Published online Jul 28, 2015. doi: 10.5320/wjr.v5.i2.176

Peer-review started: September 26, 2014

First decision: December 17, 2014

Revised: April 18, 2015

Accepted: April 28, 2015

Article in press: April 30, 2015

Published online: July 28, 2015

Processing time: 313 Days and 7.5 Hours

Thymic carcinomas are rare tumors of the thymus arising in the thymic epithelium. They represent less than 1% of thymic malignancies. They often present with an advanced disease and metastasize to regional lymph nodes and distant sites. They have a worse prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of 30%-50%, while thymomas are much less invasive and have a 5-year survival of approximately 78%. We report a rare form of clinical presentation of a thymic carcinoma in which the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis was the cornerstone of the diagnosis of cancer. Surgery is considered the salvage treatment when possible. Radiotherapy is a second choice of salvage treatment, when possible depending on its localization and relation to nearby structures such as vascular structures. Molecular target therapy is a more directed, more expensive but less toxic treatment. Further studies need to be carried out for its approval worldwide, outside clinical trials.

Core tip: We report a rare form of clinical presentation of a thymic carcinoma in which the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis was the cornerstone of the diagnosis of cancer. Surgery is considered the salvage treatment when possible. Radiotherapy is a second choice of salvage treatment, when possible depending on its localization and relation to nearby structures such as vascular structures. The prognosis is very reserved, when neither surgery nor radiotherapy can be accomplished. Having an unfavorable molecular signature, less than 10% of thymic carcinomas have c-kit mutations, and clinical outcome of these patients is detrimental.

- Citation: de Macedo JE, Lopes S, Gouveia H, Oliveira S, Cunha J, Faria AL, Rego S, Oliveira A, Krug L, Bravo EM. Myasthenia gravis as a form of clinical presentation of thymic carcinoma. World J Respirol 2015; 5(2): 176-179

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6255/full/v5/i2/176.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5320/wjr.v5.i2.176

Thymic epithelial neoplasms are rare, but are nowadays well-classified according to the Masaoka-Koga system which is the currently most widely used classification[1]. Thymic epithelial neoplasmas comprise thymomas, thymic carcinomas and thymic neuroendocrine tumors. Thymoma is the most common epithelial tumor in the anterior mediastinum in adults. Thymic carcinomas represent less than 1% of all thymic malignancies[2]. They have a worse prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of 30%-50%, while thymomas are much less invasive and have a 5-year survival of approximately 78%[2]. Treatment of thymic carcinomas may vary from complete surgical resection, being the gold standard, to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. The main aim of this case report is to share experience in dealing with the optimal treatment of a rare, indolent and malignant thymic carcinoma, where molecular pathways of thymic carcinomas are still on the verge of a new form of knowledge management.

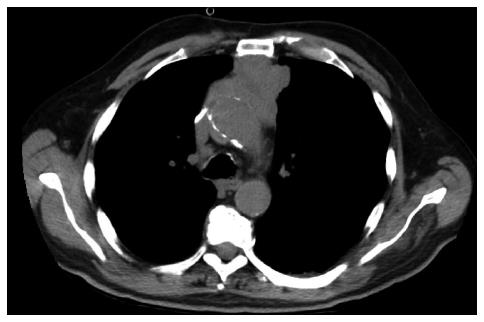

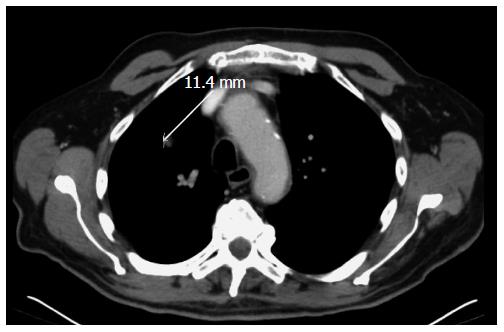

A 76-year-old white man with previously known ischemic heart disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (with domiciliary continuous positive airway pressure), complained of cervical pain, sore throat, dysphagia and mild dyspnea over the past 2 wk. Due to sudden clinical deterioration he was evaluated in the emergency department. The cervical-thoracic-abdominal scan showed an anterior mediastinal mass measuring 66 mm × 60 mm in diameter, a slight pericardial effusion and a 14-mm pulmonary nodule in the right superior lobe (Figures 1 and 2).

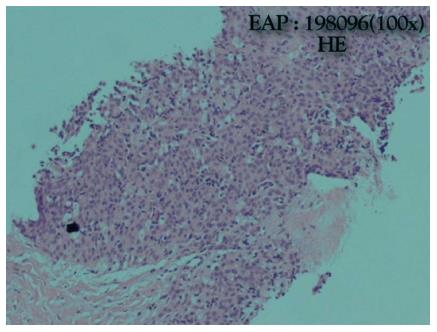

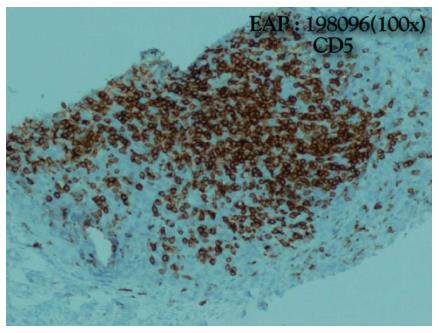

He was admitted to the Internal Medicine Department and started oxazepam. On the same day, he had a sudden worsening of conscious level and global respiratory insufficiency and was submitted to mechanical ventilation. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit. The suspicion of myasthenic syndrome was confirmed by positivity to anticholinesterase antibodies. Two weeks later the patient improved and was extubated to spontaneous ventilation. An anterior mediastinal biopsy was performed and revealed a thymic carcinoma with squamous differentiation, which was poorly differentiated, positive for CD5 and negative for CD 117 and chromogranin. Thus, a type C (World Health Organization) stage IVB (Masaoka-Koga staging) (Figures 3 and 4) thymic carcinoma was diagnosed[1]. The laboratory testing revealed no abnormal values. The patient was transferred to the Internal Medicine Department, clinically improved and was discharged one week later.

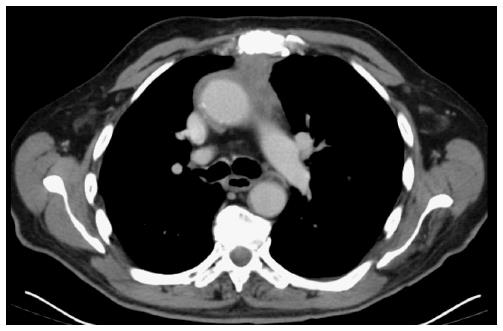

The patient was evaluated by a multidisciplinary team and was diagnosed with a stage IVB disease (isolated pulmonary metastasis). Surgical hypothesis was rejected upfront given the vascular invasion of the tumor and highly suspected pulmonary metastasis. He started chemotherapy with carboplatin (area under the curve 6; D1) and paclitaxel (225 mg/m2 D1) every 3 wk. The patient completed the 4th cycle of chemotherapy with good tolerance and with a significant response on the computed tomography (CT) scan (Figures 5 and 6). No other secondary lesions were observed.

At this time he was evaluated by cardiothoracic surgery and due to his excellent response to chemotherapy, he was proposed for two more cycles and subsequent CT scan and PET-CT evaluation. Concerning a 76-year-old fit patient, surgery shall be considered at a later stage followed by postoperative radiotherapy if indicated.

Thymic carcinomas are aggressive tumors which often metastasize to distant sites. In the case, the high suspicion of myasthenia syndrome was confirmed and associated to thymic carcinoma (30%-50% cases)[3]. Total thymectomy and complete surgical excision are the gold standard of treatments and cisplatin-based chemotherapy is recommended in locally advanced, unresectable and metastatic setting.

Due to recent advances in technologies a better understanding of the molecular behavior of these tumors has been accomplished. Thymic carcinomas have a high frequency of KIT expression (73%-86%), but the rate of kit mutations remains low at 7%-9%[4]. Target therapies (imatinib or sunitinib) may be useful for patients with c-kit mutations besides its low expression[4]. Further molecular profiling for selecting the specific target therapy, is of upmost importance for defining the molecular signature of these tumors. Tumor characterization by clinical, imagiological and histological means are essential, but molecular profiling will allow us to treat our patients more efficiently, with better quality of life and lower toxicity profile.

Tumor stage, complete surgical resection and histology are the main prognostic factors of thymic carcinomas. Nevertheless, a very reserved prognosis when neither surgery nor radiotherapy can be accomplished is considered, but only 60% of the patients die from tumor progression. Other causes of death are autoimmune diseases and other non-malignant related disorders. Having an unfavorable molecular signature, less than 10% of thymic carcinomas have c-kit mutations, and clinical outcome of these patients is detrimental. Despite lacking data on second-line chemotherapy, it remains an option for these patients who present themselves with a recurring disease, with no indication for alternative therapies, namely molecular, surgical or even radiotherapy.

A 76-year-old man complained of cervical pain, sore throat, dysphagia and mild dyspnea over the past 2 wk.

Rapid clinical deterioration.

Other etiologies of anterior mediastinal masses.

An anterior mediastina biopsy was performed.

The cervical-thoracic-abdominal scan showed an anterior mediastinal mass measuring 66 mm × 60 mm in diameter.

A thymic carcinoma with squamous differentiation, which was poorly differentiated, positive for CD5 and negative for CD 117 and chromogranin. A type C (World Health Organization) stage IVB (Masaoka-Koga staging) thymic carcinoma was diagnosed.

Chemotherapy with carboplatin (area under the curve 6; D1) and paclitaxel (225 mg/m2 D1) every 3 wk.

Thymic carcinomas have a high frequency of KIT expression (73%-86%), but the rate of kit mutations remains low at 7%-9%. Target therapies (imatinib or sunitinib) may be useful for patients with c-kit mutations.

Further molecular profiling for selecting the specific target therapy, is of upmost importance for defining the molecular signature of these tumors.

Tumor characterization by clinical, imagiological and histological means is still vital, but molecular profiling will allow us to treat our patients more efficiently, with better quality of life and lower toxicity profile.

The paper is a report of a clinical case about thymic carcinoma that presented with signs and symptoms of a myasthenia gravis.

| 1. | Eng TY, Fuller CD, Jagirdar J, Bains Y, Thomas CR. Thymic carcinoma: state of the art review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:654-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Detterbeck FC, Nicholson AG, Kondo K, Van Schil P, Moran C. The Masaoka-Koga stage classification for thymic malignancies: clarification and definition of terms. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:S1710-S1716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ettinger DS, Riely GJ, Akerley W, Borghaei H, Chang AC, Cheney RT, Chirieac LR, D’Amico TA, Demmy TL, Govindan R. Thymomas and thymic carcinomas: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:562-576. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kelly RJ. Systemic Treatment of advanced Thymic Malignancies. ASCO Educational Book, 2014. Available from: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/11400367-144. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Araujo AMF S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH