Published online Nov 8, 2016. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v5.i4.358

Peer-review started: June 14, 2016

First decision: July 29, 2016

Revised: August 6, 2016

Accepted: October 1, 2016

Article in press: October 9, 2016

Published online: November 8, 2016

Processing time: 151 Days and 18.1 Hours

To investigate whether serial physical examinations (SPEs) are a safe tool for managing neonates at risk for early-onset sepsis (EOS).

This is a retrospective cohort study of neonates (≥ 34 wks’ gestation) delivered in three high-volume level IIIbirthing centres in Emilia-Romagna (Italy) during a 4-mo period (from September 1 to December 31, 2015). Neonates at risk for EOS were managed according to the SPEs strategy, these were carried out in turn by bedside nursing staff and physicians. A standardized form detailing general wellbeing, skin colour and vital signs was filled in and signed at standard intervals (at age 3, 6, 12, 18, 36 and 48 h) in neonates at risk for EOS. Three independent reviewers reviewed all charts of neonates and abstracted data (gestational age, mode of delivery, group B streptococcus status, risk factors for EOS, duration of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, postpartum evaluations, therapies and outcome). Rates of sepsis workups, empirical antibiotics and outcome of neonates at-risk (or not) for EOS were evaluated.

There were 2092 live births and 1 culture-proven EOS (Haemophilus i) (incidence rates of 0.48/1000 live births). Most newborns with signs of illness (51 out of 101, that is 50.5%), and most of those who received postpartum antibiotics (17 out of 29, that is 58.6%) were not at risk for EOS. Compared to neonates at risk, neonates not at risk for EOS were less likely to have signs of illness (51 out of 1442 vs 40 out of 650, P = 0.009) or have a sepsis workup (25 out of 1442 vs 28 out of 650, P < 0.001). However, they were not less likely to receive empirical antibiotics (17 out of 1442 vs 12 out of 650, P = 0.3). Thirty-two neonates were exposed to intrapartum fever or chorioamnionitis: 62.5% (n = 20) had a sepsis workup and 21.9% (n = 7) were given empirical antibiotics. Among 216 neonates managed through the SPEs strategy, only 5.6% (n = 12) had subsequently a sepsis workup and only 1.9% (n = 4) were given empirical antibiotics. All neonates managed through SPEs had a normal outcome. Among 2092 neonates, only 1.6% (n = 34) received antibiotics; 1.4% (n = 29) were ill and 0.2% (n = 5) were asymptomatic (they were treated because of risk factors for EOS).

The SPEs strategy reduces unnecessary laboratory evaluations and antibiotics, and apparently does not worsen the outcome of neonates at-risk or neonates with mild, equivocal, transient symptoms.

Core tip: The management of asymptomatic neonates at-risk for early-onset sepsis (EOS) remains a challenge. Algorithms based on the threshold values of risk factors result in a large number of uninfected newborns being evaluated and treated. In a 4-mo, multicenter retrospective cohort study, we evaluated a strategy based on serial physical examinations (SPEs) instead of sepsis workup. We studied 2092 neonates. Among 216 neonates initially managed through SPEs, only 12 (5.6%) had subsequently a sepsis workup; only 4 (1.9%) were given empirical antibiotics. All neonates had a normal outcome. SPEs is a simple and reliable tool for managing neonates at risk for EOS.

- Citation: Berardi A, Buffagni AM, Rossi C, Vaccina E, Cattelani C, Gambini L, Baccilieri F, Varioli F, Ferrari F. Serial physical examinations, a simple and reliable tool for managing neonates at risk for early-onset sepsis. World J Clin Pediatr 2016; 5(4): 358-364

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v5/i4/358.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i4.358

Infections are a leading cause of neonatal mortality. Exposure to neonatal infection is a large contributor to cerebral injury and long-term disabilities in survivors, especially in the case of preterm neonates[1-4]. Early-onset sepsis (EOS) is transmitted (during delivery or shortly before) from a mother who is colonized at the genital site[2,5]. EOS may be diagnosed on the basis of nonspecific clinical signs and the isolation of a pathogen from sterile sites. EOS is typically defined as sepsis occurring within the first 3 or 7 d after birth[3]. Seven days is typically used for Group B streptococcus (GBS) sepsis[6,7], that remains a leading cause of EOS[1,2]. Universal screening for GBS in late pregnancy and the administration of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) have led to a striking decline in GBS EOS (from 1.8 cases per 1000 live births in 1990 to 0.25 in 2013 in the United States)[8,9].

The initial symptoms of sepsis are often subtle, but the clinical course may be fulminant, so that neonatologists often initiate antibiotic treatment as soon as there is the slightest clinical suspicion of EOS. There is currently no diagnostic test that can confirm or rule out neonatal sepsis with an acceptable sensitivity and specificity[10,11]. Evidence-based recommendations have been insufficient to date, and neonatal management remains challenging. Guidelines often recommend administering empirical antibiotics to well-appearing neonates at risk of EOS (WAARNs)[12-14]. Algorithms are usually based on the assumption that the presence of maternal risk factors (RFs) implies a higher neonatal risk of EOS. However, most data regarding RFs for EOS have been obtained before the era of IAP. As clinical signs are a sensitive indicator of neonatal sepsis[15]. The 2010 revised Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend observation (instead of laboratory testing) for WAARNs born full term. A sepsis workup is recommended for neonates born after prolonged membrane rupture (≥ 18 h) and inadequate IAP (duration shorter than 4 h prior to delivery). A sepsis workup and empirical antibiotics are recommended for chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates[7]. However, concerns have arisen that unnecessary antibiotics contributes to the development of antimicrobial resistance. A selective use of antibiotics in the highest risk patients is now a universal goal[16]. With the aim of further reducing unnecessary testing and antibiotics, some authors have more recently proposed alternative approaches (based on physical examination) to managing WAARNs[17-20].

In Emilia-Romagna (Italy) a GBS Prevention Working Group was set up in 2003 and active GBS surveillance was started. An efficient antenatal screening strategy for the prevention of EOS has been successfully implemented over the years[21,22].

Since 2009 clinicians have managed WAARNs by relying on serial physical examinations (SPEs) rather than on laboratory tests[23,24]. Since its introduction, this strategy has apparently been safe, so that an increasing number of infants at a higher risk of EOS (i.e., late preterm neonates, or neonates born with chorioamnionitis) have been gradually managed through the SPE strategy.

The purpose of this retrospective study was to confirm that the SPE approach was safe for all WAARNs and was not associated with unnecessary antibiotics. Current data concerning SPEs in WAARNs are limited, especially in neonates exposed to chorioamnionitis at birth, and further data supporting this strategy are needed.

This is a retrospective cohort study of infants delivered during a 4-mo period (from September 1, to December 31, 2015) at three high-volume, level III, regional centres (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico, Modena; Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Policlinico, Parma; and Arcispedale S.M. Nuova, Reggio Emilia) in Emilia-Romagna (an Italian region with about 40000 live births/year). In this region, prevention of GBS infections have led to a decline in the incidence of GBS EOS, which in recent years has decreased to 0.19/1000 live births[23].

Inadequate IAP refers to ampicillin or cefazolin given less than 4 h prior to delivery. Risk factors for EOS: These include GBS bacteriuria identified during the current pregnancy, a previous GBS-infected newborn, preterm birth (< 37 wks’ gestation), rupture of membranes ≥ 18 h, intrapartum fever ≥ 38 °C, that is a surrogate of chorioamnionitis[7]. Well-appearing refers to neonates with risk factors for EOS without any clinical symptom of sepsis at age 0-6 h. At-risk newborn is defined as an infant whose mother is GBS colonized or has risk factors for EOS. Culture-proven EOS: Isolation of a pathogen from a normally sterile body site (blood or cerebrospinal fluid) within 72 h of birth and clinical signs and symptoms consistent with sepsis[2,3]. Suspected EOS is defined as the presence of clinical signs and symptoms consistent with sepsis[1-3] plus an abnormal complete blood count and/or elevated C-reactive-protein levels in the absence of a positive blood culture. Ruled out sepsis: Neonates with signs of illness who rapidly recover without antibiotic treatment.

In accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines[7,13], women with prenatal GBS colonization or risk factors (see below) should be given IAP. Up to 2008, WAARNs underwent a limited laboratory evaluation (complete blood count - CBC - with differential, blood culture and C-reactive protein)[13]. Since 2009 a new strategy (SPE) for managing WAARNs has been implemented[23,24]. A standardized form detailing information on vital signs and general wellbeing was included in the medical records of WAARNs managed through the SPE strategy (see below). Three independent reviewers reviewed all charts of neonates (≥ 34 wk gestation) delivered in the 3 participating centres and abstracted data (gestational age, mode of delivery, GBS status, risk factors for EOS, duration of IAP, postpartum evaluations, therapies and outcome). The results of standardized forms detailing SPEs were also reviewed. To maintain patient confidentiality, the spreadsheets submitted to the principal investigator did not include any data that would have allowed identification of patients or caregivers.

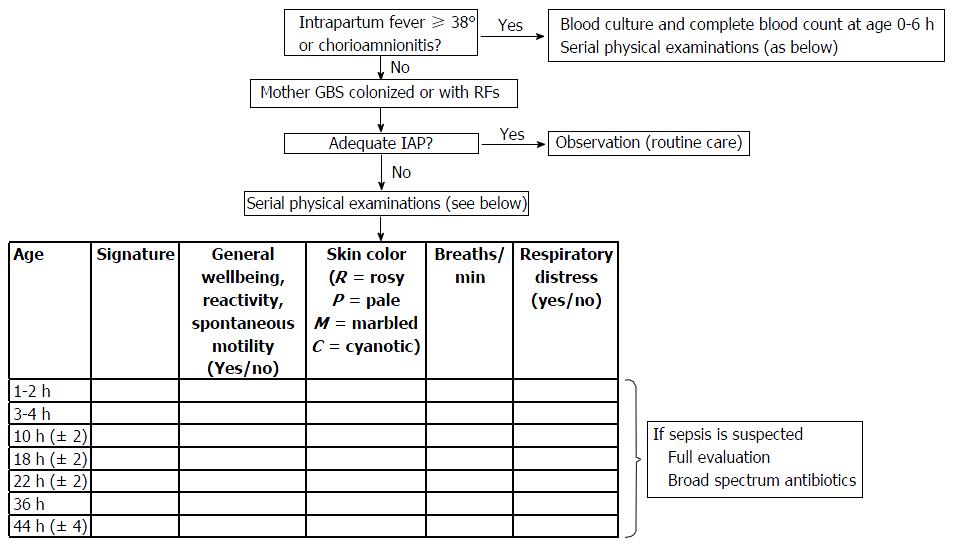

Full-term and late preterm WAARNs who received inadequate or no IAP are managed through SPEs, without any laboratory evaluations. This strategy is carried out in turn by bedside nursing staff, midwives and physicians. It is based on the relief of simple vital signs, these may be easily detected by medical and non-medical staff. Each examiner fills in and signs a standardized form (detailing general wellbeing, skin colour - including perfusion and the presence of respiratory signs) at standard intervals (at age 3-6-12-18-36-48 h) (Figure 1). The standardized form is then included in the records of the newborn. Nursing staff and midwives give notification to clinicians when signs of illness develop. As we experienced in our clinical practice, every evaluation requires a maximum of 1 to 2 min. SPE has proven very sensitive for the early detection of all cases of EOS, not only for GBS sepsis.

Neonates with mild or equivocal symptoms during the first hours of life (i.e., neonates born by caesarean section with mild tachypnea that resolves spontaneously within a few hours) are closely observed, but do not necessarily undergo a sepsis workup or receive empirical antibiotics. Antibiotics are given after the collection of blood samples and (when possible) cerebrospinal fluid cultures. WAARNs are not discharged home before age 48 h.

From 2009 to 2012, SPEs were performed on WAARNs ≥ 35 wks’ gestation. However, intrapartum fever/chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates or neonates with ≥ 2 risk factors underwent sepsis workup and were given empirical antibiotics[24]. Because of its apparent safety, in 2013 this SPE strategy was extended to all WAARNs ≥ 34 wks’ gestation, regardless of RFs.

Analyses were performed using STATA/SE 11.2 for Windows; continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median and range; categorical data were expressed as numbers (percentages). Statistical analyses were performed using the χ2 test and Mann-Whitney test for independent samples, when appropriate. A P value < 0.05 was used as a threshold for statistical significance.

During the study period there were 2092 newborns with ≥ 34 wks’ gestation; the median gestational age was 39 wk (25th-75th IQ range 38-40) and median birth weight was 3920 g (25th-75th IQ range 2980-3590).

Table 1 shows the demographics of neonates according to maternal colonization, risk factors, and IAP administration. Approximately 27% of neonates had at least 1 risk factor for EOS, and 20% were born to mothers with a positive GBS screening. The vast majority of them received IAP (which in most cases was given more than 4 h prior to delivery).

| Mothers | n = 2092 |

| Antenatal screening, n (%) | 1923 (91.9) |

| GBS culture-positive, n (%) | 392 (20.4) |

| Mothers with risk factor, n (%) | 578 (27.6) |

| GBS bacteriuria during pregnancy, n (%) | 116 (5.5) |

| Previous infant with GBS disease, n (%) | 1 (0.05) |

| Preterm delivery (34 to 36 wks’ gestation), n (%) | 123 (5.9) |

| Intrapartum fever ≥ 38 °C, n (%) | 32 (1.5) |

| Membrane rupture ≥ 18 h, n (%) | 254 (12.1) |

| Vaginal delivery, n (%) | 1507 (72) |

| IAP administration, n (%) | 771 (36.8) |

| IAP given more than 4 h prior to delivery, n (%) | 470 (61.0) |

| IAP given to culture-positive women, n (%) | 341 (87.0) |

| Gestational age, weeks, median, (IQ) | 39.0 (38-40) |

| Birth weight, g, median (IQ) | 3290 (2980-3590) |

Thirty-two neonates were intrapartum fever/chorioamnionitis-exposed. Seven of 32 had signs of illness (of which 4 at age 0-6 h and 3 at age 7-24 h). Twenty out of 32 (62.5%) had a sepsis workup, but only 7 (21.9%) were given empirical antibiotics. All had a normal outcome and none of them had culture-proven sepsis.

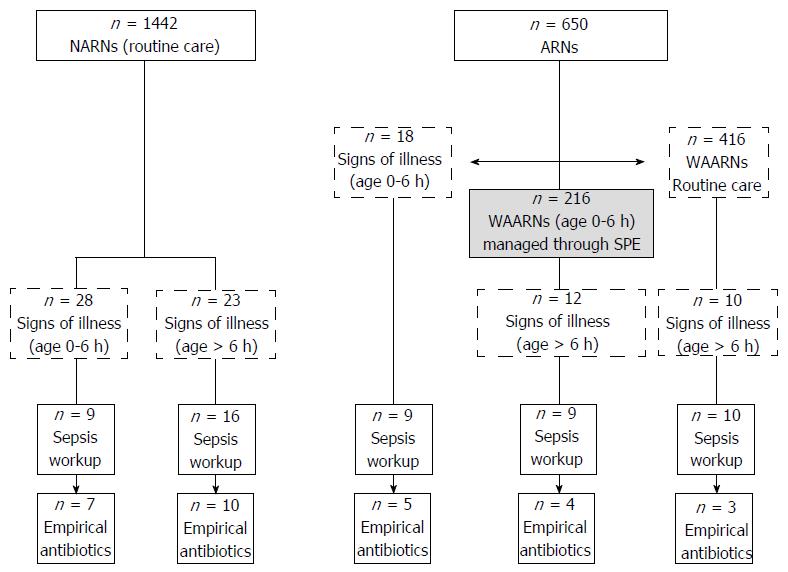

Figure 2 presents data for neonates at risk (or not) for EOS and details of neonates with signs of illness, sepsis workup and empirical antibiotics. Most newborns with signs of illness, and most of those who received postpartum antibiotics were not at risk. However, compared to neonates at risk, neonates not at risk for EOS were less likely to have signs of illness (51 out of 1442 vs 40 out of 650, P = 0.009) or have a sepsis workup (25 out of 1442 vs 28 out of 650, P < 0.001), but not less likely to receive empirical antibiotics (17 out of 1442 vs 12 out of 650, P = 0.3). Among 18 at-risk neonates with signs of illness at age 0-6 h, 9 had mild, equivocal and transient symptoms and were kept under observation without further evaluation; the remaining 9 neonates underwent a sepsis workup.

Among the 2092 newborns, 216 (10.3%) initially WAARNs were managed through SPEs; only 12 of 216 (5.6%) had a sepsis workup (because of respiratory signs in most cases) and 4 of 216 (1.9%) were given antibiotics. Sepsis was ruled out in the remaining 8 neonates who had a sepsis workup (as neonates recovered promptly without any antibiotic treatment).

Postpartum antibiotics were given to 34 (1.6%) of the 2092 neonates, of whom 5 (0.2%) were asymptomatic (they were given antibiotics because of risk factors for EOS) and 29 (1.4%) had signs of illness (respiratory signs in 23 out of 29 neonates). Nine required oxygen support (chest X-rays were consistent with pneumonia in 4 cases), none received nasal CPAP or mechanical ventilation. Twelve of the 29 neonates (41.4%) presented with symptoms at age 0-6 h. One of them had culture proven sepsis (caused by Haemophilus i.). The baby was born at 35 wks’ gestation to a GBS-negative mother and was given no IAP. Seventeen of the 29 (58.6%) presented with symptoms at age 7 to 63 h. Four of these 17 neonates had been managed initially through the SPE strategy (Figure 2).

All 34 neonates who were given postpartum antibiotics had a sepsis workup before treatment (all had blood culture obtained; 11 underwent also lumbar puncture), and all had a normal outcome, without brain lesions at ultrasound scanning (when performed).

Since IAP has become a standard of care, the management of WAARNs has remained a challenge for clinicians. Laboratory tests currently available have poor specificity, low positive predictive value and lack sufficient accuracy for guiding the decision as to whether neonates should be treated with antibiotics[10]. Most guidelines for neonatal management rely on studies carried out prior to the era of IAP. However, IAP leads to a substantial reduction of the risk of EOS. Recent studies show that algorithms based on the threshold values of risk factors may result in a large number of uninfected newborns being evaluated and treated; or they may fail to identify many newborns who require early treatment[11,18,19]. Therefore, new data are necessary in order to develop alternative approaches.

More recently, methods to stratify the risk of EOS by combining different maternal RF groups and clinical examination of newborns have been devised[25]. It is however unclear what impact these methods have on preventing the occurrence of sepsis or what impact they have on the number of asymptomatic newborns unnecessarily treated with antibiotics. Such methods still recommend empirical antibiotics for some WAARNs. A recent study aimed at evaluating the impact of this strategy among 2094 newborns found that 5.3% of full-term neonates were given empirical antibiotics, but more than 40% of them were asymptomatic[26].

A second controversial issue concerns the management of chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates. Early studies reported that most failures of IAP (up to 90% of cases) occur in such neonates[27]. However, recent data show that less than 50% of failures of IAP are tied to chorioamnionitis[28] and the risk of EOS is strongly dependent on gestational age[11]. Because most asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed neonates are born full term, the number of neonates to be evaluated and treated empirically (number needed to treat) in order to prevent one infection may be high (60-1400 newborns) and antibiotic treatment might not be justified for full-term neonates[29].

In the current study, the low incidence of culture-proven EOS (0.48/1000) was the result of high rates of maternal prenatal screening and IAP. No cases of GBS-EOS occurred in the study period. This finding is consistent with regional data, which clearly show a continuous decline in GBS-EOS over the years, thanks to the implementation of the prevention strategy[23].

Most newborns had symptoms at birth or in the first few hours of life, and most had apparently no risk factors for EOS. Under our approach, neonates with mild or equivocal, initial symptoms or asymptomatic neonates with risk factors for EOS underwent SPEs without sepsis workup. Furthermore, only approximately 2/3 of neonates exposed to intrapartum fever or chorioamnionitis had a sepsis workup and only 21% (neonates with signs of illness) were given antibiotics. We could not calculate the number needed to treat, as we had no cases of EOS among initially asymptomatic neonates managed through SPEs.

This less invasive approach has resulted in very few infants (1.6%) treated with antibiotics. Nevertheless, no cases of EOS were missed, as all neonates had a sepsis workup (including blood culture) prior to administering antibiotics. Furthermore, none of the newborns had complications or a worse outcome because of this strategy. By providing strong assurance that frequent examinations actually are performed, this strategy seems safe, reliable and easy to perform.

This study has major limitations, firstly the small sample size of neonates in study. EOS has become rarer than in the past, therefore larger population is required in order to better define neonatal risks. This is especially true for intrapartum fever/chorioamnionitis-exposed newborns, who represent approximately 1% in our population. However, starting from 2003, we recommended an SPE-based approach for the entire region, but the GBS-EOS surveillance network has to date reported no cases of delayed diagnosis. Moreover, our study addresses neonates aged 0-72 h, and we could not exclude that some newborns have fallen ill after the first days of life. However, our approach does not seem to increase the risk of subsequent complications[24].

In conclusion, our study suggests that the SPE strategy may reduce unnecessary laboratory evaluations and antibiotics, apparently without worsening the outcome. However, larger studies are needed to validate this strategy.

There are insufficient evidence-based recommendations for managing well-appearing neonates at-risk for early-onset sepsis (EOS). Algorithms based on the threshold values of risk factors may result in a large number of uninfected newborns being evaluated and treated; or they may fail to identify many newborns who require early treatment.

New data are necessary in order to develop alternative approaches.

In this 4-mo, multicenter retrospective cohort study, we studied 2092 neonates, of which > 30% were at-risk for EOS; 216 neonates were initially managed through a strategy based on serial physical examinations (SPEs) instead of sepsis workup. Only 12 (5.6%) had subsequently a sepsis workup and only 4 (1.9%) were given empirical antibiotics. All neonates managed through SPEs had a normal outcome. Among 2092 neonates, only 1.6% (n = 34) were given antibiotics (all but 5 had clinical symptoms consistent with sepsis). Most of them were not at risk for EOS.

A strategy based on SPEs reduces unnecessary sepsis workup and antibiotics, and does not worsen the outcome.

SPEs are carried out in turn by bedside nursing staff, midwives and physicians. at standard intervals (at age 3-6-12-18-36-48 h). A standardized form (detailing general wellbeing, skin colour - including perfusion and the presence of respiratory signs) filled in and signed by the staff is then included in the records of the newborn.

The reviewed article raises important topic of newborn babies potentially at risk of early infection (EOS) because of maternal Group B streptococcus colonization or the existence of other risk factors or the presence of non-specific signs of infection. At the same time, as the authors point out, the real risk for a newborn - in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis - is not so common in the group of term and late preterm infants. Driven by concern about the excessive use of antibiotics, as well as exposing the infant to pain when performing laboratory tests, the authors propose a clinical observation in the form of repeated physical evaluation every few hours in the first days of life. It is well-written.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aceti A, Lloreda-Garcia JM, Maruniak-Chudek I, Oliveira L S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Palazzi D, Klein J, Baker C. Bacterial sepsis and meningitis. In Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant. 6th ed. In: Remington J, Klein J, Wilson C, Baker C. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2006: 247-295. . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Simonsen KA, Anderson-Berry AL, Delair SF, Davies HD. Early-onset neonatal sepsis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:21-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 619] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Ganatra HA, Stoll BJ, Zaidi AK. International perspective on early-onset neonatal sepsis. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:501-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Strunk T, Inder T, Wang X, Burgner D, Mallard C, Levy O. Infection-induced inflammation and cerebral injury in preterm infants. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:751-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Di Renzo GC, Melin P, Berardi A, Blennow M, Carbonell-Estrany X, Donzelli GP, Hakansson S, Hod M, Hughes R, Kurtzer M. Intrapartum GBS screening and antibiotic prophylaxis: a European consensus conference. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:766-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Berardi A, Cattelani C, Creti R, Berner R, Pietrangiolillo Z, Margarit I, Maione D, Ferrari F. Group B streptococcal infections in the newborn infant and the potential value of maternal vaccination. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13:1387-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease--revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-36. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Rodriguez-Granger J, Alvargonzalez JC, Berardi A, Berner R, Kunze M, Hufnagel M, Melin P, Decheva A, Orefici G, Poyart C. Prevention of group B streptococcal neonatal disease revisited. The DEVANI European project. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:2097-2104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Report, Emerging Infections Program Network, Group B Streptococcus. [accessed 2016 Mar 17]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reportsfindings/survreports/gbs13.pdf. |

| 10. | Benitz WE. Adjunct laboratory tests in the diagnosis of early-onset neonatal sepsis. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:421-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Benitz WE, Wynn JL, Polin RA. Reappraisal of guidelines for management of neonates with suspected early-onset sepsis. J Pediatr. 2015;166:1070-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Antibiotics for Early-Onset Neonatal Infection: Antibiotics for the Prevention and Treatment of Early-Onset Neonatal Infection. London: RCOG Press, 2012. . [PubMed] |

| 13. | Schrag S, Gorwitz R, Fultz-Butts K, Schuchat A. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease. Revised guidelines from CDC. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51:1-22. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Alós Cortés JI, Andreu Domingo A, Arribas Mir L, Cabero Roura L, de Cueto López M, López Sastre J, Melchor Marcos JC, Puertas Prieto A, de la Rosa Fraile M, Salcedo Abizanda S. [Prevention of Neonatal Group B Sreptococcal Infection. Spanish Recommendations. Update 2012. SEIMC/SEGO/SEN/SEQ/SEMFYC Consensus Document]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2013;31:159-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Escobar GJ, Li DK, Armstrong MA, Gardner MN, Folck BF, Verdi JE, Xiong B, Bergen R. Neonatal sepsis workups in infants >/=2000 grams at birth: A population-based study. Pediatrics. 2000;106:256-263. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Cantey JB, Patel SJ. Antimicrobial stewardship in the NICU. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2014;28:247-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ottolini MC, Lundgren K, Mirkinson LJ, Cason S, Ottolini MG. Utility of complete blood count and blood culture screening to diagnose neonatal sepsis in the asymptomatic at risk newborn. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:430-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hashavya S, Benenson S, Ergaz-Shaltiel Z, Bar-Oz B, Averbuch D, Eventov-Friedman S. The use of blood counts and blood cultures to screen neonates born to partially treated group B Streptococcus-carrier mothers for early-onset sepsis: is it justified? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:840-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Flidel-Rimon O, Galstyan S, Juster-Reicher A, Rozin I, Shinwell ES. Limitations of the risk factor based approach in early neonatal sepsis evaluations. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:e540-e544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cantoni L, Ronfani L, Da Riol R, Demarini S. Physical examination instead of laboratory tests for most infants born to mothers colonized with group B Streptococcus: support for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2010 recommendations. J Pediatr. 2013;163:568-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Berardi A, Lugli L, Baronciani D, Creti R, Rossi K, Ciccia M, Gambini L, Mariani S, Papa I, Serra L. Group B streptococcal infections in a northern region of Italy. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e487-e493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Berardi A, Lugli L, Baronciani D, Rossi C, Ciccia M, Creti R, Gambini L, Mariani S, Papa I, Tridapalli E. Group B Streptococcus early-onset disease in Emilia-romagna: review after introduction of a screening-based approach. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Berardi A, Lugli L, Rossi C, Guidotti I, Lanari M, Creti R, Perrone E, Biasini A, Sandri F, Volta A. Impact of perinatal practices for early-onset group B Streptococcal disease prevention. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:e265-e271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Berardi A, Fornaciari S, Rossi C, Patianna V, Bacchi Reggiani ML, Ferrari F, Neri I, Ferrari F. Safety of physical examination alone for managing well-appearing neonates ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation at risk for early-onset sepsis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1123-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Escobar GJ, Puopolo KM, Wi S, Turk BJ, Kuzniewicz MW, Walsh EM, Newman TB, Zupancic J, Lieberman E, Draper D. Stratification of risk of early-onset sepsis in newborns ≥ 34 weeks’ gestation. Pediatrics. 2014;133:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kerste M, Corver J, Sonnevelt MC, van Brakel M, van der Linden PD, M Braams-Lisman BA, Plötz FB. Application of sepsis calculator in newborns with suspected infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:3860-3865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Benitz WE, Gould JB, Druzin ML. Risk factors for early-onset group B streptococcal sepsis: estimation of odds ratios by critical literature review. Pediatrics. 1999;103:e77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Velaphi S, Siegel JD, Wendel GD, Cushion N, Eid WM, Sánchez PJ. Early-onset group B streptococcal infection after a combined maternal and neonatal group B streptococcal chemoprophylaxis strategy. Pediatrics. 2003;111:541-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wortham JM, Hansen NI, Schrag SJ, Hale E, Van Meurs K, Sánchez PJ, Cantey JB, Faix R, Poindexter B, Goldberg R. Chorioamnionitis and Culture-Confirmed, Early-Onset Neonatal Infections. Pediatrics. 2016;137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |