Published online Dec 18, 2018. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i12.292

Peer-review started: August 22, 2018

First decision: October 4, 2018

Revised: October 16, 2018

Accepted: November 15, 2018

Article in press: November 15, 2018

Published online: December 18, 2018

Processing time: 118 Days and 14.8 Hours

To examine humeral retroversion in infants who sustained brachial plexus birth palsy (BPBI) and suffered from an internal rotation contracture. Additionally, the role of the infraspinatus (IS) and subscapularis (SSc) muscles in the genesis of this bony deformation is explored.

Bilateral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of 35 infants (age range: 2-7 mo old) with BPBI were retrospectively analyzed. Retroversion was measured according to two proximal axes and one distal axis (transepicondylar axis). The proximal axes were: (1) the perpendicular line to the borders of the articular surface (humeral centerline); and (2) the longest diameter through the humeral head. Muscle cross-sectional areas of the IS and SSc muscles were measured on the MRI-slides representing the largest muscle belly. The difference in retroversion was correlated with the ratio of muscle-sizes and passive external rotation measurements.

Retroversion on the involved side was significantly decreased, 1.0° vs 27.6° (1) and 8.5° vs 27.2° (2), (P < 0.01), as compared to the uninvolved side. The size of the SSc and IS muscles on the involved side was significantly decreased, 2.26 cm² vs 2.79 cm² and 1.53 cm² vs 2.19 cm², respectively (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the muscle ratio (SSc/IS) at the involved side was significantly smaller compared to the uninvolved side (P = 0.007).

Even in our youngest patient population, humeral retroversion has a high likelihood of being decreased. Altered humeral retroversion warrants attention as a structural change in any child being evaluated for the treatment of an internal rotation contracture.

Core tip: This study examines humeral retroversion in infants who sustained neonatal brachial plexus palsy and suffered from an internal rotation contracture. The existing common treatment options all strive for better function of the upper extremity through an improved position of the hand in space. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the development of the pathogenesis of this injury is important. We found a significant reduction of humeral retroversion in our study group (mean difference, 26.8). When treatment becomes warranted and contralateral humeral version measurements greatly differ, a humeral derotational osteotomy may offer the best improvement regarding the hand position.

- Citation: van de Bunt F, Pearl ML, van Essen T, van der Sluijs JA. Humeral retroversion and shoulder muscle changes in infants with internal rotation contractures following brachial plexus birth palsy. World J Orthop 2018; 9(12): 292-299

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v9/i12/292.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v9.i12.292

The most common musculoskeletal sequela of neurologic injury of brachial plexus birth palsy (BPBI) is an internal rotation contracture of the shoulder. This contracture is frequently associated with deformity of the glenohumeral joint[1-5]. These bony deformities have been thought to be a consequence of abnormal muscular development[6-8].

The internal rotation contracture secondary to BPBI has been associated with alterations of humeral retroversion[9-12]. Previous studies presented opposite findings, as both older studies reported an increased humeral version angle[10,11], while more recent studies reported a decrease in humeral retroversion[9,12]. Normal humeral retroversion is greatest at birth and gradually decreases through adolescence[13-15] to adult values averaging between 25-30 with well documented individual variation[16]. One well-studied exception is the throwing athlete, for whom retroversion has been shown to be greater on the dominant throwing side, due to repetitive throwing that usually begins in early childhood[17-21].

The existing common treatment options consist of soft tissue procedures (releases and tendon transfers) and bone realignment procedures (rotational osteotomy) with the aim to provide better function of the upper extremity through an improved position of the hand in space[22-26]. This position is directly related to the humeral version angle. We studied humeral retroversion in 35 consecutive infants who were under evaluation for treatment of their internal rotation contractures secondary to unilateral BPBI in this retrospective observational study. Our main goal was to further elucidate the timing that these anatomic changes may occur; therefore, we included our youngest patient population. We hypothesized that the retroversion angle (RV-angle) on the involved side would be significantly decreased relative to the uninvolved side and that the difference would increase with age. Since the subscapularis (SSc) and infraspinatus (IS) muscles, are an agonist-antagonist muscle pair regarding humeral rotation, we hypothesized that an imbalance between these muscles would correlate with altered humeral version.

In this retrospective observational study, we included 37 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) -scans from a consecutive series of infants (< 1 year old) with a unilateral BPBI. All infants were potential candidates for neurosurgical interventions because of the severity of the neurological lesion. This study was IRB approved.

MRI studies were performed on a 1.5-T MRI-unit (Magnetom 1.5 T Vision; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). A FISP three-dimensional pulse acquisition sequence (repetition time, 25 msec; time to echo, 10 msec; flip angle 40°) with ranges from 0.8 to 1.5 mm partitions was used to obtain images from both shoulders and upper arms, representing the full humerus and glenohumeral joint in the axial plane. All children were given pethidine, droperidol and chlorpromazine intramuscularly. During sedation, they were monitored by electrocardiograph, measurement of oxygen saturation, and by video. Children were not moved during the imaging protocol.

From these 37 studies, two were insufficient for completing our detailed measurement protocol, as one study did not capture the entire humerus and motion artifacts compromised the other study.

Our Radiology department anonymized the MRI studies before performing our measurement protocol; Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine files were imported as a numerical database into Osirix (Pixmeo, Geneva, Switzerland). For humeral version measurements, axial plane slides from the involved and uninvolved side that to our best efforts represented the midpoint of the humeral head were selected. For the measurement of muscle dimensions, axial plane slides representing the largest cross-sectional area of the SSc muscle and infraspinatus muscle were selected and exported as TIFF files. The TIFF files were imported into Geometer’s Sketchpad version 5.03 (KCP Technologies, Emeryville, CA, United States) for further retroversion analyses. The region of interest tool available in Osirix was used for muscle cross-sectional area measurements. The Narakas classifications were assigned as described by Narakas[27]. Passive external rotation was measured with the arm in the adducted position and the elbow by the side.

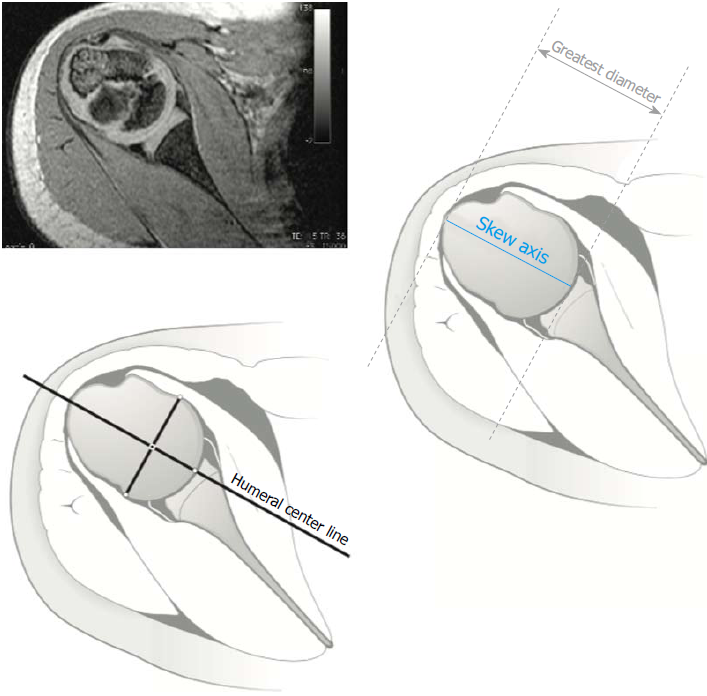

Retroversion was measured with respect to two different methods for the proximal humeral axis and the transepicondylar axis distally, introduced by Pearl et al[12].

The first proximal reference axis was chosen to provide continuity with earlier retroversion analysis performed in this specific patient group[10,11]. This axis is conforming to the longest diameter through the humeral head. A line segment was created, which spanned the greatest distance from the periphery of the greater tuberosity to the medial articular surface and is labeled as the skew axis (SA) (Figure 1)[2].

Retroversion was analyzed using the humeral center-line (HCL) as the proximal axis (Figure 1). This is a commonly used axis in various retroversion studies[19,28-32]. The HCL represents the perpendicular projection from the margins of the articular surface.

Based on the literature, retroversion of the humeral head is shown as a positive value and anteversion is shown as a negative value. Two investigators performed the humeral version measurements.

Cross-sectional areas of the IS and SSc muscles were measured using the closed region-of-interest polygon tool in Osirix (Pixmeo). The MRI slides depicting the largest muscle bellies were identified for measurement of this cross-sectional area. Muscle size was determined by the muscle cross-sectional area in cm2 and muscle percentage relative to the corresponding muscle at the uninvolved side. Furthermore, the ratio of the SSc and IS muscle (SSc/IS) was calculated to compare muscle balance between both sides and correlate these with the ΔRV-angle.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 22.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The distribution analysis showed an approximately normal distribution.

Standard descriptive measures as mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values are reported for retroversion of the involved and uninvolved sides, as for the muscle surface area measurements, and their difference (Δ) within the study population. Pearson product-moment or Spearman rank correlation coefficients are estimated between each of these and passive external rotation and Narakas classification, as appropriate, based on the underlying distribution and type of the data. Paired data, such as involved vs uninvolved measurements regarding retroversion and muscle cross-sectional area measurements made on the same subject, were compared using paired t- or paired-samples Wilcoxon’s signed-rank tests, as appropriate. Inter-rater reliability assessment by Intraclass correlations coefficient (ICC) was performed. A Bland-Altman plot was created to visualize potential differences in retroversion measuring methods[33].

The 35 children included in our study had a mean age of 4.3 mo (range of 2.1-6.5 mo), and they were classified according to the Narakas classification: Narakas I: 18 cases; Narakas II: 4 cases; Narakas III: 15 cases. Internal rotation contractures varied from -45° to 12°, with a mean of -18°, measured as passive external rotation with the elbow by the side (Table 1).

| Subject | Narakas | Age (mo) | External rotation (passive) (°) | Retroversion involved (HCL) (°) | Retroversion involved (SA) (°) | Retroversion uninvolved (HCL) (°) | Retroversion uninvolved (SA) (°) |

| 1 | 3 | 2.6 | -15 | 7.665 | 11.25 | 26.4 | 26.315 |

| 2 | 1 | 3.1 | -5 | -9.16 | 11.045 | 23.18 | 13.485 |

| 3 | 1 | 3.2 | -40 | -17.125 | 4.04 | 18.65 | 17.05 |

| 4 | 3 | 3.2 | -30 | 14.175 | 23.395 | 30.56 | 31.865 |

| 5 | 3 | 3.3 | 0 | -7.05 | 6.67 | 31.23 | 32.85 |

| 6 | 3 | 3.4 | -10 | -24.74 | -19.26 | 41.72 | 31.705 |

| 7 | 3 | 3.4 | 0 | 7.67 | 7.905 | 30.145 | 29.165 |

| 8 | 3 | 3.5 | -20 | 35.595 | 35.015 | 27.295 | 31.23 |

| 9 | 2 | 3.5 | -5 | -10.885 | 1.615 | 24.17 | 23.905 |

| 10 | 1 | 3.5 | -20 | 4.54 | 2.05 | 32.21 | 26.49 |

| 11 | 3 | 3.6 | -20 | 1.99 | 5.695 | 43.55 | 36.11 |

| 12 | 1 | 3.6 | -20 | 3.6 | 22.565 | 54.905 | 47.955 |

| 13 | 3 | 3.8 | -25 | 1.595 | 9.425 | 29.355 | 36.42 |

| 14 | 1 | 4.0 | -5 | -6.715 | 3.44 | 29.115 | 28.165 |

| 15 | 2 | 4.1 | -15 | -13.53 | -1.035 | 21.59 | 25.605 |

| 16 | 1 | 4.1 | -15 | 14.975 | 9.85 | 25.575 | 21.24 |

| 17 | 3 | 4.5 | -25 | 0.065 | -2.075 | 19.47 | 19.995 |

| 18 | 3 | 4.5 | -45 | 24.195 | 20.195 | 34.19 | 34.55 |

| 19 | 1 | 4.5 | -10 | -4.115 | 6.1 | 24.305 | 20.175 |

| 20 | 2 | 4.6 | -30 | -7.205 | 11.675 | 13.465 | 14.06 |

| 21 | 3 | 4.6 | -10 | -3.14 | 7.29 | 15.445 | 12.14 |

| 22 | 1 | 4.7 | -20 | 4.125 | 18.195 | 23.045 | 30.385 |

| 23 | 1 | 4.7 | -20 | -20.83 | 1.9 | 21.85 | 30.085 |

| 24 | 1 | 4.8 | -40 | 4.875 | 9.95 | 15.655 | 20.11 |

| 25 | 3 | 4.9 | -40 | 8.935 | 9.525 | 18.805 | 11.765 |

| 26 | 1 | 5.0 | -15 | 38.24 | 33.53 | 20.055 | 15.945 |

| 27 | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | -8.86 | 4.405 | 24.85 | 21.6 |

| 28 | 1 | 5.0 | -15 | -30.23 | -20.135 | 38.975 | 23.31 |

| 29 | 1 | 5.0 | -10 | 24.725 | 25.535 | 32.98 | 39.03 |

| 30 | 1 | 5.1 | -5 | 8.79 | 10.05 | 20.115 | -2.295 |

| 31 | 1 | 5.4 | -20 | -28.55 | -11.965 | 47.445 | 39.185 |

| 32 | 3 | 5.6 | -35 | 3.385 | 6.45 | 30.395 | 27.485 |

| 33 | 3 | 5.9 | -15 | -16.805 | 11.66 | 18.085 | 14.5 |

| 34 | 2 | 5.9 | -30 | 11.89 | 7.225 | 28.56 | 35.075 |

| 35 | 1 | 6.5 | -10 | 17.315 | 14.43 | 31.08 | 22.5 |

| Mean | 4.3 | -18.3 | 0.8 | 8.5 | 27.7 | 25.4 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.9 | 12 | 16.1 | 11.7 | 9.2 | 9.8 | |

| Minimum | 2.6 | -45 | -30.23 | -20.135 | 13.465 | -2.295 | |

| Maximum | 6.5 | 0 | 38.24 | 35.015 | 54.905 | 47.955 | |

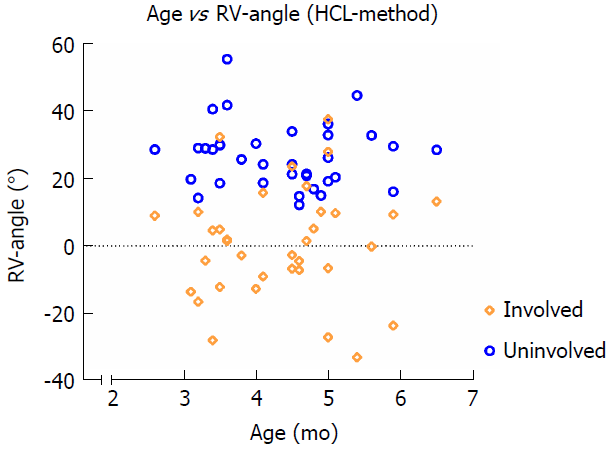

Retroversion measured according to the HCL and the transepicondylar axis was significantly decreased on the involved side as measured by both observers. Mean RV-angles were 0.8° vs 27.7° (P < 0.001). Paired differences averaged 26.8°, with a range from -18.4° to 77.8°. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the measurements. In two patients, retroversion increased on the involved side (Table 1). Age did not correlate with a decrease in humeral retroversion (r = -0.108, P = 0.538).

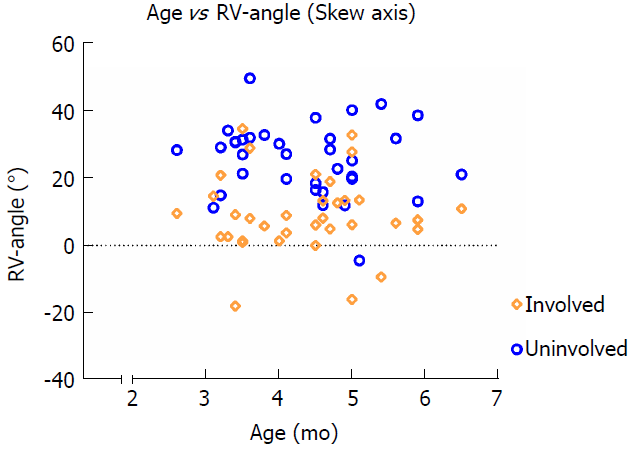

Retroversion measured according to the SA and the transepicondylar axis was also significantly decreased on the involved side, as measured by both observers. Mean RV-angles were 8.5° vs 25.4° (P < 0.001). Paired differences averaged 17.5°, with a range from -22.2° to 53.3°. Figure 3 shows the distribution of measurements. In five patients, retroversion was increased on the involved side (Table 1). Age was again not correlated with a decrease in humeral retroversion (r = -0.120, P = 0.492).

Both muscles were significantly smaller on the involved side. The IS muscle measured a mean surface area of 2.35 cm2vs 2.84 cm2 (83%) (P < 0.001), and the SSc muscle was 1.56 cm2vs 2.20 cm2 (70%) (P < 0.001).

Furthermore, the muscle ratio (SSc/IS) on the involved side was significantly smaller compared to the uninvolved side (P = 0.007). In Table 2, the results of the muscle cross-sectional area measurements are summarized.

| Muscle area, cm2 | Mean - involved | Mean - uninvolved | P value |

| Subscapularis muscle | 1.56 ± 0.315 | 2.20 ± 0.372 | < 0.001 |

| Infraspinatus muscle | 2.35 ± 0.520 | 2.84 ± 0.495 | < 0.001 |

| Ratio | 68.51 ± 16.90 | 78.88 ± 15.45 | 0.007 |

Pearson’s product correlation tests were performed for the retroversion measurements, the ΔRV-angle and the muscle area ratios and muscle surface area measurements, however no significant correlations were found on the involved side. When correlating age with decrease of retroversion, the Spearman Rho test was performed for retroversion measurement and Narakas’ score and passive external rotation, no significant correlations were found (P > 0.05).

For retroversion measured by HCL, the ICC for interrater reliability on the involved side was 0.934 (95%CI: 0.863-0.967; P < 0.001). The ICC for interrater reliability on the uninvolved side was 0.889 (95%CI: 0.747-0.948; P < 0.001). For retroversion measured using the SA, the ICC for interrater reliability on the involved side was 0.934 (95%CI: 0.897-0.970; P < 0.001). The ICC for interrater reliability on the uninvolved side was 0.923 (95%CI: 0.853-0.960; P < 0.001).

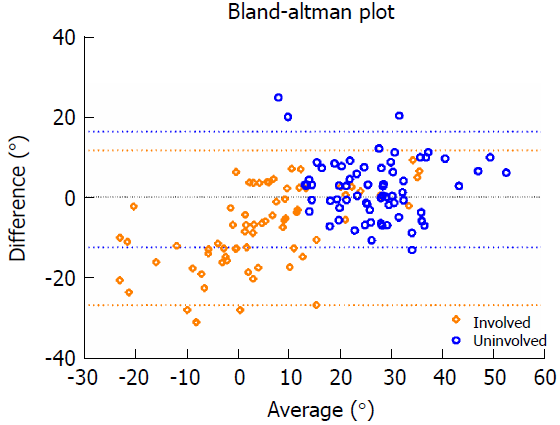

The distribution of measurements was larger on the involved side (Figure 4). Both measurement methods yielded comparable results in the uninvolved shoulder. However, the SA yielded systematically higher values in the deformed humeral head compared to the HCL.

We found a significant reduction of humeral retroversion on the involved side compared to the uninvolved side in a consecutive series of patients with internal rotation contractures secondary to BPBI. Additionally, the size of the SSc and IS muscles on the involved side was significantly decreased, as was the muscle ratio (SSc/IS) on the involved side compared to the uninvolved side.

Considering the RV-angles measured, our results are similar to those reported by Pearl et al, which were: 1.8° and 5.8° compared to 20.2° and 18.9°, respectively, depending on the method of measurement. However, the mean age of the study groups differed considerably, 3.2 years old vs 4.3 mo old. Our results suggest that declined humeral version is not something these children slowly grow into. The altered humeral version angle may already develop within the first weeks after birth, when the humerus is probably most prone to altered development caused by altered muscle forces gripping the humeral head. This is supported by the lack of significant correlation found between age and decreased retroversion on the involved side in both studies.

Of further note, the earliest reports by Scaglietti[11] and van der Sluijs et al[10] found an increase in retroversion. Scaglietti’s study was in a very different era of imaging technology and presented his observations with little quantitative data. van der Sluijs et al[10] utilized MRI, but nearly two decades ago in a somewhat older age group, when current software tools were not available for image analysis, and the lesser image quality might have influenced measurements. Perhaps these methodological differences explain these contradictory findings.

Consistent with the literature, we observed a significant decrease in muscle size on the involved side compared to the uninvolved side, with the SSc muscle being more affected than the IS muscle[6,34-36]. However, no significant correlation between the muscle ratio (SSc/IS) and the humeral RV-angle was observed. Nonetheless, the reduction in muscle ratio does not support the theory that the internal rotators overpower the injured (paralyzed) external rotators, but suggests that failure of the SSc to grow or develop may result in a contracted SSc, which restricts external rotation.

Another theory could be that the changes in humeral retroversion are partially related to injured muscles outside of the rotator cuff, perhaps those with at least some innervation outside of the original zone of injury. Further study of other muscles is warranted, looking for evidence as to whether they were also injured resulting in impaired growth[7,37], or whether they recovered so strongly that they overwhelmed their antagonists or are used differently in children with varying levels of recovery.

In addition, animal studies have shown that impaired longitudinal muscle growth and strength imbalance mechanisms are capable of producing shoulder deformities and impaired growth to a somewhat greater extent than muscle imbalance[8,38-41]. However, this has not yet been related to altered humeral version. For example, impaired growth and increased stiffness of the SSc muscle fibers may have a significant effect on humeral version development. In combination with other internal rotator muscles such as the pectoralis muscle, mechanical stiffness of these muscle fibers may not be directly related to cross-sectional muscle area measurements.

Further research is necessary to elucidate a causal relationship between those mechanisms and shoulder deformities, concerning both the humerus and glenoid, which will help guide clinical treatment decisions for BPBI.

This study has several limitations. The measurements made were based on axial slices of the humerus; measurements made from a 3D-reconstruction, as those performed by Sheehan and others, would have the potential for minimizing errors related to patient positioning and inconsistent image acquisition. In our studied age group, the humeral head and epicondylar axis are mostly cartilaginous, making 3D-reconstruction of the humeral anatomy much more challenging than in a skeletally mature subject. While the software tools currently exist, they are labor intensive and extremely difficult to implement in clinical practice. Therefore, we chose to utilize methods often used in our clinic setting and shown in a prior publication[12].

Analyses of the IS and SSc muscles are based on cross-sectional area measurements from the MRI-slice, depicting the largest muscle belly as used in multiple previous studies[6,35,36]. Capturing the full volume of both muscles would likely have been more informative; however, such software tools were not available to us. Furthermore, muscle thickness was only assessed for the IS and SSc muscles, and the measurement of other external and internal rotator muscles may offer additional insight into muscle behavior and its effect on humeral retroversion in this population.

The most common sequel and focus of surgical intervention in children with BPBI is an internal rotation contracture at the shoulder. These surgical interventions all aim for better function through an improved position of the hand in space. Humeral version undeniably affects hand functionality because with all other factors being equal, decreased humeral version results in an increase of the severity of the clinical presentation of an internal rotation contracture. A large reduction in humeral retroversion at a very young age could be a predictor (or an argument when apparent at an older age) for the necessity of a humeral derotational osteotomy to provide adequate improvement of hand and possibly elbow function. Furthermore, this study shows that secondary osseous changes can occur within several months in this patient population. A prospective study analyzing possible changes in humeral version in this patient population over time would be of interest, as it seems through these results and results from recent studies that changes in humeral version occur early, but that they may not change much after that.

In conclusion, humeral retroversion has a high likelihood of being significantly decreased in this patient population. These findings are relevant for any child under consideration for surgical intervention aiming to improve external rotation, since all other factors being equal, decreased humeral retroversion results in an increased severity of the clinical presentation of an internal rotation contracture. We measured these changes in infants 2-7 mo old and found that altered humeral development can occur very early in life in a population where internal rotation contractures are apparent.

The existing common treatment options for children suffering from brachial plexus birth palsy all strive for better function of the upper extremity through an improved position of the hand in space. This position is directly related to the humeral version angle.

Since earlier studies did not reveal a correlation between age and decreased retroversion on the involved side, the question remained at what age this anatomic change may occur.

Our objective was to elucidate the timing that decreased retroversion may occur; therefore, we included our youngest patient population (2-7 mo old).

We measured humeral version relative to two proximal axes and one distal axis (transepicondylar axis). The proximal axes were: (1) the perpendicular line to the borders of the articular surface (humeral centerline), and (2) the longest diameter through the humeral head. Additionally, cross-sectional areas of the infraspinatus (IS) and subscapularis (SSc) muscles were measured. The difference in retroversion was correlated with the ratio of muscle sizes.

Retroversion on the involved side was significantly decreased, 1.0° vs 27.6° (1) and 8.5° vs 27.2° (2), (P < 0.01), as compared to the uninvolved side. SSc and IS muscle size on the involved side was significantly decreased, 2.26 cm² vs 2.79 cm² and 1.53 cm² vs 2.19 cm², respectively (P < 0.05). Additionally, muscle ratio (SSc/IS) on the involved side was significantly smaller compared to the uninvolved side (P = 0.007), but was not related to alterations in humeral version.

Our results show that altered humeral development can occur very early in life in a population where internal rotation contractures are apparent.

A large reduction in humeral retroversion at a very young age could be a predictor (or an argument when apparent at an older age), for the necessity of a humeral derotational osteotomy, to provide adequate improvement of hand and possibly elbow function. A prospective study analyzing changes in humeral version over time would be of interest to assess the predictive value of decreased retroversion at such a young age, concerning various treatment options (soft-tissue and bony).

| 1. | Pearl ML, Edgerton BW. Glenoid deformity secondary to brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:659-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pearl ML, Woolwine S, van de Bunt F, Merton G, Burchette R. Geometry of the proximal humeral articular surface in young children: a study to define normal and analyze the dysplasia due to brachial plexus birth palsy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:1274-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kozin SH. Correlation between external rotation of the glenohumeral joint and deformity after brachial plexus birth palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:189-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Waters PM, Smith GR, Jaramillo D. Glenohumeral deformity secondary to brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:668-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | van der Sluijs JA, van Ouwerkerk WJ, de Gast A, Wuisman PI, Nollet F, Manoliu RA. Deformities of the shoulder in infants younger than 12 months with an obstetric lesion of the brachial plexus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:551-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Waters PM, Monica JT, Earp BE, Zurakowski D, Bae DS. Correlation of radiographic muscle cross-sectional area with glenohumeral deformity in children with brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2367-2375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nikolaou S, Peterson E, Kim A, Wylie C, Cornwall R. Impaired growth of denervated muscle contributes to contracture formation following neonatal brachial plexus injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:461-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Soldado F, Fontecha CG, Marotta M, Benito D, Casaccia M, Mascarenhas VV, Zlotolow D, Kozin SH. The role of muscle imbalance in the pathogenesis of shoulder contracture after neonatal brachial plexus palsy: a study in a rat model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1003-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sheehan FT, Brochard S, Behnam AJ, Alter KE. Three-dimensional humeral morphologic alterations and atrophy associated with obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:708-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van der Sluijs JA, van Ouwerkerk WJ, de Gast A, Wuisman P, Nollet F, Manoliu RA. Retroversion of the humeral head in children with an obstetric brachial plexus lesion. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:583-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Scaglietti O. The obstetrical shoulder trauma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1938;pp. 868-877. |

| 12. | Pearl ML, Batech M, van de Bunt F. Humeral Retroversion in Children with Shoulder Internal Rotation Contractures Secondary to Upper-Trunk Neonatal Brachial Plexus Palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1988-1995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Krahl VE. The torsion of the humerus; its localization, cause and duration in man. Am J Anat. 1947;80:275-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Edelson G. The development of humeral head retroversion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:316-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cowgill LW. Humeral torsion revisited: a functional and ontogenetic model for populational variation. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;134:472-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Edelson G. Variations in the retroversion of the humeral head. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:142-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yamamoto N, Itoi E, Minagawa H, Urayama M, Saito H, Seki N, Iwase T, Kashiwaguchi S, Matsuura T. Why is the humeral retroversion of throwing athletes greater in dominant shoulders than in nondominant shoulders? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:571-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Whiteley R, Adams R, Ginn K, Nicholson L. Playing level achieved, throwing history, and humeral torsion in Masters baseball players. J Sports Sci. 2010;28:1223-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chant CB, Litchfield R, Griffin S, Thain LM. Humeral head retroversion in competitive baseball players and its relationship to glenohumeral rotation range of motion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:514-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Myers JB, Oyama S, Rucinski TJ, Creighton RA. Humeral retrotorsion in collegiate baseball pitchers with throwing-related upper extremity injury history. Sports Health. 2011;3:383-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Osbahr DC, Cannon DL, Speer KP. Retroversion of the humerus in the throwing shoulder of college baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:347-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pearl ML, Edgerton BW, Kazimiroff PA, Burchette RJ, Wong K. Arthroscopic release and latissimus dorsi transfer for shoulder internal rotation contractures and glenohumeral deformity secondary to brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:564-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kozin SH, Boardman MJ, Chafetz RS, Williams GR, Hanlon A. Arthroscopic treatment of internal rotation contracture and glenohumeral dysplasia in children with brachial plexus birth palsy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:102-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Waters PM, Bae DS. The effect of derotational humeral osteotomy on global shoulder function in brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1035-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gilbert A, Brockman R, Carlioz H. Surgical treatment of brachial plexus birth palsy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;39-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kirkos JM, Kyrkos MJ, Kapetanos GA, Haritidis JH. Brachial plexus palsy secondary to birth injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:231-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Birch R. Obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Boileau P, Bicknell RT, Mazzoleni N, Walch G, Urien JP. CT scan method accurately assesses humeral head retroversion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:661-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | DeLude JA, Bicknell RT, MacKenzie GA, Ferreira LM, Dunning CE, King GJ, Johnson JA, Drosdowech DS. An anthropometric study of the bilateral anatomy of the humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:477-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Harrold F, Wigderowitz C. A three-dimensional analysis of humeral head retroversion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:612-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hernigou P, Duparc F, Hernigou A. Determining humeral retroversion with computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1753-1762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Matsumura N, Ogawa K, Kobayashi S, Oki S, Watanabe A, Ikegami H, Toyama Y. Morphologic features of humeral head and glenoid version in the normal glenohumeral joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1724-1730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32742] [Cited by in RCA: 33274] [Article Influence: 831.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 34. | Hogendoorn S, van Overvest KL, Watt I, Duijsens AH, Nelissen RG. Structural changes in muscle and glenohumeral joint deformity in neonatal brachial plexus palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:935-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Van Gelein Vitringa VM, Jaspers R, Mullender M, Ouwerkerk WJ, Van Der Sluijs JA. Early effects of muscle atrophy on shoulder joint development in infants with unilateral birth brachial plexus injury. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:173-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pöyhiä TH, Nietosvaara YA, Remes VM, Kirjavainen MO, Peltonen JI, Lamminen AE. MRI of rotator cuff muscle atrophy in relation to glenohumeral joint incongruence in brachial plexus birth injury. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:402-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Einarsson F, Hultgren T, Ljung BO, Runesson E, Fridén J. Subscapularis muscle mechanics in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:507-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Crouch DL, Hutchinson ID, Plate JF, Antoniono J, Gong H, Cao G, Li Z, Saul KR. Biomechanical Basis of Shoulder Osseous Deformity and Contracture in a Rat Model of Brachial Plexus Birth Palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1264-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Li Z, Barnwell J, Tan J, Koman LA, Smith BP. Microcomputed tomography characterization of shoulder osseous deformity after brachial plexus birth palsy: a rat model study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2583-2588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Li Z, Ma J, Apel P, Carlson CS, Smith TL, Koman LA. Brachial plexus birth palsy-associated shoulder deformity: a rat model study. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:308-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Soldado F, Benito-Castillo D, Fontecha CG, Barber I, Marotta M, Haddad S, Menendez ME, Mascarenhas VV, Kozin SH. Muscular and glenohumeral changes in the shoulder after brachial plexus birth palsy: an MRI study in a rat model. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj. 2012;7:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Netherlands

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Emara KM, Wyatt MC S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Bian YN