Published online Nov 26, 2018. doi: 10.5321/wjs.v6.i2.11

Peer-review started: August 23, 2018

First decision: October 10, 2018

Revised: October 16, 2018

Accepted: November 13, 2018

Article in press: November 13, 2018

Published online: November 26, 2018

Processing time: 105 Days and 14.6 Hours

With an increase in the number of cases of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), dental professionals need to be aware of the different techniques required to ensure safe dental treatments for affected patients. The concerns and preferences of the parents and the medical and dental history of each patient should be considered. The aim of this article was to provide a comprehensive update on the medical and dental health of patients with ASD. A detailed search of the electronic database PubMed/Medline/Lilacs was performed for the terms “Autism”, “Autistic”, “Autism Spectrum Disorder”, “ASD”, “Dentistry” and “Dentist”, in the period between 2006 and 2017. Systemic reviews, research articles, and literature reviews were included. Expert opinions, case series, and case reports were excluded from the search. A detailed family-centered approach based on the preferences and concerns of parents is an important foundation for appropriate individualized dental treatment of patients with ASD. In addition, the knowledge of disruptive behaviors and patient´s challenges may guide dental practitioners in improving treatment planning, oral management, and the overall oral health of patients with ASD.

Core tip: The number of patients diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder is increasing and the behavioral disorders of these patients can prove challenging during dental treatment. This literature review concluded that desensitization techniques and a patient-centered individual approach with the support of family could make dental treatments less stressful, less time consuming, and more successful.

- Citation: Czornobay LFM, Munhoz EA, Lisboa ML, Rath IBS, de Camargo AR. Autism spectrum disorder: Review of literature and dental management. World J Stomatol 2018; 6(2): 11-18

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6263/full/v6/i2/11.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5321/wjs.v6.i2.11

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) published in 2013[1], provides the most current diagnostic criteria for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The term is used to describe neurodevelopmental disorders that were previously classified as autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive neurodevelopmental disorder not otherwise specified[2].

The term spectrum represents a group of disorders with symptoms that are seen on a continuum, which ranges from mild to severe expression[2]. All of them are related to difficulties due to deficits in social and emotional reciprocity, the ability to start and maintain relationships, and the use of non-verbal communication; marked by stereotyped and repetitive behaviors, with restricted interests, and allied to hyper and/or hypo sensorial hyposensitivity[1].

According to Bernier et al[3] the disorder affects between 1 in 68 and 1 in 50 American children in all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, and it is almost five times more likely to occur in boys than girls.

Current evidence suggests that dental treatment under general anesthesia in children with special needs, especially individuals with ASD, are performed majorly due to uncooperative behavior and the extensiveness of the dental treatment, both of which are judged objectively[4,5].

The objective of this study was to conduct a review of the literature illustrating the important aspects of dental management in patients with ASD.

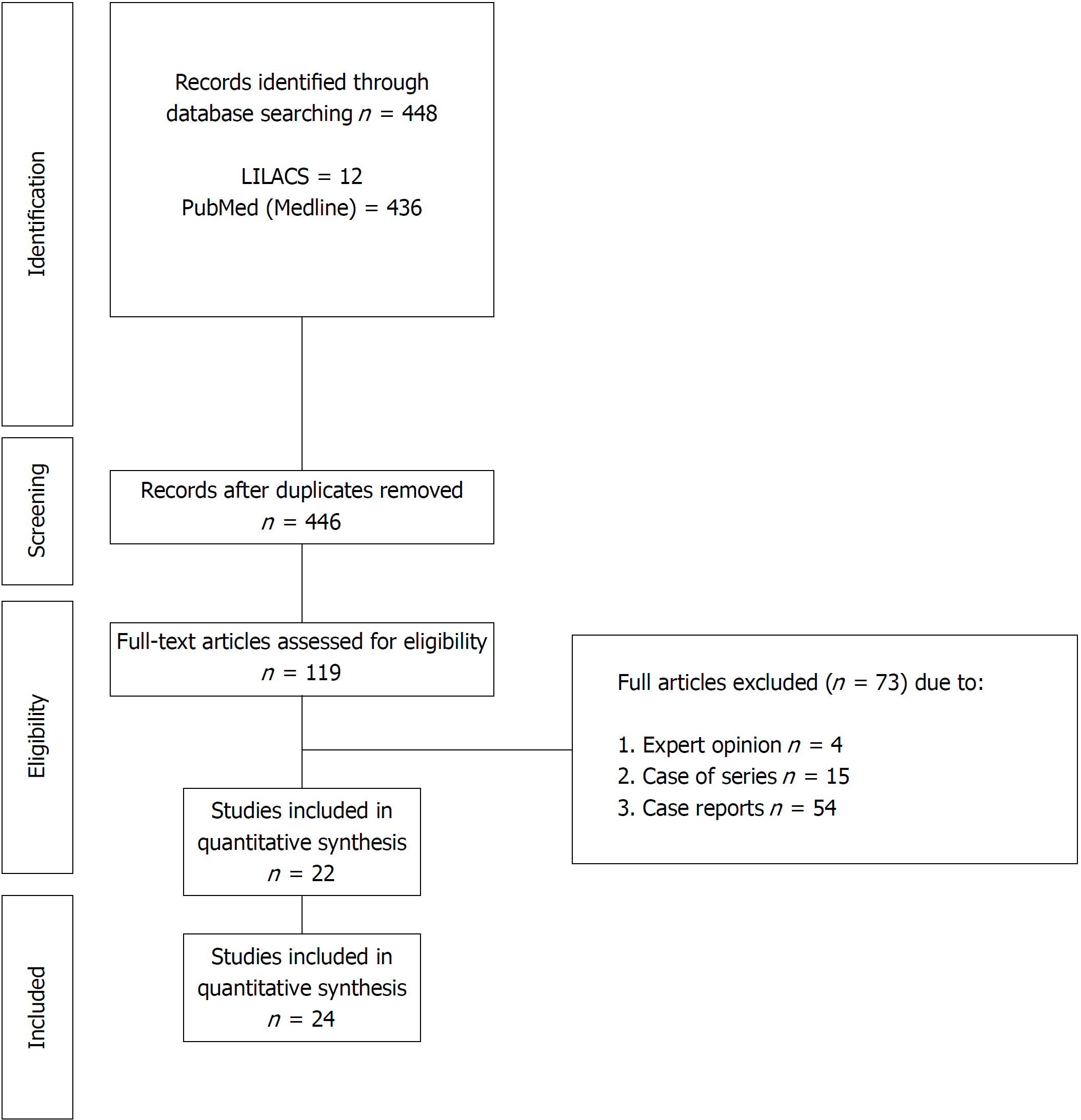

In order to conduct the proposed literature review, a bibliographic research was conducted in the database PubMed/MEDLINE/Lilacs with the following descriptors: “Autism”, “Autistic”, “Autism Spectrum Disorder”, “ASD”, “Dentistry”, and “Dentist”. The article search was restricted to the years 2006-2017. Systematic and non-systematic reviews and research articles were considered in this study. Articles such as expert opinions, case series, and case reports were disregarded for this review.

The initial search provided 358 articles from which 119 were selected based on their titles. This was further reduced to a final sample of 46 articles, after the main researcher perused the abstracts. Flow Diagram of Literature Search and Selection Criteria is available in Figure 1.

According to DSM-5 the ASD is classified into 3 levels of severity based on social interaction, communication, restricted interests, and repetitive behaviors[1].

Level 1 (Requiring support): Deficit in social communication capacity, difficulty in social interaction, and an apparent lack of interest in social relations. There is resistance in attempts to change or redirect interests[1].

Level 2 (Requiring substantial support): Greater deficit in the capacity of social communication both verbal and nonverbal, limited social initiation of interaction, and reduced or anomalous responses to social interactions. Individual become distressed or frustrated when their routine has changed[1].

Level 3 (Requiring very substantial support): Serious lack of social communication both verbal and nonverbal, very limited social initiation, and minimal responses to other people’s social proposals. Restricted interests and repetitive behaviors interfere significantly in other contexts. Individuals demonstrate high level of suffering when their routine has been altered[1].

Currently, there are no biological markers that are specific to children with the disorder, and diagnosis is based on observation of patient interaction, and detailed information from interviews (anamnesis) with parents and/or caregivers, observations made by the medical team, and a neurological exam to exclude medical comorbidities and/or psychiatric disorders[1,6].

The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADR-I) is considered the gold standard for ASD diagnosis. It is a questionnaire of 90 questions, which can be administered to parents and/or caregivers, by experts from different areas such as psychiatrists, neurologists and psychologists. Despite these advances, the mean age of diagnosis is still 4-5 years[7].

No specific etiology for ASD has been identified; therefore, there is a general tendency to credit multiple etiologies to the disorder[8,9]. Several hypotheses have been considered reduction in the number of Purkinje cells of the cerebellum[10], reduction in the connectivity between specialized local neural networks in the brain and possibly over connectivity within the isolated individual neural assemblies[11], mutations of the PTEN gene[12], contact with pesticides during pregnancy[13], paternal age above 35 years[14], and altered levels of chemokines and specific cytokines during pregnancy[15].

In the past, exposure to mercury and thimerosal present in vaccines represented an important etiological factor for the development of ASD[16]. However, in 1999, the American Academy of Pediatrics reduced the exposure to these substances, culminating in a significant reduction in the number of cases.

Individuals with ASD may face significant challenges in sensory processing and sensory integration (nervous system processes and response to information obtained through the five senses), displaying socially disruptive behaviors externalized in form of aggressiveness, or self-mutilation, and hyperactivity when exposed to sensations like noises or lights, contact with strangers, and taste of unknown foods, among other stimuli that overwhelm them[4,17,18]. According to researchers, 80%-100% of individuals have a differentiated way of processing information, actions, and stimuli from the social context. This difficulty in interpretation is attributed to the presence of eidetic memory, which results in the individual´s inability to extract the implicit context in everyday situations and actions[19]. Summary data are presented in Table 1.

| Type of sensory and behavioral difficulties | Description |

| Visuals | Interest in rotating, colored or moving objects; |

| Auditory | Changes in sensory processing manifested as hypo or hypersensitivity; |

| Tactile | Reactions exacerbated by textures, touches, clothes, shoes and difficulty performing daily activities such as brushing teeth, cutting nails and cutting hair; |

| Proprioceptive | Difficulties in feeling their body in space |

| Gustatory | In form of refusal of food; |

| Flapping | Enjoy hitting their arms excessively against some specific surface |

| Rocking | Enjoy hitting their whole body against some specific surface |

| Spinning | Enjoy spinning excessively |

| Excessive ordering and stiffness | Difficulty performing actions and activities outside of your routine |

| Escape, avoidance or isolation behavior | It is usually related to auditory hypersensitivity and stimulus overload; |

| Aggressiveness | Caused by or as a reflex of sensory overload; |

| Hyperfocus | The child usually has a deep concentration, observing only some details in the environment; |

| Difficulties of attention | It is believed that more than half of the children with autism spectrum disorder have behaviors compatible with attention deficit disorder and/ or hyperactivity. |

| Eidetic memory | The person has a mental photograph of an event in their memory |

| Dyspraxia | Difficulty in planning, sequencing and performing motor actions due to sensory problems |

It is extremely important to highlight that each individual is unique, with different characteristics and specificities; therefore, all possible stimuli and behaviors listed above must be relativized and individualized. Besides, the observation of a specific behavior only makes sense in a social context, and not in isolation[19].

Currently, there isn’t a single best treatment for ASD[20]. However, there is a diversity of drugs commonly prescribed for associated conditions, such as sleep disorders, epilepsy, gastrointestinal problems, and hyperactivity, amongst others[21].

It is very crucial that the dentist knows the medications prescribed by the medical team and studies the possible drug interactions with drugs commonly prescribed in dentistry[4].

Other therapeutic strategies consist of intensive and early behavioral intervention programs, applied with different techniques jointly or individually[22].

Desensitization consists of a series of procedures that are performed to repeatedly expose children with ASD to a controlled environment in order to promote their confidence and increase their adaptation, thus increasing their cooperation. The process begins with parents/caregivers using techniques of positive reinforcement, such as the use of a reward at the end of the consultation, and validating appropriate behavior[23].

The Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH) is still widely used in many parts of the world, since the 1960s. The program is based on the organization of the physical environment through pre-established routines, in which the use of pictures, panels, or agendas systematize daily tasks or work systems in order to facilitate the understanding of the environment[24]. The method promotes the independence of the child while simultaneously assisting parents/caregivers and teachers[24].

The analytical behavior treatment (ABA) aims to develop skills and abilities that are acquired in stages, by means of instructions or indications that predict the events or stimuli that precede a daily activity and its consequences. It is important that learning is pleasant and helps children to identify different stimuli. When necessary, additional support is offered, this should be removed as soon as possible, so as not to make children dependent on it. As an appropriate response is obtained, the child will receive a reward as a positive reinforcement. Repetition is an important factor in this type of approach, as is the exhaustive record of all trials and their results[25].

Social histories present a short description of a specific event, which combines descriptive and visual resources, and promotes appropriate behavior within the situation addressed[26]. The elaboration of a social history should begin with the selection of a specific theme, like a dental appointment, and should be explained using photos, figures, or drawings with short descriptive sentences mixed with phrases that indicate the desired behavior. An atmosphere of positivity is important for the success of therapy, and it is important to avoid negative phrases. Adequate social behavior can be attained by the reading frequency of the story[27].

Regardless of the technique used, the time required for the application of desensitization techniques represents the most difficult factor for professionals, since it requires both professional and family availability. Multi-professional work with occupational therapy, and simulated visits to the dentist, can minimize this disadvantage[28].

All of the above interventions are aimed at developing language, physical, and intellectual skills, and should consider the type of patient’s communication. It is important that the strategies be carried out on a continuous basis, often with a mix of therapies, taking into consideration, the maximum number of people who are part of the children’s routine[25].

The dental treatment of individuals with ASD has been a challenge for dental professionals. Barriers to dental treatment include difficulties in access to the health care system, uncooperative patient behavior, cost and lack of insurance[29,30].

A questionnaire administered to parents/caregivers of children with ASD recorded the most common complains as difficulty in getting to the dental office and increased waiting time in the waiting room for dental appointments[31]. The environment of the dental office and the care itself, acts as triggers for different sensory processing in some patients leading to possible socially disruptive behaviors. Materials commonly used in clinical practice, temperature variations, different smells, direct light on the eyes, physical exam, noisy environment, or a combination of different factors, can be stressful as well[28].

Moreover, the feeling of anxiety is often exacerbated by routine changes, such as going to the dental office, and could be expressed as social phobias or specific phobias (excessive fear of a noise, for example). Together, all these factors may result in difficulties in dental management, resulting in a frustrating and inefficient appointment for professionals, patients and family[28].

Difficulty in dental care management results in poor oral hygiene which is the main risk factor implicated in the development of oral diseases, such as caries and gingivitis[20,32,33].

A systematic review conducted by Bartolomé-Villar et al[34] shows that children with ASD and other sensory disturbances present with poor oral hygiene, with an increase in plaque and bleeding indexes as a result of poor hygiene. However, the study was not conclusive regarding the prevalence of caries and malocclusions.

Data about the prevalence of caries in ASD patients are divergent in the literature, and no correlation with comparatively worse oral hygiene was directly established[33]. The evaluation of the buffer capacity and the salivary flow rate were evaluated, and no correlation was verified[35]. On the other hand, high prevalence of caries in ASD patients was observed by Jabar[32]; DeMattei et al[36]; and Vishnu et al[37]. After reviewing 385 records of patients with ASD, Loo et al[38], observed a lower prevalence of dental caries in individuals with ASD.

In the first appointment to the dental clinic, the patient and parents/caregivers must discuss the future therapeutic approach with the dental team. Data collection in the form of communication, medical history, associated conditions, sensory triggers, oral hygiene habits, inappropriate social behaviors, and dental history including patient’s reaction to previous treatments, should be done. Consequently, the child’s strengths and potential obstacles to dental intervention will be discovered[4].

In some cases, it eventually becomes necessary to use general anesthesia to carry out dental treatment for individuals with ASD. General anesthesia can assist in providing quality dental care in many patients who cannot be treated otherwise[28,39,40]. In these situations, the systemic health conditions should be evaluated in conjunction with the anesthesiology team, and the cost/benefit issues of the therapy must be discussed with family and or caregivers[41].

It is important to highlight that the hospital environment may produce hypersensitive responses which can lead to a complicated period of hospitalization, thereby increasing the family’s and patient’s stress levels[42].

For families who are not comfortable with general anesthesia, the pharmacological sedation with benzodiazepines such as midazolam or diazepam can be used as an alternative since they it represents a good choice to achieve conscious sedation in dentistry, with low incidence of adverse reactions, and low costs[43].

Both techniques, conscious sedation and general anesthesia, do not promote the acceptance of dental interventions. Besides, they are associated with an increased risk of physical and psychological impairment; therefore, they should be reserved for cases where no other behavior orientation options are possible[5].

If an intervention program it is the best choice for a patient, it should be individualized to suit the individual´s characteristics, based on the professional experience and the resources available in the dental clinic. Therapy should be centered on family involvement[24], and the form of communication - verbal or non-verbal - must be considered.

According to Ferreira et al[44] and Chandrashekhar et al[45], the delay in language acquisition is an important marker of psychomotor development that is reflected in adults as lower intellectual development (intelligence quotient), lower cognition, and adaptive behavior. The form of communication may interfere with the processing of this information, and the professional should pay attention to facial expressions, body expressions, and gestures. If the patient can verbally communicate, it is important for the professional to have an idea of the amount of words he or she knows, in order to correlate the complexity of the subjects and activities that the patient can narrate or interact with during a conversation. The technique of voice control (a technique that uses different word intonations relating to the context and its meanings) can and should be attempted, but its real impact on behavioral improvement is uncertain, considering that some patients do not perceive the meaning of different voice intonations and facial expressions[4]. For patients who do not have verbal communication skills, communication strategies based on the application of symbols, images, and gestures can help in the understanding of potential sensory processing difficulties[4]. The dental team should be organized for changeable and atypical responses to sensory stimuli, as these patients dislike even minute changes in their surroundings and distractions must be avoided[45].

The primary objective of the dental surgeon should be to consider the patient’s autonomy and independence training in order to perform his/her daily routine of oral hygiene. The analysis of the type of communication - verbal or non-verbal - is essential for the individual work itself or together with parents/caregivers[34].

For the first non-invasive dental procedure some strategies may be tried in the pursuit of increased patient cooperation. The main objective should be to transform the dental clinic into a less aggressive place and depict the dental visits as part of routine life as well. Some suggested strategies may be[28,46]: (1) To value care and forms of communication provided by the patient, family and caregivers; (2) establish communication strategies that facilitate the dental treatment. The strategy must be family-centered; (3) use simple, short, and clear statements-avoid jargon, language figures, and metaphors, as ASD patients tend to be literal thinkers and have a hard time understanding symbolic language and language figures. Use a calm voice, with detailed explanations of each procedure, and minimize body contact; (4) teaching skills should be one of the objectives of dental treatment. For example, following the professional’s commands, testing different brushing techniques, using a hand or electric brush, and choosing a toothpaste with a tolerable taste; (5) be alert during the consultation in identification of trigger points for inappropriate behaviors; (6) mark the appointments in the first hour to reduce the risk of delays, as well as decrease the waiting room time; (7) avoid the use of flavored polish and fluoride pastes for patients extremely sensitive to taste; (8) patients can wear sunglasses to decrease light stimulation and/or earphones with portable music devices to decrease sensory stimuli during procedures; (9) promote familiarization with waiting room, dental clinic, and dental instruments. Personalized photographs or toys may be used as a desensitization strategy.

The dental treatment of patients with ASD requires knowledge of the individual’s behavioral profile. When commencing dental treatment, it is important that the professional collects data on the patient’s medical and dental history, as well as possible comorbidities and medications in use. Behavioral and emotional difficulties should be discussed with family and/or caregivers, and the dental treatment plan must be supported by the family and caregivers.

Making the dental appointment less aggressive for the patient with ASD should be the primary goal of the dentist. The professional should adopt a sensitive approach, and try to understand the world from the perspective of the individual, minimizing possible environmental triggers of disruptive behaviors, as well as knowing how to use different desensitization techniques in order to adapt the dental treatment to the individual needs of the patient, and always guided by family.

| 1. | American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders-DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. . |

| 2. | Lauritsen MB. Autism spectrum disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22 Suppl 1:S37-S42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Bernier R, Gerdts J, Munson J, Dawson G, Estes A. Evidence for broader autism phenotype characteristics in parents from multiple-incidence autism families. Autism Res. 2012;5:13-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nelson TM, Sheller B, Friedman CS, Bernier R. Educational and therapeutic behavioral approaches to providing dental care for patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Spec Care Dentist. 2015;35:105-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Polli VA, Sordi MB, Lisboa ML, Munhoz EA, Camargo AR. Dental Management of Special Needs Patients: A Literature Review. GJOS. 2016;2:33-45. |

| 6. | Mattila ML, Jussila K, Linna SL, Kielinen M, Bloigu R, Kuusikko-Gauffin S, Joskitt L, Ebeling H, Hurtig T, Moilanen I. Validation of the Finnish Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ) for clinical settings and total population screening. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:2162-2180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zwaigenbaum L, Penner M. Autism spectrum disorder: advances in diagnosis and evaluation. BMJ. 2018;361:k1674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chakrabariti S. Early identification of Autism. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:412-414. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Schaefer GB, Mendelsohn NJ; Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee. Clinical genetics evaluation in identifying the etiology of autism spectrum disorders: 2013 guideline revisions. Genet Med. 2013;15:399-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Palmen SJ, van Engeland H, Hof PR, Schmitz C. Neuropathological findings in autism. Brain. 2004;127:2572-2583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rippon G, Brock J, Brown C, Boucher J. Disordered connectivity in the autistic brain: challenges for the “new psychophysiology”. Int J Psychophysiol. 2007;63:164-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Reichow B. Overview of meta-analyses on early intensive behavioral intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:512-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shelton JF, Geraghty EM, Tancredi DJ, Delwiche LD, Schmidt RJ, Ritz B, Hansen RL, Hertz-Picciotto I. Neurodevelopmental disorders and prenatal residential proximity to agricultural pesticides: the CHARGE study. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:1103-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sandin S, Schendel D, Magnusson P, Hultman C, Surén P, Susser E, Grønborg T, Gissler M, Gunnes N, Gross R. Autism risk associated with parental age and with increasing difference in age between the parents. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:693-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jones KL, Croen LA, Yoshida CK, Heuer L, Hansen R, Zerbo O, DeLorenze GN, Kharrazi M, Yolken R, Ashwood P. Autism with intellectual disability is associated with increased levels of maternal cytokines and chemokines during gestation. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:273-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kern JK, Geier DA, Sykes LK, Haley BE, Geier MR. The relationship between mercury and autism: A comprehensive review and discussion. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2016;37:8-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Timoshenko LV, Khabrat BV. Possibilities of combined diathermo-cryodestruction in the treatment of hyperplastic processes of the cervix uteri. Akush Ginekol (Mosk). 1991;52-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lane AE, Young RL, Baker AE, Angley MT. Sensory processing subtypes in autism: association with adaptive behavior. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:112-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Marco EJ, Hinkley LBN, Hill SS, Nagarajan SS. Sensory Processing in Autism: A Review of Neurophysiologic Findings. Pediatr Res. 2011;69:48R-54R. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 779] [Cited by in RCA: 659] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gandhi RP, Klein U. Autism spectrum disorders: an update on oral health management. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14 Suppl:115-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Tchaconas A, Adesman A. Autism spectrum disorders: a pediatric overview and update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25:130-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Howlin P, Magiati I, Charman T. Systematic review of early intensive behavioral interventions for children with autism. Am J Intellectual Dev Disabil. 2009;114:23-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Delli K, Reichart PA, Bornstein MM, Livas C. Management of children with autism spectrum disorder in the dental setting: concerns, behavioural approaches and recommendations. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:e862-e868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Virues-Ortega J, Julio FM, Pastor-Barriuso R. The TEACCH program for children and adults with autism: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:940-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Foxx RM. Applied behavior analysis treatment of autism: the state of the art. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17:821-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Crozier S, Tincani M. Effects of social stories on prosocial behavior of preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:1803-1814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gray C. The new Social Story™ book. Revised and expanded 10th anniversary edition. Arlington: Future Horizons 2010; . |

| 28. | Klein U, Nowak AJ. Characteristics of patients with autistic disorder (AD) presenting for dental treatment: a survey and chart review. Spec Care Dentist. 1999;19:200-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lai B, Milano M, Roberts MW, Hooper SR. Unmet dental needs and barriers to dental care among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1294-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nelson LP, Getzin A, Graham D, Zhou J, Wagle EM, McQuiston J, McLaughlin S, Govind A, Sadof M, Huntington NL. Unmet dental needs and barriers to care for children with significant special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33:29-36. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Berry-Kravis E. Mechanism-based treatments in neurodevelopmental disorders: fragile X syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;50:297-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jaber MA. Dental caries experience, oral health status and treatment needs of dental patients with autism. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:212-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sasaki R, Uchiyama H, Okamoto T, Fukada K, Ogiuchi H, Ando T. A toothbrush impalement injury of the floor of mouth in autism child. Dent Traumatol. 2013;29:467-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Bartolomé-Villar B, Mourelle-Martínez MR, Diéguez-Pérez M, de Nova-García MJ. Incidence of oral health in paediatric patients with disabilities: Sensory disorders and autism spectrum disorder. Systematic review II. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8:e344-e351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bassoukou IH, Nicolau J, Dos Santos MT. Saliva flow rate, buffer capacity, and Ph of autistic individuals. Clin Oral Invest. 2009;13:23-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | DeMattei R, Cuvo A, Maurizio S. Oral assessment of children with an autism spectrum disorder. J Dent Hyg. 2007;81:65. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Vishnu Rekha C, Arangannal P, Shahed H. Oral health status of children with autistic disorder in Chennai. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2012;13:126-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Loo CY, Graham RM, Hughes CV. Behaviour guidance in dental treatment of patients with autism spectrum disorder. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2009;19:390-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Messieha Z. Risks of general anesthesia for the special needs dental patient. Spec Care Dentist. 2009;29:21-25; quiz 67-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Nelson D, Amplo K. Care of the autistic patient in the perioperative area. AORN J. 2009;89:391-392; 395-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Rada RE. Treatment needs and adverse events related to dental treatment under general anesthesia for individuals with autism. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;51:246-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Marshall J, Sheller B, Mancl L, Williams BJ. Parental attitudes regarding behavior guidance of dental patients with autism. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:400-407. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Capp PL, de Faria ME, Siqueira SR, Cillo MT, Prado EG, de Siqueira JT. Special care dentistry: Midazolam conscious sedation for patients with neurological diseases. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2010;11:162-164. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Ferreira X, Oliveira G. [Autism and Early Neurodevelopmental Milestones]. Acta Med Port. 2016;29:168-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Chandrashekhar S, S Bommangoudar J. Management of Autistic Patients in Dental Office: A Clinical Update. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2018;11:219-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P- Reviewer: Murray PE, Vieyra JP S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yin SY