016

Article in press: November 22, 2016

Published online: February 8, 2017

Processing time: 258 Days and 19.9 Hours

To compare the outcome between patients with jejunoileal atresia (JIA) associated with cystic meconium peritonitis (CMP) and patients with isolated JIA (JIA without CMP).

A retrospective study was conducted for all neonates with JIA operated in our institute from January 2005 to January 2016. Demographics including the gestation age, sex, birth weight, age at operation, the presence of associated syndrome was recorded. Clinical outcome including the type of operation performed, operative time, the need for reoperation and mortality were studied. The demographics and the outcome between the 2 groups were compared.

During the study period, 53 neonates had JIA underwent operation in our institute. Seventeen neonates (32%) were associated with CMP. There was no statistical difference on the demographics in the two groups. Patients with CMP had earlier operation than patients with isolated JIA (mean 1.4 d vs 3 d, P = 0.038). Primary anastomosis was performed in 16 patients (94%) with CMP and 30 patients (83%) with isolated JIA (P = 0.269). Patients with CMP had longer operation (mean 190 min vs 154 min, P = 0.004). There were no statistical difference the need for reoperation (3 vs 6, P = 0.606) and mortality (2 vs 1, P = 0.269) between the two groups.

Primary intestinal anastomosis can be performed in 94% of patients with JIA associated with CMP. Although patients with CMP had longer operative time, the mortality and reoperation rates were low and were comparable to patients with isolated JIA.

Core tip: Owing to the adhesive and vascular nature of the meconium cyst, difficult operation is expected in patients with jejunoileal atresia associated with cystic meconium peritonitis. However, whether the overall mortality and morbidity is higher when compare to patients with isolated jejunoileal atresia is not known. Our results showed primary intestinal anastomosis could be performed in majority of neonates with cystic meconium peritonitis without an increase in morbidity and mortality.

- Citation: Chan KWE, Lee KH, Wong HYV, Tsui SYB, Wong YS, Pang KYK, Mou JWC, Tam YH. Cystic meconium peritonitis with jejunoileal atresia: Is it associated with unfavorable outcome? World J Clin Pediatr 2017; 6(1): 40-44

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v6/i1/40.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v6.i1.40

Jejunoileal atresia (JIA) is a common cause of neonatal intestinal obstruction that required operation. With the improvement in neonatal intensive care, timely surgical intervention and parental nutrition, the mortality rate dropped from over 90% to 11%[1]. Cystic meconium peritonitis (CMP) is a result of in-utero perforation of intestine[2]. Although the meconium is sterile, it will lead to secondary inflammation to the peritoneal cavity resulting in fibrosis, calcification and cyst formation[3].

Neonates with JIA associated with CMP required early surgical intervention in view of the coexisting intestinal obstruction. However, in the presence of inflammation and fibrosis, surgery may be difficult as a result of the bleeding and adhesion[4]. In this study, we aim to review the characteristics of patients with JIA and in particular with patients with associated CMP. We would like to study if the presence of CMP has any adverse effect on the clinical outcome.

From January 2005 to January 2016, 53 neonates had JIA operated in our institute. Seventeen neonates (32%) were associated with CMP. A retrospective review was performed on the antenatal diagnosis, gestation age, sex, birth weight, age at operation and the presence of associated syndrome in all neonates with JIA. Clinical outcome including the type of operation performed, operative time, the need for reoperation and mortality were studied. Comparison was made on the demographics and outcome between neonates with JIA associated with CMP and neonates with isolated JIA (JIA without CMP).

Statistical analysis was accomplished using the SPSS program for Windows 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, United States). The Mann-Whitney U Test was used to compare the continuous data. Fisher exact test was used to compare the categorical data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Yuk Him Tam from the Prince of Wales Hospital.

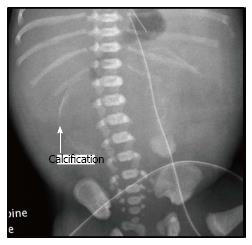

Thirty three male and 20 female neonates with JIA were operated in the study period. The median gestation age was 36 wk (range 26-41 wk). Twenty-seven patients were born prematurely. The median birth weight was 2.8 kg (range 0.82-3.9 kg). Twenty-seven patients had abnormal antenatal ultrasonography (USG). Dilated bowel loop was detected in antenatal USG in 21 patients. Regarding the 17 patients with CMP, 11 patients had abnormalities detected on antenatal USG. USG detected pseudocyst in 5 patients and another 6 patients had dilated bowel shadow without pseudocyst. Calcification was present in the plain radiograph in seven (41%) neonates with CMP (Figure 1). Out of the 35 patients, 7 had associated anomalies (Malrotation of intestine in 3, Meckel’s diverticulum in 2, congenital diaphragmatic hernia in 1, absent toes in 1). No patient had cystic fibrosis. There was no statistical difference on the demographics in the two groups (Table 1).

| JIA with CMP | Isolated JIA | P value1 | |

| (n = 17) | (n = 36) | ||

| Antenatal diagnosis | 11 (65%) | 16 (44%) | 0.139 |

| Sex, M:F | 10:07 | 23:13 | 0.476 |

| Prematurity | 10 (59%) | 17 (47%) | 0.311 |

| Birth weight, kg (mean ± SD) | 2.59 ± 0.92 | 2.71 ± 0.66 | 0.841 |

| Associated anomalies | 1 (6%) | 6 (20%) | 0.269 |

The mean age at operation was 2.5 d (range 0-18 d). Neonates with CMP had earlier operation than neonates with isolated JIA (mean 1.3 d vs 3.0 d, P = 0.039). The type of initial operation including primary intestinal anastomosis (n = 46), fashioning of stoma (n = 6) or drainage procedure (n = 1). Primary intestinal anastomosis was performed in 94% (16/17) of neonates with CMP and 83% (30/36) of neonates with isolated JIA. One patient with CMP had drainage done. She was born prematurely because of maternal sepsis. She was diagnosed to have CMP antenatally. She had sepsis at birth and drainage procedure was performed.

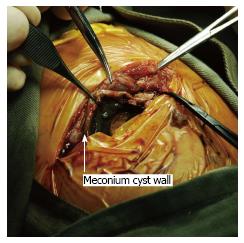

The mean operative time was 166 min. In the presence of fibroadhesion, difficult surgical dissection was experienced in neonates with CMP (Figure 2). They had a significantly longer operative time than neonates with isolated JIA (190 min vs 155 min, P = 0.004) (Table 2).

| JIA with CMP | Isolated JIA | P value1 | |

| (n = 17) | (n = 36) | ||

| Age at operation, d (mean ± SD) | 1.35 ± 1.54 | 3.00 ± 3.78 | 0.0391 |

| Primary anastomosis | 16 (94%) | 30 (83%) | 0.269 |

| Operative time, min (mean ± SD) | 190.38 ± 42.02 | 154.86 ± 45.26 | 0.0041 |

| Reoperation | 2 (12%) | 6 (20%) | 0.493 |

| Mortality | 2 (12%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0.238 |

Regarding the outcome after primary operation, nine neonates (CMP in 3, isolated JIA in 6) required reoperation after primary intestinal anastomosis [intestinal obstruction in 8 and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in 1] (Table 2).

Two patients with CMP died after operation. The first patient underwent primary intestinal anastomosis but was complicated with intestinal obstruction. Stoma was fashioned but the patient died because of sepsis and TPN related liver failure. The second patient was the one with drainage procedure performed. The sepsis was not controlled despite drainage and she passed away at the same day of operation.

One neonate with isolated JIA died because of sepsis and TPN related liver failure. He underwent primary intestinal anastomosis but complicated with intestinal obstruction and required fashioning of stoma. On a median follow-up of 63 mo (range 6 to 123 mo), no patient suffered from short bowl syndrome.

The prevalence of JIA is 0.7 per 10000 births and the prevalence rate of meconium peritonitis is 1 in 30000 livebirth[5,6]. In this review, we studied the characteristics of neonates with CMP, which is a complicated type of meconium peritonitis with the presence of pseudocyst[3]. Our study showed 32% of neonate with JIA has CMP. Unlike in western countries, CMP may be associated with cystic fibrosis[7]. In this study, no patient had cystic fibrosis. It is corresponding to the low incidence of cystic fibrosis in the local population[8].

JIA can be diagnosed antenatally. The presence of maternal polyhydramnios and dilated bowel loops are suggestive features of JIA. The antenatal diagnosed rate (ADR) was reported to be around 30%[9]. In this study, the overall ADR is 51%, which may reflected the more routine use of antenatal ultrasonography in second and third trimester. Besides maternal polyhydramnios and dilated bowel loops, fetus with CMP may have pseudocyst or calcification detected in antenatal ultrasonography[1,8,10]. This additional specific feature reflected the higher ADR rate in neonate with CMP and JIA than in neonate with isolated JIA (65% vs 44%).

In this study, neonates with CMP had earlier operation than neonates with isolated JIA. One of the reasons may be associated with the higher ADR. Moreover, in the presence of the cyst, the abdomens were distended at birth. This alarming feature may lead to early referral to the surgical unit. On the other hand, the clinical features of patients with isolated distal ileal atresia may be more subtle. Abdomen distension may be absent at birth and this may lead to a delay in presentation.

Surgery in neonates with cystic meconium peritonitis is expected to be difficult in view of the underlying fibroadhesion, inflammation and bleeding[4]. We did experience difficulty in surgical dissection and isolation of the intestine from the adherent cyst. Our study confirmed the operative time in patients with CMP was significantly longer than patients with isolated JIA. There were controversies in the literature on the initial approach of patient with CMP[4,11,12]. Some advised for primary drainage procedure in view of the expected difficult operation[12], while other suggested primary intestinal anastomosis should be the treatment of choice[4,11].

Regarding our surgical approach, we opt for primary anastomosis in patients with JIA, no matter it is associated with CMP or not. Despite the difficulty in operation in neonate with CMP, we managed to perform primary intestinal anastomosis in the rest of the cases (93%, 16/17). On the other hand, we performed primary intestinal anastomosis in 83% (30/36) cases only in neonate with isolated JIA.

In primary intestinal anastomosis, the principle of surgery is to excise the dilated aperistaltic proximal intestine and perform the anastomosis[13]. In case there is a marked discrepancy in the diameter between the proximal and distal intestine, stoma will be fashioned. In neonate with CMP, since the perforation of intestine had occurred antenatally and the bowel content was already drained into the peritoneal cavity, the obstructed proximal intestine was partially decompressed. We postulated the decompression led to a less dilated or hypertrophic proximal intestine, which may decreased the discrepancy in diameter between the proximal and distal intestine. In this study, drainage procedure was only performed in one neonate with CMP. She was one of the mortality cases in this study. She was in critical condition after birth and we could only manage to insert a drain soon after delivery and she succumbed on the same day.

The reoperation or mortality rates were comparable between the two groups. Two neonates with CMP had intestinal obstruction and one developed NEC. Six neonates with isolated JIA developed post-operative intestinal obstruction. Our reoperation rate was comparable to other series in literatures[11,13,14]. Despite the preexisting peritoneal adhesions in neonates with CMP, there was no increase in post-operative intestinal obstruction rate. One patient in each group died in the early study period of this series because of total parental nutrition (TPN) related liver failure. With the introduction of fish oil based lipid preparation in TPN in recent years, we did not experience any TPN related liver failure[15] in patients with JIA.

In conclusion, despite longer operative time in patients with JIA associated with CMP, it was not associated with an unfavorable outcome when compare with patients with isolated JIA. With delicate surgical technique, advance in antenatal diagnosis and postnatal care, the morbidity and mortality rate in neonates with JIA remained low.

Cystic meconium peritonitis (CMP) is a result of in-utero bowel perforation. It will lead to secondary inflammation to the peritoneal cavity resulting in fibrosis, calcification and cyst formation. Difficult surgery is expected as a result of the fibroadhesion and inflammation.

Controversies still exist on the initial approach in the management of CMP. Some advocated for primary anastomosis while others suggested for drainage procedure. In addition, whether CMP associated with jejunoileal atresia (JIA) had poorer outcome when compare with patients with isolated JIA is not known.

This study showed primary intestinal anastomosis can be performed in 94% of patients with CMP. When compare with patients with isolated JIA, there is no increase in morbidity and mortality.

Despite longer operation time in patients of CMP as a result of the fibroadhesion, primary intestinal anastomosis is safe and feasible.

Cystic meconium peritonitis (CMP): In utero peroration of intestine leading to secondary inflammation of the peritoneal cavity and resulting in fibrosis, calcification and cyst formation. Jejunoileal atresia: Congenital intestinal atresia involving the jejunum or ileum.

This is a very good paper about an important neonatal surgical condition. Paper is well written, methods are ok, results are well described and conclusion is supported by the data.

| 1. | Stollman TH, de Blaauw I, Wijnen MH, van der Staak FH, Rieu PN, Draaisma JM, Wijnen RM. Decreased mortality but increased morbidity in neonates with jejunoileal atresia; a study of 114 cases over a 34-year period. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:217-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pelizzo G, Codrich D, Zennaro F, Dell’oste C, Maso G, D’Ottavio G, Schleef J. Prenatal detection of the cystic form of meconium peritonitis: no issues for delayed postnatal surgery. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:1061-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lally KP, Mehall JR, Xue H, Thompson J. Meconium stimulates a pro-inflammatory response in peritoneal macrophages: implications for meconium peritonitis. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:214-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Miyake H, Urushihara N, Fukumoto K, Sugiyama A, Fukuzawa H, Watanabe K, Mitsunaga M, Kusafuka J, Hasegawa S. Primary anastomosis for meconium peritonitis: first choice of treatment. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:2327-2331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Best KE, Tennant PW, Addor MC, Bianchi F, Boyd P, Calzolari E, Dias CM, Doray B, Draper E, Garne E. Epidemiology of small intestinal atresia in Europe: a register-based study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F353-F358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Reynolds E, Douglass B, Bleacher J. Meconium peritonitis. J Perinatol. 2000;20:193-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Casaccia G, Trucchi A, Nahom A, Aite L, Lucidi V, Giorlandino C, Bagolan P. The impact of cystic fibrosis on neonatal intestinal obstruction: the need for prenatal/neonatal screening. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:75-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chan KL, Tang MH, Tse HY, Tang RY, Tam PK. Meconium peritonitis: prenatal diagnosis, postnatal management and outcome. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:676-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Basu R, Burge DM. The effect of antenatal diagnosis on the management of small bowel atresia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:177-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bowen A, Mazer J, Zarabi M, Fujioka M. Cystic meconium peritonitis: ultrasonographic features. Pediatr Radiol. 1984;14:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nam SH, Kim SC, Kim DY, Kim AR, Kim KS, Pi SY, Won HS, Kim IK. Experience with meconium peritonitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1822-1825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tanaka K, Hashizume K, Kawarasaki H, Iwanaka T, Tsuchida Y. Elective surgery for cystic meconium peritonitis: report of two cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:960-961. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wang J, Du L, Cai W, Pan W, Yan W. Prolonged feeding difficulties after surgical correction of intestinal atresia: a 13-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1593-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Burjonrappa S, Crete E, Bouchard S. Comparative outcomes in intestinal atresia: a clinical outcome and pathophysiology analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:437-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Lam HS, Tam YH, Poon TC, Cheung HM, Yu X, Chan BP, Lee KH, Lee BS, Ng PC. A double-blind randomised controlled trial of fish oil-based versus soy-based lipid preparations in the treatment of infants with parenteral nutrition-associated cholestasis. Neonatology. 2014;105:290-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Alberti LR S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ