Peer-review started: April 1, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Revised: June 15, 2016

Accepted: July 14, 2016

Article in press: July 18, 2016

Published online: January 18, 2017

Processing time: 284 Days and 20.2 Hours

Odontoid fractures account for 5% to 15% of all cervical spine injuries and 1% to 2% of all spine fractures. Type II fractures are the most common fracture pattern in elderly patients. Treatment (rigid and non-rigid immobilization, anterior screw fixation of the odontoid and posterior C1-C2 fusion) remains controversial and represents a unique challenge for the treating surgeon. The aims of treatment in the elderly is to quickly restore pre-injury function while decreasing morbidity and mortality associated with inactivity, immobilization with rigid collar and prolonged hospitalization. Conservative treatment of type II odontoid fractures is associated with relatively high rates of non-union and in a few cases delayed instability. Options for treatment of symptomatic non-unions include surgical fixation or prolonged rigid immobilization. In this report we present the case of a 73-year-old woman with post-traumatic odontoid non-union successfully treated with Teriparatide systemic anabolic therapy. Complete fusion and resolution of the symptoms was achieved 12 wk after the onset of the treatment. Several animal and clinical studies have confirmed the potential role of Teriparatide in enhancing fracture healing. Our case suggests that Teriparatide may have a role in improving fusion rates of C2 fractures in elderly patients.

Core tip: Odontoid fractures are common in elderly patients and treatment of these injuries remains challenging. Conservative management consists of rigid immobilization with collar or Halo vest. Delayed union or non-union is a common outcome in patients treated conservatively. For a symptomatic non-union, surgery may be the only option. In this case report we discuss the case of a patient with an odontoid fracture non-union successfully treated with systemic anabolic Teriparatide therapy. A complete fusion was achieved after 12 wk of treatment. Teriparatide therapy may have a role in fostering fusion of C2 fractures in elderly patients.

- Citation: Pola E, Pambianco V, Colangelo D, Formica VM, Autore G, Nasto LA. Teriparatide anabolic therapy as potential treatment of type II dens non-union fractures. World J Orthop 2017; 8(1): 82-86

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v8/i1/82.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v8.i1.82

Odontoid fractures comprise 5% to 15% of all cervical spine fractures and represent the most common cervical spine injury in elderly patients (> 65-year-old)[1,2]. Type II fractures (i.e., a fracture through the base of the dens, below the transverse ligament) account for the majority of cases (67%). Odontoid fractures in the elderly are a potentially life threatening injury. Acute respiratory arrest and spinal cord injury have been described following fracture displacement. More commonly, patients present with acute neck pain and occasional occipital neuropathic pain. Reduced mobility, chronic pain, and the presence of multiple medical comorbidities often lead to a progressive decline of the health status and excess mortality in elderly patients. In a retrospective review, mortality risk at 1 year following a cervical fracture in patients > 65 years of age was 28%[3].

There is a lack of agreement regarding the optimal treatment of odontoid fractures in the elderly. The aim of treatment is to stabilize the fracture to prevent neurological damage and allow early and safe mobilization. Treatment options include conservative management (i.e., hard collar and Halo vest immobilization) or surgical fixation. Surgery provides the advantage of early mobilization and higher fusion rates. However, it is also associated with high complication rates and perioperative morbidity[4]. Conservative management is a safer option but is associated with higher risk of delayed union or non-union (77%) and increased morbidity due to prolonged immobilization[5].

Factors determining the poor healing potential of odontoid fractures in the elderly are poorly understood. Known factors associated with higher risk of nonunion include age > 50, displacement greater than 6 mm, posterior displacement, angulation of the fragments, and smoking[6,7]. The role of segmental osteoporosis and poor osteoblastic response is less clearly defined but is commonly perceived as a potentially important factor in determining facture healing potential. Teriparatide (i.e., rhPTH1-34) is the recombinant form of the biologically active component of the human parathyroid hormone. It is a novel anabolic drug therapy for osteoporosis which has also been shown to stimulate osteoblasts and enhance fracture healing in vivo. The aim of this study is to report our experience with the use of rhPTH1-34 in the treatment of a non-union type II dens fracture in an elderly patient.

A 73-year-old woman was transferred to our emergency department following a road traffic accident. The patient was a restrained passenger of a car, the driver lost the control of the vehicle and the car fell into a ditch at the side of the road. The patient lost consciousness at the impact but was found alert and oriented at the time of the arrival of the ambulance. Patient observations were stable and there were no signs of other bone injuries. Patient had no neurological deficits and cranial nerves were intact. Past medical history of the patient included acute glaucoma and visual impairment.

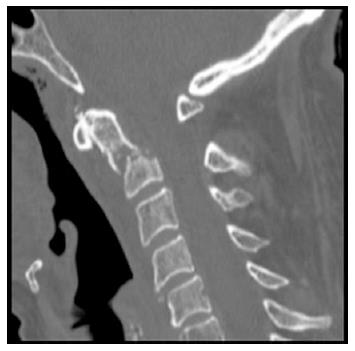

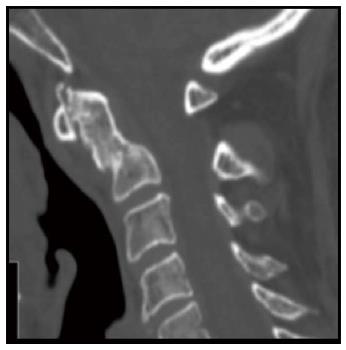

A routine trauma series CT-scan was performed and showed a type II odontoid fracture with anterior displacement (Figure 1). Patient was referred to our spinal unit and, after appropriate counselling, elected a non-operative treatment. Cervical spine was stabilized with a Philadelphia collar and patient was discharged home 3 d after the injury. The first outpatient clinic appointment was booked at 2 wk after discharge and patient was seen at regular intervals thereafter. Six months following the injury the patient was still complaining of significant axial neck pain requiring regular pain killer. An interval computed tomography (CT) scan at 6 mo after the injury revealed a non-union at the fracture site, distance between fracture fragments was 4 mm and there was evidence of sclerotic bone margins at the level of the fracture (Figure 2). Surgical options were discussed with the patient at this stage, but she again refused any surgical intervention.

Patient was maintained in rigid collar and was offered off-label therapy with daily subcutaneous injections of Teriparatide (rhPTH1-34) 20 μg/d which she accepted. This is the same regime used for treatment of osteoporosis in post-menopausal women. The anabolic treatment with Teraparatide was monitored through periodic examinations and regular measurements of serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone and alkaline phosphatase.

Forty-five days after starting Teriparatide treatment, an interval CT scan showed an initial phase of callus formation at the fracture site with partial closure of the fracture gap. Anabolic therapy was continued for 3 mo, at the end of the treatment a final CT scan confirmed a complete consolidation of the fracture (Figure 3). Flexion/extension X-rays of the cervical spine showed no residual instability, and axial neck pain had resolved as well. Mean Visual Analogic Scale score at the end of the treatment was 3 (from a baseline value of 8), whilst SF-12P score was 45.1 and the SF-12M score was 58 (from baseline values of 29.4 for SF-12P and 28.7 for SF-12M). The Neck Disability Index decreased from 70% to 15% at the time of last follow-up. No side effects related to the use of Teriparatide were noted in our patient.

The number of elderly patients is growing rapidly in western countries and worldwide. By 2025, one fifth of the world population will be over the age of 65 and the number of osteoporotic and fragility fractures are expected to rise accordingly. Odontoid fractures are common in elderly patients, and treatment remains controversial. Although modern surgical techniques (i.e., C1-C2 transarticular and C1-C2 polyaxial screw fixation) allow significantly higher fusion rates (83%-100%) than traditional techniques, they remain technically demanding and are associated with a sizable perioperative complication rate[8-10]. Reported fusion rate for conservative management varies from 23% to 46%[7,11]. It is safer than surgery in the short term, but associated with prolonged immobilization and reduced mobility. Cranial, pulmonary and cardiac complications have all been reported in patients treated with rigid immobilization. Furthermore, the development of a fibrous non-union is a common finding in patients treated conservatively. Although achievement of a stable fibrous non-union is regarded as an acceptable outcome in elderly patients by some authors, there are cases described of late onset cervical myelopathy in patients with non-union of the odontoid process[12].

Teriparatide (rhPTH1-34) is a novel Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drug for treatment of post-menopausal osteoporosis. Teriparatide is a recombinant form of the N-terminal 1-34 fragment of the human parathyroid hormone (PTH). In humans, PTH regulates blood calcium levels by controlling renal calcium reabsorption and release of calcium from the skeleton. As such, continuous high levels of PTH determine progressive bone demineralization and systemic osteoporosis. Interestingly, the intermittent administration of PTH has opposite effects on bone metabolism and stimulates new bone formation (i.e., anabolic action)[13]. Teriparatide is the only currently available drug with anabolic effect on bone metabolisms. It is FDA approved for use in patients with severe post-menopausal osteoporosis (i.e., in women with a history of osteoporotic fractures or who are not responsive to other osteoporosis therapies) and can be administered for a maximum of 24 mo.

Several studies have investigated the role of Teriparatide in accelerating fracture healing and non-unions. In 1999 and 2001, Andreassen et al[14,15] reported the effects of systemic intermitted PTH treatment in a rat model of fracture healing. Treated animals showed increased fracture strength and callus volume at 8 wk after treatment. In 2010, similar findings were published by Mognetti et al[16] in a mouse model of tibial fracture. The authors noted a stimulation of callus formation with Teriparatide dosage of 40 μg/kg per day; 15 d after treatment callus mechanical strength approximated normal bone. The anabolic effect of Teriparatide administration is not limited to the period of treatment as shown by Alkhiary et al[17] in a rat model. The authors showed that 49 d after discontinuing anabolic treatment, treated animals were still showing a continuous increase of bone mineral density and torsional strength[17]. The anabolic effect of Teraparatide administration has also been confirmed in animal models of delayed bone healing[18].

The effects of Teriparatide on human fracture healing have been investigated by several authors with contrasting results. In the only Level I study on this topic, Aspenberg et al[19] have studied a cohort of 102 post-menopausal patients with distal radius fractures treated conservatively. Median time to radiographic healing was 9.1 wk in the control group, and 7.4 and 8.8 wk in the groups treated with 20 μg and 40 μg of Teriparatide, respectively. The differences between the groups were not statistically significant[19]. Opposite results have been reported by Peichl et al[20] in a series of 65 post-menopausal women with pubic bone fracture treated with the 1-84 form of PTH. The median healing time was 7.8 wk for the treatment group vs 12.6 wk for the control group[20]. The only available data on the effects of anabolic treatment on spinal fractures healing have been reported by Bukata et al[21] in 2010. The authors studied a cohort of 145 patients with spinal or appendicular skeleton fractures. Fracture healing rate was 93% at 12 wk after treatment with Teriparatide.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has systematically investigated the role of Teriparatide in cervical spine fractures. The only available study on this topic is a case report by Rubery et al[22] published in 2010. The authors reported on 3 patients with painful delayed unions of type III odontoid fractures. All 3 patients were started on therapeutic doses of Teriparatide and experienced complete resolution of their symptoms and complete union[22]. In this study, we report the case of a painful delayed union of a type II odontoid fracture. Our patient presented with persistent pain and failed conservative treatment of the fracture. Teriparatide treatment was started 6 mo after the index injury and a complete fusion with resolution of the symptoms was observed 12 wk after the onset of the therapy.

The nature of our study does not allow a generalization of our results. It is impossible to know whether our patient would have developed a non-painful fibrous non-union at a later follow-up. Also, complete bone union can be observed as long as 9-12 mo after the index injury. Nevertheless, we think our case report raises an important point in the management of this very common injury in elderly patients. Teriparatide may represent a useful adjunct to the armamentarium of the clinician for treatment of painful cervical non-unions in frail elderly patients. We believe that a prospective study on the effects of anabolic therapy in type II odontoid fractures could have a profound impact on the management and outcomes of frail elderly patients.

We described a case of a painful non-union of type II odontoid fracture in an elderly patient treated conservatively. Due to no improvement in her symptoms and no progress of radiological union we offered our patient systemic treatment with rhPTH1-34 (Teriparatide) for 3 mo. At the end of the treatment a stable union of the fracture was achieved with complete resolution of the pain. Our report suggests that Teriparatide may have a role in enhancement of fracture healing in elderly patients with odontoid fractures.

There was no external funding source and no funding source that played a role in the investigation. The work was undertaken at the Spinal Unit, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, of the Catholic University of Rome, Italy.

A 73-year-old woman with type II odontoid fracture. Treated conservatively with Philadelphia collar. Patient presented at 6 mo with ongoing mechanical neck pain with no neurological deficits.

Painful non-union of type II odontoid fracture.

Delayed union of type II odontoid fracture can present with similar symptoms. Displacement of the fragments can also determine delayed compression on the spinal cord with myelopathy symptoms.

Cervical CT-scan showing a transverse fracture line of the odontoid process below the transverse ligament. There was minimal fracture displacement with fragments osteoporosis and sclerotic bony margins (non-union).

Rigid external immobilization with cervical collar (Philadelphia) and systemic anabolic therapy with Teriparatide (20 μg/die) for 12 wk.

Painful non-union is common after conservative treatment of type II odontoid fractures in elderly patients. Treatment options involve delayed surgical stabilization and fusion or conservative treatment with analgesia and external rigid immobilization. Stability must be assessed with flexion/extension X-rays to prevent delayed cervical myelopathy.

Systemic Teriparatide therapy can be a valuable alternative approach to surgical fixation and fusion in symptomatic non-unions of the odontoid process. Teriparatide use for fracture healing enhancement is non Food and Drug Administration approved and must be considered “off label”.

Authors report the treatment of a relatively common disease (a type II odontoid fracture) with a widely used therapeutic approach in enhancing fracture healing (teriparatide), that has not been specifically reported as a therapeutic agent in this precise condition.

| 1. | Denaro V, Papalia R, Di Martino A, Denaro L, Maffulli N. The best surgical treatment for type II fractures of the dens is still controversial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:742-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ryan MD, Henderson JJ. The epidemiology of fractures and fracture-dislocations of the cervical spine. Injury. 1992;23:38-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Spivak JM, Weiss MA, Cotler JM, Call M. Cervical spine injuries in patients 65 and older. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:2302-2306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vaccaro AR, Kepler CK, Kopjar B, Chapman J, Shaffrey C, Arnold P, Gokaslan Z, Brodke D, France J, Dekutoski M. Functional and quality-of-life outcomes in geriatric patients with type-II dens fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:729-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ryan MD, Taylor TK. Odontoid fractures in the elderly. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:397-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hadley MN, Dickman CA, Browner CM, Sonntag VK. Acute axis fractures: a review of 229 cases. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:642-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Clark CR, White AA. Fractures of the dens. A multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1340-1348. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Apfelbaum RI, Lonser RR, Veres R, Casey A. Direct anterior screw fixation for recent and remote odontoid fractures. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:227-236. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jeanneret B, Magerl F. Primary posterior fusion C1/2 in odontoid fractures: indications, technique, and results of transarticular screw fixation. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5:464-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Harms J, Melcher RP. Posterior C1-C2 fusion with polyaxial screw and rod fixation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:2467-2471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1073] [Cited by in RCA: 1054] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Koivikko MP, Kiuru MJ, Koskinen SK, Myllynen P, Santavirta S, Kivisaari L. Factors associated with nonunion in conservatively-treated type-II fractures of the odontoid process. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:1146-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Crockard HA, Heilman AE, Stevens JM. Progressive myelopathy secondary to odontoid fractures: clinical, radiological, and surgical features. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:579-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Campbell EJ, Campbell GM, Hanley DA. The effect of parathyroid hormone and teriparatide on fracture healing. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:119-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Andreassen TT, Ejersted C, Oxlund H. Intermittent parathyroid hormone (1-34) treatment increases callus formation and mechanical strength of healing rat fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:960-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Andreassen TT, Fledelius C, Ejersted C, Oxlund H. Increases in callus formation and mechanical strength of healing fractures in old rats treated with parathyroid hormone. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:304-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mognetti B, Marino S, Barberis A, Martin AS, Bala Y, Di Carlo F, Boivin G, Barbos MP. Experimental stimulation of bone healing with teriparatide: histomorphometric and microhardness analysis in a mouse model of closed fracture. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;89:163-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Alkhiary YM, Gerstenfeld LC, Krall E, Westmore M, Sato M, Mitlak BH, Einhorn TA. Enhancement of experimental fracture-healing by systemic administration of recombinant human parathyroid hormone (PTH 1-34). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:731-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Roche B, Vanden-Bossche A, Malaval L, Normand M, Jannot M, Chaux R, Vico L, Lafage-Proust MH. Parathyroid hormone 1-84 targets bone vascular structure and perfusion in mice: impacts of its administration regimen and of ovariectomy. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1608-1618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Aspenberg P, Genant HK, Johansson T, Nino AJ, See K, Krohn K, García-Hernández PA, Recknor CP, Einhorn TA, Dalsky GP. Teriparatide for acceleration of fracture repair in humans: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 102 postmenopausal women with distal radial fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:404-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Peichl P, Holzer LA, Maier R, Holzer G. Parathyroid hormone 1-84 accelerates fracture-healing in pubic bones of elderly osteoporotic women. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:1583-1587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bukata SV, Puzas JE. Orthopedic uses of teriparatide. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2010;8:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rubery PT, Bukata SV. Teriparatide may accelerate healing in delayed unions of type III odontoid fractures: a report of 3 cases. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2010;23:151-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Elgafy H, Gonzalez-Reimers E, Ma DY S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL