Peer-review started: September 16, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: November 26, 2014

Accepted: December 3, 2014

Article in press: December 10, 2014

Published online: February 2, 2015

Processing time: 126 Days and 7.9 Hours

Numerous manuscripts have described dermatologic conditions commonly seen in swimmers. This review provides an update on water dermatoses and discusses newly described conditions such as allergic contact dermatitis to chemical ingredients like potassium peroxymonosulate in pool water. In order to organize water related skin conditions, we have divided the skin conditions into a number of categories. The categories described include infectious and organism-related dermatoses, irritant and allergic dermatoses, and sun-induced dermatoses. The vast majority of skin conditions involving the water athlete result from chemicals and bacteria in the differing aquatic environments. When considering the effects of swimming on the skin, it is also useful to differentiate between exposure to freshwater (lakes, ponds and swimming pools) and exposure to saltwater. The risk of melanoma amongst swimmers is increased, and the use of SPF 30 or greater sunscreen and protective clothing is highly recommended. Swimmers should be reminded to generously apply sunscreen and be instructed on proper sunscreen usage. This review will serve as a guide for dermatologists, athletes, coaches, and other medical professionals in recognition and treatment of these conditions. We also intend for this review to provide dermatologist with a basic framework for the diagnosis and treatment of a few rarely described dermatological conditions in swimmers.

Core tip: Athletes who spend a significant amount of time in the water are subject to a wide array of diseases that include bacterial and fungal infections. These athletes are often exposed to undesirable environments with excessive humidity, heat, cold, wind, and sunlight. These factors may aggravate or cause different skin conditions that require a dermatologist who has specific knowledge of rare aquatic dermatoses.

- Citation: Blattner CM, Kazlouskaya V, Coman GC, Blickenstaff NR, Murase JE. Dermatological conditions of aquatic athletes. World J Dermatol 2015; 4(1): 8-15

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6190/full/v4/i1/8.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5314/wjd.v4.i1.8

Excessive dryness (swimmer’s xerosis) is one of the most common conditions seen in water athletes. It is caused by sebum dilution with water, osmotic effect, and stripping off the stratum corneum. Taking long showers with scrubs and soaps after activity also precipitates the problem. Although easy to diagnose, swimmer’s xerosis should be differentiated from swimmer’s itch and urticaria[1-5]. Preventative measures include decreasing shower duration and applying ointment based moisturizing preparations before and after pool activities[4].

Aquagenic acne occurs due to the rebound effect of sebum over-production after continuously washing off the oils from the skin surface. It may present as an acute exacerbation of a preexisting condition or as a new onset disorder. Other mechanisms include the effect of chlorinated compounds in pool water, occlusion of the sebaceous glands by denuded epidermis, and use of comedogenic moisturizing creams and sunscreens. Aquagenic acne typically presents as common acne and should be treated accordingly. Topical or systemic agents can be used depending on level of severity, but it should be noted that some topical agents may cause additional irritation. Specifically, isotretinoin, commonly used for severe acne treatment, may interfere with performance and cause neuromuscular symptoms and myalgias[6,7].

Some evidence suggests that swimmers may be more prone to allergic reaction than non-swimmers since swimmers have a higher incidence of positive skin prick tests, asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitus, and bronchial hyperactivity[8-12]. Increased allergy rates may be partly explained by the use of chlorinated or brominated disinfectants in swimming pools that may increase sensitization to other allergens[13].

Disinfectants may cause allergic contact dermatitis (‘‘pool water dermatitis”). Compounds proven to cause pool water dermatitis include gaseous chlorine, sodium and lithium hypochloride, 1-bromo-3-chloro-5,5-dimethylhydantoin (BCDMH), potassium peroxymonosulfate, and aluminum chlorohydrate[14-17]. Brominated compounds were previously thought to provide an alternative to chlorine, but have shown an increased potential to cause irritant contact dermatitis. BCDMH is a component that slowly releases bromium and chlorine and is believed to be the causative agent of an outbreak of swimming pool contact dermatitis in the United Kingdom[18-20]. Initially, only negative patch tests to BCDMH were seen, and it was believed to be a solely irritant dermatitis. However, positive patch tests for BCDMH were later reported[16]. It was also proposed that certain individuals may develop an allergic contact dermatitis because of the chlorium, released from BCDMN, but test were negative for BCDMH itself[21].

Allergic contact dermatitis can also be caused by certain clothing and equipment swimmers use (Figure 1). Early reports described reactions to the components of resins (thioureas, benzothiazole, dithiocarbamate and formaldehyde) in goggles, scuba masks, nose clips, earplugs, fins, fin straps, and swimsuits[22-29]. Allergic contact dermatitis to dodecyl diaminoethyl glycine, a diving suit disinfectant, has also been described[30]. Raccoon-like depigmentation was described from use of neoprene goggles in a child, but the etiology (toxic or allergic) was not confirmed[31].

Irritant contact dermatitis in athletes usually develops as a result of chronic friction (Figure 2). Use of caps and goggles that press tightly against the skin may lead to purpura formation[4]. A specific irritant dermatitis known as “pool toes” and “pool palms” is caused by friction of the feet and palms against the pool’s rough cement bottom[32-34]. Another form of irritant dermatitis in males is “shoulder dermatitis”, which is caused by rubbing an unshaven chin against the shoulder while performing the crawl stroke[35]. In surfers, nodules may develop in the pretibial area due to continuous friction with the surf board[35]. These irritant dermatoses usually resolve spontaneously with cessation of the offending activity, but persistent nodules can be treated with topical keratolytics and intralesional corticosteroids.

Athletes who spend a significant amount of time in the water are subject to a wide array of bacterial and fungal infections. Excessive maceration, dryness, and changes in the skin microflora contribute to the development of the skin infections. Additionally, the risk of disease is increasing because of pool overcrowding and common use of showers and towels.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is able to survive in high temperate water and causes several skin conditions including hot tube folliculitis, otitis externa, and hot foot syndrome. Outbreaks of Pseudomonal infections may arise from contact with contaminated water[36-38]. Current studies show that Pseudomonas contamination is common in pools and even more so in hot tubs since they are difficult to clean[39]. To decrease the rate of infection, chloride concentration of the water should be monitored daily. Athletes, especially those who train intensely for a prolong period of time, are prone to the colonization of the ear canal by Pseudomonas[40].

Hot tub folliculitis presents as a disseminated itchy pustular rash that appears within two days of water exposure. It is prone to localize in the intertriginous areas and may also be seen in a bathing suit distribution. Hot tub folliculitis (Figure 3) is usually a self-limited condition, but systemic symptoms such as low-grade fever, lymphadenopathy, headache and malaise may be rarely seen. It can also be accompanied by other Pseudomonal infections including otitis, conjunctivitis, mastitis, and urinary tract infections[41]. Pseudomonas folliculitis may also develop under the suit that has led to the aptly suited description of “diving suit folliculitits”[42,43].

Pseudomonas is the most frequently implicated pathogen in the development of otitis externa. Swimmers are five times more likely to develop otitis externa than non-swimmers[44]. Otitis externa presents with pain limited to the external auditory canal, but the ear appears erythematous and swollen with variable discharge (Figure 4). Prophylaxis is generally achieved through proper cleaning and drying of the ear canal in addition to avoidance of excessive moisture in and around the canal. Acidification with a topical solution of 2% acetic acid combined with hydrocortisone for inflammation is effective treatment, although most physicians will also prescribe combination steroid/antibiotic drops. Another dermatoses known as hot foot syndrome has been described as a subcutaneous eruption on the soles of children swimming in the same pool[38,45]. In both reports Pseudomonas was isolated from the swimming pool, but a causative relationship (isolation from the skin lesion) was only performed in one child, leaving debates about the etiology of the condition[46,47].

Swimmers also show increased rates of skin coloniza-tion by Staphylococcus and Streptococcus[40]. Bikini bottom is a deep folliculitis of the buttocks that is caused by Streptococcus or Staphylococcus aureus. It is the result of wearing tight fitting bikinis for prolonged periods of time and presents as firm nodules that manifest along the inferior gluteal crease[48]. Prevention is aimed at early removal of the swimsuit, while treatment consists of oral antibiotics based on sensitivities.

Recent European and American studies have shown that most swimming pools and showers are contaminated with Mycobacteria[49-52]. Although not necessarily sympto-matic, these bacteria can cause granulomatous disease of the lungs and skin[53]. Mycobacterium marinum (M. marinum) is ubiquitous in pools, aquariums, freshwater, and saltwater. Since its discovery in Sweden, multiple outbreaks of M. marinum outbreaks have been described throughout the world[54-56]. It also causes so-called “fish tank” or “swimming pool” granuloma which has a predilection for the dorsum of the hands, fingers, and elbows, especially when skin trauma or open wounds are present[57]. The predilection for the extremities is due to inhibition of growth of M. marinum at 37 °C so the organisms tends to infect the cooler parts of the body including the extremities[57]. The granuloma usually presents as a solitary, erythematous papule or nodule and may be mistaken for sporotrichosis or leishmaniasis[58,59]. Disseminated infection is rare, although a case of disseminated Mycobacterium that presented as erythema nodosum was previously described in a 12-year-old girl[60]. Histopathology of skin lesions reveal typical tuberculoid granulomas in only 60% of cases, while the other 40% display non-specific inflammation with neutrophils[61]. Frequently, superficial biopsies fail to show specific changes, but granulomas may be seen in the subcutaneous tissue or synovium. Paucity of microorganisms is the characteristic feature of M. marinum infections, and the identification of the microorganism is a challenge. Culture and polymerase chain reactions may also be useful for identifying microorganisms[62,63]. Localized lesions of swimming pool granuloma are self-limited and resolve with scar formation. Patients can be treated with clarithromycin, minocycline and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; multidrug therapy with ethambutol and rifampin is needed if disseminated disease is present[57]. Although rare in immunocompetent individuals, other mycobacteria, mainly M. cheloneae and M. fortuitum may also cause cutaneous granulomas.

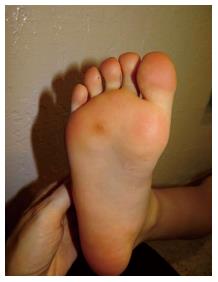

Several studies have shown that swimming pools are contaminated with dermatophytes, which increases the risk of infection[64]. Prolonged contact with water causes increased susceptibility to fungal infections, and Kamihama et al[65] found that 63.6% of swimmers are dermatophyte carriers. However, the incidence of tinea pedis among aquatic athletes is not well studied, but early reports have found that it may be up to 10%[52,66]. Trichophyton mentagrophytes accounts for up to 85% of infections and has been isolated from swimming pool decks and locker room floors[65,66]. Tinea pedis (Figure 5) should be differentiated from pitted keratolysis, caused by Corynebacteria, which presents with the small punched-out depressions and an unpleasant smell. Tinea can be prevented by proper foot hygiene and patient education. Initial treatment involves topical antifungals twice daily for one to two months, but systemic antifungal agents may be used if refractory disease is present.

Swimmers and those who use common showers have a greater incidence of plantar warts (Figure 6) and molluscum contagiosum, although the exact incidence in athletes is unknown[67-69]. Liquid nitrogen, curettage, and salicylic acid are helpful for removal of the lesion. There is not enough evidence to confirm that covering warts helps prevent spread[70].

Aquatic athletes are prone to develop specific hair conditions. Green hair discoloration, often seen in light-haired athletes, is an effect of bleach and copper ion deposition that are used to kill algae[71]. Seborrheic keratosis may also undergo green color change along with the hair due to copper ion deposition[72]. Wetting the hair prior to chlorinated water exposure, prompt bathing after exposure, and use of a copper chelating shampoo may mitigate this problem. Hair discoloration coexisting with nail plate damage has also been described in Japanese swimmers and was considered to be a result of cuticle damage due to water friction and hypochlorus acid penetration[73].

Athletes who swim in marine water may be exposed to conditions transmitted by sea and river microorganisms. Jellyfish, anemones, sponges, corals and rarely Coelenterates (Cnidaria) are known to cause dermatitis and infection if traumatized (Figure 7). Dermatitis can also develop after contact with fish (jellyfish, stingray, weeverfish, stonefish), cones, or sea snakes (Hydrophiidae) due to their venomous toxin (Figure 8). Exposure may result in blistering and skin necrosis along with systemic symptoms, including respiratory muscle paralysis.

Another dermatitis, known as “seabather’s eruption”, is a pruritic eruption that appears under the bathing suit. It is caused by contact with swimming stages of the thimble jellyfish, Linuche unguiculata, and it is seen in Florida, the Caribbean and Brazil. Cercarial dermatitis (swimmers’ itch) develops after penetration of Shistosoma’s larvae through human skin. The exact species of Shistosomas that cause the eruption, their animal hosts, and distribution is still under investigation[74]. The condition is usually self-limited and presents as pruritic papules on exposed body surface areas, usually sparing the bathing suit region.

Onchocerciasis (river blindness) is caused by the filaria Onchocerca volvulus. Acquisition of the disease may occur after swimming in the Middle East, Africa or Latin America. Skin changes in onchocerciasis include nodule formation in the area of penetration, a pruritic rash, lichenification, vitiligo-like changes, and atrophy after microfillaria migration. Early detection and treatment of filaria with ivermectin helps prevent river blindness.

Outdoor athletes are often exposed to undesirable environ-mental conditions such as excessive humidity, heat, cold, wind, and sunlight that may aggravate or cause different skin conditions. Sun exposure in athletes may be extreme and can lead to a higher risk of basal cell carcinoma (Figure 9), squamous cell carcinoma (Figures 10 and 11), and melanoma (Figure 12). Moehrle[75] has found that burns were seen in triathletes despite of use of SPF 25+ sunscreens. However, data regarding the incidence of skin cancers in aquatic athletes is limited to several early studies. In 1992, a screening of surfers demonstrated an increased incidence of basal cell carcinomas in surfers, despite of their young age[76]. Nelemans et al[77] have shown that the odds of melanoma risk were higher in swimmers, but he contributed it largely to the chlorination of the water in swimming pools.

Use of SPF 30 or greater sunscreen and protective clothing is highly recommended to athletes[78,79]. When counseling swimmers on sunscreen usage, one should advise use of a sunscreen that contains SPF 30 or greater, is water resistant, and provides broad spectrum UVA and UVB coverage. Swimmers should also be told to generously apply the sunscreen to all bare skin before going outdoors since it can take up to 15 min for skin to absorb sunscreen. Finally, they must be counseled to reapply sunscreen immediately after swimming or every two hours, whichever is sooner.

Aquatic athletes present a unique set of challenges for the dermatologist. It is important to educate athletes, parents, and coaches in an attempt to prevent short and long term dermatological sequela.

| 1. | Tlougan BE, Podjasek JO, Adams BB. Aquatic sports dermatoses: part 1. In the water: freshwater dermatoses. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:874-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tlougan BE, Podjasek JO, Adams BB. Aquatic sports dermatoses: Part 3. On the water. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1111-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tlougan BE, Podjasek JO, Adams BB. Aquatic sports dematoses. Part 2 - in the water: saltwater dermatoses. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:994-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Basler RS, Basler GC, Palmer AH, Garcia MA. Special skin symptoms seen in swimmers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:299-305. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Adams BB. Priritus and urticaria. Springer New York: Sports Dermatology 2006; 180-181. |

| 6. | Chroni E, Monastirli A, Tsambaos D. Neuromuscular adverse effects associated with systemic retinoid dermatotherapy: monitoring and treatment algorithm for clinicians. Drug Saf. 2010;33:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Heudes AM, Laroche L. Muscular damage during isotretinoin treatment. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1998;125:94-97. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Zwick H, Popp W, Budik G, Wanke T, Rauscher H. Increased sensitization to aeroallergens in competitive swimmers. Lung. 1990;168:111-115. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Silvestri M, Crimi E, Oliva S, Senarega D, Tosca MA, Rossi GA, Brusasco V. Pulmonary function and airway responsiveness in young competitive swimmers. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48:74-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Langdeau JB, Turcotte H, Bowie DM, Jobin J, Desgagné P, Boulet LP. Airway hyperresponsiveness in elite athletes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1479-1484. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Katelaris CH, Carrozzi FM, Burke TV, Byth K. Patterns of allergic reactivity and disease in Olympic athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:401-405. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Bougault V, Boulet LP. Airways disorders and the swimming pool. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2013;33:395-408, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Voisin C, Sardella A, Bernard A. Risks of new-onset allergic sensitization and airway inflammation after early age swimming in chlorinated pools. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2014;217:38-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pardo A, Nevo K, Vigiser D, Lazarov A. The effect of physical and chemical properties of swimming pool water and its close environment on the development of contact dermatitis in hydrotherapists. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50:122-126. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Salvaggio HL, Scheman AJ, Chamlin SL. Shock treatment: swimming pool contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:494-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dalmau G, Martínez-Escala ME, Gázquez V, Pujol-Montcusí JA, Canadell L, Espona Quer M, Pujol RM, Vilaplana J, Gaig P, Giménez-Arnau A. Swimming pool contact dermatitis caused by 1-bromo-3-chloro-5,5-dimethyl hydantoin. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:335-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stenveld H. Allergic to pool water. Saf Health Work. 2012;3:101-103. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Rycroft RJ, Penny PT. Dermatoses associated with brominated swimming pools. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:462. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Dermatoses associated with brominated swimming pools. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:913. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kelsall HL, Sim MR. Skin irritation in users of brominated pools. Int J Environ Health Res. 2001;11:29-40. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Sasseville D, Geoffrion G, Lowry RN. Allergic contact dermatitis from chlorinated swimming pool water. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:347-348. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Romaguera C, Grimalt F, Vilaplana J. Contact dermatitis from swimming goggles. Contact Dermatitis. 1988;18:178-179. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Alomar A, Vilaltella I. Contact dermatitis to dibutylthiourea in swimming goggles. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:348-349. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Boehncke WH, Wessmann D, Zollner TM, Hensel O. Allergic contact dermatitis from diphenylthiourea in a wet suit. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;36:271. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Balestrero S, Cozzani E, Ghigliotti G, Guarrera M. Allergic contact dermititis from a wet suit. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:228-229. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Bergendorff O, Hansson C. Contact dermatitis to a rubber allergen with both dithiocarbamate and benzothiazole structure. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:278-280. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Nagashima C, Tomitaka-Yagami A, Matsunaga K. Contact dermatitis due to para-tertiary-butylphenol-formaldehyde resin in a wetsuit. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:267-268. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Vaswani SK, Collins DD, Pass CJ. Severe allergic contact eyelid dermatitis caused by swimming goggles. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:672-673. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Seyfarth F, Krautheim A, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Sensitization to para-amino compounds in swim fins in a 10-year-old boy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:770-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Munro CS, Shields TG, Lawrence CM. Contact allergy to Tego 103G disinfectant in a deep-sea diver. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;21:278-279. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Goette DK. Raccoon-like periorbital leukoderma from contact with swim goggles. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;10:129-131. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Cohen PR. Pool toes: a sports-related dermatosis of swimmers. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:794-795. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Wong LC, Rogers M. Pool palms. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:95. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Lacour JP. Juvenile palmar dermatitis acquired at swimming pools. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1995;122:695-696. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Koehn GG. Skin injuries in sports medicine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:152. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pseudomonas dermatitis/folliculitis associated with pools and hot tubs--Colorado and Maine, 1999-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:1087-1091. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, Dunne WM, Bayliss SJ. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Fiorillo L, Zucker M, Sawyer D, Lin AN. The pseudomonas hot-foot syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:335-338. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Lutz JK, Lee J. Prevalence and antimicrobial-resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in swimming pools and hot tubs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:554-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Gräf W, Hilmer W, von Eichhorn U. Microbial colonization of the nasopharynx, external auditory canal, hair of the head and armpit in high performance swimmers. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg B. 1983;177:156-169. [PubMed] |

| 41. | George SM, Rattan J, Walker K, Garg A. Pseudomonas mastitis caused by hot tub exposure. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Lacour JP, el Baze P, Castanet J, Dubois D, Poudenx M, Ortonne JP. Diving suit dermatitis caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:1055-1056. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Saltzer KR, Schutzer PJ, Weinberg JM, Tangoren IA, Spiers EM. Diving suit dermatitis: a manifestation of Pseudomonas folliculitis. Cutis. 1997;59:245-246. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Hoadley AW, Knight DE. External otitis among swimmers and nonswimmers. Arch Environ Health. 1975;30:445-448. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Michl RK, Rusche T, Grimm S, Limpert E, Beck JF, Dost A. Outbreak of hot-foot syndrome - caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Klin Padiatr. 2012;224:252-255. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Zvulunov A, Trattner A, Naimer S. Pseudomonas hot-foot syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1643-1644. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Hot-foot syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:iii-iiv. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Basler RS, Basler DL, Basler GC, Garcia MA. Cutaneous injuries in women athletes. Dermatol Nurs. 1998;10:9-18; quiz 19-20. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Iivanainen E, Northrup J, Arbeit RD, Ristola M, Katila ML, von Reyn CF. Isolation of mycobacteria from indoor swimming pools in Finland. APMIS. 1999;107:193-200. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Leoni E, Legnani P, Mucci MT, Pirani R. Prevalence of mycobacteria in a swimming pool environment. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87:683-688. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Havelaar AH, Berwald LG, Groothuis DG, Baas JG. Mycobacteria in semi-public swimming-pools and whirlpools. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg B. 1985;180:505-514. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Glazer CS, Martyny JW, Lee B, Sanchez TL, Sells TM, Newman LS, Murphy J, Heifets L, Rose CS. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in aerosol droplets and bulk water samples from therapy pools and hot tubs. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2007;4:831-840. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Sood A, Sreedhar R, Kulkarni P, Nawoor AR. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis-like granulomatous lung disease with nontuberculous mycobacteria from exposure to hot water aerosols. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:262-266. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Linell F, Norden A. Mycobacterium balnei, a new acid-fast bacillus occurring in swimming pools and capable of producing skin lesions in humans. Acta Tuberc Scand Suppl. 1954;33:1-84. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Leuenberger R, Bodmer T. [Clinical presentation and therapy of Mycobacterium marinum infection as seen in 12 cases]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2000;125:7-10. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Mollohan CS, Romer MS. Public health significance of swimming pool granuloma. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1961;51:883-891. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Philpott JA, Woodburne AR, Philpott OS, Schaefer WB, Mollohan CS. Swimming pool granuloma. a study of 290 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:158-162. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Tigges F, Bauer A, Hochauf K, Meurer M. Sporotrichoid atypical cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium marinum. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2009;18:31-34. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Mutasim DF. Re: AlKhodair R, Al-Khenaizan S. Fish tank granuloma: misdiagnosed as cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol 2010, 49: 53-55. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:120; author reply 120-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Garty B. Swimming pool granuloma associated with erythema nodosum. Cutis. 1991;47:314-316. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Cribier B, Aubry A, Caumes E, Cambau E, Jarlier V, Chosidow O. Histopathological study of Mycobacterium marinum infection. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Cai L, Zhang JZ. Detection and identification of Mycobacteria with polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) from patients with Mycobacterial skin infections. Beijing Daxue Xuebao. 2004;36:462-465. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Cai L, Chen X, Zhao T, Ding BC, Zhang JZ. Identification of Mycobacterium marinum 65 kD heat shock protein gene by polymerase chain reaction restriction analysis from lesions of swimming pool granuloma. Chin Med J (Engl). 2006;119:43-48. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Maghazy SM, Abdel-Mallek AY, Bagy MM. Fungi in two swimming pools in Assiut town, Egypt. Zentralbl Mikrobiol. 1989;144:213-216. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Kamihama T, Kimura T, Hosokawa JI, Ueji M, Takase T, Tagami K. Tinea pedis outbreak in swimming pools in Japan. Public Health. 1997;111:249-253. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Attye A, Auger P, Joly J. Incidence of occult athlete’s foot in swimmers. Eur J Epidemiol. 1990;6:244-247. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Choong KY, Roberts LJ. Molluscum contagiosum, swimming and bathing: a clinical analysis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:89-92. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Johnson LW. Communal showers and the risk of plantar warts. J Fam Pract. 1995;40:136-138. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Niizeki K, Kano O, Kondo Y. An epidemic study of molluscum contagiosum. Relationship to swimming. Dermatologica. 1984;169:197-198. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Vaile L, Finlay F, Sharma S. Should verrucas be covered while swimming? Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:236-237. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Biel K, Kretzschmar L, Müller C, Metze D, Traupe H. [Green hair caused by frequent swimming pool use]. Hautarzt. 1997;48:568-571. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Peterson J, Shook BA, Wells MJ, Rodriguez M. Cupric keratosis: green seborrheic keratoses secondary to external copper exposure. Cutis. 2006;77:39-41. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Nanko H, Mutoh Y, Atsumi R, Kobayashi Y, Ikeda M, Yoshikawa N, Fukuda S, Kawa Y, Mizoguchi M. Hair-discoloration of Japanese elite swimmers. J Dermatol. 2000;27:625-634. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Brant SV, Loker ES. Discovery-based studies of schistosome diversity stimulate new hypotheses about parasite biology. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:449-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Moehrle M. Ultraviolet exposure in the Ironman triathlon. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1385-1386. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Dozier S, Wagner RF, Black SA, Terracina J. Beachfront screening for skin cancer in Texas Gulf coast surfers. South Med J. 1997;90:55-58. [PubMed] |

| 77. | Nelemans PJ, Rampen FH, Groenendal H, Kiemeney LA, Ruiter DJ, Verbeek AL. Swimming and the risk of cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma Res. 1994;4:281-286. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Wysong A, Gladstone H, Kim D, Lingala B, Copeland J, Tang JY. Sunscreen use in NCAA collegiate athletes: identifying targets for intervention and barriers to use. Prev Med. 2012;55:493-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Ellis RM, Mohr MR, Indika SH, Salkey KS. Sunscreen use in student athletes: a survey study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:159-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Chong WS, Hu SCS S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL