Published online Nov 8, 2015. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v4.i4.155

Peer-review started: May 9, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Revised: July 23, 2015

Accepted: August 13, 2015

Article in press: August 14, 2015

Published online: November 8, 2015

Processing time: 186 Days and 0.8 Hours

AIM: To review the experience in the management of impalpable testes using laparoscopy as the initial approach and the need for inguinal exploration.

METHODS: From January 2004 to June 2014, 339 patients with undescended testes underwent operation in our institute. Fifty patients (15%) had impalpable testes. All children with impalpable testes underwent initial laparoscopy. A retrospective review was conducted on this group of patients and the outcome was analyzed.

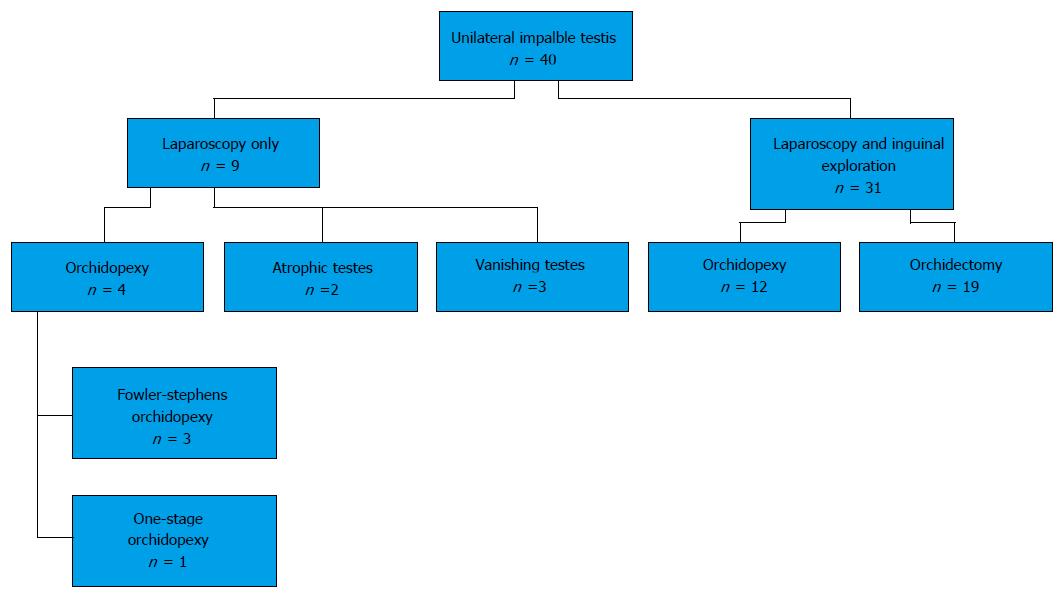

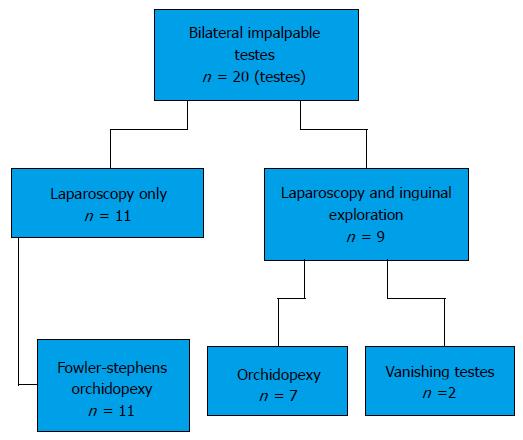

RESULTS: Forty children had unilateral impalpable testis. Ten children had bilateral impalpable testes. Thirty-one children (78%) in the unilateral group underwent subsequent inguinal exploration while 4 children (40%) in the bilateral group underwent inguinal exploration (P < 0.05). Orchidopexy was performed in 16 children (40%) in the unilateral group and 9 children (90%) in the bilateral group (P < 0.05). Regarding the 24 children with unilateral impalpable testis and underwent orchidectomy for testicular nubbin (n = 19) or atrophic testes (n = 2) or has vanishing testes (n = 3); contralateral testicular hypertrophy was noticed in 10 (41%). No intra-operative complication was encountered. Two children after staged Fowler-Stephens procedure and 1 child after inguinal orchidopexy had atrophic testes.

CONCLUSION: The use of laparoscopy in children with impalpable testes is a safe procedure and can guide the need for subsequent inguinal exploration. Children with unilateral impalpable testis were associated with an increased need for inguinal exploration after laparoscopy. Orchidopexies could be performed successfully in 90% of children with bilateral impalpable testes.

Core tip: Among over 300 children with undescended testis underwent operation, 15% of children had impalpable testis. The review studies the use of laparoscopy as the initial management of children with impalpable testes. Compared with children with bilateral impalpable testes, children with unilateral impalpable testis had an increased need for subsequent inguinal exploration and a lower incidence of successful orchidopexy. Laparoscopy is a safe procedure with no intra-operative complication encountered in this study.

- Citation: Chan KWE, Lee KH, Wong HYV, Tsui SYB, Wong YS, Pang KYK, Mou JWC, Tam YH. Use of laparoscopy as the initial surgical approach of impalpable testes: 10-year experience. World J Clin Pediatr 2015; 4(4): 155-159

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v4/i4/155.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v4.i4.155

Cryptorchidism is a common pediatric surgical condition that affected 2%-5% of new born[1]. If left untreated, cryptorchidism poses risk in malignancy and infertility[1-4]. In a child with a palpable testis at inguinal region, orchidopexy is recommended to be performed at 6-12 mo-of-age if spontaneous descend of the testis does not occurred by 6 mo-of-age[3]. On the other hand, in a child with an impalpable testis, ultrasonography of the inguinal canal is required locate the testis in pre-operative evaluation[4].

In the era of minimally invasive surgery, laparoscopy was advocated as the initial surgical approach in children with impalpable testes[5-8]. Laparoscopy can confirm the presence or absence of intra-abdominal testes and can direct the subsequent approach. However, others suggested that inguinal or scrotal exploration should be used as the initial approach in children with unilateral impalpable testis[9-11].

In our institute, all children with impalpable testes underwent initial laparoscopy. This study aimed to study the outcome of children using this approach.

From January 2004 to June 2014, 339 boys with undescended testes underwent operation in our institute. Fifty children (15%) had impalpable testes. Impalpable testis was defined as the testis was not palpable under general anesthesia. The median age for children at the time of operation with impalpable testis was 26 mo (range: 8-192 mo). They all underwent laparoscopy as the initial procedure.

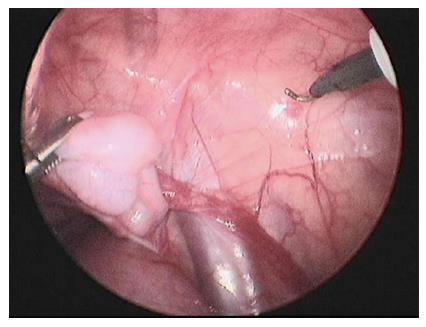

All patients were examined again under general anesthesia and confirmed the diagnosis of impalpable testes. A sub-umbilical incision was made and a 5 mm 30 degree laparoscope was used. If the testis was identified intra-abdominally (Figure 1), two 3 or 5 mm ports were inserted over the abdomen; either one-stage laparoscopic or two-staged laparoscopic Fowler-Stephens orchidopexy was performed. If a blind ended vas was located away from the deep ring, the testis was defined vanished. If both vas and testicular vessels entered into the deep ring (Figure 2), an inguinal exploration was then performed. Inguinal orchidopexy was performed for normal looking testis. If a testicular nubbin or an atrophic testis was identified, it would be excised and sent for histological examination. For peeping testis, orchidopexy was performed by either inguinal or laparoscopic approach, depending on the surgeon’s preference.

The age of the patients, the laterality of the testes, the presence of any contralateral testicular hypertrophy on physical examination, the laparoscopic findings and the need for inguinal exploration, the incidence of orchidopexy and any intraoperative and post-operative complication were reviewed.

Statistical analysis was accomplished using the SPSS program for Windows 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, United States). Fisher exact test was used to compare the categorical data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Yuk Him Tam from the Prince of Wales Hospital.

Forty children had unilateral impalpable testis. Ten children had bilateral impalpable testes. Orchidopexy was performed in 16 children (40%) in the unilateral group and 9 children (90%) in the bilateral group (P < 0.05) (Figures 3 and 4).

Regarding the 16 children who underwent orchidopexy, 12 children underwent inguinal orchidopexy (5 peeping testes), 3 children underwent Fowler-Stephens operation (1 peeping testis) and 1 child underwent laparoscopic one stage orchidopexy. Twenty-one children have “orchidectomy” performed for the testicular nubbin (n = 19) or atrophic testis (n = 2). Three children had vanishing testes. Out of the 24 children who underwent orchidectomy or has vanishing testes, contralateral testicular hypertrophy was noticed in 10 children (41%). Children with left impalpable testis has a lower rate of orchidopexy (L: 35%, 9/17, R: 50%, 7/7), However the difference did not reach statistical significant (Figure 3, Tables 1 and 2).

| Unilateral impalpable testisn = 40 | Bilateral impalpable testisn = 10 | P value | ||

| Inguinal exploration | Required | 31 | 4 | 0.03 |

| Not required | 9 | 6 | ||

| Orchidopexy | Performed | 16 | 9 | 0.005 |

| Not performed | 24 | 1 | ||

| Leftn = 26 | Rightn = 14 | P value | ||

| Inguinal exploration | Required | 22 | 9 | 0.14 |

| Not required | 4 | 5 | ||

| Orchidopexy | Performed | 9 | 7 | 0.27 |

| Not performed | 17 | 7 | ||

Orchidopexy were performed in 18 testes (90%). Inguinal orchidopexy was performed in 7 testes. Fowler–Stephens procedure was performed in 11 testes. One child had bilateral vanishing testes upon inguinal exploration (Figure 4).

Thirty-one children (78%) in the unilateral group underwent subsequent inguinal exploration while only 4 children (40%) in the bilateral group underwent groin exploration (P < 0.05). In the unilateral group, children with left impalpable testis had a higher need for inguinal exploration (L: 85%, 22/26, R: 64%, 9/14) but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Tables 1 and 2).

No intraoperative complication was encountered. Histological examination showed absence of testicular tissue in all the nubbins. Benign testicular tissues were identified in the 2 atrophic testes. The mean follow up was 53 mo (range 10 to 198 mo). Testicular atrophy was noticed in 2 children after 2nd stage Fowler-Stephen procedure and 1 child after inguinal orchidopexy.

There is ongoing debate on the best initial approach for impalpable testis. Our study showed in children with unilateral impalpable testis, 78% of children required an inguinal incision. In reports which used laparoscopy as the initial approach for impalpable testes, the need for inguinal or scrotal exploration for unilateral impalpable testis ranged from 38% to 85%[12,13]. Ethnic, geographic and genetic reasons may account for the difference in the incidence of intra-abdominal testes in children with impalpable testes[13-15]. Although a high proportion of children with unilateral impalpable testes required an inguinal incision, initial laparoscopy directed the subsequent approach without any intraoperative complication encountered in this study.

Regarding the laterality of the unilateral impalpable testis, the testis was more commonly located on the left side (65%). Eighty-five percent of children with left impalpable testis had inguinal exploration while only 64% of children with right impalpable testis had inguinal exploration. Park et al[16] had similar finding in their study but other studies did not report the laterality of the testes[7,8]. In children with bilateral impalpable testes, only 40% of children in this study required additional inguinal exploration. Sixty-five percent (13/20) of testes can be managed by laparoscopy alone, including 2 vanishing testes.

Fifty three percent of children with unilateral impalpable testis underwent orchidectomy. Majority of children had either a testicular nubbin or a vanishing testis. Intrauterine loss was the postulated etiology in children with unilateral impalpable testis[17]. Studies showed if contralateral testicular size larger than 1.8 cm predict testicular loss on the symptomatic side[11,17]. In this study, we used subjective manual assessment, which may not be as accurate as the measurement by ultrasonography. Although only 41% of children with unilateral testicular loss showed contralateral testicular hypertrophy, this physical finding can provide additional information in pre-operative counseling.

Germ cell was reported to be present in up to 16% of the testicular nubbin specimen[18]. In this study, pathological study of the testicular nubbin did not detect any testicular tissue. We think it is still a reasonable approach the removed the nubbin in order to confirm the histology.

The success rate after laparoscopic assisted orchidopexy was 87% (13/15). There were reports studying the success rate of different laparoscopic approaches including one-stage laparoscopic repair, one-stage Fowler-Stephens or two-stage Fowler-Stephens repair[19-21]. The assessment on the feasibility of one stage laparoscopic repair may be difficult. Two-stage Fowler-Stephens orchidopexy may be the treatment of choice for all intra-abdominal testes, if there was any doubt in decision of the laparoscopic approach intra-operatively[22].

One of the limitations of this study is on the decision of surgical approach in peeping testis. Five out of 6 peeping testes were managed by inguinal orchidopexy. Both inguinal and laparoscopic approaches were effective in the management of peeping testis[23]. Our approach increased the number of inguinal exploration in this study.

In the era of minimally invasive surgery, laparoscopy was advocated as the initial approach in children with impalpable testes. Laparoscopy can confirm the presence or absence of intra-abdominal testes and can direct the subsequent approach.

Controversies still exist on the best initial approach in the management of impalpable testis. Others suggested that inguinal or scrotal exploration should be used as the initial approach in children with unilateral impalpable testis.

This study showed in children with unilateral impalpable testis, 78% of children required an inguinal incision. Orchidopexies could be performed successfully in 90% of children with bilateral impalpable testes.

Laparoscopy is a safe procedure with no intra-operative complication encountered in this study. A prospective study is needed to study the best initial approach in unilateral impalpable testis.

Cryptorchidism: Impalpable testis or undescended testis. Impalpable testis: The testis is not palpable in scrotum or at groin after general anesthesia. First stage Fowler-Stephens operation: Division of the testicular vessels which aids the development of collateral vessels along the vas deferens. Second stage Fowler-Stephens operation: Mobilization of the testis into the scrotum.

This is a retrospective study of 50 children with impalpable testes who have been managed by laparoscopy as the initial treatment and perhaps the initial diagnostic procedure as well. The paper is well written and the messages are clear.

| 2. | Chan E, Wayne C, Nasr A. Ideal timing of orchiopexy: a systematic review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30:87-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thomas RJ, Holland AJ. Surgical approach to the palpable undescended testis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30:707-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vos A, Vries AM, Smets A, Verbeke J, Heij H, van der Steeg A. The value of ultrasonography in boys with a non-palpable testis. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1153-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cisek LJ, Peters CA, Atala A, Bauer SB, Diamond DA, Retik AB. Current findings in diagnostic laparoscopic evaluation of the nonpalpable testis. J Urol. 1998;160:1145-1149; discussion 1150. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Baker LA, Docimo SG, Surer I, Peters C, Cisek L, Diamond DA, Caldamone A, Koyle M, Strand W, Moore R. A multi-institutional analysis of laparoscopic orchidopexy. BJU Int. 2001;87:484-489. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sheikh A, Mirza B, Ahmad S, Ijaz L, Kayastha K, Iqbal S. Laparoscopic management of 128 undescended testes: our experience. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2012;9:106-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Papparella A, Parmeggiani P, Cobellis G, Mastroianni L, Stranieri G, Pappalepore N, Mattioli G, Esposito C, Lima M. Laparoscopic management of nonpalpable testes: a multicenter study of the Italian Society of Video Surgery in Infancy. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:696-700. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kanemoto K, Hayashi Y, Kojima Y, Tozawa K, Mogami T, Kohri K. The management of nonpalpable testis with combined groin exploration and subsequent transinguinal laparoscopy. J Urol. 2002;167:674-676. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Snodgrass W, Chen K, Harrison C. Initial scrotal incision for unilateral nonpalpable testis. J Urol. 2004;172:1742-1745; discussion 1745. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Snodgrass WT, Yucel S, Ziada A. Scrotal exploration for unilateral nonpalpable testis. J Urol. 2007;178:1718-1721. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Castillo-Ortiz J, Muñiz-Colon L, Escudero K, Perez-Brayfield M. Laparoscopy in the surgical management of the non-palpable testis. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ueda N, Shiroyanagi Y, Suzuki H, Kim WJ, Yamazaki Y, Tanaka Y. The value of finding a closed internal ring on laparoscopy in unilateral nonpalpable testis. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:542-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Papparella A, Romano M, Noviello C, Cobellis G, Nino F, Del Monaco C, Parmeggiani P. The value of laparoscopy in the management of non-palpable testis. J Pediatr Urol. 2010;6:550-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Abbas TO, Hayati A, Ismail A, Ali M. Laparoscopic management of intra-abdominal testis: 5-year single-centre experience-a retrospective descriptive study. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;2012:878509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Park JH, Park YH, Park K, Choi H. Diagnostic laparoscopy for the management of impalpable testes. Korean J Urol. 2011;52:355-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Belman AB, Rushton HG. Is the vanished testis always a scrotal event? BJU Int. 2001;87:480-483. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Renzulli JF, Shetty R, Mangray S, Anderson KR, Weiss RM, Caldamone AA. Clinical and histological significance of the testicular remnant found on inguinal exploration after diagnostic laparoscopy in the absence of a patent processus vaginalis. J Urol. 2005;174:1584-1586; discussion 1586. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Mehendale VG, Shenoy SN, Shah RS, Chaudhari NC, Mehendale AV. Laparoscopic management of impalpable undescended testes: 20 years’ experience. J Minim Access Surg. 2013;9:149-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alzahem A. Laparoscopy-assisted orchiopexy versus laparoscopic two-stage fowler stephens orchiopexy for nonpalpable testes: Comparative study. Urol Ann. 2013;5:110-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Singh RR, Rajimwale A, Nour S. Laparoscopic management of impalpable testes: comparison of different techniques. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:1327-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Burjonrappa SC, Al Hazmi H, Barrieras D, Houle AM, Franc-Guimond J. Laparoscopic orchidopexy: the easy way to go. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:2168-2172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Elderwy AA, Kurkar A, Abdel-Kader MS, Abolyosr A, Al-Hazmi H, Neel KF, Hammouda HM, Elanany FG. Laparoscopic versus open orchiopexy in the management of peeping testis: a multi-institutional prospective randomized study. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10:605-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Eric M, Golffier C, Lee ACW S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK