Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.110750

Revised: June 23, 2025

Accepted: August 1, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 140 Days and 6.2 Hours

Roberts syndrome (RS) is a rare autosomal recessive cohesinopathy caused by biallelic mutations in ESCO2, essential for sister chromatid cohesion and genomic stability. Clinically, RS manifests as severe pre- and postnatal growth restriction, tetraphocomelia, craniofacial anomalies, and variable visceral organ malformations. Prenatal suspicion is often raised by ultrasonographic evidence of limb reduction and fetal hypotrophy. However, diagnosis remains elusive without molecular confirmation. This case underscores the diagnostic and prognostic value of next-generation sequencing in suspected RS, particularly within consanguineous populations where autosomal recessive conditions are more prevalent.

A four-month-old male infant, born to consanguineous parents, was referred for evaluation of multiple congenital anomalies. Prenatal ultrasonography demon

This case supports redefining isolated limb anomalies as early indicators warranting targeted prenatal genetic screening for cohesinopathies like RS.

Core Tip: Roberts syndrome is a rare but severe autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the ESCO2 gene, characterized by limb malformations, growth restriction, and multisystem involvement. This case highlights the urgent need for early detection through integrated prenatal imaging and genetic testing, especially in consanguineous families, to enable timely diagnosis, guide clinical management, and support informed reproductive decision-making.

- Citation: Sulaiman SA, Kaylani L, Manaseer Q, Mohammed DK. Exploring Roberts syndrome, unique manifestations in a four-month-old infant and genetic findings: A case report. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(4): 110750

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i4/110750.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.110750

Roberts syndrome (RS) is considered a rare, autosomal recessive disorder caused by biallelic mutations in a gene encoding for a protein which regulates sister chromatid cohesion and cohesion homologue 2 (ESCO2) and its es

RS is characterized by prenatal and postnatal growth restrictions, tetraphocomelia, distinctive craniofacial defects, and mental retardation[1]. However, the phenotypic spectrum of RS varies significantly, ranging from mild ranges from mild upper limb involvement to severe malformation syndromes and evident on prenatal ultrasonography[2,9]. Lower limbs are usually less frequently and severely affected relative to the upper limbs, yet both appear in a symmetrical pattern[7,8]. Other anomalies, including congenital heart defects, large genitalia, and cystic kidney have also been reported in patients[8]. Van den Berg and Francke devised a severity scoring system comprising of six criteria: (1) Growth retardation; (2) Phocomelia of upper limbs; (3) Phocomelia of lower limbs; (4) Survival; (5) Craniofacial malformations; and (6) Malformations of the palate, each assigned a score according to its severity. Patients with scores > 0.5 usually present with multiple severe malformations while scores 0.5 and -0.5 indicate severe malformations alongside milder findings[3]. Okpala et al[7] noted that infants with severe forms of the syndrome often die in utero, immediately at birth or otherwise shortly after, frequently due to cardiac, renal, and infections, meanwhile patients with milder forms could survive into adulthood.

The management of RS patients usually involves the management of phenotypic manifestations in addition to periodic assessment of the patient over time. The aim of individualized treatment is improving quality of life and could include correction of limb abnormalities, surgery for cleft lip and/or palate, prostheses, and speech assessment and special education in case of observed developmental delay[10]. Cardiac, renal, and ophthalmologic, cardiac, and renal abnormalities are also treated individually as indicated. As for surveillance, growth and development, motor and language development, and educational needs are all periodically assessed[10].

This case report therefore details the clinical, genetic, and the radiologic findings in a four-month-old male infant with RS, highlighting the necessity of integrating multimodal diagnostic approaches, combining early genetic testing with detailed clinical and radiological assessment, to achieve accurate and timely diagnosis.

A four-month-old male infant presented to the orthopedics clinic at the Jordan University Hospital, Amman, Jordan for the evaluation of multiple congenital limb anomalies since birth.

The patient presented complaining of phocomelia, short limbs, aplastic thumbs, and flexion contractures of both knees and elbows.

The mother, a healthy 23-year-old, non-smoker with no history of alcohol or drug use, experienced an unremarkable pregnancy until routine ultrasound examination at 22 weeks of gestation revealed short limbs and bilaterally absent radius and ulna. Follow-up ultrasonography at 38 weeks of gestation also revealed hydronephrosis of the left kidney. On all routine ultrasound examinations, the fetus appeared smaller in size considering the expected size at gestational age.

The infant is the first child of healthy, first-degree consanguineous parents. He was delivered via cesarean section at 40 weeks of gestation following a failed induction. At birth, the patient weighed 2.18 kg, measured 35 cm in length, and had a head circumference of 30 cm—parameters all below the 3rd percentile for gestational age.

Due to concerns regarding multiple congenital anomalies, he was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for observation and stabilization for six days.

Family history is notable for a paternal uncle who exhibited similar features and died at six weeks of age, raising early clinical suspicion of a genetic syndrome, particularly RS.

At the time of presentation, the infant’s weight, height, and head circumference were 4.3 kg, 45 cm tall, and 35 cm, respectively.

Craniofacial examination revealed microcephaly, a midline forehead hemangioma, sclerocornea, corneal haze, and blue sclera (Figure 1). Additional dysmorphic features included premaxillary protrusion, hypoplastic alae nasi, a high-arched palate, and micrognathia.

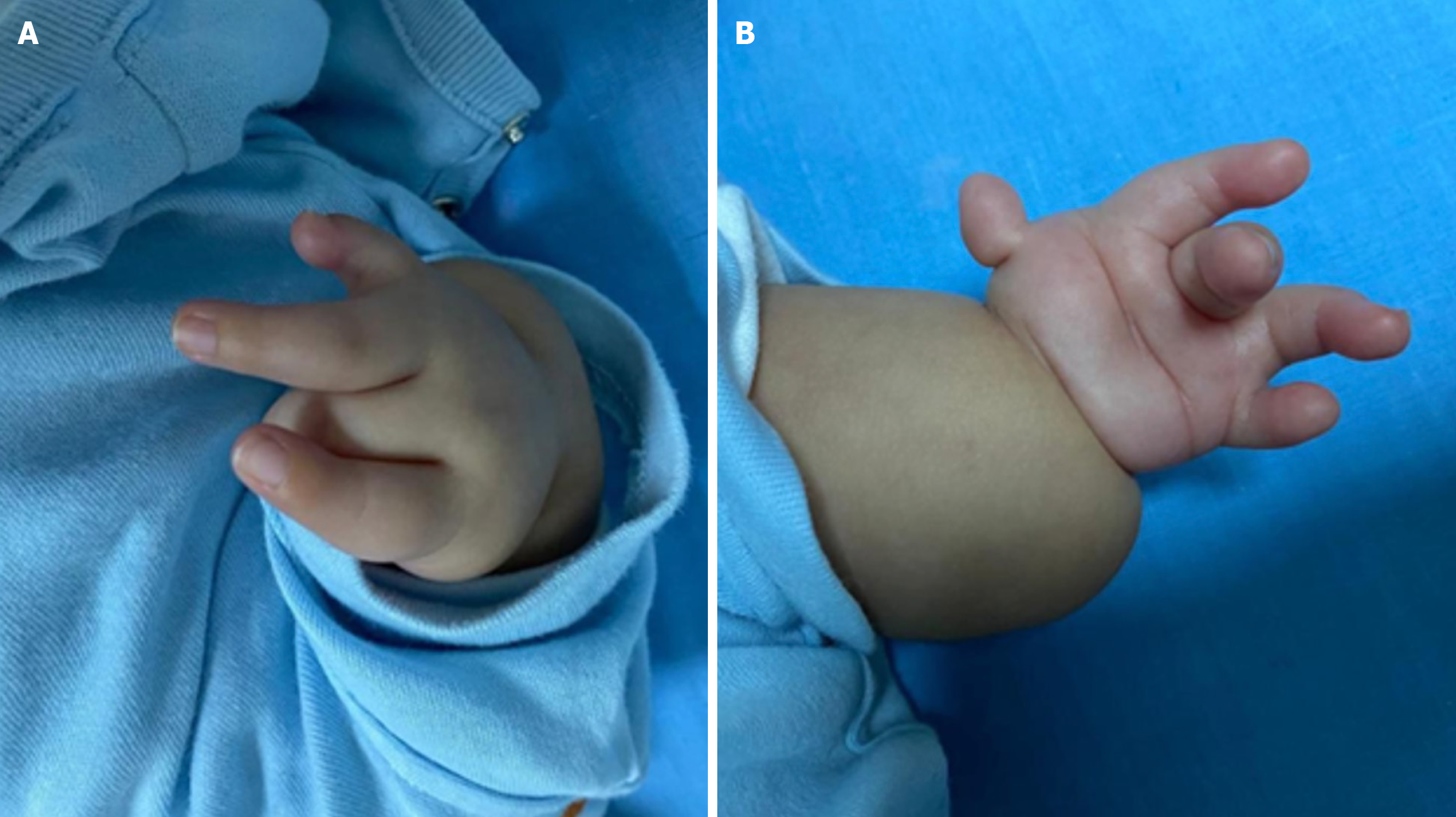

Genital examination was notable for undescended testes. Skeletal evaluation showed bilateral symmetrical phocomelia, right-handed oligodactyly, clinodactyly, thumb aplasia (Figure 2A), and left- handed thumb hypoplasia (Figure 2B). Lower limb abnormalities were also apparent (Figure 3).

In light of the clinical presentation, consanguineous parentage, and positive family history, a genetic workup was performed. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) confirmed a homozygous mutation in the ESCO2 gene, consistent with RS.

Cardiological assessment by echocardiography confirmed the presence of an atrial septal defect (ASD) and a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Brain computed tomography was unremarkable. Developmental evaluation revealed milestone acquisition appropriate for age.

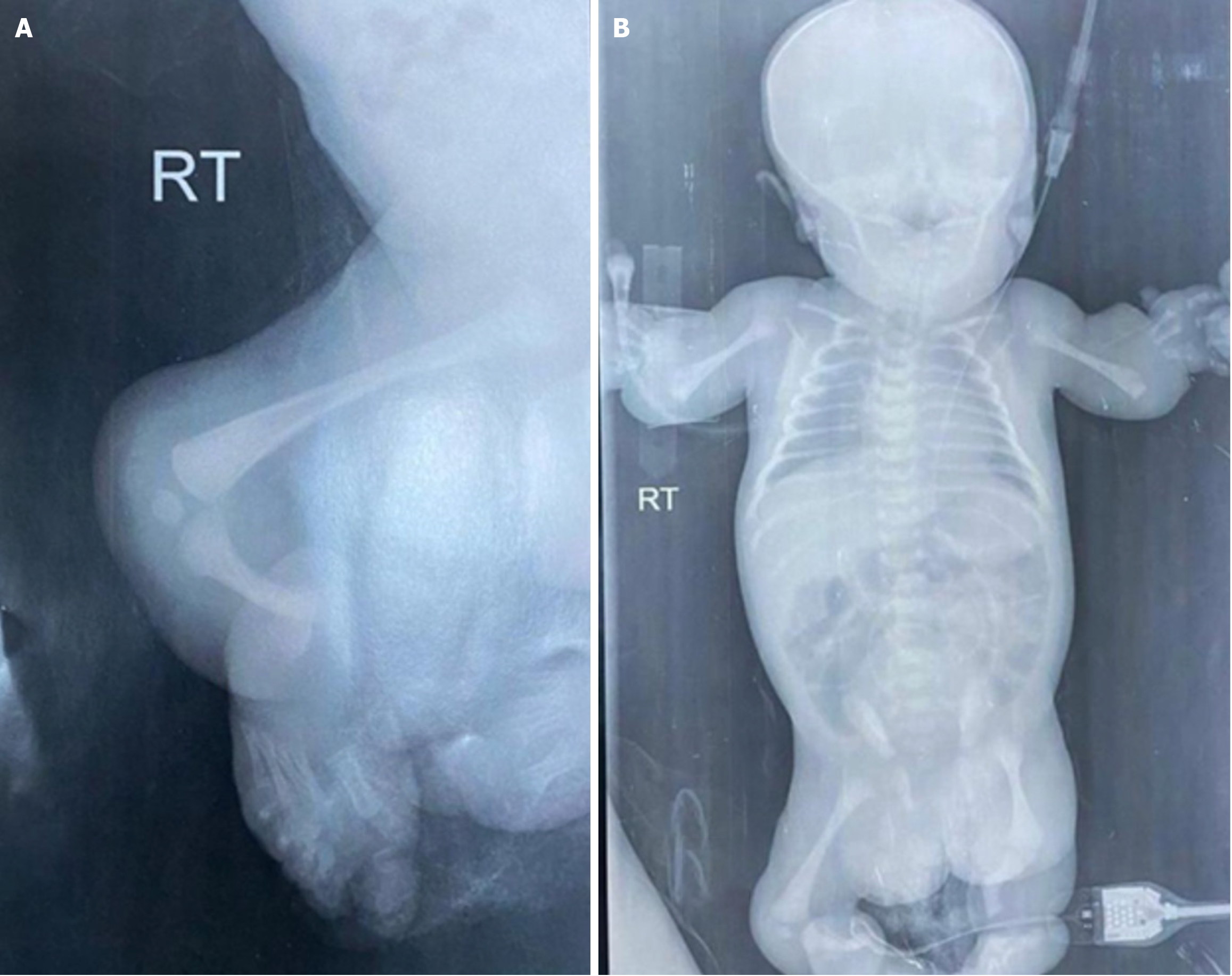

Radiographic imaging revealed several characteristic skeletal anomalies. In the upper extremities, there was complete bilateral absence of the radius and ulna. In the lower limbs, the fibula was absent on the right side, accompanied by abnormal development of the foot bones (Figure 4A). Pelvic imaging demonstrated a shallow right acetabulum and a non-developed left acetabulum with superior displacement of the left femoral head, forming a pseudoacetabulum. A comprehensive overview of the skeletal anomalies is presented in the full-body bone survey (Figure 4B).

A final diagnosis of RS was established based on the phenotypic presentation and genetic identification of a homozygous mutation in ESCO2 via WES.

The management approach is primarily symptomatic and multidisciplinary, involving orthopedics, genetics, and developmental pediatrics. Moreover, family counseling was initiated to address genetic implications, future reproductive planning, and psychosocial support.

The patient is currently under ongoing evaluation to determine a tailored surgical and rehabilitative plan, where the prognosis is dependent on the severity of functional limitations and associated anomalies. Additionally, follow-up is focused on procedural planning, functional assessments, and continued support for the family.

This case demonstrates typical clinical features seen in RS patients, with the diagnosis confirmed by identifying a pathological variant of the ESCO2 gene, the underlying genetic cause of this rare cohesinopathy.

While molecular genetic testing remains the cornerstone for confirming RS, a subset of patients with RS-like phenotypes lack detectable ESCO2 mutations-referred to as “pseudo-Roberts syndrome”-highlighting that phenotypic evaluation remains essential[1,3-5,10]. This highlights the indispensable role of thorough phenotypic evaluation and reinforces the importance of a multimodal diagnostic strategy that integrates genetic testing with comprehensive clinical and radiological assessment, especially in the context of consanguinity.

Since most characteristic features of RS manifest as structural fetal anomalies, prenatal ultrasonography serves as a valuable early diagnostic tool[6]. Paladini et al[9] demonstrated that even in the absence of a positive family history, ultrasonographic findings can suggest RS, enabling timely suspicion and further evaluation. Main prenatal ultrasonographic findings are short limbs and intrauterine growth retardation in RS patient[5]. Similarly, our study showed that prenatal imaging revealed bilateral absence of the radii and ulnae, significant growth restriction, and left kidney hydronephrosis, findings consistent with typical RS phenotype. Renal anomalies are variably reported in 12%–50% of RS cases, with hydronephrosis being one of the more frequently observed abnormalities[11], making each case unique in its presentation, which requires maintaining a high index of suspicion to avoid missing the diagnosis in these patients.

Additionally, since management primarily depends on the manifestations present in each patient, a holistic approach is essential in the assessment of RS. For instance, some ocular manifestations in RS are common, including hypertelorism, exophthalmia, and corneal clouding, reported in up to 86.7%, 69.4%, and 68.1% of cases respectively[11]. While congenital glaucoma is rarely associated with RS, some reports have documented its presence in approximately 8% of patients[11]. In this case, our patient did not exhibit glaucoma, aligning with the majority of literature which has yet to establish a definitive association. However, in this case report, the patient presented with blue sclera, found to be associated with over 60 genetic syndromes, which highlights the role systemic evaluation plays in timely diagnosis and mitigating misdiagnosis[12]. This also underscores the value of exploring whether or not long-term prognosis is different between patients with certain RS features than others. Regarding cardiac abnormalities, atrial and ventricular septal defects are seen in 29% of RS patients, as seen in our case revealing ASD as well as PDA[13]. Despite our patient presenting an absence of neurological findings, RS patients may present with cerebrovascular disease, yet on rare occasions, with stroke, arterial occlusion, cavernous hemangioma of the optic nerve, optic atrophy, and Moyamoya disease. He et al[14] have reported the death of a 13 year old patient with confirmed biallelic ESCO2 mutation as a result of a cerebellar hemorrhage secondary to an aneurysm, with a previous ischemic stroke at six-years-old notes, which further indicates the need for a comprehensive assessment in RS patients.

Furthermore, although the consanguinity is frequently observed in RS, including this patient’s family, non-consanguineous cases are still observed, as seen in a case of a 13-year-old girl reported by Almulhim et al[11]. Additionally, considerable phenotypic variability exists both within and between families harboring ESCO2 mutations, complicating efforts to establish clear genotype-phenotype correlations and making clinical prognosis challenging[3]. Therefore, despite phenotypic variability between patients, no association has been reported between specific phenotypic features and different ESCO2 variants[13]. While our case underscores the critical role of early genetic testing—particularly in consanguineous families—it still lacks follow-up data, which is essential in providing a deeper understanding on the prognosis and long-term outcomes of patients and improving their quality of life. Future research should aim to elucidate the factors contributing to disease severity and to define clearer relationships between genotype and phenotype in RS.

In conclusion, this case highlights the essential role of a comprehensive, multimodal approach in diagnosing and managing RS. Early integration of prenatal imaging, clinical assessment, and molecular genetic testing is vital, particularly in high-risk populations such as consanguineous families. Given the complexity and variability of RS, individualized care plans and multidisciplinary involvement are necessary for optimal outcomes. Moreover, genetic counseling remains a cornerstone of care for at-risk families to support informed reproductive decision-making and early diagnosis in future pregnancies.

| 1. | McKay MJ, Craig J, Kalitsis P, Kozlov S, Verschoor S, Chen P, Lobachevsky P, Vasireddy R, Yan Y, Ryan J, McGillivray G, Savarirayan R, Lavin MF, Ramsay RG, Xu H. A Roberts Syndrome Individual With Differential Genotoxin Sensitivity and a DNA Damage Response Defect. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103:1194-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goh ES, Li C, Horsburgh S, Kasai Y, Kolomietz E, Morel CF. The Roberts syndrome/SC phocomelia spectrum--a case report of an adult with review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:472-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Afifi HH, Abdel-Salam GM, Eid MM, Tosson AM, Shousha WG, Abdel Azeem AA, Farag MK, Mehrez MI, Gaber KR. Expanding the mutation and clinical spectrum of Roberts syndrome. Congenit Anom (Kyoto). 2016;56:154-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mfarej MG, Skibbens RV. An ever-changing landscape in Roberts syndrome biology: Implications for macromolecular damage. PLoS Genet. 2020;16:e1009219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dulnuan DJ, Matsuoka M, Uketa E, Hayashi K, Murotsuki J, Nishimura G, Hata T. Antenatal three-dimensional sonographic features of Roberts syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:241-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gruber A, Rabinerson D, Kaplan B, Ovadia Y. Prenatal diagnosis of Roberts syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 1994;14:511-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Okpala BC, Echendu ST, Ikechebelu JI, Eleje GU, Joe-Ikechebelu NN, Nwajiaku LA, Nwachukwu CE, Igbodike EP, Nnoruka MC, Okpala AN, Ofojebe CJ, Umeononihu OS. Roberts syndrome with tetraphocomelia: A case report and literature review. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221094077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen H. Roberts Syndrome. In: Atlas of Genetic Diagnosis and Counseling. Springer, New York, 2016. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Paladini D, Palmieri S, Lecora M, Perone L, Di Meglio A, D'Armiento M, Cascioli C, Martinelli P. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of Roberts syndrome in a family with negative history. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;7:208-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Salari B, Dehner LP. Pseudo-Roberts Syndrome: An Entity or Not? Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2022;41:396-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Almulhim A, Almoallem B, Alsirrhy E, Osman EA. Unique Roberts syndrome with bilateral congenital glaucoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:4635-4639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Brooks JK. A review of syndromes associated with blue sclera, with inclusion of malformations of the head and neck. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;126:252-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tae SK, Ra M, Thong MK. Case report: The evolving phenotype of ESCO2 spectrum disorder in a 15-year-old Malaysian child. Front Genet. 2023;14:1286489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | He S, Chen S, Li SJ, Zhang JW, Liang XL. Complex cerebrovascular diseases in Roberts syndrome caused by novel biallelic ESCO2 variations. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2023;11:e2177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/