Published online Aug 8, 2016. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v5.i3.301

Peer-review started: January 26, 2016

First decision: March 24, 2016

Revised: May 3, 2016

Accepted: July 11, 2016

Article in press: July 13, 2016

Published online: August 8, 2016

Processing time: 196 Days and 9.9 Hours

AIM: To determine the prevalence of recent immunisation amongst children under 7 years of age presenting for febrile convulsions.

METHODS: This is a retrospective study of all children under the age of seven presenting with febrile convulsions to a tertiary referral hospital in Sydney. A total of 78 cases occurred in the period January 2011 to July 2012 and were included in the study. Data was extracted from medical records to provide a retrospective review of the convulsions.

RESULTS: Of the 78 total cases, there were five medical records which contained information on whether or not immunisation had been administered in the preceding 48 h to presentation to the emergency department. Of these five patients only one patient (1.28% of the study population) was confirmed to have received a vaccination with Infanrix, Prevnar and Rotavirus. The majority of cases reported a current infection as a likely precipitant to the febrile convulsion.

CONCLUSION: This study found a very low prevalence of recent immunisation amongst children with febrile convulsions presenting to an emergency department at a tertiary referral hospital in Sydney. This finding, however, may have been distorted by underreporting of vaccination history.

Core tip: This study found a very low prevalence of recent immunisation amongst children with febrile convulsions. This finding, however, may have been distorted by underreporting of vaccination history. The use of large linked datasets may determine a more accurate estimate of the rate of febrile convulsions due to immunisation.

- Citation: Motala L, Eslick GD. Prevalence of recent immunisation in children with febrile convulsions. World J Clin Pediatr 2016; 5(3): 301-305

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v5/i3/301.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i3.301

There has been much controversy in recent years about the risks vs the benefits of childhood vaccination[1,2]. Vaccines may have adverse effects which range from simple fever[3] to more severe febrile convulsions[3-10]. Febrile convulsions can be defined as any seizure that is associated with fever, and not due to intracranial infection or other known cause such as epilepsy or head trauma[4,11].

Of particular interest, has been the association between the influenza, diphtheria-tetanus toxoids-pertussis (DTP) and measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccines and febrile convulsions. Western Australia observed a spike in emergency department presentations for high fever and febrile convulsions in young children after vaccination with the 2010 trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV)[5]. This resulted in a country-wide suspension of the use of TIV in children aged 5 years and under[5]. Further investigation into the matter then indicated that an association between TIV and febrile convulsions in children was prevalent across the majority of Australia[5]. Following these findings, a similar study performed in the United States revealed disproportionately higher rates of febrile convulsion associated with 2010-2011 TIV administration compared with other vaccines[12]. The majority (84%) of these convulsions occurred in children under 2 years of age, and most (86%) had an onset of convulsion on the same day or the day after the vaccination[12]. The suspension of the use of TIV in children under 5 in Australia was later lifted when it was found that the risk of febrile convulsions following TIV was specific to vaccination with Fluvax® and did not apply to the use of other seasonal influenza vaccines such as Vaxigrip® or Panvax®[3,6].

Although febrile convulsions generally have an excellent prognosis, they are the commonest cause of status epilepticus in childhood[4]. Their occurrence can be extremely distressing for family members of patients, and may have serious long-term consequences that are as yet unknown. A high rate of these seizures following vaccination would have important clinical implications as it may lead to poor vaccine uptake and the risk should be diminished where possible - perhaps, by the administration of alternate safer vaccines[3,6] or by the use of antipyretics and physical methods to reduce fever[3].

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of recent immunisation amongst children under the age of seven presenting with febrile convulsions to a teaching hospital in Western Sydney.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sydney West Area Health Service. The study population included all patients presenting to Nepean Hospital Emergency Department with febrile convulsion based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-AM) codes (R56.0).

Two linked databases were set up in order to de-identify the data. The first database comprised of a unique patient identification number, name and medical records number. The following variables were collected from each medical record: Age (months); gender; weight; method of transport to hospital; primary diagnosis; additional diagnosis; number of febrile convulsions during current presentation; history of fever; antipyretic given prior to febrile convulsion; maximum temperature; length of convulsion; previous history of febrile convulsion; previous history of non-febrile convulsion; precipitant to previous febrile convulsion; history of current infection; history of vaccination/immunisation; number of vaccinations; time between vaccination and febrile convulsion; type of vaccination; history of concurrent illness; family history of febrile convulsions; family history of epilepsy; and length of stay.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics have been reported as median and range for numeric-scaled features and percentages for discrete characteristics. Factors associated with febrile convulsion were identified using unconditional logistic regression. All P values calculated were two-tailed; the alpha level of significance was set at 0.05. All data was analysed using STATA version 12.0 (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

A total of 78 patients with a mean age of 23 mo (1-63 mo; 60% male) presented to Nepean Hospital for febrile convulsions over the 19 mo period (January 2011 - July 30 2012).

The primary diagnosis of febrile convulsion was made in 56.4% of cases, with the majority of the remaining patients being diagnosed with acute upper respiratory tract infections and a smaller number with acute intestinal infections. The mean maximum temperature reported was 39.5 °C (37.3 °C-43 °C). For each presentation, the mean number of febrile convulsive episodes was 1.7 (1-8 episodes), and the average length of convulsion was 3 min (30 s-20 min). Just over half the medical records (56%) had evidence of antipyretics administration prior to the convulsions. A large proportion of cases (89%) were given antipyretics before their convulsions, with the average time between drug administration and convulsion being 5 h and 45 min.

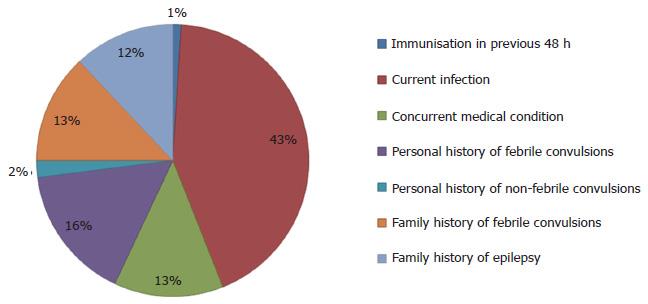

Five medical records contained information on whether or not immunisation had been administered in the 48 h preceding the febrile convulsion, with only one having clear information on immunisation (confirmed receipt of vaccination with Infanrix, Prevnar and Rotavirus) (Figure 1). Almost all patients (96%) reported a current infection as a possible precipitant to the febrile convulsion, and 25% had a concurrent medical condition such as developmental delay. For those aged > 2 years, a previous history of febrile convulsions was a significant risk factor (OR = 5.47; 95%CI: 1.92-15.60) for presentation. They were also more likely to have shorter convulsions (3 min or less) (OR = 1.67; 95%CI: 0.53-5.27). A positive family history of febrile convulsions but not epilepsy was also a potential risk factor in this age group (OR = 1.30; 95%CI: 0.44-3.84). These individuals were also more likely to have received an antipyretic at an appropriate time - that is from 20 min to 4 h prior to the convulsive episode (OR = 2.28; 95%CI: 0.52-9.99). Males were more likely to be given a primary diagnosis of febrile convulsions than females (OR = 1.72; 95%CI: 0.70-4.35).

The mean length of stay was 2 d (1-4 d), with the most common follow-up diagnostic tests including electroencephalograms (15%) and brain magnetic resonance imaging (4%).

This study determined that there was a very low prevalence of recent immunisation amongst children with febrile convulsions presenting to a tertiary referral hospital in Western Sydney. This finding, however, may have been due to underreporting of vaccination history as the vast majority of medical records contained no information on whether or not immunisation was administered in the recent past. Only 6% of medical records contained information on immunisation.

Previous studies have shown that some vaccines such as MMR[10] and DTaP-IPV-Hib[8] were associated with an increased risk of febrile convulsions, but that this risk was small. Conversely, another study reported a significantly elevated risk of febrile seizures following receipt of DTP or MMR vaccine[7]. This study determined that a history of a current infection was the predominant precipitant for fever and thus convulsion, previous studies suggest that viral illness is the most common reason for hospitalisation with febrile convulsion[4].

Individuals older than 2 years of age were more likely to have a previous history of febrile convulsions. In terms of the average age at which febrile convulsions tend to occur, this study concurred with the findings of previous research[13] and established that this was at an age of about 2 years.

Males were more likely to be given a primary diagnosis of febrile convulsion than females. This may have been attributable to the fact that approximately 60% of febrile convulsions are known to occur in male children[13,14], and may well indicate some degree of bias involved in diagnosis. Furthermore, male participants were found to be admitted to hospital more frequently - recent literature suggests that this excess of male admissions[15] is consistent with an increased vulnerability to illness amongst the gender[14].

The higher rate of appropriate antipyretic use that was observed amongst children with a personal history of febrile convulsions was possibly due to those parents being familiar with the occurrence of seizures and thus more cautious when fever arose. This study, much like previous reports, indicated higher rates of febrile convulsions in children with a personal or family history of these seizures[10,16].

One of the strengths of the study was that the aim, hypothesis and objectives were arrived at a priori examination of medical records. Furthermore, all medical records were thoroughly examined manually. The use of medical records as a source of data could also be considered a limitation of the study since some records were incomplete, however, this was not substantial. The sample size did not provide statistical significance for some of our results.

This study found a low prevalence of recent immunisation precipitating febrile convulsions in young children, but this finding may have been distorted by the low rates of accurate reporting of immunisation. A recommendation for future practice would, therefore, be that physicians directly request and record information on immunisation, particularly when dealing with cases of childhood febrile convulsions.

Febrile convulsions are an important reason for children presenting to hospital emergency departments. The causes of these febrile convulsions are varied but immunization/vaccination may be a factor.

The authors’ suggest that immunization associated febrile convulsions are an under-reported presentation to the emergency department. Specific studies to address this issue are required. Moreover, preventive strategies may be implemented to reduce the risk of febrile convulsions after immunization.

Vaccine safety is vitally important to the continued global approach to preventable infectious diseases both in childhood and adulthood. A greater understanding of minor and major adverse events following immunization are required. Recent high level evidence providing no link between vaccines and autism is a good example.

A greater knowledge of the potential adverse effects of immunization is important and education of patients with regards to preventive and recognition of adverse effects early is critical.

The Measles, Mumps, Rubella vaccine protects against measles, mumps, and rubella (German measles). It is a mixture of live attenuated viruses of the three diseases, administered via injection. The (DTaP-IPV-Hib) includes diphtheria (D), tetanus (T) and acellular pertussis (aP) (whooping cough). Inactivated polio vaccine stands for “inactivated polio vaccine”. Hib stands for Haemophilus influenzae type b.

Good study provided record based immunization history is of quality.

| 1. | Shorvon S, Berg A. Pertussis vaccination and epilepsy--an erratic history, new research and the mismatch between science and social policy. Epilepsia. 2008;49:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Berg AT. Seizure risk with vaccination [accessed 2012 Jul 20]. Available from: http//www.aesnet.org/files/dmFile/EPCvaccination.pdf. |

| 3. | Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing. Investigation into febrile convulsions in young children after seasonal influenza vaccination [accessed 2012 Jul 20]. Available from: http//www.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/immunise-factsheet-30jul10. |

| 4. | Al-Ajlouni SF, Kodah IH. Febrile convulsions in children. Saudi Med J. 2000;21:617-621. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gold MS, Effler P, Kelly H, Richmond PC, Buttery JP. Febrile convulsions after 2010 seasonal trivalent influenza vaccine: implications for vaccine safety surveillance in Australia. Med J Aust. 2010;193:492-493. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) and Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) Joint Working Group. Report of an analysis of febrile convulsions following immunisation in children following monovalent pandemic H1N1 vaccine (Panvax/Panvax Junior, CSL) [accessed 2012 Jul 20]. Available from: http//www.tga.gov.au/safety/alerts-medicine-seasonal-flu-100928.htm. |

| 7. | Barlow WE, Davis RL, Glasser JW, Rhodes PH, Thompson RS, Mullooly JP, Black SB, Shinefield HR, Ward JI, Marcy SM. The risk of seizures after receipt of whole-cell pertussis or measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:656-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sun Y, Christensen J, Hviid A, Li J, Vedsted P, Olsen J, Vestergaard M. Risk of febrile seizures and epilepsy after vaccination with diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, inactivated poliovirus, and Haemophilus influenzae type B. JAMA. 2012;307:823-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jacobsen SJ, Ackerson BK, Sy LS, Tran TN, Jones TL, Yao JF, Xie F, Cheetham TC, Saddier P. Observational safety study of febrile convulsion following first dose MMRV vaccination in a managed care setting. Vaccine. 2009;27:4656-4661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hak E, Bonten MJ. MMR vaccination and febrile seizures. JAMA. 2004;292:2083; author reply 2083-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stehr-Green P, Radke S, Kieft C, Galloway Y, McNicholas A, Reid S. The risk of simple febrile seizures after immunisation with a new group B meningococcal vaccine, New Zealand. Vaccine. 2008;26:739-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Leroy Z, Broder K, Menschik D, Shimabukuro T, Martin D. Febrile seizures after 2010-2011 influenza vaccine in young children, United States: a vaccine safety signal from the vaccine adverse event reporting system. Vaccine. 2012;30:2020-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Habib Z, Akram S, Ibrahim S, Hasan B. Febrile seizures: factors affecting risk of recurrence in Pakistani children presenting at the Aga Khan University Hospital. J Pak Med Assoc. 2003;53:11-17. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Hon KL, Nelson EA. Gender disparity in paediatric hospital admissions. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35:882-888. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Al-Khathlan NA, Jan MM. Clinical profile of admitted children with febrile seizures. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2005;10:30-33. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Jones T, Jacobsen SJ. Childhood febrile seizures: overview and implications. Int J Med Sci. 2007;4:110-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Chan D, Shah PB S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL