Published online Feb 8, 2015. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v4.i1.1

Peer-review started: November 4, 2014

First decision: November 21, 2014

Revised: December 6, 2014

Accepted: December 16, 2014

Article in press: December 17, 2014

Published online: February 8, 2015

Processing time: 92 Days and 4.5 Hours

Complicated migraine encompasses several individual clinical syndromes of migraine. Such a syndrome in children frequently presents with various neurological symptoms in the Emergency Department. An acute presentation in the absence of headache presents a diagnostic challenge. A delay in diagnosis and treatment may have medicolegal implication. To date, there are no reports of a common clinical profile proposed in making a clinical diagnosis for the complicated migraine. In this clinical review, we propose and describe: (1) A common clinical profile in aid to clinical diagnosis for spectrum of complicated migraine; (2) How it can be used in differentiating complicated migraine from migraine without aura, migraine with aura, and seizure; (3) We discuss the status of complicated migraine in the International Headache Society classification 2013; and (4) In addition, a common treatment strategy for the spectrum of migraine has been described. To diagnose complicated migraine clinically, it is imperative to adhere with the proposed profile. This will optimize the use of investigation and will also avoid a legal implication of delay in their management. The proposed common clinical profile is incongruent with the International Headache Society 2013. Future classification should minimize the dissociation from clinically encountered syndromes and coin a single word to address collectively this subtype of migraine with an acute presentation of a common clinical profile.

Core tip: Complicated migraine in pediatric neurology practice is a frequent cause for an Emergency Department visit. Their clinical presentations are variable. They mimic several clinical syndromes but they can be diagnosed clinically by following proposed common clinical profile closely in the absence of any identifiable etiology.

- Citation: Gupta SN, Gupta VS, Fields DM. Spectrum of complicated migraine in children: A common profile in aid to clinical diagnosis. World J Clin Pediatr 2015; 4(1): 1-12

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v4/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v4.i1.1

Most practicing clinicians have acquired knowledge in making a clinical diagnosis of migraine with and without aura. Unlike adults, migraines in children are common in Emergency and Ambulatory Care-Settings. When children present with an acute onset neurologic symptom other than headache, hesitancy to diagnose migraine may arise. This is primarily due to lack of realization of a full spectrum of migraines which include migraine without aura, migraine with aura, and complicated migraine. Secondarily, this is due to lack of appreciation that complicated migraine is a “fragmented” presentation of the migraine attack profile. Unlike migraine without aura, complicated migraine is not a single entity. It includes a variety of individual syndromes. In pediatric neurology practice, complicated migraines are the most common cause after seizures for Emergency Department visits. These syndromes are named after their presenting symptoms with an exception to basilar type migraine which defies this rule. Multiple manifestations of basilar type migraine represent its neuroanatomical evolvement.

Migraines are self-limiting dysfunctions of grey matter. It is primarily a neuronal sensory dysfunction which secondarily involves the vascular systems. Involvement of the sensory nerve fibers within meningeal blood vessels gives rise to head pain[1,2].

The diagnosis of complicated migraine is basically clinical. The common differential diagnosis includes seizure, transient ischemic attack, and migraine like syndromes. Their relationships are complex. Migraine and seizure are common conditions and they may coexist in the same patient[3].

In this clinical review, we discuss the status of complicated migraine in the International Headache Society classification, the third Edition 2013. We propose a common clinical profile in making the clinical diagnosis of complicated migraine. We describe clinical characteristics of the proposed profile and how they can be used in differentiating complicated migraine from migraine without aura, migraine with aura, and seizure. In addition, a common treatment strategy for the spectrum of migraine is described.

Multiple terms, complicated migraine, complex migraine, migraine accompanies acephalgic migraine, uncommon migraines, or migraine variants have been used. Some of these, complicated or complex migraine, or migraine accompanies are considered obsolete. However, in clinical practice, as an umbrella-term, the complicated migraine remains useful indicating a common clinical profile for a wide variety of acute neurologic syndromes of unknown etiology.

In this review, we have used the term complicated migraine collectively to express a subgroup of individual clinical syndromes which are distinct from migraine with and without aura.

The individual syndrome of “complicated migraine” is classified by the International Headache Society (IHS) 2013 under the first three out of eleven subheadings of migraine Table 1[4]. This is primarily designed to provide for migraine the diagnostic codes for policymaking or for research. “Complications of the migraine” listed in the IHS classification 2013 should not be confused with complicated migraine. Status migrainosus is a complication of migraine with and without aura. They have their own distinct clinical profiles. Unlike complicated migraine, headache in migraine with and without aura is a prominent and persistent symptom, lasting for over 72 h. Therefore, status migrainosus should not be classified as complicated migraine.

| 1 Migraine |

| 1.1 Migraine without aura |

| 1.2 Migraine with aura |

| 1.2.1 Migraine with typical aura |

| 1.2.1.1 Typical aura with headache |

| 1.2.1.2 Typical aura without headache |

| 1.2.2 Migraine with brainstem aura |

| 1.2.3 Hemiplegic migraine |

| 1.2.3.1 Familial hemiplegic migraine |

| 1.2.3.1.1 Familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 |

| 1.2.3.1.2 Familial hemiplegic migraine type 2 |

| 1.2.3.1.3 Familial hemiplegic migraine type 3 |

| 1.2.3.1.4 Familial hemiplegic migraine, other loci |

| 1.2.3.2 Sporadic hemiplegic migraine |

| 1.2.4 Retinal migraine |

| 1.3 Chronic migraine |

| 1.4 Complications of migraine |

| 1.4.1 Status migrainosus |

| 1.4.2 Persistent aura without infarction |

| 1.4.3 Migrainous infarction |

| 1.4.4 Migraine aura-triggered seizure |

| 1.5 Probable migraine |

| 1.5.1 Probable migraine without aura |

| 1.5.2 Probable migraine with aura |

| 1.6 Episodic syndromes that may be associated with migraine |

| 1.6.1 Recurrent gastrointestinal disturbance |

| 1.6.1.1 Cyclical vomiting syndrome |

| 1.6.1.2 Abdominal migraine |

| 1.6.2 Benign paroxysmal vertigo |

| 1.6.3 Benign paroxysmal torticollis |

The dissociation of IHS classification from commonly encountered conditions has continued with the 2013 beta version of the classification. Some commonly encountered conditions such as the migraine associated blackout or fainting, seizure like activity, chest pain, or vestibular symptoms as a manifestation of the migraine are conspicuously absent from the classification. Additionally, it is not unusual in children with migraine to present with isolated leg, body (corpalgia), or lower back pain, and nose bleed[5,6].

Although complicated migraine and migraine variants are used interchangeably. The question arises that how should migraine variants be classified? Based upon proposed common clinical profile, migraine variants remain as a subdivision of the complicated migraine. However, their subgrouping as migraine variants still remains clinically useful to indicate that these conditions have potential to develop in a full blown migraine in adult life.

It is important to realize that children with migraines may have episodes of a variety of isolated and independent self-limiting symptoms other than headache which may or may not coincide with migraine attack. Physicians should be aware of both the classification and the full clinical spectrum of the migraine.

Incidence of complicated migraine individually or collectively is unknown. Obviously, the incidence will also vary depending upon what is considered complicated migraine. However, in pediatric neurology they are the second most common condition after seizures requiring hospitalization. The frequency of the complicated migraine reported in select studies is shown in Table 2[7-9].

| Study type | Ref. | No. of patients | Frequency of the individual syndromes of complicated migraine reported |

| Retrospective | [7] | 111 | Migraine variants 24.3%, basilar type migraine 6.3%, benign paroxysmal vertigo (5.4%), hemiplegic migraine (3.6%), acute confusional migraine (2.7%), benign paroxysmal torticollis (2.7%), typical aura without headache (1.8%), abdominal migraine (1.8%), Alice in Wonderland syndrome (0.9%), ophthalmoplegic migraine (0.9%), and cyclical vomiting (0.9%) |

| Retrospective | [8] | 674 | Migraine variants 5.6%, abdominal migraine 39%, benign paroxysmal vertigo 38%, confusional migraine 13%, aura without migraine 9%, paroxysmal torticollis 5%, and a single child with cyclic vomiting |

| Retrospective, adults in Hyperacute Stroke Units | [9] | 375 | Conditions other than stroke 31%, which included 22% migraine, 14% functional neurological disorder, 12% syncope, and 6% seizure. In contrast to stroke patients, they tend to be younger, likely to have a brain MRI performed, and had a shorter length of hospital stay |

Pathophysiology of migraine has evolved over the last century through the vascular theory (1938), identification of intracranial pain-sensitive structures (1941), cortical spreading depression of Leão (1944), neurotransmitter (1959), spreading oligemia in migraine with aura (1981), neurogenic inflammation theory (1987), the discovery of sumatriptan (1988), calcitonin gene-related peptide (1990), the brainstem “migraine generator” (1995), migraine as a channelopathy and the genetic perspective (1996), and central sensitization and allodynia (1996)[10]. The exact mechanism of the central nervous system pathophysiologic dysfunction in migraine is unclear. It is generally accepted that spreading of neuronal depression, neurogenic inflammation, and the activation of trigeminovascular system are involved.

Migraine and epilepsy share a common pathophysiologic mechanism. Thus, it is not a surprise that both are quite similar in almost all aspects of their clinical manifestations and treatment strategies. Both events are triggered by an altered neocortical excitability. In migraine it is secondary to cortical spreading depression. The cortical spreading depression is a self-propagating wave of neuronal and glial depolarization that spreads across the cerebral cortex. The neocortical spreading provokes the expression of c-fos protein-like immunoreactivity within trigeminal nucleus caudalis via trigeminovascular mechanisms[11,12]. In contrast, the seizure is secondary to hypersynchronous neuronal activity[13]. This neurophysiologic difference, their relative speed of spread, are the basis for a clinical differentiation between migraine and seizure. Migraine evolves slowly and seizure onset is sudden and fast. Most ictal periods in seizure last less than 3 min while migraine episode evolves over and beyond 10 min[14].

This clinical distinction of onset and progression is lost when seizure lasts longer than 3 min like in complex partial seizure or when migraine becomes shorter as in complicated migraine. This can be explained partially based upon Piccinelli et al[15], who studied the clinical and neurophysiologic link between migraine and epilepsy. By studying 137 children with tension-type headache and migraine with and without aura, they concluded that there is a possible clinical continuum between migraine with aura and epileptic syndrome.

Variability in the presenting symptoms and context, both characterize migraine in contrast to the seizure. Acute confusional migraine is a rare migraine variant which manifests with a wide diversity of cortical dysfunctions such as speech difficulties, increased alertness, agitation, and amnesia. The exact pathophysiology remains unclear. However, the occipital cortical spreading depression may also extend to the temporal, parietal or frontal cortex causing transient hypoperfusion and dysfunction of the affected lobes[16].

It should be noted that clinical manifestations, sensory, psychosomatic, autonomic, and motor dysfunctions, are the same in both migraine and seizure. But sensory symptoms predominate in migraine while seizure is characterized by motor activity.

The reviews of the literature in regards to complicated migraine revealed a common clinical profile (Table 3).

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Presenting feature | Any neurologic sign or symptom other than headache |

| Age | Commonly, but not limited to, occurs during infancy and childhood |

| Sex | Boys dominate in migraine variants and girls dominate in the rest of the complicated migraine other than migraine variants |

| Onset | Acute or sudden but relatively slower than seizure |

| The context | Patients may have past episode of similar or different symptomatology suggesting migraine attack |

| Modifying factor | Unlike migraine, none |

| Family history | Unlike common migraine, in complicated migraine a family history of migraine is almost always present |

| Course | Transient, may occur once in lifetime or may become episodic but always reversible with the exception to alternating hemiplegia |

| Examination | With few exceptions, particularly between the episodes, neurologic examination is almost always normal |

| Differential diagnosis: common/rare | Partial seizures, seizure like activity, transient ischemic attack/migraine like syndrome1 and acute stroke |

| Investigation | Usually normal including neuroimaging and electroencephalography |

| Diagnosis | A short course of the presenting symptom between seizure and common migraine defines the complicated migraine |

Migraine variants are common during infancy and early childhood in males by Teixeira et al[8]. On the other hand, complicated migraines other than migraine variants are common in young females. Martens et al, studied 209 children presenting with headache and reported a mean age of 11.3 years, female 56.5%, unclassified headache: 23.4%; probable migraine 17.2%, migraine without aura 13.4%, complicated migraine 12.4%, migraine with aura 1.0%; tension-type 15.3%, and cluster headaches 0.5%, and secondary headaches 16.7%.

Because complicated migraines manifest as an acute cerebral dysfunction other than headache, considering the diagnosis of migraine as a subgroup may present hesitancy and its vividity and unfamiliarity provoke anxiety which results in an extensive work up[17].

In practice, most complicated migraine presents with the isolated sign or symptom. The isolated manifestation may occur independently, together, or in the midst of the migraine attack[18]. However, some may present with more than one neurologic or medical manifestation. Such patients should be screened for concomitant use of daily analgesic, contraceptive pill, and elevated body mass index. The headache is not a presenting symptom of complicated migraine. However, headaches often coexist with attack of complicated migraine.

Psychosomatic and autonomic presenting symptoms in migraines are commonly encountered but they are infrequently realized. These include palpitations, chest pain, depression, anxiety and panic disorders, and mood disorder. Young children may present with episodic behavioral problems such as being inattentive, poor impulse control, irritable, and/or socially withdrawn. Rarely, hypomania has been reported[19]. In such situations, commonly alternative diagnoses other than migraine or no diagnosis is made.

Onset of complicated migraines is acute but it is relatively slower than seizure. The time course of complicated migraine lies between seizure and migraine without aura. They may occur once in lifetime. However, a frequent self-limiting course is not unusual.

In making a clinical diagnosis, the context in which the patient’s problem is manifested is as important as the presenting symptom. Like presenting symptoms, the context is also variable in complicated migraine. Migraines are characterized by the variability of the symptoms. Additionally, the presence of migrainous symptoms in the background provide a clue for the diagnosis. If the context is not sought actively the clinical diagnosis of complicated migraine can be difficult.

Precipitating and relieving factors: Unlike common migraine, complicated migraine has no known provoking or relieving factors. However, like migraine complicated migraine resolves spontaneously.

At onset of complicated migraine, medical and neurologic examinations are normal. Medical examination may reveal lower than normal heart rate, hypotension, and facial pallor. With acute onset, occasionally eyelid swelling, joint pain without swelling, isolated dysarthria, incomplete or complete hemiparesis, or ocular motor deficit may be present.

Adherence to the presented clinical profile, normal neurologic examination, and the normal results of the select tests make the diagnosis of complicated migraine. The accuracy of clinical diagnosis can be increased substantially by a careful consideration of the presenting symptom, its course timeline, relationship with other symptoms, and actively seeking the etiology.

Conditions like acute confusional migraine, seizure like activity, and non-epileptic seizure as a manifestation of the migraine are likely to mimic seizure. Migraine precipitated seizure like activity usually occurs in the background of prolonged migrainous symptoms[20]. It is interesting to note that migraine does not only mimic but it can cause seizure, transient ischemic attack, or even stroke[21].

Differential diagnosis of complicated migraines in children includes partial seizures, transient ischemic attack, and migraine like syndromes.

A sequential history of the event and its clinical characteristics are essential in making the clinical diagnosis of epileptic seizure. The best indicators of a seizure are the rapid and self-limiting time-course, the post-event confusion, and if present, a puncture wound on the lateral border of tongue[22]. An abnormal EEG supports the diagnosis. However, a normal EEG does not exclude a clinical diagnosis of seizure.

Transient ischemic attack, although considered frequently, is a rare occurrence in a healthy child. However, this should be considered in children with blood and cardiac disorders.

A large body of literature supports an association between migraine with aura and ischemic stroke. This is observed particularly in women who use contraceptives and smoke cigarettes. Because the absolute risk of stroke is considerably low in patients with migraine, the vast majority of migraine patients will not experience a stroke event because of the migraine[23].

A presentation simulating migraine occurs in the patient with and without migraine. Migraine is precipitated by stress which may be external or internal[24]. Onset of a second condition, as in internal stress in migraine patient, is likely to trigger or change the previous migraine attack profile. This has been reported in infections[25,26] and in Sturge Weber syndrome[27]. The differential diagnosis of migraine like syndromes, their presenting symptoms, and the confirmatory laboratory tests are listed in Table 4.

| Migraine like syndrome | Presenting symptom | Confirmed by |

| Aseptic meningitis | Infants and children age < 5 yr presenting with constitutional symptoms together with meningeal signs | Cerebrospinal fluid study molecular testing by polymerase chain reaction[28] |

| Pseudotumor cerebri | Persistent headache with prominent visual symptoms and head tilt | An increased intracranial opening pressure measured in calm patient with straight leg position |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | Waxing and waning levels of consciousness, apnea, bradycardia before seizure | Brain computerized tomography and/or presence of blood or xanthochromic cerebrospinal fluid |

| Sinus venous thrombosis | Altered mentation with no obvious etiology or no seizures | Brain computerized tomography with and without contrast or MRV |

| Arteriovenous malformation | Sensory cutaneous aura with or without seizure or headache | MRA and MRV or computerized tomographic angiography |

| MELAS | Early symptoms, muscle weakness and pain, recurrent headaches, loss of appetite, vomiting, and seizures | MRI of the brain mimicking acute migrainous stroke but differs by having no respect to a specific cerebral arterial vascular territory |

| Brain tumor | Progressively worsening headache with onset of focal neurologic sign or seizure | Computerized tomography with contrast or MRI of the brain with and without contrast |

The clinical and neuroimaging profile of migraine like syndromes are rather unique and different from each other. It is also very different from complicated migraine. Like migraine without aura, headache is an initial and prominent symptom of migraine like syndromes except sinus venous thrombosis and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Their initial manifestation may be waxing and waning level of consciousness before developing loss of consciousness in sinus venous thrombosis and seizure in subarachnoid hemorrhage.

In the context of complicated migraine a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and thyroid function tests are justifiable. However, CSF study, EEG, and the neuroimaging study should be considered based on the clinical impression[28,29]. The results of the performed tests are almost always normal. They are performed primarily to exclude migraine like syndrome including bacterial or aseptic meningitis. In most cases of complicated migraine based on clinical assessment and the tests may not be indicated. But it plays a pivotal role in quelling the parental anxiety.

CSF abnormalities have been reported infrequently in patients with migraine. It is not clear whether or not all complicated migraine syndromes are associated with CSF abnormality. Normal CSF or CSF with both polymorphonuclear or lymphocytic pleocytosis[30,31], a raised intracranial pressure, an increased CSF sodium concentration[32], all are found during migraine with and without aura. Total protein content was significantly lower in migraine patients than the controls.

In the absence of any other detectable cause, the CSF changes were attributed to the effects of the migrainous process on meningeal vascular permeability[33]. Rossi et al studied four children with complicated migraine. On the basis of 23 previously reported cases along with their four cases, they concluded that pleocytosis is a secondary phenomenon.

In this respect, there are no common CSF characteristic which characterizes the complicated migraine. Select reports of biochemical changes distinguishing bacterial meningitis, aseptic meningitis, and migraine attack are shown in Table 5[34-39].

| Increased level in cerebrospinal fluid | Comments |

| Lactate | > 3.5 mmol/L is a good predictor of bacterial meningitis[34] |

| Procalcitonin | > 0.5 ng/mL is a good predictor of bacterial meningitis[35] |

| Ferritin | 106.39 +/- 86.96 ng/ dL (n = 24) was considerably higher than the viral meningitis group (10.17 +/- 14.09, P < 0.001)[36] |

| Cytokines | Children with mumps meningitis (n = 19), echovirus 30 meningitis (n = 22), with comparison to children without meningitis (n = 21)[37] |

| Glutamic acid | An excess of neuroexcitatory amino acids during migraine attacks supports a state of neuronal hyperexcitability[38] |

| 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid | Level was higher in migraine than the controls[39] |

The data on neuroimaging during an episode of complicated migraine is limited. Most data comes from the isolated or series of the reported cases. Indication to perform an MRI and MRA of the brain are migraine with aura, hemiplegic migraine, or when an alternative diagnosis such as migraine like syndrome is being considered.

In general, conventional neuroimaging in complicated migraine is normal or likely to reveal incidental findings. Martens et al[40] retrospectively evaluated the role of cerebral MRI and EEG in 209 children presenting with headache. The study revealed signs of sinus disease (7.2%), pineal cysts (2.4%), arachnoidial cyst (1.9%) and Chiari malformation (1.9%), unspecified signal enhancement (1.0%) and pituitary enlargement, inflammatory lesion, angioma, cerebral ischemia, and intra-cerebral cyst, each 0.5%[40]. Such a spectrum of neuroradiologic findings is likely to unveil during the assessment of headache, seizure, developmental delay, or during an investigation of an acute brain insult. Common sources for these incidental findings on brain MRI might relate to a delayed developmental status rather than other neurologic diagnoses[41]. Nonetheless, MRI of the brain should be performed in a situation when clinical diagnosis of complicated migraine is uncertain or when the parents are concerned. This will provide acceptance of the diagnosis and treatment. Routinely performed brain CT in Emergency Department, unless an intracranial hemorrhage is suspected, is not a cost effective way of entertaining the diagnosis of complicated migraine.

The use of newer MRI sequences in the evaluation of complicated migraine has revealed pathophysiology. The select multimodality neuroimaging and their results are provided in Table 6[42-45].

| Neuroimaging type and the clinical conditions | Study revealed |

| Multimodality neuroimaging in a single familial hemiplegic migraine[42] | Cytotoxic edema along with evidence of hypometabolism but no evidence of hypoperfusion of the affected cerebral hemisphere |

| Perfusion- and susceptibility-weighted imaging in a 13-year-old-female 3 h after the right hemiplegia[43] | Hypoperfusion in the left cerebral hemisphere and a matching prominent hypotensity, respectively. Diffusion tensor imaging sequences were normal. These abnormalities completely resolved 24 h after the attack onset |

| Perfusion- and diffusion-weighted MRI during visual auras in four migraineurs[44] | Cerebral blood flow and volume, both decreased by 16%-53% and 6%-33%, respectively. Mean transit time in the affected occipital cortex was increased by 10%-54%. No changes in the diffusion coefficient were observed during and after the resolution of the visual aura |

| Brain MRI in six population and 13 clinic-based meta-analysis studies in migraines with and without aura[45] | White matter abnormalities, silent infarct-like lesions, and volumetric changes in both gray and white matter regions were more common in migraineurs than in control groups. These data suggest that migraine may be a risk factor for structural changes in the brain |

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is another non-invasive tool to investigate the central nervous system abnormality. There is compelling evidence that cortical excitability is modified in migraine patients even between attacks[46].

Rarely occurring migrainous infarction mostly occurs in the posterior cerebral circulation in younger women with migraine with aura. Acute ischemic lesions are often multiple and located in distinct arterial territories[47].

In complicated migraine, the role of neurophysiologic studies, EEG, and visual evoked potential (VEP) are very limited. But it has increased our understanding regarding the physiologic dysfunction of the spectrum of migraine.

An EEG is not recommended in the management of headache or migraine. Data on the role of EEG in diagnosis of complicated migraines is limited. However, it plays a supportive role when performed in the context of seizure or seizure like activity precipitated by migraine and when a non epileptic seizure is being considered.

Nejad Biglari et al[48] study revealed EEG abnormality in 20% of patients with migraine. Distribution of the migraine type included migraine without aura 63%, migraine with aura 23%, migraine variant 8%, and epileptic syndromes 5%. Comparing the EEG abnormalities with the type of migraine revealed a significant association with migraine with aura (P = 0.03).

Manifestation of visual symptoms together with postictal headache during occipital seizure can be mistaken for migraine with visual aura. In such situations, the EEG monitoring is crucial for reaching the correct diagnosis[49].

Visual Evoked Potential (VEP) findings in migraine support the theory of neuronal sensory excitability of the occipital cortices. The central nervous dysfunction specific to migraine can be detected during headache and headache free period. The evoked potential amplitude is a quantitative index of the neuronal population activated by certain sensory inputs. It tends to decrease progressively as a normal response during repetitive sensory stimulation which is known as habituation. The habituation occurs to a lesser degree when brain is more excitable or central nervous systems that regulate habituation are less active.

A reduced habituation of visual evoked potential has been reported. Spreafico et al[50] studied VEPs in 53 migraineurs, 21 with preventive therapy and 32 with no preventive therapy, and 20 healthy controls. In comparison to healthy controls, P100 latencies in no therapy group were lower and in therapy group were same. They speculated that the different responsiveness of the visual system in migraineurs is probably due to a dysmodulation of sensor input leading to facilitation of visual processing.

Bjørk et al[51], recorded steady state visual evoked potential and EEG-responses for specific flash stimuli from 33 migraineurs without aura, 8 migraineurs with aura, and 32 healthy controls. Before attack, driving power of 12 Hz. was increased. Attacks trigger light sensitivity, photophobia, and pain intensity. Between attacks, driving responses to 18 Hz. and 24 Hz. were attenuated in migraineurs without aura. They concluded that abnormal photic driving may be related to the pathophysiology of clinical sensory hypersensitivity.

It is important to decide how far one should investigate? Continued investigation without a clinical explanation, when the results of the tests are normal, may further enhance an already anxious parent. In fact, it may delay the diagnosis of complicated migraine. Viticchi et al[52], analyzed 400 consecutive patients with migraine without aura to evaluate whether EEG performance negatively influences the time necessary in obtaining a correct diagnosis. Delay was defined as a time to diagnosis greater than 1-year. It was associated with a significant risk of diagnostic delay (OR = 1.66, 95%CI: 1.65-1.66, P < 0.001) EEG represented the most often (20%) performed non-radiologic examination.

No clinical treatment trials are available in children with complicated migraine. Thus, the treatment is based on empirical data, often extrapolated from adults, and most importantly from the personal experience of the treating physician. In the case of complicated migraine, once the diagnosis is made the treatment strategy is similar to migraine with disability or when the patient’s daily routine is interrupted.

In Emergency Department, the primary goal for evaluation of the children with complicated migraine is to identify those who have a treatable condition or a disorder associated with high morbidity or mortality (Table 4). The initial management should focus on vital signs and signs of increased intracranial pressure[53], and on providing the symptomatic and supportive treatments.

Symptomatic or supportive care is the backbone of the clinical management. Its prompt implementation even in lack of a definitive diagnosis leads to the best possible outcome. Urgent medical interventions include hydration with intravenous fluid and symptomatic treatment for the associated symptoms. Symptomatic treatments for nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and headache should be administered selectively. This is all that is needed in most patients with complicated migraine. A sleeping aid which is the best known conservative abortive therapy for migraine should be considered[54,55].

Richer et al[56] from their randomized controlled trial of treatment expectation and intravenous fluid in the Emergency Department, concluded that intravenous fluid hydration has a clinically meaningful response in 17.8% children with migraine. The overall decrease in pain was insignificant at 30 min. Recurrence of headache was common in 33% children after the Emergency Department discharge.

In Pediatric Emergency Department when the combination of standard intravenous therapy (n = 87) was compared with non-standardized therapy (n = 165), the standardized combination therapy was effective in reducing head pain scores (decrease of 5.3 vs 6.9, P < 0.001), length of emergency department stay (5.3 vs 4.4 h, P = 0.008), and hospital admission rates (32% vs 3%, P < 0.001). The standardized therapy included a normal saline fluid bolus, ketorolac, prochlorperazine, and diphenhydramine. Metoclopramide was occasionally substituted during prochlorperazine shortages[56].

In the presence of nausea, vomiting, and a reduced gastric emptying known to occur during migraine attack[57,58], medications should be administered intravenously. This intervention is particularly important if the overuse of oral analgesics is suspected.

Due to the transient self-limiting nature of complicated migraine, abortive therapy with triptan is usually not needed in complicated migraine. However, the triptan is useful in those patients who have infrequent attacks with disability. Due to vasoconstrictive side effect triptans are contraindicated in patients with hemiplegic migraine. In such a situation, the use of verapamil antimigrainous preventing future attacks is recommended[59].

If admitted, inpatient management goal is to reaffirm the initial diagnosis and to identify those children who will need a daily drug prophylaxis. What will be the best drug in a particular patient with complicated migraine? Author’s (SG) personal preference is to provide assurance, institute a regular lifestyle, and initiate an antimigrainous therapy, if needed. These elements also alleviate the future need for triptan use.

Assurance to the parents in an acute setting is a basic and an essential part for calming down the parental anxiety. It encourages their active participation and increases parental acceptance for the drug’s compliance. Assurance begins with the very first encounter long before making the diagnosis. Based upon an existing problem and a potential unfolding new complication, the clinical diagnosis should be presented with confidence. An upfront plan for realistic expectations and a timely intervention should be discussed.

Rarely, new onset vivid or prolonged symptom such as hemiparesis, vision loss, or seizure like activity as a manifestation of the migraine may demand the initiation of a preventive therapy[60]. However, if the symptoms become episodic or child has missed school days secondary to migraine, a daily antimigrainous drug therapy to prevent future attacks is indicated.

Before starting antimigrainous drug therapy, it is equally important if not more important to instruct the patient to simultaneously institute three elements, to sleep on time, eat on time, and take analgesic at the first onset of a migraine symptom. It is important to realize that it is not the type or dosage of an analgesic rather it is the timing when analgesic is taken that is an effective intervention. The first two have a preventive role like the preventive drug in decreasing the frequency and severity of the migraines. The analgesic use lessens the severity of the ongoing episode. The regular lifestyle and analgesic use are not a substitute rather they have a complementary role in providing an optimum antimigrainous benefit in majority of children with migraine with disability.

Many preventive agents are safe but none are currently FDA-approved for children. Controlled clinical trials investigating the use of both abortive and preventive medications have high placebo response rates. Furthermore, the shorter duration of headaches and other unusual features seen in children make designing of randomized controlled trials problematic. As a result the majority of children who present to doctor’s office with migraine’s disability do not receive prophylactic therapy. As such due to lack of evidence-based guidelines the antimigrainous prophylactic therapy practices vary widely even among pediatric neurologists[61].

The goal of antimigrainous prophylactic drug therapy is to prevent future migraine attack rather than merely headache. This requires a comprehensive approach and prophylactic therapy works best in conjunction with above described three elements of conservative therapy. In lack of their reenforcement the drug therapy alone is likely to have less than optimum results.

Amongst a large number and different classes of medication, cyproheptadine (antihistaminic), propranolol (beta blocker), topiramate (antiepileptic), amitriptyline (antidepressant), and verapamil (calcium channel blocker) are a short list of drugs to manage the majority of the children with migraine. Which drug should be used in a particular patient? That should be selected based on the presence of the second common symptom which is bothersome for the patient.

Drug’s side effect should be taken advantage of in the management. For example, for an associated poor appetite in young children cyproheptadine; for an increased sympathetic symptom in young adult such as anxiety, irritability, tremor, or palpitation, propranolol; and in the presence of an increased body mass index, migraine precipitated seizure, or pseudotumor cerebri, topiramate should be considered. The physician should familiarize themselves with at least three drugs and their dosages, cyproheptadine, proponolol, and topiramate. The parental concern of side effects can be minimized by starting a small dose of the selected drug and setting an individualized preventive goal for the drug therapy.

In the absence of any other identifiable etiology children with complicated migraine have a full clinical recovery. With an exception of a rarely occurring alternating hemiplegia, complicated migraines are non-progressive. However, the migraine variants are likely to evolve to a full blown migraine in adult life.

The long-term course of migraine with aura has been explored. A study of an 11-year follow-up natural history of 77 children with migraine with aura revealed 23.4% headache-free, 44.1% still had migraine with aura. And 32.5% children with migraine with aura transformed to other types of headache. Children with basilar type migraine showed the highest (38.5%) headache remission rate. The remission of aura occurred in 54.1% of the children. A lower rate of remission occurred in those with visual, sensory, or aphasic aura[62].

MEDICOLEGAL IMPLICATION

Multiple clinical situations in complicated migraine may lead to the medical legal issues. The physician is likely to be implicated in a delay in making or making an incorrect diagnosis. A wide spectrum and the fragmented presentation in time and space may result in medicolegal issues. Unawareness of these syndromes may be anxiety provoking leading to extensive investigations causing delay in a clinically based diagnosis. On the other hand, a casual diagnosis may fall too short in making a correct diagnosis. To add to the perplexity, CSF examination may reveal pleocytosis. The presence of fever, vomiting, or other constitutional symptoms early in the course of the illness should direct physician to a correct diagnosis[63].

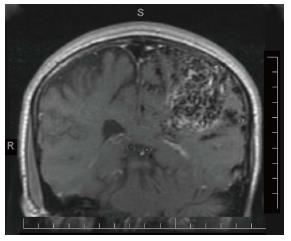

Children with migraine at onset of a new condition, such as acute infection, arteriovenous malformation, or brain tumor, may simulate like the previous migraine attack profile. They are likely to present with a mixed symptomatology of migraine and of the second condition. In such a situation, the diagnosis of a new condition is easily overlooked. This can be prevented by a differential thinking regarding both conditions. An MRI of the brain of a 15-year-old male with previous diagnosis of migraine with aura revealed the left parietal arteriovenous malformation (Figure 1). This was suspected based upon a history of slowly evolving prolonged right hemisensory cutaneous aura.

Medicolegal implication can be avoided by closely following the described common clinical profiles for the complicated migraine, migraine without aura, and being attentive to the clinical characteristics of the migraine like syndromes (Table 4). The clinicians should get acquainted with a fragmented presentation of migraines in avoidance of the medicolegal implications.

Progressively increasing health cost demands a direct critical and differential thinking of the presenting symptoms in the diagnosis of complicated migraine.

What is the status of migraine variant in the IHS classification? How to express collectively about two dozens of conditions with a common clinical profile, and how to distinguish complicated migraine from complication of migraine? The future classification system should clarify these questions.

The neurophysiologic studies with evoked potential and functional neuroimaging are likely to play an important role in future understanding of pathophysiology and to explore the novel therapeutic strategies for complicated migraine. Metabolic changes of the cortex and subcortical structures in complicated migraine should be assessed by transcranial magnetic stimulation or near-infrared spectroscopy[64].

This is the first report of a common profile in aid to the clinical diagnosis of complicated migraine. Both groups of children, well-described or not yet described individual syndromes of complicated migraine, can be diagnosed clinically by their common clinical profile; an acute onset and a relatively short and self-limiting course of the neurologic manifestations other than headache of unidentifiable etiology.

Complicated migraine does not only mimic conditions like seizure, non-epileptic event, transient ischemic attack, or stroke but it can also cause them. At times, normal results incite further anxiety and thus, more testing and as a result delay in diagnosis. For these reasons, the clinicians should be aware of this very much concerning the common neurological conditions presenting in the Emergency Department.

Adherence to the proposed common clinical profile will improve the accuracy of clinical diagnosis. It will optimize the use of laboratory tests. Once the complicated migraine is considered, they do not impose a diagnostic difficulty. This systematic approach in a timely manner is essential in avoidance of a medicolegal implication. In addition, we provided a common preventive treatment strategy for the treatment of the migraines.

Future classification should minimize the separation of the clinically encountered syndromes and should coin a single word to address collectively this subtype of acute migraine with a common clinical profile. Future clinical review should evaluate the applicability of the proposed clinical profile in making the diagnosis of the individual syndromes of complicated migraine.

The authors acknowledge our sincere thanks to Aziez Ahmed, MD and Susan R Medalie, OMS-IV for their critical review of this manuscript.

| 1. | Hargreaves RJ, Shepheard SL. Pathophysiology of migraine--new insights. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999;26 Suppl 3:S12-S19. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Silberstein SD. Advances in understanding the pathophysiology of headache. Neurology. 1992;42 Suppl 2:6-10. |

| 3. | Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia. 1988;8 Suppl 7:1-96. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd ed (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5134] [Cited by in RCA: 5559] [Article Influence: 463.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kakisaka Y, Ohara T, Katayama S, Suzuki T, Hino-Fukuyo N, Uematsu M, Kure S. Lower back pain as a symptom of migrainous corpalgia. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:676-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Durán-Ferreras E, Viguera J, Patrignani G, Martínez-Parra C. Epistaxis accompanying migraine attacks. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:958-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pacheva IH, Ivanov IS. Migraine variants--occurrence in pediatric neurology practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:1775-1783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Teixeira KC, Montenegro MA, Guerreiro MM. Migraine equivalents in childhood. J Child Neurol. 2014;29:1366-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Reid JM, Currie Y, Baird T. Non-stroke admissions to a hyperacute stroke unit. Scott Med J. 2012;57:209-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tfelt-Hansen PC, Koehler PJ. One hundred years of migraine research: major clinical and scientific observations from 1910 to 2010. Headache. 2011;51:752-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baimaj V. Chromosomal polymorphisms of constitutive heterochromatin and inversions in Drosophila. Genetics. 1977;85:85-93. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Qiu J, Matsuoka N, Bolay H, Bermpohl D, Jin H, Wang X, Rosenberg GA, Lo EH, Moskowitz MA. Cortical spreading depression activates and upregulates MMP-9. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1447-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ayata C. Cortical spreading depression triggers migraine attack: pro. Headache. 2010;50:725-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rogawski MA. Common pathophysiologic mechanisms in migraine and epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:709-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Piccinelli P, Borgatti R, Nicoli F, Calcagno P, Bassi MT, Quadrelli M, Rossi G, Lanzi G, Balottin U. Relationship between migraine and epilepsy in pediatric age. Headache. 2006;46:413-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schipper S, Riederer F, Sándor PS, Gantenbein AR. Acute confusional migraine: our knowledge to date. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12:307-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Naeije G, Gaspard N, Legros B, Mavroudakis N, Pandolfo M. Transient CNS deficits and migrainous auras in individuals without a history of headache. Headache. 2014;54:493-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pacheva I, Ivanov I. Acute confusional migraine: is it a distinct form of migraine? Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:250-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Datta SS, Kumar S. Hypomania as an aura in migraine. Neurol India. 2006;54:205-206. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Verrotti A, Coppola G, Di Fonzo A, Tozzi E, Spalice A, Aloisi P, Bruschi R, Iannetti P, Villa MP, Parisi P. Should “migralepsy” be considered an obsolete concept? A multicenter retrospective clinical/EEG study and review of the literature. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;21:52-59. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Laurell K, Lundström E. Migrainous infarction: aspects on risk factors and therapy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gupta SN, Gupta VS. Bilateral Tongue Bite during Epileptic Seizure: Nomenclature and Mechanism. Austin J Neurol Disord Epilepsy. 2014;1:2. |

| 23. | Kurth T. The association of migraine with ischemic stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Noseda R, Kainz V, Borsook D, Burstein R. Neurochemical pathways that converge on thalamic trigeminovascular neurons: potential substrate for modulation of migraine by sleep, food intake, stress and anxiety. PLoS One. 2014;9:103929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Verma R, Lalla R. Increased frequency of headache and change in visual aura due to occipital cysticercus granuloma. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012006919. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Sartor H, Thoden U. [Migraine with aura as early symptom of neurosyphilis]. Schmerz. 1999;13:48-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nomura S, Shimakawa S, Fukui M, Tanabe T, Tamai H. Lamotrigine for intractable migraine-like headaches in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Brain Dev. 2014;36:399-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dawood N, Desjobert E, Lumley J, Webster D, Jacobs M. Confirmed viral meningitis with normal CSF findings. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014203733. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Pavone P, Conti I, Le Pira A, Pavone L, Verrotti A, Ruggieri M. Primary headache: role of investigations in a cohort of young children and adolescents. Pediatr Int. 2011;53:964-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Negrini B, Kelleher KJ, Wald ER. Cerebrospinal fluid findings in aseptic versus bacterial meningitis. Pediatrics. 2000;105:316-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1103-1108. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Harrington MG, Fonteh AN, Cowan RP, Perrine K, Pogoda JM, Biringer RG, Hühmer AF. Cerebrospinal fluid sodium increases in migraine. Headache. 2006;46:1128-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Day TJ, Knezevic W. Cerebrospinal-fluid abnormalities associated with migraine. Med J Aust. 1984;141:459-461. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Mekitarian Filho E, Horita SM, Gilio AE, Nigrovic LE. Cerebrospinal fluid lactate level as a diagnostic biomarker for bacterial meningitis in children. Int J Emerg Med. 2014;7:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Konstantinidis T, Cassimos D, Gioka T, Tsigalou C, Parasidis T, Alexandropoulou I, Nikolaidis C, Kampouromiti G, Constantinidis T, Chatzimichael A. Can Procalcitonin in Cerebrospinal Fluid be a Diagnostic Tool for Meningitis? J Clin Lab Anal. 2014;May 5; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Rezaei M, Mamishi S, Mahmoudi S, Pourakbari B, Khotaei G, Daneshjou K, Hashemi N. Cerebrospinal fluid ferritin in children with viral and bacterial meningitis. Br J Biomed Sci. 2013;70:101-103. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Sulik A, Kroten A, Wojtkowska M, Oldak E. Increased levels of cytokines in cerebrospinal fluid of children with aseptic meningitis caused by mumps virus and echovirus. Scand J Immunol. 2014;79:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Martínez F, Castillo J, Rodríguez JR, Leira R, Noya M. Neuroexcitatory amino acid levels in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid during migraine attacks. Cephalalgia. 1993;13:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kovács K, Bors L, Tóthfalusi L, Jelencsik I, Bozsik G, Kerényi L, Komoly S. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) investigations in migraine. Cephalalgia. 1989;9:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Martens D, Oster I, Gottschlling S, Papanagiotou P, Ziegler K, Eymann R, Ong MF, Gortner L, Meyer S. Cerebral MRI and EEG studies in the initial management of pediatric headaches. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13625. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Gupta S, Kanamalla U, Gupta V. Are incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance images in children merely incidental? J Child Neurol. 2010;25:1511-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kumar G, Topper L, Maytal J. Familial hemiplegic migraine with prolonged aura and multimodality imaging: a case report. Headache. 2009;49:139-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Bosemani T, Burton VJ, Felling RJ, Leigh R, Oakley C, Poretti A, Huisman TA. Pediatric hemiplegic migraine: role of multiple MRI techniques in evaluation of reversible hypoperfusion. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:311-315. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Cutrer FM, Sorensen AG, Weisskoff RM, Ostergaard L, Sanchez del Rio M, Lee EJ, Rosen BR, Moskowitz MA. Perfusion-weighted imaging defects during spontaneous migrainous aura. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Bashir A, Lipton RB, Ashina S, Ashina M. Migraine and structural changes in the brain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2013;81:1260-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Fumal A, Bohotin V, Vandenheede M, Schoenen J. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in migraine: a review of facts and controversies. Acta Neurol Belg. 2003;103:144-154. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Wolf ME, Szabo K, Griebe M, Förster A, Gass A, Hennerici MG, Kern R. Clinical and MRI characteristics of acute migrainous infarction. Neurology. 2011;76:1911-1917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Nejad Biglari H, Rezayi A, Nejad Biglari H, Alizadeh M, Ahmadabadi F. Relationship between migraine and abnormal EEG findings in children. Iran J Child Neurol. 2012;6:21-24. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Italiano D, Grugno R, Calabrò RS, Bramanti P, Di Maria F, Ferlazzo E. Recurrent occipital seizures misdiagnosed as status migrainosus. Epileptic Disord. 2011;13:197-201. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Spreafico C, Frigerio R, Santoro P, Ferrarese C, Agostoni E. Visual evoked potentials in migraine. Neurol Sci. 2004;25 Suppl 3:S288-S290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Bjørk M, Hagen K, Stovner Lj, Sand T. Photic EEG-driving responses related to ictal phases and trigger sensitivity in migraine: a longitudinal, controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:444-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Viticchi G, Falsetti L, Silvestrini M, Luzzi S, Provinciali L, Bartolini M. The real usefulness and indication for migraine diagnosis of neurophysiologic evaluation. Neurol Sci. 2012;33 Suppl 1:S161-S163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Nallasamy K, Singhi SC, Singhi P. Approach to headache in emergency department. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:376-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Guidetti V, Dosi C, Bruni O. The relationship between sleep and headache in children: implications for treatment. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:767-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Singh NN, Sahota P. Sleep-related headache and its management. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2013;15:704-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Richer L, Craig W, Rowe B. Randomized controlled trial of treatment expectation and intravenous fluid in pediatric migraine. Headache. 2014;54:1496-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Leung S, Bulloch B, Young C, Yonker M, Hostetler M. Effectiveness of standardized combination therapy for migraine treatment in the pediatric emergency department. Headache. 2013;53:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Yalcin H, Okuyucu EE, Ucar E, Duman T, Yilmazer S. Changes in liquid emptying in migraine patients: diagnosed with liquid phase gastric emptying scintigraphy. Intern Med J. 2012;42:455-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Chu ER, Lee AW, Chen CS. Resolution of visual field constriction with verapamil in a patient with bilateral optic neuropathy, migraine and Raynaud‘s phenomenon. Intern Med J. 2009;39:851-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Pelzer N, Stam AH, Haan J, Ferrari MD, Terwindt GM. Familial and sporadic hemiplegic migraine: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2013;15:13-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Kacperski J, Hershey AD. Preventive drugs in childhood and adolescent migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18:422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Termine C, Ferri M, Livetti G, Beghi E, Salini S, Mongelli A, Blangiardo R, Luoni C, Lanzi G, Balottin U. Migraine with aura with onset in childhood and adolescence: long-term natural history and prognostic factors. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:674-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Rossi LN, Vassella F, Bajc O, Tönz O, Lütschg J, Mumenthaler M. Benign migraine-like syndrome with CSF pleocytosis in children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1985;27:192-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Obrig H. NIRS in clinical neurology - a ‘promising’ tool? Neuroimage. 2014;85 Pt 1:535-546. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer: Al-Haggar M, Classen CF, Romano C S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/