Published online Nov 8, 2014. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v3.i4.69

Revised: September 2, 2014

Accepted: October 23, 2014

Published online: November 8, 2014

Processing time: 152 Days and 2.7 Hours

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is the most common glomerular disease of childhood. Steroid-dependent and steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome present challenges in their pharmaceutical management; patients may need several immunosuppressive medication for optimum control, each of which medication has its own safety profile. Rituximab (RTX) is a monoclonal antibody that targets B cells and has been used successfully for management of lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis. Recent clinical studies showed that rituximab may be an efficacious and safe alternative for the treatment of complicated nephrotic syndrome. In this review article, we aim to review the efficacy and safety of RTX therapy in nephrotic syndrome. We reviewed the literature pertaining to this topic by searching for relevant studies on PubMed and Medline using specific keywords. The initial search yielded 452 articles. These articles were then examined to ensure their relevance to the topic of research. We focused on multicenter randomized controlled trials with relatively large numbers of patients. A total of 29 articles were finally identified and will be summarized in this review. The majority of clinical studies of RTX in complicated pediatric NS showed that rituximab is effective in approximately 80% of patients with steroid-dependent NS, as it decreases the number of relapses and steroid dosage. However, RTX is less effective at achieving remission in steroid-resistant NS. RTX use was generally safe, and most side effects were transient and infusion-related. More randomized, double-blinded clinical studies are needed to assess the role of RTX in children with nephrotic syndrome.

Core tip: Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is the most common pediatric glomerular disease. Although outcomes are favorable, the treatment of complicated nephrotic syndrome can be challenging. Rituximab (RTX) offers a safe and effective alternative to current immunosuppressive therapies for complicated cases of NS. The best outcomes are seen in patients with steroid-dependent NS who have failed to respond to multiple therapies. However, the benefits of RTX therapy are limited in patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Successful RTX therapy induces prolonged remission and enables discontinuation of other medications without increasing the risk of infection and other adverse events.

- Citation: Safdar OY, Aboualhameael A, Kari JA. Rituximab for troublesome cases of childhood nephrotic syndrome. World J Clin Pediatr 2014; 3(4): 69-75

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v3/i4/69.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v3.i4.69

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is the most common glomerular disease of childhood. Although long-term outcomes are favorable, a significant proportion of patients develops steroid-dependent disease or frequent relapses and is at high risk for prolonged steroid exposure. Such patients develop steroid toxicity, including hypertension and growth arrest[1]. Approximately 10%-20% of patients with nephrotic syndrome do not respond to steroid therapy (steroid-resistant disease); such patients are at a significant risk of developing end-stage renal failure[2]. Currently used second line agents for the long-term treatment of patients with complicated nephrotic syndrome, such as calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), levamisole and others, suppress or control proteinuria. However, these immunosuppressive agents have their own adverse systemic effects, including nephrotoxicity with CNI; Gastrointestinal upset with MMF, and leukopenia with levamisole. No high-quality randomized controlled trials have performed head-to-head comparisons to establish the superior efficacy or safety of one immunosuppressive agent over its counterparts. None of these agents “cure” the disorder, and their exact mechanism of action in nephrotic syndrome is still largely unknown. Most patients experience a recurrence of proteinuria or nephrotic syndrome after medications are discontinued.

Rituximab (RTX) is a chimeric, monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody that targets B lymphocytes and causes Fc-mediated cell lysis[3,4]. It has been increasingly used in recent years to treat various immunological and non-immunological diseases. Over the last 7 years, a number of groups have shown that the depletion of CD20-positive B lymphocytes with the use of the chimeric monoclonal antibody RTX can lead to long-lasting remission of nephrotic syndrome due to minimal change disease (MCD) or focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)[5-8].

Many years ago, Shalhoub et al[9] proposed that T-cells are the main culprit in the pathogenesis of nephrotic syndrome. However, past evidence has shown that CD23 (a B-cell marker), is elevated during clinical relapse in steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome[10]. It is well known that B-cells play multiple physiological roles in immune system function. These cells are the precursors of antibody-producing cells (i.e., plasma cells). They also serve as antigen-presenting cells and are vital to cytokine production and secretion of the co-stimulatory signals that are required for CD4 activation.

Treatment with RTX does not appear to cure nephrotic syndrome. Patients often relapse several months following treatment with RTX (Table 1).

| Ref. | Demographics | Histologic findings | No. of doses | Outcome |

| Gulati et al[7] | SDNS Age (mean): 12.7 ± 9.1 yr 33 SRNS M: 17 F: 16 Age (mean): 11.7 ± 2.9 yr M: 19 F: 5 | SRNS 17 MCD (51%) 16 FSGS (49%) SDNS 12 MCD (50%) 2 FSGS (8%) 2 Mesangial hypercelluarity (8%) 8 No biopsy (33%) | SDNS 2 doses SRNS 4 doses | SDNS: 1 yr 20 remission; after 1 yr, 17 still in remission SRNS at 9 mo: 9 CP, 7 PR, 17 NON After 1 yr: 7 CR, 8 PR |

| Kemper et al[8] | 37 SDNS M: 25 F: 12 Age (mean): 4.4 ± 3.1 yr | 1-4 doses | After 1 yr, 26 patients (70.3%) remained in remission After 2 yr, 12 patients (41%) remained in remission | |

| Guignonis et al[5] | 22 SDNS Age: 6.3-22 yr | Immunosuppressive withdrawn in 19 patients with no relapse of proteinuria (85%) | ||

| Iijima et al[11] | 48 SRNS RTX 24 (intervention) Placebo 24 (control) | 4 infusions weekly for 4 doses | ||

| Tellier et al[12] | 18 SDNS M: 9 F: 9 Age (median): 2.8 yr (1.6-7.4) | One to four infusions | 22% had remission without relapse and increased duration of remission | |

| Kimata et al[17] | 5 SDNS Age (median): 6.3 yr (0.9-8.4) | Four doses every 3 mo | Number of relapses = 0 after the last dose of RTX | |

| Ravani et al[13] | 46 PT SDNS Age (mean): 9.9 ± 4.3 yr M: 29 F:17 | One to five | Probability of remission after rituximab At 6 mo: 48% At 1 yr: 20% At 2 yr: 10% | |

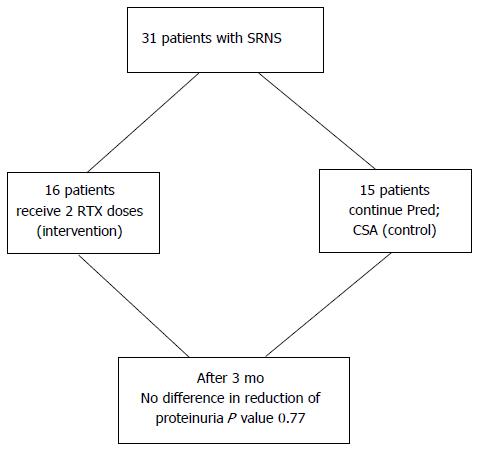

| Magnasco et al[20] | SRNS 31 Median: 7.9 ± 4.1 yr M: 19 F: 12 Control group: 15 Intervention: 16 | 19 FSGS (61%) 7 MCD (23%) 5 no biopsy (16%) | No change in proteinuria | |

| Prytula et al[16] | SDNS/FR 28 Age (median): 4 yr (18 mo -17 yr) M: 25 F: 3 SRNS 27 Age (median): 3 yr (18 mo-11 yr) M: 17 F: 10 | SDNS MCD 17 FSGS 5 Mesangial proliferation 2 IgM nephropathy 1 No biopsy 3 SRNS 11 MCD 11 FSGS Mesangial proliferation 3 IgM nephropathy 1 No Biopsy 1 | SDNS CR: 17 (61%) PR: 8 (28% NR: 3 (11%) SRNS CR 6 (22%) PR 12 (44%) NR 9 (34%) |

This review article provides insight regarding the efficacy of RTX in steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome and examines adverse events related to the use of RTX in patients with nephrotic syndrome.

For a better understanding of this review, it is prudent to clarify the definitions of a few key terms prior to delving into more detail regarding the core topic. Steroid dependent-nephrotic syndrome (SDNS) has been defined according to the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Pädiatrische Nephrologie standard definition as at least two relapses with alternate-day prednisone treatment (40 mg/m2) or within 14 d after stopping this treatment. Frequent relapsing nephrotic syndrome has been defined as 2 or more relapses within 6 mo and/or 4 or more relapses within 12 mo. Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome has been defined as a lack of remission (urine albumin nil/trace by dipstick for 3 consecutive days) despite therapy with prednisone at 2 mg/kg per day for 4 wk.

We searched medical databases including PubMed and Medline to identify studies that addressed the efficacy and safety of RTX in children. The search words were “Nephrotic syndrome”, “Steroid dependent”, “Steroid resistant”, “Children”, “Rituximab and adverse effect” and “RTX”. We included randomized clinical trials and case series. The full texts of all potentially relevant abstracts were retrieved for further review.

The literature review showed that past evidence favors the use of RTX as a promising agent for maintaining remission in SDNS. RTX seems to be effective in terms of reducing relapses and reducing the required steroid dose.

In a recent multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial, Iijima et al[11] showed that RTX is effective and safe in children with SDNS and frequent relapsing nephrotic syndrome. A total of 48 patients were enrolled (24 received RTX, and 24 received placebo). Patients receiving RTX had a longer median relapse-free period compared to placebo (267 d vs 101 d; P value < 0.0008). Ten patients (42%) treated with RTX developed at least one serious adverse event, compared to 6 patients in the placebo group (25%); this difference was not statistically significant, with a P value of > 0.36 (Table 1).

Guigonis et al[5] demonstrated the efficacy of RTX in maintaining prolonged and effective remission in 22 children with steroid- or cyclosporine-dependent nephrotic syndrome. One or more immunosuppressive treatments could be withdrawn in 19 of these 22 patients (85%), with no relapse of proteinuria and without increasing the doses of other immunosuppressive drugs (Table 1).

Gulati et al[7] reported the efficacy and safety of RTX in SDNS refractory to standard therapy in a 3-year long prospective cohort study that was conducted in tertiary care centers in India and the United States. After steroid-induced remission, RTX was given at a mean dose of 400 ± 20.7 mg/wk for 2 wk. After 12 mo, remission was sustained in 20 (83.3%) patients. The mean number of relapses before therapy decreased significantly (P = 0.001). At a mean follow-up of 16.8 ± 5.9 mo (range, 12 to 38 mo), remission was sustained in 17 (71%) patients (Table 1).

Kemper et al[8], in a study of RTX in 37 children with steroid-dependent disease, showed that 26 patients (70.6%) remained in remission after 12 mo of treatment. In 29 children with prolonged follow up (for > 2 years), 12 children maintained remission (41%). By giving additional 2-4 courses to 19 patients, the number of patients who maintained long-term remissions increased to 20 (69%) (Table 1).

In a retrospective analysis, Tellier et al[12] assessed the long term outcome of RTX therapy for SDNS in 18 patients with a mean follow up of 3.2 yr. The children received one to four infusions of RTX during the first course of treatment, and subsequent infusions were given upon CD19 cell recovery (CD19 > 1%). A total of 22% of patients maintained remission without relapse. Ravani et al[13] performed a study to assess whether RTX can be safely and repeatedly used as prednisone and CNI-sparing therapy in children with dependent forms of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Approximately 46 patients were enrolled in the study; all received one to five RTX infusions. The probability of remission without the use of immunosuppressants was 48% and 20% at 6 and 12 mo, respectively, after RTX treatment (Table 1).

Sun et al[14] also showed that RTX was effective in maintaining remission in children with nephrotic syndrome. RTX treatment led to a statistically significant reduction in steroid dosage (P = 0.014); the number of recurrences was also significantly reduced (P < 0.001) with RTX therapy (Table 1).

A Scottish study involving seven children[15] with steroid-dependent disease showed that two doses of RTX (750 mg/m2) given 2 wk apart were effective in maintaining remission in six children (Table 1).

Prytula et al[16], in a multicenter questionnaire study, demonstrated that RTX therapy could elicit a response rate of 82 % in SDNS.

It is important to note that different studies have proposed differing numbers of initial RTX infusions. Hence, based on past evidence, it is difficult to comment on the optimum number of RTX infusions. Kemper et al[8] noted that 3-4 initial infusions of RTX were not associated with better or prolonged remission rates, compared to 1-2 initial RTX infusions.

The optimal RTX treatment strategy is also unclear. In a few past studies, RTX was given prophylactically upon B-cell recovery; in other studies, RTX therapy was begun only in cases of relapse. Tellier et al[12] showed that the time between two relapses was significantly shorter in patients who were retreated upon B-cell recovery compared to those who were not re-treated. This indicates that pre-emptive treatment at the time of B-cell recovery may help to maintain prolonged remission.

The use of RTX at regular intervals is another therapeutic approach. Kimata et al[17] demonstrated that RTX infusion at 3-mo intervals for a total of four doses is an effective strategy in maintaining remission and steroid-free periods. In this study, the annual number of relapses before administration was 1.4 (1.1-3.5) times/year. After administration, the number of relapses had decreased to 0.0 (0.0-0.0) times/year. Median steroid dosage before administration was 0.80 (0.23-0.96) mg/kg per day but was 0.00 (0.00-0.00) mg/kg per day after administration. All changes were statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Fujinaga et al[18] gave a single infusion of RTX (375 mg/m2) to 29 children with steroid/calcineurin inhibitor-dependent nephrotic syndrome. After RTX, 16 patients received MMF, and 13 patients received cyclosporine (CsA) as maintenance therapy. Cyclosporine was superior to MMF in maintaining remission. Treatment failure occurred more frequently in the MMF group (7/16) than in the CsA group (2/13). The rate of sustained remission was also significantly higher in the CsA group than in the MMF group (P < 0.05).

The evidence described above shows that RTX is an effective agent in children with SDNS/frequently relapsing disease, both in terms of maintaining prolonged remission and decreasing steroid exposure. However, common drawbacks of most such studies have been the small sample size and the lack of patients with nephrotic syndrome who were receiving conventional treatments or placebo (i.e., control groups). This highlights the need for more robust randomized controlled studies to assess the efficacy, safety and optimal dosing patterns of RTX.

The treatment of steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome is a challenge for clinicians. The disease has genetic causes in one-quarter to one-third of such patients[19]; patients with genetic aberrations do not benefit from immunosuppressive treatment.

In a randomized controlled study conducted between 2007-2010, Magnasco et al[20] evaluated RTX in 31 children with SRNS and a median age of 8 years (2-16 years). All patients were negative for the nephrotic syndrome 2 (NPHS2) and WT-1 mutations. Renal biopsy revealed that focal segmental glomerulosclerosis was the most common histological diagnosis in 19 patients (61%), followed by minimal change disease in 7 patients (23%). Patients were divided into 2 groups; the control group included 15 patients who continued conventional immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone and cyclosporine, and the interventional group included 16 patients who continued treatment with prednisone and cyclosporine, as well as receiving 2 doses of RTX. RTX did not reduce proteinuria at 3 mo, and the results of the study did not support the addition of RTX to prednisone and calcineurin inhibitors in children with SRNS (Figure 1). Histological diagnosis did not affect outcomes or response to RTX treatment (Table 1).

Gulati et al[7] assessed the efficacy of RTX in 33 pediatric patients with SRNS (24 with initial resistance and 9 with late resistance). Treatment consisted of 4 weekly doses of RTX (375 mg/m2 each). All patients but five were screened for NPHS1 and NPHS2. Nine patients (27.2%) achieved complete remission, 7 patients (21.2%) achieved partial remission, and 17 patients (51.5%) had no response. The median time to response was 32 days (range, 8 to 60 d) after the last dose of RTX. At the 6-mo follow up, all 16 patients remained in remission (complete or partial). The remission rate was higher in patients with minimal change disease (64.7%) than in those with FSGS (31.2%; P = 0.08) (Table 1).

Prytula et al[16] conducted a multicenter, questionnaire-based study to assess the initial response to RTX in children with SRNS and determined the initial response to be 44 %. However, a randomized study conducted by Magnasco et al[20] showed no benefit from RTX therapy.

In an assessment of five children with SRNS, Bagga et al[21] showed that 4 RTX doses of 375 mg/m2 were effective in achieving complete remission in four patients, while one patient achieved partial response. The mean ratio of urinary protein to creatinine was 8.3 at baseline and 0.8 at follow-up (P = 0.02, by analysis of variance), and the mean serum albumin level rose from 1.4 to 3.4 g per deciliter (P < 0.01).

It can be inferred from the findings of the studies included here that RTX therapy is less efficacious in the treatment of SRNS than in the steroid-dependent/frequently relapsing form of the disease. Cravedi et al[22] attributed the low serum level of RTX in patients with SRNS to urinary loss of RTX in these patients during the nephrotic state of the disease (not during remission). In addition, mutations in genes that encode an essential protein in the slit diaphragm of the glomerular filter play an important etiological role in patients with SRNS.

RTX has been used over the last few years for the treatment of complicated cases of pediatric nephrotic syndrome and has shown promising clinical efficacy.

However, questions regarding its safety and long-term effects in this particular group of patients have remained unanswered. A few previous uncontrolled studies have shown that RTX was well tolerated in pediatric patients with the steroid-dependent and resistant forms of nephrotic syndrome. Most adverse events were mild infusion-related reactions and resolved either spontaneously or with intramuscular epinephrine. Very few patients developed severe anaphylactic reactions, hypotension or cardiac arrhythmia[5]. The pathogenesis of such reactions is still unclear but may be related to cytokine release from the destroyed B cells.

Gulati et al[7] treated 33 pediatric patients with RTX (24 with SDNS, 9 with SRNS); only 4 patients (12%) developed infusion reactions (3 had chills and 1 had myalgia).

Another study of 30 patients from France[6] showed that 14 patients (47%) developed infusion-related reactions that were mild and did not require RTX discontinuation. Kemper et al[8] treated 37 patients with RTX, and only 2 patients developed itching at the first infusion. It is difficult to comment on the reasons for the differences in the number of adverse reactions noted among different studies. Bitzan et al[23] reported a patient with an RTX-related lung injury that resolved without any serious sequelae. There are more than 30 published reports (with 62 cases) of delayed pulmonary toxicities after RTX treatment. These have mostly been reported in adult patients with hematologic malignancies. RTX-related pulmonary toxicities can be serious and carry a significant mortality rate. Delayed pulmonary toxicities have not been reported in other clinical studies of pediatric nephrotic syndrome patients treated with RTX. However, Kamei et al[24] reported mild acute respiratory events during RTX infusion in 10/28 patients (36%). Sellier-Leclerc et al[6] reported adverse reactions in two nephrotic syndrome patients receiving RTX. Of these, one developed transient severe neutropenia, and the other developed transient thrombocytopenia. In general, hematological adverse events were uncommon and had no serious clinical effects. Serious infections were rare. Guigonis et al[5] reported that in a multicenter study of RTX in 22 patients, one patient developed Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) despite PCP prophylaxis. This patient was also receiving tacrolimus and corticosteroids at the time of PCP infection.

In a multicenter questionnaire-based study, Prytula et al[16] showed that 3/70 patients receiving RTX developed serious infections; one patient had agranulocytosis with sepsis, and two patients had pneumonia.

Kari et al[25] studied 4 patients receiving RTX for SRNS and reported that one patient developed clinical peritonitis. Of interest, a few patients developed fever of unknown origin after RTX without a clear microbial cause[5].

Data regarding the safety of RTX are not limited to pediatric patients with nephrotic syndrome. Several other research reports have also delved into the safety aspects of RTX therapy in adults. For example, RTX was well tolerated and generally found safe among patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and very few patients experienced serious adverse events. Data from the German national registry[26] revealed that out of 370 adult patients who received RTX for various immunological diseases, the overall rate of serious infections was 5.3 per 100 patient-years during RTX therapy. Opportunistic infections were infrequent across the whole study population and mostly occurred in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. There were 11 deaths (3.0% of patients) after RTX treatment. Sellier-Leclerc et al[27] reported a case of fulminant myocarditis after 4 mo of RTX infusion in a child with nephrotic syndrome who survived after receiving a heart transplant.

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is a serious demyelinating disease of the central nervous system arising from reactivation of the John Cunningham virus. It has been reported in various immunologic diseases[28] and with the use of various biological agents, including RTX. This is has not been reported in pediatric patients with nephrotic syndrome who were treated with RTX.

RTX has shown a reasonable safety profile in other pediatric autoimmune diseases. A systemic analysis of the use of RTX in children with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura[29] showed that in 11 studies (190 patients), a total of 78 (41.1%) patients experienced adverse events.

This review allows us to conclude that RTX appears to be an effective therapy that maintains remission in children with SDNS who failed to respond to other medications. The role of rituximab in children with SRNS needs to be evaluated further, as there are conflicting results regarding its efficacy in this group of patients. More randomized controlled studies are before recommending rituximab as a rescue therapy in children with SRNS. RTX seems to be safe in children with nephrotic syndrome, and the main adverse events are related to infusion reactions. However, close monitoring for long-term side effects is recommended.

| 1. | Kyrieleis HA, Löwik MM, Pronk I, Cruysberg HR, Kremer JA, Oyen WJ, van den Heuvel BL, Wetzels JF, Levtchenko EN. Long-term outcome of biopsy-proven, frequently relapsing minimal-change nephrotic syndrome in children. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1593-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ehrich JH, Geerlings C, Zivicnjak M, Franke D, Geerlings H, Gellermann J. Steroid-resistant idiopathic childhood nephrosis: overdiagnosed and undertreated. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2183-2193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Di Gaetano N, Cittera E, Nota R, Vecchi A, Grieco V, Scanziani E, Botto M, Introna M, Golay J. Complement activation determines the therapeutic activity of rituximab in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;171:1581-1587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Golay J, Zaffaroni L, Vaccari T, Lazzari M, Borleri GM, Bernasconi S, Tedesco F, Rambaldi A, Introna M. Biologic response of B lymphoma cells to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab in vitro: CD55 and CD59 regulate complement-mediated cell lysis. Blood. 2000;95:3900-3908. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Guigonis V, Dallocchio A, Baudouin V, Dehennault M, Hachon-Le Camus C, Afanetti M, Groothoff J, Llanas B, Niaudet P, Nivet H. Rituximab treatment for severe steroid- or cyclosporine-dependent nephrotic syndrome: a multicentric series of 22 cases. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1269-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sellier-Leclerc AL, Macher MA, Loirat C, Guérin V, Watier H, Peuchmaur M, Baudouin V, Deschênes G. Rituximab efficiency in children with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1109-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gulati A, Sinha A, Jordan SC, Hari P, Dinda AK, Sharma S, Srivastava RN, Moudgil A, Bagga A. Efficacy and safety of treatment with rituximab for difficult steroid-resistant and -dependent nephrotic syndrome: multicentric report. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2207-2212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kemper MJ, Gellermann J, Habbig S, Krmar RT, Dittrich K, Jungraithmayr T, Pape L, Patzer L, Billing H, Weber L. Long-term follow-up after rituximab for steroid-dependent idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1910-1915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shalhoub RJ. Pathogenesis of lipoid nephrosis: a disorder of T-cell function. Lancet. 1974;2:556-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 597] [Cited by in RCA: 601] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kemper MJ, Meyer-Jark T, Lilova M, Müller-Wiefel DE. Combined T- and B-cell activation in childhood steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Clin Nephrol. 2003;60:242-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Iijima K, Sako M, Nozu K, Mori R, Tuchida N, Kamei K, Miura K, Aya K, Nakanishi K, Ohtomo Y. Rituximab for childhood-onset, complicated, frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome or steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1273-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tellier S, Brochard K, Garnier A, Bandin F, Llanas B, Guigonis V, Cailliez M, Pietrement C, Dunand O, Nathanson S. Long-term outcome of children treated with rituximab for idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:911-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ravani P, Ponticelli A, Siciliano C, Fornoni A, Magnasco A, Sica F, Bodria M, Caridi G, Wei C, Belingheri M. Rituximab is a safe and effective long-term treatment for children with steroid and calcineurin inhibitor-dependent idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2013;84:1025-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sun L, Xu H, Shen Q, Cao Q, Rao J, Liu HM, Fang XY, Zhou LJ. Efficacy of rituximab therapy in children with refractory nephrotic syndrome: a prospective observational study in Shanghai. World J Pediatr. 2014;10:59-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | El Koumi M. Rituximab in steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2013;7:502-506. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Prytula A, Iijima K, Kamei K, Geary D, Gottlich E, Majeed A, Taylor M, Marks SD, Tuchman S, Camilla R. Rituximab in refractory nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:461-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kimata T, Hasui M, Kino J, Kitao T, Yamanouchi S, Tsuji S, Kaneko K. Novel use of rituximab for steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome in children. Am J Nephrol. 2013;38:483-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fujinaga S, Someya T, Watanabe T, Ito A, Ohtomo Y, Shimizu T, Kaneko K. Cyclosporine versus mycophenolate mofetil for maintenance of remission of steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome after a single infusion of rituximab. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:513-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Santín S, Bullich G, Tazón-Vega B, García-Maset R, Giménez I, Silva I, Ruíz P, Ballarín J, Torra R, Ars E. Clinical utility of genetic testing in children and adults with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1139-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Magnasco A, Ravani P, Edefonti A, Murer L, Ghio L, Belingheri M, Benetti E, Murtas C, Messina G, Massella L. Rituximab in children with resistant idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1117-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bagga A, Sinha A, Moudgil A. Rituximab in patients with the steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2751-2752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cravedi P, Ruggenenti P, Sghirlanzoni MC, Remuzzi G. Titrating rituximab to circulating B cells to optimize lymphocytolytic therapy in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:932-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bitzan M, Anselmo M, Carpineta L. Rituximab (B-cell depleting antibody) associated lung injury (RALI): a pediatric case and systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:922-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kamei K, Ito S, Nozu K, Fujinaga S, Nakayama M, Sako M, Saito M, Yoneko M, Iijima K. Single dose of rituximab for refractory steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:1321-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kari JA, El-Morshedy SM, El-Desoky S, Alshaya HO, Rahim KA, Edrees BM. Rituximab for refractory cases of childhood nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:733-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tony HP, Burmester G, Schulze-Koops H, Grunke M, Henes J, Kötter I, Haas J, Unger L, Lovric S, Haubitz M. Safety and clinical outcomes of rituximab therapy in patients with different autoimmune diseases: experience from a national registry (GRAID). Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sellier-Leclerc AL, Belli E, Guérin V, Dorfmüller P, Deschênes G. Fulminant viral myocarditis after rituximab therapy in pediatric nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:1875-1879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tan CS, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and other disorders caused by JC virus: clinical features and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:425-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 623] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Liang Y, Zhang L, Gao J, Hu D, Ai Y. Rituximab for children with immune thrombocytopenia: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Nihalani D, Tanaka H, Salvadori M S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL