Published online Feb 8, 2016. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v5.i1.112

Peer-review started: March 26, 2015

First decision: June 3, 2015

Revised: August 6, 2015

Accepted: October 16, 2015

Article in press: October 17, 2015

Published online: February 8, 2016

Processing time: 309 Days and 13.8 Hours

AIM: To investigate grandparent’s knowledge and awareness about the oral health of their grandchildren.

METHODS: Grandparents accompanying patients aged 4-8 years, who were living with their grandchildren and caring for them for a major part of the day, when both their parents were at work were included in the study. A 20-item questionnaire covering socio-demographic characteristics, dietary and oral hygiene practices was distributed to them. The sample comprised of 200 grandparents (59 males, 141 females). χ2 analysis and Gamma test of symmetrical measures were applied to assess responses across respondent gender and level of education.

RESULTS: Oral health related awareness was found to be low among grandparents. In most questions asked, grandparents with a higher level of education exhibited a better knowledge about children's oral health. Level of awareness was not related to their gender.

CONCLUSION: Oral hygiene and dietary habits are established during childhood. There is a great need for dental education of grandparents as they serve as role models for young children.

Core tip: An observational study evaluating the attitude and knowledge of grandparents as they serve an important role as caregivers in their grandchildren’s lives. There is a great need for dental education of grandparents as they serve as role models for the young.

- Citation: Oberoi J, Kathariya R, Panda A, Garg I, Raikar S. Dental knowledge and awareness among grandparents. World J Clin Pediatr 2016; 5(1): 112-117

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v5/i1/112.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i1.112

With changing family patterns, increased life expectancy, growing numbers of dual-worker households and higher rates of family breakdown, grandparents are now playing an increasing role in their grandchildren’s lives[1-3]. Grandparents are an important resource for both parents and children. They routinely provide child care, financial assistance and emotional support. Occasionally they are called upon to provide much more, including temporary or full time care and responsibility for their grandchildren. Child and adolescent psychiatrists recognize the important role many grandparents play in raising their grandchildren[1].

The changing role of grandparents in society has led to a greater responsibility on them as nurturers, mentors, and teachers and they also play a crucial part in modelling a good lifestyle for the child. Moreover, in everyday life, grandparents function as role models for their grandchildren, and therefore, grandparents’ knowledge, awareness and dental hygiene practises may play an important role in influencing children’s behaviour and attitude towards good oral health care. Hence, in order to improve children’s oral health status, grandparents should be considered as one of the key people involved in and influencing children’s lives and the health care that they receive. A considerable amount of research dealing with the role that parents[4,5] (and mothers in particular)[6,7] play in influencing the oral health status of children has been done, but there is dearth of literature investigating the role grandparents play in influencing children’s oral health status. A review of literature revealed only one study[8], where knowledge of caregivers, which included grandparents (107 grandparents out of 615 caregivers, i.e., 17.4%) was studied. Thus, this study was carried out to investigate the knowledge, awareness, beliefs and practises of grandparents related to their grandchildren’s oral health.

Before the start of the study, the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Dr. D.Y. Patil Dental College and Hospital, Navi Mumbai. A questionnaire was prepared to assess the knowledge and awareness of grandparents regarding the oral health of their grandchildren. Grandparents accompanying patients aged 4-8 years attending the outpatient department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry of the Dr. D.Y. Patil Dental College and Hospital, Navi Mumbai, who were living with their grandchildren and caring for them for a major part of the day, when both their parents were at work, were explained the purpose of the study. Participation in the study was voluntary. The grandparents who volunteered to take part in the study and signed a consent form, were distributed the questionnaires in the waiting area of the outpatient department. The questionnaire was translated into a local language for ease of understanding. The questionnaire was read for the grandparents who could not read and their answers were recorded. The questionnaires were completed in the waiting area prior to the patient’s appointments. The questionnaire comprised of 20 questions and the participants were asked to select one appropriate option for each question. The demographic information collected from the questionnaire included age of the grandchild, and gender and educational qualification of the grandparent. Literature was consulted regarding the knowledge of mothers/parents in regard to their children’s dental health and the existing questions were adapted for this survey[4-8]. A pilot study was conducted by asking 20 grandparents and members of staff to complete the questionnaire. The feedback was positive but indicated that use of the terms “pedodontists” and “malocclusion” was causing some confusion. As a result, these were replaced with “pediatric dentists” and “crooked teeth” respectively, to improve understanding. Completed questionnaires were collected and passed blind to an independent statistician where they were analysed for response frequency and the results tabulated. The statistical analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., version 15.0 for Windows). Descriptive statistics and χ2 analysis for non-parametric data with the appropriate degrees of freedom were performed on the data to assess responses to the questionnaire items across respondent gender and level of education. In addition, Gamma test of Symmetrical Measures was also applied for analysis across education levels. Statistical significance was determined at P≤ 0.05.

A total of 200 grandparents participated in the study. Out of these 141 (70.5%) were females and 59 (29.5%) were males. Out of 200 grandparents, 40 (20%) were illiterate and 114 (57%) had up to higher secondary education. The number of grandparents having graduate and post graduate qualifications, was 38 (19.0%) and 8 (4%) respectively. The results were analysed on the basis of gender and level of education.

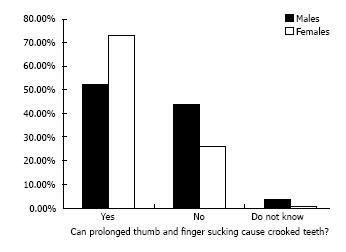

Statistically significant difference (P≤ 0.05) between genders was seen only in one question, that is, female grandparents (73%) were more aware than their male counterparts (52.5%) that prolonged sucking habits could result in malocclusion (Figure 1). In all other questions, the difference seen between the responses of both the genders was statistically insignificant.

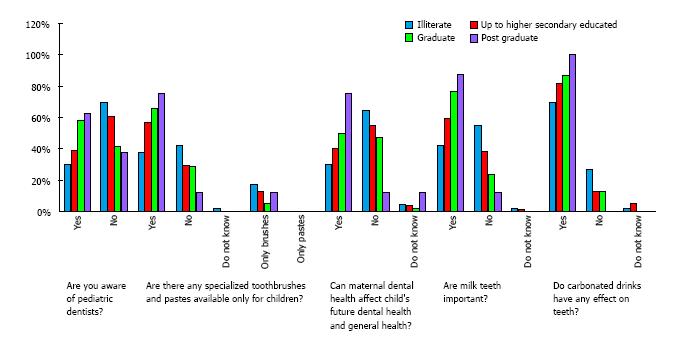

When response of the grandparents was compared to the level of education, a higher level of awareness was positively correlated with a higher level of education but not in all questions and not consistent with the increase in the level of education. Statistically significant difference (P≤ 0.05) between different levels of education was seen in five questions (Figure 2). When asked whether they were aware of paediatric dentists, 30%, 39.5%, 57.9% and 62.5% of illiterates (henceforth referred to as category I), higher secondary educated (henceforth referred to as category II), graduates (henceforth referred to as category III) and post graduates (henceforth referred to as category IV) respectively (total 42%), replied in the affirmative (statistically significant) (Figure 2). A total of 51% grandparents (47.5%, 48.2%, 60.5% and 62.5% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively), thought frequent visits to the dentist were important. When asked whether they had ever tried to treat the child for any dental related problem at home, 35%, 30.7%, 23.7% and 50% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively, replied in the affirmative (total 31%). Majority (67%) of the grandparents (65%, 64.9% 68.4% and 100% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) said that prolonged thumb and finger sucking can cause crooked teeth. A vast majority (88.5%) of the grandparents (92.5%, 84.2%, 94.7% and 100% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) knew that brushing teeth could prevent dental problems. Regarding the availability of specialized toothbrushes and pastes only for children, 37.5%, 57%, 65.8% and 75% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively, were aware of the same (statistically significant) (Figure 2), whereas 17.5%, 13.1%, 5.3% and 12.5% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively, were aware only of specialized brushes for children and not of pastes. A majority (78.5%) of grandparents (65%, 81.6%, 78.9% and 100% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) said that they gave as much importance to the care of their teeth as to other parts of their body. When asked whether maternal dental health could affect child’s future dental health and general health, only 30%, 40.4%, 50% and 75% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively, replied in the affirmative (statistically significant) (Figure 2). Many of the grandparents were also unaware of the age at which the first dental check up of the child should be done. Only 17.5%, 11.4%, 7.9% and 37.5% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively, said that the first dental checkup should be at or before 1 year of age (total 13%), whereas the rest of the grandparents gave varied answers like 2 years (20.5%), 3 years (13%), after 4 years (20.5%) and when required (33%). The high level of unawareness was also evident by the responses to the question about when one should start brushing the child’s teeth. A total of 27.5% grandparents (22.5%, 23.7%, 42.1%, and 37.5% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) said that brushing should be started at or before 1 year of age, whereas others gave varied answers like 2 years (31%), 3 years (25.5%), after 4 years (14.5%) and do not know (1.5%). Most of the grandparents were well aware of the total number of permanent teeth with 87.5%, 79.8%, 84.2% and 100% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively giving the answer as 32, but most were not aware of the number of milk teeth with only 7.5%, 15.8%, 13.1% and 50% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively (total 15%), giving the answer as 20. A total of 60.5% grandparents (42.5%, 59.6%, 76.3% and 87.5% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) said that milk teeth were important (statistically significant) (Figure 2), whereas a total of 47.5% grandparents (45%, 38.6%, 68.4% and 87.5% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) said that problems of milk teeth could affect permanent teeth. Only 36% of grandparents (37.5%, 28.9%, 50% and 62.5% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) knew that dental decay could be transmitted by sharing of spoons and cups. When asked whether prolonged bottle or breast feeding could affect dental health, 49.5% grandparents (47.5%, 45.6%, 60.5% and 62.5% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) replied in the affirmative. A total of 32.5% grandparents (40%, 33.3%, 28.9% and 0% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) said that it was alright to put children to bed with a bottle. A total of 36.5% of grandparents (37.5%, 28.9%, 50% and 75% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) said that use of fluorides could strengthen teeth. A vast majority (81%) of grandparents (70%, 81.6%, 86.8% and 100% of categories I, II, III, and IVrespectively) knew that carbonated drinks had ill effects on teeth (statistically significant) (Figure 2). A vast majority (95%) of grandparents (100%, 93.8%, 92.1% and 100% of categories I, II, III, and IV respectively) also knew that frequent snacking of sweet and sticky foods had ill effects on the teeth.

In the present study, the sample selected was dominated by female grandparents (70.5%) and a majority of the grandparents fell in the up to higher secondary educated group (57%). To the best of our knowledge no other study has been done to evaluate the level of dental awareness among grandparents, so a direct comparison of the above findings was not possible. In this study it was seen that the level of awareness about oral health was low among grandparents. A majority of them were not aware about paediatric dentists or specialized dentists for children. Awareness about the same was higher in the more educated groups but even among the post graduates, many were not aware of the same. There was no significant difference found between the genders. The grandparents were also not aware about the importance of frequent visits to the dentist so that any decay or condition can be recognized and rectified at an early stage. This indicates that there is an immediate and great need for education of caregivers like grandparents. The importance of such facts needs to be emphasized by paediatricians who see children at regular intervals or for vaccinations. Alternatively nurses can also be trained to impart this information in paediatric and vaccination wards of hospitals so that it can have an impact on maximum people.

When asked whether they had tried to treat their grandchildren at home with home remedies, the results obtained were surprising. It was found that people who were illiterates were in the habit of taking the children to a dentist whereas 50% of the postgraduates had tried their hand at treating the child themselves. People need to be educated that they should not try to treat children themselves, especially when the child cannot be relied upon to explain the symptoms correctly due to young age and lack of previous experience of dental pain. Children’s understanding of pain and their ability to describe it changes in a predictable developmental sequence[9]. As the experience of pain is inherently personal and subjective, it is not directly accessible to others and requires considerable judgment and skill on the part of observers in the use of cues that are available, if inferences are to be accurate[10]. It should be stressed to the caregivers that they should always consult a specialist and not try to treat the children themselves as this may lead to wastage of precious time and the child may have to bear consequences that are permanent and irrevocable.

The grandparents showed good knowledge about the harmful effects of prolonged sucking habits. The female grandparents were much more aware about the same than their male counterparts, the difference being statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). The reason for this can be that as females are more aesthetically oriented[11] and spend more time looking after and caring for their grandchildren, they may notice little changes in the facial structure that occur during the growing up stages of the child.

When the responses of the same question were compared with the level of education, the surprising result was that the level of awareness was the same in the illiterates, up to higher secondary educated and the graduates (65%) but jumped to 100% in the postgraduates. The reason for this could be that the postgraduates, because of higher level of knowledge and understanding, probably come in contact with information from different sources such as media and newspapers, books and internet and hence, are more aware. The awareness about the deleterious effects of prolonged sucking habits need to be imparted to everybody so that such habits can be stopped before they have any effect on the oral structures.

The knowledge about the advantages of regular brushing was very good across genders and at all levels of education, probably because of the role of media in promoting tooth brushes. The awareness about specialized toothbrushes and pastes for children need to be improved, especially in caregivers of young children as children below 2 years of age should not be given fluoridated toothpastes, unless considered at moderate or high caries risk[12] and such small children won’t be able to manoeuvre an adult brush in their small mouths. This can be achieved through the use of broadcast media, such as televisions. Another important source of information can be pharmacists who can help promote these by giving information to customers, especially as old people are likely to visit them more.

A majority of grandparents did not know about the transmission of cariogenic bacteria from mothers to their children[13,14], and the fact that it could increase the risk and severity of caries in very young children[15,16]. This knowledge was higher in the groups with a higher level of education but even among the well educated grandparents, a considerable proportion was not aware of the same (Figure 2). To improve this, workshops/lectures can be started in community centres or in places like meditation centres, laughter clubs, societies and book clubs etc. which are routinely frequented by the aged. Regarding the awareness about the appropriate age for the first dental visit and the age to start brushing the child’s teeth, mixed results were obtained and no particular trend was followed. This shows that even people who have the highest level of education are not aware about basic and important health recommendations while caring for a child. Again the paediatrician or the nurses at hospitals and vaccination centres can help in spreading awareness about the same. Caretakers should be educated that regular tooth cleaning needs to be started early in life, as soon as the first primary tooth erupts[12].

Most grandparents knew about the number of permanent teeth in the mouth but not about the primary teeth. This could be due to the age old myth that as milk teeth are ultimately going to fall off, they are not important. A large number of the grandparents even acknowledged that they did not consider primary teeth to be of any importance and that they did not think that problems of primary teeth could affect permanent teeth. This misconception leads to neglect of the child’s oral health by caregivers and because of bad habits instilled early in life, such children grow up to be adults who do not take good care of their teeth. The importance of primary teeth needs to be emphasized by paediatricians and general dentists so that this mindset can be changed. It has been reported in previous studies[17,18] that the low value attributed to primary teeth is an obstacle to developing effective prevention programs.

The practice of sharing foods and utensils by adults has been associated with early infection with Streptococcus mutans in infants[19,20]. Grandparents are often in the habit of checking the temperature of the food before giving it to the child by tasting it. This can be harmful as it can introduce caries causing microorganisms into the child’s mouth if the same spoon or cup is used. Grandparents need to be educated about the harmful effects of such practices which they consider normal and routine.

Majority of the grandparents did not know about the harmful effects of prolonged bottle or breast feeding or the advantages of fluorides. Awareness of the same was more in the higher educated but not consistently or significantly. Knowledge about the deleterious effects of putting a child to bed with a bottle and use of carbonated drinks by older children was more in the higher educated grandparents (Figure 2).

There is a great need for education of grandparents regarding their grandchildren’s oral health. This can be done by holding demonstrations and lectures/workshops in community centres. Also small demonstrations can be prepared and delivered in waiting areas of hospitals, nursing homes and dental clinics by volunteers or small documentaries can be made for televisions which are repeatedly played in the waiting area. Also nurses and other health personnel can be trained to impart information in vaccination centres. Paediatricians can also help in imparting information and guidance when the child is brought for any treatment. Posters regarding oral health related facts about children can be put up in paediatric wards and dental clinics/vaccination centres. All these measures can improve the preventive dental care children receive at home and their use of professional dental services, ultimately, bringing us closer to our international oral health goals for children.

In today’s changing society where both parents are working, grandparents assume an important role as caregivers in their grandchildren’s lives. There is a great need for dental education of grandparents as they serve as role models for the young. The attitude and knowledge of grandparents was evaluated in this study so as to implement changes to improve the oral hygiene standard of children.

To the best of our knowledge, no such study has been done where only grandparents were evaluated for the role that they play in influencing children’s oral health status. A review of literature revealed only one study where knowledge of caregivers, which included grandparents (107 grandparents out of 615 caregivers, i.e., 17.4%) was studied. It has been seen that improving the knowledge of mothers has a positive influence on the children’s oral health status.

The major conclusion from the article is that there is a great need for education of grandparents regarding their grandchildren’s oral health. Since a lot of grandparents are playing a major role in caring for the children while both their parents are working, steps must be taken to ensure that they know how to take care of the oral hygiene of the children. Till now, major stress was given in imparting this knowledge to only parents, especially mothers.

To eliminate any disease, the first step is to gain knowledge of how that disease is contracted. Since dental caries cannot be reversed, to control it, we need to prevent its onset. This can only be done by maintaining proper oral hygiene. If children are educated about the value of maintaining proper oral hygiene, good habits can be instilled in them from a young age. Since grandparents play a big role in taking care of the children and serve as role models for them, they need to be educated about how to take care of their grandchild’s oral health.

Streptococcus mutans is facultative anaerobic, Gram-positive coccus-shaped bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity and is a significant contributor to tooth decay.

An interesting article that provides a different perspective to the prevention of dental caries. It shows how caretakers need to be educated if we want the next generation to be free of oral diseases.

P- Reviewer: Sergi CM S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Grandparents Raising Grandchildren. Facts for Families. Available from: http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/Facts_for_families_Pages/Grandparents_Raising_Grandchildren_77.aspx. |

| 2. | Chen F, Liu G, Mair CA. Intergenerational Ties in Context: Grandparents Caring for Grandchildren in China. Soc Forces. 2011;90:571-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Luo Y, LaPierre TA, Hughes ME, Waite LJ. Grandparents Providing Care to Grandchildren: A Population-Based Study of Continuity and Change. J Fam Issues. 2012;33:1143-1167. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Adair PM, Pine CM, Burnside G, Nicoll AD, Gillett A, Anwar S, Broukal Z, Chestnutt IG, Declerck D, Ping FX. Familial and cultural perceptions and beliefs of oral hygiene and dietary practices among ethnically and socio-economicall diverse groups. Community Dent Health. 2004;21:102-111. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mattila ML, Rautava P, Ojanlatva A, Paunio P, Hyssälä L, Helenius H, Sillanpää M. Will the role of family influence dental caries among seven-year-old children? Acta Odontol Scand. 2005;63:73-84. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Saied-Moallemi Z, Virtanen JI, Ghofranipour F, Murtomaa H. Influence of mothers’ oral health knowledge and attitudes on their children’s dental health. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2008;9:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dye BA, Vargas CM, Lee JJ, Magder L, Tinanoff N. Assessing the relationship between children’s oral health status and that of their mothers. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:173-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chan SC, Tsai JS, King NM. Feeding and oral hygiene habits of preschool children in Hong Kong and their caregivers’ dental knowledge and attitudes. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:322-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Versloot J, Craig KD. The communication of pain in paediatric dentistry. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;10:61-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chapman BP, Duberstein PR, Sörensen S, Lyness JM. Gender Differences in Five Factor Model Personality Traits in an Elderly Cohort: Extension of Robust and Surprising Findings to an Older Generation. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43:1594-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shearer DM, Thomson WM. Intergenerational continuity in oral health: a review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:479-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, Clinical Affairs Committee--Infant Oral Health Subcommittee. Guideline on infant oral health care. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:148-152. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Li Y, Caufield PW. The fidelity of initial acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants from their mothers. J Dent Res. 1995;74:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Douglass JM, Li Y, Tinanoff N. Association of mutans streptococci between caregivers and their children. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:375-387. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Boggess KA, Edelstein BL. Oral health in women during preconception and pregnancy: implications for birth outcomes and infant oral health. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:S169-S174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Law V, Seow WK, Townsend G. Factors influencing oral colonization of mutans streptococci in young children. Aust Dent J. 2007;52:93-100; quiz 159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Riedy CA, Weinstein P, Milgrom P, Bruss M. An ethnographic study for understanding children’s oral health in a multicultural community. Int Dent J. 2001;51:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Harrison RL, Wong T. An oral health promotion program for an urban minority population of preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:392-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Newbrun E. Preventing dental caries: breaking the chain of transmission. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:55-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sakai VT, Oliveira TM, Silva TC, Moretti AB, Geller-Palti D, Biella VA, Machado MA. Knowledge and attitude of parents or caretakers regarding transmissibility of caries disease. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008;16:150-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |