Published online Oct 18, 2018. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i10.229

Peer-review started: April 19, 2018

First decision: June 15, 2018

Revised: June 28, 2018

Accepted: July 10, 2018

Article in press: July 10, 2018

Published online: October 18, 2018

Processing time: 182 Days and 17.7 Hours

To determine the functional outcomes, complications and revision rates following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in patients with Paget’s disease of bone (PDB).

A systematic review of the literature was performed. Four studies with a total of 54 TKAs were included for analysis. Functional outcomes, pain scores, complications and revision rates were assessed. The mean age was 72.0 years and the mean follow-up was 7.5 years.

All studies reported significant improvement in knee function and pain scores following TKA. There were 2 cases of aseptic loosening, with one patient requiring revision of the femoral component 10 years after the index procedure. Malalignment, bone loss, soft tissue contractures were the most commonly reported intra-operative challenges. There were five cases (9%) that were complicated by intra-operative patellar tendon avulsion.

The findings support the use of TKA in patients with PDB. The post-operative functional outcomes are largely similar to other patients, however there are specific perioperative challenges that have been highlighted, in particular the high risk for patellar tendon avulsion.

Core tip: Patients with Paget’s disease of the bone commonly develop significant mal-alignment, structural bone deformities and soft tissue contractures, making total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in this patient group challenging. In addition, exposure of the knee joint can prove particularly difficult, with this review demonstrating a high incidence of patella tendon avulsion. This systematic review has demonstrated that TKA improves pain and functional outcomes in patients with Paget’s disease of the bone. The rate of loosening and revision in this patient group appears comparable to other patients undergoing TKA.

- Citation: Popat R, Tsitskaris K, Millington S, Dawson-Bowling S, Hanna SA. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with Paget’s disease of bone: A systematic review. World J Orthop 2018; 9(10): 229-234

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v9/i10/229.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v9.i10.229

Sir James Paget first described Paget’s disease of bone (PDB) as “osteitis deformans” in 1877[1]. PDB is a bone disorder that typically manifests in middle-aged patients and affects approximately 2%-4% of people older than 40 years. It is a chronic affliction of adult bone, which undergoes aggressive osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, followed by abnormal osteoblast-mediated bone repair[2].

Although the exact etiology is still unknown, PDB is thought to result from a viral infection in genetically predisposed individuals[3]. The disease process evolves through three distinct phases. Initially, there is an osteolytic phase with a collection of destructive osteoclasts spreading to encompass the entire bone. This is followed by a mixed osteolytic and osteoblastic phase, and finally by the osteoblastic or sclerotic phase[4]. This process results in bone that is mechanically weaker, larger, less compact, more vascular and more susceptible to fracture than normal adult lamellar bone[3].

PDB is slightly more common in men and more prevalent in Europe, North America and Australasia[5,6]. It can affect any bone but is most commonly found in the pelvis, skull, lumbosacral spine, femur or tibia, and is polyostotic in 75% of cases[7].

PDB is usually asymptomatic and only 5%-10% of patients with the disease experience any symptoms, most commonly poorly localized bone pain. Patients may also present with bone deformity, fracture, skin temperature changes, or neurological complications[8]. Concurrent symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee affects 10%-12% of individuals with PDB[8]. Differentiating the pain of PDB from osteoarthritis of the knee joint can be challenging as both can give a dull ache that may worsen with weight bearing[2]. An intra-articular injection with local anaesthetic can help solve the diagnostic conundrum, as relief of the symptoms would suggest osteoarthritis as the source of pain. Similarly, pain due to PDB can be improved with medication, such as bisphosphonates and calcitonin, further assisting in clarifying the diagnosis.

The non-operative management of osteoarthritis in patients with PDB involves activity and lifestyle modifications, physical therapy, analgesics, functional bracing and anti-Paget’s medication. If these fail to alleviate the pain, surgical intervention in the form of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is indicated. The disease process characterized by bone expansion, softening, cortical thickening and hypervascularity can lead to sclerotic bone, deformity and soft tissue contractures around the knee joint[9]. Marked bone loss and large bone cysts have also been described. These morphological changes can present specific technical challenges when performing TKA in patients with PDB.

With the number of TKAs performed each year growing rapidly, there is a high likelihood that arthroplasty surgeons will increasingly need to perform TKA in patients with PDB. Understanding the challenges associated with this group of patients is, hence, very important. We have, therefore, performed a systematic review of the literature to determine the functional outcomes, failure rates and complication rates of TKA in patients with PDB of the knee.

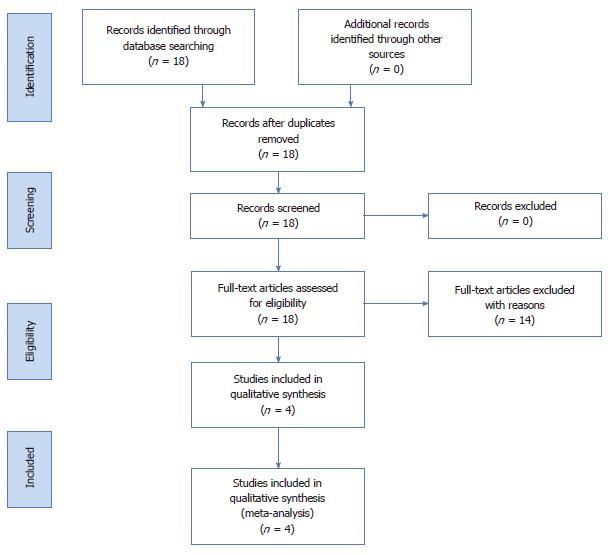

A search of Medline and EMBASE was performed on 01/03/2018. The keywords used for the searches were “total knee arthroplasty” or “total knee replacement” and “Paget’s disease”. All relevant studies in the English literature describing the results of TKA in patients with PDB, between 1986 and 2017, were identified in accordance with the PRISMA statement. We also identified relevant studies or reviews by assessing the bibliographies of all papers that were included.

All papers that described the results of TKA in patients with PDB published in the English language were included. All the articles adhered to the PICO Criteria for systematic reviews (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes).

One reviewer (Ravi Popat) scrutinised the articles and collected the data using a standardised data collection form. All information relating to the number of patients, their demographics, follow-up period, complications, revision rates and functional outcomes were entered in a spreadsheet. Another reviewer (KT) checked the accuracy of the data collection. There were no inconsistent results.

The results were summarized using descriptive statistics for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Microsoft Excel, 2016 version (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington) was used for data analysis.

The literature search identified 18 articles. The full text of each article was reviewed. A total of 4 studies satisfied the eligibility criteria. Figure 1 outlines the search strategy.

All studies were small to medium retrospective case series (n = 7-21 patients) describing the outcome of TKA in patients with PDB. The range of follow-up in these studies was from 2 to 20 years.

The studies included 54 TKAs performed in patients with PDB. These patients had a mean age of 72 years (range, 57-86 years) with an average follow-up of 7.5 years (range, 2-20 years). Table 1 summarises the patient demographics.

| Ref. | No. of knees | Age (yr) | Follow up (yr) | Complications | Revision rate | Functional outcomes |

| Lee et al[10], 2005, United States | 21 | 71 (57-85) | 9 (2-20) | Patellar tendon avulsion (3/21) | 1 (4.8%) | Knee Society Pain Score 41 to 87 |

| Gabel et al[8], 1991, United States | 15 | 72 (61-85) | 7 (2-15) | Aseptic loosening (1/15) Patella tendon avulsion (1/16) Femoral notching (2/21) | 0 | Knee Society Pain Score 42 to 88 Knee Society Functional Score 33 to 86 |

| Schai et al[11], 1999, United States | 11 | 75 (59-86) | 5.7 (2-16) | Patellar tendon avulsion (1/11) Necrosis of patella (1/11) | 0 | Knee Society Pain Score 83 (post-op only) Knee Society Functional Score 62 (post-op only) |

| Broberg et al[12], 1986, United States | 7 | 71 (66-85) | 6.6 (3-12) | Partial patellar tendon avulsion (1/7) | 0 | No pain - 5 Mild Pain - 2 (post-operatively) |

Functional outcome: All the studies reported improvement in knee function following TKA. Two studies reported a pre and post-operative comparison of the Knee Society Score (KSS) and demonstrated an average improvement of 42 points post-operatively[8,10]. Schai et al[11] provided post-operative functional scores only, with a mean of 62.

Pain outcome: All the studies reported an improvement in pain scores post-operatively. Two studies demonstrated an average improvement of 46 points post-operatively[8,10]. The average pain score for patients in Schai et al[11] was 83. Five out of 7 patients in the cohort from Broberg et al[12] reported no post-operative pain. The remaining patients reported mild pain.

There were 2 cases of aseptic loosening out of a total of 54 cases. There was one revision of the femoral component, 10 years after the index procedure.

Difficulties during the surgical approach, soft tissue contractures and thickening of the patellar tendon were described in all studies. A total of 5 out of 54 patients (9.3%) had patellar tendon avulsion intra-operatively.

TKA has been shown to be a generally successful procedure in patients with PDB. All the studies that were included in this systematic review reported a post-operative improvement in knee function and pain scores. Furthermore, the overall rate of aseptic loosening was 3.7% in 7.5 years, and the revision rate was 1.85%, with one revision of the femoral component 10 years after the index procedure. This failure rate is comparable to other patients undergoing TKA. According to the most up to date report of the National Joint Registry, a revision rate of 1.85% at 7.5 years is considered reasonable[13].

The overall reported incidence of patellar tendon avulsion was 9.3%. This is an extraordinarily high incidence for this complication and surgeons undertaking TKA in the context of PDB should be aware of interventions that can help prevent it. We are discussing such interventions in a dedicated paragraph later in this review. Conversely, although the incidence of heterotopic bone (HO) formation has been reported to be as high as 46% following total hip arthroplasty for PDB, HO does not appear to be a concern following TKA[14].

The studies included in this review reported on a variety of TKA implants with variable levels of constraint. Some of these implants are also historical. Due to the small number of cases and the wide variation of implant type and constraint, further analysis of potential subgroups, such as cruciate retaining vs posterior stabilised, or cemented vs uncemented, was not feasible.

The main challenges when performing TKA in the context of PDB are malalignment (more commonly varus), extensive bone loss, soft tissue contractures and thickening of the patellar tendon. With the steadily increasing number of TKAs performed annually, it is reasonable to expect that there will be a proportional increase in the burden of PDB cases. It is, therefore, important to employ a systematic approach in order to ensure optimal outcomes.

Initially, it is very important to isolate articular pain from the deep and aching pain that is associated with the later stages of Paget’s disease. The use of intra-articular injections can help to identify and delineate whether the patient’s pain is from an intra-articular source, providing greater certainty that an arthroplasty procedure will alleviate the patient’s symptoms.

Good quality, full-length radiographs are recommended to establish the type of alignment of the affected limb and to assist in pre-operative planning. Long leg views can also identify potential deformity in the femur, which needs to be considered when using intra-medullary cutting guides. The use of CT scans has grown in popularity in the last two decades and can display information related to bony morphology that is not available on plain radiographs.

Pre-operative assessment and optimisation of haemoglobin and cardiac function is recommended. The hypervascularity of pagetoid bone means that these patients are in a high cardiac output state, which can have implications for the anaesthetic intervention. The use of bisphosphonates or calcitonin can reduce the disease activity and theoretically reduce blood loss, however, this has not been established. Pre-operative autologous blood donations may also be considered.

The morphological changes that occur in bones affected by PDB may require intra-operative adaptations and pre-emptive precautionary measures. PDB around the knee is characterised by enlarged bones and correspondingly larger joint surfaces. A size mismatch between the femoral and tibial components is often encountered, especially in cases where there is isolated involvement of either the tibia or the femur. Additionally, the arthritic changes may be more pronounced, with extensive bone loss, large bone cysts and tight collateral ligaments[8,11].

Exposure of the knee joint can prove particularly challenging because of joint stiffness, particularly in case of thickening of the patellar tendon. Patellar eversion can result in avulsion of the patellar tendon and this was described as a complication in 5 out of 54 patients. Schai et al[11] recommended that the patellar preparation should be performed early during the procedure to allow for improved exposure. Vail and Callaghan[14] also advised for early patellar preparation, but also performed lateral releases to help achieve adequate exposure. Pre-emptive measures to protect the patellar tendon insertion are essential, especially in cases where there is pagetoid involvement of the tibial tuberosity.

Significant varus or valgus malalignment in this patient group presents challenges both due to the respective bone loss and in achieving optimal soft tissue balancing. Extensive medial or lateral releases may be required in order to achieve adequate exposure as well as to help balance the joint, although the latter may not be feasible with low-constraint implants.

Disease-involvement of the femur, especially in the context of increased varus angulation of the distal femur can present a challenge when intra-medullary guides are used to plan the distal femoral cuts[15]. It has been previously reported that intramedullary guidance may lead to mal-positioning of the femoral components. It has been recommended that extra-medullary guides are preferable for the preparation of both the femur and tibia[8].

On the tibial side, there can be significant anterior tibial bowing and the use of an extra-medullar tibial cutting guide may lead to excessive bone loss. In order to preserve tibial bone, Gabel et al[8] have recommended utilising a tibial cutting guide with 10 degrees of posterior slope and then using a flat tibial component.

Hard sclerotic bone can often be found in the proximal tibia and the use of a tibial punch during preparation of the bone may lead to fractures. It has been recommended that a high-speed burr should be utilised for the preparation of the proximal tibia, instead of a tibial punch[16]. Additionally, the presence of sclerotic bone and its tendency to bleed, may have a bearing on cement interdigitation.

Due to bone hypervascularity and the high cardiac output state present in many of these patients, the use of tranexamic acid and blood salvage techniques should be considered.

Bisphosphonate therapy should continue if disease activity is high (as measured using ALP levels). The main limitation of this review is that it included largely historical studies. Three of the papers were published in the 20th century and the fourth more than a decade ago. Nevertheless, the overall results were still favourable. With the number of arthroplasty procedures performed each year increasing rapidly, and with PDB being relatively common, we feel that this review is relevant to current and future clinical practice.

The findings of this review support the use of TKA to alleviate the functional limitation and pain due to osteoarthritis in patients with PDB. Post-operative pain relief and functional improvement appear to be significant and comparable to other patients. Surgeons that treat this unique group of patients need to be aware of the particular challenges and interventions that are essential for optimal outcomes.

Paget’s disease of bone (PDB) affects approximately 2%-4% of people older than 40 years. With an ageing population and the number of TKAs performed each year growing rapidly, there is a high likelihood that arthroplasty surgeons will need to perform total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in patients with PDB.

Patients with PDB can develop significant mal-alignment, structural bone deformities and soft tissue contractures. Understanding the problems and challenges associated with performing TKA in patient with PDB is key to achieving successful outcomes.

To aid appropriate consenting of patients and to assist surgeons in achieving the best outcomes for their patients, it is important to understand the outcomes that have previously been achieved following TKA in patients with PDB.

A systematic review of the literature was performed. A total of 54 TKAs were included for analysis. Functional outcomes, pain scores, complications and revision rates were assessed.

All studies demonstrated a substantial improvement in function and pain following TKA in patients with PDB. The mean follow-up was 7.5 years. There were two cases of aseptic loosening, with one patient requiring a revision TKA at 10 years. Five cases (9%) of intra-operative patellar tendon avulsion were reported, suggesting that exposure of the knee joint in patient with PDB can be particularly challenging.

This systematic review supports the use of TKA to improve function and alleviate pain in patients with Paget’s disease around their knee joints. The post-operative functional outcomes appear to be similar to those experienced by patients that do not have PDB. At an average of 7.5 years follow-up, implant survival appears comparable with patients that receive TKA for primary OA. Pain scores also improve substantially in this patient group. Morphological changes that occur secondary to PDB, may require intra-operative adaptations and a high rate of patella tendon avulsion (9%) suggests additional care needs to be taken when gaining access to the knee joint, especially in case where there is Pagetoid involvement of the patella/tibial tuberosity.

Surgeons treating patients with PDB need to be aware of the particular challenges posed by this patient group, with intra-operative adaptations potentially required to avoid complications. Further studies that compare functional, pain and revision outcomes in patient with PDB around the knee, against a matched control group, with the use of modern TKA implants, will provide further information about the results that can be expected in this patient group.

| 1. | Paget J. On a Form of Chronic Inflammation of Bones (Osteitis Deformans). Med Chir Trans. 1877;60:37-64.9. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Whyte MP. Clinical practice. Paget’s disease of bone. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:593-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rebel A, Basle M, Pouplard A, Malkani K, Filmon R, Lepatezour A. Towards a viral etiology for Paget’s disease of bone. Metab Bone Dis Relat Res. 1981;3:235-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lander PH, Hadjipavlou AG. A dynamic classification of Paget’s disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:431-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Doyle T, Gunn J, Anderson G, Gill M, Cundy T. Paget’s disease in New Zealand: evidence for declining prevalence. Bone. 2002;31:616-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, Lyles K, Sprafka JM, Cooper C. Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:465-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kanis JA. Pathophysiology and treatment of Paget’s disease of bone. 2nd ed. London: Martin Dunitz 1998; 310. |

| 8. | Gabel GT, Rand JA, Sim FH. Total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthrosis in patients who have Paget disease of bone at the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:739-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Smith SE, Murphey MD, Motamedi K, Mulligan ME, Resnik CS, Gannon FH. From the archives of the AFIP. Radiologic spectrum of Paget disease of bone and its complications with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22:1191-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee GC, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Berry DJ. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with Paget’s disease of bone at the knee. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:689-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schai PA, Scott RD, Younger AS. Total knee arthroplasty in Paget’s disease: technical problems and results. Orthopedics. 1999;22:21-25. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Broberg MA, Cass JR. Total knee arthroplasty in Paget’s disease of the knee. J Arthroplasty. 1986;1:139-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | National Joint Registry Annual Report. National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. Available from: http://www-new.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/Home/tabid/36/Default.aspx. |

| 14. | Vail TP, Callaghan JJ. Total knee replacement with patella magna and pagetoid patella. Orthopedics. 1995;18:1174-1177. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Parvizi J, Klein GR, Sim FH. Surgical management of Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21 Suppl 2:P75-P82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cameron HU. Total knee replacement in Paget’s disease. Orthop Rev. 1989;18:206-208. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Angoules A, Drosos GI, Georgiev GPP S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H